Abstract

This was a nine-year retrospective cohort study to investigate obstetric and perinatal outcomes in a cohort of adolescent girls with twin pregnancies from a major Australian tertiary centre in Brisbane, Australia. The adolescent cohort was aged <19 years and the control group was aged 20–24 years. The total study cohort comprised of 183 women. Of these, the adolescent cohort contained 29 girls (15.8%) and the control group comprised of 154 women (84.2%). Adolescent girls were less likely to delivery via an elective caesarean section compared to women in the control group (10.3% vs. 25.7%, p < 0.001). There were no differences in duration of labour, post-partum haemorrhage or perineal trauma rates. After controlling for the confounding effects of parity, chronicity and birth weight, birth <28 weeks remained significant (aOR 11.20, 95% CI 2.97–42.18, p < 0.001) for the adolescent cohort. There was a higher proportion of adolescents whose babies had an adverse composite perinatal outcome (87.9% vs. 69.5%, OR 3.20 95% CI: 1.40–7.31, p = 0.01) however significance was lost after adjusting for parity, chorionicity, birthweight and gestation at birth (aOR 3.27 95% CI: 0.95–11.31, p = 0.06). Our results show that obstetric and perinatal outcomes for twin pregnancies in teenagers were broadly similar compared to controls although the risk of extreme preterm birth was increased after controlling for confounders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adolescent pregnancy is defined as a pregnancy in girls aged 10–19 years and accounts for approximately 11% of births worldwide1. They are predisposed to obstetric complications such as obstructed labour, genital tract fistulae, postpartum haemorrhage, pre-eclampsia and anaemia1,2,3 more commonly observed in developing countries where rates of adolescent pregnancy are far higher.

Although the available literature on adolescent pregnancy in general is somewhat limited, there is a particular paucity of data of outcomes relating to multiple pregnancy. Regardless of maternal age, twin pregnancy is a risk factor for low birthweight and preterm birth4 as well as a myriad of other maternal complications. The aim of this study was to investigate obstetric and perinatal outcomes in a cohort of twin pregnancies in adolescent girls from an Australian tertiary centre.

Methods

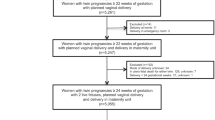

This was a nine-year cohort study of adolescents who birthed at the Mater Mother’s Hospital (MMH) in Brisbane, Australia between 1st January 2007 and 31st December 2015. The adolescent cohort was defined as any female aged 10–19 years and the control group consisted of women aged 20–24 years. Inclusion criteria were non-anomalous twin pregnancies >20 weeks gestation. Ethical, governance and waiver of consent approvals were granted by the Mater Human Research Ethics Committee and Governance and Privacy office (Reference: HREC/14/MHS/37 and RG-14–162) respectively and all methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Socio-economic status was examined via the Socio-Economic Index for Areas (SEIFA) score. In Australia, a SEIFA score in the lowest quartile represents the most disadvantaged demographic group. Obstetric outcomes included onset of labour, mode and indication for birth, length of labour, blood loss and perineal trauma. Perinatal outcomes were gestation at birth, preterm birth, birthweight, birthweight <10th centile (calculated for gestation and sex against Australian birthweight centiles). Serious composite perinatal outcome was defined as severe acidosis at birth (defined as cord pH < 7.1 or lactate >6 mmol/L or base excess <−12mmol/L) or death or admission to the NICU or Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes.

Univariate and multivariable analysis was performed using Generalised Estimating Equations to account for correlation between twins and to calculate odds ratios with 95% Confidence Intervals. Statistical analysis was performed using the Stata statistics program (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Over the study period the total study cohort comprised of 183 women. The adolescent cohort comprised 29 girls (15.8%) and 154 women (84.2%) in the control group. There were 17 (58.6%) dichorionic diamniotic (DCDA) and 12 (41.4%) monochorionic diamniotic (MCDA) twins in the adolescent group and 65 (42.2%) DCDA and 89 (57.8%) MCDA twins in the control group respectively. Compared to the control group, adolescents were more likely to be nulliparous and not be married (Table 1).

After adjusting for parity, chorionicity, birth weight and gestation at birth intrapartum outcomes between the two groups were very similar. (Table 2) Although there were high overall rates of emergency caesarean section in both cohorts with almost one in two adolescent girls requiring this intervention this difference was not significant (48.3% vs. 38.6%, p = 0.17). Adolescent girls were less likely to delivery via an elective caesarean section compared to women in the control group (10.3% vs. 25.7%, p < 0.001). There were no differences in duration of labour, post-partum haemorrhage or perineal trauma rates.

Although adolescent girls had higher rates of preterm birth <32 weeks (48.3% vs. 23.7%, OR 3.00, 95% CI: 1.69–5.36, p < 0.001) and <28 weeks (27.6% vs. 6.2%, OR 5.79, 95% CI: 2.77–12.14, p < 0.001), after controlling for the confounding effects of parity, chronicity and birth weight, only birth <28 weeks remained significant (aOR 11.20, 95% CI 2.97–42.18, p < 0.001). The median gestation at birth and median birth weights were lower in the adolescent cohort compared to controls. However, teenage girls were less likely to deliver a twin infant with birth weight <10th centile. There was a higher proportion of adolescents whose babies had an adverse composite perinatal outcome (87.9% vs. 69.5%, OR 3.20 95% CI: 1.40–7.31, p = 0.01), however significance was lost after adjusting for parity, chorionicity, birthweight and gestation at birth (aOR 3.27 95% CI: 0.95–11.31, p = 0.06). (Table 3) As only 3 adolescents were multiparous we also analysed the data for only the primiparous cohort (Tables 4–6) with essentially similar results.

Discussion

The key finding of this study of multiple pregnancy outcomes in adolescents is the risk of extreme preterm birth (<28 weeks) after controlling for the potentially confounding effects of parity, chorionicity and birthweight. Although there was a higher proportion of neonates with the composite adverse outcome in the adolescent group this did not reach statistical significance after adjusting for confounders. We also found a decreased risk of low birth weight (birth weight < 10th centile for gestation and gender) (aOR 0.41 95% CI: 0.17–0.95, p = 0.04). Although approximately 90% of the adolescent cohort was primiparous, there were no differences in outcomes when this cohort was separately analysed.

There is good evidence that the risk of perinatal death is substantially higher in adolescents compared to women aged 20 to 24 years of age5. One reason for this, is likely to be the higher rates of preterm birth as seen in our study. The causes for the higher rate of birth <28 weeks in the adolescent cohort are not immediately apparent. Furthermore, despite the higher rates of preterm birth in adolescent girls in this study appeared to be less likely to deliver a baby under the 10th centile after controlling for parity and gestation at birth. This is in contrast to outcomes in teenage girls with singletons where there is a higher rate of low birth weight babies6.

Although we demonstrate overall comparable neonatal outcomes for adolescents with twin pregnancies albeit with some specific differences, earlier studies have suggested that rates of adverse outcomes in teenagers are no higher compared to controls7. Although there is evidence showing that overall perinatal outcomes for singletons are poorer in teenagers8 our results suggest that when confounders such as parity, chorionicity and gestation at birth are taken into account, outcomes are also poor in adolescents with multiple pregnancy. It is possible that these poorer pregnancy outcomes may be attributable to the sub-optimal pre-pregnancy health status of teenage girls as well as factors consistent with higher prevalence of poor socio-economic status in this cohort.

We did not observe poorer obstetric or intrapartum outcomes in our study. Overall caesarean section rates were high in both cohorts and there were no differences in total length of labour, rates of perineal trauma or postpartum haemorrhage. This is consistent with other published data7. Adolescents generally have higher rates of pregnancy complications including hypertensive disorders, antepartum haemorrhage, cephalopelvic disproportion and intervention for obstructed labour1,2. Consistent with other studies9 we found lower rates of elective caesarean section in the adolescent cohort suggesting that they were more amenable to attempting a vaginal twin delivery. This is important as there is evidence that adolescent younger mothers are far more likely to have further children in adolescence and thus more children overall in their lifetime10. As adolescents are more likely to develop post-natal mental health issues11 and difficulties with breastfeeding12 which are known to be associated with caesarean birth, any reduction in operative rates could potentially mitigate these important post-partum issues.

While rates of adolescent pregnancy have declined13, complications of pregnancy and childbirth are the second leading cause of death for girls aged 15–19 years old13. As such, the importance of education and universal access to contraception is an important priority in addressing overall disparities in obstetric and perinatal outcomes regardless of the number of fetuses. Indeed, there is evidence to suggest that the risks for adverse pregnancy outcomes in teenage pregnancies can be mitigated by high-quality maternity care14.

The strengths of our study are the inclusion of clinically relevant outcomes and the adjusting for relevant confounders such as chorionicity, parity, gestation at birth and birthweight. The limitations were related to the relatively small number of cases of only 29 teenagers, however the literature is extremely limited with only one paper from 19907 addressing this subject. Although overall, pregnancies in adolescent are not uncommon, multiple pregnancy is and there is a lack of information regarding pregnancy outcomes. We were unable to ascertain termination of pregnancy and miscarriage rates, outcomes that are pertinent to the study cohort. Our results are clinically relevant, highlighting the importance of engaging adolescents and supporting them both during and outside of pregnancy.

References

Ganchimeg, T. et al. Pregnancy and childbirth outcomes among adolescent mothers: a World Health Organization multicountry study. Bjog 121(Suppl 1), 40–48, https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12630 (2014).

Tyrberg, R. B., Blomberg, M. & Kjolhede, P. Deliveries among teenage women - with emphasis on incidence and mode of delivery: a Swedish national survey from 1973 to 2010. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 13, 204, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-13-204 (2013).

Sedgh, G., Finer, L. B., Bankole, A., Eilers, M. A. & Singh, S. Adolescent pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates across countries: levels and recent trends. J Adolesc Health 56, 223–230, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.007 (2015).

Branum, A. M. Teen maternal age and very preterm birth of twins. Matern Child Health J 10, 229–233, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-005-0035-1 (2006).

Fraser, A. M., Brockert, J. E. & Ward, R. H. Association of young maternal age with adverse reproductive outcomes. N Engl J Med 332, 1113–1117, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199504273321701 (1995).

Daniels, S., Robson, D., Flatley, C. & Kumar, S. Demographic characteristics and pregnancy outcomes in adolescents - Experience from an Australian perinatal centre. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 57, 630–635, https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.12651 (2017).

Blake, D. M. & Lee, M. I. Twin pregnancy in adolescents. Obstet Gynecol 75, 172–174 (1990).

Malabarey, O. T., Balayla, J., Klam, S. L., Shrim, A. & Abenhaim, H. A. Pregnancies in young adolescent mothers: a population-based study on 37 million births. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 25, 98–102, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2011.09.004 (2012).

Traisrisilp, K., Jaiprom, J., Luewan, S. & Tongsong, T. Pregnancy outcomes among mothers aged 15 years or less. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 41, 1726–1731, https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.12789 (2015).

Menken, J. The health and social consequences of teenage childbearing. Fam Plann Perspect 4, 45–53 (1972).

Reid, V. & Meadows-Oliver, M. Postpartum depression in adolescent mothers: an integrative review of the literature. J Pediatr Health Care 21, 289–298, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2006.05.010 (2007).

Motil, K. J., Kertz, B. & Thotathuchery, M. Lactational performance of adolescent mothers shows preliminary differences from that of adult women. J Adolesc Health 20, 442–449, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00036-0 (1997).

Ouattara, M., Sen, P. & Thomson, M. Forced marriage, forced sex: the perils of childhood for girls. Gend Dev 6, 27–33, https://doi.org/10.1080/741922829 (1998).

Raatikainen, K., Heiskanen, N., Verkasalo, P. K. & Heinonen, S. Good outcome of teenage pregnancies in high-quality maternity care. Eur J Public Health 16, 157–161, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cki158 (2006).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge research support by the Mater Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K. conceived of the study and wrote the final draft, C.F. performed the statistical analysis, D.R. and S.D. wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Robson, D., Daniels, S., Flatley, C. et al. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes for twin pregnancies in adolescent girls. Sci Rep 8, 18072 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-37364-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-37364-2

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.