Abstract

The ability to extend the time scale of the coherent optical response from large ensembles of quantum emitters is highly appealing for applications in quantum information devices. In semiconductor nanostructures, spin degrees of freedom can be used as auxiliary, powerful tools to modify the coherent optical dynamics. Here, we apply this approach to negatively charged (In,Ga)As/GaAs self-assembled quantum dots which are considered as excellent quantum emitters with robust optical coherence and high bandwidth. We study three-pulse spin-dependent photon echoes subject to moderate transverse magnetic fields up to 1 T. We demonstrate that the timescale of coherent optical response can be extended by at least an order of magnitude by the field. Without magnetic field, the photon echo decays with T2 = 0.45 ns which is determined by the radiative lifetime of trions T1 = 0.26 ns. In the presence of the transverse magnetic field, the decay of the photon echo signal is given by spin dephasing time of the ensemble of resident electrons T2,e ∼ 4 ns. We demonstrate that the non-zero transverse g-factor of the heavy holes in the trion state plays a crucial role in the temporal evolution and magnetic field dependence of the long-lived photon echo signal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The coherent optical response, which results after resonant excitation of quantum emitters with multiple optical pulses, carries rich information about the energy structure and dynamical properties of the studied system1,2. Moreover, it can be used for applications in quantum memories where light–matter interaction is used to store and retrieve optical fields in the form of photon echoes (PE)3,4,5. In solid-state systems based on color centers and rare earth ions, significant progress has been achieved in that respect6,7,8,9,10,11. Yet, the search for new systems where similar or alternative approaches can be pursued on much faster time scales is of great interest12,13,14,15,16.

Excitons in semiconductor nanostructures can be addressed resonantly by sub-ps optical pulses on very short timescales enabling access to exceptionally high bandwidths, but unavoidably leading to a short radiative lifetime, which imposes limitation on the optical storage time. One of the solutions is to use the spin degrees of freedom of resident electrons in semiconductors which makes it possible to extend the timescale of coherent optical response by several orders of magnitude15,17. The demonstration of this concept has been achieved for localized charged excitons in CdTe/(Cd,Mg)Te quantum well structures and donor-bound excitons in bulk ZnO crystals18. It is based on resonant excitation of the donor bound exciton D0X or negatively charged exciton (trion) X− with a sequence of three resonant optical pulses in the presence of a transverse magnetic field15. This allows one to transfer the optical coherence of trions into the electron spin coherence of resident electrons with a significantly longer relaxation time.

For realistic quantum memory protocols it is necessary to apply resonant optical pulses with an area of π, i.e. to perform robust Rabi flops. This is very difficult in semiconductor quantum wells and bulk crystals due to the strong damping of Rabi oscillations by excitation-induced dephasing19,20. Moreover, weakly localized resident carriers hop between the localization sites which leads to an additional loss of the coherence21. Therefore, it is advantageous to use quantum dots (QDs) with strong localization potential which ensures robust coherence properties16,22,23,24,25. Experiments with an ensemble of QDs are challenging due to the strong inhomogeneous broadening of optical transitions. In quantum wells the optical transitions for exciton and trion are spectrally separated and, therefore, they can be selectively addressed by proper choice of the photon energy of excitation. This selectivity is not available in a QD ensemble which imposes serious restrictions for observation and subsequent application of the photon echo retrieved from resident electrons. Therefore, the demonstration of long-lived spin-dependent echoes in QDs remained unresolved.

In this work, we demonstrate that in spite of strong inhomogeneous broadening it is possible to perform a robust transfer between the optical and spin coherence and to observe long-lived spin-dependent photon echoes (LSPE) in an ensemble of charged self-assembled QDs in a moderate transverse magnetic field. Moreover, in self-assembled (In,Ga)As/GaAs QDs the Zeeman splitting of the hole is of the same order of magnitude as that of the electron. We demonstrate that the heavy-hole splitting has a strong impact on the formation of three-pulse LSPE. In order to understand and describe properly the dynamics of LSPE in self-assembled QDs and its dependence on magnetic field, we develop a model, that accounts for both the electron and heavy-hole Zeeman splittings.

Results

Coherent optical response in (In,Ga)As QDs

We study n-doped (In,Ga)As quantum dots structures embedded into the microcavity with GaAs/AlAs distributed Bragg reflectors (for details see the “Methods” section). The QD emission is represented by the photoluminescence (PL) spectrum in Fig. 1a which was measured from the edge of the sample in order to avoid the cavity impact (blue dotted line). The PL maximum at the photon energy of 1.4355 eV corresponds to the radiative recombination of excitons from the lowest confined energy state, while a weak shoulder at higher energies around 1.45 eV is apparently related to the emission from the first excited exciton states. The width of the PL line reflects the magnitude of inhomogeneous broadening for the optical transitions with the full width at the half maxima (FWHM) of 10 meV. The corresponding transmission spectrum with a band centered at 1.434 eV and FWHM of 1.4 meV is shown by the red dashed line in Fig. 1a. Using a microcavity with a quality factor Q ~ 1000 facilitates the efficient generation of non-linear coherent optical signal due to the significant increase of light–matter interaction24,26,27.

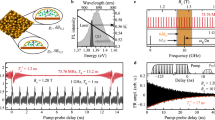

a Photoluminescence (PL, doted line) and transmission (dashed line) spectra of the sample measured at the temperature T = 6 K. The PL spectrum is shown for lateral emission from the edge of the sample in the direction parallel to its plane, e.g. along x-axis. The laser spectrum is shown with a solid line. b Sketch of the photon echo experiment. (In,Ga)As quantum dots (QDs) are embedded in a microcavity with GaAs/AlAs distributed Bragg reflectors (DBR). c Blue line shows the transient four-wave mixing (FWM) signal measured in kS = 2k2−k1 direction for τ12 = 33.3 ps and τ23 = 100 ps. The signal is represented by the two-pulse PE (2PE) at 67 ps and the three-pulse PE (3PE) at 167 ps. The three peaks with filled area show the temporal position of excitation laser pulses. Labels on top correspond to the polarization of excitation and detection in the HVVH configuration. H and V correspond to linear polarizations along x and y axes, respectively.

Transient four-wave mixing experiments with heterodyne detection are performed at a temperature T = 2 K and a magnetic field is applied in the plane of the sample (see the “Methods” section and Fig. 1c). The time-resolved electric field amplitude of the four-wave mixing signal is shown in Fig. 1c by the blue line for τ12 = 33.3 ps and τ23 = 100 ps, where τij is the time delay between pulses i and j in the sequence. Two- and three-pulse echoes are observed at times t = 2τ12 (2PE) and t = 2τ12 + τ23 (3PE), respectively. They are well described by Gaussian peaks with the FWHM of about 10 ps which is mainly determined by the spectral width of the excitation pulses16.

In what follows we use the magnitude of the electric field amplitude at the PE peak maximum ∣PPE∣ to characterize the strength of the photon echo signal. Note that the data in Fig. 1c correspond to a single scan where the areas of the excitation pulses are set below π/2 which results in simultaneous appearance of both 2PE and 3PE signals. In the next sections we present the two-pulse PE data for excitation with areas of pulses 1 and 2 approximately equal to π/2 and π, respectively. As for the three-pulse PE data we use a sequence of three π/2 pulses. The pulse energy of \({{{{{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}}}}=5\) pJ corresponds to the pulse area of about π. We note that the areas of excitation pulses do not change the temporal dynamics of the 2PE and 3PE signals as function of τ12 and τ23, which is the main task of our study. They influence the amplitude of echoes and their ratio. Under optimal conditions the fluence of a PE pulse is estimated to be about 0.5 fJ.

In order to address various spin configurations, we use different linear polarization schemes in the excitation and detection paths. The direction of polarization is assigned with respect to the magnetic field direction, i.e. H and V polarizations are parallel and perpendicular to B, respectively. The polarization scheme is labeled as ABD or ABCD for two- or three- pulse echoes. Here, the first two (AB) or three (ABC) letters indicate the linear polarizations of the optical pulses in the excitation sequence and the last letter (D) corresponds to the polarization direction in the detection, e.g. the data in Fig. 1c are taken in the HVVH polarization configuration.

Photon echo from trions in QDs

In order to observe long-lived spin-dependent echoes it is necessary to address trion X− (charged exciton) complexes, which correspond to the elementary optical excitation in a charged QD. The energy spectrum in the charged QD can be well described by a four-level energy scheme with Kramers doublets in the ground and excited states at B = 0, which are determined by the spin of the resident electron S = 1/2 and the angular momentum of the heavy hole J = 3/2, as shown in Fig. 2a. In contrast to the exciton in a neutral QD, this four-level scheme allows establishing optically induced long-lived spin coherence in the ground state17.

a Energy level diagram and optical transitions for the trion X−. H and V indicate the polarization of optical transitions. b Polar plots of two-pulse photon echo (PE) amplitude in HRH (solid line) and HRV (dashed line) polarization configurations at t = 2τ12 = 132 ps as function of polarization angle φ2 of the second pulse. H and V correspond to linear polarizations along x and y axes, respectively. Linear polarization R is defined by the angle φ2 with respect to the x-axis. c Decay of the two-pulse (2PE) and three-pulse (3PE) photon echoes as function of 2τ12 and τ23. In the three-pulse photon echo the delay time τ12 = 33.3 ps. The two-pulse photon echo decays exponentially with T2 = 0.45 ns (blue circles). The three-pulse PE shows exponential decay with a short time constant of T1 = 0.26 ns superimposed on the long-lived offset (green triangles). Dashed red curves show the corresponding exponential fits.

Although the photon energies for resonant excitation of trion and exciton (X) complexes are different in one and the same QD, it is not possible to perform selective excitation of only charged QDs by proper choice of the photon energy. This is due to the strong degree of inhomogeneous broadening for optical transitions in the QD ensemble, which is considerably larger than the energy difference between the X and X− resonances. It is, however, possible to distinguish between exciton and trion contributions using polarimetric measurement of photon echo signal28,29. Figure 2b shows polar plots of two-pulse PE magnitude measured at τ12 = 66 ps using HRH and HRV polarization schemes. The diagrams are obtained by rotation of the polarization direction of the second pulse with linear R-polarization which is defined by angle φ2 with respect to the H-polarization. In both polarization schemes, the signal is represented by rosettes with fourth harmonic periodicity when the angle φ2 is scanned. Such behavior corresponds to PE response from trions where the PE is linearly polarized with the angle φPE = 2φ2 and the PE amplitude is independent of φ229. In case of the neutral exciton the polar plot is different because the PE signal is co-polarized with the second pulse (φPE = φ2) and it amplitude follows \(| \cos {\varphi }_{2}|\).

We note that the small increase of the PE amplitude by about 15% in HHH as compared to HVH remains the same under rotation of the sample around z-axis which excludes an anisotropy of dipole matrix elements in xy-plane as possible origin of asymmetry (see the blue pattern in Fig. 2b). The difference could be provided by a weak contribution from neutral excitons. This is because in HRH configuration the PE from trions is the four-lobe pattern \(\propto | \cos^{2}{\varphi }_{2}|\) while for excitons it corresponds to a two-lobe pattern \(\propto {\cos }^{2}{\varphi }_{2}\). Finally, we conclude that independent of the polarization scheme the main contribution to the coherent optical response with a photon energy of 1.434 eV in the studied sample is attributed to trions. This demonstration is very important for proper interpretation of the results because long-lived spin-dependent echoes can be observed only in charged QDs. Moreover it has large impact for applications in quantum memory protocols where high efficiency is required.

We evaluate the optical coherence time T2 and the population lifetime T1 of trions in QDs from the decay of PE amplitude of the two- and three-pulse echoes, respectively. The data measured at B = 0 in co-polarized configuration (HHH for 2PE and HHHH for 3PE) are shown in Fig. 2c. In the case of 2PE, the amplitude is scanned as a function of 2τ12 (blue dots), while for 3PE the dependence on τ23 is shown (green triangles). The exponential fit of two-pulse echo \(| {P}_{{{{{{{{\rm{2PE}}}}}}}}}| \propto \exp (-2{\tau }_{12}/{T}_{2})\) gives T2 = 0.45 ns which is in agreement with previous studies in (In,Ga)As/GaAs QDs16,22,24. The decay of 3PE has a more complex structure. At short delay times, its magnitude decays exponentially with a time constant of T1 = 0.27 ns which we attribute to the trion lifetime τr. However, the signal does not decay to zero and shows a small offset with a magnitude of about 5% of the initial amplitude at long delay times t > 1 ns. This weak signal is governed by the dynamics of population grating in the ground state of the QDs ensemble and can be provided by many different reasons, which are out of the scope of this paper. We note that T2 ≈ 2T1 indicates that the loss of optical coherence under resonant excitation of trions is governed by their radiative recombination.

Long-lived spin-dependent photon echo in QDs

Application of the transverse magnetic field (B∣∣x) leads to Zeeman splitting of the Kramers doublets in the ground resident electron and optically excited trion states. The electron spin states with spin projections Sx = ±1/2 are split by ℏωe = geμBB, while the trion states with angular momentum projections Jx = ±3/2 are split by ℏωh = ghμBB. Here, ωe and ωh are the Larmor precession frequencies of electron and heavy hole spins, ge and gh are the electron and hole g factor, and μB is the Bohr magneton. Optical transitions between all four states are allowed using light with H or V linear polarization, as shown in Fig. 2a. The energy structure can be considered as composed of two Λ schemes sharing common ground states. The magnetic field induces the asymmetry between these two Λ schemes allowing one to transfer optical coherence induced by the first optical pulse into the spin coherence by application of the second optical pulse15,17.

The first pulse creates two independent coherent superpositions between the ground and excited states (optical coherences). For an H-polarized pulse the optical coherences correspond to the density matrix elements ρ13 and ρ24 (see Fig. 2a and Supplementary Note 1). The second pulse creates the populations ρii (i = 1, 2, 3, 4) for H-polarization or accomplishes transfer of optical coherences into the spin coherences of trions (ρ34) and electrons (ρ12) when the second pulse is V-polarized. Due to inhomogeneous broadening of the optical resonance frequencies ω0 optical excitation with a sequence of two pulses leads to appearance of population (co-polarized HH-sequence) or spin (cross-polarized HV-sequence) gratings in the spectral domain with the period of 1/τ12. For the HH-sequence at zero magnetic field the population gratings in the left and right arms of the optical scheme are equal, i.e. ρ11 = ρ22 and ρ33 = ρ44 (see Fig. 2a). However, in magnetic field due to the Zeeman splitting of electrons and holes, a spin grating for the component directed along magnetic field appears. For the HV-sequence the spin grating is given by the yz components.

Thus, a sequence of two-linearly polarized pulses can be used to initialize a spin grating in the ground and excited states. The addressed spin components depend on the polarization of the exciting pulses. For linearly co-polarized HH sequence the spin components along the magnetic field direction (x-axis) are addressed (see Supplementary Eq. (35)

In case of cross-polarized HV sequence the spin grating is produced in the plane perpendicular to the magnetic field direction (see Supplementary Eqs. (36) and (37)

The evolution of spin gratings for trions and resident electrons is governed by their population and spin dynamics in magnetic field. The hole spin grating lifetime is limited by the trion lifetime. The electron spin grating in the ground state is responsible for the long-lived spin-dependent echo which appears if the third pulse is applied. The latter transforms the spin grating back into the optical coherence, leading to the appearance of the photon echo after the rephasing time τ1215. The decay of LSPE as a function of τ23 is governed by the spin dynamics of resident electrons. HHHH and HVVH polarization schemes give access to longitudinal T1,e and transverse \({T}_{{{{{{{{\rm{2,e}}}}}}}}}^{* }\) spin relaxation times, respectively.

In the studied (In,Ga)As/GaAs QDs the value of gh = 0.18 is of the same order of magnitude as the electronic g-factor ge = −0.5230. Therefore, it should be taken into account in contrast to previous studies where the Zeeman splitting in the trion state was neglected. In addition, it should be noted that the PE signal depends sensitively on the orientation of crystallographic axes with respect to the magnetic field direction due to the strongly anisotropic in-plane g-factor of the hole in semiconductor quantum wells and dots30,31. In our studies, the sample was oriented with the [110] crystallographic axis parallel to B which corresponds to the case when the H- and V-polarized optical transitions have the photon energies of ℏω0 ± ℏ(ωe − ωh) and ℏω0 ± ℏ(ωe + ωh), respectively.

The three-pulse PE amplitude as a function of delay time τ23 and magnetic field B are shown in Fig. 3. In full accord with our expectations, we observe that application of a moderate magnetic field B < 1 T drastically changes the dynamics of three-pulse PE. In HHHH polarization scheme the large offset emerges which decays on a timescale significantly longer than the repetition period of laser pulses, i.e. T1,e ≫ 10 ns. The short decay, which is also present at B = 0, with the time constant T1 = 0.26 ns is associated to the trion lifetime. In the HVVH polarization scheme, long-lived oscillatory signal appears which is attributed to the Larmor spin precession of resident electrons and decays exponentially with \({T}_{{{{{{{{\rm{2,e}}}}}}}}}^{* }\). At shorter delays, the signal behavior is more complex due to the superposition of spin-dependent signals from trions and resident electrons.

a Amplitude of three-pulse photon echo (3PE) as a function of τ23 for τ12 = 66 ps. The data are taken in co-polarized HHHH and cross-polarized HVVH polarization schemes at B = 0.3 and 0.1 T, respectively. H and V corresponds to linear polarization parallel and perpendicular to magnetic field, respectively. b Magnetic field dependence of long-lived spin-dependent photon echo for τ12 = 100 ps and τ23 = 2.033 ns. Top and bottom curves correspond to signal measured in HHHH (green triangles) and HVVH (blue circles) polarization schemes, respectively. Red lines present the results of the theoretical modeling using Eqs. (3) and (4) with the following parameters: ge = −0.516, gh = 0.18, TT = τr = T1 = 0.26 ns, T1,e = 23 ns, \({T}_{{{{{{{{\rm{2,e}}}}}}}}}^{* }\) is evaluated from T2,e = 4.3 ns and Δge = 0.004 using Eq. (5). The signals in HHHH polarization are shifted for clarity with the dashed line corresponding to zero signal level.

Further insight can be obtained from the magnetic field dependence of LSPE signal which is measured at the long delay τ23 = 2.033 ns when the contribution from trions in three-pulse PE is negligible (see Fig. 3b). The delay time τ12 is set to 100 ps which is shorter than the optical coherence T2. At zero magnetic field, the PE is absent in the HVVH polarization scheme and shows only very weak amplitude in HHHH configuration. An increase of magnetic field leads to the appearance of LSPE in both polarization configurations. For HHHH we observe a slow oscillation which is governed by Larmor precession of both electron and hole spins during τ12 when the spin grating is initialized by the sequence of two pulses. In the HVVH scheme the LSPE oscillates much faster because it is mainly determined by the Larmor precession of resident electron spins during τ23, which is roughly 20 times longer than τ12.

In order to describe the experimental results quantitatively, we extended the theory from Langer et al.15 by taking into account both electron and heavy-hole Zeeman splitting (for details see Supplementary Note 1). We analytically solve the Lindblad equation for the (4 × 4) density matrix to describe the temporal evolution between the first and second pulses for 0 < t < τ12 and after the third pulse for t > τ12 + τ23. The spin dynamics of trions and electrons in external magnetic field for τ12 < t < τ12 + τ23 is described by the Bloch equations. The three-pulse PE amplitude in HHHH scheme is given by

Here \({T}_{{{{{{{{\rm{T}}}}}}}}}^{-1}={\tau }_{{{{{{{{\rm{r}}}}}}}}}^{-1}+{T}_{{{{{{{{\rm{h}}}}}}}}}^{-1}\) is the spin lifetime of the trion. For moderate magnetic fields B ≤ 1 T we can assume that the spin relaxation time of hole in QDs Th is significantly longer than τr and, therefore, in our case TT = τr32. The first and second terms on the right hand side correspond to the trion contribution, while the last term is due to the LSPE from resident electrons.

For HVVH polarization we obtain

where for simplicity we introduce the following parameters: phases ϕe, ϕh and amplitudes re and rh. The subscript e, h corresponds to the electron or trion contributions which are given by the first and second terms on right-hand side in Eq. (4), respectively. The parameters are given by Supplementary Eqs. (55)-(57). They are determined by the Larmor precession frequencies ωe and ωh, delay time τ12, trion lifetime τr. The g-factors of electrons and holes are known from previous studies30,33. Therefore, the only unknown parameter is the spin dephasing time of resident electrons \({T}_{{{{{{{{\rm{2,e}}}}}}}}}^{* }\). Note that if the g-factors of electrons and holes are unknown they can be used as additional fitting parameters in the description below.

In order to determine \({T}_{{{{{{{{\rm{2,e}}}}}}}}}^{* }(B)\), we fit the transient signals in HVVH polarization for different magnetic fields as shown exemplary for the transient at B = 0.1 T by the solid red line in Fig. 3a. For the LSPE when τ23 ≫ τr = T2/2 only the second term in Eq. (4) remains, which simplifies the fitting procedure. Three parameters of the LSPE signal, i.e. decay rate \(1/{T}_{{{{{{{{\rm{2,e}}}}}}}}}^{* }\), amplitude re, and phase ϕe, were extracted from the fit which are plotted as blue dots in Fig. 4 as a function of the magnetic field. It follows from Fig. 4a that the spin dephasing rate increases linearly with the increase of B. Such behavior is well established in ensembles of QDs and it is related to the fluctuations of electron g-factor value in different QDs32. It can be described as

where T2,e is the transverse spin relaxation time and Δge is the inhomogeneous broadening of the electron g-factor. The linear fit with this expression shown in Fig. 4a by the red dashed line gives T2,e = 4.3 ns and Δge = 4 × 10−3.

Magnetic field dependence of the main parameters (decay rate, phase and amplitude) of long-lived spin-dependent photon echo signal evaluated from the three-pulse transients PHVVH(τ23) measured at different B. a decay rate \(\hslash /{T}_{{{{{{{{\rm{2,e}}}}}}}}}^{* }\); b phase ϕe; c amplitude re. Blue points correspond to the data resulting from the fit using the last term on the right-hand side in Eq. (4). Error bars represent confidence interval evaluated from the fit. In a and c the error is given by the size of the symbol. Red dashed line in a is the fit by linear function from Eq. (5) with T2,e = 4.3 ns and Δge = 4 × 10−3. Red solid line in b and c—magnetic field dependences of ϕe and re given by Supplementary Eqs. (56) and (57).

The parameter ϕe in Fig. 4b starts from −0.8 rad in magnetic fields below 0.1 T and approaches zero in fields above 0.8 T. The amplitude re in Fig. 4c gradually rises with an increase of B up to 0.4 T and remains the same in larger magnetic fields. We calculate the magnetic field dependence of amplitude and phase of LSPE using Supplementary Eqs. (56) and (57), respectively, using ge = −0.516, gh = 0.18, TT = τr = 0.26 ns and τ12 = 33.3 ps. The resulting curves are shown by red solid lines in Fig. 4 and are in excellent agreement with the experimental data. We note that in the limit of large magnetic fields, which corresponds to the condition of ∣(ωe−ωh)∣τ12 ≫ 1, the amplitude of LSPE saturates (re → 1) and the phase of the signal approaches zero (ϕe → 0) which gives the simple expression \({P}_{{{{{{{{\rm{HVVH}}}}}}}}}\propto \cos [{\omega }_{{{{{{{{\rm{e}}}}}}}}}{\tau }_{23}+({\omega }_{{{{{{{{\rm{e}}}}}}}}}-{\omega }_{{{{{{{{\rm{h}}}}}}}}}){\tau }_{12}]\) for a long-lived signal at τ23 ≫ τr. We emphasize that this expression takes into account the non-zero g-factor of the hole gh which plays an important role in the formation of the LSPE signal.

After evaluation of \({T}_{{{{{{{{\rm{2,e}}}}}}}}}^{* }(B)\), we can reproduce the LSPE signals as a function of τ23 and B using Eqs. (3) and (4) which are shown by red curves in Fig. 3 in both HHHH and HVVH polarization configurations. Here, the longitudinal spin relaxation time T1,e is set to 23 ns. In general this relaxation process can be neglected because T1,e strongly exceeds τ23. Excellent agreement is obtained at all time delays and magnetic fields. We note that the small discrepancies in HHHH polarization configuration at the magnetic fields around 0 and 1 T are attributed to the presence of a weak background signal possibly due to a population grating in the ground states as previously discussed for the case of Fig. 2c. Nevertheless, importantly the HVVH configuration which corresponds to fully coherent transformation between optical and spin coherence is free from any background.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that the spin degrees of freedom can be used for substantial temporal extension of the coherent optical response in self-assembled (In,Ga)As QDs which has important implications for applications of this system in quantum memory devices with high bandwidth. In particular, we show that despite the strong inhomogeneous broadening of optical transitions in the ensemble of quantum dots it is possible to store and retrieve the optical coherence in the spin ensemble of resident electrons and to extend the optical coherence time by about an order of magnitude from 0.5 to 4 ns. This is manifested in the emergence of long-lived spin-dependent photon echo signals under resonant excitation of trions in (In,Ga)As/GaAs quantum dots in the presence of a moderate transverse magnetic field. The LSPE decay time of 4 ns is not the ultimate limit for the system under study. It is attributed to spin dephasing of resident carriers in the effective fluctuating magnetic fields created by the nuclei via the hyperfine interaction34,35. Since the fluctuation of nuclei spins differs from one QD to another this leads to dephasing on the time scale of several ns. Application of spin echo techniques in combination with dynamic decoupling can be used to extend the decay time further into the microsecond range36,37,38. Note that the longitudinal spin relaxation can be much longer reaching time scales up to several seconds39.

In our study the extention of time for coherent optical response is comparable to what we observed in CdTe quantum well structures15. However, LSPE in quantum dots has significant advantages in comparison to quantum wells. In particular, Rabi flopping using intensive laser pulses with areas of multiple π works much better in QDs than in quantum wells16. This influences the efficiency of retrieval because optically driven Rabi flops are required in quantum memory protocols when the control pulses are applied (second and third pulses). Moreover, Rabi flops are essential for implementation of revival in a silenced echo scheme, which is used to eliminate the noise due to spontaneous emission from optically excited states7. Another important point, which is related to the efficiency of retrieval, is the optimization of the microcavity parameters. In the investigated structures we exploited the enhancement of light–matter interaction by placing the QD layers in the antinodes of the 5/2λ microcavity without taking its impedance into account. As a result, such enhancement allowed us to obtain Rabi flops already for moderate excitation pulse fluencies (5 pJ corresponds to pulse area of π). Yet the detected PE signals are still relatively weak being on the order of several 1000s of photons per photon echo pulse. We attribute such large losses due to insufficient impedance matching which requires optimization as discussed in the literature40,41. We also note that for realistic quantum memory device, it would be necessary to use a different protocol where, for example selective excitation of only one of the excited trion spin states is involved. Nevertheless, our results do not impose any limitations here. In contrast, we demonstrate that most of the QDs which are addressed optically are charged allowing for a substantial temporal extension of the coherent optical response in the ensemble of QDs.

Methods

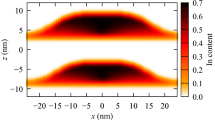

Sample

The studied sample was grown by molecular beam epitaxy. It consists of 4 layers of n-doped rapid thermal annealed (In,Ga)As QDs in a GaAs matrix, embedded in the antinodes of the standing wave electric field in the microcavity. The QDs in each layer have a density of about 1010 cm−2. The resident electrons were supplied to the QDs by introducing δ-doping with Si donors at a distance of 64.5 nm below each QD layer. After the epitaxial growth, the sample was annealed at the temperature of 900 °C to reduce the inhomogeneous broadening of the optical transitions30,42.

The 5/2λ microcavity is formed by 11 and 14 pairs of GaAs/AlAs layers in the top and bottom distributed Bragg reflectors, respectively, having a gradient axis in the plane of the sample along which the energy of photonic mode can be tuned. All the experiments were performed in the sample area where the photon energy of the cavity mode is in resonance with the emission peak of QDs (see Fig. 1).

Transient four-wave mixing technique

The sample is mounted in a liquid helium bath magneto-optical cryostat and cooled down to a temperature T = 2 K unless stated otherwise. Laser pulses with a duration of 2.5 ps at a repetition rate of 75.75 MHz were generated by a tunable mode-locked Ti:Sapphire oscillator. The spectral width of the laser pulses with FWHM of 0.5 meV is approximately three times narrower than the photonic mode of the cavity, i.e. the excitation pulses are not distorted by the cavity [see the green solid line in the Fig. 1a]. The magnetic field B is applied parallel to the sample plane. Photon echoes are generated by a sequence of laser pulses focused into a spot of 250 μm using a concave mirror with the focal distance of 50 cm. The laser beams enter the sample under incidence close to normal with wavevectors ki (i is the pulse number), as it is shown in Fig. 1b. The incidence angles of the first and second (third) pulses are given by 3/50 and 2/50 rad, respectively, which are small enough to neglect the microcavity dispersion. Since k2 = k3 the signals resulting from the two- and three-pulse excitation sequences are emitted in the same direction. The resulting transient four-wave mixing signal is detected in reflection geometry in the direction of kS = 2k2 − k1 using heterodyne detection2,18.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Smallwood, C. L. & Cundiff, S. T. Multidimensional coherent spectroscopy of semiconductors. Laser Photonics Rev. 12, 1800171 (2018).

Borri, P. & Langbein, W. In Transient Four-wave mixing of Excitons in Quantum dots from Ensembles and Individuals in Semiconductor Qubits (eds Henneberger, F. & Benson, O.) (Pan Stanford, Singapore, 2008).

Moiseev, S. A. & Kröll, S. Complete reconstruction of the quantum state of a single-photon wave packet absorbed by a Doppler-broadened transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 173601 (2001).

Lvovsky, A. I., Sanders, B. C. & Tittel, W. Optical quantum memory. Nat. Photonics 3, 706 (2009).

Tittel, W. et al. Photon echo quantum memory in solid state systems. Laser Photonics Rev. 4, 244 (2010).

Clausen, C. et al. Quantum storage of photonic entanglement in a crystal. Nature 469, 508–511 (2011).

Damon, V., Bonarota, M., Louchet-Chauvet, A., Chanelière, T. & Le Gouët, J.-L. Revival of silenced echo and quantum memory for light. N. J. Phys. 13, 093031 (2011).

Zhong, T. et al. Nanophotonic rare-earth quantum memory with optically controlled retrieval. Science 357, 1392–1395 (2017).

Ma, Y. et al. Elimination of noise in optically rephased photon echoes. Nat. Commun. 12, 4378 (2021).

Minnegaliev, M. M., Gerasimov, K. I., Urmancheev, R. V., Zheltikov, A. M. & Moiseev, S. A. Linear Stark effect in Y3Al5O12:Tm3+ crystal and its application in the addressable quantum memory protocol. Phys. Rev. B 103, 174110 (2021).

Askarani, M. F. et al. Long-lived solid-state optical memory for high-rate quantum repeaters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 220502 (2021).

Bustard, P. J., Lausten, R., England, D. G. & Sussman, B. J. Toward quantum processing in molecules: a THz-bandwidth coherent memory for light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 083901 (2013).

England, D. G. et al. Storage and retrieval of THz-bandwidth single photons using a room-temperature diamond quantum memory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 053602 (2015).

Langer, L. et al. Magnetic-field control of photon echo from the electron-trion system in a CdTe quantum well: shuffling coherence between optically accessible and inaccessible states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 157403 (2012).

Langer, L. et al. Access to long-term optical memories using photon echoes retrieved from semiconductor spins. Nat. Photonics 8, 851 (2014).

Kosarev, A. N. et al. Accurate photon echo timing by optical freezing of exciton dephasing and rephasing in quantum dots. Commun. Phys. 3, 228 (2020).

Salewski, M. et al. High-resolution two-dimensional optical spectroscopy of electron spins. Phys. Rev. X 7, 031030 (2017).

Poltavtsev, S. V., Yugova, I. A., Akimov, I. A., Yakovlev, D. R. & Bayer, M. Photon echo from localized excitons in semiconductor nanostructures. Phys. Solid State, 60, 1635–1644 (2018).

Patton, B., Woggon, U. & Langbein, W. Coherent control and polarization readout of individual excitonic states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 266401 (2005).

Poltavtsev, S. V. et al. Damping of Rabi oscillations in intensity-dependent photon echoes from exciton complexes in a CdTe/(Cd,Mg)Te single quantum well. Phys. Rev. B 96, 075306 (2019).

Kosarev, A. N. et al. Microscopic dynamics of electron hopping in a semiconductor quantum well probed by spin-dependent photon echoes. Phys. Rev. B 100, 121401(R) (2019).

Borri, P., Langbein, W., Schneider, S. & Woggon, U. Ultralong dephasing time in InGaAs quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 157401 (2001).

Suzuki, T. et al. Coherent control of the exciton-biexciton system in an InAs self-assembled quantum dot ensemble. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 157402 (2016).

Poltavtsev, S. V. et al. Photon echo transients from an inhomogeneous ensemble of semiconductor quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 93, 121304(R) (2016).

Wigger, D. et al. Rabi oscillations of a quantum dot exciton coupled to acoustic phonons: coherence and population readout. Optica 5, 1442–1450 (2018).

Fras, F. et al. Multi-wave coherent control of a solid-state single emitter. Nat. Photon. 10, 155–158 (2016).

Salewski, M. et al. Photon echoes from (In,Ga)As quantum dots embedded in a Tamm-plasmon microcavity. Phys. Rev. B 95, 035312 (2017).

Moody, G. et al. Fifth-order nonlinear optical response of excitonic states in an InAs quantum dot ensemble measured with two-dimensional spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 87, 045313 (2013).

Poltavtsev, S. V. et al. Polarimetry of photon echo on charged and neutral excitons in semiconductor quantum wells. Sci. Rep. 9, 5666 (2019).

Trifonov, A. V. et al. Homogeneous optical anisotropy in an ensemble of InGaAs quantum dots induced by strong enhancement of the heavy-hole band Landé parameter q. Phys. Rev. B 104, L161405 (2021).

Poltavtsev, S. V. et al. In-plane anisotropy of the hole g factor in CdTe/(Cd,Mg)Te quantum wells studied by spin-dependent photon echoes. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 023160 (2020).

Greilich, A. et al. Optical control of spin coherence in singly charged (In,Ga)As/GaAs quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 227401 (2006).

Kamenskii, A. N. et al. Detection and amplification of spin noise using scattered laser light in a quantum-dot microcavity. Phys. Rev. B 101, 041401(R) (2020).

Merkulov, I. A., Efros, A. L. & Rosen, M. Electron spin relaxation by nuclei in semiconductor quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 65, 205309 (2002).

Glazov, M. M. Electron and Nuclear Spin Dynamics in Semicodnuctor Nanostructures (Oxford University Press, UK, 2018).

Greilich, A. et al. Mode locking of electron spin coherences in singly charged quantum dots. Science 313, 341 (2006).

Bechtold, A. et al. Three-stage decoherence dynamics of an electron spin qubit in an optically active quantum dot. Nat. Phys. 11, 1005 (2015).

Huthmacher, L. et al. Coherence of a dynamically decoupled quantum-dot hole spin. Phys. Rev. B 97, 241413 (2018).

Gillard, G. et al. Fundamental limits of electron and nuclear spin qubit lifetimes in an isolated self-assembled quantum dot. npj Quantum Inf. 7, 43 (2021).

Afzelius, M. & Simon, C. Impedance-matched cavity quantum memory. Phys. Rev. A 82, 022310 (2010).

Moiseev, S. A., Andrianov, S. N. & Gubaidullin, F. F. Efficient multimode quantum memory based on photon echo in an optimal QED cavity. Phys. Rev. A 82, 022311 (2010).

Langbein, W. et al. Radiatively limited dephasing in InAs quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 70, 033301 (2004).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through the International Collaborative Research Centre TRR 160 (Projects A3 and A1). A.V.T. and I.A.Y. thank the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (Project No. 19-52-12046) and the Saint Petersburg State University (Grant No. 73031758). A.L. and A.D.W. gratefully acknowledge financial support from the grants DFH/UFA CDFA05-06, DFG project 383065199, and BMBF Q.Link.X 16KIS0867.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.N.Ko., A.V.T., I.I.Y., S.V.P., and A.N.Ka. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. A.V.T. and I.A.Y. developed the theoretical model. C.E.S., C.S., A.L. and A.W. fabricated the samples. A.N.Ko., A.V.T, I.A.Y., S.V.P, D.R.Y, M.B., and I.A.A. conceived the idea for the experiment and co-wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kosarev, A.N., Trifonov, A.V., Yugova, I.A. et al. Extending the time of coherent optical response in ensemble of singly-charged InGaAs quantum dots. Commun Phys 5, 144 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-022-00922-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-022-00922-2

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.