Abstract

The realization of phase discontinuities across metasurfaces has led to a new class of reflection and refraction. Here we present theory and experiment on the discontinuous propagation of wavepackets across subwavelength-thickness meta-atoms. Using acoustic waves, we observe the process of wavepackets traversing a meta-atom with abrupt displacements, which appear as path discontinuities on a space-time diagram. We construct a tunable meta-atom from two coupled resonators at ~500 Hz, map the spatiotemporal trajectories of individual sonic pulses and reveal discontinuities at the meta-atom where the pulses exit at a time ~50 ms ahead or behind their arrivals. Applications include thin acoustic metasurface lenses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metamaterials are artificial structures engineered on a sub-wavelength level to produce exotic wave propagation characteristics1,2,3,4,5. Ranges of constitutive parameters exhibited by their bulk forms have been extended to beyond classically available ranges in both electromagnetism and acoustics: single and double negativity as well as a wide range of double-positive parameters have brought many remarkable phenomena into reality, including negative refraction, reverse Doppler effect, superlensing and cloaking6,7,8,9.

Recently a new direction for metamaterials research has emerged by the introduction of metasurfaces10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. Holloway et al.10 define a metasurface as any array of metamaterial unit-cells (meta-atoms) on a surface for which the thickness and periodicity are small compared to the wavelength in the surrounding media. For the simplest case of one-dimensional (1D) waves propagating in a waveguide, a metasurface is represented by a dot, or single meta-atom10. With significantly smaller loss, metasurfaces produce abrupt phase and amplitude changes, enabling new mechanisms for refraction, polarization conversion and beam shaping15,16,17,18,19,20,21.

Despite intensive investigations on abrupt phase shifts, few studies have been reported on the explicit action of metasurfaces on wavepackets, there having been only one reported case of the direct observation of wavepackets passing through a metasurface: Dolling et al.26 measured an abrupt advancement of the group time-shift across an electromagnetic metasurface in the near-infrared. However, a detailed picture of the transmission process in the vicinity of the metasurface was not obtained. Here we present the first spatiotemporal measurement of a wavepacket as it propagates across a meta-atom. To achieve this we use an acoustic system consisting of a tunable meta-atom made up of two coupled resonators.

Geometry and theory of the acoustic meta-atom

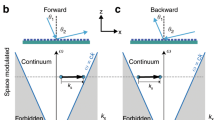

We start by briefly reviewing pulse transmission through a dispersive medium or an impedance boundary with dispersive transmission characteristics27, showing analytically that metasurfaces producing a phase discontinuity for monochromatic waves also engender an abrupt displacement for passing wavepackets. This analysis applies to both electromagnetic and acoustic waves. The phase shift δ across a metasurface exhibits a strong dispersion. Therefore, the beat pattern resulting from the generic case of the superposition of two monochromatic waves of nearby frequency is altered by the difference in phase shift as they traverse the metasurface. Figure 1 shows schematically the case of a higher frequency wave at angular frequency ωh encountering greater phase advancement δ than a lower frequency wave at ωl [see Fig. 1a]. In this case it is straightforward to show that the temporal advance of the envelope τg [see Fig. 1b] is given by τg = Δδ/Δω.

Schematic diagram illustrating the origin of an abrupt discontinuity at a metasurface by means of the simultaneous transmission of two monochromatic waves of different frequencies ωl and ωh.

(a) Here, the higher frequency component p1 experiences more phase advancement than the lower frequency component p2 as the waves pass through the metasurface, resulting in (b) a temporal shift in the beat pattern. The blue dotted curve in (b) represents two frequencies with the same phase shift. The red solid curve in (b) represents the case when the higher frequency component experiences more phase advancement.

For the more general case of a wavepacket of central frequency ωc and amplitude pI (t) = m (t) cos (ωct) = m(t)Re{exp(−iωct)} at the position of the metasurface, where m(t) is a slowly varying envelope function, the complex form of the transmitted wavepacket  (t) is

(t) is

where PI (ω) is the Fourier transform of  (t) and T(ω) is the complex transmission coefficient. If the spectral width of the wavepacket Δω is sufficiently narrow, T(ω) can be approximated to first order as T(ω) ≈ |T(ωc)| exp(iτpωc − iτg(ω − ωc)), where τp = δ(ωc)/ωc and τg = dδ/dω are respectively the phase shift and the group time-shift evaluated at the frequency ωc. Here we are assuming that the transmission amplitude does not vary much over the spectral width of the pulse, Δω. Substituting for T(ω) in the above equation, we have

(t) and T(ω) is the complex transmission coefficient. If the spectral width of the wavepacket Δω is sufficiently narrow, T(ω) can be approximated to first order as T(ω) ≈ |T(ωc)| exp(iτpωc − iτg(ω − ωc)), where τp = δ(ωc)/ωc and τg = dδ/dω are respectively the phase shift and the group time-shift evaluated at the frequency ωc. Here we are assuming that the transmission amplitude does not vary much over the spectral width of the pulse, Δω. Substituting for T(ω) in the above equation, we have

The transmitted wavepacket is therefore given by

Clearly, the envelope of the exiting wavepacket has the same shape and is temporally advanced by the amount

If the slope is positive, the wavepacket peak transmits in advance of its arrival, whereas if the slope is negative, it transmits with a delay.

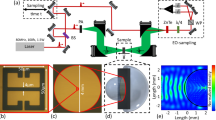

As the wavepacket experiences a sudden temporal shift τg, it also experiences a spatial jump, the position of the exiting wavepacket being shifted by the amount η = c0τg, where c0 is the phase velocity in the surrounding medium. Here we present observations of the process of wavepackets passing through a meta-atom with a spatiotemporal jump at ~500 Hz by constructing the acoustic meta-atom shown in Fig. 2a. Two acoustic resonators A and B are coupled by a cavity C, a system designed to emulate an atomic system exhibiting electromagnetically induced transparency (EIT)28,29.

(a) Experimental acoustic meta-atom consisting of two subwavelength-sized membrane-based resonators A and B coupled via cavity C. (b) Experimental setup for transmission-coefficient and pulse-delay measurements. The acoustic waves from the source propagate along the duct, through the meta-atom and are absorbed at the other end.

Resonator A is made from an 80 mm section of 15.5 mm inner-diameter tube with a thin (~10 μm thick) tensioned polyethylene membrane at one end. This end of the tube is connected to the coupling cavity C of length 51.8 mm and inner diameter 88 mm, whereas the other end is open to a one dimensional acoustic medium–a duct of diameter 30 mm–so that it interacts with external acoustic waves. The quality factor for resonator A, ~45, is comparable to that of typical Helmholtz resonators30. Resonator B consists of a cavity of tunable length ~200 ± 50 mm and diameter 32.7 mm and a mass-loaded membrane of the same type as in A. Tunable metasurfaces mimicking EIT-like effects have only previously been demonstrated for electromagnetic systems31,32,33. The Q-factor of the resonator B is ~140, which is significantly better than that of typical acoustic resonators such as resonating ducts and Helmholtz resonators30.

We shall derive the dynamics of this system with a lumped-element approximation34, appropriate here since the characteristic geometrical parameters are small compared with our acoustic wavelengths (λ~0.68 m). The air in tube A can be considered to move uniformly and its displacement ξA(t) in the direction of the open end is given by

where p(t) and pC are the pressures at the tube-A mouth and in the cavity C, respectively and the effective mass mA is the sum of the masses  of the air in the tube and the membrane A. Here, ρ0, SA and

of the air in the tube and the membrane A. Here, ρ0, SA and  are the density of air, the cross section and the effective length of the tube, respectively. (See the Supplementary Information for further experimental details.) Also, kA0 and bA are the spring constant of the membrane and the drag coefficient of the air in the tube, respectively. Resonator A emits acoustic waves to the duct and so represents a “radiative” resonator28. For convenience we shall include the radiation damping into the drag coefficient bA. Resonator B has spring constant kmemB5 and thus its net spring constant is kB0 = kmemB + kair. The contribution of the elasticity of the air in the tube B is

are the density of air, the cross section and the effective length of the tube, respectively. (See the Supplementary Information for further experimental details.) Also, kA0 and bA are the spring constant of the membrane and the drag coefficient of the air in the tube, respectively. Resonator A emits acoustic waves to the duct and so represents a “radiative” resonator28. For convenience we shall include the radiation damping into the drag coefficient bA. Resonator B has spring constant kmemB5 and thus its net spring constant is kB0 = kmemB + kair. The contribution of the elasticity of the air in the tube B is  , where VB is the volume of this tube. The displacement ξB (t) is given by

, where VB is the volume of this tube. The displacement ξB (t) is given by

where the effective mass mB is the sum of the loaded mass, the membrane and the air moving with the membrane, bB is the drag coefficient and SB is the cross section of the tube. Here mA and mB are estimated to be 0.0233 and 0.56 g, respectively. The loaded mass on the resonator B membrane is estimated to be 0.34 g. Resonator B is not directly coupled to the duct and so represents a “dark” resonator28. The pressure pC is related to ξA and ξB as follows:

where B0 is the bulk modulus of air.

Equations (2)–(4) can be rewritten in the form

where  ,

,  are acoustic inertances,

are acoustic inertances,  ,

,  , kC = B0/VC are acoustic stiffnesses,

, kC = B0/VC are acoustic stiffnesses,  ,

,  are acoustic drag coefficients of the resonators A and B and VC is the cavity volume C. These equations have the classical form of an EIT system28. If, in the uncoupled state, A and B are set to have the same resonance frequency, the coupling through the cavity C removes the degeneracy and results in a split resonance response and a consequent sharp phase dispersion. In practice A and B are set to have similar uncoupled resonant frequencies.

are acoustic drag coefficients of the resonators A and B and VC is the cavity volume C. These equations have the classical form of an EIT system28. If, in the uncoupled state, A and B are set to have the same resonance frequency, the coupling through the cavity C removes the degeneracy and results in a split resonance response and a consequent sharp phase dispersion. In practice A and B are set to have similar uncoupled resonant frequencies.

The pressure should be continuous, so pi + pr = pt, where pi, pr and pt are the pressures of the incident, reflected and transmitted waves, respectively. Using the reflection and transmission coefficients R = pr/pi and T = pt/pi, one obtains the relation 1 + R = T. Also, the particle-velocity boundary condition is determined by equating the volume velocities into and out of the meta-atom:

where Sduct is the cross-sectional area of the duct and the particle velocities of the incident, reflected and transmitted waves are defined as ui, ur and ut, respectively. From the acoustic impedance relations, ui = pi/Z0, ur = −pr/Z0 and ut = pt/Z0, Eq. (6) becomes

where  is the impedance of air. These relations yield the acoustic-amplitude transmission coefficient:

is the impedance of air. These relations yield the acoustic-amplitude transmission coefficient:

An analytical expression for T can be obtained from the particle velocity  by solving the coupled equations of motion for the system, Eqs. (5), under sinusoidal excitation conditions (see the Supplementary Information).

by solving the coupled equations of motion for the system, Eqs. (5), under sinusoidal excitation conditions (see the Supplementary Information).

Results

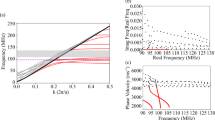

Equation (8) predicts a phase discontinuity across the meta-atom. To investigate this experimentally we measured T(ω) = |T(ω)|exp(−iδ (ω)) for monochromatic waves, where |T(ω)| and δ(ω) are the magnitude and phase advance, respectively, over the frequency range 400 to 600 Hz using the setup shown in Fig. 2b, with microphones placed 160 mm away either side of the meta-atom. The data for lB = 195 mm (VB = 163.8 cm3) are shown in Fig. 3a by the dots. The solid (red) theoretical curves are obtained from the solutions of Eq. (8). These curves, based on measured and fitted parameters (see Supplementary Information), agree with the experiment with only minor differences, the differences presumably stemming from the approximate nature of the lumped-element approximation and the effective lengths.

(a) Dots: measured magnitude |T| (ω) and phase advance δ (ω) of the transmission coefficient for fixed lB = 195 mm (VB = 163.8 cm3). Solid red curves: theoretical fits. (b) Time-domain measurements of the incident (larger, blue pulses) and transmitted (smaller, red pulses) acoustic pressure amplitude for the same VB. The Gaussian wavepackets have central frequencies 506 and 512 Hz, corresponding to maximum-negative and maximum-positive group shifts. The operating frequencies are marked as the green solid circles p and q in (a). (c) Measured space-time diagrams of the normalized pressure amplitude for positive and negative group delay. The volume VB was fixed to 170.5 cm3 and a single temporally-Gaussian pulse of spectral width 3 Hz was generated and recorded by a microphone scanned along the tube.

It is evident that our system can produce phase discontinuities ~±1 radian for a single meta-atom, analogous to those seen (up to ±π rad11,17,21) in electromagnetic metasurfaces or atomic systems. Our system provides a group-time shift, which is important in broadband lensing applications35. However, for full control of the waves, additional measures may be needed because the span of the phase shift δ in our system is not optimal for redirecting beams. Group shifts were measured by comparing the time differences of the peaks for the incident and transmitted pulses. Figure 3b shows the results of experiments with Gaussian wavepackets of spectral width 3 Hz for respectively, the group shift as a function of frequency and the pressure amplitude as a function of time at the central frequencies 506 and 512 Hz, corresponding respectively to the the green solid circles p and q in Fig. 3a. The incident and transmitted wavepackets are shown in blue (larger pulses) and red (smaller pulses), respectively. At 506 Hz, the peak of the transmitted pulse is delayed by 54.0 ms (having the same shape but with reduced height), whereas at 512 Hz it is advanced by 40.3 ms.

To access the full spatiotemporal field, we measured the time evolution of the pressure distribution in the tube near the meta-atom before and after the wavepacket passes through it. The results are shown in the normalized space-time diagrams of Fig. 3c. A discontinuity is clearly seen at the position z = 0 of the meta-atom. The trajectories for incident, reflected and transmitted pulses far (>λ) from the meta-atom were not measured, but should be straight lines with slopes ±c0, where c0 = 340 m/s is the speed of sound. At the position of the meta-atom, the space-time trajectory makes temporal steps up to −54 ms and 36 ms. These steps occur over a distance ~0.02 m (~0.03λ), governed by the diameter (15.5 mm) of the radiative resonator. This spatiotemporal observation of a positive temporal step provides a first detailed view of the “supersonic” transmission of pulses through a subwavelength-thickness meta-atom, analogous to that of “superluminal” propagation of light through a microscopic interface. Negative group delay here does not imply causality violation. It just means that the peak of the transmitted wavepacket appears before the arrival of the peak of the incident one. As demonstrated in earlier works36, this is because the peak of the transmitted wavepacket is not causally connected to that of the incident one: more energy of the wavepacket is absorbed from the rear part than from the front part.

Group shifts in metasurfaces consisting of resonating meta-atoms result from rapid changes in phase shift δ near the resonance frequencies. Clearly, for maximum group shift the meta-atoms should be designed for maximum |dδ/dω|. Our structure exhibits a maximum group shift |τg| ≈54 ms, corresponding to the distance |c0τg| ≈18 m, or 27λ. Our work greatly improves on the magnitude of the discontinuity compared to the value of 4λ reported by the time-domain measurements of Dolling et al.26.

For the case of optical pulses used for digital communications, the pulse widths are approximately equal to the coherence length. When metasurface lenses are used to refocus such broadband pulses, the path lengths for rays passing through different parts of the metasurface are different. To compensate the path differences it is necessary to provide appropriate group shifts τg which vary with position over a wide tuning range. We tuned the group shift of our meta-atom for a fixed central frequency of 500 Hz by adjusting the resonance frequency of the dark oscillator, i.e., resonator B, via the cavity volume VB, as shown by the results of Fig. 4a. The measured incident (larger, blue) and transmitted (smaller, red) wavepackets are plotted in Fig. 4b and are marked by the green solid squares in Fig. 4a. Here the group shift is tunable from −55 ms (slightly better than our previous −54 ms) to 29 ms, corresponding to a path difference of ~42λ. This range is ample for applications to metasurfaces functioning as thin sonic lenses. 3D plots of |T| and δ as a function of frequency and VB are given in Fig. 4c. The curves for a fixed frequency of 500 Hz are redrawn in the insets.

(a) Measured group shift at the central frequency 500 Hz as a function of the volume of the resonator B, showing a continuous tuning range from −55 to 29 ms, equivalent to a range of c0τg = 42λ. (b) Time-domain measurements of the incident (larger, blue pulses) and transmitted (smaller, red pulses) acoustic pressure amplitude at chosen values of VB marked by the green solid squares in (a). (c) Measured amplitude and phase advance measured across the meta-atom at various frequencies and volumes VB. The curves for a fixed frequency of 500 Hz are redrawn in the insets.

Discussion

As previously mentioned, negative group delay in electromagnetism or acoustics ushers in the possibility of “superluminal” or “supersonic” propagation. For electromagnetic pulses this is experimentally well established37,38,39,40. Researchers sometimes account for such effects in metasurfaces from the effective bulk constitutive parameters, by regarding single-layer metasurfaces as slabs of metamaterials with defined thicknesses. However, problems arise from the artificial character of the definition of such thicknesses that obscure, at a fundamental level, the localized effects at work at the sample boundaries10. Instead of bulk parameters such as permittivity, permeability, density or modulus, all that needs to be known to characterize a metasurface are the delay and attenuation engendered: in Ref. 10 it was shown that metasurfaces are well described by modelling them as sheets of zero thicknesses that abruptly change the phases and amplitudes of the reflected and transmitted waves owing to the scattering characteristics of the resonant meta-atoms. Our spatiotemporal pressure measurements clearly support this picture. It would be interesting to extend this research to acoustic-field spatiotemporal imaging of waves passing through metasurfaces and to electromagnetic-field spatiotemporal imaging in analogous EIT-like systems; several reported electromagnetic metamaterials mimicking EIT are of planar form31,32,33,41,42. Therefore, this electromagnetic-field imaging should be feasible using similar structures.

In conclusion, we have analytically and experimentally demonstrated that meta-atoms producing phase discontinuities for monochromagnetic waves also produce discontinuities in the space-time trajectories of wavepackets. Our tunable experimental design, based on coupled radiative and dark acoustic oscillators mimicking an EIT system, allows us to observe transmitted pulses at ~500 Hz that leave the meta-atom with group shifts in the range −55 ms to 40 ms, corresponding to record values of the normalized time-shift −28 < c0τg/λ < 20 for a room-temperature metamaterial system. A lumped-element model accurately describes the underlying dispersion. Observation of the entire process of the wavepackets exiting the meta-atom both ahead and behind of their arrivals with space-time diagrams accurately reveals the discontinuities represented by the group time-shift τg = dδ/dω. This work opens the way to practical focusing devices for acoustic waves based on 2D arrays22,23 of our meta-atom and to novel applications in beam steering and wavefront shaping not only in the audio range but also for analogous systems at ultrasonic frequencies.

Methods

A 10 W loudspeaker driven by a function generator provides sinusoidal or pulsed excitation at 1 m distance from the meta-atom. For the anechoic termination we used 60 m lengths of 30 mm diameter corrugated tubes attached to both ends of the duct, each closed with a commercial air filter for automobiles (Hyundai 28113 37101) to prevent residual reflections.

As shown in Fig. 2b, the acoustic meta-atom is positioned in the center of the duct. Resonators A and B and cavity C are fashioned from plastic tubes and resonator B is fitted with a plunger to allow its volume to be tuned. The effective masses mA and mB of the resonators A and B are estimated to be 0.0233 and 0.56 g, respectively. The loaded mass on the resonator B membrane is estimated to be 0.34 g.

For the frequency domain measurements, probe microphones are set halfway up the duct, as shown in Fig. 2b. For the spatiotemporal measurements these probe microphones are scanned along the tube length to produce the space-time plots.

The envelopes of the Gaussian wavepackets of spectral width 3 Hz (full width at half maximum in the power spectrum) were extracted by taking the magnitudes of the Hilbert transform of the waveforms, a widely used demodulation scheme for amplitude-modulated signals43. Then the curves were fitted using a least-squares algorithm to find the peaks and the group shifts were then obtained from the differences.

References

Pendry, J. B., Holden, A. J., Robbins, D. & Stewart, W. Low frequency plasmons in thin-wire structures. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 10, 4785 (1998).

Pendry, J. B., Holden, A. J., Robbins, D. & Stewart, W. Magnetism from conductors and enhanced nonlinear phenomena. IEEE Trans. Microwave Theory Tech. 47, 2075–2084 (1999).

Smith, D. R., Padilla, W. J., Vier, D., Nemat-Nasser, S. C. & Schultz, S. Composite medium with simultaneously negative permeability and permittivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 4184 (2000).

Fang, N. et al. Ultrasonic metamaterials with negative modulus. Nat. Mater. 5, 452–456 (2006).

Lee, S. H., Park, C. M., Seo, Y. M., Wang, Z. G. & Kim, C. K. Acoustic metamaterial with negative density. Phys. Lett. A 373, 4464–4469 (2009).

Pendry, J. B. Negative refraction makes a perfect lens. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 3966 (2000).

Fang, N., Lee, H., Sun, C. & Zhang, X. Subdiffraction-limited optical imaging with a silver superlens. Science 308, 534–537 (2005).

Schurig, D. et al. Metamaterial electromagnetic cloak at microwave frequencies. Science 314, 977–980 (2006).

Lee, S. H., Park, C. M., Seo, Y. M. & Kim, C. K. Reversed Doppler effect in double negative metamaterials. Phys. Rev. B 81, 241102 (2010).

Holloway, C. L. et al. An overview of the theory and applications of metasurfaces: The two-dimensional equivalents of metamaterials. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 54, 10–35 (2012).

Pfeiffer, C. & Grbic, A. Metamaterial huygens' surfaces: Tailoring wave fronts with reflectionless sheets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 197401 (2013).

Monticone, F., Estakhri, N. M. & Alù, A. Full control of nanoscale optical transmission with a composite metascreen. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 203903 (2013).

Kildishev, A. V., Boltasseva, A. & Shalaev, V. M. Planar photonics with metasurfaces. Science 339 (2013).

Mei, J. et al. Dark acoustic metamaterials as super absorbers for low-frequency sound. Nat. Commun. 3, 756 (2012).

Merlin, R. Radiationless electromagnetic interference: Evanescent-field lenses and perfect focusing. Science 317, 927–929 (2007).

Grbic, A., Jiang, L. & Merlin, R. Near-field plates: Subdiffraction focusing with patterned surfaces. Science 320, 511–513 (2008).

Yu, N. et al. Light propagation with phase discontinuities: Generalized laws of reflection and refraction. Science 334, 333–337 (2011).

Aieta, F. et al. Aberration-free ultrathin flat lenses and axicons at telecom wavelengths based on plasmonic metasurfaces. Nano lett. 12, 4932–4936 (2012).

Yu, N. et al. A broadband, background-free quarter-wave plate based on plasmonic metasurfaces. Nano lett. 12, 6328–6333 (2012).

Grady, N. K. et al. Terahertz metamaterials for linear polarization conversion and anomalous refraction. Science 340, 1304–1307 (2013).

Yu, N. & Capasso, F. Flat optics with designer metasurfaces. Nat. Mater. 13, 139–150 (2014).

Li, Y., Liang, B., Gu, Z., Zou, X. & Cheng, J. Reflected wavefront manipulation based on ultrathin planar acoustic metasurfaces. Sci. Rep. 3, 2546 (2013).

Zhao, J., Li, B., Chen, Z. & Qiu, C. W. Manipulating acoustic wavefront by inhomogeneous impedance and steerable extraordinary reflection. Sci. Rep. 3, 2537 (2013).

Zhao, J., Li, B., Chen, Z. & Qiu, C. W. Redirection of sound waves using acoustic metasurface. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 151604 (2013).

Chen, P.-Y., Farhat, M., Guenneau, S., Enoch, S. & Alù, A. Acoustic scattering cancellation via ultrathin pseudo-surface. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 191913 (2011).

Dolling, G., Enkrich, C., Wegener, M., Soukoulis, C. M. & Linden, S. Simultaneous negative phase and group velocity of light in a metamaterial. Science 312, 892–894 (2006).

Withayachumnankul, W., Fischer, B. M., Ferguson, B., Davis, B. R. & Abbott, D. A systemized view of superluminal wave propagation. Proc. IEEE 98, 1775–1786 (2010).

Alzar, C. G., Martinez, M. & Nussenzveig, P. Classical analog of electromagnetically induced transparency. Am. J. Phys. 70, 37 (2002).

Santilln, A. & Bozhevolnyi, S. I. Acoustic transparency and slow sound using detuned acoustic resonators. Phys. Rev. B 84, 064304 (2011).

Moloney, M. J. Quality factors and conductances in Helmholtz resonators. Am. J. Phys. 72, 1035 (2004).

Gu, J. et al. Active control of electromagnetically induced transparency analogue in terahertz metamaterials. Nature Commun. 3, 1151 (2012).

Tamayama, Y. et al. Electromagnetic response of a metamaterial with field-gradient-induced transparency. Phys. Rev. B 82, 165130 (2010).

Tamayama, Y., Nakanishi, T. & Kitano, M. Variable group delay in a metamaterial with field-gradient-induced transparency. Phys. Rev. B 85, 073102 (2012).

Blackstock, D. T. Fundamentals of Physical Acoustics (John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2000).

Ajioka, J. & Ramsey, V. An equal group delay waveguide lens. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 26, 519–527 (1978).

Milonni, P. W. Fast light, Slow Light and Left-Handed Light (Institute of Physics, Bristol, 2005).

Nimtz, G. & Heitmann, W. Superluminal photonic tunneling and quantum electronics. Prog. Quantum Electron. 21, 81–108 (1997).

Chiao, R. Y. & Steinberg, A. M. Quantum optical studies of tunneling and other superluminal phenomena. Phys. Scr. 1998, 61 (1998).

Wang, L. J., Kuzmich, A. & Dogariu, A. Gain-assisted superluminal light propagation. Nature 406, 277–279 (2000).

Chu, S. & Wong, S. Linear pulse propagation in an absorbing medium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 48, 738 (1982).

Zhang, S., Genov, D. A., Wang, Y., Liu, M. & Zhang, X. Plasmon-induced transparency in metamaterials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 047401 (2008).

Liu, N. et al. Plasmonic analogue of electromagnetically induced transparency at the Drude damping limit. Nat. Mater. 8, 758–762 (2009).

Ziemer, R. E. & Tranter, W. H. Principles of Communications (John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2002).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (NRF-2013K2A2A4003469 and NRF-2013R1A5A1A95042044). We also acknowledge Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Education, Science, Sports and Culture.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. and O.B.W. wrote the main manuscript text. I.Y., S.L. and C.K.H. contributed to the measurements. S.L., I.Y., K.J.B.L., J.W.W., D.S.S., H.S.M. and O.B.W. contributed to the theory. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Spatiotemporal path discontinuities of wavepackets propagating across a meta-atom

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The images in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the image credit; if the image is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the image. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yoo, I., Han, C., Shin, DS. et al. Spatiotemporal path discontinuities of wavepackets propagating across a meta-atom. Sci Rep 4, 4634 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04634

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04634

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.