Abstract

The authors report a case of intracranial epidural hemorrhage (ICEH) during spinal surgery. We could not find ICEH, though we recorded transcranial electrical stimulation motor evoked potentials (TcMEPs). A 35-year-old man was referred for left anterior thigh pain and low back pain that hindered sleep. Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging revealed an intradural tumor at L3–L4 vertebral level. We performed osteoplastic laminectomy and en bloc tumor resection. TcMEPs were intraoperatively recorded at the bilateral abductor digiti minimi (ADM), quadriceps, tibialis anterior and abductor hallucis. When we closed a surgical incision, we were able to record normal TcMEPs in all muscles. The patient did not fully wake up from the anesthesia. He had right-sided unilateral positive ankle clonus 15 min after surgery in spite of bilateral negative of ankle clonus preoperatively. Emergent brain computed tomography scans revealed left epidural hemorrhage. The hematoma was evacuated immediately via a partial craniotomy. There was no restriction of the patient’s daily activities 22 months postoperatively. We should pay attention to clinical signs such as headache and neurological findgings such as DTR and ankle clonus for patients with durotomy and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage. Spine surgeons should know that it was difficult to detect ICEH by monitoring with TcMEPs.

Similar content being viewed by others

The incidence of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) after spinal surgery is rare, whereas that of intracranial epidural hemorrhage (ICEH) is extremely rare.1,2 There are only five reported cases of ICEH after spinal surgery.2,3 Kaloostain et al. reported a 14% mortality rate in patients who had ICH after spinal surgery.4 Therefore, it is important to detect ICH after spinal surgery as quickly as possible. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports in the English literature evaluating intraoperative cauda eqina monitoring in patients who develop ICH after spinal surgery. In the present study, we describe early detection of ICEH after spinal surgery.

A 35-year-old man was referred for neurological evaluation with a 6-month complaint of low back pain that hindered sleep and left anterior thigh pain. No remarkable medical history was noted. His neurological examination was normal with no motor or sensory deficits. We suspected an intradural schwannoma at the L3–L4 vertebral level with magnetic resonance imaging.

We performed osteoplastic laminectomy and tumor resection. After releasing cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for local decompression, we identified the tumor within the arachnoid layer and removed it en bloc. The operation was completed uneventfully and we repaired the dura. The tumor was histopathologically identified as a schwannoma. The total operation time was 4 h and 6 min, intraoperative CSF loss was unknown, and blood loss was <200 ml. We performed cauda equina monitoring intraoperatively.

An electrophysiological monitoring system was used to record the transcranial electorical stimulation motor evoked potentials (TcMEPs). TcMEPs were recorded at the bilateral abductor digiti minimi (ADM), quadriceps, tibialis anterior and abductor hallucis.

We were able to record normal TcMEPs in all muscle when we closed the surgical incision (Figure 1).

Transcranial electrical stimulation motor evoked potentials (TcMEPs) were recorded from bilateral abductor digiti minimi (ADM), quadriceps, tibialis anterior (TA), and abductor hallucis (AH). Control wave forms were recorded at 11:34:27 (arrow head). Final wave forms at the end of the operation were recorded at 13:24:44 (arrow). The amplitude of the final TcMEPs was increased compared with that of the TcMEPs at the control wave form in all recorded muscles.

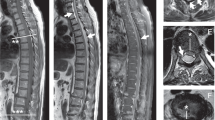

The patient did not fully wake up from the anesthesia. He had unilateral right-sided positive ankle clonus 15 min after surgery in spite of bilateral negative of ankle clonus preoperatively. We suspected ICH. The emergent brain computed tomography scans revealed left epidural hemorrhage (Figure 2). A left partial craniotomy was immediately performed and the hematoma was evacuated. The evacuated clot revealed a hematoma with no vascular pathology on histopathological examination. The ICEH was identified as a hemorrhage from the meningeal vein. There was no restriction of the patient’s daily activities 22 months postoperatively.

ICH is a rare complication after spinal surgery; cerebellar hemorrhage (CeH) is reportedly the most common and ICEH is reportedly the most uncommon complication.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 (Table 1) The etiology of remote ICH after spinal surgery remains unclear, but evidence suggests that it is caused by excessive CSF loss that results in cerebral dehydration, which causes stretching and eventually tearing of the bridging veins.4,7 However, there was three cases without durotomy and dural tear.4,7 We routinely perform cauda equina monitoring using TcMEPs in lumbar spinal surgery intraoperatively to detect early cauda equina injury. In this patient, we were not able to detect early ICH by monitoring with TcMEPs despite the large volume of hemorrhage. The consciousness of patients with ICH were not clear after surgery. Therefore, we were not able to precisely evaluate motor and sensory deficits. On the other hand, we could objectively evaluate the corticospinal tract function using the deep tendon reflex (DTR) and ankle clonus. In this patient, positive ankle clonus occurred before any TcMEPs abnormalities. Therefore, it is important to perform a thorough neurological exam and note the baseline DTR and ankle clonus in patients before they undergo surgery. It was difficult for this patient with ICH to detect a new neurological motor deficit by monitoring with TcMEPs. Transcranial electric stimulation mostly bypasses cortical synapses by directly activating subcortical motor axons.9 Transcranial electric stimulation activate the corticospinal tracts in the brainstem.10 Therefore, we could not detect a new neurological motor deficit by monitoring with TcMEPs.

ICH after spinal surgery is an extremely rare condition but should be considered a possible complication related to dural tears associated with this type of surgery. The review of remote CeH after supratentorial and spinal surgery reported that symptoms began within the first 10 h after surgery for 46% of patients and later than 10 h for 54%.11 ICH are related to intraoperative unintended durotomy and CSF leakage.12 Despite of the fact without durotomy and dural tear, there were three patients with ICH.4,7 But drain contained bloody CSF in all three cases. ICH can occur after any type of spinal surgery, in which CSF leakage has occurred during or after surgery. Therefore, we should keep ICH after spinal surgery in mind. We should pay attention to neurological findings such as DTR and ankle clonus after spinal surgery. Spine surgeons should know that it was difficult to detect ICEH by monitoring with TcMEPs.

References

Huang PH, Wu JC, Cheng H, Shih YH, Huang WC . Remote cerebellar hemorrhage after cervical spinal surgery. J Chin Med Assoc 2013; 76: 593–598.

Li ZJ, Sun P, Dou YH, Lan XL, Xu J, Zhang CY et al. Bilateral supratentorial epidural hematomas: a rare complication in adolescent spine surgery. –Case report-. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2012; 52: 646–648.

Grahovac G, Vilendecic M, Chudy D, Srdoc D, Skrlin J . Nightmare complication after lumbar disc surgery. Spine 2011; 36: E1761–E1764.

Kaloostian PE, Kim JE, Bydon A, Sciubra DM, Wolinsky JP, Gokaslan ZL et al. Intracranial hemorrhage after spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine 2013; 19: 370–380.

Ma X, Zhang Y, Wang T, Li G, Zhang G, Khan H et al. Acute intracranial hematoma formation following excision of a cervical subdural tumor: a report of two cases and literature review. Br J Neurosurgery 2014; 28: 125–130.

Surash S, Bhargava D, Tyagi A . Bilateral extradural hematoma formation following excision of a thoracic intradural lesion. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2009; 3: 137–140.

Khalabari MR, Khalabari I, Moharamzad Y . Intracranial hemorrhage following lumbar spine surgery. Eur Spine J 2012; 21: 2091–2096.

Hempelmann RG, Mater E . Remote intracranial parenchymal haematomas as complications of spinal surgery: presentation of three cases with minor or untypical symptoms. Eur Spine J 2012; 21: S564–S568.

MacDonald DB . Intraoperative motor evoked potential monitoring: overview and update. J Clin Monit Comput 2006; 20: 347–377.

Deletis V . Intraoperative neurophysiology and methodologies used to monitor the functional integrity of the motor system. In: Deletis V, Shils JL (eds). Neurophysiology in neurosurgery. Academic Press, California, USA, 2002, pp 25–51.

Brockmann MA, Groden C . Remote cerebellar hemorrhage: a review. Cerebellum 2006; 5: 64–68.

Ulivieri S, Meri L, Oliveri G . Remote cerebellar haematoma after lumbar disc surgery. Case report. Ann Ital Chir 2009; 80: 219–220.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Imajo, Y., Kanchiku, T., Suzuki, H. et al. Intracranial epidural hemorrhage during lumbar spinal surgery. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 2, 15040 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/scsandc.2015.40

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/scsandc.2015.40