Abstract

Objective:

Translation of the Spinal Cord Injury Falls Concern Scale (SCI-FCS); validation and investigation of psychometric properties.

Design:

Translation, adaptation and validation study.

Subjects/patients:

Eighty-seven wheelchair users with chronic SCI attending follow-up at Rehab Station Stockholm/Spinalis, Sweden.

Methods:

The SCI-FCS was translated to Swedish and culturally adapted according to guidelines. Construct validity was examined with the Mann–Whitney U-test, and psychometric properties with factor and Rasch analysis.

Results:

Participants generally reported low levels of concerns about falling. Participants with higher SCI-FCS scores also reported fear of falling, had been injured for a shorter time, reported symptoms of depression, anxiety and fatigue, and were unable to get up from the ground independently. Falls with or without injury the previous year, age, level of injury, sex and sitting balance did not differentiate the level of SCI-FCS score. The median SCI-FCS score was 21 (range 16–64). Cronbachs alpha (0.95), factor and Rasch analysis showed similar results of the Swedish as of the original version.

Conclusion:

The Swedish SCI-FCS showed high internal consistency and similar measurement properties and structure as the original version. It showed discriminant ability for fear of falling, time since injury, symptoms of depression or anxiety, fatigue and ability to get up from the ground but not for age, gender or falls. Persons with shorter time since injury, psychological concerns, fatigue and decreased mobility were more concerned about falling. In a clinical setting, the SCI-FCS might help identifying issues to address to reduce the concerns about falling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Falls research in wheelchair using people with spinal cord injury (SCI) is a relatively new field but indicates that falls are common.1, 2 Fear of falling (FOF) is closely connected to falls in people with neurological disease.3 It may lead to limitations in activity and restrictions in participation and might thus be an indication for interventions. FOF, or concerns about falling, is often measured in the ambulating population with the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I),4 a self-assessed questionnaire, which assesses the level of concerns about falling during daily activities. On the basis of the FES-I, Boswell-Ruys et al.5 developed the SCI Falls Concern Scale (SCI-FCS), assessing concern about falling in daily activities related to wheelchair users with SCI. It has shown good test-retest reliability, internal consistency and a strong relationship between SCI-FCS score and a single-item question on FOF.6

To enable the assessment of concerns about falling in a Swedish sample with chronic SCI, the aim of this study was to translate and cross-culturally adapt the SCI-FCS to Swedish and to evaluate its psychometric properties including construct validity and internal consistency, and to assess its structural validity.

Materials and Methods

Translation and adaptation

The translation of the English version was performed with respect to the Norwegian version (Måøy Å. Concerns of falling in individuals with SCI who depend on a wheelchair. [Master thesis]: Oslo: University of Oslo; 2014) and the Swedish FES-I.7

Two bilingual translators with Swedish as their mother tongue did the first translation independently (Figure 1). Their versions were synthesized into version 1 by an expert committee of four physiotherapists/researchers. Subsequently, comments from a multidisciplinary group with expertise in SCI (n=5), including people with SCI, assistant nurse, occupational therapist and physician were synthesized into version 2. Back-translation was performed independently by two bilingual translators with English as their mother tongue. Their versions were synthesized and culturally adapted by the expert committee into version 3. In item 12, pushing wheelchair on uneven surface (for example, rocky ground, irregular pavement), the examples were changed to gravel, cobblestones, icy and snowy ground. Version 3 was pre-tested and commented by three individuals (age 30–52 years, level of injury C7, T12 and L1, AIS A and B). Thereafter, the expert committee discussed and adjusted the semantics into version 4. This version was pilot-tested on 15 individuals (aged 26–66 years, level of injury C5-L3, AIS A–D) and confirmed as final.

Validation

This project is part of the SCI Prevention of Falls Study (SCIP Falls), an on-going prospective study of 220 subjects within Sweden and Norway. Participants were recruited when attending follow-up at Rehab Station Stockholm’s SCI unit/Spinalis in Stockholm, Sweden, between April 2013 and April 2014. All applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed.

Participants

Included were: individuals with traumatic SCI who used wheelchair for at least 75% of their mobility needs,5 age ⩾18 years, ⩾1 year post injury and with sufficient knowledge of Swedish. Individuals with motor complete injuries according to American Spinal Cord Injury Impairment Scale (AIS) above C5 and injuries below L5 were excluded. Eighty-seven individuals (65 males) with SCI, median age 49 years (range 18–79) and median 15 years (range 2–52) since injury were included (Table 1). Of the 108 eligible individuals, 3 did not turn up, 10 denied participation and 8 were excluded owing to acute need for clinical intervention.

Procedure and measures

The participants were asked about previous falls (defined as ‘an unexpected event in which the participants come to rest on the ground, floor, or lower level’ according to the Prevention of Falls Network Europe (ProFaNE))8 and fall-related injuries during the previous year. They were also asked whether they, in general, were afraid of falling (not at all, a little, quite a bit or very much),6 and about their ability to get up from the ground (no/yes). The interview included the International Spinal Cord Society data set of quality of life and the Secondary Conditions Scale.9 The Secondary Conditions Scale9 is a self-reported 16-item instrument, which assesses health and physical functioning after SCI using a 4-point ordinal scale where higher scores indicate greater problems.

SCI-specific classifications were performed according to AIS guidelines. The T-shirt test (time to put on/take off at T-shirt)10 was used to assess sitting balance, it was repeated twice and the average total time was used.

Participants rated their concerns about falling with the 16-item self-reported questionnaire SCI-FCS. It is a 4-point ordinal scale where higher scores indicate greater concerns, sum score 16–64. Symptoms of anxiety and depression were assessed on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale,11 a 14-item scale, scored 1–3, where 7 items relate to anxiety and 7 to depression. A score above 8 of 21 on either subscale has been considered as the cutoff point for indicating the symptoms of anxiety or depression.11 Fatigue was assessed on the 9-item Fatigue Severity Scale.12 Participants rate their degree of agreement on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), higher score equals more fatigue. The average score was calculated and a cutoff of ⩾4 was used to indicate fatigue.13

Data analysis

Similarly to Boswell-Ruys et al.,5 variables were dichotomized, by the absence or presence of FOF, falling less than or equal to one and more than once the previous year, inability or ability to get up from the ground unaided, below or above median age (49 years), absence or presence of voluntary motor function below T6 (reflecting abdominal muscle innervation), and less or more than median time since injury (15 years). Moreover, variables were dichotomized as the absence or presence of a fall-related injury during the previous year, below or above cutoff scores on Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and Fatigue Severity Scale, below or above median score on the Secondary Conditions Scale and T-shirt test. Missing data on SCI-FCS, Fatigue Severity Scale or Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale were replaced by the individual mean score according to the ProFaNE guidelines.14 The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to detect the differences between groups and P⩽0.05 was considered significant.

Factor analysis was performed to assess whether the underlying dimensions of concerns about falling were equivalent in the Swedish and English versions of the SCI-FCS. Principal component analysis with varimax rotation was used to determine the number of factors with an eigenvalue >1. The number of factors was confirmed by inspecting the scree plot, which plots eigenvalues against a factor number. An extraction using oblique rotation was then performed to assess the correlation between the factors, and a single-factor solution was specified to determine the unity of the scale. The Cronbach’s α for the total SCI-FCS was calculated to investigate internal reliability, and an α<0.90 was considered desirable for clinical purposes.15 IBM SPSS 22 (Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the analysis.

Rasch analysis was performed with the Winsteps version 3.81 (Beaverton, OR, USA) to explore the questionnaire structure and the unidimensionality of the SCI-FCS, and to determine the goodness of fit for items and persons according to the item response theory. The expected mean square is 1.00 and the expected value of z is zero.16 The mean square and standardized goodness-of-fit statistics (z) for the items were determined and the level for misfit was pre-set at mean square <1.4 with an associated z⩾2.0.16, 17The Andrich thresholds17 were used to differentiate the scale-steps (‘not concerned’, ‘somewhat concerned’, ‘fairly concerned’ and ‘very concerned’) from each other. Pre-set level of accepted thresholds were >1.4 and <5 logits according to guidelines.17 The item-person map was inspected to reveal the distribution of items and persons.17

Results

The median SCI-FCS score was 21 (range 16–64). The activities causing greatest concerns about falling were pushing wheelchair on uneven surface (item 12), up/down gutters or curbs (item 13) or up/down a slope (item 14) and lifting heavy objects (item 16) followed by transferring from wheelchair to toilet (item 5) or car (item 7). Thirteen participants (16%) scored the lowest possible (16/64), while only one scored the maximum (64/64).

Fifty-three percent answered ‘no’ to the question ‘are you afraid of falling?’ (Figure 2). Falls the previous year were reported by 70% while 35% reported fall-related injuries.

Individuals with shorter time since injury, who answered ‘yes’ to the question on FOF, reported higher values on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Fatigue Severity Scale or Secondary Conditions Scale and were unable to get up from the ground unaided reported a higher total score on the SCI-FCS (Table 2).

Factor analysis revealed three different factors (Table 3). The first, characterized by different transfer situations, explained 31% of the variance; the second, characterized by different situations when the participants were reaching for and handling objects explained further 28%; and the third, pushing wheelchair on different surfaces, explained further 15%. Cronbachs α was 0.954.

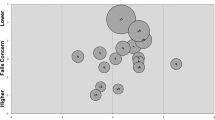

Rasch analysis revealed an explained variance of 57% (35% by persons, 22% by items). The unexplained variances in the first and second contrast were 8% and 7%, respectively. All items but 12 (infit mean square 1.72, Z standard deviation (z std) of 3.46), showed goodness of fit. Misfitting mean square and z std values were seen in 8% of the participants. The bubble chart (Figure 3) revealed misfitting values >2 logits17 on the standardized t-scale in item 8 (reaching for high objects) and 12 (pushing wheelchair on uneven surface). The Andrich thresholds were −1.82, 0.49 and 1.33 logits. The item-person map revealed that most items were gathered together in the middle with item 12 and 13 causing greatest concerns about falling and item 11 causing least.

Rasch bubble chart for the SCI-FCS as a graphical representation of measure and fit value. Bubbles are named after the items as presented in Table 3 and sized by their standard errors. Items assessing higher levels of concern about falling are at the top (positive logits) and items assessing low levels are at the bottom (negative logits). The horizontal axis shows the weighted t statistics (outfit standardized value ‘Zstd’) with a z std t value above ±2 representing misfitting items.

Discussion

Using the SCI-FCS in a Swedish sample revealed low levels of concerns about falling. Those who scored higher on the SCI-FCS had shorter time since injury and reported FOF, symptoms of depression and anxiety, fatigue, secondary conditions, and were unable to get up from the ground. Interestingly, the SCI-FCS could not discriminate between experience of falls (with or without injury), age and level of SCI. The factor and Rasch analysis revealed factors and patterns similar to the English version, supporting the structure of the scale. Internal consistency was desirable.

Similarly to Boswell-Ruys et al.,5 we found an association between the SCI-FCS total score and the question on FOF6 even though they represent two different fall-related psychological constructs, ‘concerns about falling’ and ‘fear of falling’.18

In the study by Boswell-Ruys et al.,5 where 40% had been injured less than a year ago, they found higher concerns, although not significant, in participants with acute SCI (<1 year), compared with chronic. Moreover, they found a higher median SCI-FCS score, 24, than in the present study, 21. In accordance with this, we found that fewer years since injury (<15 years) were related to a higher SCI-FCS score; indicating that concerns about falling might change over time.

People with SCI who experienced more anxiety and or depressive symptoms, fatigue or secondary complications showed greater concerns about falling. Those who experience more health-related problems in general might be more prone to concerns about falling. Reduced quality of life and depression have been shown to be associated with higher concerns about falling in elderly people.19 Reporting a lower level of fatigue and/or less secondary complications might also reflect better general health, which might interfere with physical function, such as ability to get up from the ground. An individual with lower health status might also be more concerned about falling because a fall might have more detrimental consequences. This ought to be considered in clinical settings.

As did Boswell-Ruys et al.,5 we found that those who were able to get up from the ground reported less concerns about falling. The consequence of a fall is probably more threatening if you are unable to get up, thus practicing transfers from the ground might reduce concerns about falling. In contradiction to Boswell-Ruys et al.,5 where participants with few falls reported less concern, we found no difference in the level of concerns about falling for those who reported falls or fall-related injuries. This might indicate that concerns about falling in people with SCI are not merely based on the experience of falls. Because most falls are not injurious, experiencing falls without injuries might reduce the concerns about falling. Some people reported that a fall now and then was a low price to pay for an active lifestyle. Living a physically active life, even for people using wheelchairs, might include a fall occasionally.

Age did not differentiate the level of concerns about falling, similar to the result of Boswell-Ruys et al.,5 and a study on people with multiple sclerosis in equivalent age.3 No gender difference was found in this study nor in the study by Boswell-Ruys et al.,5 although other studies in individuals with neurological diseases have found women to be more concerned about falling.3, 20

Our study revealed three underlying dimensions of concerns about falling similar to those in the original SCI-FCS,5 thus supporting the consistency of the scale structure after the translation. Cronbach’s α was 0.95 which indicates desirable internal reliability for clinical purposes15 and was similar to the English version.

The unidimensionality and goodness of fit were equivalent to the English version. Although misfitting items arguably weaken scale unidimensionality, removal of misfitting items is not necessarily appropriate as item 8 (reaching for high objects), and especially item 12 (pushing wheelchair on uneven surface), is important for independent living. Some items might be performed in various ways, for example, item 15 (shopping) and item 7 (transferring in/out of car). According to the pre-set levels, the Andrich threshold between the second and third, and between the third and fourth scale-step was too low, hence collapsing the scale-steps might be an alternative.17

This study has certain limitations; it was performed in a convenience sample and previous falls were retrospectively self-reported, which probably biased the numbers. There were in general very little missing data, (randomly distributed), aside from the T-shirt test,10 which 29 participants omitted owing to pain, risk of negative impact on ulcers or insufficient balance in sitting. We preferred the missing data before risking to worsening pain or ulcers; and we included participants with more severe injuries than intended for the test.

Conclusion

The Swedish version of the SCI-FCS retained similar structure as the English version, thus supporting the stability of the scale. SCI-FCS showed discriminant ability for fear of falling, time since injury, ability to get up from the ground, symptoms of depression or anxiety, fatigue and secondary conditions. However, it did not discriminate between age, gender or falls. Persons with shorter time since injury, psychological concerns, fatigue and decreased mobility were more concerned about falling. Generally, people with chronic SCI reported low levels of concerns about falling although falls were common. In the clinical setting, the SCI-FCS might be useful for screening what to address to reduce the concerns about falling.

Data Archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Nelson AL, Groer S, Palacios P, Mitchell D, Sabharwal S, Kirby RL et al. Wheelchair-related falls in veterans with spinal cord injury residing in the community: a prospective cohort study. Arch Physl Med Rehabil 2010; 91: 1166–1173.

Amatachaya S, Wannapakhe J, Arrayawichanon P, Siritarathiwat W, Wattanapun P . Functional abilities, incidences of complications and falls of patients with spinal cord injury 6 months after discharge. Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 520–524.

van Vliet R, Hoang P, Lord S, Gandevia S, Delbaere K . Falls efficacy scale-international: a cross-sectional validation in people with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013; 94: 883–889.

Yardley L, Beyer N, Hauer K, Kempen G, Piot-Ziegler C, Todd C . Development and initial validation of the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I). Age Ageing 2005; 34: 614–619.

Boswell-Ruys CL, Harvey LA, Delbaere K, Lord SR . A Falls Concern Scale for people with spinal cord injury (SCI-FCS). Spinal Cord 2010; 48: 704–709.

Yardley L, Smith H . A prospective study of the relationship between feared consequences of falling and avoidance of activity in community-living older people. Gerontologist 2002; 42: 17–23.

Nordell E, Andreasson M, Gall K, Thorngren K-G . Evaluating the Swedish version of the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I). Advances in Physiotherapy 2009; 11: 81–87.

Lamb SE, Jorstad-Stein EC, Hauer K, Becker C . Development of a common outcome data set for fall injury prevention trials: the Prevention of Falls Network Europe consensus. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53: 1618–1622.

Kalpakjian CZ, Scelza WM, Forchheimer MB, Toussaint LL . Preliminary reliability and validity of a Spinal Cord Injury Secondary Conditions Scale. J Spinal Cord Med 2007; 30: 131–139.

Chen C-L, Yeung K-T, Bih L-I, Wang C-H, Chen M-I, Chien J-C . The relationship between sitting stability and functional performance in patients with paraplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003; 84: 1276–1281.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP . The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983; 67: 361–370.

Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD . The fatigue severity scale: Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol 1989; 46: 1121–1123.

Lerdal A, Wahl A, Rustoen T, Hanestad BR, Moum T . Fatigue in the general population: a translation and test of the psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the fatigue severity scale. Scand J Public Health 2005; 33: 123–130.

Skelton DA, Todd CJ . Prevention of Falls Network Europe: a thematic network aimed at introducing good practice in effective falls prevention across Europe. Four years on. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 2007; 7: 273–278.

Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, Dekker J et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol 2007; 60: 34–42.

Tesio L . Measuring behaviours and perceptions: Rasch analysis as a tool for rehabilitation research. J Rehabil Med 2003; 35: 105–115.

Bond TG, Fox CM . Applying the Rasch Model: Fundamental Measurement in the Human Sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc: Mahwah, NJ, USA. 2001.

Kendrick D, Kumar A, Carpenter H, Zijlstra GA, Skelton DA, Cook JR et al. Exercise for reducing fear of falling in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 11: Cd009848.

Delbaere K, Close JC, Mikolaizak AS, Sachdev PS, Brodaty H, Lord SR . The Falls Efficacy Scale International (FES-I). A comprehensive longitudinal validation study. Age Ageing 2010; 39: 210–216.

Peterson EW, Cho CC, von Koch L, Finlayson ML . Injurious falls among middle aged and older adults with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008; 89: 1031–1037.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the patients who participated in the study, to Annelie Olausson for help with recruiting, to Vivien Jørgensen and Åsa Måøy for supporting with the translation process, and Erika Nilson, Carin Bergfeldt, Åke Norsten and Madeleine Stenius for comments on translation. Thanks to Rehab Station Stockholm/Spinalis for support. Thanks for financial support to Karolinska Institutet and the Doctoral school in health care sciences, Sunnaas Rehabilitations Hospital, The Swedish Association of persons with Neurological disabilities, the Spinalis Foundation and Praktikertjänst.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Butler Forslund, E., Roaldsen, K., Hultling, C. et al. Concerns about falling in wheelchair users with spinal cord injury—validation of the Swedish version of the spinal cord injury falls concern scale. Spinal Cord 54, 115–119 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.125

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.125

This article is cited by

-

Identifying priorities for balance interventions through a participatory co-design approach with end-users

BMC Neurology (2023)

-

Cross-cultural adaptation and measurement properties of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the spinal cord injury - Falls Concern Scale

Spinal Cord (2022)

-

Thai translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Spinal Cord Injury Falls Concern Scale (SCI-FCS)

Spinal Cord (2020)

-

Quality of life, concern of falling and satisfaction of the sit-ski aid in sit-skiers with spinal cord injury: observational study

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2020)

-

Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the “Spinal Cord Injury-Falls Concern Scale” in the Italian population

Spinal Cord (2018)