Abstract

Homelessness among people with mental illness is a prevalent and persisting problem. This Review examines the intersection between mental illness and homelessness in high-income countries, including prevalence rates and changes over time, the harmful effects of homelessness, and evidence-based health and housing interventions for homeless people with mental illness. Special populations and their support needs are also highlighted. Throughout this Review, policy and service implementation failures that have precipitated and perpetuated homelessness among people with mental illness are discussed, and policy and practice priorities critical to reducing homelessness and improving health outcomes in this population are proposed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Homelessness is an extreme form of material deprivation that occurs when people do not have permanent, safe and adequate accommodations. Although there is no consensus on the types of living situation that constitute homelessness, definitions often include temporarily residing in emergency accommodations (such as shelters), living on the streets, in cars or in buildings not intended for human habitation or staying temporarily with family and friends (that is, hidden homelessness)1,2. People experiencing homelessness are also overrepresented in hospitals and jails, making these institutions central to some experiences of homelessness3,4.

Homelessness in its various forms is an enduring social problem that is widespread in high-income countries. An estimated 2.1 million people experience homelessness every year across 36 member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)5. As shown in Table 1, homelessness estimates and trends vary considerably among high-income countries. However, comparisons between countries are challenging due to different methodological approaches and definitions of homelessness. Still, there are evident prevalence trends in some countries. In the USA, there was a very slight, gradual decline in daily homelessness rates from 647,258 in 2007 to 582,462 in 2022, before increasing to 653,104 in 2023, as measured by annual point-in-time counts6. Similarly, homelessness has stagnated or increased in many European countries during the past decade, with the notable exception of Finland, which has observed sizable decreases in the number of people experiencing homelessness over the past decade7,8. Other high-income countries have failed to monitor homelessness rates at the population level, or have done so very narrowly, yielding a lack of clarity about the extent of the problem and the effectiveness of the investments made to address it.

Homelessness is fundamentally a housing problem, with the limited availability of affordable housing being a foremost contributor to homelessness in communities9. However, other key structural- and individual-level factors can also affect rates of homelessness. For example, both unemployment and the quality of the social safety net, such as income support programs, have been tied to homelessness rates10,11,12. In addition, poor health, early childhood adversity and trauma, and involvement in the criminal justice system are associated with increased risk of homelessness12. Thus, populations experiencing marginalization, such as people with mental illness, that are disproportionately affected by these structural- and individual-level factors are at higher risk of homelessness. It is estimated that 76.2% of people experiencing homelessness have a current mental disorder13.

Given the persistence of homelessness in many jurisdictions and the prevalence of mental illness among people experiencing homelessness, this Review will discuss the intersection of mental illness and homelessness, and identify urgent priorities for action in high-income countries.

Mental illness and homelessness: emergence of an intractable problem

The intersection between mental illness and homelessness in many high-income countries is often described as having its modern origins in deinstitutionalization. Beginning in the 1960s, many psychiatric hospitals were closed in response to growing concerns about the poor quality of care in those facilities, emerging evidence on recovery in mental illness and advancements in psychotropic medications. The scale of the psychiatric hospital closures during deinstitutionalization transformed mental health systems. Of the 559,000 state psychiatric hospital beds that existed in the USA in 1955, over 400,000 had been closed by the early 1980s14. Similar reductions in psychiatric inpatient beds occurred in Canada (a 70.6% decline from 1965 to 1981)15 and in the UK (a 60.0% decrease from 1954 to 1990)16. As a result, many long-stay hospital patients with serious mental illness were discharged to community settings. This transformational shift corresponded with rising rates of homelessness among people with mental illness during these decades. This led to assumptions that an insufficient supply of appropriate housing and mental health support alternatives had resulted in increased rates of homelessness for this population17. Recent research has questioned the extent to which there was a causal relationship between deinstitutionalization and homelessness rates among people with mental illness, with evidence that this may have been confounded by other societal changes that occurred during subsequent decades18. Nevertheless, deinstitutionalization precipitated the transformation of mental health systems, marked by the limited availability of community services and funding in some regions—ill-enduring effects with which community mental health systems continue to grapple and that disproportionally affect people with mental illness who experience homelessness16,17.

Over the past half-century, other macro-level social policies, societal factors and systemic issues have been identified as yielding multiple pathways into homelessness for people with mental illness. This includes high rates of unemployment and precarious employment among people with mental illness, coupled with insufficient minimum wages and income support rates, as well as shortages in affordable and supportive housing, that make it challenging to find and keep housing19,20,21. Criminal record histories and substance use yield additional challenges to obtaining housing and employment22,23,24. At the systems level, fragmentation within and between health and social services can undermine efforts by homeless people with mental illness to achieve positive housing outcomes25. Furthermore, childhood family instability and lower educational attainment have been identified as early-life experiences that may affect homelessness risk and trajectories among people with mental illness22,24. Thus, the evolution of mental health service systems and inadequate social policies, potentially exacerbated by other forms of social exclusion, have contributed to homelessness among people with mental illness becoming an intractable problem.

Prevalence of mental illness among homeless populations

Similar to research on the rates of homelessness, studies examining the prevalence of mental illness, including substance use disorders, among homeless populations use different methodologies and samples. In addition, there has been a limited number of longitudinal studies on prevalence rates from the past decade. As a result, to understand emergent trends in prevalence, particularly with regard to problematic drug use among people experiencing homelessness, it is necessary to integrate research that examines epidemiology, treatment seeking and mortality rates. In this Review, comparisons of estimates are made only when there is sufficient methodological consistency between studies.

The rates of mental illness among people experiencing homelessness in high-income countries are high. As shown in Table 2, a recent meta-analysis of 39 publications from 1979 to 2019 indicated that between 64.0 and 86.6% of people experiencing homelessness have at least one diagnosable current mental disorder (defined as any Axis I disorder in the multiaxial system previously used by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders)13. Of the non-substance use disorder diagnostic categories examined in the meta-analysis, personality disorders were identified as the most prevalent (10.9–43.6%), followed by major depression (7.9–18.2%), schizophrenia spectrum disorders (9.5–15.7%) and bipolar disorders (2.0–6.7%). Compared to an earlier meta-analysis that comprised studies up to 2005, these prevalence rate estimates have been mostly stable26. Although post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was not examined in the aforementioned studies, its prevalence among people experiencing homelessness has been investigated in another recent meta-analysis. Findings showed that between 22.0 and 33.6% of people experiencing homelessness met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD, with significant heterogeneity in prevalence rates across high-income countries27. Similarly, a synthesis on intellectual disability among people experiencing homelessness found that prevalence estimates ranged from 12.0 to 38.9%, as determined via intellectual functioning assessments using intelligence quotient (IQ) estimates (IQ < 70 or IQ ≤ 70)28. However, there was considerable variation between and within samples, and adaptive functioning was not assessed, which may overestimate the prevalence of intellectual disability among homeless populations28. More broadly, meta-analyses have demonstrated high rates of ‘cognitive impairment’ within the population, with a pooled estimate of approximately 25% (ref. 29).

The prevalence of mental illness and addictions among homeless populations has changed over time. Early research involving three studies conducted in ten-year intervals using the same methods showed that the lifetime prevalence of non-substance use DSM Axis I disorders increased significantly for both men and women from 1980 to 200030. Major depression was the foremost contributor to the sharp increase in prevalence over the two decades, with rates of bipolar disorder and panic disorder also increasing to a lesser extent. By contrast, the prevalence of schizophrenia changed minimally. A more recent repeated longitudinal survey conducted every three years from 2000 to 2018 in the US state of Minnesota found increased rates of self-reported depression (from 24.3 to 44.3%), PTSD (from 13.1 to 35.6%), bipolar disorder (from 12.3 to 23.9%) and schizophrenia (from 6.4 to 10.9%) across the study period31. The prevalence rates in this study exceed the aforementioned meta-analysis estimates probably due to the use of unstandardized self-report tools, necessitating the need for interpretational caution. However, trend patterns over time may reflect changes in the types of disorder among people experiencing homelessness in the post-deinstitutionalization era. The rise was gradual for all disorders, with the exception of schizophrenia, which plateaued from 2006 onward. Thus, major mood disorders and the effects of trauma may be growing issues within homeless populations.

Substance use disorders are among the most prevalent mental disorders among homelessness populations. In the meta-analysis by Gutwinski and colleagues, prevalence estimates for alcohol use disorder and drug use disorder (excluding tobacco use disorder) ranged from 27.7 to 46.2% and from 13.1 to 31.7%, respectively13. However, tobacco is the most commonly used drug. A systematic review of smoking prevalence among adults experiencing homelessness ranged from 57.3 to 81.7% (ref. 32). Other types of drug commonly used by people experiencing homelessness include opioids, methamphetamine and cocaine. Drug use patterns and disorder rates have changed over time, and these trends are probably shaped by evolving supplies of street drugs and laws about the legality of the substances. With regard to opioids, a large cohort study of people experiencing homelessness in the US city of Boston found a more than 1,400% increase in the synthetic opioid mortality rate from 2013 to 201833. The same study also demonstrated that polysubstance overdose deaths involving opioids had surpassed opioid-only deaths, attributable to increases in concurrent use of opioids with cocaine, benzodiazepine and alcohol over the study period. Other research has demonstrated an increase in concurrent methamphetamine and opioid use in recent years. In a national retrospective US study of people accessing substance use treatment from 2013 to 2017, the rate of concurrent methamphetamine use among people with opioid use disorder also experiencing homelessness increased from 13.8 to 25.0% (ref. 34). Earlier research also supports changing rates of methamphetamine and amphetamine use. A serial cross-sectional study of homeless and marginally housed people in the US city of San Francisco found that methamphetamine use within the past 30 days had nearly quadrupled among those under 35 years of age from 1996 (8.8%) to 2003 (33.0%)35. As for cocaine use disorder, according to a recent systematic review, lifetime prevalence among homeless populations increased from a median estimate of 16% among studies published in the 1980s to 37% among studies from 1990 to 201236. Gambling disorder has also been found to be many times higher among people experiencing homelessness than in the general population, with past-year prevalence estimates ranging from 9.0 to 25.7% (ref. 37).

Premature mortality among homeless people with mental illness

Mortality rates among people experiencing homelessness are many times higher than in the general population—a finding that has been replicated in multiple high-income countries38,39. Unsheltered homelessness further exacerbates this mortality disparity40. Life-expectancy estimates differ between studies, as well as by age and gender, but people experiencing homelessness generally live 16–28 fewer years than same-aged peers in the general population41. The noted variations in mortality rates and life expectancies between high-income countries may be attributable to differences in health systems, including universal coverage and social issues (for example, violence and homicide rates)42.

The effects of mental illness on mortality rates among people experiencing homelessness have been insufficiently studied. A ten-year follow-up study found that homeless men with schizophrenia in Australia had a non-significantly lower standardized mortality ratio than those without schizophrenia, but were more likely to die by suicide at a significantly younger age43. In a smaller five-year follow-up study of homeless men in Sweden, there were no deaths among men with schizophrenia, whereas many of those who died had substance use problems44. Similarly, a national study conducted in Denmark found that schizophrenia spectrum disorders were a non-significant predictor of mortality among women experiencing sheltered homelessness, whereas men with schizophrenia spectrum disorders had a lower probability of dying than men without contact with the mental health system45. Earlier research has also found mental illness to be a non-significant predictor of mortality among people experiencing homelessness, with one study from 1999 reporting that men with mental illness had a lower likelihood of mortality over a seven-year period than men without mental illness38. As for suicide as a cause of death among homeless people with mental illness, high attempt rates have been found in additional research46.

Although the relationship between mental illness, homelessness and mortality requires further investigation, the effects of substance use disorders on mortality among people experiencing homelessness are more evident and alarming. Homeless people with substance use disorders are at increased risk of mortality45. However, this association was not replicated in a recent study of predictors of mortality among older adults experiencing homelessness47, suggesting that the risk may be greater among younger cohorts. The relationship between substance use disorders and mortality risk is probably partially attributable to drug overdose being one of the leading causes of death among people experiencing homelessness48. Moreover, overdose as a cause of death among homeless populations is worsening. In a Boston cohort study from 2003 to 2018, the drug overdose mortality rate increased 9.35% annually48. Accordingly, the overdose crisis is a grievous and worsening threat facing homeless populations in high-income countries.

Few studies have examined the role of physical health conditions on mortality among homeless people with mental illness. However, physical health problems are prevalent among this population. The risk of cardiovascular disease, a leading cause of death among homeless populations, has been found to be more than two times higher among homeless people with mental illness than the reference normal risk49. Rates of chronic diseases are also high, with hypertension, migraine, arthritis and asthma being among the most common, as are blood-borne pathogens, such as HIV and viral hepatitis50,51. The disease burden of these conditions among homeless people with mental illness is critical for interventions to consider and warrants further investigation.

Living at the margins

Homelessness can be experienced transitionally, episodically or chronically. Studies from North America have demonstrated that most people have brief episodes of homelessness that are a few in number (that is, transitional homelessness)52,53. Fewer people have repeated episodes of homelessness over a short period of time or longer shelter stays that last years (that is, episodic and chronic homelessness, respectively). Research on the relationship between mental illness and type of homelessness experienced has produced varying findings. In a study of shelter-use patterns in two US cities, people with mental illness were more likely to experience episodic or chronic homelessness and less likely to be transitionally homeless53. By contrast, a similar study in Denmark found high rates of mental illness across each type of homelessness, but this was marginally lower among the chronically homeless group10. Similar results emerged in recent Canadian research, with lower mental health functioning being associated with trajectories of higher housing stability54. The differing findings suggest that the broader social policy and system contexts may affect how people with mental illness experience homelessness and its associated harms.

In all of its forms, homelessness is a period of instability and social exclusion that can precipitate and exacerbate mental illness, yielding a bidirectional relationship between the two experiences55. There are several factors that impel deteriorations in mental health. First, people experiencing homelessness have ‘competing priorities’ among multiple unmet needs56. This can lead to needs that are less immediate than shelter, food and safety to go unaddressed, such as healthcare. One US study found than approximately 20% of people experiencing homelessness reported a past-year unmet need for mental health services57. Poor care quality, inadequate continuity, and stigma and discrimination are additional barriers to addressing mental health and addiction needs58,59,60. These impediments contribute to an overreliance on acute care services, such as emergency departments, that have limited effectiveness in addressing long-term health needs60,61.

Exposure to trauma, violence and victimization is another factor that can negatively affect mental health. Although such experiences are prevalent before people become unhoused, homelessness yields a heightened risk of victimization22,62. Estimates of recent violent victimization among homeless adults with serious mental illness found prevalence rates of 45.0 and 76.7% for the past month and two months, respectively63. Other forms of trauma, including pedestrian-strike, self-injurious and burn injuries, are also more common among homeless populations than those with housing64,65. Traumatic events during homelessness can be among the most debilitating problems experienced by people with mental illness and complicate their mental health recovery trajectories66.

Enforcement responses to homelessness by police, bylaw authorities, courts and other legal institutions can cause additional harms. Interactions between people experiencing homelessness and the police are common. In a study of over 500 homeless adults with mental illness in Toronto, Canada, 55.8% had interactions with the police in the past year67. Some interactions were deemed unnecessary, as shown by 12.6% receiving charges for acts of living, such as substance use in public, indecent acts, fouling in a street or solicitation. Similar results were found in a US study, with people experiencing homelessness reporting that policing aimed at restricting the overnight use of public spaces was more harassing than helpful68. Concerns about police contact can also lead people experiencing homelessness to seek more isolated and unsafe sleeping locations where the risk of violent victimization is greater69. Furthermore, displacement practices, such as ‘sweeps’ and ‘cleanups,’ have been used in some cities to remove people experiencing unsheltered homelessness from public spaces. This approach not only fails to address the basic needs of people who are displaced but may also undermine safety and increase drug-related morbidity and mortality. In a simulation study, continual displacement of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness who inject drugs contributed to an additional 15.6–24.4% of deaths over a ten-year period70.

Coping with the adversities of homelessness and mental illness takes different forms. Street-based survival strategies, such as intentional avoidance, hypervigilance and the establishment of outward appearances of strength, are a common adaptation to living in hostile and stressful environments71,72. Substance use is another frequently used coping strategy, yet it is one that carries heightened risk due to unregulated street-drug supplies, barriers to substance use treatment and limited access to places to safely use drugs. The role of social support in the context of homelessness is complex and varied. Although other individuals experiencing homelessness can be a source of community and belonging, there is the risk of victimization and the adoption of unhealthy behaviors, which is heightened among people with mental illness, especially women63,73,74. Trusted and compassionate service providers offer another valuable source of support75, although negative experiences using health, social and community services due to stigma and discrimination can be a barrier to the development of positive working relationships and a reason for service avoidance76. Overall, the coping mechanisms used by people experiencing homelessness are focused on immediate survival and may conflict with longer-term goals.

Interventions for improving housing and health outcomes

A range of interventions have been developed over the past four decades to address the housing and health needs of homeless people with mental illness. Several interventions, including Housing First, Assertive Community Treatment (ACT), Intensive Case Management (ICM) and Critical Time Intervention (CTI), have been extensively studied and are recognized as effective with this population. Common across all of these interventions is the provision of community-based types of support, on either an ongoing or a time-limited basis. These interventions can be differentiated from each other by their intensity of support, with ACT being most appropriate for those who have higher, ongoing needs, ICM being suitable for individuals with moderate, ongoing needs and CTI being used for those in need of time-limited support during service transitions. Housing First is unique from these other three interventions as it includes access to permanent housing in addition to different types of community support. These four interventions are described in more detail below, followed by promising practices that require further study.

Housing First is widely regarded as a best practice intervention for people experiencing chronic homelessness and mental illness. The intervention involves the provision of permanent housing in the form of a rental subsidy or an affordable housing unit, with accompanying community-based support such as ACT or ICM. Key tenets that guide the intervention include: no requirements for sobriety or medication adherence, the separation of housing and supports, service user choice and use of a harm-reduction and mental health recovery orientation. The robust evidence base for Housing First includes rigorous randomized trials from Canada and France, which demonstrate that the intervention is highly effective in improving housing stability77,78,79. Studies have increasingly involved longer follow-up periods, demonstrating that most people continue to experience housing stability after six years79. Multiple systematic reviews have also concluded that Housing First is effective in reducing emergency department visits and hospital admissions80,81. These service use reductions contribute to Housing First being a cost-effective intervention, especially for people with high support needs82. As for health and social outcomes, intervention effects have been less impactful80. However, greater program fidelity is linked to more positive outcomes, including adaptive functioning, underscoring the importance of adherence to the Housing First model83. Ongoing experiences of poverty among Housing First service users and the need for chronic health problems to be treated over a longer duration have been discussed as potential contributory factors to the limited improvements in health and social outcomes, despite favorable service experiences84. It would be prudent for future research to consider the effects of long-standing interpersonal and structural trauma among people living in Housing First programs, as well as the needs of those that may not be able to live independently in the community. Greater integration of intensive treatment for trauma may reduce behaviors that could cause housing loss.

In addition to its role in Housing First, ACT is a standalone evidence-based intervention used with homeless adults that experience serious mental illness. ACT, using multidisciplinary teams with small caseloads that offer intensive contact and 24-hour coverage, has been found to yield greater reductions in homelessness and improvements in psychiatric symptom severity compared with standard case management in randomized controlled trials85,86. Unsurprisingly, the effects of ACT alone on housing outcomes are smaller than those found in Housing First87. ACT is similarly associated with reductions in hospitalization and emergency department visits in randomized controlled trials, although the findings are not unequivocal86. The effects of the intervention on quality of life and income are more limited, with no known studies examining employment outcomes86. Fewer studies have examined service users’ care experiences with ACT, although there is evidence of higher satisfaction with this model than standard care88.

ICM is another standalone community mental health intervention that is commonly used with homeless people who experience mental illness. ICM involves the provision of community-based supports via a case manager who has small caseloads to facilitate weekly contact and coordinate care with other service providers. On its own, ICM yields small reductions in the number of days spent homeless compared with usual care86. These effects are smaller than those found in ACT, with a recent meta-analysis suggesting that a team-based support approach may yield better housing outcomes than the individualized approach of ICM87. Improvements in quality of life, substance use and access to income supports have been found with ICM, whereas the intervention’s effects on mental health, hospitalization and employment outcomes are more limited86.

CTI is a time-limited case management intervention to reduce the risk of homelessness and enhance the continuity of care during service transitions (for example, following hospital discharge or entry into housing programs from homelessness). As with ICM, CTI workers are responsible for service provision and coordination. Randomized trials have found that CTI cam improve housing and service use outcomes among homeless people with serious mental illness during transition periods86,89. One non-randomized pre–post cohort study also found improvements in mental health symptoms and substance use problems, as well as reductions in the number of days spent in institutions90. No changes in income were found among CTI recipients in a single randomized trial89.

A recent trend in intervention research with homeless people that experience mental illness has been the adaptation of Housing First and case management-type interventions to include new supports and implementation contexts. For example, supported employment has been integrated into Housing First, which increased the likelihood of service users obtaining competitive employment91. Multidisciplinary adaptations of CTI have been used successfully with homeless people who have unmet mental health needs following hospital discharge92. Moreover, financial incentives have been used to promote service engagement in a variety of settings, with promising but mixed effects93. Thus, there is a current and ongoing research focus on how to augment evidence-based interventions to more effectively improve service engagement, health and housing outcomes among homeless people with mental illness.

In addition to the evidenced-based interventions described above, there are promising approaches that warrant further research. Peer-navigation interventions involve support delivered by people with lived experience to address unmet health needs and improve access to services. Although such services exist in many forms, research on peer navigation targeted to individuals at the intersection of homelessness and mental illness is more limited. One randomized trial of peer navigation with Black homeless adults who experience serious mental illness found that the intervention had small to moderate effects on health status, mental health recovery and quality of life94. A harm-reduction-based peer-navigation intervention for homeless people with problematic substance use was also found to be acceptable and yielded promising findings in a feasibility study95. The use of peer navigation could be leveraged in future work with other groups experiencing multiple disadvantage, such as homeless migrants with mental illness who face additional barriers to accessing health and social services.

Income support interventions are another promising approach, albeit one with considerable variability in intervention components and practices. One approach is the use of larger cash transfers to overcome the financial barriers to exiting homelessness77. A recent randomized controlled trial in Canada examined the effects of a single unconditional cash transfer of CAD$7,500 (ranging from approximately US$5,652–5,788 at the time of distribution) on adults experiencing homelessness with non-severe mental health and addiction symptoms96. Findings showed that the intervention significantly reduced the number of days spent homeless and did not change spending on substances over the one-year study period, suggesting that the cash transfer may hasten exits from homelessness96. Although this approach has yet to be tested with homeless people who experience mental illness, it has the potential to address a key problem faced by this population: income support rates being insufficient to access affordable housing. Accordingly, income support interventions and other basic income schemes warrant further investigation.

Experiences and support needs of special populations

There are many groups, including women, youth, older adults, people of diverse sexual orientations and gender identities (LGBT+), people with substance use disorders, people with intellectual disabilities and racialized individuals and migrants, who have unique needs and support considerations as well as some shared vulnerabilities (see Table 3). Most notable are the relationship conflicts and terminations that become a pathway into homelessness, as well as high rates of trauma and victimization risk once homeless. Ongoing discrimination in the context of homelessness is another critical issue for some groups, such as LGBT+ community members and racialized and migrant groups. These homelessness pathways and experiences highlight the importance of creating service settings that are perceived as safe by these groups and involve the provision of holistic, person-centered and trauma-informed supports. Furthermore, they underscore the need for transformative social change to prevent homelessness caused by housing exclusion and structural racism.

Evidence gaps

In light of the evidence presented in this narrative review, several key avenues for future research are proposed, which include changes in psychiatric epidemiology among homelessness populations, stigma-reduction strategies in mainstream health and social services, approaches to enhancing service engagement and the standardized measurement of homelessness, as detailed below.

The transformation of community mental health systems following deinstitutionalization led to multi-decades growth in research on the intersection of homelessness and mental illness. However, the structural and systemic factors that determine homelessness and its sequelae have continued to evolve, and knowledge development has not kept pace. Evidence on changes over time in the prevalence rates of mental illness among homeless populations remains limited. In addition, there is continued ambiguity with regard to the effects of mental illness on premature mortality in the context of homelessness. As people with mental illness are at higher risk of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases than those without mental illness97, it is also critical to understand how homelessness may exacerbate associated health disparities and the extent to which service innovations effectively address them. With the advancement of research using administrative health data repositories and public health surveillance data, there are likely to be opportunities to sustainably address this evidence gap to enable health and social service systems to respond to changes at the population level in a more timely manner.

Another key evidence gap centers on approaches for improving the quality of care for people experiencing homelessness in mainstream health services. Experiences of stigma and discrimination by health professionals are commonly reported among homeless people with mental illness71,76. Although specialized health services for homeless and unstably housed populations have been developed to create more accessible and welcoming programs, the marginalization and stigmatization of homeless populations persists in mainstream health services. Moreover, specialized services are less likely to be available in smaller cities and rural communities, and most do not provide continuous care once housed. Accordingly, there is a need to develop and evaluate stigma-reduction approaches for facilitating humanizing healthcare experiences among homeless people with mental illness in mainstream settings.

The delivery of health services to homeless people with mental illness is fraught with challenges. Although some systemic and structural barriers require innovation at the policy level, other problems, including service engagement, can be potentially addressed via improvements to service delivery approaches, including among specialized services for this population. Key factors that shape service engagement among homeless people with mental illness include self-perceived need, support availability and relational factors75,76. Given this, simply expanding mental health services without attending to care philosophy and recovery orientation may not precipitate increased service engagement among those in need. Thus, further research is warranted on person-centered practices for enhancing health service engagement among homeless people with mental illness. Peer-led interventions and the integration of people with lived experience in outreach engagement teams could be beneficial for strengthening working relationships between service users and providers. Advancing the evidence base on intervention considerations for special populations, such as those outlined in Table 3, will also be beneficial for adapting service approaches to improve engagement and outcomes.

Lastly, long-standing variations in the definitions and measurement of homelessness have hindered comparisons in prevalence rates between regions and countries, and deeper understandings of experiences within homeless populations. On the latter, for example, as unsheltered homelessness is associated with greater health harms than sheltered homelessness, aggregating these forms of homelessness may obscure differences between them. Thus, there is a critical need for future research to consistently define and measure homelessness. Leveraging existing typologies of homelessness1,2 will yield stronger methodological parallels between studies. With more homelessness research using administrative health datasets, integrating typologies of homelessness into these data-collection systems will enable more nuanced examinations of differences within homeless populations in future research. Use of the Residential Time-Line Follow-Back inventory, a self-report housing history measure with strong psychometric properties, is also recommended for measuring housing outcomes, especially in clinical trials and longitudinal research with people experiencing homelessness98.

Practice and policy priorities

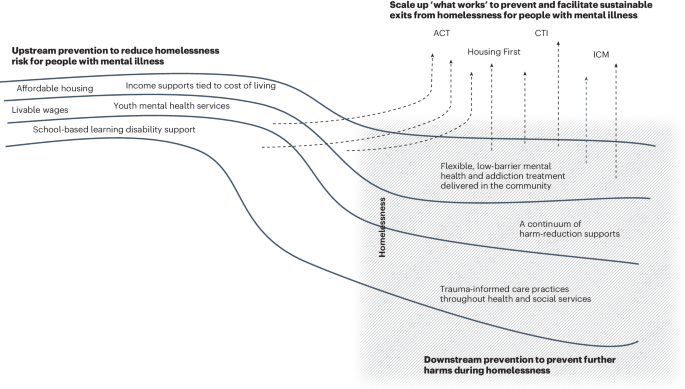

Effectively addressing the intractable problem of homelessness and mental illness requires investments that are comprehensive, multifaceted and evidence-based. Accordingly, we propose three practice and policy priorities that are critical for improving the health and wellness of homeless people with mental illness: (1) scale up ‘what works’, (2) strengthen upstream prevention and (3) establish needed downstream prevention supports (Fig. 1).

Improving the health and wellness of homeless people with mental illness requires more upstream prevention to reduce homelessness risk. Without this, people with mental illness are at greater risk of becoming homeless (as shown by the grey shaded box). Scaling up evidence-based interventions, such as Housing First, Assertive Community Treatment (ACT), Intensive Case Management (ICM), and Critical Time Intervention (CTI), is also key to preventing and facilitating exits from homelessness (as shown by the arrows that circumvent or direct away from homelessness). Downstream prevention are support services and orientations needed for preventing additional harms among people who are currently experiencing homelessness.

Scale up ‘what works’

Interventions such as Housing First, ACT, ICM and CTI are effective for improving housing and other outcomes among homeless people with mental illness. These interventions have been rigorously and extensively studied, demonstrating their generalizability to various homeless populations and service delivery contexts. Thus, there is a need to meaningfully scale up these evidence-based practices to meet the level of community need. The success of scale-up efforts is dependent on ensuring that services are sufficiently resourced to provide high-quality care with strong fidelity to program models. Too often, housing-focused interventions are implemented in real-world settings with a fraction of the resources used in research trials. Intermediary and purveyor organizations, which support the implementation and sustainability of evidence-based practices, can be leveraged to ensure that community mental health agencies have the tools to deliver high-quality services99. Although scaling up what works will require sizable resource investments, the achievement of cost offsets and superior outcomes would constitute fiscally smart spending.

Strengthen upstream prevention

Childhood adversity, pre-existing poverty, lower educational achievement and other forms of social exclusion are prevalent among homeless people with mental illness22,66, making upstream prevention a critical policy and intervention target. Investments to strengthen social safety nets, including more affordable housing, livable wages and income supports tied to the cost of living, will create a strong foundation for homelessness prevention among people with mental illness. Such upstream prevention efforts would align highly with an enhanced prioritization to scale up evidence-based interventions, such as Housing First, as demonstrated in Finland. Beginning in 2008, Finland undertook a highly successful national program to end chronic homelessness using a Housing First approach100. A key component of the program’s effectiveness was an emphasis on homelessness prevention through the development of social housing, which was targeted to young people100,101. Thus, Finland’s national program represents a concurrent investment in what works and upstream prevention, and holds great promise.

As the onset of many mental illnesses occurs by early adulthood, early intervention during childhood is another important upstream approach for preventing trajectories into homelessness. Reducing waiting lists for youth mental health and addiction treatment, and ensuring that these programs are integrated into community settings that serve at-risk groups are key to facilitating timely access to needed services. The detection of learning disabilities during childhood is another key preventive practice, given the overrepresentation of people with learning disabilities among homeless people with mental illness and their association with lower education attainment and poorer health outcomes102.

Establish needed downstream prevention supports

It is anticipated that prioritizing the other two policy and practice domains will reduce the need for downstream prevention supports, which should nonetheless remain a focus of intervention development and implementation. It is important to acknowledge and address the dire circumstances in which homeless people with mental illness are currently living and dying. Overdose fatalities and barriers to accessing mental health and addiction services are key problems that are currently faced by homeless populations and direct service providers33,59,103. Accordingly, there is an urgent need to increase the supply of person-centered, flexible, low-barrier mental health and addiction services, as well as harm-reduction supports for this population. Embedding trauma-informed practices throughout health and social services is instrumental for promoting service engagement and preventing further traumatization among this vulnerable population104.

Comprehensive policy and practice initiatives are needed to address the prevalent and persisting problem of homelessness among people with mental illness. Centering this work on upstream prevention and the scaling up of evidence-based practices, with concurrent, wraparound investments in accessible health and social services for homeless people with mental illness, will be best positioned to achieve sustainable, positive outcomes.

References

Gaetz, S. et al. Canadian Definition of Homelessness (Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press, 2012).

FEANTSA. ETHOS – European Typology on Homelessness and Housing Exclusion; https://www.feantsa.org/en/toolkit/2005/04/01/ethos-typology-on-homelessness-and-housing-exclusion (2017).

Greenberg, G. A. & Rosenheck, R. A. Jail incarceration, homelessness, and mental health: a national study. Psychiatr. Serv. 59, 170–177 (2008).

Lin, W. C., Bharel, M., Zhang, J., O’Connell, E. & Clark, R. E. Frequent emergency department visits and hospitalizations among homeless people with Medicaid: implications for Medicaid expansion. Am. J. Public Health 105, S716–S722 (2015).

HC3.1. Homeless population. OECD Affordable Housing Database https://www.oecd.org/els/family/HC3-1-Homeless-population.pdf (2021).

de Souza, T. et al. The 2023 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Part 1: Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness (US Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2023).

Fondation Abbé Pierre and FEANTSA. Fifth Overview of Housing Exclusion in Europe; https://www.feantsa.org/en/news/2020/07/23/fifth-overview-of-housing-exclusion-in-europe-2020 (2020).

The Housing Finance and Development Centre of Finland. Homelessness in Finland 2022; https://www.ara.fi/en-US/Materials/Homelessness_reports/Homelessness_in_Finland_2022(65349) (2023).

Hanratty, M. Do local economic conditions affect homelessness? Impact of area housing market factors, unemployment, and poverty on community homeless rates. Hous. Policy Debate 27, 640–655 (2017).

Benjaminsen, L. & Andrade, S. B. Testing a typology of homelessness across welfare regimes: shelter use in Denmark and the USA. Hous. Stud. 30, 858–876 (2015).

Giano, Z. et al. Forty years of research on predictors of homelessness. Community Ment. Health J. 56, 692–709 (2020).

Nilsson, S. F., Nordentoft, M. & Hjorthøj, C. Individual-level predictors for becoming homeless and exiting homelessness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Urban Health 96, 741–750 (2019).

Gutwinski, S., Schreiter, S., Deutscher, K. & Fazel, S. The prevalence of mental disorders among homeless people in high-income countries: an updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLoS Med. 18, e1003750 (2021).

Lamb, H. R. Deinstitutionalization and the homeless mentally ill. Hosp. Community Psychiatry 35, 899–907 (1984).

Sealy, P. & Whitehead, P. C. Forty years of deinstitutionalization of psychiatric services in Canada: an empirical assessment. Can. J. Psychiatry 49, 249–257 (2004).

Craig, T. & Timms, P. W. Out of the wards and onto the streets? Deinstitutionalization and homelessness in Britain. J. Ment. Health 1, 265–275 (1992).

Sylvestre, J., Nelson, G. & Aubry, T. (eds) Housing, Citizenship, and Communities for People with Serious Mental Illness: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy Perspectives (Oxford Univ. Press, 2017).

Winkler, P. et al. Deinstitutionalised patients, homelessness and imprisonment: systematic review. Br. J. Psychiatry 208, 421–428 (2016).

Forchuk, C. et al. Housing, income support and mental health: points of disconnection. Health Res. Policy Sys. 5, 14 (2007).

Padgett, D. K. Homelessness, housing instability and mental health: making the connections. BJPsych Bull. 44, 197–201 (2020).

Piat, M. et al. Pathways into homelessness: understanding how both individual and structural factors contribute to and sustain homelessness in Canada. Urban Stud. 52, 2366–2382 (2015).

Fitzpatrick, S., Bramley, G. & Johnsen, S. Pathways into multiple exclusion homelessness in seven UK cities. Urban Stud. 50, 148–168 (2013).

Poremski, D., Whitley, R. & Latimer, E. Barriers to obtaining employment for people with severe mental illness experiencing homelessness. J. Ment. Health 23, 181–185 (2014).

Sullivan, G., Burnam, A. & Koegel, P. Pathways to homelessness among the mentally ill. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 35, 444–450 (2000).

Rosenheck, R. et al. Service system integration, access to services, and housing outcomes in a program for homeless persons with severe mental illness. Am. J. Public Health 88, 1610–1615 (1998).

Fazel, S., Khosla, V., Doll, H. & Geddes, J. The prevalence of mental disorders among the homeless in Western countries: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLoS Med. 5, e225 (2008).

Ayano, G., Solomon, M., Tsegay, L., Yohannes, K. & Abraha, M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among homeless people. Psychiatr. Q. 91, 949–963 (2020).

Durbin, A. et al. Intellectual disability and homelessness: a synthesis of the literature and discussion of how supportive housing can support wellness for people with intellectual disability. Curr. Dev. Disord. Rep. 5, 125–131 (2018).

Depp, C. A., Vella, L., Orff, H. J. & Twamley, E. W. A quantitative review of cognitive functioning in homeless adults. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 203, 126–131 (2015).

North, C. S., Eyrich, K. M., Pollio, D. E. & Spitznagel, E. L. Are rates of psychiatric disorders in the homeless population changing? Am. J. Public Health 94, 103–108 (2004).

Vickery, K. D. et al. Trends in trimorbidity among adults experiencing homelessness in Minnesota, 2000–2018. Med. Care 59, S220–S227 (2021).

Soar, K., Dawkins, L., Robson, D. & Cox, S. Smoking amongst adults experiencing homelessness: a systematic review of prevalence rates, interventions and the barriers and facilitators to quitting and staying quit. J. Smok. Cessat. 15, 94–108 (2020).

Fine, D. R. et al. Drug overdose mortality among people experiencing homelessness, 2003 to 2018. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2142676 (2022).

Han, B. H., Doran, K. M. & Krawczyk, N. National trends in substance use treatment admissions for opioid use disorder among adults experiencing homelessness. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 132, 108504 (2022).

Das-Douglas, M., Colfax, G., Moss, A. R., Bangsberg, D. R. & Hahn, J. A. Tripling of methamphetamine/amphetamine use among homeless and marginally housed persons, 1996–2003. J. Urban Health 85, 239–249 (2008).

Perez, G. R., Ustyol, A., Mills, K. J., Raitt, J. M. & North, C. S. The prevalence of cocaine use in homeless populations: a systematic review. Curr. Treat. Options Psychiatry 9, 246–279 (2022).

Deutscher, K. et al. The prevalence of problem gambling and gambling disorder among homeless people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gambl. Stud. 39, 467–482 (2023).

Barrow, S. M., Herman, D. B., Córdova, P. & Struening, E. L. Mortality among homeless shelter residents in New York City. Am. J. Public Health 89, 529–534 (1999).

Seastres, R. J. et al. Long‐term effects of homelessness on mortality: a 15‐year Australian cohort study. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 44, 476–481 (2020).

Roncarati, J. S. et al. Mortality among unsheltered homeless adults in Boston, Massachusetts, 2000–2009. JAMA Intern. Med. 178, 1242–1248 (2018).

Romaszko, J., Cymes, I., Dragańska, E., Kuchta, R. & Glińska-Lewczuk, K. Mortality among the homeless: causes and meteorological relationships. PLoS ONE 12, e0189938 (2017).

Liu, M. & Hwang, S. W. Health care for homeless people. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 7, 5 (2021).

Babidge, N. C., Buhrich, N. & Butler, T. Mortality among homeless people with schizophrenia in Sydney, Australia: a 10-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 103, 105–110 (2001).

Beijer, U., Andréasson, A., Agren, G. & Fugelstad, A. Mortality, mental disorders and addiction: a 5-year follow-up of 82 homeless men in Stockholm. Nord. J. Psychiatry 61, 363–368 (2007).

Nielsen, S. F., Hjorthøj, C. R., Erlangsen, A. & Nordentoft, M. Psychiatric disorders and mortality among people in homeless shelters in Denmark: a nationwide register-based cohort study. Lancet 377, 2205–2214 (2011).

Prigerson, H. G., Desai, R. A., Liu-Mares, W. & Rosenheck, R. A. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in homeless mentally ill persons: age-specific risks of substance abuse. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 38, 213–219 (2003).

Brown, R. T. et al. Factors associated with mortality among homeless older adults in California: the HOPE HOME study. JAMA Intern. Med. 182, 1052–1060 (2022).

Dickins, K. A. et al. Mortality trends among adults experiencing homelessness in Boston, Massachusetts from 2003 to 2018. JAMA Intern. Med. 183, 488–490 (2023).

Gozdzik, A., Salehi, R., O’Campo, P., Stergiopoulos, V. & Hwang, S. W. Cardiovascular risk factors and 30-year cardiovascular risk in homeless adults with mental illness. BMC Public Health 15, 165 (2015).

Mejia-Lancheros, C. et al. Dental problems and chronic diseases in mentally ill homeless adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 20, 419 (2020).

Klinkenberg, W. D. et al. Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C among homeless persons with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Compr. Psychiatry 44, 293–302 (2003).

Aubry, T., Farrell, S., Hwang, S. W. & Calhoun, M. Identifying the patterns of emergency shelter stays of single individuals in Canadian cities of different sizes. Hous. Stud. 28, 910–927 (2013).

Kuhn, R. & Culhane, D. P. Applying cluster analysis to test a typology of homelessness by pattern of shelter utilization: results from the analysis of administrative data. Am. J. Community Psychol. 26, 207–232 (1998).

Aubry, T. et al. Housing trajectories, risk factors, and resources among individuals who are homeless or precariously housed. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 693, 102–122 (2021).

Nilsson, S. F. et al. The bidirectional association between psychiatric disorders and sheltered homelessness. Psychol. Med. 8, 1–11 (2023).

Gelberg, L., Gallagher, T. C., Andersen, R. M. & Koegel, P. Competing priorities as a barrier to medical care among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Am. J. Public Health 87, 217–220 (1997).

Baggett, T. P., O’Connell, J. J., Singer, D. E. & Rigotti, N. A. The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: a national study. Am. J. Public Health 100, 1326–1333 (2010).

Kerman, N. & Sylvestre, J. Surviving versus living life: capabilities and service user among adults with mental health problems and histories of homelessness. Health Soc. Care Community 28, 414–422 (2021).

Lamanna, D. et al. Promoting continuity of care for homeless adults with unmet health needs: the role of brief interventions. Health Soc. Care Community 26, 56–64 (2018).

Skosireva, A. et al. Different faces of discrimination: perceived discrimination among homeless adults with mental illness in healthcare settings. BMC Health Serv. Res. 14, 376 (2014).

Folsom, D. P. et al. Prevalence and risk factors for homelessness and utilization of mental health services among 10,340 patients with serious mental illness in a large public health mental system. Am. J. Psychiatry 162, 370–376 (2005).

Ellsworth, J. T. Street crime victimization among homeless adults: a review of the literature. Vict. Offender. 14, 96–118 (2019).

Roy, L., Crocker, A. G., Nicholls, T. L., Latimer, E. A. & Ayllon, A. R. Criminal behavior and victimization among homeless individuals with severe mental illness: a systematic review. Psychiatr. Serv. 65, 739–750 (2014).

Silver, C. M. et al. Injury patterns and hospital admission after trauma among people experiencing homelessness. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2320862 (2023).

Vrouwe, S. Q. et al. The homelessness crisis and burn injuries: a cohort study. J. Burn Care Res. 41, 820–827 (2020).

Padgett, D. K., Tiderington, E., Smith, B. T., Derejko, K.-S. & Henwood, B. F. Complex recovery: understanding the lives of formerly homeless adults with complex needs. J. Soc. Distress Homeless. 25, 60–70 (2016).

Kouyoumdjian, F. G. et al. Interactions between police and persons who experience homelessness and mental illness in Toronto, Canada: findings from a prospective study. Can. J. Psychiatry 64, 718–725 (2019).

Robinson, T. No right to rest: police enforcement patterns and quality of life consequences of the criminalization of homelessness. Urban Aff. Rev. 55, 41–73 (2019).

Westbrook, M. & Robinson, T. Unhealthy by design: health & safety consequences of the criminalization of homelessness. J. Soc. Distress Homeless. 30, 107–115 (2021).

Barocas, J. A. et al. Population-level health effects of involuntary displacement of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness who inject drugs in US cities. JAMA 329, 1478–1486 (2023).

Karadzhov, D., Yuan, Y. & Bond, L. Coping amidst an assemblage of disadvantage: a qualitative metasynthesis of first-person accounts of managing severe mental illness while homeless. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 27, 4–24 (2020).

Paul, S., Corneau, S., Boozary, T. & Stergiopoulos, V. Coping and resilience among ethnoracial individuals experiencing homelessness and mental illness. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 64, 189–197 (2018).

Duke, A. & Searby, A. Mental ill health in homeless women: a review. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 40, 605–612 (2019).

Phipps, M., Dalton, L., Maxwell, H. & Cleary, M. Women and homelessness, a complex multidimensional issue: findings from a scoping review. J. Soc. Distress Homeless. 28, 1–13 (2019).

Cummings, C., Lei, Q., Hochberg, L., Hones, V. & Brown, M. Social support and networks among people experiencing chronic homelessness: a systematic review. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 92, 349–363 (2022).

Kerman, N., Gran-Ruaz, S., Lawrence, M. & Sylvestre, J. Perceptions of service use among currently and formerly homeless adults with mental health problems. Community Ment. Health J. 55, 777–783 (2019).

Aubry, T. et al. Effectiveness of permanent supportive housing and income assistance interventions for homeless individuals in high-income countries: a systematic review. Lancet Public Health 5, e342–e360 (2020).

Loubière, S. et al. Housing First for homeless people with severe mental illness: extended 4-year follow-up and analysis of recovery and housing stability from the randomized Un Chez Soi d’Abord trial. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 31, e14 (2022).

Stergiopoulos, V. et al. Long-term effects of rent supplements and mental health support services on housing and health outcomes of homeless adults with mental illness: extension study of the At Home/Chez Soi randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 6, 915–925 (2019).

Baxter, A. J., Tweed, E. J., Katikireddi, S. V. & Thomson, H. Effects of Housing First approaches on health and well-being of adults who are homeless or at risk of homelessness: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 73, 379–387 (2019).

Peng, Y. et al. Permanent supportive housing with Housing First to reduce homelessness and promote health among homeless populations with disability: a community guide systematic review. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 26, 404–411 (2020).

Latimer, E. A. et al. Cost-effectiveness of Housing First with Assertive Community Treatment: results from the Canadian At Home/Chez Soi trial. Psychiatr. Serv. 71, 1020–1030 (2020).

Goering, P. et al. Further validation of the Pathways Housing First fidelity scale. Psychiatr. Serv. 67, 111–114 (2016).

Nelson, G. et al. Life changes among homeless persons with mental illness: a longitudinal study of Housing First and usual treatment. Psychiatr. Serv. 66, 592–597 (2015).

Coldwell, C. M. & Bender, W. S. The effectiveness of Assertive Community Treatment for homeless populations with severe mental illness: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 164, 393–399 (2007).

Ponka, D. et al. The effectiveness of case management interventions for the homeless, vulnerably housed and persons with lived experience: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 15, e0230896 (2020).

Weightman, A. L. et al. Exploring the effect of case management in homelessness per components: a systematic review of effectiveness and implementation, with meta-analysis and thematic synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 19, e1329 (2023).

Morse, G. A. et al. Treating homeless clients with severe mental illness and substance use disorders: costs and outcomes. Community Ment. Health J. 42, 377–404 (2006).

Jones, K. et al. Cost-effectiveness of Critical Time Intervention to reduce homelessness among persons with mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 54, 884–890 (2003).

Kasprow, W. J. & Rosenheck, R. A. Outcomes of Critical Time Intervention case management of homeless veterans after psychiatric hospitalization. Psychiatr. Serv. 58, 929–935 (2007).

Poremski, D., Rabouin, D. & Latimer, E. A randomised controlled trial of evidence based supported employment for people who have recently been homeless and have a mental illness. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 44, 217–224 (2017).

Stergiopoulos, V. et al. Bridging hospital and community care for homeless adults with mental health needs: outcomes of a brief interdisciplinary intervention. Can. J. Psychiatry 63, 774–784 (2018).

Hollenberg, E. et al. Using financial incentives to improve health service engagement and outcomes of adults experiencing homelessness: a scoping review of the literature. Health Soc. Care Community 30, e3406–e3434 (2022).

Corrigan, P. et al. Using peer navigators to address the integrated health care needs of homeless African Americans with serious mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 68, 264–270 (2017).

Parkes, T. et al. A peer-delivered intervention to reduce harm and improve the well-being of homeless people with problem substance use: the SHARPS feasibility mixed-methods study. Health Technol. Assess. 26, 1–128 (2022).

Dwyer, R., Palepu, A., Williams, C., Daly-Grafstein, D. & Zhao, J. Unconditional cash transfers reduce homelessness. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2222103120 (2023).

Firth, J. et al. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: a blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry 6, 675–712 (2019).

Tsemberis, S., McHugo, G., Williams, V., Hanrahan, P. & Stefancic, A. Measuring homelessness and residential stability: the residential time-line follow-back inventory. J. Community Psychol. 35, 29–42 (2007).

Dixon, L. B. & Patel, S. R. The application of implementation science to community mental health. World Psychiatry 19, 173–174 (2020).

Kaakinen, J. & Turunen, S. Finnish but not yet finished – successes and challenges of Housing First in Finland. Eur. J. Homeless. 15, 81–84 (2021).

Pleace, N., Baptista, I. & Knutagård, M. Housing First in Europe: An Overview of Implementation, Strategy and Fidelity (Housing First Europe Hub, 2019).

Patterson, M. L., Moniruzzaman, A., Frankish, C. J. & Somers, J. M. Missed opportunities: childhood learning disabilities as early indicators of risk among homeless adults with mental illness in Vancouver, British Columbia. BMJ Open 2, e001586 (2012).

Kerman, N., Ecker, J., Tiderington, E., Gaetz, S. & Kidd, S. A. Workplace trauma and chronic stressor exposure among direct service providers working with people experiencing homelessness. J. Ment. Health 32, 424–433 (2023).

Barry, A. R. et al. Trauma-informed interactions within a trauma-informed homeless service provider: staff and client perspectives. J. Community Psychol. 52, 415–434 (2024).

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Estimating Homelessness: Census; https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/housing/estimating-homelessness-census/latest-release (2023).

Fondation Abbé Pierre and FEANTSA. Eighth Overview of Housing Exclusion in Europe; https://www.feantsa.org/en/event/2023/09/05/?bcParent=27 (2023).

Gaetz, S., Gulliver, T. & Richter, T. The State of Homelessness in Canada: 2014 (The Homeless Hub Press, 2014).

Government of Canada. Everyone Counts 2020–2022: Preliminary Highlights report; https://www.infrastructure.gc.ca/homelessness-sans-abri/reports-rapports/pit-counts-dp-2020-2022-highlights-eng.html (2023).

Amore, K., Viggers, H. & Howden-Chapman, P. H. Severe Housing Deprivation in Aotearoa New Zealand, 2018: June 2021 Update (Te Tūāpapa Kura Kāinga – Ministry of Housing and Urban Development, 2021).

Halseth, L., Larsson, T. & Urstad, H. in Homeless in Europe: National Strategies for Fighting Homelessness 20–26 (FEANTSA, 2022).

Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., Merikangas, K. R. & Walters, E. E. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62, 617–627 (2005).

Kessler, R. C. et al. The prevalence and correlates of nonaffective psychosis in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Biol. Psychiatry 58, 668–676 (2005).

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edn (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Lenzenweger, M. F., Lane, M. C., Loranger, A. W. & Kessler, R. C. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol. Psychiatry 62, 553–564 (2007).

Grant, B. F. et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III. JAMA Psychiatry 73, 39–47 (2016).

Andermann, A. et al. Evidence-informed interventions and best practices for supporting women experiencing or at risk of homelessness: a scoping review with gender and equity analysis. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 41, 1–13 (2021).

Milaney, K., Williams, N., Lockerbie, S. L., Dutton, D. J. & Hyshka, E. Recognizing and responding to women experiencing homelessness with gendered and trauma-informed care. BMC Public Health 20, 397 (2020).

Schwan, K. et al. The State of Women’s Housing Need & Homelessness in Canada: A Literature Review (Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press, 2020).

Speirs, V., Johnson, M. & Jirojwong, S. A systematic review of interventions for homeless women. J. Clin. Nurs. 22, 1080–1093 (2013).

Davies, B. R. & Allen, N. B. Trauma and homelessness in youth: psychopathology and intervention. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 54, 17–28 (2017).

Edidin, J. P., Ganim, Z., Hunter, S. J. & Karnik, N. S. The mental and physical health of homeless youth: a literature review. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 43, 354–375 (2012).

Winiarski, D. A., Glover, A. C., Bounds, D. T. & Karnik, N. S. Addressing intersecting social and mental health needs among transition-age homeless youths: a review of the literature. Psychiatr. Serv. 72, 317–324 (2021).

Kozloff, N. et al. The unique needs of homeless youths with mental illness: baseline findings from a Housing First trial. Psychiatr. Serv. 67, 1083–1090 (2016).

Kidd, S. A. et al. The second national Canadian homeless youth survey: mental health and addiction findings. Can. J. Psychiatry 66, 897–905 (2021).

Brown, R. T., Thomas, M. L., Cutler, D. F. & Hinderlie, M. Meeting the housing and care needs of older homeless adults: a permanent supportive housing program targeting homeless elders. Seniors Hous. Care J. 21, 126–135 (2013).

Grenier, A. et al. A literature review of homelessness and aging: suggestions for a policy and practice-relevant research agenda. Can. J. Aging 35, 28–41 (2016).

Stergiopoulos, V. & Herrmann, N. Old and homeless: a review and survey of older adults who use shelters in an urban setting. Can. J. Psychiatry 48, 374–380 (2003).

Canham, S. L., Custodio, K., Mauboules, C., Good, C. & Bosma, H. Health and psychosocial needs of older adults who are experiencing homelessness following hospital discharge. Gerontologist 60, 715–724 (2020).

Humphries, J. & Canham, S. L. Conceptualizing the shelter and housing needs and solutions of older people experiencing homelessness. Hous. Stud. 36, 157–179 (2021).

Canham, S., Humphries, J., Moore, P., Burns, V. & Mahmood, A. Shelter/housing options, supports and interventions for older people experiencing homelessness. Ageing Soc. 42, 2615–2641 (2022).

Johnson, G. & Chamberlain, C. Homelessness and substance abuse: which comes first? Aust. Soc. Work 61, 342–356 (2006).

Schütz, C. G. Homelessness and addiction: causes, consequences and interventions. Curr. Treat. Options Psychiatry 3, 303–313 (2016).

Schütz, C. et al. Living with dual diagnosis and homelessness: marginalized within a marginalized group. J. Dual Diagn. 15, 88–94 (2019).

Bauer, L. K., Brody, J. K., León, C. & Baggett, T. P. Characteristics of homeless adults who died of drug overdoses: a retrospective record review. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 27, 846–859 (2016).

Riggs, K. R. et al. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with nonfatal overdose among veterans who have experienced homelessness. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e201190 (2020).

Miler, J. A. et al. What treatment and services are effective for people who are homeless and use drugs? A systematic ‘review of reviews’. PLoS ONE 16, e0254729 (2021).

Brown, M. & McCann, E. Homelessness and people with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review of the international research evidence. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 34, 390–401 (2021).

Lougheed, D. C. & Farrell, S. The challenge of a ‘triple diagnosis’: identifying and serving homeless Canadian adults with a dual diagnosis. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 10, 230–235 (2013).

Abramovich, A. Preventing, reducing and ending LGBTQ2S youth homelessness: the need for targeted strategies. Soc. Incl. 4, 86–96 (2016).

Ecker, J., Aubry, T. & Sylvestre, J. A review of the literature on LGBTQ adults who experience homelessness. J. Homosex. 66, 297–323 (2019).

Spicer, S. S. Healthcare needs of the transgender homeless population. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 14, 320–339 (2010).

Abramovich, I. A. No safe place to go – LGBTQ youth homelessness in Canada: reviewing the literature. Can. J. Fam. Youth 4, 29–51 (2012).

Maccio, E. M. & Ferguson, K. M. Services to LGBTQ runaway and homeless youth: gaps and recommendations. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 63, 47–57 (2016).

Fowle, M. Z. Racialized homelessness: a review of historical and contemporary causes of racial disparities in homelessness. Hous. Policy Debate 32, 940–967 (2022).

Jones, M. M. Does race matter in addressing homelessness? A review of the literature. World Med. Health Policy 8, 139–156 (2016).

Kaur, H. et al. Understanding the health and housing experiences of refugees and other migrant populations experiencing homelessness or vulnerable housing: a systematic review using GRADE-CERQual. CMAJ Open 9, e681–e692 (2021).

Olivet, J. et al. Racial inequity and homelessness: findings from the SPARC study. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 693, 82–100 (2021).

Paul, D. W. et al. Racial discrimination in the life course of older adults experiencing homelessness: results from the HOPE HOME study. J. Soc. Distress Homeless. 29, 184–193 (2020).

Zerger, S. et al. Differential experiences of discrimination among ethnoracially diverse persons experiencing mental illness and homelessness. BMC Psychiatry 14, 353 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Sosnowski for assistance with the literature search, as well as A. Abramovich, S. Canham, A. Durbin, J. Ecker, S. Kidd, N. Kozloff and P. O’Campo for their feedback on the special populations section of this article. This work was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR Foundation Grant Number 143259). The funder did not have any involvement in the preparation of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors collaboratively conceptualized this Review. N.K. drafted the Review, with input and critical review by V.S. Both authors read and approved the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Mental Health thanks Jed Boardman, Seena Fazel and Debbie Robson for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kerman, N., Stergiopoulos, V. Addressing health needs in people with mental illness experiencing homelessness. Nat. Mental Health 2, 354–366 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-024-00218-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-024-00218-0