Abstract

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated an increased risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Therefore, we investigated the risk of extrahepatic malignancies associated with HCV infection. Inpatients diagnosed with lymphoma, breast, thyroid, kidney, or pancreatic cancer (research group, n = 17,925) as well as inpatients with no malignancies (control group, n = 16,580) matched by gender and age were enrolled from The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University between January 2008 and December 2016. A case-control study was conducted by retrospective analysis. The difference in HCV prevalence was analyzed between the research group and the control group. Also, the research group was compared to the 2006 National Hepatitis C sero-survey in China. A total of 86 cases were positive for anti-HCV in the research group. Compared with the control group (103 cases were anti-HCV positive), no significant associations between extrahepatic malignancies and HCV infection were observed. Meanwhile, compared to the 2006 National Hepatitis C sero-survey, we observed a significant association between the chronic lymphoma leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) and HCV seropositivity in females in the research group aged 1–59 years old (OR = 14.69; 95% CI, 1.94–111.01). HCV infection had a potential association with CLL/SLL in females aged 1–59 years old. Our study did not confirm an association between HCV infection and the risk of extrahepatic malignancies. In regions with a low HCV prevalence, the association between HCV infection and extrahepatic malignancies needs further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a leading cause of liver-related mortality worldwide. Recent estimates have shown an increase in its seroprevalence over the last decade to 2.8%, with almost 185 million infections worldwide1. One-third of chronic HCV infections may progress to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)2. Meanwhile, nearly 350,000 patients will die from HCV-related complications3. The HCV prevalence rate differs in different geographical regions, ranging from 1.20% in low-prevalence regions such as Latin America to 3.80% in high-prevalence regions such as the Middle East4. In China, the results of the Chinese National HCV serum prevalence survey in 2006 showed that the prevalence of anti-HCV was 0.43% in those aged 1–59 years old, which represents up to 10 million patients5,6.

Currently, cancer is among the top four causes of human mortality7. In a global epidemiological investigation, de Martel et al. found that 2 million cases (16%) of 12.7 million newly diagnosed cancer cases were attributed to exposure to infectious agents, with a higher rate recorded in developing countries8. HCC is the second leading cause of site-specific cancer-related death worldwide. In addition, HCV infection contributes to 80% of HCC cases9. Although HCV is a hepatotropic virus, several studies have shown that HCV may infect organs and tissues other than the liver, including peripheral blood cells, kidney, skin, oral mucosa, salivary glands, pancreatic tissues, heart, gallbladder, intestine, and adrenal gland tissues10,11,12,13,14,15. Moreover, HCV infection has been implicated in extrahepatic malignancies such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), cholangiocarcinoma, pancreatic cancer, and oral carcinomas16,17,18,19. However, the association between HCV infection and extrahepatic malignancies among the Chinese population has not been investigated in depth. Thus, the aim of this study was to address this issue.

Materials and Methods

Study population and methods

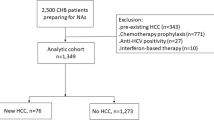

We conducted a case-control study by retrospective analysis. Inpatients diagnosed with lymphoma, breast, thyroid, kidney, or pancreatic cancer as well as cancer-free inpatients (control group) were enrolled at The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University from January 2008 to December 2016. The different malignancies were confirmed by pathological and histological examination. Accordingly, 17,925 patients were diagnosed with the above-mentioned extrahepatic malignancies. Next, all participants were screened for HCV infection as well as possible hepatitis B virus (HBV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infections. Participants with mixed infections (positive for anti-HCV antibodies as well as anti-HBV, anti-HIV, anti-CMV, and/or anti-EBV) were excluded (screening process seen Fig. 1).

Patients enrolled in the cancer group (research group) and the control group were matched for gender, age, and calendar year of selection by a ratio of 1:1. The different prevalence of anti-HCV seropositivity was analyzed between the research group (cancer patients) and the control group. Meanwhile, the data of the research group were compared to the data from the 2006 National Hepatitis C sero-survey in China. Lymphoma patients were classified for subtype-specific analysis using the World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues20. In this study, access to the patients’ data was approved by The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University Ethics Committee.An informed consent was obtained from all participants after an explanation of the protocol.

Detection of viral index and definition of HCV infection

HBsAg, anti-HCV, and anti-HIV were detected by ELISA kits obtained from InTec Products, Inc., Xiamen, China. Patients with HCV seropositivity were defined as those with positive HCV antibodies. Anti-CMV and anti-EBV were detected by ELISA kits obtained from Beijing Baer Bioengineering Co., Ltd. and European Mongolian Medical Diagnostics (China) Co., Ltd., respectively.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed by IBM SPSS, version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). The mean and standard deviation were calculated for continuous variables with a normal distribution. The median (quartile) was calculated for continuous variables with a non-normal distribution. The chi-squared test was used to calculate the prevalence of anti-HCV seropositivity between the research group and the control group. The odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were also measured to evaluate the association between HCV prevalence and the risk of extrahepatic malignancies. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of patients with extrahepatic malignancies

Among 16,580 patients with extrahepatic malignancies, there were 4593 males (27.73%) and 11,983 females (72.27%). The average patient age was 51 (SD = 15) years old. The 16,580 cancer-free participants (control group) had the same demographic characteristics in terms of age and gender due to the 1:1 matching ratio. The majority of patients with lymphoma, kidney cancer, or pancreatic cancer were males (59.39%, 64.10%, and 59.34%, respectively), and most of the patients with breast cancer or thyroid cancer were females (99.36% and 77.13%, respectively). The age ranges of patients with lymphoma, breast cancer, thyroid cancer, kidney cancer, or pancreatic cancer were 3–92 years old, 12–96 years old, 6–84 years old, 3–99 years old, and 6–92 years old, respectively. The mean age of patients with pancreatic cancer was the oldest, while the mean age of thyroid cancer patients was the youngest. In addition, the mean age of the lymphoma, breast cancer, and kidney cancer patients was around 50 years old (Table 1).

During the nine consecutive years of this study, the number of cancer patients grew exponentially, especially for breast cancer and thyroid cancer patients. The number of patients with breast cancer increased from 359 in 2008 to 1272 in 2016, while the number of patients with thyroid cancer increased from 173 in 2008 to 1014 in 2016, as reported in Supplementary Fig. S1. The age of patients with extrahepatic malignancies had a normal distribution trend, as reported in supplementary Fig. S2. The peak age was 41–50 years old for patients with breast cancer or thyroid cancer (33.88% and 26.87%, respectively), while the peak age was 51–60 years old for patients with lymphoma or kidney cancer (24.74% and 25.95%, respectively). In contrast, the peak age of patients with pancreatic cancer was the oldest (61–70 years old, 34.40%).

Comparisons of anti-HCV seropositivity between the research group and the control group

Among patients of both the research group and the control group, we observed that a total of 189 patients were positive for anti-HCV, 86 in the research group and 103 in the control group. Compared to the control group, the HCV prevalence was not higher in patients with extrahepatic malignancies (Table 2). In a subtype-specific analysis for lymphoma20, the HCV prevalence in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) (1.69%) was higher than that in patients with NHL (0.69%). The most common subtype of NHL was B-cell lymphoma. The most common types of B-cell NHL were diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL; 60.80%), follicular lymphoma (FL; 12.24%), and mantle cell lymphoma (7.70%). The HCV prevalence among patients with chronic lymphoma leukemia (CLL)/small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) was the highest (1.44%) among the B-cell NHLs. Overall, HCV-seropositivity was not significantly associated with any subtype of lymphoma (Table 3). Furthermore, we conducted a subanalysis according to the sex distribution among patients aged 1–59 with extrahepatic malignancies. Compared to the national HCV sero-survey5, the prevalence of HCV was higher in female patients with CLL/SLL (5.56%), with a significant association between HCV-seropositivity and CLL/SLL (OR = 14.69, 95% CI: 1.94–111.01, P = 0.001). On the other hand, we did not find significant associations between HCV-seropositivity and other subtypes of lymphoma (Table 4).

Discussion

The association between HCV infection and lymphoma, especially B-cell lymphoma of NHL, is the most studied subject in terms of HCV infection and extrahepatic malignancies21,22,23. In regions with a high HCV prevalence such as Southern Europe, including Italy and Spain, as well as Asian countries like Japan, HCV infection was obviously related to NHL24,25. However, in regions with a low HCV prevalence such as France and Canada, the association was not significant26. To date, in order to clarify the association between HCV infection and NHL, seven systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses have been published22,23,27,28,29,30,31. These analyses contained a total of 131 studies and five meta analyses, and they confirmed a significant association (OR range: 2–4). On the other hand, two analyses reported different results, especially when the subanalysis was performed according to region and race23,29. Meanwhile, HCV infection was only related to some subtypes of B-cell NHL such as DLBCL and marginal zone lymphoma23. Therefore, accumulating evidence has confirmed an association between HCV infection and NHL. However, there is no association for different regions, races, or subtypes of NHL.

In the current study, only 21 patients were positive for anti-HCV among 2785 patients with lymphoma. The prevalence of HCV was only 0.69% in NHL patients, which is even lower than that in patients with HL (1.69%). Although there were no significant differences for the prevalence of HCV between all five extrahepatic malignancies, including the main subtypes of lymphoma, and the national sero-HCV survey in men, the prevalence of HCV in CLL/SLL was significantly higher (5.56%) in females than in the corresponding control group from the national survey. Taken together, although this study did not confirm an association between HCV infection and most subtypes of NHL, female patients aged 1–59 years old with CLL/SLL had a higher prevalence of HCV infection (5.56%) than that from the national survey. Similarly, another recent Chinese study by Xiong et al. did not find a significant association between HCV infection and the main subtypes of lymphoma, except for splenic marginal zone lymphoma (SMZL), compared to the national sero-HCV survey32. It is important to note that although the subjects involved in the current study were matched for sex and age. However, we could not obtain detailed data from the national participants, especially for age-related information. This might have impacted the efficiency of our comparison; in particular, the peak of lymphoma showed an age-specific trend. In addition, there was only one CLL/SLL patient with positive anti-HCV, thus making it difficult to draw a solid conclusion.

Several studies have investigated the association between HCV infection and breast, thyroid, kidney, and pancreatic cancers in other countries18,33,34,35. Bruno et al. observed that some patients with HCC and anti-HCV positivity developed secondary cancers such as breast cancer36. However, later studies did not confirm such a significant correlation between HCV infection and breast cancer33,37. In addition, several research groups investigated the association between HCV infection and thyroid cancer, but the results are conflicting. Montella et al. and Antonelli et al. confirmed the presence of a significant assosiation, while Duberg et al. and Giordano et al. did not observe the same association38,39,40,41. In 2016, a meta-analysis by Wijarnpreecha et al.35 reported a significantly increased risk of kidney cancer among participants with HCV infection, with a RR of 1.86 (95% CI: 1.11–3.11). A major limitation in the meta-analysis by Wijarnpreecha et al. was the presence of significant heterogeneity between studies. Similarly, the association between HCV infection and pancreatic cancer is controversial as well18,42,43. With the exception to pancreatic cancer, limited information is available for the association between HCV infection and extrahepatic malignancies in China44. In this study, our results indicated that there was no significant association between HCV infection and breast, thyroid, kidney, as well as pancreatic cancers compared to the control group or the national sero-HCV survey.

The mechanism of HCV infection-induced NHL has been studied extensively. Upon treatment of HCV-infected lymphoma patients with interferon combined with ribavirin, lymphoma showed complete or partial regression45,46. A systematic review showed that 75% of those with lymphoproliferative disease and HCV infection could get complete regression after antiviral treatment47. Experimental research has explained HCV infection-induced NHL by three different mechanisms. De Re et al. have proposed that chronic antigen stimulation boosts B cell continuous reproduction48. Alternatively, the close attachment of envelope 2 protein of HCV to the CD81 receptor of B cells leads to polyclonal induction of immature CD27-B cells49. Finally, HCV infects B cells directly and is continuously replicated, resulting in gene mutation rearrangement, thereby promoting the abnormal clonal proliferation of B cells50.

In this study, we investigated the association between HCV infection and extrahepatic malignancies. However, our study had a few limitations that need to be addressed in future research. First, the research data were collected only from a single center; therefore, the results need to be confirmed by future multicenter studies. Second, this was a retrospective case-control study; thus, we could not provide a definite causal relationship between HCV infection and extrahepatic malignancies. Third, although age and sex were matched by a 1:1 ratio, other factors such as family history, environmental factors, and occupational factors were not considered.

In conclusion, compared to the control group, our case-control study did not confirm a significant association between HCV infection and the risk of lymphoma, including subtypes of lymphoma. However, HCV infection was significantly associated with CLL/SLL in females aged 1–59 years old, compared with controls from the national sero-HCV survey. On the other hand, our study did not find any significant association between HCV infection and the risk of other extrahepatic malignancies, including breast, kidney, and thyroid cancers. Therefore, in regions with a low HCV prevalence, the association between HCV infection and the risk of extrahepatic malignancies should be further studied in the future.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mohd Hanafiah, K., Groeger, J., Flaxman, A. D. & Wiersma, S. T. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology 57, 1333–1342 (2013).

Ly, K. N. et al. The increasing burden of mortality from viral hepatitis in the United States between 1999 and 2007. Ann. Intern. Med. 156, 271–8 (2012).

Lavanchy, D. The global burden of hepatitis C. Liver. Int. 29(Suppl 1), S74–81 (2009).

Mohd Hanafah, K. et al. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology 57, 1333–42 (2013).

Chen, Y. S. et al. A sero-epidemiological study on hepatitis C in China. Chin. J. Epidemioi. 32, 888–891 (2011).

Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Medical association; Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Medical association. The guideline of prevention and treatment for hepatitis C:a 2015 update. Chin. J. Hepatol. 23, 906–923 (2015).

Pesec, M. & Sherertz, T. Global health from a cancer care perspective. Future Oncol. 11, 2235–45 (2015).

de Martel, C. et al. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 13, 607e15 (2012).

Vedham, V., Verma, M. & Mahabir, S. Early-life exposures to infectious agents and later cancer development. Cancer Med. 4, 1908–22 (2015).

Crovatto, M. et al. Peripheral blood neutrophils from hepatitis C virusinfected patients are replication sites of the virus. Haematologica 85, 356–361 (2000).

Sansonno, D. et al. Hepatitis C virus RNA and core protein in kidney glomerular and tubular structures isolated with laser capture microdissection. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 140, 498–506 (2005).

Kurokawa, M. et al. Analysis of hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA in the lesions of lichen planus in patients with chronic hepatitis C: detection of anti-genomic- as well as genomic-strand HCV RNAs in lichen planus lesions. J. Dermatol. Sci. 32, 65–70 (2003).

Carrozzo, M. et al. Molecular evidence that the hepatitis C virus replicates in the oral mucosa. J. Hepatol. 37, 364–369 (2002).

Toussirot, E. et al. Presence of hepatitis C virus RNA in the salivary glands of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome and hepatitis C virus infection. J. Rheumatol. 29, 2382–2385 (2002).

Yan, F. M. et al. Hepatitis C virus may infect extrahepatic tissues in patients with hepatitis C. World J. Gastroenterol. 6, 805–811 (2000).

Iqbal, T., Mahale, P., Turturro, F., Kyvernitakis, A. & Torres, H. A. Prevalence and association of hepatitis C virus infection with different types of lymphoma. Int. J. Cancer 138, 1035–7 (2016).

Palmer, W. C. & Patel, T. Are common factors involved in the pathogenesis of primary liver cancers? A meta-analysis of risk factors for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 57, 69–76 (2012).

Xu, J. H. et al. Hepatitis B or C viral infection and risk of pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. World J. Gastroenterol. 19, 4234–41 (2013).

Su, F. H. et al. Positive association between hepatitis C infection and oral cavity cancer: a nationwide population-based cohort study in Taiwan. PLoS One 7, e48109 (2012).

Swerdlow, S. H. et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC): Lyon. 439 (2008).

Peveling-Oberhag, J., Arcaini, L., Hansmann, M. L. & Zeuzem, S. Hepatitis C-associated B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Epidemiology, molecular signature and clinical management. J. Hepatol. 59, 169–77 (2013).

Dal Maso, L. & Franceschi, S. Hepatitis C virus and risk of lymphoma and other lymphoid neoplasms: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 15, 2078–85 (2006).

de Sanjose, S. et al. Hepatitis C and non-Hodgkin lymphoma among 4784 cases and 6269 controls from the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6, 451–8 (2008).

Zuckerman, E. et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Ann. Intern. Med. 127, 423–428 (1997).

Taborelli, M. et al. Hepatitis B and C viruses and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a case-control study in Italy. Infect. Agent. Cancer 11, 27 (2016).

Tkoub, E. M., Haioun, C., Pawlotsky, J. M., Dhumeaux, D. & Delchier, J. C. Chronic hepatitis C virus and gastric MALT lymphoma. Blood 91, 360 (1998).

Gisbert, J. P., García-Buey, L., Pajares, J. M. & Moreno-Otero, R. Prevalence of Hepatitis C Virus Infection in B-Cell Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology 125, 1723–32 (2003).

Matsuo, K. et al. Effect of hepatitis C virus infection on the risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Cancer Science 95, 745–752 (2004).

Negri, E., Little, D., Boiocchi, M., La Vecchia, C. & Franceschi, S. B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review. International Journal of Cancer 111, 1–8 (2004).

Libra, M. et al. Extrahepatic disorders of HCV infection: a distinct entity of B-cell neoplasia? Int. J. Oncol. 36, 1331–40 (2010).

Masarone, M. & Persico, M. Hepatitis C virus infection and non-hepatocellular malignancies in the DAA era: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Liver Int. 39, 1292–1306 (2019).

Xiong, W. et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C viral infections in various subtypes of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: confirmation of the association with splenic marginal zone lymphoma. Blood Cancer Journal 7, e548 (2017).

Larrey, D., Bozonnat, M. C., Kain, I., Pageaux, G. P. & Assenat, E. Is chronic hepatitis C virus infection a risk factor for breast cancer? World J. Gastroenterol. 16, 3687–91 (2010).

Wang, P. et al. Hepatitis C virus infection and risk of thyroid cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arab J. Gastroenterol. 18, 1–5 (2017).

Wijarnpreecha, K. et al. Hepatitis C infection and renal cell carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Gastrointest. Pathophysiol. 7, 314–319 (2016).

Bruno, G., Andreozzi, P., Graf, U. & Santangelo, G. Hepatitis C virus: a high risk factor for a second primary malignancy besides hepatocellular carcinoma. Fact or fiction? Clin. Ter. 150, 413–8 (1999).

Hwang, J. P. et al. Hepatitis C virus screening in patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy. J. Oncol. Pract. 10, e167–74 (2014).

Montella, M. et al. Risk of thyroid cancer and high prevalence of hepatitis C virus. Oncol. Rep. 10, 133–6 (2003).

Antonelli, A. et al. Thyroid cancer in HCV-related chronic hepatitis patients: a case-control study. Thyroid 17, 447–51 (2007).

Duberg, A. S. et al. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and other nonhepatic malignancies in Swedish patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 41, 652–9 (2005).

Giordano, T. P. et al. Risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and lymphoproliferative precursor diseases in US veterans with hepatitis C virus. JAMA. 297, 2010–7 (2007).

Fiorino, S. et al. Association between hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus infection and risk of pancreatic adenocarcinoma development: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pancreatology 13, 147–160 (2013).

Xing, S. et al. Chronic hepatitis virus infection increases the risk of pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 12, 575–583 (2013).

Zeng, H. M. & Chen, W. Q. Cancer Epidemiology and Control in China: State of the Art. Progress In Chemistry 25, 1415–1420 (2013).

Hermine, O. et al. Regression of splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes after treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 89–94 (2002).

Vallisa, D. et al. Role of antihepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment in HCV-related, low-grade, B-cell, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: A multicenter Italian experience. J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 468–473 (2005).

Gisbert, J. P., García-Buey, L., Pajares, J. M. & Moreno-Otero, R. Systematic review: regression of lymphoproliferative disorders after treatment for hepatitis C infection. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 21, 653–662 (2005).

De, R. V. et al. Premalignant and malignant lymphoproliferations in an HCV-infected type II mixed cryoglobulinemic patient are sequential phases of an antigendriven pathological process. Int. J. Cancer 87, 211–216 (2000).

Pileri, P. et al. Binding of hepatitis C virus to CD81. Science 282, 938–941 (1998).

Machida, K. et al. Hepatitis C virus induces a mutator phenotype: enhanced mutations of immunoglobulin and protooncogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 4262–4267 (2004).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Mr. Shanhong Wei and Wang Bing for assistance with data analysis. This study was supported by a project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD) and Innovative Team of Jiangsu Province - CXTDA2017023 [Li].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L., W.H.Z.: design, analysis of data, and the supervision of the study. B.L.,Y.X.Z.: acquisition and interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, B., Zhang, Y., Li, J. et al. Hepatitis C virus and risk of extrahepatic malignancies: a case-control study. Sci Rep 9, 19444 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-55249-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-55249-w

This article is cited by

-

Investigating the correlation between prominent viruses and hematological malignancies: a literature review

Medical Oncology (2024)

-

Impact of Interferon-Free Direct-Acting Antivirals on the Incidence of Extrahepatic Malignancies in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C

Digestive Diseases and Sciences (2023)

-

The association between hepatitis C virus infection and renal cell cancer, prostate cancer, and bladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.