Abstract

3-ketodihydrosphingosine reductase (KDSR) is the key enzyme in the de novo sphingolipid synthesis. We identified a novel missense kdsrI105R mutation in zebrafish that led to a loss of function, and resulted in progression of hepatomegaly to steatosis, then hepatic injury phenotype. Lipidomics analysis of the kdsrI105R mutant revealed compensatory activation of the sphingolipid salvage pathway, resulting in significant accumulation of sphingolipids including ceramides, sphingosine and sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P). Ultrastructural analysis revealed swollen mitochondria with cristae damage in the kdsrI105R mutant hepatocytes, which can be a cause of hepatic injury in the mutant. We found elevated sphingosine kinase 2 (sphk2) expression in the kdsrI105R mutant. Genetic interaction analysis with the kdsrI105R and the sphk2wc1 mutants showed that sphk2 depletion suppressed liver defects observed in the kdsrI105R mutant, suggesting that liver defects were mediated by S1P accumulation. Further, both oxidative stress and ER stress were completely suppressed by deletion of sphk2 in kdsrI105R mutants, linking these two processes mechanistically to hepatic injury in the kdsrI105R mutants. Importantly, we found that the heterozygous mutation in kdsr induced predisposed liver injury in adult zebrafish. These data point to kdsr as a novel genetic risk factor for hepatic injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sphingolipids are essential lipid components of eukaryotic cell membranes and play important roles in membrane trafficking, cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and cell migration1,2. Sphingolipids are synthesized via a de novo synthetic pathway as well as a salvage pathway. The de novo synthesis of sphingolipids begins with condensation of the palmitoyl-CoA and L-serine by serine palmitoyltransferase, to produce 3-ketodihydrosphingosine. 3-ketodihydrosphingosine is then reduced by KDSR to generate dihydrosphingosine, which can then be converted to various ceramides by five different ceramide synthases. The salvage pathway starts from degradation of sphingomyelin (SM) or glycosylated ceramides to ceramide, and degradation of ceramide to sphingosine (Sph), which is then secreted to the cytosol. Cytosolic Sph can be used to synthesize ceramide or S1P3,4,5. Among sphingolipids, S1P is well studied as it mediates diverse cellular processes, including cell growth, suppression of apoptosis, differentiation, angiogenesis and inflammation, and also serves in an autocrine and paracrine signaling via five different S1P receptors6,7,8. Additionally, S1P in the nucleus produced by sphingosine kinase 2 (sphk2) is known to control gene transcription9. S1P appears to play a role in the inflammation of typical steatohepatitis10,11, although the mechanism of its effects remain unknown.

KDSR is a key enzyme in the synthesis of sphingolipid. However, since KDSR was identified 20 years ago in yeast12, in vivo function of KDSR has been under-studied due to the lack of an animal model. We found progression of liver disease phenotype in the kdsr mutant zebrafish and we investigated the mechanism of disease pathogenesis in this paper. Given the well-conserved sphingolipid synthetic pathway in zebrafish and high protein homology with human KDSR, we expect that people who carry KDSR mutations may have liver disease. While recent human studies showed that mutations in KDSR are associated with keratinization disorder13,14, liver abnormalities in those patients have not been studied to date.

Zebrafish are a powerful model to study liver disease since their liver possess cells that are functionally analogous to those of mammals15 and have similar lipid metabolism to humans16. We previously discovered the novel zebrafish kdsrI105R mutant that encodes a missense mutation in 3-ketodihydro-sphingosine reductase (kdsr) from a forward genetic screening to identify mutants with post-developmental liver disease17. Here, we use the kdsrI105R mutant to explore its role in the pathogenesis of hepatic injury. We found that accumulation of ceramides, Sph, and S1P resulted from activation of the lysosomal sphingolipid salvage pathway in the kdsrI105R mutant. Additionally, we found that oxidative stress by elevation of mitochondrial β-oxidation and ER stress in the kdsrI105R mutant can mediate mitochondrial cristae and liver injury. Through genetic interaction of kdsr and sphk2 mutations, we also found that sphk2-mediated S1P accumulation is a key factor in both oxidative and ER stress in the kdsrI105R mutant.

Results

kdsr I105R mutant zebrafish developed progressive liver injury and hepatic injury during post-developmental stage

From the previous forward genetic screening to identify zebrafish mutants with post-developmental liver defects17, we identified a mutant showing progression of liver defects ranging from hepatomegaly at 6 days post fertilization (dpf) to steatosis at 7 dpf, and to a more advanced hepatic injury thereafter (Fig. 1A–C). We identified causative mutation by using whole genome sequencing of normal looking siblings and homozygous mutants (Supporting Fig. 1). The mutant carried a missense mutation in 3-ketodihydrosphingosine reductase (kdsr). The protein homology comparison with human KDSR showed that the zebrafish kdsr had high homology with human KDSR (81% identity and 93% positivity, Supporting Fig. 2). The secondary structure of human KDSR was previously reported18 and the missense mutation tyrosine to guanine (T to G) caused the isoleucine (I) to arginine (R) change at the 105 amino acid residue of kdsr (Fig. 1D). Hepatocyte ballooning occurred at 7 dpf and advanced hepatic injury was identified at 8 dpf (Fig. 1C). We also noticed that all homozygous mutant died between 8 to 10 dpf. The relative mRNA expression of genes associated with inflammation, including tumor necrosis factor alpha (tnfa) and interleukin 1 beta (il1b); and fibrosis, collagen type 1 alpha 1a (col1a1a) were significantly elevated in the kdsrI105R mutants compared to controls (Fig. 1E). Thus, the kdsr mutant recapitulated characteristics found in hepatic injury in humans.

Progression of liver injury in the KdsrI105R zebrafish mutant. Whole mount oil-red O (ORO) staining in wild type control sibling (A, left) and kdsr mutant (B, left) at 6 days post fertilization (dpf) and 7 dpf. ORO staining performed in transverse section of the liver (L, right panels of A and B). N = 10 per each. Lipid accumulation in the heart (h) and blood vessel (bv) are marked in images of panel B. H & E staining results in control at 7 dpf (left), mutant at 7 dpf (middle), and mutant at 8 dpf (right) (C, n = 6 per each). The magnified area depicts hepatocyte ballooning in mutants at 7 dpf. Images shown are representative of at least 10 other zebrafish or livers, respectively. Scale bars = 100 µm (whole mount ORO staining in A and B), 40 µm (ORO staining on the liver section in A and B), and 100 µm (H&E staining in C). The predicted protein structure of kdsr and the locus of the mutated amino acid is shown in (D). Relative mRNA expression of tnfa, il1b, and col1a1a in the wild type and mutant siblings is shown in (E). *P ≤ 0.05.

Inhibition of fatty acid synthase activity exacerbated steatosis phenotype rather than suppressing steatosis in the kdsr I105R mutant liver

To understand the mechanism of steatosis in the kdsrI105R mutant, we analyzed mRNA expression of proteins involved in lipid metabolism (Fig. 2A). We found significant increases of srebp1, which regulates genes essential for lipogenesis, and fasn, a gene regulated by srebp1 that plays a role in palmitate synthesis from acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA. We also found significant increases of srebp2, which is essential for cholesterol biogenesis and the regulation of lpl expression, which encodes lipoprotein lipase, a key enzyme in lipid uptake (Fig. 3A). The hyperlipidemic phenotype in the kdsrI105R mutant (Fig. 1B) may have activated the expression of srebp2 and lpl expression to reduce plasma lipid level in the plasma rather than to cause liver steatosis. Since an increase in fasn expression may induce lipid accumulation in the liver, we treated mutants with fasnall, an inhibitor of fasn to determine whether the steatosis resulted from increase of lipogenesis. Interestingly, we found that the fasnall treatment exacerbated the steatosis phenotype in the kdsrI105R mutant rather than suppressing lipid accumulation (Fig. 2B). This result suggests that fasn upregulation was required to facilitate mitochondrial β-oxidation, because palmitate is required for lipid transport to the mitochondria through cpt1, and one of the substrates of fasn, malonyl-CoA, is known to inhibit mitochondrial β-oxidation19. Elevation of cpt1 expression further supports the enhancement of mitochondrial β-oxidation in the kdsrI105R mutant (Fig. 2A), which is supported by the increase in oxygen consumption in the kdsrI105R mutants compared to control siblings at 7 dpf (Fig. 2C). Analysis of genes expressed in association with mitochondrial homeostasis revealed a significant increase in mfn1, important for mitochondrial fusion, opa1, which plays a role in mitochondrial fusion and cristae stability, pgc1a, a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis20, and nd1, a gene expressed in the mitochondria and encodes a subunit of NADH dehydrogenase, while expression of drp1, a gene required for mitochondrial fission was not changed (Fig. 2D).

Lipid metabolism- and mitochondrial homeostasis-associated gene expression, and oxygen consumption analysis in larvae. Relative mRNA expression of genes associated with lipid metabolism include sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (srebp1), fatty acid synthase (fasn), srebp2, lipoprotein lipase (lpl), and carnitine-palmitoyltransferase I (cpt1) (A). Oil red O staining in control, kdsrI105R mutant, and kdsrI105R mutant siblings after fasnall treatment at 7 dpf; 1 µM fasnall treatment was performed from 4 dpf to 7 dpf (B). Images shown are representative of at least 10 in total. Scale bar in B = 100um. Average oxygen consumption rate was measured from 7 groups (3 larvae per group) of control and mutant siblings for 30 minutes (C). Relative mRNA expression of genes associated with mitochondrial homeostasis include dynamin related protein 1 (drp1), mitofusin 1 (mfn1), optic atrophy type 1 (opa1), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (pgc1a), and NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain1 (nd1) (D). Error bars indicate standard deviation of the mean. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.005.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging of hepatocytes. 8,000x magnification in wild type at 7 dpf (left), kdsrI105R mutant at 7 dpf with mild phenotype (middle), and kdsrI105R mutant at 7.5 dpf with severe defect (right) (A). One of representative mitochondria is outlined with white color. N, nucleus. Normal looking mitochondria and abnormal mitochondria were marked with white and black asterisks, respectively. 20,000x magnification images are shown in (B). Images shown are representative of 2 other animals. Scale bars = 2 µm (panel A), 0.8 µm (panel B). Lip, lipid drops.

Ultrastructural analysis of mitochondrial cristae in the kdsr I105R mutant

Elevation of mitochondrial β-oxidation and oxygen consumption suggested that there may be accumulation of oxidative stress molecules in the mitochondria, which can induce mitochondrial injury. To test this possibility, we performed ultrastructural analysis wild-type control at 7 dpf and kdsrI105R mutant livers at 7 dpf and 7.5 dpf. We found that there was accumulation of mitochondria with less dense cristae structures in hepatocytes of mutant at 7 dpf (Fig. 3A middle panel). There was also a more severely damaged and swollen mitochondrial phenotype in the kdsrI105R mutant at 7.5 dpf (Fig. 3A right panel), suggesting progression of mitochondrial injury from less dense cristae damage to swollen and disrupted cristae phenotype. This could be a key factor for progression of liver phenotype from steatosis to hepatic injury phenotype in the kdsrI105R mutant. Higher magnification of mitochondria (Fig. 3B), clearly showed cristae defects in the mutants. Activation of opa1 (Fig. 2D) further supported damage of the cristae, because opa1 plays a role in stabilizing injured mitochondrial cristae21.

Kdsr I105R mutants accumulated sphingolipids through activation of the sphingolipid salvage pathway

Because kdsr is a key enzyme for the de novo synthesis of sphingolipids, we expected the missense mutation of kdsr to affect sphingolipid synthesis. Sphingolipidomics analysis data indicated accumulation of downstream components of sphingolipids, suggesting that the missense mutation might cause gain of kdsr function (Fig. 4A). To test our hypothesis, we generated a kdsr null mutant by CRISPR/Cas9 gene targeting in zebrafish, carrying premature stop codon by deletion/insertion in target region at exon 3 (Supporting Fig. 3). The kdsrcri null mutant showed the same phenotype as the kdsrI105R mutant (Supporting Fig. 3A) and histological analysis of the kdsrcri mutant showed that similar liver abnormality and steatosis observed in the kdsrI105R mutant (Supporting Fig. 3B). Additionally, the sphingolipid profile mirrored that of the kdsrI105R mutant (Supporting Fig. 3C,D). Complementation test was performed by crossing the heterozygous kdsrI105R mutant and the kdsrcri null mutant. We confirmed that the biallelic mutant (kdsrI105R/cri) also developed the same phenotype as the kdsrI105R mutant (Supporting Fig. 4). We concluded that the missense mutation definitely induced loss of kdsr function. To understand how loss of kdsr function led to accumulation of downstream sphingolipids, we investigated the sphingolipid salvage pathway, which involves the degradation of SM and hexosyl- ceramides. SM species analysis showed significant decrease in the concentration of long chain SM species in the kdsrI105R mutant, including C16-SM, the most abundant SM (>4000 pmole per sample), C14-SM, C18-SM and C20:1-SM in the kdsrI105R mutant, while there were statistically significant increase of very long chain SM species such as C22-SM, C24:1-SM and C26:1-SM (Fig. 4B). We also found significant decrease of hexosyl-ceramides (glucosyl- or galactosyl-ceramides), including C16-, C18:1-, C18-, C20-, C26-Hexosyl-ceramides (Fig. 4C). This result suggests that C16-SM and hexosyl-ceramides were mainly used for the sphingolipid salvage pathway in the kdsr mutant zebrafish to compensate loss of sphingolipid de novo synthetic pathway. mRNA expression analysis showed a significant increase gba, which degrades glucosyl-ceramide into ceramides, asah1b, which is associated with lysosomal degradation of ceramides, and a decrease of asah2, a key enzyme in the plasma membrane, and acer2, which is found in the Golgi (Fig. 4D). Because SM is initially converted to ceramide by lysosomal acid sphingomyelinase encoded by smpd1, we also examined smpd1 expression and found no significant change in the kdsrI105R mutant (Fig. 4D). This result suggests that the lysosomal sphingolipid salvage pathway caused SM and hexosyl-ceramides degradation by transcriptional activation of gba and asah1b in the kdsrI105R mutant, and resulted in the accumulation of ceramides, Sph and S1P in the mutant. We also found transcriptional activation of sphk2 in the kdsrI105R mutant, while no change was detected in sphk1 expression (Fig. 4D). This result suggests that sphk2 is the major kinase involved in S1P accumulation in the mutant. In addition, mRNA expression of spl, the enzyme that mediates the degradation of S1P increased and possibly was induced to reduce accumulated of S1P in the kdsrI105R mutant (Fig. 4A). Further, we analyzed gene expression of salvage pathway related in the kdsrcri mutant to determine whether activation of sphingolipid salvage pathway is conserved in the kdsr null mutant (Supporting Fig. 3E). We found significant increases of asah1b and spl in the kdsrcri mutant, which is same as in the kdsrI105R mutant. Importantly, we found activation of smpd1, gba, ash1a and acer2 in the kdsrcri mutant, which suggesting kdsrcri mutant may have higher activity in salvage pathway compared to kdsrI105R mutant. Although both mutants have similar pathological defects, kdsrI105R mutant may have minimal activity of kdsr function.

Activation of the sphingolipid salvage pathway in the kdsrI105R mutant zebrafish. Accumulation of ceramides (cers), sphingosine (Sph) and sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) (A), decrease of SM (B) and hexosyl-ceramides (C) in the kdsr mutant larvae at 7 dpf. Thirty larvae were used per each assay and assays were performed in triplicate. Relative mRNA expression in sphingolipid salvage pathway components; acid sphingomyelinase/sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase 1 (smpd1), β-glucocerebrosidase (gba), acid ceramidase 1b (asah1b), neutral ceramidase 2 (asah2), alkaline ceramidase 2 (acer2), and sphingosine 1-phosphate lyase (spl) (D, left). sphingosine kinase expression in the kdsrI105R mutant; sphingosine kinase 1 (sphk1), sphingosine kinase 2 (sphk2) (D, right). Error bars indicate standard deviation of the mean. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.005.

Depletion of Sphk2 suppressed liver injury in the kdsr I105R mutant

A previous report showed that sphk2 is the main sphingosine kinase in zebrafish embryo22. Because of transcriptional up-regulation of sphk2 in kdsrI105R mutant, and since accumulation of S1P has been reported to be involved in inflammation and steatohepatitis10, we tested whether the loss of sphk2 in the kdsrI105R mutant can suppress liver defects. We used an sphk2wc1 mutant, a null mutant23. By crossing chimeric heterozygous (kdsrI105R/+; sphk2wc1/+) mutants, we were able to obtain double homozygous mutants, which exhibited complete suppression of liver defects seen in the kdsrI105R mutant (Fig. 5A). Heterozygous kdsrI105R/+, sphk2wc1/+ mutants or homozygous sphk2wc1 mutant had normal livers (data not shown). The qPCR analysis demonstrated that genes associated with inflammation (tnfa, il1b), tissue injury (a1at) and fibrosis (col1a1a) were all significantly reduced in the double mutant (Fig. 5B). We also investigated effects of sphk2 mutation on the sphingolipid salvage pathway. Significant suppression of mRNAs of spl and spp1, which functions to convert S1P to Sph, and asah1b was detected in kdsrI105R; sphk2wc1 double mutant, whereas no significant change was detected in asah2 levels. The sphk2wc1 mutant showed significant decrease of asah2 expression. However, asah1a gene expression was elevated in both sphk2 mutant and kdsrI105R; sphk2wc1 double mutant (Fig. 5C). The qPCR results suggested that the salvage pathway is still activated in the kdsrI105R; sphk2wc1 mutant by elevating asah1a expression, a homolog of asah1b in zebrafish to maintain essential sphingolipids homeostasis for survival as additional compensatory mechanism. In addition, sphk2 depletion attenuated expression of genes (spl, spp1) involved in regulation of S1P levels. Thus, our results suggest that sphk2-mediated S1P accumulation might have a key role in the development of liver defects in the kdsrI105R mutant. Histological analysis of wt, kdsrI105R mutant and kdsr; sphk2 double homozygous mutant showed that suppression of liver defects by sphk2 depletion in the kdsrI105R mutant (Fig. 5D).

Sphk2 deletion suppresses liver defects in the kdsrI105R mutant. Images of live wild type (wt), kdsrI105R, and kdsrI105R; sphk2wc1 double mutant at 7 dpf (A). Scale bar = 0.25 mm. Relative mRNA expression of sphk2 and other genes associated with inflammation (tnfa, il1b), tissue injury (alpha1-anti-trypsin (a1at)) and fibrosis (col1a1a) (B), sphingolipid salvage pathway related genes (C) in wt, kdsrI105R, sphk2wc1, and kdsrI105R; sphk2wc1 mutant siblings. spp1, (S1P-phosphohydrolase 1). Images of H&E and ORO staining in livers of wt, kdsrI105R and kdsrI105R; sphk2wc1 double mutants (D, n = 6). Error bars indicate standard deviation of the mean. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.005. Scale bare in D = 100 µm.

Sphk2 played a key role in oxidative stress and ER stress in the kdsr I105R mutant

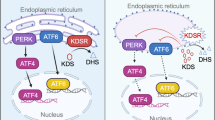

Both oxidative stress and ER stress are major contributors to mitochondrial injury and liver disease24,25. We first analyzed the expression of genes activated by oxidative stress. We found significant elevation of oxidative stress-related genes in the kdsrI105R mutants compared to controls, suggesting that liver injury may be related to increased oxidative stress (Fig. 6A). Importantly, significant elevation of oxidative stress-related genes in the kdsrI105R mutant were suppressed by introducing the sphk2 null mutation into the kdsrI105R mutant (Fig. 6A). To investigate whether ER stress also contributed to liver defects in the kdsrI105R mutant, we analyzed the expression of genes associated with ER stress response in each control and mutant sibling, including atf4, and its target gene gadd45a. The Ire1, one of upstream component of nfkb transcription that functions as endonuclease to process xbp1, resulting in increased spliced form of xbp1 (xbp1-s) under ER stress condition. The atf6, and targets including xbp1, ddit3, edem1, bip, dnajc3, and grp94 were also analyzed. Additionally, bim, bida, and baxb were analyzed, which were known to be associated with ER stress-induced apoptosis through mitochondrial injury. Especially, bip, dnajc3, and grp94, molecular chaperons activated by unfolded protein folding response, are a main cause of ER stress. All of the tested genes in the ER stress pathway were all elevated in the kdsrI105R mutant (Fig. 6B). Although transcriptional activation of ire1 in the kdsrI105R mutant was not suppressed by sphk2 mutation, significant decrease of xbp1-s was found in both the sphk2wc1 mutant and kdsrI105R; sphk2wc1 double mutant. This result suggests that sphk2 expression was required for endonuclease activity of Ire1. Transcriptional activation of atf6 was found in the sphk2wc1 mutant; however, sphk2 depletion limited the activation of atf6 in the kdsrI105R mutant. Our result showed that even partial suppression of atf6 by sphk2 knockout was sufficient to suppress downstream target gene transcriptions including ddit3, edem1, bip, dnajc3, and grp94. These data suggest that sphk2 is a key mediator in the elevation of oxidative stress and ER stress in the kdsrI105R mutant.

mRNA expression of genes associated with oxidative stress and ER stress. Relative mRNA expression of oxidative stress-related genes; nuclear factor erythroid 2 - related factor 2 (nrf2), superoxide dismutase 2 (sod2), glutathione S transferase pi 1 and 2 (gstp1/2), glutathione peroxidase 1a/4a (gpx1a, gpx4a), peroxiredoxin 4 (prdx4), and thioredoxin-like 1/4 (txnl1, txnl4) (A) and ER stress/UPR response related genes; activating transcription factor 4 (atf4), growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible 45 alpha (gadd45a), inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (ire1), nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (nfkb), X-box binding protein 1 (xbp1), spliced form of xbp1 (xbp1-s), activating transcription factor 6 (atf6), DNA damage-inducible transcript 3 (ddit3), ER degradation-enhancing alpha-mannosidase-like 1 (edem1), binding immunoglobulin protein (bip), DnaJ homolog subfamily C member 3 (dnajc3), glucose-regulated protein 94 (grp94), Bcl2 interacting mediator of cell death (bim), BH3-interacting domain death agonist a (bida), and Bcl2 associated x b (baxb) (B). Error bars indicate standard deviation of the mean. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.005.

Depletion of glutathione in the kdsr I105R mutant

Glutathione (GSH) is a key antioxidant that protects cellular components from oxidative stress and injury. A reduction in the ratio of GSH to GSSG indicates that cells have increased susceptibility to oxidative stress26,27. The increase in mRNA expression of components of the redox pathway (Fig. 6A) in the kdsrI105R mutant raised the possibility of severe oxidative stress. Therefore, we measured GSH, GSSG, and protein-thiol levels in the kdsrI105R mutant. We found a significant reduction in both GSH and GSSG levels (Fig. 7A,B). Although the GSH/GSSG ratio was not significantly decreased, the decrease in total GSH levels suggests that the kdsrI105R mutant might have limited capacity to protect proteins from ROS induced damage (Fig. 7C). Further, a significant decrease in the protein-thiol levels suggested accumulation of oxidized proteins in the kdsrI105R mutant (Fig. 7D). In aggregate, these data suggest that GSH depletion/oxidative stress may play critical role in hepatocellular injury found in the kdsrI105R mutant.

GSH, GSSG, and protein-thiol levels in control and kdsrI105R mutant. Quantification of GSH (A), GSSG (B), GSH to GSSG ratio (C), and protein-thiol (D) in control and kdsrI105R mutant. Three groups of control and mutant were used for analysis and each group contains 5 larvae. Relative mRNA expression of glutathione reductase (gsr) and glutathione synthetase (gss) in control and mutant (E). The working model illustrating that deleterious mutations in kdsrI105R induced transcriptional upregulation of sphk2, resulted in S1P accumulation. S1P accumulation elevated oxidative stress and ER stress mediated mitochondrial injury, hepatic injury and then steatohepatitis. GSH depletion might sensitize kdsrI105R mutant to oxidative stress (F). Error bars indicate standard deviation of the mean. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.005.

To understand the mechanism of GSH depletion, we examined mRNA expression of gsr, an enzyme that converts GSSG to reduced GSH. We also examined genes associated with GSH synthesis including gss, which synthesizes GSH from r-glutamylcysteine and glycine; and gclc, which synthesizes r-glutamylcystein (Fig. 7E). Collectively, the genes involved in GSH synthesis were elevated in the kdsrI105R mutant, suggesting that GSH depletion was not a result of downregulation of those enzymes, and might be caused by limitation of substrate such as cysteine. Further, we treated control and mutant larvae with n-acetyl cysteine (NAC) to address whether NAC treatment can induce GSH synthesis and reduce ROS in kdsr mutants. The result showed that NAC treatment did not increased GSH level in both control and mutant larvae, which suggests that NAC treatment might not be effective in elevating GSH levels in vivo in zebrafish. However, we found a significant decrease of the oxidized form of GSH (GSSG) in control siblings compared to mutants. As a result, NAC treatment elevated GSH/GSSG ratio in the control larvae, which led to ROS a decrease in ROS. However, NAC treatment was not effective in elevating GSH/GSSG ratio and suppressed ROS levels in the kdsr mutants (Supporting Fig. 5).

Hepatocellular injury in heterozygous kdsr I105R/+ mutant adults

To investigate whether the heterozygous kdsr mutation alone leads to hepatocellular injury in adult zebrafish, we also analyzed livers of wild type and kdsrI105R/+ heterozygous mutant siblings. Ballooning of hepatocyte phenotype (Fig. 8A,B) and an increase of serum alanine-aminotransferase (ALT) levels (Fig. 8C) were identified in adults. Additionally, mRNA levels of tnfa, il1b and col1a1a expression were increased in the livers of kdsrI105R heterozygous mutants (Fig. 8D), similar to homozygous mutant larvae (Fig. 1E). To determine whether the heterozygous mutation also can enhance the sphinggolipid salvage pathway similar to homozygous mutant larvae, we analyzed genes involved in the sphingolipid salvage pathway. qPCR analysis revealed significant elevation of sphk2 and asah1a mRNAs in the liver (Fig. 8E). These data suggest that the liver injury phenotype of the kdsrI105R/+ adult may also result from S1P accumulation in a fashion similar to that of the kdsrI105R homozygous mutant.

Predisposed liver injury in the kdsrI105R/+ adult zebrafish. H & E staining of wild type liver (A) and heterozygous kdsr mutant liver (B). The inset depicts high resolution of the identified areas. Images shown are representative of at least 10 in total. Scale bar for A and B is 100 µm. Serum ALT test (C) in wild type and heterozygous kdsr mutant (n = 3). Relative mRNA expression of tnfa, il1b, and col1a1a (D) and sphk2, asah1a, asah1b, and asah2 (E) in wild type and kdsrI105R/+ mutants (n = 3). Error bars indicate standard deviation of the mean. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.005. ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

Discussion

In this study, we have found that a novel kdsrI105R mutant had progression of liver disease from hepatomegaly to hepatic injury. Since KDSR deficiency was discovered about one year ago, liver abnormalities have not been addressed in KDSR human patients. It is possible that mutations in patients were hypomorphic, and biallelic mutations might not be enough to activate the sphingolipid salvage pathway. Our working model (Fig. 7F) showed that suppression of kdsr function by either homozygous or heterozygous mutations can enhance the sphingolipid salvage pathway, and that excess Sph is mainly phosphorylated by sphk2. Increase of S1P levels in turn might trigger oxidative stress via elevation of mitochondrial β-oxidation. Additional ER stress could be attributed to mitochondrial damage. Both stresses associated with liver disease were suppressed by loss of sphk2 function. Significant decrease of GSH in the kdsr mutant might sensitize kdsr mutant larvae against to oxidative stress. Mitochondrial injury could be upstream event preceding hepatic injury in the homozygous kdsrI105R mutant larvae and heterozygous kdsrI105R/+ mutant adults. Thus, we found how kdsr dysfunction can induce hepatic injury phenotype in both homozygous kdsr mutant larvae and heterozygous kdsr mutant adult fish. Our results suggest that genetic variant causing decrease of kdsr activity could be an underlying risk factor for development of liver disease and people who carry deleterious mutations in adult might be highly susceptible to liver disease such as steatohepatitis or advanced liver disease such as fibrosis or hepatocellular carcinoma.

The progressive liver injury phenotype identified here was associated with progression of mitochondrial injury phenotype from less dense cristae structure to swollen mitochondria. The progressive liver defect was similar to the defect observed in the electron transfer flavoprotein alpha (etfa) mutant, a zebrafish model of multiple acyl-coA dehydrogenase deficiency28, suggesting that mitochondrial defects could be key factor in liver phenotype in the kdsrI105R mutant.

The homoeostasis of cellular sphingolipids are tightly controlled by both a de novo synthesis (initiated from palmitoyl-CoA and serine to produce ceramides) as well as a salvage catabolic pathway (initiated from complex sphingolipids such as glycosylated ceramides or sphingomyelins to produce ceramides) through the regulation of the intra-cellular levels of ceramide. Ceramide is the central molecule in the sphingolipid metabolic pathway that can be converted to various sphingolipid species29. Diet-induced alterations in ceramide via both de novo and salvage sphingolipid synthesis demonstrate that nutrition has the ability to alter sphingolipid metabolism and in turn downstream signaling pathways30. Enzymes of the salvage pathway have been implicated in dietary manipulations of ceramide levels. Ceramide acts as the central molecule in the sphingolipid metabolic pathway. A previous study showed that radio-labeled palmitate was found in the dihydrosphingosine, and then in the ceramides via de novo synthesis. However, they also found ceramides produced via salvage pathway at the same time. Thus, palmitic acid treatment can enhance ceramide formation through the both de novo and salvage pathway31. Furthermore, administration of high fat diet enhanced mRNA expression and activity of acid sphingomyelinase and neutral sphingomyelinase in rat liver32 and mouse adipose tissue33. Pharmacological inhibition of acid sphingomyelinase inhibited ceramide induction by high fat diet in plasma and adipose tissue in mice34. However, compared to studies examining de novo sphingolipid synthesis, regulation of the salvage pathway has not been well-studied. Future experimentation that include modeling of sphingolipid metabolism can help understand the role the salvage pathway in mammals. To determine impact of external feeding in sphingolipid salvage pathway in zebrafish after consumed own egg yolk, we performed a diet experiment in control and kdsr mutant siblings at 7dpf. We found egg yolk feeding induced significant increase of gene expression involved in salvage pathway in both control and mutants (Supporting Fig. 6). Additionally, this result suggested that activation of salvage pathway in the kdsr mutant was not induced by starvation.

Loss of kdsr function should in theory inhibit de novo synthesis of sphingolipids and deplete downstream sphingolipids. Due to the current lack of LC-MS methods to quantify the substrate of kdsr, 3-keto-dhSph, it is expected that significant amount of 3-keto-dhSph would be accumulated in the mutant. As 3-keto-dhSph and Sph are isomers, the kdsr mutant may instead produce 3-keto-dihydroceramide, which may have inhibitory effect on dihydroceramide desaturase, the enzyme that generates ceramide from dihydroceramide. This hypothesis may explain how endogenous dhSph and dihydroceramide, possibly transported from egg yolk accumulated in the kdsr mutant (Supporting Fig. 7). As 3-keto-sphingolipids have not been sufficiently studied, there is unfortunately no quantification methods available yet. Further, future studies on sphingolipids with the 3-keto moiety will be necessary to answer this question. In this study, we found that inhibition of the kdsr function activated the sphingolipid salvage pathway possibly to compensate for the inhibition of the de novo synthesis pathway. As a result, Sph, S1P and ceramides may have accumulated in the kdsrI105R mutant. Because the larvae could have used the egg yolk as nutrient by 6 dpf, probably there was no external source of sphingolipids without feeding the larvae, thus the salvage pathway would be the only way to produce downstream sphingolipid species. Previous studies have shown that accumulation of ceramides may induce steatohepatitis in35,36,37,38. However, our genetic study of the interaction of sphk2 and kdsr mutation suggested that S1P is likely the cause of the observed liver phenotype (Fig. 5).

Sphk1 was found to be necessary for S1P-mediated steatohepatitis in a high fat diet-induced liver disease in mice; however, the role of SphK2 was not investigated10. Notably, our findings raised the possibility that sphk2 is the major sphingosine kinase involved in steatohepatitis (Fig. 5B) and this finding is consistent with a previous report that showed sphk2 functions as the main sphingosine kinase for S1P production in zebrafish22. Importantly, a significant increase of SPHK2 expression was found in both steatosis and steatohepatitis cases of multiple patients39. Thus, an important finding from the current study is that sphk2 may play a key role in the development of hepatic injury associated with kdsr mutation and then steatohepatitis. The effect of high fat diet in the kdsrI105R mutant remains to be determined.

Cellular GSH maintains the oxidation status of thiols in critical proteins and defends cells against to reactive oxygen species by its reducing capacity40. GSH depletion might reduce the buffering capacity of GSH against oxidative stress, which plays a key role in the aging process and the pathogenesis of many diseases41,42. Based on mRNA expression analysis, enzymes responsible for GSH synthesis and reduction are highly upregulated in the kdsr mutant, although total GSH level is significantly lower than control siblings (Fig. 7). This result suggests that GSH depletion may occur by depletion of a substrate(s) for GSH synthesis. Further investigation will be necessary to address the mechanism of GSH depletion. We propose that cysteine depletion might affect GSH levels in the kdsr mutant, since cysteine is tightly regulated in the liver for both GSH synthesis and protein synthesis43. We tested whether NAC treatment can elevate GSH synthesis, but NAC treatment did not elevate GSH in both control and kdsr mutants (Supporting Fig. 5). A previous study showed that NAC concentrations would have to exceed 1 mM, which is therapeutically unattainable in vivo to achieve maximum rates of GSH synthesis44. The NAC treatment might not be enough to elevate GSH synthesis in zebrafish same as in human. In this paper, we were not able to make a conclusion whether cysteine depletion is the main cause of GSH depletion, because sub-lethal dose of the NAC treatment did not elevate GSH levels in vivo. Further investigation will be necessary to determine the mechanism of GSH depletion in the kdsr mutant in the future.

Collectively, our findings indicate that kdsr deletion leads to compensatory activation of the sphingolipid salvage pathway and S1P accumulation, which can result in increased mitochondrial activity, oxidative stress, and ER stress and subsequent hepatocellular injury. The data point to the possibility that kdsr could be a novel genetic risk factor for steatosis and liver injury.

Methods

Animals

All methods of this article were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations of the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and Medical University of South Carolina’s Division of laboratory animal resources (DLAR). All experiments on zebrafish were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Medical University of South Carolina (IACUC protocol #3364).

The zebrafish strain used in this study was AB/TU. Adults were maintained at 28.5 °C and fed twice a day with brine shrimp and Tetramin flake (Tetra US, Blacksburg, VA). Embryos were obtained from natural mating and raised at 28.5 °C in egg water (0.3 mg of sea salt/L). KdsrI105R and sphk2wc123 lines were outcrossed with wild type AB/TU at least five times to reduce additional background mutations and maintenance. The kdsrI105R mutant were genotyped using 5′-GTGGTTCTTTGCATTTCTGTTGATGT-3′ and 5′-ATGGCGAAAGGATTTTATGAATTGTTAAACATAC-3′, 30 cycles of PCR with 56 °C annealing temperature and then digested with Hpy188I (R0617, NEB, inc.) for 1 hr. sphk2wc1 was genotyped as described in the previous paper23. A kdsr null mutant was generated by CRISPR/Cas9 gene targeting in the laboratory. The guide RNA for kdsr was designed to target exon 3 of kdsr (5′-GGTTCAGGCTAAGAAAGAAGTGG-3′); T7-gRNA-kdsr nucleotides (5′-GAAATTAATACGACT CACTATAGGTTCAGGCTAAGAAAGAAGGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGCAAGTTAAAAT) were used as template for gRNA synthesis. 50 to 100 pmole of guide RNA and 100 pmole of Cas9 RNA were co-injected at 1 cell-stage eggs. Injected embryos were raised and outcrossed with wild type to produce progeny. Each of the progenies was genotyped using 5′-GGTGTTACACAATTTGAAAACCATTTACC ACTG-3′ and 5′- TCCTTTGTTAAAGACATACATACT TGCTTATC-3′ primers, and deletions were confirmed by sequencing. Identified founder fish was used to generate stable lines. Siblings were used as controls.

Whole genome sequencing

Genomic DNA from 10 normal siblings and 10 homozygous mutants were used as template DNAs for whole genome sequencing. The MUSC Sequencing Core performed sequencing of samples using an Illumina HiSeq2500 Platform with 150 bp paired-end reads, resulting in approximately 10 fold genomic coverage. The sequencing results were uploaded to the SNPtrack Mapping server (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/ snptrack/), and mapped mutations re-confirmed by sequencing and genotyping of individual mutants. The sequencing results were submitted to NCBI Short Read Archive (SRA) database under the BioSample accessions SAMN10247386 and SAMN10247387.

Oil Red O (ORO) Staining

For whole mount staining at the larval stage, we used the method previously described28. Briefly, larvae were fixed in 4% PFA overnight. The same numbers of control and mutant larvae (5 to 10 larvae each) were processed together in the same tube. After staining, larvae were briefly rinsed in PBS-Tween and fixed in 4% PFA for 10 minutes. Larvae were mounted in glycerol prior to imaging. For ORO staining on transversely sectioned larvae, frozen sections with 10 µm thickness were dried at room temperature for 5 minutes. 150 µl of working ORO solution was added to slides and stained for 30 seconds. They were then washed with distilled water and mounted using 75% glycerol.

H&E staining

Embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde from overnight to two days at 4 °C. Fixed embryos were embedded in 1.2% agarose/5% sucrose, and saturated in 30% sucrose at 4 °C for 1 to 2 days. Blocks were frozen using liquid nitrogen. 10 µm sections were collected on microscope slides using a Leica cryostat. For adult liver histology, truncated bodies were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde from overnight to two days at 4 °C and processed for embedding in paraffin. Paraffin sections were used for H&E staining, which was conducted in the Histo-Core lab at Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). Images were taken with AxioCam ICC3 attached to Zeiss Axio-Imager M2.

Blood preparation and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) measurements

Zebrafish blood was obtained by minimally invasive blood collection method using a heparinized needle. The site for blood collection is along the body axis and posterior to the anus in the region of the dorsal aorta. Blood was collected from adult zebrafish, 20 hours after feeding and diluted 1:10 in PBS. The average volume of blood collected from a three-individual fish (average body weight = 0.6 g) was 25 µL. Plasma was separated by centrifugation for 15 minutes at 2,000 × g using a refrigerated centrifuge. 10 µl of plasma were transferred to 96-well plate and ALT was measured using a microplate-based ALT activity assay kit (Pointe Scientific, Cat. A7526).

Oxygen consumption assay of zebrafish larvae

Larval average oxygen consumption rate was determined using a sensor-dish reader (SDR) system (Loligo Systems, Viborg, DEN). Recordings were made once every 5 minutes for 1 hour using PreSens-SDR_v38 software (Loligo Systems, Viborg, DEN). Each well of 24-well optical fluorescence glass sensor microplate was filled with 125 µl of egg water and pre-ran for 20 minutes at 24 °C room. Three larvae were placed into wells of a 24-well plate, and then the plate was immediately sealed using parafilm and a silicone gel pad cover. Using PreSens–SDR_v38 software, dissolved oxygen amount was measured every 3 minutes for 30 minutes. Average oxygen consumption rate (nmol/L/min/fish) was calculated from change in O2 concentration over time. Data presented are from 7 measurements made with 3 larvae of each control and mutant siblings.

Lipid analysis

Three sets of 7 day-old control siblings (n = 30) and mutant siblings (n = 30) were anesthetized and collected in 15 ml tube and kept in −80 °C before submission to LC/MS/MS analysis at the MUSC Lipidomics core facility as previously described45,46.

Immunofluorescence Staining

To avoid variation of staining intensity, 3 of each control and mutant larvae were always processed together on the same glass slide. Slides were concurrently processed in Sequenza™ Slide Rack (Tedpella, Cat. 36105). Frozen sections were rehydrated in 1x PBS for 10 min at room temperature and blocked in 5% sheep serum in PBS for 2 hours. Sections were incubated with primary antibody to sod2 (Genetex, Cat. GTX124438, dilution 1:300) overnight at 4 °C, rinsed for 30 minutes (10 min × 3 times) with 1x PBS and then incubated for 2 hours with Alexa Fluor conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Sections were then washed with 1X PBS for 30 minutes and mounted in Vectashield with DAPI (Vector laboratories). Images were acquired using Zeiss Axiovert 200 M microscope with Zeiss AxioCam MRm and Hamamathu digital camera. Digital images were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS5 and Adobe illustrator CS5. All images received only minor modifications with control and mutant sections always processed in parallel.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Zebrafish were immersed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, overnight. Briefly, ultra-thin sections (70 nm) were positioned on copper grids, and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate for 10 minutes each. The sections were viewed on JEOL 1010 electron microscope at 80 kv in various magnifications. The images were captured with a Hamamatsu camera. Whole processes were performed in the Electron Microscopy core facility at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

Oligo-dT primed complementary DNA were prepared from total RNA isolated with Trizol® Reagent (Invitrogen, Cat. 15596-026) using superscript III First-Strand kit (Invitrogen, Cat.18080-051). Real-Time qPCR was performed with Bio-rad, CFX96 Real-time system with 1 cycle of 98 °C for 30 seconds, 45 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds, and 60 °C for 30 seconds using 50 ng cDNA, 4 pmoles of each gene-specific primers per 20ul reaction (Supporting Table 1), and SsoAdvanced™ Universal SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-rad, Cat. 172–5274). We used qPCR primers that were either used in previous studies in zebrafish47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54 or designed and tested in our lab (Supporting Table 1). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gapdh) was used as reference, and relative quantification was calculated using double delta Ct method. The qPCR was run in at least triplicate for each gene. Total RNA were isolated from 20 control siblings and 20 kdsrI105R homozygous mutant larvae. For multiple comparisons between wild type, kdsrI105R, sphk2wc1, and kdsrI105R; sphk2wc1 double homozygous mutants, kdsrI105R; sphk2wc1 double heterozygous mutants were crossed and siblings were anesthetized in 0.016% ethyl 3-aminobenzoate methanesulfonate salt (MS-222, Sigma-aldrich, E10521) with Ringer’s solution. Tips of tails were dissected for genotyping and bodies were kept in −80 °C. After genotyping of sibling larvae at 7 dpf, 5 of each wild type, single and double mutants were collected and total RNA were extracted for cDNA synthesis.

Measurement of intracellular reduced thiol levels

Triplicated groups of control and mutant larvae, each contained 5 larvae at 7 dpf stage were lysed in 75 ul of ice-cold lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, plus a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche/Sigma)]. 2ul of each lysate were immediately subjected to the reduced thiol measurement by using thiol fluorescent probe IV (Millipore) as previously described55. Fluorescent intensities were detected at 400Ex/465Em by Microplate Reader. The thiol fluorescent probe IV with lysis buffer was used as a negative control.

Measurement of GSH and GSSG levels

Quantitative determinations of GSH and GSSG levels were performed using the enzymatic-recycling method56. Triplicated group of each control mutant larvae were subjected to lysis. Each group contains 5 larvae at 7 dpf. Protein in the extracts from 5 larvae was precipitated by sulfosalicylic acid and the supernatant was then divided into two. For reduced GSH, the supernatant was incubated with the thiol fluorescent probe IV, and fluorescent intensities were measured at 400Ex/465Em. For total GSH (GSH + GSSG), the supernatant was neutralized by triethanolamine and incubated with the reduction system (containing NADPH and glutathione reductase) at 37 °C for 20 min. GSSG was calculated based on the results from reduced GSH and total GSH; the ratio of \(GSH/GSSG=\frac{[GSH]}{([TOTAL\,GSH]-[GSH])\,/\,2}\).

Statistical tests

All evaluations were performed with MS Excel software. The Student t-test was used to test significant differences between groups. For sphingolipid analysis, groups of siblings (30 per each group) were used for lipid extraction. For the qPCR studies, groups of siblings (minimum 10 per each group) were used to generate cDNAs, and three sets of qPCR were analyzed per each target gene. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Data Availability

The datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary information files).

Change history

15 July 2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

References

Hannun, Y. A., Luberto, C. & Argraves, K. M. Enzymes of sphingolipid metabolism: from modular to integrative signaling. Biochemistry 40, 4893–4903 (2001).

Simons, K. & Ikonen, E. Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature 387, 569–572, https://doi.org/10.1038/42408 (1997).

Don, A. S., Lim, X. Y. & Couttas, T. A. Re-configuration of sphingolipid metabolism by oncogenic transformation. Biomolecules 4, 315–353, https://doi.org/10.3390/biom4010315 (2014).

Merrill, A. H. Jr. Sphingolipid and glycosphingolipid metabolic pathways in the era of sphingolipidomics. Chem Rev 111, 6387–6422, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr2002917 (2011).

Kitatani, K., Idkowiak-Baldys, J. & Hannun, Y. A. The sphingolipid salvage pathway in ceramide metabolism and signaling. Cell Signal 20, 1010–1018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.12.006 (2008).

Strub, G. M., Maceyka, M., Hait, N. C., Milstien, S. & Spiegel, S. Extracellular and intracellular actions of sphingosine-1-phosphate. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 688, 141–155 (2010).

Maceyka, M., Harikumar, K. B., Milstien, S. & Spiegel, S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling and its role in disease. Trends in cell biology 22, 50–60, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2011.09.003 (2012).

Hait, N. C., Oskeritzian, C. A., Paugh, S. W., Milstien, S. & Spiegel, S. Sphingosine kinases, sphingosine 1-phosphate, apoptosis and diseases. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1758, 2016–2026, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.08.007 (2006).

Hait, N. C. et al. Regulation of histone acetylation in the nucleus by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Science 325, 1254–1257, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1176709 (2009).

Geng, T. et al. SphK1 mediates hepatic inflammation in a mouse model of NASH induced by high saturated fat feeding and initiates proinflammatory signaling in hepatocytes. J Lipid Res 56, 2359–2371, https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.M063511 (2015).

Li, C. et al. Involvement of sphingosine 1-phosphate (SIP)/S1P3 signaling in cholestasis-induced liver fibrosis. Am J Pathol 175, 1464–1472, https://doi.org/10.2353/ajpath.2009.090037 (2009).

Beeler, T. et al. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae TSC10/YBR265w gene encoding 3-ketosphinganine reductase is identified in a screen for temperature-sensitive suppressors of the Ca2+-sensitive csg2Delta mutant. J Biol Chem 273, 30688–30694 (1998).

Boyden, L. M. et al. Mutations in KDSR Cause Recessive Progressive Symmetric Erythrokeratoderma. Am J Hum Genet 100, 978–984, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.05.003 (2017).

Takeichi, T. et al. Biallelic Mutations in KDSR Disrupt Ceramide Synthesis and Result in a Spectrum of Keratinization Disorders Associated with Thrombocytopenia. J Invest Dermatol 137, 2344–2353, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2017.06.028 (2017).

Chu, J. & Sadler, K. C. New school in liver development: lessons from zebrafish. Hepatology 50, 1656–1663, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.23157 (2009).

Holtta-Vuori, M. et al. Zebrafish: gaining popularity in lipid research. The Biochemical journal 429, 235–242, https://doi.org/10.1042/BJ20100293 (2010).

Kim, S. H. et al. A post-developmental genetic screen for zebrafish models of inherited liver disease. PLoS One 10, e0125980, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125980 (2015).

Kihara, A. & Igarashi, Y. FVT-1 is a mammalian 3-ketodihydrosphingosine reductase with an active site that faces the cytosolic side of the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. J Biol Chem 279, 49243–49250, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M405915200 (2004).

Foster, D. W. Malonyl-CoA: the regulator of fatty acid synthesis and oxidation. J Clin Invest 122, 1958–1959 (2012).

Valero, T. Mitochondrial biogenesis: pharmacological approaches. Curr Pharm Des 20, 5507–5509 (2014).

Varanita, T. et al. The OPA1-dependent mitochondrial cristae remodeling pathway controls atrophic, apoptotic, and ischemic tissue damage. Cell Metab 21, 834–844, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2015.05.007 (2015).

Hisano, Y. et al. Maternal and Zygotic Sphingosine Kinase 2 Are Indispensable for Cardiac Development in Zebrafish. J Biol Chem 290, 14841–14851, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.634717 (2015).

Mendelson, K., Lan, Y., Hla, T. & Evans, T. Maternal or zygotic sphingosine kinase is required to regulate zebrafish cardiogenesis. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists 244, 948–954, https://doi.org/10.1002/dvdy.24288 (2015).

Engin, A. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 960, 443–467, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48382-5_19 (2017).

Song, B. J. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and tissue injury by alcohol, high fat, nonalcoholic substances and pathological conditions through post-translational protein modifications. Redox Biol 3, 109–123, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2014.10.004 (2014).

Townsend, D. M., Tew, K. D. & Tapiero, H. The importance of glutathione in human disease. Biomed Pharmacother 57, 145–155 (2003).

Ballatori, N. et al. Glutathione dysregulation and the etiology and progression of human diseases. Biol Chem 390, 191–214, https://doi.org/10.1515/BC.2009.033 (2009).

Kim, S. H. et al. Multi-organ abnormalities and mTORC1 activation in zebrafish model of multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. PLoS Genet 9, e1003563, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003563 (2013).

Hannun, Y. A. & Obeid, L. M. Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9, 139–150, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm2329 (2008).

Choi, S. & Snider, A. J. Sphingolipids in High Fat Diet and Obesity-Related Diseases. Mediators Inflamm 2015, 520618, https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/520618 (2015).

Hu, W. et al. Palmitate increases sphingosine-1-phosphate in C2C12 myotubes via upregulation of sphingosine kinase message and activity. J Lipid Res 50, 1852–1862, https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.M800635-JLR200 (2009).

Longato, L., Tong, M., Wands, J. R. & de la Monte, S. M. High fat diet induced hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance: Role of dysregulated ceramide metabolism. Hepatol Res 42, 412–427, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00934.x (2012).

Shah, C. et al. Protection from high fat diet-induced increase in ceramide in mice lacking plasminogen activator inhibitor 1. J Biol Chem 283, 13538–13548, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M709950200 (2008).

Boini, K. M., Zhang, C., Xia, M., Poklis, J. L. & Li, P. L. Role of sphingolipid mediator ceramide in obesity and renal injury in mice fed a high-fat diet. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 334, 839–846, https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.110.168815 (2010).

Mullen, T. D. et al. Selective knockdown of ceramide synthases reveals complex interregulation of sphingolipid metabolism. J Lipid Res 52, 68–77, https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.M009142 (2011).

Pewzner-Jung, Y. et al. A critical role for ceramide synthase 2 in liver homeostasis: II. insights into molecular changes leading to hepatopathy. J Biol Chem 285, 10911–10923, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.077610 (2010).

Pewzner-Jung, Y. et al. A critical role for ceramide synthase 2 in liver homeostasis: I. alterations in lipid metabolic pathways. J Biol Chem 285, 10902–10910, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.077594 (2010).

Raichur, S. et al. CerS2 haploinsufficiency inhibits beta-oxidation and confers susceptibility to diet-induced steatohepatitis and insulin resistance. Cell Metab 20, 687–695, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2014.09.015 (2014).

Arendt, B. M. et al. Altered hepatic gene expression in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with lower hepatic n-3 and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Hepatology 61, 1565–1578, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27695 (2015).

Grek, C. L., Zhang, J., Manevich, Y., Townsend, D. M. & Tew, K. D. Causes and consequences of cysteine S-glutathionylation. J Biol Chem 288, 26497–26504, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.R113.461368 (2013).

Shang, Y., Siow, Y. L. & Isaak, C. K. & O, K. Downregulation of Glutathione Biosynthesis Contributes to Oxidative Stress and Liver Dysfunction in Acute Kidney Injury. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 9707292, https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/9707292 (2016).

Sekhar, R. V. et al. Deficient synthesis of glutathione underlies oxidative stress in aging and can be corrected by dietary cysteine and glycine supplementation. Am J Clin Nutr 94, 847–853, https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.110.003483 (2011).

Stipanuk, M. H., Dominy, J. E. Jr., Lee, J. I. & Coloso, R. M. Mammalian cysteine metabolism: new insights into regulation of cysteine metabolism. J Nutr 136, 1652S–1659S (2006).

Whillier, S., Raftos, J. E., Chapman, B. & Kuchel, P. W. Role of N-acetylcysteine and cystine in glutathione synthesis in human erythrocytes. Redox Rep 14, 115–124, https://doi.org/10.1179/135100009X392539 (2009).

Bielawski, J. et al. Sphingolipid analysis by high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS). Advances in experimental medicine and biology 688, 46–59 (2010).

Hammad, S. M. et al. Blood sphingolipidomics in healthy humans: impact of sample collection methodology. J Lipid Res 51, 3074–3087, https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.D008532 (2010).

Cinaroglu, A., Gao, C., Imrie, D. & Sadler, K. C. Activating transcription factor 6 plays protective and pathological roles in steatosis due to endoplasmic reticulum stress in zebrafish. Hepatology 54, 495–508, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.24396 (2011).

Landgraf, K. et al. Short-term overfeeding of zebrafish with normal or high-fat diet as a model for the development of metabolically healthy versus unhealthy obesity. BMC Physiol 17, 4, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12899-017-0031-x (2017).

Marjoram, L. et al. Epigenetic control of intestinal barrier function and inflammation in zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112, 2770–2775, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1424089112 (2015).

McCurley, A. T. & Callard, G. V. Characterization of housekeeping genes in zebrafish: male-female differences and effects of tissue type, developmental stage and chemical treatment. BMC Mol Biol 9, 102, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2199-9-102 (2008).

Mendelson, K., Zygmunt, T., Torres-Vazquez, J., Evans, T. & Hla, T. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor signaling regulates proper embryonic vascular patterning. J Biol Chem 288, 2143–2156, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.427344 (2013).

Rahn, J. J., Stackley, K. D. & Chan, S. S. Opa1 is required for proper mitochondrial metabolism in early development. PLoS One 8, e59218, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0059218 (2013).

Tsedensodnom, O., Vacaru, A. M., Howarth, D. L., Yin, C. & Sadler, K. C. Ethanol metabolism and oxidative stress are required for unfolded protein response activation and steatosis in zebrafish with alcoholic liver disease. Dis Model Mech 6, 1213–1226, https://doi.org/10.1242/dmm.012195 (2013).

Vacaru, A. M. et al. Molecularly defined unfolded protein response subclasses have distinct correlations with fatty liver disease in zebrafish. Dis Model Mech 7, 823–835, https://doi.org/10.1242/dmm.014472 (2014).

Townsend, D. M. et al. NOV-002, a glutathione disulfide mimetic, as a modulator of cellular redox balance. Cancer Res 68, 2870–2877, https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5957 (2008).

Manevich, Y., Hutchens, S., Tew, K. D. & Townsend, D. M. Allelic variants of glutathione S-transferase P1-1 differentially mediate the peroxidase function of peroxiredoxin VI and alter membrane lipid peroxidation. Free Radic Biol Med 54, 62–70, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.10.556 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Kenneth Tew for helpful comments about oxidative stress and ER stress in the mutant, Dr. Ashley Cowart for helpful discussion on sphingolipid metabolism, Dr. Ho-Jin Koh for sharing results from high fat-diet mouse liver samples, and MUSC Lipidomics Core Facility for sphingolipids measurements and the Analytical Redox Biochemistry Core for thiol, GSH, and GSSG determination. Supported by National Institutes Health (General Medical Sciences Grants P20GM103542-COBRE in Oxidants, Redox Balance, and Stress Signaling and 1P30GM103339-COBRE in Lipidomics and Pathobiology).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H.K. formulated ideas, designed the project, performed experiments, prepared figures and wrote the manuscript. K.H.P. maintained zebrafish colonies, performed experiments and prepared figures. Z.Y. and J.Z. performed experiments for Fig. 7 and D.T. interpreted data in Fig. 7. S.M.H. interpreted sphingolipid data, reviewed and edited the manuscript. D.R. provided helpful insights and direction around the liver defects identified, reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, KH., Ye, Zw., Zhang, J. et al. 3-ketodihydrosphingosine reductase mutation induces steatosis and hepatic injury in zebrafish. Sci Rep 9, 1138 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-37946-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-37946-0

This article is cited by

-

Sphingolipids: drivers of cardiac fibrosis and atrial fibrillation

Journal of Molecular Medicine (2024)

-

Sphk1 deficiency induces apoptosis and developmental defects and premature death in zebrafish

Fish Physiology and Biochemistry (2023)

-

Sphingolipid lysosomal storage diseases: from bench to bedside

Lipids in Health and Disease (2021)

-

Parallel Reaction Monitoring reveals structure-specific ceramide alterations in the zebrafish

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.