Abstract

Oxygen and carbon isotope ratios in planktonic foraminifera Globigerina bulloides collected from tow samples along a transect from the equatorial Indian ocean to the Southern Ocean (45°E and 80°E and 10°N to 53°S) were analysed and compared with the equilibrium δ18O and δ13C values of calcite calculated using the temperature and isotopic composition of the water column. The results agree within ~0.25‰ for the region between 10°N and 40°S and 75–200 m water depth which is considered to be the habitat of Globigerina bulloides. Further south (from 40°S to 55°S), however, the measured δ18O and δ13C values are higher than the expected values by ~2‰ and ~1‰ respectively. These enrichments can be attributed to either a ‘vital effect’ or a higher calcification rate. An interesting pattern of increase in the δ13C(DIC) value of the surface water with latitude is observed between 35°S and~ 60°S, with a peak at~ 42°S. This can be caused by increased organic matter production and associated removal. A simple model accounting for the increase in the δ13C(DIC) values is proposed which fits well with the observed chlorophyll abundance as a function of latitude.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Isotopic compositions of planktonic foraminifera are commonly used in the reconstruction of past oceanographic conditions but their reliability as environmental index depends on assumption of equilibrium condition at the time of growth and absence of subsequent alteration. Investigations on tow samples1,2,3,4 and samples from the sediment trap5,6,7,8 established a link between the geographical position and depth range of several planktonic species. Validation of the isotopic composition of Globigerina bulloides as a paleoclimate proxy was demonstrated by comparison of results of foraminiferal shell samples recovered by net from the water column and that from sediment core top samples. This comparison assumes that core top samples represents a time after the last glacial period when the oceanic environment remained relatively warm and stable and did not suffer any major changes9. It is known that G. bulloides is sensitive to oceanographic change from the results of its increased abundance due to changes in the monsoonal activity during the Holocene10. The G. bulloides proxy has been calibrated using modern sea-floor samples11 and sediment trap time series12, and has been tested over a range of timescales10. To generate long time series of oceanographic conditions from the geochemical analysis of fauna it is important to know how well the planktonic foraminifers preserve the signature of water properties.

The planktonic foraminifera species are mostly confined to the photic zone but the exact depth habitat inside that zone depends on their temperature and salinity preferences. Expected isotopic composition of a species can only be calculated if we know their depth habitat. Based on observations of the tow and core top samples the optimum growth preferences of G. bulloides species are at a temperature of 13.4 °C and a salinity of 34.8PSU13. In the Southern Ocean (SO) these values correspond to a depth of 50–100 m. This depth range is also commonly associated with the region of high chlorophyll and organic productivity14,15. However, even though the G. bulloides inhabits mainly the mixed layer2,14,16,17, their presence has been recorded up to about 200 m. Studies from the Mediterranean region18,19,20 showed that G. bulloides occurs over a large range of depth from 20 to 200 m in spring. Furthermore, there are recent suggestions that its calcification continues to depths even greater than 200 m21 and the test size varies according to the depth17. G. bulloides secretes its shell by adding new chambers intermittently. Each new chamber has a thicker wall and a larger volume than the preceding one16. While forming the new chamber, a new layer is also secreted over the outer surface of the previous chambers and this can take place even within a few hours13. While primary calcification, i.e., the formation of fresh chambers, seems to occur mainly in the upper water column, some individuals secrete calcite while descending along the water column (also known as secondary or gametogenic calcification)22,23. Correspondingly, two distinct calcite compositions have been observed in response to two kinds of fractionating mechanisms: (1) reservoir fractionation24 and (2) active regulation of the internal calcite saturation under biological control25. After its death, probably within a few weeks of its birth16,26, the organism sinks to the sea floor. At equilibrium, the oxygen isotopic ratio of its carbonate shell should depend on the oxygen isotopic composition and temperature of the ambient sea water when it is alive. The carbon isotopic composition, on the other hand, depends on the composition of the dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and temperature. These parameters change with depth and therefore knowledge of the depth habitat is essential for calculation of the equilibrium isotopic compositions of the calcite and compare them with the measured isotopic ratios in either the tow or core top samples.

In this work, we aim to study the effect of changes in the water mass properties (temperature and salinity) with depth and latitudinal position on the incorporation of 18O and 13C into the foraminiferal test of G. bulloides. We also compare results of tow samples with the published data of core top samples collected earlier in the same region. In addition, the observed latitudinal distribution of δ13C(DIC) in surface water of the Southern Ocean obtained by our earlier study27 is sought to be explained by a simple model of production and export of organic matter.

Diverse zones of water in the Southern Ocean

Based on the presence of different water masses in the Southern Ocean, characterized by temperature and salinity changes with latitude, the region has been divided in to several zones described as follows. The Tropical Indian Ocean (TIO) is characterized by a confluence of diverse water masses, each with distinct physical characteristics, nutrient conditions, and production rates extending from 20°N to 20°S. The Subtropical zone (STZ)28 is characterized by warm, oligotrophic waters, it lies between 20°S to 35°S, the SST is more than 20 °C and the Sea Surface Salinity (SSS) varies between 35–35.5. The Transition zone (TZ) is characterized by meridional gradients in all biogeochemical properties, it lies between 35°S to 40°S, where the SST varies between 15–20 °C and the SSS varies between 35–35.5. Next is the Sub-Antarctic Frontal zone (SAFZ) which is characterized by the presence of Sub-Antarctic Front (SAF) spanning 40°S to 45°S, where the temperature varies between 6–15 °C and the SSS varies between 33.85–35. Next is the Polar frontal zone (PFZ) spanning 45°S to 50°S where SST varies between 4–9 °C and the SSS is less than 33.85. Finally, the Antarctic zone (AAZ) is characterized as a High-Nutrient Low-Chlorophyll (HNLC) region and is located beyond 50°S where the SST is less than 4 °C and SSS is less than 33.8 . The biogeochemical characteristics of these zones are given in detail elsewhere27,28,29.

Frontal System Variability in the Indian Sector of the Southern Ocean

The frontal structure over the Indian Sector of the Southern Ocean which marks the transition between water masses has its own characteristic temperature and salinity as seen from an analysis of CTD and XCTD data. The fronts described in the present study are (1) Subtropical front (2) Sub-Antarctic front and (3) Polar front. The Subtropical front (STF) extends from 40 to 42°S30,31 where the SST drops from 22 to 11 °C and sea surface salinity is between 35.5–34.05 . Sub-Antarctic front (SAF) is identified between 45°30’S and 46°30’S and is characterised by a drop in SST from 11 to 6 °C and a salinity drop from 34 to 33.85. Polar front lies between 50°30’S and 56°30’S, and the SST drops from 5 to 2 °C and the SSS varies between 33.8–33.9. The frontal structures vary along the longitude as described previously by Anilkumar et al.,(2015)32 Belkin and Gordon (1996)30 and Kostianoy et al., (2004)33.

The water and tow samples were collected from various locations across these zones and analysed for isotopes as described below.

Results and Discussions

δ18O and δ13C values in G. bulloides

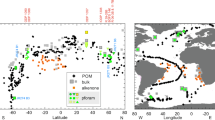

Isotopic analyses of foraminifera specimens obtained from sediment samples collected on board ORV Sagar Kanya from the TIO and Southern Ocean region during her 199th and 200th cruises respectively have been reported earlier34. We have now measured the δ13C and δ18O values of contemporary living specimens of foraminifera collected by towing from the same region. These data are shown in Fig. 1(a,b) and are given in Table 1 along with the results of sediment core top samples obtained from Khare and Chaturvedi (2012). In summary, considering the whole Southern Ocean (starting from the tropical region to the Antarctic zone around 60 oS), the δ13C values display wide scatter, from −2.0 to −0.5‰, up to about 40 oS. Further south, the values are mostly high and lie within a narrow range of −0.3 to +0.7‰. In contrast, the δ18O values increase systematically from the tropical zone to the Antarctic zone from a low value of −2.0 to a high value +3.0‰.

(a)Latitudinal variability of δ13C values of Globigerina bulloides filled square represents present study, hollow triangle represents data obtained by Khare and Chaturvedi, (2012) (b) δ18O values of Globigerina bulloides;filled circles represent values of tow samples (present study), hollow diamonds represent values of sediment top samples (from Khare and Chaturvedi, 2012) (c) δ18O values of surface water samples represented by filled diamonds, square and triangle for 2011, 2012 and 2013 respectively (d) δ13C(DIC) values represented by hollow diamonds and square for 2012 and 2013 respectively. The thick grey line represents the chlorophyll-a concentration in mg/m3(zonal mean using data from-MODIS Aqua). Note the similarity of the profiles of changes of δ13C(DIC) (from 30 oS to 60 oS) and that of the chlorophyll-a concentration suggesting connection of isotopic enrichment with organic matter production.

δ18O and δ13C values of surface water

The latitudinal distribution of δ18O values of surface sea water is shown in Fig. 1(c) and are given in Table 2 as a summary of the overall picture, the values generally increase from a low tropical ocean value of −0.2 to about 1.0‰ at 42 oS. There is a sharp drop to −0.6 ± 0.2‰ even as one moves by a few degrees south.

The mean δ13C(DIC) values for the surface water samples taken from Prasanna et al., (2015)27 for the years 2012 and 2013, corresponding to the different biogeochemical zones discussed above, are shown in Fig. 1(d). Also plotted in this figure is the average chlorophyll-a concentration (in mg/m3) obtained from satellite measurement (during Austral summer) across this latitudinal belt. There is large inter-annual variability of mean δ13C(DIC) for the years 2012 and 2013. The mean value for the TIO and STZ (20°N to 35°S) is 0.81 ± 0.14‰. An overall enrichment of 0.29‰ was noted in TZ with mean value of 1.21 ± 0.16‰. SAFZ and PFZ show a large enrichment of ~1‰ with mean values of 1.54 ± 0.08‰ and 1.51 ± 0.02‰ respectively. Further south, AAZ showed a small extent of depletion compared to the peak zones with a mean value of 1.34 ± 0.1‰ (Table 1).

Predicted δ18O and δ13C values of G.bulloides

It is well known that the δ18O value of the G. bulloides shell depends on the δ18O value and temperature of the ambient water at the time of calcification23,35,36. Depth variation in the δ18O values of water and its temperature at several stations across the Southern Ocean have been reported before37. The seasonal variability of Mixed Layer Depth (MLD) across different zones and its implication on foraminiferal flux is discussed in the supplementary material. These values can be used in calculating the oxygen isotopic composition of carbonate precipitated under equilibrium condition at various depths in the Southern Ocean. For this, we use the following relationship proposed for G. bulloides38:

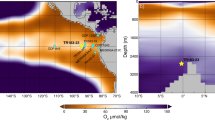

Expected δ18OShell value at a given depth is calculated first by plugging in the δ18Owater value and temperature for that depth. By repeating this procedure over the latitude range 10°N to 60°S we construct the depth contours of expected isotopic values shown in Fig. 2. Similar exercise is done for δ13C values using the temperature dependent fractionation for 13C between bicarbonate and carbonate and gaseous CO239:

Expected δ13Cshell values (for depths up-to 50 m) are calculated by plugging the δ13C values of surface water and temperature for that depth. For depths 50–1000 m, the δ13C(DIC) values and temperature of the water column were adapted from WOCEI9N and WOCEI8S data40 (http://www-pord.ucsd.edu/whp_atlas/indian_index.html). Using these inputs, depth contours of δ13C(DIC) values are generated and shown in Fig. 3.

δ13C(DIC) values in the surface waters as a function of latitude (Fig. 1d) show good correlation with the Chl-a concentration (r2 = 0.64). This is quite interesting since the two parameters refer to averaging over widely different time periods. The δ13C(DIC) is probably the steady state value of the local sea water representing many years (residence time) whereas the chlorophyll-a concentration refers to a snapshot picture obtained by the passing satellite. The enrichment of 13C/12C ratio with latitude, in particular, agrees well with the increase in photosynthetic activity. Similarly, the decreases at higher latitudes beyond 55 oS are found to be similar. We think that the correlated change in δ13C(DIC) and chlorophyll-a concentration with latitude can be explained by a simple mechanism. The Southern Ocean (SO) is characterised by high productivity and in places the phytoplankton density can yield as much as 1 gC/m2/day. Over about 100 day season, that yields 100 gC/m2/year (http://public.wsu.edu/~dybdahl/lec10.html). It is well known that production of organic matter preferentially uses the lighter carbon (12C) and leaves behind the heavier (13C) in sea water. For example, available data of ocean organic matter around 50 oS indicate a δ13C(POM) value of~ −25‰41,42. Therefore, a substantial increase in organic matter production (as evidenced by chlorophyll concentration increase across the latitudinal belt of 35 to 45 oS) would imply corresponding increment in the δ13C(DIC) values by the logic of mass balance. Thereafter, as the production decreases further south, the δ13C(DIC) values also drop but not as much as the northern flank of the peak zone. This qualitative expectation is modelled below using a simple isotopic mass balance formulation. The near-Gaussian type increase and decrease of chlorophyll concentration is indicative of phytoplankton production which in turn is related to supply of nutrients and availability of light for photosynthesis. The macro-nutrients are abundant in the SO due to yearly upwelling caused by formation and melting of sea ice. When ice forms the salt is rejected which increases the salinity of the sea water around the sea ice, causing it to become denser than surrounding water. The cold and salty brine sinks and is replaced by deeper water which is warmer and less dense and has high concentration of nutrients. This causes the ocean to overturn. This process of brine rejection causes the exchange between surface and deep water that keeps the surface of the SO supplied with nutrients. The nutrient supply is also controlled to a large extent by ocean currents (Antarctic Bottom Water circulation). The sea ice formation is higher as one moves further south and that induces more productivity (due to more brine rejection) and may partially explain the higher δ13C(DIC) values in the southern flank of the Gaussian type variation (Fig. 1d). The supply of micro-nutrient (like iron) also has an important role to play in the overall pattern of productivity.

Box Model of δ13C(DIC)

We use a box model to simulate the δ13C(DIC) values for the productive regions in the Southern Ocean (Fig. 4). The model accounts for the δ13C(DIC) values in a given location based on the production rate of organic carbon(Po), total organic carbon [OM] and the removal rate of organic carbon assumed to be equal to -λ*[OM]. In the surface ocean, phytoplankton takes up inorganic carbon (DIC) to produce organic carbon via photosynthesis. As mentioned before, this process discriminates against the heavy isotope; as a result, surface DIC becomes enriched in13C43. The primary organic matter, thus produced, is converted to Dissolved Organic Matter (DOM) and Particulate Organic Matter (POM) and part of these are consumed by zooplankton. However, this process would stop if there is no fresh supply of nutrients. There are multiple processes by which the organic matter decomposes and supplies back the nutrients for the production to continue44,45. It is seen that, of the organic matter generated by primary production, a major part is recycled, and only about 15 to 25% is exported below46. For the sake of simplicity we assume a steady state food web model47 where the export flux out of the box is proportional to the total organic matter (-λ*[OM]) in the box. It is easy to see that depending on the rate of production (Po) and the value of λ a stationary state is obtained after certain time when the amount of [OM] in the box and the δ13C(DIC) remain constant with time. Under this condition, the equation which governs the process of organic biomass (expressed as carbon) generation is:

Where [OM] is the total organic carbon biomass (DOM + POM), Po is the production rate of organic carbon, λ*[OM] is the rate of organic carbon removal. The organic carbon biomass thus calculated is used to calculate the δ13C (DIC) using the mass balance equation (t and 0 refer to the state at time ‘t’ and ‘0’ respectively) given below:

For the purpose of calculation, the DOM value is taken from Tremblay et al.48. The POM is calculated from the concentration data of Chl-a and the ratio of POM/Chl-a from 2012 measurements given by Soares et al.42. The DOM concentration is assumed to follow the Chl-a distribution normalized to a value of 51.1 μmole/kg corresponding to a Chl-a concentration of 0.54 mg/m3 at 3 oN. The DIC concentration is taken to be 2100 μmole/kg49, the typical observed value for the surface Southern Ocean. Using these inputs (Table 3) the predicted δ13C(DIC) values as a function of time are calculated (Table 3) and plotted in Fig. 5 for selected latitude bands. It is seen that for these productive bands the time to achieve the steady state value is about ~5,000 days and the predictions match the measured surface values quite well except in certain locations (between 45 oS and 60 oS). It is possible that in these locations the organic matter production has been estimated wrongly due to incorrect assumption about the Chl-a concentration. For example, this could be due to the inability of the satellite sensors to detect frequently occurring subsurface chlorophyll patches50. For a shortfall of 10 mg/m3 in the organic carbon the δ13C(DIC) changes by about 0.15‰. The prediction can be improved by simultaneous measurement of POM, DOM and DIC in the same location.

Comparison of δ13C and δ18O of G. bulloides

Tow and sediment core top samples

δ13C and δ18O values of both tow samples and sediment core top samples from Khare and Chaturvedi (2012) have been plotted in Fig. (1a,b) respectively. There are six locations where tow samples can be compared with the nearest sediment core top samples. Tow results from 53°S match with that of sediment coretop sample at 55°S within 0.02‰ for δ13C and 1‰ for δ18O. At 50°S δ13C value matches within 0.5‰ whereas δ18O value matches within 0.1‰. At three different stations at 43°S, δ13C values match within 0.3‰ whereas δ18O values match within 0.2‰. At 10°27′N the sample was collected near a coastal station. Here the δ13C value is higher by 0.58‰ due to possible riverine input. In contrast, the nearest location of sediment core top is at 9°24′N which has a value of −1.4‰. However, in the same sample the δ18O values match within 0.1‰ since the sea water represents a very large reservoir and is less affected by river input. The close agreement of tow samples with core top samples is quite interesting since the time interval covered by a typical core top sample is on a different scale (of the order of 1000 years) compared to the contemporary tow samples (less than a year). It shows that in these locations oceanographic conditions have not changed significantly during this time scale and the core top samples have not suffered major alterations since then.

Comparison of calculated δ-values with observations

The measured δ18O and δ13C values of foraminifera are compared with the δ18O and δ13C values expected at different depths across the latitude. As shown in Figs 2 and 3, the δ18O and δ13C values of foraminifera in the region between 10°N and 40°S agree within ~0.25‰ with the expected δ18O and δ13C values at ~75–200 m. Further southward from 40°S to 55°S, the measured δ18O values are higher than the expected δ18O values by ~2‰ at surface while the measured δ13C values of foraminifers are higher by ~1‰ than the expected δ13C values at surface (see Figs 2 and 3). It is of interest to note that the 18O difference is nearly twice that of the 13C difference. This may mean that the cause of the disequilibrium south of 40 oS should be due to a process of mass dependent kinetic fractionation.

There are number of possible reasons which together or singly can account for the mismatch beyond 40°S. We list them below and discuss their implications.

Deeper depth habitat than the one assumed

Planktic foraminifera G. bulloides inhabits the water above the thermocline at around 75 to 100 m51,52. The thermocline in the Indian sector of Southern Ocean is known to vary within the range of 75−150 m53. It is possible that at higher latitudes the calcite crust of G. bulloides forms at a deeper level especially after its death en-route to the sea bottom21. This would mean formation of calcite at temperatures lower than the surface resulting in higher δ18O values (Eq. 1). This is normally seen in deeper dwelling foraminiferal species such as G. truncatulinoides and G. inflata but this process is not known to be common for G. bulloides.

Partial dissolution

A second possible reason for enrichment in 18O/16O observed in samples of foraminifera beyond 40°S is partial dissolution. Previous studies suggested that partial dissolution shifts bulk δ18O and δ13C values towards the gametogenic calcite54,55. Ontogenic calcites dissolve faster in the process of partial dissolution compared to gametogenic calcite56,57. Since the addition of gametogenic calcite occurs in deeper water where the temperatures are colder one can have higher δ18O and δ13C values55,58. The enrichment in 18O can be attributed to relatively larger amount of gametogenic calcite formed at lower temperatures. In such case the lower enrichment in13C can be attributed to a “vital effect”59 associated with the gametogenic process

Non-equilibrium calcification

Third probable reason for the deviation (Fig. 4) from the expected δ18O and δ13C values of G. bulloides may be the presence of an unknown disequilibrium effect. One possible disequilibrium effect could be slower rate of reactions in various steps of CO2 hydration and hydroxylation leading to enhanced uptake of 13C and18O isotopes. Remote sensing (MODIS-AQUA) observations show high primary production in the Southern Ocean. As discussed above (Fig. 1d), with high productivity the ambient δ13C(DIC) values are higher60.13C enriched water due to high productivity along with a possible higher calcification rate can thus account for the observed disequilibrium59.

Oceanic Suess Effect

Atmospheric air CO2 has depleted δ13C composition since the industrial revolution due to the burning of fossil fuels61. Of all the emitted CO2 into atmosphere the nearly half of the CO2 is taken up by the ocean. Previous studies regarding change in δ13C of the surface ocean reported that the carbon isotopic composition of the oceans have become lighter through time due to the uptake of atmospheric CO260,62,63. In our samples the productivity signal masks this decrease in δ13C(DIC) in the surface waters. However, in 50 and 75 m there is clear decrease as reflected in the profile of δ13C(DIC) with latitude (Fig. 3). However, the Suess effect cannot explain the observed discrepancy since the calculations were done using the observed profiles which contain the changes due to the Suess effect.

Genetic Variability

Fifth probable reason for the deviation (Fig. 4) from the expected δ18O and δ13C values of G. bulloides may be due to genetic diversity64,65. The morpho-species diversity of G. bulloides is is known to increase in the sub-tropics and decrease steeply towards the poles. Studies of the SSU rRNA gene have identified high diversity in G. bulloides and they have been classified into two major groups namely Type I and Type II. Type I is predominantly found in warm tropical waters of Indo pacific and Atlantic oceans. Type II is found in cooler waters in the sub-polar and transitional zones of Antarctic. The genetic variability in G. bulloides could be one of the reasons for the observed disequilibrium.

It is clear that there are several possible reasons for the above mentioned disequilibrium. However, the nature of the discrepancy suggests that the biological effect (vital effect or genetic variability or gametogenic process) played a major role.

Conclusions

Globigerina bulloides retrieved from tow samples from various locations across the Southern Ocean between 10°N−60 oS were analysed for δ18O and δ13C values. The measured δ18O values, along with the earlier published values of sediment core top samples, are in good agreement with the values expected at equilibrium in the depth range of ~75–200 m upto 40°S latitude. Beyond 40°S, the δ18O values of the foraminifera show a deviation from prediction. Similarly, the δ13C values of the foraminifera agree with the expected equilibrium values based on ambient water δ13C(DIC) values upto 40°S, but further south, a deviation is observed.

Based on the similarities between the estimated and measured δ18O values, we conclude that the calcification depth of G. bulloides is confined to a depth of ~75–200 m till 40°S latitude. This is consistent with earlier studies. However, further south (>40 oS) an unknown disequilibrium process sets in which is responsible for a large offset between the observed and the predicted equilibrium values. Unless appropriate corrections can be made for this deviation, the G. bulloides data obtained from sediment cores cannot be considered as a reliable paleo-climatic proxy in the >40 oS region of the Southern Ocean. We suspect that this deviation may be due to genetic effect on the calcification but more work is needed to confirm this.

The pattern of enrichment in the 13C values of sea water with latitude (up to about 43°S) which is observed in the surface seawater matches well with the variation in the chlorophyll concentration obtained by satellite observations. This type of correlated distribution (Fig. 1d) can be explained by a simple box model of isotopic mass balance where the increased organic carbon production (having depleted 13C) enriches the ambient water. The model also shows that a steady state of the carbon isotope ratio of water can be achieved in a relatively short time of ~5000 days. Beyond 50 oS, the pattern changes and one sees lower δ13C(DIC) values. The overall pattern is controlled by the nutrient supply by ocean currents (Antarctic Bottom Water) and upwelling (by brine rejection process) and availability of light.

Methods

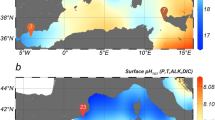

Multiple opening closing net and environmental sampling system (MOCNESS)66 was employed for sampling live foraminifera from the water column during December 2011–February 2012 on board ORV SagarNidhi (Fig. 6). The MOCNESS was configured with 200 μm nets and a 50 × 50 cm2 sample area designed to catch the foraminifera while towing the net 1000 m below the surface. Samples were collected from six stations over the latitudinal range of 10°N to 53°S and the longitudinal range of 75°E to 57°E as (see Table 1). The locations were dictated by previous sediment core samples. The locations of sampling have a high sedimentation rates and important sedimentary sequences. The MOCNESS stations are therefore appropriately located in areas of interest for microfossil calibration. Sampling locations were chosen to cover all the regions of biogeochemical interest described before. Water samples for isotopic measurement of DIC were collected from CTD/Rosette cast (just prior to MOCNESS deployment) in a glass amber bottle capped with butyl rubber septa and crimped with aluminium caps. 10 μl of saturated HgCl2 solution was added to the water samples to arrest post sampling biological activity during the long storage. For oxygen isotope analysis, surface water samples were collected separately.

The symbols are as follows: tow samples: red filled circles; filled circle and filled square: water samples. Surface sediment samples collected and studied by Khare and Chaturvedi (2012): Hollow circle. Map plotted using licensed Arc GIS 10 (http://www.esri.com/software/arcgis/arcgis-for-desktop).

Oxygen and Carbon isotope ratio analysis

In order to minimize possible size-related differences, δ18O analyses were carried out on the 150–250-μm fraction of G. bulloides collected from the tow samples. These samples were manually separated on-board, cleaned and stored. All samples were roasted under vacuum at 375 °C for 1 hour prior to isotopic analysis. Measurements of δ18O and δ13C values in both foraminifera and sea water were carried out at Indian Institute of Science (Bangalore) using a Gas bench II peripheral coupled with our Thermo Fisher- MAT 253 isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron, Bremen, GmbH)67. The decision to use Gas bench II peripheral was prompted by the small number (~10) of foraminifera specimens collected in towing where the amount of carbonate was not suitable for dual inlet analysis. The laboratory carbonate standard MARJ168 was used for routine calibration and the precision was 0.08‰ for δ18O and 0.05‰ for δ13C based on repeated analysis.

In order to compare equilibrium calcite δ18O and δ13C values against measured foraminiferal values we estimated the δ18O and δ13C of calcite precipitated in isotopic equilibrium with seawater as described in section 2.3.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Prasanna, K. et al. Isotopic disequilibrium in Globigerina bulloides and carbon isotope response to productivity increase in Southern Ocean. Sci. Rep. 6, 21533; doi: 10.1038/srep21533 (2016).

References

Kohfeld, K. E., Fairbanks, R. G., Smith, S. L. & Walsh, I. D. Neogloboquadrina pachyderma (sinistral coiling) as paleoceanographic tracers in polar oceans: Evidence from northeast water Polynya plankton tows, sediment traps, and surface sediments. Paleoceanography 11, 679–699, doi: 10.1029/96pa02617 (1996).

Fairbanks, R. G. & Wiebe, P. H. Foraminifera and chlorophyll maximum-vertical-distribution, seasonal succession, and paleoceanographic significance. Science 209, 1524–1526, doi: 10.1126/science.209.4464.1524 (1980).

Williams, D. F., Be, A. W. H. & Fairbanks, R. G. Seasonal stable isotopic variations in living planktonic-foraminifera from Bermuda plankton tows. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol 33, 71–102, doi: 10.1016/0031-0182(81)90033-x (1981).

Kahn, M. I. & Williams, D. F. Oxygen and Carbon isotopic composition of living planktonic-foraminifera from the Northeast Pacific-Ocean. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol 33, 47–69, doi: 10.1016/0031-0182(81)90032-8 (1981).

Hemleben, C., Spindler, M., Breitinger, I. & Deuser, W. Field and laboratory studies on the ontogeny and ecology of some Globorotaliid species from the Sargasso Sea off Bermuda. J Foraminiferal Res 15, 254–272 (1985).

Curry, W. B., Thunell, R. C. & Honjo, S. Seasonal-changes in the isotopic composition of Planktonic-foraminifera collected in Panama basin sediment traps. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 64, 33–43, doi: 10.1016/0012-821x(83)90050-x (1983).

Sautter, L. R. & Thunell, R. C. Seasonal variability in the δ18O and δ13C of planktonic foraminifera from an upwelling environment: sediment trap results from the San Pedro basin, Southern California Bight. Paleoceanography 6, 307–334, doi: 10.1029/91pa00385 (1991).

Sautter, L. R. & Thunell, R. C. Planktonic foraminiferal response to upwelling and seasonal hydrographic conditions - sediment trap results from San-Pedro-basin, Southern California Bight. J. Foraminiferal Res 21, 347–363 (1991).

Rahmstorf, S. Ocean circulation and climate during the past 120,000 years. Nature 419, 207–214 (2002).

Gupta, A. K., Anderson, D. M. & Overpeck, J. T. Abrupt changes in the Asian southwest monsoon during the Holocene and their links to the North Atlantic Ocean. Nature 421, 354–357 (2003).

Prell, W. L. In Climate Processes and Climate Sensitivity (eds James E. Hansen & Taro Takahashi ) (American Geophysical Union, 1984).

Curry, W., Ostermann, D., Guptha, M. & Ittekkot, V. Foraminiferal production and monsoonal upwelling in the Arabian Sea: evidence from sediment traps. Geol. S., London, Special Publications 64, 93–106 (1992).

Bé, A. W. H. & Hutson, W. H. Ecology of Planktonic Foraminifera and Biogeographic Patterns of Life and FossilAssemblages in the Indian Ocean. Micropaleontology 23, 369–414 (1977).

Fairbanks, R. G., Sverdlove, M., Free, R., Wiebe, P. H. & Be, A. W. H. Vertical-distribution and isotopic fractionation of living planktonic-foraminifera from the panama basin. Nature 298, 841–844, doi: 10.1038/298841a0 (1982).

Ortiz, N. Differential patterns of benthic foraminiferal extinctions near the Paleocene Eocene boundary in the North Atlantic and the western Tethys. Mar. Micropaleontol. 26, 341–359, doi: 10.1016/0377-8398(95)00039-9 (1995).

Hemleben, C. & Michael Anderson, O. Roger. Modern Planktonic Foraminifera. (Springer New York, 1989).

Friedrich, O. et al. Influence of test size, water depth, and ecology on Mg/Ca, Sr/Ca, δ18O and δ13C in nine modern species of planktic foraminifers. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 319, 133–145, doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2011.12.002 (2012).

Barcena, M. A. et al. Planktonic response to main oceanographic changes in the Alboran Sea (Western Mediterranean) as documented in sediment traps and surface sediments. Mar. Micropaleontol. 53, 423–445, doi: 10.1016/j.marmicro.2004.09.009 (2004).

Schiebel, R., Bijma, J. & Hemleben, C. Population dynamics of the planktic foraminifer Globigerina bulloides from the eastern North Atlantic. Deep-Sea Res. I 44, 1701–1713, doi: 10.1016/s0967-0637(97)00036-8 (1997).

Pujol, C. & Grazzini, C. V. Distribution patterns of live planktic foraminifers as related to regional hydrography and productive systems of the Mediterranean-Sea. Mar. Micropaleontol. 25, 187–217, doi: 10.1016/0377-8398(95)00002-i (1995).

Mohan, R., Shetye, S. S., Tiwari, M. & Anilkumar, N. Secondary Calcification of Planktic Foraminifera from the Indian Sector of Southern Ocean. Acta Geologica Sinica-English Edition 89, 27–37 (2015).

Orr, W. Secondary calcification in the foraminiferal genus Globorotalia. Science 157, 1554–1555 (1967).

Duplessy, J. C., Be, A. W. H. & Blanc, P. L. Oxygen and Carbon isotopic composition and biogeographic distribution of planktonic-foraminifera in the Indian-Ocean. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol 33, 9–46, doi: 10.1016/0031-0182(81)90031-6 (1981).

Elderfield, H., Bertram, C. J. & Erez, J. Biomineralization model for the incorporation of trace elements into foraminiferal calcium carbonate. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 142, 409–423, doi: 10.1016/0012-821x(96)00105-7 (1996).

Erez, J. The source of ions for biomineralization in foraminifera and their implications for paleoceanographic proxies. Biomineralization 54, 115–149, doi: 10.2113/0540115 (2003).

Martinez, J. I. Late Pleistocene paleoceanography of the Tasman Sea - Implications for the dynamics of the warm pool in the Western Pacific. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol 112, 19–62, doi: 10.1016/0031-0182(94)90133-3 (1994).

Prasanna, K., Ghosh, P. & Kumar, A. Stable isotopic signature of Southern Ocean deep water CO2 ventilation. Deep-Sea Res. II 118, 177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2015.04.009 (2015)

Pollard, R. T., Lucas, M. I. & Read, J. F. Physical controls on biogeochemical zonation in the Southern Ocean. Deep-Sea Res. II 49, 3289–3305, doi: 10.1016/s0967-0645(02)00084-x (2002).

Racape, V., Lo Monaco, C., Metzl, N. & Pierre, C. Summer and winter distribution of δ13C (DIC) in surface waters of the South Indian Ocean 20 degrees S-60 degrees S. Tellus B Chem Phys Meteorol 62, 660–673, doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0889.2010.00504.x (2010).

Belkin, I. M. & Gordon, A. L. Southern Ocean fronts from the Greenwich meridian to Tasmania. J Geophys Res-Oceans 101, 3675–3696, doi: 10.1029/95jc02750 (1996).

Holliday, N. P. & Read, J. F. Surface oceanic fronts between Africa and Antarctica. Deep-Sea Res. I 45, 217–238, doi: 10.1016/s0967-0637(97)00081-2 (1998).

Anilkumar, N., George, J. V., Chacko, R., Nuncio, N. & Sabu, P. Variability of fronts, fresh water input and chlorophyll in the Indian Ocean sector of the Southern Ocean. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshwater Res. 49, 20–40, doi: 10.1080/00288330.2014.924972 (2015).

Kostianoy, A. G., Ginzburg, A. I., Frankignoulle, M. & Delille, B. Fronts in the Southern Indian Ocean as inferred from satellite sea surface temperature data. J Mar Syst 45, 55–73, doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2003.09.004 (2004).

Khare, N. & Chaturvedi, S. K. Tracing the signature of various frontal systems in stable isotopes (oxygen and carbon) of the planktonic foraminiferal species Globigerina bulloides in the Southern Ocean (Indian Sector). Oceanologia 54, 311–323, doi: Doi 10.5697/Oc.54-2.311 (2012).

Shackleton, N. Oxygen isotopes, ice volume and sea level. Quat Sci Rev 6, 183–190 (1987).

Pearson, P. N. Oxygen isotopes in foraminifera: Overview and historical review. Paleontological Society Papers 18, 1–38 (2012).

Tiwari, M., Nagoji, S. S., Anilkumar, N. & Rajan, S. Oxygen isotope distribution at shallow to intermediate depths across different fronts of the Southern Ocean: Signatures of a warm-core eddy. Deep-Sea Res. II 118, 170–176 (2015).

Bemis, B. E., Spero, H. J., Lea, D. W. & Bijma, J. Temperature influence on the carbon isotopic composition of Globigerina bulloides and Orbulina universa (planktonic foraminifera). Mar. Micropaleontol. 38, 213–228, doi: 10.1016/s0377-8398(00)00006-2 (2000).

Zhang, J., Quay, P. D. & Wilbur, D. O. Carbon-Isotope fractionation during gas-water exchange and dissolution of CO2 . Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 59, 107–114, doi: 10.1016/00167-0379(59)1550d- (1995).

Talley, L. D. Hydrographic Atlas of the World Ocean Circulation Experiment (WOCE). Volume 4: Indian Ocean (eds. M. Sparrow, P. Chapman & J. Gould ). International WOCE Project Office, Southampton, UK, ISBN 0904175588 (2013).

Goericke, R. & Fry, B. Variations of marine plankton δ13C with latitude, temperature, and dissolved CO2 in the world ocean. Global Biogeochem Cycles 8, 85–90, doi: 10.1029/93gb03272 (1994).

Soares, M. A. et al. Latitudinal δ13C and δ15N variations in particulate organic matter (POM) in surface waters from the Indian ocean sector of Southern Ocean and the Tropical Indian Ocean in 2012. Deep-Sea Res. II 118, 186–196 (2015).

Zeebe, R. E. & Wolf-Gladrow, D. A. CO2 in seawater: equilibrium, kinetics, isotopes. Vol. 65 (Gulf Professional Publishing, 2001).

IPCC. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the IntergovernmentalPanel on Climate Change. (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Ducklow, H. W., Steinberg, D. K. & Buesseler, K. O. Upper ocean carbon export and the biological pump. OCEANOGRAPHY-WASHINGTON DC-OCEANOGRAPHY SOCIETY- 14, 50–58 (2001).

Henson, S. A. et al. A reduced estimate of the strength of the ocean’s biological carbon pump. Geophys Res Lett 38, doi: 10.1029/2011gl046735 (2011).

Laws, E. A., Falkowski, P. G., Smith, W. O., Ducklow, H. & McCarthy, J. J. Temperature effects on export production in the open ocean. Global Biogeochem Cycles 14, 1231–1246, doi: 10.1029/1999gb001229 (2000).

Tremblay, L., Caparros, J., Leblanc, K. & Obernosterer, I. Origin and fate of particulate and dissolved organic matter in a naturally iron-fertilized region of the Southern Ocean. Biogeosciences 12, 607–621, doi: 10.5194/bg-12-607-2015 (2015).

Sabine, C. L., Key, R. M., Feely, R. A. & Greeley, D. Inorganic carbon in the Indian Ocean: Distribution and dissolution processes. Global Biogeochem Cycles 16, doi: 10.1029/2002gb001869 (2002).

Schlitzer, R. Carbon export fluxes in the Southern Ocean: results from inverse modeling and comparison with satellite-based estimates. Deep-Sea Res. II 49, 1623–1644, doi: 10.1016/s0967-0645(02)00004-8 (2002).

Cayre, O. & Bassinot, F. Oxygen isotope composition of planktonic foraminiferal shells over the Indian Ocean: calibration to modern oceanographic data. Mineral Mag 62, 288–289 (1998).

Saraswat, R. & Khare, N. Deciphering the modern calcification depth of globigerina bulloides in the southwestern indian ocean from its oxygen isotopic composition. J.Foraminiferal Res. 40, 220–230 (2010).

Anilkumar, N. et al. Oceanic fronts along 45 degrees E across Antarctic Circumpolar Current during austral summer 2004. Curr. Sci. 88, 1669–1673 (2005).

Rosenthal, Y., Lohmann, G. P., Lohmann, K. C. & Sherrell, R. M. Incorporation and preservation of Mg in Globigerinoides sacculifer: Implications for reconstructing the temperature and O-18/O-16 of seawater. Paleoceanography 15, 135–145, doi: 10.1029/1999pa000415 (2000).

Lohmann, G. P. A model for variation in the chemistry of planktonic-foraminifera due to secondary calcification and selective dissolution. Paleoceanography 10, 445–457, doi: 10.1029/95pa00059 (1995).

Dekens, P. S., Lea, D. W., Pak, D. K. & Spero, H. J. Core top calibration of Mg/Ca in tropical foraminifera: Refining paleotemperature estimation. Geochem. Geophy. Geosy. 3, doi: 10.1029/2001gc000200 (2002).

Brown, S. J. & Elderfield, H. Variations in Mg/Ca and Sr/Ca ratios of planktonic foraminifera caused by postdepositional dissolution: Evidence of shallow Mg-dependent dissolution. Paleoceanography 11, 543–551, doi: 10.1029/96pa01491 (1996).

Spero, H. J., Bijma, J., Lea, D. W. & Bemis, B. E. Effect of seawater carbonate concentration on foraminiferal carbon and oxygen isotopes. Nature 390, 497–500, doi: 10.1038/37333 (1997).

Erez, J. Vital effect on Stable-isotope composition seen in foraminifera and coral skletons. Nature 273, 199–202, doi: 10.1038/273199a0 (1978).

Gruber, N. et al. Spatiotemporal patterns of carbon-13 in the global surface oceans and the oceanic Suess effect. Global Biogeochem Cycles 13, 307–335, doi: 10.1029/1999gb900019 (1999).

Keeling, C. D., Whorf, T. P., Wahlen, M. & Vanderplicht, J. Interannual extremes in the rate of rate of rise of atmospheric Carbon-Dioxide since 1980. Nature 375, 666–670, doi: 10.1038/375666a0 (1995).

McNeil, B. I., Matear, R. J. & Tilbrook, B. Does carbon 13 track anthropogenic CO2 in the Southern Ocean? Global Biogeochem Cycles 15, 597–613, doi: 10.1029/2000gb001352 (2001).

Quay, P., Sonnerup, R., Westby, T., Stutsman, J. & McNichol, A. Changes in the C-13/C-12 of dissolved inorganic carbon in the ocean as a tracer of anthropogenic CO2 uptake. Global Biogeochem Cycles 17, doi: 10.1029/2001gb001817 (2003).

Kucera, M. & Darling, K. F. Cryptic species of planktonic foraminifera: their effect on palaeoceanographic reconstructions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London Series a-Mathematical Physical and Engineering Sciences 360, 695–718, doi: 10.1098/rsta.2001.0962 (2002).

Darling, K. F. & Wade, C. M. The genetic diversity of planktic foraminifera and the global distribution of ribosomal RNA genotypes. Mar. Micropaleontol. 67, 216–238, doi: 10.1016/j.marmicro.2008.01.009 (2008).

Wiebe, P. H. A multiple opening/closing net and environment sensing system for sampling zooplankton. J. Mar. Res. 34, 313–326 (1976).

Rangarajan, R. & Ghosh, P. Role of water contamination within the GC column of a GasBench II peripheral on the reproducibility of O-18/O-16 ratios in water samples. Isotopes Environ Health Stud 47, 498–511, doi: 10.1080/10256016.2011.631007 (2011).

Wendeberg, M., Richter, J. r. M., Rothe, M. & Brand, W. A. δ18O anchoring to VPDB: calcite digestion with 18O-adjusted ortho-phosphoric acid. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 25, 851–860 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Ministry of Earth Science, Government of India for providing financial support for the Indian Scientific Expedition to the Indian Ocean sector of the Southern Ocean, under which the present work was carried out. We also thank the Director, NCAOR, Goa, and the Director of Divecha Centre for Climate Change, Bangalore, for providing the necessary facilities and support. We thank all the scientific team, Captain, officers and crew on-board ORV SagarNidhi for their support during the sampling.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.G. and K.P. conceived the idea and executed the project, K.M. did the foraminifera separation in the cruise along with and K.P. and N.A. coordinated and supported the project as part of the southern ocean expedition, and K.P., S.K.B. and P.G. developed the model and jointly wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Prasanna, K., Ghosh, P., Bhattacharya, S. et al. Isotopic disequilibrium in Globigerina bulloides and carbon isotope response to productivity increase in Southern Ocean. Sci Rep 6, 21533 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21533

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21533

This article is cited by

-

Adaptive ecological niche migration does not negate extinction susceptibility

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.