Abstract

In complex materials observed electronic phases and transitions between them often involve coupling between many degrees of freedom whose entanglement convolutes understanding of the instigating mechanism. Metal-insulator transitions are one such problem where coupling to the structural, orbital, charge and magnetic order parameters frequently obscures the underlying physics. Here, we demonstrate a way to unravel this conundrum by heterostructuring a prototypical multi-ordered complex oxide NdNiO3 in ultra thin geometry, which preserves the metal-to-insulator transition and bulk-like magnetic order parameter, but entirely suppresses the symmetry lowering and long-range charge order parameter. These findings illustrate the utility of heterointerfaces as a powerful method for removing competing order parameters to gain greater insight into the nature of the transition, here revealing that the magnetic order generates the transition independently, leading to an exceptionally rare purely electronic metal-insulator transition with no symmetry change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the greatest challenges of condensed matter physics involves exposing the true underlying mechanisms giving rise to the observed anomalous properties, a situation greatly complicated by the coupling of various interactions, for example competing nematic, structural and spin transitions in iron pnictide1,2 or intertwined charge, magnetic and superconducting order parameters in underdoped high-Tc cuprates3,4. In strongly correlated electronic materials, the notion of complexity has been synonymous with multiple and often antagonistic ordered phases of intertwined charge, spin and orbital degrees of freedom3,4,5,6,7. True insight into the ground state of these materials thus necessitates the ability to selectively eliminate these degrees of freedom to reveal individual contributions.

As a classic case in question, the crossover of an electrically conducting state of a solid into a phase wherein the movement of carriers is prohibited is a prototypical example of such a problem. This metal-to-insulator transition (MIT) is frequently accompanied by emergent order parameters including structural modulation, magnetic, charge and orbital orderings etc., making it an arduous task to decipher the decisive interaction behind the transition8. Despite these complications, metal-insulator transitions have been controllably modified by external stimuli in an effort to disentangle the coupled order parameters to uncover the true progenitor9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Congruent to this effort, a deterministic control over the interfaces between layers with distinct or competing order parameters has further widened the traditional modalities that govern the global phase behavior of correlated electrons17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. The heterointerface approach naturally brings forward the important question of whether it is possible to selectively modulate a specific ordering to reveal the primary cause for the phase transition into a multi-ordered ground state. Unlike the previously mentioned efforts, where the system comes back to the original ground state when the external stimulus is removed, the present study undertook to suppress order parameters by the virtue of epitaxial stabilization, effectively freezing the system in an atypical state.

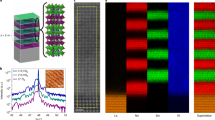

Specifically, a 15 unit cell thin film of rare-earth nickelate NdNiO3 (NNO) is utilized as a model system exhibiting a first-order MIT that in the bulk involves structural, charge and antiferromagnetic order parameters whose entanglement has obscured true understanding of the mechanism underpinning the transition, Fig. 1A,C 6,7,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38. Interestingly, recent work by Hepting and Wu et al. has shown that superlattices under compressive strain utilizing PrNiO3 and PrAlO3 can suppress the MI- and charge order (CO) transitions, while preserving the AFM transition, leading a rare metallic AFM state28,29. These considerations suggest some connection with the magneticly driven Slater transition, found experimentally for the first time recently39,40,41,42,43. However, several key differences between the nickelates and a pure Slater transition are evident, namely the first-order nature of the MIT and the large spectral weight transfer6,44. These factors indicate a Mott-like nature of the MIT, but the commensurate magnetic transition also rules out a true Mott MIT44,45,46. Our experiment, spanning x-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and resonant x-ray scattering (RXS), demonstrates that in the ultra thin limit for films the MIT persists with the same bulk-like E′- antiferromagnetic ordering and changes in electronic structure while the charge order parameter and accompanying structural transition, are completely removed at all temperatures. These findings imply the exceptional case of an isosymmetric and purely electronic metal-insulator transition, as seen in some Mott transitions15,47, driven by both strongly correlated electrons and magnetic ordering and is in sharp contrast to the present understanding of the physics of rare-earth nickelates34,35,36,37.

Electronic and Magnetic Configuration

Reduction of the degrees of freedom through heterostructuring presumably alters the electronic structure from it’s bulk-like state. Indeed, in nickelates, thin-film geometry and proximity to the interface has been shown to strongly alter the electronic structure of the constituent layers and, thus, requires investigation; numerous XAS reports detail the change of the electronic structure across the MIT showing a characteristic splitting of the Ni L3 edge below the MIT into two distinct peaks and a narrowing of the d-electron bandwidth in the insulating state6,7,25,32,48,49. These two distinct effects are the spectroscopic signatures of the stabilization of an insulating state in the nickelates. As seen in Fig. 2A, in the case of ultra thin films of NNO, the Ni L3 edge does indeed show a clear splitting below the MIT, with a line shape that clearly indicates the stabilization of the Ni3+ state6,25,32. Tracking the intensity in between the two peaks (inset of Fig. 2A) confirms a distinct spectroscopic change quantitatively very close to bulk-like behavior across the MIT49. Similarly, the O K-edge pre-peak reflects the band narrowing across the MIT, Fig. 2B; the sudden shift in bandwidth is commensurate with the onset of the insulating state at ~150 K, (Fig. 3A, solid lines)25. This prepeak arises due to hole doping of the O sites and is an important element in charge transfer insulators, with early work showing the importance for RNO50.The first-order nature of the transition is evident by the thermal hysteresis of the MIT6,7,25,28,34. Thus, both XAS and transport measurements affirm that the ultra thin structural motif does not generate any anomalous electronic structure effects across the MIT, making it an ideal candidate for investigation of the commensurate order parameters.

(A) XAS at the Ni L3-edge for the metallic and insulating states. Inset shows the intensity between the Ni3+ and multiplet peaks, highlighting the sudden narrowing of the peaks across the MIT. (B) XAS at the O K-edge for the same. Inset shows the change in the FWHM, arrows, of the O prepeak showing the bandwidth narrowing. All hatched lines are guides to the eye.

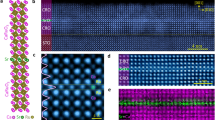

(A) Left axis: Temperature dependence DC transport for cooling (blue) and warming (cyan) cycles showing a strong hysteresis typical of the first-order MIT. Right Axis: Temperature dependence of the forbidden Bragg peak intensity corresponding to the magnetic order parameter. (B) Low and high temperature magnetic Bragg peak corresponding to E′-type anti-ferromagnetism. The inset shows the resonant energy scan at the Ni L3 and L2 at the peak at 20 K.

Spin ordering is a prevalent ingredient in Mott transitions8,51. In fact, Mott transitions feature local moments both above and below the MIT, as evidenced for these films in the supplementary information. In the nickelates, the magnetic ordering has received widespread attention due to the unusual stacking of ferromagnetic planes along the (1 1 1)pc (pc = pseudo-cubic) direction that are coupled antiferromagnetically (AFM) to one another in an up-up-down-down pattern, a non-collinear periodic behavior and a magnetic unit cell consisting of four structural unit cells, shown in Fig. 1C 52,53. Probing this anomalous, E′- AFM ordering in ultra-thin film geometry is quite challenging; Fig. 3A displays the results of the soft x-ray resonant scattering (RXS) at the (1/2 0 1/2)or (or = orthorhombic) reflection with the energy tuned to the Ni L3 edge (852 eV) below the MIT. This structurally forbidden Bragg reflection corresponds to a 4-fold unit cell repetition in the (1 1 1)pc direction. As seen in Fig. 3A, circles, the intensity of this reflection tracks very close with the MIT, suddenly rising above the background noise at around 140 K and steadily increasing until beginning to stabilize at low temperature. Both the periodicity and spectroscopic signature are in excellent agreement with previous studies on thick NdNiO3 films and bulk powders52,54. In short, these results show that the bulk E′-type AFM order parameter is preserved and conforms with the MIT despite bi-axial strain (~1.4%). With the expected electronic structure response (i.e. AFM order parameter and first-order MIT) the pinning of the lattice to the substrate does not cause any anomalous perturbation to the bulk-like magnetic and transport behavior of the nickelate film. In addition, for any bulk rare-earth nickelate, the insulating ground state is characterized by the presence of CO and the structural transition from the orthorhombic Pbnm symmetry of the metallic phase to monoclinic P21/n symmetry of the insulating phase6,7,35.

Probing Lattice Symmetry and Charge Ordering

First, we discuss the issue of lattice symmetry transformation, which is considered to be critical for the MIT. Heterostructuring naturally leads to a modulation of the film lattice due to the strong bonding with the substrate’s ions. When the film becomes thick enough the relaxation of elastic strain is inevitable and effectively decouples the film from the substrate55. In the ultra thin regime, however, the film is pinned to the substrate with no detectable relaxation and the heteroepitaxy infact controls the lattice degrees of freedom therein32,48.

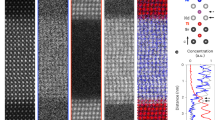

Pbnm (metal) and P21/n (insulator) space groups have the same Ni arrangement, however they are split into different Wycoff positions with the symmetry lowering. These inequivalent Ni sites carry a rock-salt pattern of charge disproportionation Ni3±δ (purely ionic picture) giving rise to the CO parameter. In recent years it has been found that, while hard RXS is a powerful tool for investigating charge ordering, careful analysis is required to avoid the misinterpretation of CO for small distortions of the oxygen octahedral network34,35,56. With this caution in mind, we investigated the (0 1 5)or and (1 0 5)or reflections, which are conventionally used to probe the lowering of the symmetry to monoclinic P21/n, Fig. 4A,B 34,35,56,57,58. The (105)or and (015)or peaks were chosen as they were shown to be quite sensitive to Ni CO in numerous previous studies34,35,36,37.

Figure 4A displays scans along the L reciprocal space vector (L-scan) at the (0 1 5)or and (1 0 5)or peaks. The (1 0 5)or peak is symmetry allowed for orthorhombic NNO, as a Bragg peak corresponds to the Nd sublattice, thus the film peak with Kiessig fringes is anticipated. As expected above the CO transition, this (105) reflection should have no Ni contribution until the charge ordering breaks the Pbnm symmetry in the low temperature insulating phase; the CO then leads to an additional contribution to the peak from Ni causing a sharp change in signal strength, especially when the x-rays are tuned to the resonant Ni K-edge (8.34 keV)35. Surprisingly, as the temperature is scanned across the MIT, no detectable change in the peak intensity is observed, Fig. 4A inset. With an intensity error of approximately 5%, this implies an upper limit on CO below our detection limit of 2δ = 0.073 ± 0.007e, insignificant compared to the 2δ = 0.45 ± 0.04e found by Staub et al.34. This result immediately implies that neither charge ordering nor the associated symmetry breaking occurs across the transition. Lending additional evidence, the (0 1 5)or peak, which is symmetry-forbidden for Pbnm, does not appear at any temperature, thus confirming the isosymmetric nature of the MIT34.

Furthermore, a key feature of resonant scattering is that the additional terms within the scattering factor are highly sensitive to the x-ray energy around an absorption edge59,60. Figure 4B shows the energy scan at the (1 0 5)or peak which further corroborates the above picture with higher sensitivity, confirming that no Ni resonance signal (i.e. symmetry lowering) is detected below the MIT. This is in stark contrast to all previous reports on both thick films and bulk where strong, temperature dependent resonance was shown to track with the MIT34,35,36,37. To further verify this finding, the allowed (2 2 0)or reflection was measured and shows the expected Ni resonance signal, confirming that the Ni contribution is certainly detectable in our experimental setup. These results confirm that across the MIT (i) no bond disproportionation of NiO6 occurs and the metallic phase Pbnm lattice symmetry is preserved35,36 and (ii) since no detectable Ni resonance is observed no charge ordering emerges in the insulating phase. These findings imply that the ultra thin films have stabilized a previously unknown nickelate ground state consisting of an insulating orthorhombic phase with AFM order. However, ultra thin films of the more strongly distorted EuNiO3 on NGO substrates displayed bulk-like CO, suggesting this anomalous state occupies only a narrow band of phase space61. Intriguingly, as observed here, the case of a phase transition without a structural symmetry change can only be first order and is exceptionally rare in complex materials, with the most prominent examples being analogous to the liquid-gas transformation51,62. For complex oxides, to our best knowledge, there are only two known cases of this type of MIT, i.e. Cr-doped V2O315 and the surface driven Ca1.9Sr0.1RuO447. It should be noted, experiments have also reported evidence of photoinduced MITs without resolved structural transitions63,64. Finally, these measurements are sensitive to long range ordering and do not rule out the possibility of a short-range charge ordered state on Ni or bond-centered ordering65,66.

Theoretical Presage

Driven by the heterointerface, CO removal and the stabilization of the unknown Mott phase within this class of materials is of great interest and yet has some precedent in past theoretical work38,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74. For example, two recent studies utilizing different theoretical methods by Lee et al.67,68 have proposed that the CO is slaved to the E′-magnetic ordering in the weak coupling limit and can indeed disappear under certain conditions; in particular, using Landau theory, the theory suggests that restricting the nickelates to the ultra-thin film regime may remove the CO. On the other hand, the predicted phase changes the Q-vector for the antiferromagnetic ordering, which is in variance with the experiment. Beyond this, Park et al. have demonstrated that within dynamical mean field theory (DMFT), despite the near Fermi-energy imbalance in the spectral weight between the two Ni sites, the total valence of Ni on both sites is practically identical, with the two different Ni sites instead hybridizing with O, leading to an S = 1 state on the larger octahedra (3d8) and an S = 0 state formed due to AFM coupling with the O holes (3d8)73,74. However, when the lattice symmetry is raised to Pbnm a metallic state with no MIT has emerged. More recently, Johnston et al.72 utilized Hartee-Fock methods to show the NiO6 octahedra form an alternating pattern of collapsed and expanded octahedra, giving a d8 + d8L2 state, where no CO on Ni occurs.

Finally, using LSDA + U calculations, Yamamoto et al.38 obtained results that are in the good agreement with our observations. Specifically, the calculated electronic and magnetic structure in orthorhombic NNO is found to be an insulating state with no Ni CO (as expected for equivalent Ni sites in Pbnm symmetry). In addition, the calculation shows that the magnetic space group is lowered to monoclinic due to different spin density polarizations around two O sites that preserve the equivalence of Ni sites in the Pbnm space group. Most importantly, this symmetry breaking state involving holes on oxygen and driven by the Hubbard U, opens an insulating gap, which agree well with the previous work44. At this point we can conjecture that while in the bulk structural symmetry is indeed lowered to P21/n, the epitaxial interface is able to preserve the orthorhombic structural symmetry of the metallic phase. The resulting ground state, observed experimentally, can be obtained within the LSDA + U framework, supporting the notion that the bulk-like MIT and magnetic order parameter can be attained with the charge and structural order parameters removed. In this work, we find the heterointerface acts as a powerful tool to effectively isolate the magnetic order parameter, which drives the bulk-like MIT independently.

Concluding Remarks

In conclusion, the reduction of the number of simultaneously competing order parameters commensurate with a phase transition from a metallic to an insulating state with both Mott and Slater characteristics has been achieved on a prototypical ultra thin film of NNO. The thin film heteroepitaxy prevents symmetry lowering from Pbnm to P21/n across the MIT, thus removing the bulk-like CO parameter. Despite this anomalous state, the MIT persists with no significant effect on the magnetic order parameter. The magnetic order parameter is identified as the culprit which drives the pure electronic MIT in the nickelates, highlighting the utility of this emerging method to sunder the competing order parameters. Our findings suggest that application of this method to eliminate specific order parameters to highly entangled or “hidden” orders found in cuprates, pnictides, heavy fermions and chalcogenides families may shed new light on their anomalous ground states2,75.

Methods

Epitaxially stabilized ultra thin (15 uc) films of NdNiO3 on (110)or oriented NdGaO3 substrates grown by pulsed laser deposition, various other techniques have confirmed the high quality of these films32. This orientation stabilizes the NNO films with the psuedo-cubic (pc) c-axis oriented in the growth direction. To elucidate the electronic structure, x-ray absorption spectroscopy was measured at the 4-ID-C beam line of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory. In order to investigate whether the bulk-like E′-type anti-ferromagnetic ordering occurs in these ultra thin films, systematic resonant soft x-ray scattering experiments were performed on the Ni L3 edge at the (1/2 0 1/2)or forbidden Bragg reflection at several temperatures traversing the MIT at the BL8 beam line of the Advanced Light due to the drastic enhancement of the magnetic scattering cross sections for transition metals’ L-edges59,60. Data was taken with a two-dimensional detector with the peak area integrated. In contrast to this, to probe the charge ordering in these systems higher order reflections, such as the (1 0 5)or, were measured with resonant hard x-ray scattering at the Ni K-edge at the 6-ID-B and 33-BM beam lines of the Advanced Photon Source due to the suitable wavelengths for diffraction from crystals34.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Meyers, D. et al. Pure electronic metal-insulator transition at the interface of complex oxides. Sci. Rep. 6, 27934; doi: 10.1038/srep27934 (2016).

References

R. M. Fernandes, A. V. Chubukov & J. Schmalian . What drives nematic order in iron-based superconductors? Nature Physics 10, 97 (2014).

D. C. Johnston . The puzzle of high temperature superconductivity in layered iron pnictides and chalcogenides. Advances in Physics 59, 803 (2010).

S. Sachdev . Colloquium: Order and quantum phase transitions in the cuprate superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys 75, 913 (2003).

N. P. Armitage, P. Fournier & R. L. Greene . Progress and perspectives on electron-doped cuprates. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 2421 (2010).

M. B. Salamon & M. Jaime . The physics of manganites: Structure and transport. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 583 (2001).

M. L. Medarde . Structural, magnetic and electronic properties of perovskites (R = rare earth). J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 9, 1679 (1997).

G. Catalan. Progress in perovskite nickelate research. Phase Transitions 81, 729 (2008).

M. Imada, A. Fujimori & Y. Tokura . Metal-insulator transitions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 70, 1039 (1998).

M. M. Qazilbash et al. Mott Transition in VO2 Revealed by Infrared Spectroscopy and Nano-Imaging. Science 318, 1750 (2007).

V. R. Morrison et al. A photoinduced metal-like phase of monoclinic VO2 revealed by ultrafast electron diffraction. Science 346, 445 (2013).

L. Stojchevska et al. Ultrafast Switching to a Stable Hidden Quantum State in an Electronic Crystal. Science 344, 177 (2014).

C. H. Ahn et al. Electric field effect in correlated oxide systems Nature 424, 1152 (1999).

J. Jeong et al. Suppression of Metal-Insulator Transition in VO2 by Electric Field-Induced Oxygen Vacancy Formation. Science 339, 1402 (2013).

A. T. Bollinger et al. Superconductor-insulator transition in La2−xSrxCuO4 at the pair quantum resistance. Nature 472, 1015 (2003).

P. Limelette et al. Universality and Critical Behavior at the Mott Transition. Science 302, 89 (2003).

H. Kuwahara, Y. Tomioka, A. Asamitsu, Y. Moritomo & Y. Tokura . A First-Order Phase Transition Induced by a Magnetic Field. Science 270, 961 (1995).

J. Chakhalian, J. W. Freeland, A. J. Millis, C. Panagopoulos & J. M. Rondinelli . Colloquium: Emergent properties in plane view: Strong correlations at oxide interfaces. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 1189 (2014).

J. Mannhart & D. G. Schlom. Oxide Interfaces? An Opportunity for Electronics. Science 327, 1607 (2010).

H. Y. Hwang et al. Emergent phenomena at oxide interfaces. Nature Materials 11, 103 (2012).

J. Chakhalian et al. Orbital Reconstruction and Covalent Bonding at an Oxide Interface. Science 318, 1114 (2007).

J. Chakhalian et al. Magnetism at the interface between ferromagnetic and superconducting oxides. Nature Physics 2, 244 (2006).

J. Chakhalian, A. J. Millis & J. Rondinelli . Whither the oxide interface. Nat. Mat. 11, 92–94 (2012).

S. Middey et al. Mott Electrons in an Artificial Graphenelike Crystal of Rare-Earth Nickelate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 056801 (2016).

Y. Cao et al. Engineered Mott ground state in LaTiO3+d/LaNiO3 heterostructure. Nature Communications 7, 10418 (2016).

J. Liu et al. Heterointerface engineered electronic and magnetic phases of NdNiO3 thin films. Nat. Comm. 4, 2714 (2013).

I. I. Mazin et al. Charge Ordering as Alternative to Jahn-Teller Distortion. Phys. Rev. Lett 98, 176406 (2007).

A. Frano et al. Orbital Control of Noncollinear Magnetic Order in Nickel Oxide Heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 106804 (2013).

M. Hepting et al. Tunable Charge and Spin Order in PrNiO3 Thin Films and Superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 227206 (2014).

M. Wu et al. Orbital reflectometry of PrNiO3/PrAlO3 superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 91, 195130 (2015).

Hauser et al. Correlation between stoichiometry, strain and metal-insulator transitions of NdNiO3 films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 092104 (2015).

E. Benckiser et al. Orbital reflectometry of oxide heterostructures. Nature Materials, 10, 189 (2011).

J. Liu et al. Strain-mediated metal-insulator transition in epitaxial ultra-thin films of NdNiO3 . Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 233110 (2010).

Y. Bodenthin et al. Magnetic and electronic properties of RniO3 (R = Pr, Nd, Eu, Ho and Y) perovskites studied by resonant soft x-ray magnetic powder diffraction. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 23, 036002 (2011).

U. Staub et al. Direct Observation of Charge Order in an Epitaxial NdNiO3 Film. Phys. Rev. B 88, 126402 (2002).

J. E. Lorenzo et al. Resonant x-ray scattering experiments on electronic orderings in NdNiO3 single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 71, 045128 (2005).

V. Scagnoli et al. Charge disproportionation and search for orbital ordering in NdNiO3 by use of resonant x-ray diffraction. Phys. Rev. B 72, 155111 (2005).

V. Scagnoli et al. Charge disproportionation observed by resonant X-ray scattering at the metal-insulator transition in NdNiO3 . Jour. Mag. Mag. Mat. 272–276, 420–421 (2004).

S. Yamamoto & T. Fujiwara . Charge and Spin Order in RniO3 (R = Nd, Y) by LSDA + U Method. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 71, 1226- 1229 (2002).

J. C. Slater . Magnetic Effects and the Hartree-Fock Equation. Phys. Rev. 82, 538 (1951).

D. Mandrus et al. Continuous metal-insulator transition in the pyrochlore Cd2Os2O7 . Phys. Rev. B 63, 195104 (2001).

W. J. Padilla, D. Mandrus & D. N. Basov . Searching for the Slater transition in the pyrochlore Cd2Os2O7 with infrared spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 66, 035120 (2002).

S. Zhao et al. Magnetic transition, long-range order and moment fluctuations in the pyrochlore iridate Eu2Ir2O7 . Phys. Rev. B 83, 180402(R) (2011).

S. Calder et al. Magnetically Driven Metal-Insulator Transition in NaOsO3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 257209 (2012).

M. K. Stewart, J. Liu, M. Kareev, J, Chakhalian & D. N. Basov . Mott Physics near the Insulator-To-Metal Transition in NdNiO3 . Phys. Rev. Lett 107, 176401 (2011).

M. K. Stewart et al. Optical study of strained ultra thin films of strongly correlated LaNiO3 . Phys. Rev. B 83, 075125 (2011).

D. G. Ouellette et al. Optical conductivity of LaNiO3: Coherent transport and correlation driven mass enhancement. Phys. Rev. B 82, 165112 (2010).

R. G. Moore et al. A Surface-Tailored, Purely Electronic, Mott Metal-to-Insulator Transition. Science 318, 615 (2007).

D. Meyers et al. Strain-modulated Mott transition in EuNiO3 ultrathin films. Phys. Rev. B 88, 075116 (2013).

J. W. Freeland, M. v. Veenendaal & J. Chakhalian . Evolution of electronic structure across the rare-earth RniO3 series. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 10, 1016 (2015).

T. Mizokawa et al. Electronic structure of PrNiO3 studied by photoemission and x-ray-absorption spectroscopy: Band gap and orbital ordering. Phys. Rev. B 52, 13865–13873 (1995).

D. I. Khomskii . Basic aspects of the quantum theory of solids, Ch. 2, 6–30 (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

V. Scagnoli et al. Role of magnetic and orbital ordering at the metal-insulator transition in NdNiO3 . Phys. Rev. B 73, 100409(R) (2006).

V. Scagnoli et al. Induced noncollinear magnetic order of Nd3+ in NdNiO3 observed by resonant soft x-ray diffraction. Phys. Rev. B 77, 115138 (2008).

J. L. Garcia-Munoz, J. Rodriquez-Carvajal & P. Lacorre . Neutron-diffraction study of the magnetic ordering in the insulating regime of the perovskites RniO3 (R = Pr and Nd). Phys. Rev. B 50, 2 (1994).

A. R. Kaul, O. Y. Gorbenko & A. A. Kamenev . The role of heteroepitaxy in the development of new thin-film oxide-based functional materials. Russ. Chem. Rev. 73, 861 (2004).

J. Garcia, M. C. Sanchez, G. Subias & J. Blasco . High resolution x-ray absorption near edge structure at the Mn K edge of manganites. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 13, 3229–3241 (2001).

M. H. Upton et al. Novel electronic behavior driving NdNiO3 metal-insulator transition. Phys. Rev. Lett 115, 036401 (2014).

Y. Lu et al. Quantitative determination of bond order and lattice distortions in nickel oxide heterostructures by resonant x-ray scattering. Phys. Rev. B 93, 165121 (2016).

J. Fink, E. Schierle, E. Weschke & J. Geck . Resonant elastic soft x-ray scattering. Rep. Prog. Phys. 76, 056502 (2013).

J.-L. Hodeau et al. Resonant Diffraction. Chem. Rev. 101, 1843–1867 (2001).

D. Meyers et al. Charge order and antiheromagnetism in epitaxial ultra thin films of EuNiO3 . Phys. Rev. B 92, 235126 (2015).

H. Shimahara . Phase Transition without Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking between Hard and Soft Solid States. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 74, 823 (2005).

Z. Tao et al. Decoupling of Structural and Electronic Phase Transitions in VO2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 166406 (2012).

S. H. Dietze et al. X-ray-induced persistent photoconductivity in vanadium dioxide. Phys. Rev. B 90, 165109 (2014).

J. L. García-Muñoz, J. Rodrígues-Carvajal, P. Lacorre & J. B. Torrance . Neutron-diffraction study of RniO3 (R = La, Pr, Nd, Sm): Electronically induced structural changes across the metal-insulator transition. Phys. Rev. B 46, 4414 (1992).

C. Piamonteze et al. Short-range charge order in RniO3 perovskites (R = Pr, Nd, Eu, Y) probed by x-ray-absorption spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 71, 012104 (2005).

S. B. Lee, R. Chen & L. Balents . Landau Theory of Charge and Spin Ordering in the Nickelates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 016495 (2011).

S. B. Lee, R. Chen & L. Balents . Metal-insulator transition in a two-band model for the perovskite nickelates. Phys. Rev. B 84, 165119 (2011).

S. Prosandeev, L. Bellaiche & J. Íñiguez . Ab initio study of the factors affecting the ground state of rare-earth nickelates. Phys. Rev. B 85, 214431 (2012).

T. Mizokawa, D. I. Khomskii & G. A. Sawatzky . Spin and charge ordering in self-doped Mott insulators. Phys. Rev. B 61, 17 (2000).

B. Lau & A. J. Millis . Theory of the Magnetic and Metal-Insulator Transitions in RniO3 Bulk and Layered Structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 126404 (2013).

S. Johnston et al. Charge Disproportionation without Charge Transfer in the Rare-Earth-Element Nickelates as a Possible Mechanism for the Metal-Insulator Transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 106404 (2014).

H. Park, A. J. Millis & C. A. Marianetti . Site-Selective Mott Transition in Rare-Earth-Element Nickelates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 156402 (2012).

H. Park, A. J. Millis & C. A. Marianetti . Total energy calculations using DFT + DMFT: Computing the pressure phase diagram of the rare earth nickelates. Phys. Rev. B 89, 245133 (2014).

B. Keimer, S. A. Kivelson, M. R. Norman, S. Uchida & J. Zaanen . From quantum matter to high-temperature superconductivity in copper oxides. Nature 518, 179 (2015).

Acknowledgements

J. C. was primarily supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation EPiQS Initiative through grant number GBMF4534. S. M. and D. M. were supported by the Department of Energy grant DE-SC0012375 for synchrotron work at the Advanced Photon Source. M. K. was supported by the DOD-ARO under grant number 0402–17291 for material synthesis. J. L. is sponsored by the Science Alliance Joint Directed Research and Development Program at the University of Tennessee. Work at the Advanced Photon Source is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science under grant No. DEAC02-06CH11357. Work at the Advanced Light Source is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. We acknowledge insightful discussions with D. Khosmskii, A. J. Millis, D. D. Sarma, P. Mahadevan, G. Kotlier and W. Plummer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.M., J.L., S.M., J.W.F. and J.C. wrote the manuscript. J.L., J.W.F., J.M.Z., Y.-D.C., J.W.K. and P.J.R. gathered the data. D.M., J.L., S.M. and M.K. grew the samples. J.W.K. and J.M.Z. performed STEM.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Meyers, D., Liu, J., Freeland, J. et al. Pure electronic metal-insulator transition at the interface of complex oxides. Sci Rep 6, 27934 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27934

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27934

This article is cited by

-

Quantifying the role of the lattice in metal–insulator phase transitions

Communications Physics (2022)

-

Electric-field-driven octahedral rotation in perovskite

npj Quantum Materials (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.