Abstract

Surface and soil core samples from northeast China were analyzed for Pu isotopes. The measured 240Pu/239Pu atomic ratios and 239 + 240Pu/137Cs activity ratios revealed that the global fallout is the dominant source of Pu and 137Cs at these sites. Migration behavior of Pu varying with land type and human activities resulted in different distribution of Pu in surface soils. A sub-surface maximum followed by exponential decline of 239 + 240Pu concentrations was observed in an undisturbed soil core, with a total 239 + 240Pu inventory of 86.9 Bq/m2 and more than 85% accumulated in 0 ~ 20 cm layers. While only half inventory of Pu was obtained in another soil core and no sub-surface maximum value occurred. Erosion of topsoil in the site should be the most possible reason for the significantly lower Pu inventory, which is also supported by the reported 137Cs profiles. These results demonstrated that Pu could be applied as an ideal substitute of 137Cs for soil erosion study in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the 1940s, plutonium isotopes have been produced and released into the environment due to human nuclear activities, including nuclear weapons testing (NWT), operation and accidents of nuclear power plants (NPPs), e.g. Chernobyl accident in 1986 and Fukushima accident in 20111,2,3,4, production and reprocessing of nuclear fuel, as well as other nuclear accidents, e.g. Kyshtym accident in Russia in 1957; aircraft accidents in Thule, Greenland in 1968 and in Polomares, Spain in 1966; and satellites SNAP-9A in 19645,6,7. Among the 20 isotopes of Pu, 239Pu and 240Pu with half-lives of 24110 yr and 6561 yr, respectively, are the most important ones due to their highly radiological toxicities and long-term persistence in the environment.

In the past decades, most researches on environmental Pu have focused on the evaluation of radiation risk in contaminated areas1,2,3,4,5,6,7, migration of Pu in the environment related to nuclear activities and waste repository8, dispersion of Pu in the contaminated aquatic system9,10, as well as the environmental behavior of Pu in the ecosystem for radioecology studies11,12,13. Based on the significantly different isotopic composition of Pu related to its production and releases, the measurement of isotopic ratios and decay products of Pu in the environmental materials can be used to identify its source term and age. For instance, 240Pu/239Pu atomic ratios for weapon-grade Pu are very low (0.01 ~ 0.07)5,6,7,10,13,14 while much higher values are expected in spent fuel of nuclear power plants (up to 0.2 ~ 0.8, depending on reactor type and burn-up of the fuel)2,3,4,10, as well as in atmospheric weapons testing fallout (0.14 ~ 0.24, with an average of 0.18)15,16,17.

The deteriorated soil erosion and associated sedimentation arising from human activities have become a serious problem in many developing countries including China, which causes land degradation, downstream sedimentation in fields, floodplains and water bodies, consequently affects water quality. Since the 1960s, radionuclides have been proven to be powerful tracers for soil erosion investigation18. Based on high association of 137Cs to soil particles (mainly minerals), global fallout 137Cs from NWT mainly conducted in later 1950s and beginning of 1960s has been widely used for soil erosion studies in the past decades18. However, due to its relatively short half-life (30.2 yr), the concentrations of global fallout 137Cs in the environment have decreased by a factor of more than 2 comparing to the levels in the 1970s due to its radioactive decay and this declined trend will continue. This makes the applications of 137Cs for investigations of soil erosion, transportation and sedimentation less sensitive at present and will become difficult in the future. Because of the long half-lives of 239Pu and 240Pu, their dominating source of nuclear weapons testing fallout worldwide, as well as their high retention and low mobility in soil, they were therefore suggested as ideal substitutes of 137Cs for investigation of soil erosion19,20,21,22. Especially, with the rapid development of sensitive measurement techniques using mass spectrometry including inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) and accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) in the recent years, application of Pu isotopes for this investigation becomes more attractive and competitive. Nonetheless, quantification of soil erosion using Pu isotopes has not yet been well established up to date and very few baseline data of Pu isotopes have been reported22,23,24,25. Although concentrations of Pu isotopes in surface soils have been measured in many sites worldwide in the past 40 years23,26,27, a few works on Pu distribution in Chinese soils (less than 15 sampling sites, mainly surface soils) have been reported28,29,30 and no data of Pu isotopes in soils from northeast China is available.

In the past years, nuclear activities including NWT in North Korea have caused a high concern on the radiation exposure to inhabitants in northeast China, where is close to North Korea. However, no observations regarding anthropogenic radionuclides including Pu in northeast China have been reported. With the rapid development of nuclear energy in China in the past 10 years, there are 4 NPPs with 11 units in operation and 7 NPPs with 20 units under construction. Among them, Hongyanhe NPP with 4 units located in Dalian, Liaodong Bay region, is going to be operated in 2014 and the first unit has already started to operate from February 2013. Releases of radioactive materials from NPPs are also a major concern of the local inhabitants, in this case monitoring radionuclides in the surrounding environment can provide necessary information to the authorities and public.

Liaodong Bay, located in northeast China, is an inner bay of Bohai Sea. Major rivers flowing through this region, include Liao, Daliao, Fudu, Lianshan, Yantai, Liugu, Xingcheng and Daling River. Through these rivers, a large amount of surface soil removed from their catchments is transported to and deposited in the Liaodong Bay31, which degrades the soil quality of the coastal region for agriculture purpose. The high sedimentation of the eroded soil in the Bay is indeed a big concern related to the ecosystem of the Liaodong Bay. Understanding the soil erosion processes and dynamics is a vital issue for controlling soil erosion and improving eco-environmental quality of the region.

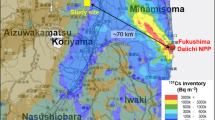

In this work, surface soil samples and soil cores were collected in the Liaodong Bay region (Fig. 1) and analyzed for 239Pu and 240Pu, in order (1) to provide basic information for environmental risk monitoring and evaluation related to the nuclear activities in North Korea and the Hongyanhe NPP; (2) to investigate the distribution, source term and environmental behavior of Pu in northeast China; (3) to establish Pu depth profile and inventory baseline, as well as to explore the feasibility of applying Pu in soil erosion studies in the region.

Results

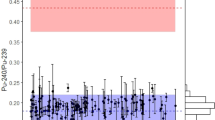

The results of activity concentrations of 239 + 240Pu and 137Cs, the atomic ratios of 240Pu/239Pu and the activity ratios of 239 + 240Pu/137Cs in all surface soil samples and two soil core samples were summarized in Supplementary Table S1 and Table S2 online, respectively. Data of 137Cs activity for all samples were cited from He et al32. A large variation of 239 + 240Pu concentrations from 0.023 to 0.938 mBq/g was observed in these surface soil samples (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S1 online). The statistical analysis (ANOVA) showed that Pu concentrations in surface soil from cultivated land (from 0.023 to 0.223 mBq/g with an average of 0.136 mBq/g) were significantly lower (p = 0.049 < 0.05) than those from grass land (from 0.027 to 0.938 mBq/g with an average of 0.361 mBq/g); whereas differences of Pu concentrations between cultivated and saline land, as well as saline and grass land, respectively, were not statistically significant, although their average Pu values followed the order of grass land (0.361 mBq/g) > saline land (0.211 mBq/g) > cultivated land (0.136 mBq/g). Figure 3 shows vertical distribution of 239 + 240Pu in the two soil cores (DL-01 and DL-02) collected in Dalian, Liaodong Bay. A sub-surface maximum of Pu concentration at 2 ~ 4 cm depth followed by exponentially decrease with depth until 16 cm was observed in the DL-01 soil core, while merely exponentially decreased Pu concentration from surface to 8 cm depth was observed in the DL-02 core. Similar depth profiles as DL-01 have also been reported in soil cores from Japan and South Korea11,24. The total 239 + 240Pu inventories in sampling sites of DL-01 and DL-02 were calculated by integrating the content of Pu in each layer of soil cores. The results (Table 1) indicated that about double 239 + 240Pu inventory (86.9 Bq/m2) in the sampling site of DL-01 compared to the sampling site of DL-02 (44.1 Bq/m2) was obtained. Since the two sampling sites are < 20 km distance, atmospheric deposition of Pu in these two sites should be similar. The difference in the total Pu inventory might only be attributed to different retention of Pu in these two sites.

Distribution of 239 + 240Pu activity concentration, 240Pu/239Pu atomic ratios and 239 + 240Pu/137Cs activity ratios in surface soils along the Liaodong Bay.

137Cs activities were cited from He et al.32 and decay corrected to 1st Sept. 2009. The horizontal dashed lines indicate the global fallout 240Pu/239Pu atomic ratio range of 0.18 ± 0.02. Vertical error bars correspond to analytical uncertainty (1σ).

Vertical distributions of 239 + 240Pu activity concentration and 240Pu/239Pu atomic ratios in soil cores ((a). DL-01 and (b). DL-02) from Dalian, northeast China.

The vertical dashed lines indicate the global fallout 240Pu/239Pu atomic ratio range of 0.18 ± 0.02. Horizontal error bars correspond to analytical uncertainty (1σ).

The measured 240Pu/239Pu atomic ratios in this work varied from 0.144 to 0.245 with an average of 0.192 ± 0.020 (1σ) in all surface samples, while in the two soil cores, the values ranged from 0.162 to 0.213 with an average of 0.187 ± 0.012 (1σ) in DL-01 core and from 0.146 to 0.209 with an average of 0.180 ± 0.021 (1σ) in DL-02 core, respectively, which were relatively constant and similar to those measured in the surface soils. Clearly, the measured 240Pu/239Pu ratios in all soil samples agreed very well with the value of 0.18 for the integrated global atmospheric fallout17, indicates that the major source of Pu in soils in northeast China might be the global atmospheric fallout.

Discussion

The sampling sites in this work located in northeast China (Fig. 1). There were no nuclear facilities operated in this region (<100 km to the sampling locations) before the sampling date (Oct. 2009). The nearest nuclear facilities were those located in Korea, which was more than 300 km far from the sampling sites. The atmospheric releases from nuclear activities in the North Korea including the nuclear reprocessing and underground NWT might have negligible contribution to Pu in the soil samples analyzed in this work. In addition, as a refractory element, Pu is not easily to be released to the atmosphere during underground NWT. Actually no radionuclide (even for volatile 85Kr, 133Xe, 131I) dispersion from the NWT in the North Korea has been observed in South Korea, Japan and China. As for the Chinese atmospheric NWT conducted in Lop Nor site (located in the Kumtag Desert, northwest China) during 1964 ~ 1980, the long distance between our sampling sites and Lop Nor (> 2600 km) probably made the close-in fallout Pu contribution from these NWTs insignificant to the Pu in soil samples analyzed in this work. Atmospheric release of Pu from NPPs in normal operation is very limited since almost all Pu isotopes are produced and captured in the fuel elements in the NPPs, therefore the contribution from the NPPs in remote areas in South Korea and South China (Tianwan, Qinshan and Dayawan NPPs, >550 km from the sampling locations) to the Pu in the soil samples investigated in this work is negligible. The dominant source of Pu in northeast China might be the global fallout of atmospheric NWT.

The measured 240Pu/239Pu atomic ratios in all soil samples in this work agreed very well with the reported values of the global fallout as well as those in similar latitude in China, such as soil samples from Gansu province (40°N, 97° E) of 0.169 ~ 0.192 with an average of 0.182 ± 0.008 (1σ)29 and from Hubei province (31°N, 112°E) of 0.172 ~ 0.22030. Similar 240Pu/239Pu atomic ratios of 0.157 ~ 193 with an average of 0.182 ± 0.012 (1σ) have also been reported in a sediment core collected in Lake Sihailongwan, northeast China (42°20′N, 126°50′E)33. In addition, the measured 239 + 240Pu/137Cs activity ratios (Supplementary Table S1 online) in all surface soil samples (~0.045, decay corrected to 1st Sept. 2009) agreed well with the reported values (0.030 ~ 0.043) in soils contaminated only by global atmospheric fallout34.

240Pu/239Pu atomic ratios of 0.403 ~ 0.412 of close-in fallout Pu derived from Chernobyl accident have been reported in soil samples heavily contaminated by Chernobyl accident collected in 30 km zone of Chernobyl2, the measured 240Pu/239Pu atomic ratios in all soil samples investigated in this work were about 2 times lower than these values. During the Chernobyl accident, most released radionuclides were deposited in the local area, some fraction of volatile radionuclides dispersed and deposited in the Europe and very small amount of radionuclides dispersed to other regions1,2,8,12,35,36,37. The inventory of 137Cs in the soil core DL-01 has been estimated to be 1.7 kBq/m232 which was more than 10 times lower than that in Germany (20 ~ 40 kBq/m2)37, while no measurable Chernobyl-derived Pu in the soil from west Europe has been reported. The 239 + 240Pu/137Cs activity ratios in surface soil samples in this work (~0.045, decay corrected to 1st Sept. 2009) were also 3 times higher than those measured in the Chernobyl contaminated soil (0.010 ~ 0.015, decay corrected to 2010)2. Based on these facts, it might be concluded that the direct contribution of the close-in fallout from Chernobyl accident to the Pu in soils in the northeast China should be negligible. Moreover, the reported 240Pu/239Pu atomic ratios of close-in fallout Pu in the Semipalatinsk NWT (0.04 ~ 0.07)14 (more than 3400 km distance to the present sampling locations), the Chinese NWT (0.08 ~ 0.103)33,38 and from the Kyshtym accident (0.0282 ± 0.0002)4,5 were all obviously lower than those (around 0.18) observed in this work, indicating that any close-in fallout contribution from these two NWT sites as well as from Kyshtym site could also be negligible in our sampling sites.

All above results suggested that Pu in the soils of northeast China should be primarily originated from the integrally global stratospheric fallout of the atmospheric NWT and the close-in fallout from any NWT sites and accidents is insignificant. The Hongyanhe NPP (39°47.5′N, 121°28.5′E) has just started in operation of its first unit from Feb. 2013. The measurement results in this work will provide a background data for the monitoring and evaluation of environmental impact of this NPP in the future.

A large variation in Pu concentrations (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S1 online) was observed in the surface soil samples. Since the analyzed soil samples were collected within a relatively small area (100 × 300 km) where no local input of Pu has been reported, the total input of Pu or the integral input of Pu from the global fallout should not vary significantly due to their similar climate and latitude. Therefore distinct retention, migration and removal behavior of Pu in different type of soil, as well as disturbance of soil column with varying degrees, should be major reasons causing high variation of Pu concentrations among surface soils collected from different sites. In the cultivated land, soils were heavily disturbed due to periodic cultivation activities; consequently, Pu from the atmospheric deposition to the surface soil was mixed with the soil in the deeper layer, which might cause a homogenized distribution of Pu in the plough horizon and decreased Pu concentration in the top soil. Meanwhile, irrigation of the cultivated land might leach and remobilize some Pu (water soluble fraction) from the soil thus reducing Pu levels in the surface soil. In addition, the cultivated land was seasonally covered by vegetation and a relatively high removal of the newly deposited Pu by wind was expected in a certain period of a year with lower vegetation coverage. All these factors contributed to lower Pu concentrations in surface soil from the cultivated land. Among these factors, the turnover of soil during the cultivation process causing the dilution of Pu by mixing the surface soil with deep soil might be the dominated reason. Similar observations have also been reported that Pu and 137Cs concentrations in the cultivated soil column were significantly lower than those found in undisturbed soil cores, meanwhile their distributions were rather constant in 0 ~ 10 cm layer in the cultivated soil column24. In grass land, grass roots reinforced the soil strength withstanding water flow flush and wind blow, thus effectively preventing surface soils from erosion, consequently Pu deposited on the soil could be effectively retained. In addition, the large surface area of vegetation leaves could also retain the Pu deposited from the atmosphere, which would be further transferred to the underneath soil by precipitation flushing or decomposition of the vegetation after death. The well retention and less removal of Pu in the grass land resulted in high Pu concentrations in its surface soil. As for the saline land with very low vegetation coverage, Pu deposited on the surface soil could be quickly removed by wind blow and runoff of precipitation, especially for small grains, resulting in Pu loss with varying degrees. Hence, different distribution of Pu in surface soil within a relatively small area might be mainly influenced by the pattern of land utilization. This phenomenon has also been reported for other fallout radionuclides including 7Be and 210Pb39.

Besides the high erosion of the surface soil in the low coverage land (such as saline land) and disturbance of the soil by agriculture activity in the cultivated land, the soil properties such as particle sizes, clay contents and organic matter contents might also influence the behavior of Pu in soils26,27, thus contribute to the variation of Pu concentrations. The surface soil samples analyzed in this work were collected from 5 different areas with distinct soil properties (Supplementary Table S3 online). However, regression analysis did not show any significant correlations between Pu concentrations and either grain size distributions or organic matter contents in these surface soil samples, implying that no single factor such as one parameter of soil properties but the joint-effect of many environmental factors is responsible for the variation of Pu concentrations in surface soils along the Liaodong Bay. Among all those factors, land utilization patterns resulting in somewhat changes of soil properties could be the dominated one.

Further insight into the environmental behavior of Pu in soils was provided by the distribution of Pu in the two soil cores. The sequential fractionation of radionuclides in soil has shown that Pu was mainly associated with organic matter and metal oxides, while 137Cs was mainly in minerals12,40. Therefore Pu might be relatively mobile in the soil, especially when Eh/pH of the soil was changed and decomposition of organic matter occurred. In addition, the relatively higher proportion of exchangeable and carbonate associated Pu compared to 137Cs has also been reported12,40. In the DL-01 soil core, although 80% ~ 90% of 239 + 240Pu and 137Cs accumulated in the top 20 cm soils, the relative inventory of 239 + 240Pu in the upper 6 cm soil (48%) was slightly lower than that of 137Cs (54%) (Table 1) and no sub-surface maximum of 137Cs in this soil core could be observed (Fig. 4a)32, agreeing well with the fractionation observation that Pu had a relatively higher mobility in soil compared to 137Cs40. Considering that the sampling site of the DL-01 core situated on the top of a broad hill with low possibilities of runoff or flowing, negligible erosion or deposition would be expected at this site. Possible reasons for the sub-surface maximum of Pu concentration at 2 ~ 4 cm in the DL-01 soil core (Fig. 3a, Fig. 4a) might include migration of Pu associated fine particles24 from surface to the sub-surface; accumulation of Pu associated organic matters (mainly humic or fulvic material) in the sub-surface layer and downwards migration of Pu caused by rainfall. However, clay contents and mean grain sizes in the two soil cores (Supplementary Fig. S1 online) varied slightly from layer to layer. Besides, the organic matter content in the sub-surface layer (2 ~ 4 cm) of the DL-01 core was not higher than that in the top layer (0 ~ 2 cm), although significant correlations (based on the regression analysis of ANOVA) were observed between organic matter contents and the concentrations of Pu and 137Cs, respectively (Fig. 5), indicating that fine particles and organic matter might not be responsible for the sub-surface maximum of Pu concentration in the DL-01 soil core. Therefore, the migration of Pu from the surface to the sub-surface should be induced by the adsorption and desorption process of Pu in the soil core driven by rain fallout.

Comparison between the profiles of 239 + 240Pu and 137Cs in the two soil cores ((a). DL-01 and (b). DL-02).

137Cs activities were cited from He et al.32 and decay corrected to 1st Sept. 2009. Horizontal error bars correspond to analytical uncertainty (1σ).

Correlation between the concentrations of Pu and 137Cs and organic matter contents in the two soil cores ((a). Pu ~ organic matter for soil core DL-01; (b). 137Cs ~ organic matter for soil core DL-01; (c). Pu ~ organic matter for soil core DL-02; (d). 137Cs ~ organic matter for soil core DL-02).

137Cs concentrations were cited from He et al.32 and decay corrected to 1st Sept. 2009. Vertical error bars correspond to analytical uncertainty (1σ).

In the DL-01 soil core, the activity ratios of 239 + 240Pu/137Cs tended to increase slightly with the increasing soil depth. An average 239 + 240Pu/137Cs activity ratio of 0.045 in the upper 6 cm layer agreed very well with the reported values (0.042 ~ 0.043, decay corrected to 1st Sept. 2009) in sites of a similar latitude (40° N) in USA34. However, the 239 + 240Pu/137Cs activity ratio increased to 0.079 (average) in deep layer (6 ~ 40 cm), which might resulted from a higher downwards migration of Pu compared to 137Cs due to the higher mobility of Pu. While in the DL-02 core, the 239 + 240Pu/137Cs activity ratios (0.038 ~ 0.109) throughout the soil core were generally higher than those reported values. In addition to the higher migration of Pu as mentioned above, another possible explanation for this might be linked to the out-flowing loss of fine particles enriched clay or materials absorbing higher amount of 137Cs in the surface layer, which was confirmed by lower inventory of 137Cs (45%) than Pu (51%) in the DL-02 core compared to the DL-01 core (Table 1).

Although the migration of Pu in the soil cores was higher than 137Cs, it was still a slow process and almost all Pu currently still remained in upper 50 cm (Fig. 3). As a consequence, strong correlations (based on the regression analysis of ANOVA) between the 137Cs and Pu isotopes in the two soil cores (R2 = 0.98, P = 1.8 × 10−10 for DL-01 core and R2 = 0.95, P = 6 × 10−10 for DL-02 core) were observed (Supplementary Fig. S2 online). High correlations between the concentrations of Pu and 137Cs were also observed in all surface samples in this work (Supplementary Fig. S3 online), especially in grass land (R2 = 0.95, P = 6 × 10−4), where the soil was less disturbed by human activities. The relatively low correlation between 137Cs and 239 + 240Pu concentrations in the cultivated land (R2 = 0.51, P = 0.005) might be attributed to high disturbance during cultivation activities. High correlation between 137Cs and Pu concentrations has also been reported in soils from other locations24,26,27. These results indicated that the physical transport of 239 + 240Pu and 137Cs in soils should be very similar despite their different chemical behaviors. Consequently, 239 + 240Pu and 137Cs could convey similar information about soil erosion and redistribution of soils in a small area.

Investigation of soil erosion using radionuclides is based on the principle that the radionuclides deposited on the soil surface are quickly and strongly adsorbed on the soil particles and then follow the physical processes of soil particles to be redistributed during soil erosion and sedimentation. To implement quantitative estimation of soil erosion and sedimentation rate from the measurement of radionculides, it is critical to establish the baseline or reference inventory of radionuclides in the investigated area. In the present work, the DL-01 soil core was collected at a stable and undisturbed site, where neither significant erosion nor additional deposition has been recorded. Based on the depth profile of Pu in the DL-01 soil core, the estimated total inventory of 239 + 240Pu of 86.9 ± 3.1 Bq/m2 (Table 1) agreed very well with those reported values in soil profiles in similar latitude (30 ~ 40°N) in Korea (84 ~ 88 Bq/m2)24. A slightly higher 239 + 240Pu inventory (101.8 Bq/m2) in Euiwang, Korea24, lower values in Hubei (44.9 ~ 54.6 Bq/m2)30 and Lanzhou (32.4 Bq/m2)29 in China have also been reported. The deviation of 239 + 240Pu inventory in the DL-01 core from those values might be attributed to the differences in the locations and climate of specific location. For example, the much higher precipitation rate in Dalian (600 ~ 800 mm)41 compared to that in Lanzhou (235 ~ 238 mm)29 could cause a relatively higher deposition of Pu and thus a higher inventory of 239 + 240Pu. In any case, the depth profile and total inventory of Pu in the soil core DL-01 could serve as reference inventory or baseline for further investigations in the sampling area.

The total inventory of 239 + 240Pu in the DL-02 core was measured to be 44.1 ± 0.9 Bq/m2 (Table 1), only half of the value in the DL-01 core. Since the distance between the two sampling sites are < 20 km, the atmospheric deposition of Pu in the two sites should not be significantly different. The erosion of soil at the DL-02 site might be the most possible reason for the significantly lower Pu inventory in this core. Comparing the Pu profiles in the two soil cores, the loss of Pu in the DL-02 core corresponded to the Pu in the first ~6 cm layer in the reference core (DL-01) (Table 1, Fig. 6a), deducing that the top ~6 cm soil at the site of DL-02 might be eroded. A similar conclusion could be also deduced based on the 137Cs profiles in the two soil cores (Table 1, Fig. 6b). This demonstrated that Pu could be used as a satisfied substitute of 137Cs for the investigation of soil erosion.

Comparison of 239 + 240Pu and 137Cs profiles between the two soil cores ((a). DL-01 and (b). DL-02).

137Cs activities were cited from He et al.32 and decay corrected to 1st Sept. 2009. Horizontal error bars correspond to analytical uncertainty (1σ).

The obvious spatial variation of Pu concentrations in the upper 5 cm soils (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S1 online) demonstrated that the surface soil was redistributed in different extents by erosion, transport and re-deposition processes in the studied area. However, to estimate the intensity of the erosion in a specific site of the area, more comprehensive work involving analyzing Pu profiles in a series of soil cores and modeling of downwards migration of Pu has to be carried out.

This is the first report of the 239 + 240Pu activities and 240Pu/239Pu atom ratios in soils in the northeast China. The present work demonstrated that fallout Pu could be an ideal substitute of the relatively short-lived fallout 137Cs for evaluation of soil erosion and redistribution in the future. The data sets provided background baseline for further monitoring and evaluation of anthropogenic Pu contamination in the area in case any unexpected releases of radionuclides from the Hongyanhe NPP or other NPPs in adjacent areas occur, as well as for quantitative studies on soil erosion in the region and the source identification of sediments in the Liaodong Bay in the following work.

Methods

Soil sampling

Soil samples were collected in Oct. 2009 in the coastal region of Liaodong Bay (Fig. 1), including five districts of Dalian (DL), Jinzhou (JZ), Panjin (PJ), Yingkou (YK) and Anshan (AS), which locate in a typical temperate zone dominated by a monsoonal climate with annual precipitation rate of 600 ~ 800 mm41 and annual mean temperature of 8.4 ~ 9.7°C42. Low hills and coastal plain are the major topographic characters in this region.

According to the vegetation coverage and utilization of the land at the sampling sites, all surface soil samples (0 ~ 5 cm) (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S3 online) collected can be sorted to three types, i.e. cultivated land (12 samples), grass land (6 samples) and saline land (3 samples). Soil cores collected in this region were analyzed for Pu isotopes, among them two cores (DL-01 and DL-02) up to 50 cm depth collected from Dalian were selected for investigating the feasibility of applying Pu isotopes for soil erosion studies. DL-01 sampling site (brown soil) situated on the top of a broad hill which was covered by native vegetation with dense bushes, without receiving obvious human disturbance. DL-02 sampling site was an un-cultured land with lower vegetation coverage. In the DL-01 soil core, lots of vegetation roots were observed distributing in the layer up to 35 cm, while fewer roots were observed in the DL-02 core. The two sampling sites are about 10 ~ 20 km distance from each other. The top 0 ~ 20 cm depth of the soil cores were sliced at 2 cm intervals and 20 ~ 50 cm depth at 5 cm intervals.

Soil analysis for Pu isotopes

Pu isotopes in all soils were determined using a modified method based on the method reported by Qiao et al.43 at the Center for Nuclear Technologies, Technical University of Denmark. An aliquot of 10 g prepared soil was first ashed at 550°C overnight to decompose the organic matter (as well as to obtain the organic matter content by calculating the mass-loss in this procedure). After spiking 242Pu as a chemical yield tracer and acid leaching with aqua regia for 2 hours under 200°C, Pu in the leachate was co-precipitated with iron hydroxides to remove major matrix components. After centrifugation, the precipitate was dissolved with a few milliliters of concentrated HCl, then redox pair of K2S2O5-NaNO2 was used to adjust overall Pu to Pu(IV). The final sample solution prepared in 8 mol/L HNO3 medium was loaded to an AG 1-×4 anion-exchange column (1 cm in diameter and 15 cm in length). After rinsing the column with 70 mL of 8 mol/L HNO3 to remove most uranium and matrix elements, followed by 50 mL of 9 mol/L HCl to remove thorium, Pu was eluted with 70 mL of 0.1 mol/L NH2OH·HCl in 2 mol/L HCl. The separated Pu was further purified using a 2-mL TEVA column (0.7 cm in diameter and 5 cm in length) to get better decontamination of uranium. Prior to the TEVA column purification, Pu was co-precipitated with Fe(OH)2 after adding 100 mg of Fe, then the precipitate was dissolved with 1.0 mL of concentrated HCl and concentrated HNO3 to oxidize Pu to Pu(IV), the sample was then diluted to 1 mol/L HNO3 and loaded to the TEVA column. After rinsing the column with 60 mL of 1 mol/L HNO3 and 60 mL of 6 mol/L HCl, Pu was finally eluted with 20 mL of 0.1 mol/L NH2OH·HCl in 2 mol/L HCl. The eluate was evaporated to dryness on a hot-plate followed by the addition of concentrated nitric acid and heating to decompose the hydroxylamine and eliminate the hydrochloric acid. The residue was finally dissolved in 5 mL of 0.5 mol/L HNO3 for measurements of Pu isotopes (239Pu, 240Pu, 242Pu) by an ICP-MS system (X Series II, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) equipped with an Xs- skimmer cone under hot plasma conditions. A high efficiency ultrasonic nebulizer (U5000AT+, CETAC, USA) was used for sample introduction to the ICP-MS. The detection limits were calculated as three times of the standard deviation (3σ) of the procedure blank to be 0.3 ~ 0.5 pg/L for 239Pu, 240Pu and 242Pu.

References

Onishi, Y., Voitsekhovich, O. V. & Zheleznyak, M. J. Chernobyl- what have we learned? (Springer, Amsterdam, 2007).

Muramatsu, Y. et al. Concentrations of 239Pu and 240Pu and their isotopic ratios determined by ICP-MS in soils collected from the Chernobyl 30-km zone. Environ. Sci. Technol. 34, 2913–2917 (2000).

Zheng, J. et al. Isotopic evidence of plutonium release into the environment from the Fukushima DNPP accident. Sci. Rep. 2, 304; 10.1038/srep00304 (2012).

Schneider, S. et al. Plutonium release from Fukushima Daiichi fosters the need for more detailed investigations. Sci. Rep. 3, 2988; 10.1038/srep02988 (2013).

Aarkrog, A. et al. Radioactive inventories from the Kyshtym and Karachay accidents: estimates based on soil samples collected in the South Urals (1990–1995). Sci. Total Environ. 201, 137–154 (1997).

Beasley, T. M. et al. Isotopic Pu, U and Np signatures in soils from Semipalatinsk-21, Kazakh Republic and the Southern Urals, Russia. J. Environ. Radioact. 39, 215–230 (1998).

Eriksson, M., Lindahl, P., Roos, P., Dahlgaard, H. & Holm, E. U, Pu and Am nuclear signatures of the Thule hydrogen bomb debris. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 4717–4722 (2008).

Matisoff, G. et al. Downward migration of chernobyl-derived redionuclides in soils in Poland and Sweden. Appl. Geochem. 26, 105–115 (2011).

Aston, S. R. & Stanners, D. A. Plutonium transport to and deposition and immobility in Irish Sea intertidal sediments. Nature 289, 581–582 (1981).

Lindahl, P. et al. Temporal record of Pu isotopes in inter-tidal sediments from the northeastern Irish Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 409, 5020–5025 (2011).

Yamamoto, M., Yamamori, S., Komura, K. & Sakanoue, M. Behavior of plutonium and americium in soils. J. Radiat. Res. 21, 204–212 (1980).

Lujaniene, G. et al. Study of 137Cs, 90Sr, 239,240Pu, 238Pu and 241Pu behavior in the Chernobyl soil. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 251, 59–68 (2002).

Taylor, R. N. et al. Plutonium isotope ratio analysis at femtogram to nanogram levels by multicollector ICP-MS. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 16, 279–284 (2001).

Yamamoto, M., Tsumura, A., Katayama, Y. & Tsukatani, T. Plutonium isotopic composition in soil from the former Semipalatinsk nuclear test site. Radiochim. Acta 72, 209–215 (1996).

Krey, P. W. et al. Mass isotopic composition of global fallout plutonium in soil. IAEA-SM-199/39, (International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, 1976).

Koide, M., Bertineb, K. K., Chowa, T. J. & Goldberga, E. D. The 240Pu/239Pu ratio, a potential geochronometer. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 72, 1–8 (1985).

Kelley, J. M., Bond, L. A. & Beasley, T. M. Global distribution of Pu isotopes and 237Np. Sci. Total Environ. 237/238, 483–500 (1999).

Zapata, F. & Nguyen, M. L. Environmental Radionuclides: Tracers and Timers of Terrestrial Processes (Elsevier, Amsterfam, 2010).

Schimmack, W., Auerswald, K. & Bunzl, K. Can 239 + 240Pu replace 137Cs as an erosion tracer in agricultural landscapes contaminated with Chernobyl fallout? J. Environ. Radioact. 53, 41–57 (2001).

Everett, S. E., Tims, S. G., Hancock, G. J., Bartley, R. & Fifield, L. K. Comparison of Pu and 137Cs as tracers of soil and sediment transport in a terrestrial environment. J. Environ. Radioact. 99, 383–393 (2008).

Tims, S. G., Everett, S. E., Fifield, L. K., Hancock, G. J. & Bartley, R. Plutonium as a tracer of soil and sediment movement in the Herbert River, Australia. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B 268, 1150–1154 (2010).

Hoo, W. T., Fifield, L. K., Tims, S. G., Fujioka, T. & Mueller, N. Using fallout plutonium as a probe for erosion assessment. J. Environ. Radioact. 102, 937–942 (2011).

Hardy, E. P., Krey, P. W. & Volchok, H. L. Global inventory and distribution of fallout plutonium. Nature 241, 444–445 (1973).

Lee, M. H., Lee, C. W., Hong, K. H., Choi, Y. H. & Boo, B. H. Depth distribution of 239,240Pu and 137Cs in soils of South Korea. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. Art 204, 135–144 (1996).

Tims, S. G., Fifield, L. K., Hancock, G. J., Lal, R. R. & Hoo, W. T. Plutonium isotope measurements from across continental Australia. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B 294, 636–641 (2013).

Lee, M. H., Lee, C. W. & Boo, B. H. Distribution and characteristics of 239,240Pu and 137Cs in the soil of Korea. J. Environ. Radioact. 37, 1–16 (1997).

Kim, C. S., Lee, M. H., Kim, C. K. & Kim, K. H. 90Sr, 137Cs, 239 + 240Pu and 238Pu concentrations in surface soils of Korea. J. Environ. Radioact. 40, 75–88 (1998).

Sha, L. M., Yamamoto, M. & Komura, K. 239, 240Pu, 241Am and 137Cs in soils from several areas in China. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. Letts. 155, 45–43 (1991).

Zheng, J., Yamada, M., Wu, F. C. & Liao, H. Q. Characterization of Pu concentration and its isotopic composition in soils of Gansu in northwestern China. J. Environ. Radioact. 100, 71–75 (2009).

Dong, W., Tims, S. G., Fifield, L. K. & Guo, Q. J. Concentration and characterization of plutonium in soils of Hubei in central China. J. Environ. Radioact. 101, 29–32 (2010).

Song, Y. X., Zhan, X. W. & Wang, Y. G. Modern sediment characteristic in north estuaries of the Liaodong Bay. Acta. Oceanol. Sin. 19, 145–149 (1997).

He, J. & Pan, S. M. 137Cs reference inventory and its distribution in soils along the Liaodong Bay. Chin. J. Soil Water Conserv. 25, 169–173 (2011).

Wu, F. C., Zheng, J., Liao, H. Q. & Yamada, M. Vertical distributions of plutonium and 137Cs in lacustrine sediments in northwestern China: quantifying sediment accumulation rates and source identifications. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 2911–2917 (2010).

Hodge, V., Smith, C. & Whiting, J. Radiocesium and plutonium: still together in “background” soils after more than thirty years. Chemosphere 32, 2067–2075 (1996).

ApSimon, H. M., Wilson, J. J. N. & Simms, K. L. Analysis of the dispersal and deposition of radionuclides from Chernobyl Across Europe. Proc. R. Soc. A 425, 365–405, 10.1098/rspa.1989.0111 (1989).

Levi, H. W. Radioactive deposition in Europe after the Chernobyl accident and its long-term consequences. Ecol. Res. 6, 201–216 (1991).

Daraoui, A. et al. Iodine-129, iodine-127 and caesium-137 in the environment: soil from Germany and Chile. J. Environ. Radioact. 112, 8–22 (2012).

Wu, F. C., Zheng, J., Liao, H. Q., Yamada, M. & Wan, G. J. Anomalous Plutonium Isotopic Ratios in Sediments of Lake Qinghai from the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 9188–9194 (2011).

Huh, C. A. & Su, C. C. Distribution of fallout radionuclides (7Be, 137Cs, 210Pb and 239,240Pu) in soils of Taiwan. J. Environ. Radioact. 77, 87–100 (2004).

Qiao, J. X., Hansen, V., Hou, X. L., Aldahan, A. & Possnert, G. Speciation analysis of 129I, 137Cs, 232Th, 238U, 239Pu and 240Pu in environmental soil and sediment. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 70, 1698–1708 (2012).

Li, N., Liu, Z. & Gu, W. Statistic analysis of average annual precipitation in the areas in and around Bohai Sea. Chinese Geogr. Res. 25, 1022–1030 (2006).

Sun, H. G. Sedimentary characteristics and environmental evolution in the North of Liaodong Bay since medium-term of late Pleistocene. Master thesis, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, China (2005).http://www.docin.com/p-563449844.html (open accessed on 11th Nov. 2013).

Qiao, J. X., Hou, X. L., Roos, P. & Miró, M. Rapid Determination of plutonium isotopes in environmental samples using sequential injection extraction chromatography and detection by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 81, 8185–8192 (2009).

Acknowledgements

Y.H.X. acknowledges the China Scholarship Council for financial support and Radioecology Programme (headed by Sven P. Nielsen), Center for Nuclear Technologies, Technical University of Denmark for supporting to her PhD study at DTU. The authors thank Andong Wang, Jian He, Rensong Pang, Xu Yang, Zuo Wang for their helps with sampling and map drawing. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41271289) and Innovation Method Fund China (2012IM030200).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M.P., X.L.H. and Y.H.X. designed the research plan. Y.H.X. and J.X.Q. conducted Pu isotopes analyses. Y.H.X. drafted the manuscript. X.L.H. and J.X.Q. revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Y., Qiao, J., Hou, X. et al. Plutonium in Soils from Northeast China and Its Potential Application for Evaluation of Soil Erosion. Sci Rep 3, 3506 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03506

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03506

This article is cited by

-

Ultra-Trace Analysis of Fallout Plutonium Isotopes in Soil: Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

Chemistry Africa (2023)

-

Effect of land use and vegetation coverage on level and distribution of plutonium isotopes in the northern Loess Plateau, China

Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry (2023)

-

First application of plutonium in soil erosion research on terraces

Nuclear Science and Techniques (2023)

-

Plutonium isotopes in the Qinling Mountains of China

Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry (2023)

-

Quantitative assessment of the spatial distribution of 239+240Pu inventory derived from global fallout in soils from Asia and Europe

Journal of Geographical Sciences (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.