Abstract

Patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) have a low nutritional status and a high mortality risk. The geriatric nutritional risk index (GNRI) is a predictive marker of malnutrition. However, the association between unplanned hemodialysis (HD) and GNRI with mortality remains unclear. In total, 162 patients underwent HD at our hospital. They were divided into two groups: those with unplanned initiation with a central venous catheter (CVC; n = 62) and those with planned initiation with prepared vascular access (n = 100). There were no significant differences in sex, age, malignant tumor, hypertension, and vascular disease, while there were significant differences in the times from the first visit to HD initiation (zero vs. six times, p < 0.001) and days between the first visit and HD initiation (5 vs. 175 days, p < 0.001). The CVC insertion group had significantly lower GNRI scores at initiation (85.7 vs. 99.0, p < 0.001). The adjusted hazard ratios were 4.002 and 3.018 for the GNRI scores and frequency, respectively. The 3-year survival rate was significantly lower in the CVC + low GNRI group (p < 0.0001). The GNRI after 1 month was significantly inferior in the CVC insertion group. Inadequate general management due to late referral to the nephrology department is a risk factor for patients with ESRD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

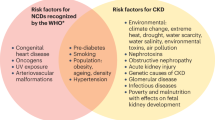

The number of patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring renal replacement therapy (RRT) is increasing worldwide1,2. As the elderly population increases, a higher proportion of frail patients needing dialysis is emerging globally. Although the development of hemodialysis (HD) management helps prolong patients’ lifespans, it is well known that inadequate preparation, such as an unplanned HD initiation that needs emergent central venous catheter (CVC) insertion affects mortality3. Compared to arteriovenous fistulas, CVC insertion has a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.53 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.41–1.67) for all-cause mortality4; hence, HD with CVC is considered a risk factor for mortality. The arteriovenous fistulas should be created at 4 weeks before the scheduled HD initiation, as it takes at least 2 weeks for maturation5. This suggests that patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) should be referred to the nephrology department at the appropriate time, with the access prepared before initiation of dialysis initiation6, since late referral to nephrologists could lead to unfavorable outcomes7,8,9.

In contrast, patients with ESRD and uremia can develop malnutrition10, with a prevalence of 28–54% in patients undergoing HD11. Wei et al. showed that malnutrition could be associated with frailty, a geriatric syndrome that reflects multisystem physiological dysregulation12. Indeed, malnutrition in patients with ESRD and prefrailty/frailty was reported to be a significant risk factor for poor outcomes11,12.

Several prediction scores for the mortality of malnourished patients with ESRD have been investigated broadly. Biochemical indices, such as serum albumin, C-reactive protein, and ferritin levels, are well-known prediction markers. In contrast, the physical index described by a subjective global assessment, subjective global assessment-dialysis malnutrition, malnutrition inflammation, and geriatric nutrition risk index (GNRI) scores have also been studied and can be used to evaluate the nutritional status13,14,15,16. GNRI was originally developed by Bouillanne et al.17 for identifying geriatric hospitalized patients with a nutritional risk and is based on simple indices, such as serum albumin levels and patient’s bodyweight. To date, several studies have shown that the GNRI, as one of the prognostic indices, can be used to predict the mortality of frail patients with CKD undergoing HD7,8,18.

GNRI at the time of initiation of dialysis is valuable for predicting mortality (GNRI low, 22.2% vs. GNRI high, 12.6%, p < 0.001)19. Although many studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of the GNRI as a predictive marker in the management of CKD or maintenance of patients with frailty and malnutrition undergoing HD, only a few have described whether the GNRI scores at HD initiation can impact the outcome of unplanned HD initiation following inadequate preparation due to late referral. Thus, we investigated whether the association between unplanned dialysis and nutritional status affected patient outcomes.

Results

Baseline characteristics

There was no significant between-group difference regarding sex, age, primary illness (such as active malignant tumors, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension), and past medical history, including ischemic heart disease, neurovascular disease, and peripheral artery disease (Table 1). Visit frequency until HD initiation was required for ESRD was significantly lower in the CVC insertion group than in the vascular access initiation group (zero vs. six times, respectively; p < 0.001). Similarly, the association of the number of days between the first visit and HD initiation (5 vs. 175 days, respectively; p < 0.001) and that between vascular access placement and HD were significantly lower in the CVC insertion than that in the vascular access initiation group (− 17 vs. 70 days, respectively; p < 0.001; the minus sign indicates that vascular access was created after HD initiation). Interestingly, there was a statistically significant between-group difference in the GNRI scores at HD initiation (CVC insertion vs. vascular access, 85.7 vs. 99.0%; p < 0.001), which was similar to the visit frequency. Unplanned HD with CVC insertion and a low GNRI score were considered consequences of late referral to the nephrology department.

Risk factors of patients’ outcomes on time of HD initiation

Next, we analyzed the relationship between visit frequency and the incidence of CVC insertion using an established receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (area under the curve, 0.874; p < 0.0001), with a value of 1 (one visit), which indicated the highest sensitivity and specificity (Fig. 1). Univariate Cox regression analysis showed that GNRI (low vs. high) at HD initiation and the visit frequency (≤ 1) were significant risk factors for poor outcomes (hazard ratio [HR], 3.781; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.766–8.096; p = 0.001 vs. HR, 4.064; 95% CI 1.809–9.130; p = 0.001), in addition to age (> 75 years old) and brain/cardiovascular disorders. Although age and brain/cardiovascular disorders are recognized as important factors for patients’ outcomes in patients with CKD (HR, 2.930; 95% CI 1.361–6.310; p = 0.006 vs. HR, 2.402; 95% CI 1.125–5.129; p = 0.025), the multivariate-adjusted Cox regression analysis also indicated that the GNRI scores and visit frequency were also significant risk factors for poor outcomes (HR, 4.002; 95% CI 1.608–9.964; p = 0.003 vs. HR, 3.018; 95% CI 1.258–7.239; p = 0.011; Table 2). Thus, these analyses revealed that the nutritional status and visit frequency also had a critical impact on survival outcomes.

ROC analysis based on the visit time for CVC insertion at HD initiation. In this model, the cut-off value of visit time is 1; sensitivity and specificity were 74.2% and 90.8%, respectively; the AUC was 0.874, p < 0.0001. AUC, area under the curve; CVC, central venous catheter; HD, hemodialysis; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Association of unplanned HD initiation and malnutrition prior to initiation with patient mortality

Next, we investigated whether the combination of malnutrition and HD initiation with CVC insertion could lower the all-cause mortality. Patients were divided into four groups according to their GNRI scores and CVC insertion: those with CVC + low GNRI score, those without CVC + low GNRI score, those without CVC + high GNRI score, and those with CVC + high GNRI score. Although the 3-year patient survival in the “with CVC + low GNRI” group was inferior (46.5%; p < 0.0001) as compared to the other groups, the remaining three groups were not significantly different (80.9, 88.9, and 71.6%; p = 0.5379; Fig. 2). Almost all the events occurred within 48 weeks of initiation.

The 3-year survival rates after HD initiation. We compared four groups based on two parameters: with CVC + low GNRI score, without CVC + low GNRI score, without CVC + high GNRI score, and with CVC + high GNRI score. Those who belonged to the group “with CVC + low GNRI” had the lowest survival rate (46.5%, p < 0.0001) compared to the other groups (80.9%, 88.9%, and 71.6%, respectively). CVC, central venous catheter; GNRI, geriatric nutritional risk index; HD, hemodialysis.

Furthermore, we analyzed the transition of the GNRI scores after HD initiation between CVC insertion and vascular access groups. The GNRI score was significantly lower in the CVC insertion group (median, interquartile range: 85.7 [80.3–99.0] points) compared to the vascular access group (99.0, [94.1–106.4] points; p < 0.001), and remained significantly lower even after 1 month (85.3 [76.1–90.2 vs. 93.6 [88.2–101.7] points; p < 0.001), showing that low GNRI scores persisted despite HD initiation (Fig. 3).

The transition of GNRI between HD initiation and 1 month after initiation. At the time of initiation, the GNRI score was significantly lower in the CVC group compared to that in the vascular access group. Similarly, at 1 month after initiation, the low value of GNRI persisted in the CVC insertion group. CVC, central venous catheter; GNRI, geriatric nutritional risk index; HD, hemodialysis.

Discussion

We analyzed the association between malnutrition and inadequate preparation for HD and identified that unplanned HD initiation due to late referral to a nephrology department could lead to poor patient outcomes. In this retrospective cohort study, although there were no significant between-group differences regarding age, sex, primary illness, and past medical history, the visit frequency and GNRI scores were significantly different, which implied that patients who underwent CVC insertion did not have sufficient time for the preparation of a vascular access. Visit frequency ≤ 1 could be the cut-off value to denote CVC insertion and unplanned HD initiation. The 3-year patient survival rate was significantly lower in the group with CVC and low GNRI scores as compared to the other combination groups. Furthermore, the GNRI scores of the CVC group also had a significantly lower value despite HD treatment.

The number of patients with ESRD is increasing worldwide, and more elderly patients are undergoing dialysis1. As the number of frail patients with CKD is increasing, physicians should manage patients’ health and consider their preferred choice—if renal function decreases and patients wish to undergo RRT, they should be referred to experts12. In a 2019 update, the Kidney Disease Outcome Quality Initiative (KDOQI) recommended that the ESRD life-plan should be discussed with the patient within a multidisciplinary team framework. A nephrologist should at least discuss modality options with the patient, with referral to a vascular access surgeon for input on the appropriate dialysis access that corresponds to the chosen RRT modality20. Especially, vascular access should be prepared at an appropriate time to avoid the risk of emergent CVC insertion. The Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy guidelines describe that vascular access construction should be considered for CKD stages 4 or 5 while considering clinical conditions, and an arteriovenous fistula should be constructed at least 2–4 weeks before the initial puncture21.

A previous study showed that an unplanned start of dialysis was associated with poor survival. Roy et al. demonstrated that the survival rates at 3 and 12 months were 38.6% vs. 90.9% and 14.4% vs. 73.6% for unplanned vs. planned dialysis, respectively (p < 0.001). These findings showed that insufficient preparation was a risk factor for these patients3. Indeed, immature vascular access due to late referral could lead to unplanned dialysis22. Conversely, elderly ESRD patients are less likely to undergo surgery for the creation of vascular access and have a higher likelihood of dying after HD initiation; hence, CVC itself could not be a risk factor for mortality in those populations23,24. However, there is no universal definition for referral timing in patients with CKD, and it varies across institutions25,26,27. Although the optimal cut-off value remains controversial, the most broadly accepted definition of late referral is the first encounter with an expert within 3–4 months prior to ESRD diagnosis6,28. Our clinical data also showed that the participants in the vascular access group visited a physician to consider RRT at approximately ≥ 3 months (175 [range, 87–365] days) prior to ESRD diagnosis requiring HD initiation.

Other reasons why physicians should refer patients with ESRD to a nephrology department are as follows: potential loss of appetite due to cytokine production, malabsorption due to gut edema, and difficulty in oral intake arising from general fatigue29. According to the 2020 KDOQI guidelines, CKD malnutrition care should be undertaken by multidisciplinary teams30. To evaluate the malnutrition status, GNRI was developed. Interestingly, previous studies have shown that it is useful for evaluating the mortality of patients with CKD8,9,17,19. One report stated that the GNRI was useful in predicting mortality in patients with CKD at the time of dialysis initiation19. Conversely, many studies have demonstrated that the GNRI could be an effective predictive marker in patients undergoing HD7,8,31. However, it remains unclear whether urgent HD initiation due to late referral and nutritional status is associated with patient outcomes. In our study, the emergent CVC insertion group had a lower visit frequency until HD initiation than the vascular access group and had lower GNRI scores, which has been recognized as a predictor of mortality. The fact that the CVC + low GNRI group had the lowest 3-year survival demonstrated that inappropriate patient evaluation or late referral to a nephrology department may lead to poor patient outcomes.

The major limitations of this study included the small patient cohort, the retrospective and short-term nature of the study, and the insufficient definition of the appropriate referral timing. Furthermore, factors that could not be measured and residual confounding factors might have affected our results. Indeed, we did not include tunneled-cuffed permanent CVC and compared the model performance of these nutritional indices with the malnutrition inflammation scores14, which is a standard nutritional assessment tool frequently used in patients undergoing HD. Additionally, we could not retrospectively examine the rationale behind the visit frequency affecting the GNRI scores. Further studies are needed to investigate the causes of the low number of visits in detail. GNRI is not only a nutritional score, but is also a well known surrogate marker for predicting the survival of patients with CKD7,8,18.. Therefore, a similar study has to be conducted among patients undergoing unplanned initiation. Finally, because patients undergoing HD visited different HD clinics as outpatients after discharge, we did not consider residual bias that could exist in each clinic’s management.

In conclusion, the combination of unplanned HD initiation with emergent CVC insertion and low GNRI scores with low nutritional status was significantly associated with poor patient outcomes. Although this study had some limitations, our results support the critical role of managing patients with CKD who require RRT during the preservation period. We strongly recommend that non-nephrology experts should refer such patients to the appropriate nephrology department to facilitate early management of CKD. However, patient outcomes in ESRD may not be strictly associated with one nutritional factor, and further studies should focus on a larger number of patients, with detailed nutritional information over longer follow-up periods.

Methods

This study was approved by the Osaka Medical and Pharmaceutical University ethics committee in accordance with institutional guidelines. The study conformed to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written Informed consent for participation was obtained from all the participants involved in the study.

Study population and clinical design

A total of 219 patients with ESRD, who had started HD at Osaka Medical and Pharmaceutical University Hospital between January 2016 and December 2019, were retrospectively enrolled in this study. These patients were referred to our department from clinics or other departments to consider RRT. Among these patients, 39 were excluded because of lack of clinical data or acute kidney injury, while 18 were also excluded because they had a medical history of pre-RRT. A total of 162 patients were finally included in this study and were divided into two groups based on whether HD initiation was emergent CVC insertion or prepared vascular access (Fig. 4).

Flowchart of patient selection. Out of 219 patients screened between January 2016 and December 2019, we excluded 39 because of the presence of acute kidney injury and lack of data. Ordinarily, patients are referred to our department from other departments or clinics to prepare for vascular access and HD initiation. Of the 162 patients, the CVC and vascular access groups contained 62 and 100 patients, respectively. CVC, central venous catheter; HD, hemodialysis.

In our institute, patients with CKD are generally referred to our department to select RRT options. In this cohort, the patients who underwent planned HD underwent vascular access surgery in our department, and HD was subsequently initiated depending on their general condition. Unplanned HD initiation was defined as dialysis initiation when access was not ready for use, patients required hospitalization, or dialysis was initiated with a modality that was not the one that was initially selected for the patient (e.g., CVC insertion)32. Here, CVC indicates that the patient needed emergent HD with a temporary non-cuffed double lumen catheter due to a progressed CKD condition. The first visit referred to the day on which patients had a consultation or were referred to our department, and the visit frequency was the time between the first visit and the first HD session.

The geriatric nutrition risk index

The GNRI scores were calculated from the patients’ serum albumin value and bodyweight using the following formula: GNRI = (14.89 × serum albumin [mg/dL]) + 41.7 × (bodyweight/ideal bodyweight)17. The bodyweight was measured in kg at the time of HD initiation and then, 1 month later. The ideal bodyweight was calculated from the patient’s height and a body mass index of 22 kg/m2. The GNRI scores were used as both continuous and categorical variables. Here, we adopted a GNRI score of 91.2 points as the cut-off for dividing the low and high GNRI groups in accordance with a previous study30,31.

Statistical analysis

Demographic information is summarized using frequency counts, means with standard deviations, or medians with interquartile ranges. The chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare categorical variables, and Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance was used to compare continuous variables, as appropriate. ROC curve analysis was used to investigate whether visit frequency values could distinguish between CVC insertion and non-insertion at HD initiation. The frequency with the best accuracy was selected as the cut-off value. A multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression model was used to assess risk factors for all-cause mortality. The 3-year survival rate was initially estimated using Kaplan–Meier analysis. The population of kidney transplantation after HD initiation was considered censored in the survival analysis. Univariate analysis was used to examine prognostic factors for the final multivariate Cox regression analysis model. Factors that reached significance in the univariate analysis were subsequently included in the multivariate Cox model to determine the independent effects of each factor. Two-sided p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All the statistical analyses were performed using JMP Software 15 Pro version (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Data availability

The data supporting this study's findings are available on request from the corresponding author (HA).

References

Foley, R. N. & Collins, A. J. End-stage renal disease in the United States: An update from the United States Renal Data System. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 18, 2644–2648 (2007).

Agarwal, R. Defining end-stage renal disease in clinical trials: A framework for adjudication. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 31, 864–867 (2016).

Roy, D., Chowdhury, A. R., Pande, S. & Kam, J. W. Evaluation of unplanned dialysis as a predictor of mortality in elderly dialysis patients: A retrospective data analysis. BMC Nephrol. 18, 364 (2017).

Ravani, P. et al. Associations between hemodialysis access type and clinical outcomes: A systematic review. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 24, 465–473 (2013).

Woo, K. & Lok, C. E. New insights into dialysis vascular access: What is the optimal vascular access type and timing of access creation in CKD and dialysis patients?. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 11, 1487–1494 (2016).

Baek, S. H. et al. Outcomes of predialysis nephrology care in elderly patients beginning to undergo dialysis. PLoS ONE 10, e0128715 (2015).

Spatola, L., Finazzi, S., Santostasi, S., Angelini, C. & Badalamenti, S. Geriatric nutritional risk index is predictive of subjective global assessment and dialysis malnutrition scores in elderly patients on hemodialysis. J. Ren. Nutr. 29, 438–443 (2019).

Xiong, J. et al. Association of geriatric nutritional risk index with mortality in hemodialysis patients: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 43, 1878–1889 (2018).

Yamada, S. et al. Geriatric nutritional risk index (GNRI) and creatinine index equally predict the risk of mortality in hemodialysis patients: J-DOPPS. Sci. Rep. 10, 5756 (2020).

Guarnieri, G., Antonione, R. & Biolo, G. Mechanisms of malnutrition in uremia. J. Ren. Nutr. 13, 153–157 (2003).

Carrero, J. J. et al. Global prevalence of protein-energy wasting in kidney disease: A meta-analysis of contemporary observational studies From the international Society of Renal Nutrition and Metabolism. J. Ren. Nutr. 28, 380–392 (2018).

Wei, K. et al. Association of frailty and malnutrition With long-term functional and mortality outcomes Among community-dwelling older adults: Results From the Singapore longitudinal aging Study 1. JAMA Netw. Open 1, e180650 (2018).

Pifer, T. B. et al. Mortality risk in hemodialysis patients and changes in nutritional indicators: DOPPS. Kidney Int. 62, 2238–2245 (2002).

Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Kopple, J. D., Block, G. & Humphreys, M. H. A malnutrition-inflammation score is correlated with morbidity and mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 38, 1251–1263 (2001).

Leavey, S. F. et al. Body mass index and mortality in “healthier” as compared with “sicker” haemodialysis patients: Results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 16, 2386–2394 (2001).

Honda, H. et al. Serum albumin, C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and fetuin a as predictors of malnutrition, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in patients with ESRD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 47, 139–148 (2006).

Bouillanne, O. et al. Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index: A new index for evaluating at-risk elderly medical patients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 82, 777–783 (2005).

Lin, T. Y. & Hung, S. C. Geriatric nutritional risk index is associated with unique health conditions and clinical outcomes in chronic kidney disease patients. Nutrients 11, 2769 (2019).

Tanaka, A., Inaguma, D., Shinjo, H., Murata, M. & Takeda, A. Relationship between mortality and Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI) at the time of dialysis initiation: A prospective multicenter cohort study. Ren. Replace. Ther. 3, 27 (2017).

Lok, C. E. et al. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for vascular access: 2019 update. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 75(Suppl 2), S1–S164 (2020).

Kukita, K. et al. 2011 update Japanese Society for Dialysis therapy guidelines of vascular access construction and repair for chronic hemodialysis. Ther. Apher. Dial. 19(Suppl 1), 1–39 (2015).

Metcalfe, W., Khan, I. H., Prescott, G. J., Simpson, K. & MacLeod, A. M. Can we improve early mortality in patients receiving renal replacement therapy?. Kidney Int. 57, 2539–2545 (2000).

Ko, G. J. et al. Vascular access placement and mortality in elderly incident hemodialysis patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 35, 503–511 (2020).

Allon, M. Vascular access for hemodialysis patients: New data should guide decision making. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 14, 954–961 (2019).

Schmidt, R. J., Domico, J. R., Sorkin, M. I. & Hobbs, G. Early referral and its impact on emergent first dialyses, health care costs, and outcome. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 32, 278–283 (1998).

Stack, A. G. Impact of timing of nephrology referral and pre-ESRD care on mortality risk among new ESRD patients in the United States. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 41, 310–318 (2003).

Dogan, E., Erkoc, R., Sayarlioglu, H., Durmus, A. & Topal, C. Effects of late referral to a nephrologist in patients with chronic renal failure. Nephrology 10, 516–519 (2005).

Foote, C. et al. Impact of estimated GFR reporting on late referral rates and practice patterns for end-stage kidney disease patients: A multilevel logistic regression analysis using the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry (ANZDATA). Am. J. Kidney Dis. 64, 359–366 (2014).

Sahathevan, S. et al. Understanding development of malnutrition in hemodialysis patients: A narrative review. Nutrients 12, 3147 (2020).

Ikizler, T. A. et al. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for nutrition in CKD: 2020 Update. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 76(Suppl 1), S1–S107 (2020).

Yamada, K. et al. Simplified nutritional screening tools for patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 87, 106–113 (2008).

Chan, C. T. et al. Dialysis initiation, modality choice, access, and prescription: Conclusions from a kidney disease: Improving global outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int. 96, 37–47 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the staff working at the Blood Purification Center for their highly skilled management of the patients. We also thank Editage (http://www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.M., T.F., D.K., and Y.Y. contributed equally to this work and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. T.M., S.T., Y.F., K.K., and H.U. performed and analyzed the experiments. M.K., H.H., T.I., and H.N. analyzed the data and helped prepare the manuscript. HA designed and supervised the experiments and wrote and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maenosono, R., Fukushima, T., Kobayashi, D. et al. Unplanned hemodialysis initiation and low geriatric nutritional risk index scores are associated with end-stage renal disease outcomes. Sci Rep 12, 11101 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14123-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14123-y

This article is cited by

-

Geriatric nutritional risk index as a prognostic factor in elderly patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a propensity score-matched study

International Urology and Nephrology (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.