Abstract

Most studies focusing on only one directional effect among cognitive health, physical function, and incontinence may miss potential paths. This study aimed to determine the pathway by analyzing the bidirectional effects of exposure (X) on outcome (Y) and explore the mediating effect (M) between X and Y. Secondary data analyses were performed in this study. The original data were collected from August to October 2013 in one VH in Tainan, Taiwan, and the final sample size was 144 older male veterans. Path analysis was performed to test the pathway sequence X → M → Y among the three outcome variables. Approximately 80% of the veterans were aged 81 or older, approximately 42% had a functional disability, 26% had cognitive impairment, and 20% had incontinence. The relationships between functional disability and incontinence and between functional disability and cognition impairment were bidirectional, and functional disability played a key mediating role in the relationship between cognitive impairment and incontinence. Physical more than cognitive training in order to improve or at least stabilize functional performance could be a way to prevent or reduce the process of developing incontinence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aging society is a worldwide concern, and the size of the elderly population in Taiwan continues to increase with the development of medical technology and health care delivery systems1. The growth of the elderly population has triggered increasing demand for long-term care and skilled nursing institutions. Additionally, approximately 50.9% of senior citizens in need of long-term care services are veterans, and these veterans requiring care account for 23.7% of the total population of senior veterans2. With the growing average life span and the increasing prevalence of degenerative and psychosocial diseases with age, providing care for veterans has a considerable impact on medical resources and the cost of care.

Geriatric symptoms are often multifactorial in etiology; in addition to age-related change in physical function, risk factors such as coexisting cognitive impairment3, functional disability4, and incontinence5 cause or contribute to health decline. Studies have examined the association between cognitive impairment and its related factors, such as functional disability6,7 and incontinence8,9. Furthermore, other studies on incontinence10,11 have found that declines in cognitive12 and physical function12,13 are noteworthy contributors to incontinence but have not confirmed the direction of the association. Although most literature has confirmed that any two of these three health factors may have a bidirectional association, the pathway between the three factors and whether there is a potential moderating or mediating effect between these three is unclear.

In order to improve the effectiveness of treatment, it is necessary to develop multimodal interventions, but first we need to understand the pathways between the health factors that affect aging. Therefore, this study decided to explore all possible relationships between cognitive impairment, disability, and incontinence to find out the aging pathways of veteran residents, and to determine the directional correlation between the three health factors through path analysis. This study explored the pathway sequence X → M → Y among the three domains and hypothesized that X (independent variable) has either a direct effect on Y (dependent variable) in addition to an indirect effect through M (mediator) or an indirect effect on Y through M. The objectives of the current study, therefore, were to explore (a) the direct effects of X on Y, (b) the interaction effect of X1* X2 on Y, and (c) the indirect effect of X on Y through M. Rather than focusing on only one directional effect, we adopted the exploratory analytical approach to examine all possible pathways.

Methods

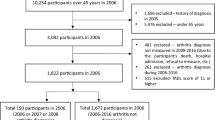

Study design, settings, and participants

This study performed secondary data analyses of a data set obtained from a cross-sectional study. The original study was based on one veterans’ home (VH) in Tainan, belonging to one of the tertiary veterans’ general hospital; Kaohsiung Veterans’ General Hospital, located in southern Taiwan. At the end of 2012, a total of 400 veterans were receiving personal care in VH in Tainan. All male residents living Tainan VH were invited for study and participants were enrolled if they agreed to participate. Those who were <aged 50, had altered consciousness, severe impairment in hearing or vision, and communication difficulties (N = 200) were excluded for study. To avoid interrater variability, one well-trained nurse collected the data between August and September 2013. In total, 200 residents 50 years of age or older were selected by a purposive sampling method; among them, 56 residents were excluded because of poor cognitive function or unwillingness to participate in this study, and 144 residents were interviewed (72%). This study was approved by the Human Experiment and Ethics Committee of Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital and adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Residents were interviewed after their informed consent was obtained (IRB No.: VGHKS13-CT6-03).

Measurements

Outcome variables: cognitive impairment, functional disability, and incontinence

Cognitive function was measured using the 10-item Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire; scores ranged from 0 to 10, with a higher score indicating poorer intellectual function14. Patients who made two errors or fewer were deemed cognitively intact, and those who made three or four errors were regarded as having mild cognitive impairment. Moderate impairment was defined as making five to seven errors, and severe impairment was defined as making eight to ten errors; the maximum number of errors possible was 10. Adjustments were made to scores regarding education: participants with less than a high school education were permitted one additional error, and those with more than a high school education were permitted one fewer errors14.

Measures of functional disability reflect limitations in performing independent living tasks, typically contain activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). A Chinese-translated version15 of the Barthel Activities of Daily Living (ADL) index16 was used to assess the current level of a participant’s ability for each of 10 items: feeding(10 points), grooming(5 points), toilet use(10 points), bathing(5 points), dressing(10 points), bowels(10 points), bladder(10 points), mobility(15 points), transfer(15 points), and stair climbing(10 points). Each activity was given a score corresponding to 2–4 levels of dependency ranging from 0 (unable to perform a task), 5, 10, to 15 (fully independent)17. Possible total scores ranged from 0 to 100 and were obtained by summing the points for each item, with higher scores indicating greater independence. In accordance with relevant studies, functional disability was categorized into five levels: fully independent (a score of 100), slight dependency (scores of 91–99), moderate dependency (scores of 61–90), severe dependency (scores of 21–60) and total dependency (scores of 0–20).

Incontinence data were determined from study subjects’ response to two questions regarding the veterans: “Does the resident have urinary incontinence?” and “Does the resident have fecal incontinence?” Incontinence was determined on the basis of an affirmative response (yes) to these questions, and incontinence severity was categorized into four levels according to responses (yes or no) to questions regarding the presence of the following conditions: regular urination and bowel movements, urinary incontinence only, fecal incontinence only, and urinary and fecal incontinence.

Control variables

Control factors were selected on the basis of measures of objective health in the study. Potential risk factors included demographic factors, comorbidities, and medication use. Participants’ age, education level, and marital status were recorded as demographic data. Physical disease was evaluated according to comorbidity of the 10 most common chronic diseases: hypertension, heart disease, urinary disease, diabetes, gastrointestinal disease, psychiatric symptoms, dementia, stroke, rheumatoid arthritis, and malignant tumors. Medication use was classified into four levels according to the number of medications patients regularly used among the 10 most common medications (zero, one, two, three, or four or more).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were determined for demographic characteristics, comorbidities, medication use, and health status. In addition, path analysis was adopted to examine the hypothesized interrelationships among cognitive impairment, functional disability, and incontinence; outcome variables were selected while controlling for important covariates18,19.

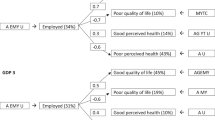

This study adopted a mediation model to test whether the relationship between X (Independent variable) and Y (dependent variable) is transmitted through the mediator (M) (Fig. 1). X, M, and Y represent cognitive impairment, functional disability, and incontinence, respectively. In doing so, this study made three assumptions: (a) X and Y have bidirectional effect (b) X has a direct effect on Y in addition to an indirect effect through M and (c) X has an indirect effect on Y through M. According to the research hypotheses, the following were examined: (a) the direct predictive effect of independent variable (X) on dependent variable (Y), (b) the interaction effect of independent variables (X1 * X2) on dependent variable (Y), and (c) the indirect effect of independent variable (X) on dependent variable (Y) through mediator (M).

Research design and procedure of the exploratory model. Path diagram for testing direct and indirect effects (note: X = independent variable, Y = dependent variable, and M = mediating variable). The testing procedure scheme followed three steps. Complete mediation model illustrating that all of the relationships between X and Y are transmitted through the mediator (disability).

For each model, demographic factors, comorbidities, and medication use were adjusted. To test the mediating processes, the bootstrap method was adopted to test direct and indirect effects for the structural models20. Goodness of fit was determined according to the value of chi-square value (CMIN/DF ≦ 3), comparative fit index (CFI ≧ 0.90), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI ≧ 0.90), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.08), and p-value for GOF > 0.05, as recommended by Hu and Bentler21 and McDonald22. Furthermore, parameter values were estimated with a maximum likelihood model using IBM AMOS and data were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS)22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

A total of 144 participants completed the questionnaire and were included in the final analysis. The patients’ distribution of all study variables is summarized in Table 1. Approximately 80% of the patients were aged 81 or older, 40% were married, only 9% had no formal education, and less than 8% were not taken medication. The majority of veterans were diagnosed with at least one comorbid disease (97.2%). In addition, approximately 42.4% had a functional disability, 27.8% had cognitive impairment, and 22.2% had incontinence.

Pathway model estimation

Figure 1 presents the conceptual model. First, we test a hypothesized bidirectional effect between X and Y (β11&β12, β13&β14, β15&β16) (Model A). Second, the interaction effect between X1 and X2 was further test with Y (β23, β26, β29) (Model B). Third, we verify the mediating effect between X1 and X2 with Y, to find out how X affects Y through M (mediation variables) (β31& β32, β33& β34) (Model C). Within the associations among cognitive impairment, functional disability, and incontinence, the potential associated factors were also adjusted. Table 2 presents the three models with 19 path diagrams, in addition to the interaction effect, the regression coefficients for disability consistently showed a significant association with incontinence and cognitive impairment.

Bidirectional effect model (Model A)

We constructed six models (A1–A6) based on different combinations of three outcome variables and tested the effect between X and Y (X ↹ Y bidirectional association). The results revealed that there were significant effects between functional disability and incontinence (in A3 and A4), followed by cognitive impairment and functional disability (in A5 and A6). In addition to cognitive impairment and incontinence, these findings indicate that these outcome variables affect each other, in particular a relatively strong bidirectional association between functional disability and incontinence with very significant levels (Table 2).

Interaction effect model (Model B)

We further tested the interaction effect of X2 on the relationship between X1 and Y. X2 is a moderator variable if an interaction exists between X1 (predictor or independent variable) and X2 (moderating variable) that affects Y. The results of model B (B1-B3) revealed that the interactions were not significant (β23, β26, β29) (p > 0.05); the effects only existed between disability to incontinence (β21 in B1), cognitive impairment to functional disability (β24 in B2), incontinence to functional disability (β25 in B2), and disability to cognitive impairment (β28 in B3). The results of this analysis did not indicate the existence of a moderating effect (Table 2).

Mediation effect model (Model C)

Model A and Model B have demonstrated no direct or moderating link between cognition and incontinence. To improve the model, we further tested the mediating effect in model C (C1-C2), and the results provide evidence of complete mediation (X → M → Y): cognitive impairment affected functional disability (β31), which in turn affected incontinence (β32) (in C1); incontinence affected functional disability (β33), which in turn affected cognitive impairment (β34) (in C2) (Table 2). The best model fit was found in the mediation model C1, adjusting for the mediation effect between incontinence to disability (Model fit: Chi-square = 1.371). The strong effect was found between functional disability to incontinence (β32 = 0.752), followed by incontinence to functional disability (β33 = 0.648), disability to cognitive impairment (β34 = 0.314), and cognitive impairment to disability (β31 = 0.176). Accordingly, disability can not only independently and significantly affect cognitive impairment and incontinence, also through cognitive impairment (incontinence) to affect incontinence (cognitive impairment). This suggests that all of the relationships between X and Y are transmitted through the mediator (Table 2).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the interrelationship among cognitive impairment, functional disability, and incontinence by using a path analysis model. Our findings indicate that older patients’ health after institution is a complex process, with three domains (cognitive impairment, functional disability, and incontinence) often simultaneously influencing each other. Two points are of interest. First, bidirectional effects have been demonstrated in disability-cognitive impairment and disability-incontinence. Second, cognitive impairment correlated with incontinence may mediate through the functional disability.

Our research findings were consistent with those of other studies that have found bidirectional relationships between cognitive impairment and functional disability6,7,23. Furthermore, a meta-analysis study24 found that physical functioning was a more consistent predictor of cognitive change than cognitive change was of physical functioning; this is in agreement with the findings of our study because stronger impacts were identified in most models. The strong association between functional disability and cognitive impairment may be unsurprising, given that functional disability is required to make a diagnosis of dementia. The findings suggest that early detection of functional disability is crucial, and physical activity is recommended for older adults with normal cognition to reduce the risk of cognitive decline.

An association between functional disability and incontinence among older people was previously described11,25,26. In fact, awareness of greater functional disability may cause incontinence as a physiological reaction to the loss of functioning. Studies have shown that decline in physical function, particularly impairment of mobility and lower body strength, is an important risk factor for the development of urinary incontinence frequency27,28. This association can be a direct consequence of the inability of getting to the toilet and removing clothes before losing urine. Thus, it is possible that the relationship between physical performance and incontinence is bidirectional29, generating a vicious cycle where the reduction of physical performance causes an increase in cases of incontinence and incontinence causes a reduction in physical performance. Strategies such as prompted voiding and individual physical training have been shown to have a positive effect to reduce the frequency of incontinence episodes and improve mobility endurance25,30,31.

In our data, the effect of cognitive impairment on incontinence was mainly explained by the significant mediator of functional disability. A cross-sectional study showed that more severe urinary incontinence (UI) was associated with more ADL impairment, and nursing home residents with UI had poor cognitive impairments, and a higher incidence of urinary tract infections32. As deteriorated functional disability may be an early sign rather than other risk factor for incontinence, the temporal relation between functional disability and incontinence in older veterans needs to be further tested. Nevertheless, the presence of cognitive impairment may negatively impact older patients’ subsequent functional disability and incontinence by decreasing their motivation to maintain healthy and self-care behaviors such as physical rehabilitation and engaging in role activities. Treating one condition might improve another so targeting this triad with a multimodal intervention along with necessary pharmacological therapy might not only more effectively treat incontinence but also improve overall function and cognition in older adults following an institution for medical and long-term services.

In this study, the interaction terms were not statistically significant. Since the statistical power of tests of interaction terms is drawn not from the entire sample size but from the size of the smallest of the intersecting groups it represents. About a quarter of our samples had cognitive impairment (28%) or incontinence (22%). The non-significant results of this interaction analysis might indicate that this group is highly homogeneous. Furthermore, regardless of cognitive impairment, the proportion of incontinence is similar (10–12%), which is different from other literatures. A current study found significant differences in the urinary tract between residents with and without dementia, showing that the prevalence of UI is very high even in early dementia (64%), reaching 94% in severe dementia33. Additional consideration of severity of cognitive impairment and of multicollinearity between cognitive impairment and incontinence would help determine the exact contribution of a cognitive impairment to risk of incontinence.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the pathways associated with cognitive impairment, functional disability, and incontinence in male veterans. In this study, no hypothesized direction of paths among three outcome variables was specified first. This exploratory approach could be strengths to provide new information of direct and indirect effects to fill knowledge gap. The dataset for this study allowed us to explore all possible associations among all three variables of interest in order to design the best intervention or treatment for the health degradation of this group.

This study had several limitations. First, its cross-sectional design limited the interpretation of risk factor associations. Although this study approach suggests the existence of a bidirectional link, it was only able to prove direct and indirect associations and not causation. There are debates as whether cognitive impairment should affect incontinence in this model rather than the direction we have found. Clearly, all three domains have complex etiologies and are interacted and we could not rule out the reverse paths in the validation analyses. In addition, given that our study design was observational, causal interpretations in this regard are limited. Second, clinical assessments cannot be performed to identify incontinence, and because of self-reporting incontinence assessment, the disease may be underreported. In order to reduce the validity and reliability issues that self-reported data may cause, we have trained nurses to collect self-reported incontinence information, and further verified the collected data with the agency’s responsible nurse. Third, the self-reported information of medication use could be incomplete as the presence of chronic conditions. The common chronic conditions listed account for 91.7% of the total conditions, and 70% of the commonly used medications listed are for these common conditions. Considering that residents with multiple diseases use more than one medication, the “quantity of medication usage” is used in the measurement. Therefore, even if the amount of medication used by some residents may be underestimated, it should not affect the results. Finally, the generalizability of the present findings is also limited by a small sample size recruited from a single VH residence. To reduce the potential factors that may confound the interrelationship, many potential risk factors, such as multimorbidity and medication use, were adjusted in the model.

Conclusions

This study observed that functional disability was prevalent and strongly associated with incontinence and cognitive functions. Although the direct and indirect relationships between variables are substantiated in the proposed model, in the validation analyses when the alterative models were tested, we found evidence in favor of a bidirectional correlation. In addition, these pathways suggest a mediating relationship among cognitive impairment, functional disability, and incontinence in male veterans and that preventing functional disability can improve cognitive impairment and incontinence during the post-institution phase. The findings support its mediating effect and merit further corroboration. Future studies should examine the mechanisms underlying the onset timing of each condition, the identification of which is crucial for developing interventions and exploring their optimal timing to maintain optimal physical function and reduce subsequent health decline.

Data availability

We were given permission to use the data from the Veterans study (Grant 102-FI-GHC-IAC-R-002) by the Human Experiment and Ethics Committee of Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital. The datasets used for this analysis are not publicly available, as the use of data from the Veterans study requires the permission of the KVGH committee.

References

Ministry of the Interior. (ed. Annual Statistics of Internal Affairs) (Ministry of the Interior, Taiwan (2018).

Veterans Affairs Council Republic of China. (Veterans Affairs Council Republic of China, ISSN: 2074-4846, Taipei (2017).

Sachdev, P. S. et al. The prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in diverse geographical and ethnocultural regions: The COSMIC Collaboration. PLoS ONE. 10, e0142388, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0142388 (2015).

He, W. & Larsen, L. J. Older Americans With a Disability: 2008–2012. (U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC (2014).

Thirugnanasothy, S. Managing urinary incontinence in older people. BMJ. 341, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c3835 (2010).

Dotchin, C. L. et al. The association between disability and cognitive impairment in an elderly Tanzanian population. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health. 5, 57–64, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jegh.2014.09.004 (2015).

Shimada, H. et al. Cognitive impairment and disability in older Japanese adults. PLoS One. 11, e0158720, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158720 (2016).

Coppola, L. et al. Urinary incontinence in the elderly: relation to cognitive and motor function. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 35, 27–34 (2002).

Hatta, T., Iwahara, A., Ito, E., Hatta, T. & Hamajima, N. The relation between cognitive function and UI in healthy, community-dwelling, middle-aged and elderly people. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 53, 220–224, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2010.11.020 (2011).

Erekson, E. A. et al. Functional disability and compromised mobility among older women with urinary incontinence. Female Pelvic. Med. Reconstr. Surg. 21, 170–175, https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000000136. (2015).

Erekson, E. A. et al. Functional disability among older women with fecal incontinence. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 212(327), e321–327, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2014.10.015 (2015).

Huang, A. J., Brown, J. S., Thom, D. H., Fink, H. A. & Yaffe, K. Urinary Incontinence in Older Community-Dwelling Women: The Role of Cognitive and Physical Function Decline. Obstet. Gynecol. 109, 909–916, https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000258277.01497.4b (2007).

Nuotio, M., Luukkaala, T., Tammela, T. L. J. & Jylhä, M. Six-year follow-up and predictors of urgency-associated urinary incontinence and bowel symptoms among the oldest old: A population-based study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriat. 49, e85–e90 (2009).

Pfeiffer, E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 23, 433–441 (1975).

Leung, S. O., Chan, C. C. & Shah, S. Development of a Chinese version of the Modified Barthel Index–validity and reliability. Clin. Rehabil. 21, 912–922 (2007).

Mahoney, F. I. & Barthel, D. Functional evaluation: The Barthel Index. Md. State. Med. J. 14, 56–61 (1965).

Wade, D. T. & Collin, C. The Barthel ADL Index: a standard measure of physical disability? Int. Disabil. Stud. 10, 64–67 (1988).

Byrne, B. M. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. (2001).

Kline, R. B. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling(2nd ed). (Guilford Press (2005).

Shrout, P. E. & Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods. 7, 422–445 (2002).

Bagshaw, S. M. et al. Association between frailty and short- and long-term outcomes among critically ill patients: a multicentre prospective cohort study. CMAJ. 186, E95–102, https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.130639 (2014).

McDonald, R. P. & Ho, M.-H. R. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol. Methods. 7, 64–82, https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.64 (2002).

Taniguchi, Y., Yoshida, H., Fujiwara, Y., Motohashi, Y. & Shinkai, S. A prospective study of gait performance and subsequent cognitive decline in a general population of older Japanese. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 67, 796–803 (2012).

Clouston, S. A. et al. The dynamic relationship between physical function and cognition in longitudinal aging cohorts. Epidemiol. Rev. 35, 33–50 (2013).

Schumpf, L. F. et al. Urinary incontinence and its association with functional physical and cognitive health among female nursing home residents in Switzerland. BMC Geriatr. 17, 17–17, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0414-7 (2017).

Kafri, R., Shames, J., Golomb, J. & Melzer, I. Self-report function and disability: a comparison between women with and without urgency urinary incontinence. Disabil. Rehabil. 34, 1699–1705 (2012).

Suskind, A. M. et al. Urinary Incontinence in Older Women: The Role of Body Composition and Muscle Strength: From the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 65, 42–50, https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14545 (2017).

Chiu, A. F., Huang, M. H., Hsu, M. H., Liu, J. L. & Chiu, J. F. Association of urinary incontinence with impaired functional status among older people living in a long-term care setting. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 15, 296–301, https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12272 (2015).

Corrêa, L. Cd. A. C. et al. Urinary Incontinence Is Associated With Physical Performance Decline in Community-Dwelling Older Women: Results From the International Mobility in Aging Study. J. Aging Health. 31, 1872–1891, https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264318799223 (2019).

Ouslander, J. G., Ai-Samarrai, N. & Schnelle, J. F. Prompted voiding for nighttime incontinence in nursing homes: is it effective? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 49, 706–709, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49145.x (2001).

Fink, H. A., Taylor, B. C., Tacklind, J. W., Rutks, I. R. & Wilt, T. J. Treatment interventions in nursing home residents with urinary incontinence: a systematic review of randomized trials. Mayo Clin. Proc. 83, 1332–1343, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0025-6196(11)60781-7 (2008).

Jumadilova, Z., Zyczynski, T., Paul, B. & Narayanan, S. Urinary incontinence in the nursing home: resident characteristics and prevalence of drug treatment. AJMC. 11, S112–120 (2005).

Schussler, S., Dassen, T. & Lohrmann, C. Care dependency and nursing care problems in nursing home residents with and without dementia: a cross-sectional study. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 28, 973–982, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-014-0298-8 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital Pingtung Branch (grant number: 102-FI-GHC-IAC-R-002). This work thanks the staff and participants in Tainan VH who greatly assisted in this research by helping to complete the original data collection. This work was supported by Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital Pingtung Branch (grant number: 102-FI-GHC-IAC-R-002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: Su Y.Y. and Chen C.M. Acquisition of data: Tsai Y.Y., Lin C.C., Su Y.Y. Analysis and interpretation of data: Chen C.M., Chu C.L., Su Y.Y. Drafting of the manuscript: Chen C.M. and Su Y.Y. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Chu C.L., Tsai Y.Y., Lin C.C. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, YY., Tsai, YY., Chu, CL. et al. Exploring a Path Model of Cognitive Impairment, Functional Disability, and Incontinence Among Male Veteran Home Residents in Southern Taiwan. Sci Rep 10, 5553 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62477-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62477-y

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.