Abstract

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome is an infectious disease that causes serious economic losses to the swine industry worldwide. To better understand the pathogenesis of the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), three PRRSV strains with different molecular markers and virulence were used to infect MARC-145 cells. A total of 1804 proteins were identified, and 233 altered proteins and 72 signaling pathways involved in the proteomic profiling of virus-infected MARC-145 cells increased with the virulence of the PRRSV strain. The three types of viral strains shared a common pathway—the electron transport reaction in mitochondria—in the infected-MARC-145 cells. Moreover, the antisense pathway was the most variable of all significant signaling pathways for the highly virulent SX-1 strain, indicating that this unique pathway may be connected to the high virulence of the SX-1 strain. Our study is the first attempt to provide a proteome profile of MARC-145 cells infected with PRRSV strains with different virulence, and these findings will facilitate a deep understanding of the interactions between this virus and its host.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), the causative agent of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS), is an important pathogen in the swine industry, and it causes reproductive failure in pregnant sows and respiratory disorders in pigs of all ages1. As a member of the Arteriviridae family, PRRSV is an enveloped, linear, single positive-stranded RNA virus, and it is similar to the equine arteritis virus, lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus, and simian hemorrhagic fever virus2. PRRSV can be classified into two distinct genotypes: type 1 (European type) and type 2 (North American type)3,4. In vivo, this virus mainly infects pulmonary alveolar macrophages (PAMs)5,6,7, whereas in vitro, MARC-145 cells are a good platform to study viral replication, pathogenesis, and host response8,9,10,11.

In life cycle of cells, there are some natural antisense transcripts (NATs), which are reverse complementarity with mRNAs12. These NATs, also named antisense RNAs or natural regulatory RNAs, are small molecules and non-coding RNAs, mediating regulation and generally inhibiting mRNA transcription and/or translation or inducing their rapid degradation13,14. Signals regarding antisense RNA transcription and regulation were named the antisense pathway, in which PSF (Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein-associated-splicing factor), P54 (Non-POU domain-containing octamer-binding protein) and MATR3 (matrin-3) are major proteins15,16,17. PSF is a DNA- and RNA- binding protein, involved in regulation of signal-induced alternative splicing and homologous DNA pairing18. The PSF-P54 heterodimer associated with MATR3 may play a role in nuclear retention of defective RNAs19. PSF also binds to and represses gene promoter region, such as CTBP1, P53, SMAD3 and P2120,21.

To explore the cellular mechanisms of PRRSV infection, mRNA expression has been analyzed at both molecular and cellular levels11,22. However, mRNA abundance is not always consistent with protein expression levels23. In recent years, proteomics analysis has been used to identify cellular protein expression profiles related to PRRSV infection24,25,26. Most reports of the proteomics analysis of PRRSV have described two-dimensional electrophoresis and mass spectrometry (MS) approaches24,25,27. In this study, we performed isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) labeling coupled with 2D/LC (liquid chromatography)–MS/MS analysis to detect the comparative protein profile of MARC-145 cells infected with different PRRSV strains28. Three differential virulent strains were used in this study, which are all belong to genotypes: type 2. SX-1 was a highly virulent strain which characterized with a 30aa deletion in nonstructural protein 2 (Nsp2) and isolated from domestic pigs in 200829. The moderate virulent ZCYZ strain with a 54aa deletion in Nsp2 was isolated from hybrid wild boars in 200930. The SD1 strain was a classic PRRSV strain with no deletion in Nsp2 which was mild virulent to pigs and isolated from domestic pigs in 200431. This new method provided novel information regarding the proteomics of MARC-145 cells infected with different PRRSV strains.

Experimental Procedures

Cells and Viruses

MARC-145 cells were obtained from Shandong Key Lab of Animal Disease Control and Breeding. PAMs were harvested from 6-week-old clinically healthy piglets that were free of PRRSV, porcine circovirus, and Mycoplasma spp. PAMs were isolated, cultured, and infected as described preciously32. The PRRSV SD1 strain with no deletion in nonstructural protein 2 (Nsp2) was isolated from domestic pigs in 200431, and the SX-1 strain with a 30aa deletion in Nsp2 was isolated from domestic pigs in 200829. The virulence of SX-1 is high in pigs, as verified by animal infection experiments29. The ZCYZ strain with a 54aa deletion in Nsp2 was isolated from hybrid wild boars in 200930. The virulences of the SX-1, ZCYZ, and SD1 strains are high, moderate, and mild, respectively, in pigs, as verified by animal infection experiments29,30,31.

Sample Preparation, Digestion, and Labeling with iTRAQ Reagents

MARC-145 cells were incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in DMEM medium (Gibco, Invitrogen, CA) supplemented with 8% fetal bovine serum (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Cells were inoculated with MOI = 0.1 of the PRRSV SX-1, ZCYZ, or SD1 strain.

After being resuspended, sonicated, and quantified, cell samples were cysteines-blocked and digested with trypsin gold, according to the iTRAQ protocol (Applied Biosystems). The control cells were labeled with iTRAQ tag 118, and the three samples (SX-1-infected, ZCYZ-infected, and SD1-infected cells) were labeled with tags 113, 115, and 121, respectively. The labeled samples were then mixed prior to online 2D LC–MS/MS analysis.

LC-ESI-MS/MS Analysis and Data Analysis

After fractionation through strong cationic exchange using the Shimadzu LC-20AB HPLC pump system, the fraction was resuspended and centrifuged. The peptides were subjected to nanoelectrospray ionization followed by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) in an LTQ Orbitrap Velos (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) coupled online to the HPLC. For MS scans, the m/z (mass–charge ratio) scan range was 350–2000 Da.

Relative quantification and protein identification were performed using ProteinPilotTM software 4.0.8085 with the Paragon algorithm (version 4.0.0.0) as a search engine. Each MS/MS spectrum was searched against a database of primate sequences (NCBInr, taxid9443). All identified proteins were grouped using the ProGroup algorithm (ABI) to minimize redundancy. The bias correction and background correction options were executed.

Gene Ontology, Pathway Analysis, and Protein Signal Network Construction

Protein center software was used to analyze the functional distribution of these identified proteins. Pathway analysis was used to identify significant pathways of the differential genes according to KEGG, BioCarta, and Reatome. Fisher’s exact test and the χ2 test were used to select the significant pathways, and the threshold of significance was defined by P-values and false discovery rate (FDR).

To elucidate the differential protein–protein interactions and the signal transduction during PRRSV infection, signal networks were constructed to analyze the protein networks of MARC-145 cells infected by three PRRSV strains with different virulence. Each differentially expressed protein was analyzed and integrated into the network to elucidate the interactions.

Confirmation of Proteomic Data in MARC-145 Cells and PAMs

Western blot and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were simultaneously performed in MARC-145 cells and PAMs to confirm proteomic data. An equivalent amount of protein was separated using 12% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The fractionated proteins were then transferred electrophoretically to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA) and blocked with TBS-T containing 5% bovine serum albumin at 4 °C overnight. The membranes were stained with goat anti-PSF polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz, CA) at 1:200 dilutions, goat anti-annexin A2 (ANXA2) polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz, CA) at 1:200 dilutions, and mouse anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz, CA) at 1:200 dilutions. After incubation at 37 °C for 1 h, immunoreactive protein bands were visualized with a chemiluminescence subtract using the ECL plus Western blot detection system (Kodak, NY). The quantification of protein blots was performed using Photoshop CS5 (Adobe, San Jose).

Total cellular RNA was extracted from MARC-145 cells or PAMs using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The quantification of RNA was performed with a Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE USA), and 1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TaKaRa, China). cDNA was amplified using the SYBR Premix EX Taq II (TaKaRa, China). The primers used for the amplification of different target cDNAs are listed in Table 1. Quantification of the differences between the groups was performed using the 2−ΔΔCt method. β-actin was used as the normalizing gene to compensate for potential differences in cDNA amounts.

Gene Silencing with siRNA

MARC-145 cells grown to 60–70% confluence in 6-well cell culture plates were transfected with PSF siRNA, using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Briefly, 60 pmol of siRNA was diluted in 250 μL of serum-free OptiMEM medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and 5 μL of Lipofectamine RNAiMAX was diluted in 250 μL of OptiMEM. After incubation for 5 min at room temperature, the diluted RNA and Lipofectamine RNAiMAX were combined and incubated again for 20 min at room temperature. Then, 500 μL of the mixture was added dropwise to each well. The plates were incubated at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator for 8 h, and the mixtures were replaced with fresh complete medium and incubated for an additional 40 h before the silencing efficiency was measured using immunoblotting analysis. Scrambled siRNA was used as a negative control.

Results

PRRSV-Infected MARC-145 Cells and iTRAQ Analysis

After inoculation with PRRSV SX-1, ZCYZ, or SD1 strains of MOI = 0.1, the MARC-145 cells were collected at 48 hpi and used for the iTRAQ experiment. Uninfected MARC-145 cells served as a mock control. After digestion, quantification and labeling were performed according to the iTRAQ protocol (Applied Biosystems)33, and the 4-plex iTRAQ experiments were conducted.

Gene Ontology and Pathway and Protein Signal Network Analyses

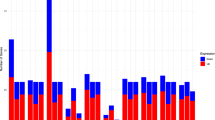

Functional annotation of the 1804 identified proteins was initially performed using the Protein Center software. A P-value of <0.05 and an FDR of <0.05 in a two-sided Fisher’s exact test were selected as significant criteria. Three main types of annotations were obtained from the gene ontology consortium website: cellular components, molecular function, and biological distribution (Fig. 1). A number of the identified proteins were involved in cellular and metabolic processes and biological regulation. Moreover, the molecular function of the identified proteins was associated with binding and catalytic activity. A total of 233 differentially expressed proteins were discovered in this study. Furthermore, 105 proteins were identified as differentially expressed in Group I (SX-1 vs. MARC-145), including 46 upregulated proteins and 59 downregulated proteins (Table 2); 84 proteins were identified as differentially expressed in Group II (ZCYZ vs. MARC-145), including 59 upregulated proteins and 25 downregulated proteins (Table 3); and 44 proteins were identified as differentially expressed in Group III (SD1 vs. MARC-145), including 25 upregulated proteins and 19 downregulated proteins (Table 4). In the three groups, the upregulated and downregulated differential proteins involved in significant pathways were sorted through the enrichment of signaling pathway categories (Fig. 1).

In Group I (SX-1 vs. MARC-145), the significant signaling pathways of upregulated proteins included the antisense pathway, caspase cascade in apoptosis, TNFR1 signaling pathway, FAS signaling pathway (CD95), integrin signaling pathway, HIV-1 Nef: negative effector of Fas and TNF, etc. (Fig. 2A). By contrast, the significant pathways of the downregulated proteins included the mTOR signaling pathway, mechanism of gene regulation by peroxisome proliferators via PPARa (alpha), Ahr signal transduction pathway, oxidative reactions of the pentose phosphate pathway, malate–aspartate shuttle, etc. (Fig. 2B). In Group II (ZCYZ vs. MARC-145), the significant pathways corresponding to the upregulated proteins included the proteasome complex, citric acid cycle, regulation and function of ChREBP in the liver, opposing roles of AIF in apoptosis and cell survival, shuttle for transfer of acetyl groups from mitochondria to the cytosol, etc. (Fig. 2C). The significant pathways of the downregulated proteins were the regulation of spermatogenesis by CREM, Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) Receptor Ptc1 regulates cell cycle, CBL-mediated ligand-induced downregulation of EGF receptors, role of the PI3K subunit p85 in the regulation of actin organization and cell migration, Rac 1 cell motility signaling pathway, etc. (Fig. 2D). In Group III (SD1 vs. MARC-145), the significant pathways corresponding to upregulated proteins included the caspase cascade in apoptosis, TNFR1 signaling pathway, FAS signaling pathway (CD95), HIV-I Nef: negative effector of Fas and TNF, SARS-coronavirus life cycle, and glycolysis pathway (Fig. 2E). The significant pathways of the downregulated proteins included CARM1 and regulation of the estrogen receptor, Pelp1 modulation of estrogen receptor activity, electron transport reaction in mitochondria, and downregulation of MTA-3 in ER-negative breast tumors (Fig. 2F).

Enriched signaling pathway categories of differentially expressed proteins from three groups. (A) Significant signaling pathways of upregulated proteins in Group I. (B) Significant signaling pathways of downregulated proteins in Group I. (C) Significant signaling pathways of upregulated proteins in Group II. (D) Significant signaling pathways of downregulated proteins in Group II. (E) Significant signaling pathways of upregulated proteins in Group III. (F) Significant signaling pathways of downregulated proteins in Group III. ACADVL: very long-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase; ACAT1: acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase; ACO2: Aconitate hydratase; ACSL3: Long-chain-fatty-acid–CoA ligase 3; AHCY: Adenosylhomocysteinase; AHNAK: Neuroblast differentiation-associated protein; AIMP1: Aminoacyl tRNA synthase complex-interacting multifunctional protein 1; AKR1C3: Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C3; ALDH1A1: retinal dehydrogenase 1; ALDOA: Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A; ANXA6: Annexin A6; ARL6IP5: PRA1 family protein 3; ATP5A1: ATP synthase subunit alpha; ATP5D: ATP synthase subunit delta; C14orf142: EKC/KEOPS complex subunit; C16orf80: Cilia- and flagella-associated protein 20; C9orf64: Queuosine salvage protein; CAND1: Cullin-associated NEDD8-dissociated protein 1; CAPN1: Calpain-1 catalytic subunit; CCT3: T-complex protein 1 subunit gamma; CCT8: T-complex protein 1 subunit theta; CKAP4: Cytoskeleton-associated protein 4; CLIC4: Chloride intracellular channel protein 4; CLTC: Clathrin heavy chain 1; COPG: Coatomer subunit gamma; CS: Citrate synthase; CSE1L: Exportin-2; CYCS: Cytochrome c, somatic; DDX3X: ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX3X; DDX3Y: ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX3Y; DDX58: Probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX58; DLST: Dihydrolipoyllysine-residue succinyltransferase component of 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex; DNM1L: Dynamin-1-like protein; ECHS1: Enoyl-CoA hydratase; EEF1G: Elongation factor 1-gamma; EEF2: Eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase; EIF3A: Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit A; EIF3E: Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit E; EPRS: Bifunctional glutamate/proline–tRNA ligase; ERH: Enhancer of rudimentary homolog; FASN: Fatty acid synthase; FLNA: Filamin-A; FLNB: Filamin-B; FLNC: Filamin-C; FUS: RNA-binding protein FUS; G6PD: Glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase; GAPDH: lyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GART: Trifunctional purine biosynthetic protein adenosine-3; GBP1: Guanylate-binding protein 1; GFPT1:Glutamine–fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase [isomerizing] 1; GNA12: Guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit alpha-12; HABP4: Intracellular hyaluronan-binding protein 4; HADH: Hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase; HERC4: Probable E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase HERC4; HIST1H3A: Histone H3.1; HNRNPA2B1: Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins A2/B1; HNRNPAB: Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A/B; HNRNPCL1: Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C-like 1; HNRNPM: Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein M; HNRNPU: Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U; HNRNPUL2: Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U-like protein 2; HSP90AA1: Heat shock protein HSP 90-alpha; HSPA2: Heat shock-related 70 kDa protein 2; HSPA8: Heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein; HSPD1: 60 kDa heat shock protein; HSPE1: 10 kDa heat shock protein IARS: Isoleucine–tRNA ligase; IGF2BP3: Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 3; ILF3: Interleukin enhancer-binding factor 3; IMMT: MICOS complex subunit MIC60; INTS5: Integrator complex subunit 5; IPO7: Importin-7; ITGB1: Integrin beta-1; KHSRP: Far upstream element-binding protein 2; KRT18: Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 18; LMNA: Prelamin-A/C; LMNB2: Lamin-B2; MANF: Mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor; MATR3: Matrin-3; MDH1: Malate dehydrogenase; MDH2: Malate dehydrogenase; MKI67: Proliferation marker protein Ki-67; MMS19: MMS19 nucleotide excision repair protein homolog; MRPS17: 28S ribosomal protein S17; MTOR: Serine/threonine-protein kinase mTOR; MYL6B: Myosin light chain 6B; MYO1B: Unconventional myosin-Ib; MYO1C: Unconventional myosin-Ic; NAP1L4: Nucleosome assembly protein 1-like 4; NASP: Nuclear autoantigenic sperm protein; NCL: Nucleolin; NCSTN: Nicastrin; NDRG1: N-myc downstream-regulated gene 1 protein; NME2: Nucleoside diphosphate kinase B; NPC2: NPC intracellular cholesterol transporter 2; NT5C2: Cytosolic purine 5′-nucleotidase; NUDT1: 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine triphosphatase; P4HA1: Prolyl 4-hydroxylase subunit alpha-1; P54: Non-POU domain-containing octamer-binding protein(NONO); PAFAH1B3: Platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase IB subunit gamma; PCK2: Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase [GTP]; PCNA: PCNA-associated factor; PDCD11: Protein RRP5 homolog; PDCD5: Programmed cell death protein 5; PDGFRA: Platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha; PDIA3: Protein disulfide-isomerase A3; PDIA4: Protein disulfide-isomerase A4; PDIA6: Protein disulfide-isomerase A6; PELP1: Proline-, glutamic acid- and leucine-rich protein 1; PGK1: Phosphoglycerate kinase 1; PGM1: Phosphoglucomutase-1; PHB: Prohibitin; PHB2: Prohibitin-2; POLR2B: DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit RPB2; PPP5C: Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 5; PRDX6: Peroxiredoxin-6; PRPF8: Pre-mRNA-processing-splicing factor 8; PSAP: Prosaposin; PSF: Splicing factor, proline- and glutamine-rich(SFPQ); PSMA1: Proteasome subunit alpha type-1; PSMA2: Proteasome subunit alpha type-2; PSMA7: Proteasome subunit alpha type-7; PSMB4: Proteasome subunit beta type-4; PSMD1: 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 1; PTBP1: Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 1; RALY: RNA-binding protein Raly; RARS: Arginine-tRNA ligase; RBMX: RNA-binding motif protein, X chromosome; RPL10: 60S ribosomal protein L10; RPL10A: 60S ribosomal protein L10-1; RPL24: 60S ribosomal protein L24; RPL27: 60S ribosomal protein L27; RPL5: 60S ribosomal protein L5; RPLP0: 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0; RPS20: 40S ribosomal protein S20; RPS21: 40S ribosomal protein S21; RPS25: 40S ribosomal protein S25; RPS3: 40S ribosomal protein S3; RPSA: 30S ribosomal protein S1; RSL1D1: Ribosomal L1 domain-containing protein 1; RTCD1: RNA 3′-terminal phosphate cyclase; SEC. 22B: Vesicle-trafficking protein SEC. 22b; SF3A1: Splicing factor 3A subunit 1; SF3B2: Splicing factor 3B subunit 2; SMARCC1: WI/SNF-related matrix-associated actin-dependent regulator of chromatin subfamily C member 1; SOS1: Son of sevenless homolog 1; SOS2: Son of sevenless homolog 2; SP1: Transcription factor Sp1; SPARC: Basement-membrane protein 40; SSB: Lupus La protein; SYNCRIP: Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein Q; TALDO1: Transaldolase; TCP1: T-complex protein 1 subunit alpha; TLN1: Talin-1; TOMM5: Mitochondrial import receptor subunit TOM5 homolog; TUBA1A: Tubulin alpha-1A chain; TXN: Thioredoxin; UBR5: E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase UBR5; VAV3: Guanine nucleotide exchange factor VAV3; VCL: Vinculin; VIM: Vimentin; WARS: Tryptophan–tRNA ligase; XPO1: Exportin-1; YWHAE: 14-3-3 protein epsilon; YWHAZ: 14-3-3 protein zeta/delta.

A signaling network was used to establish possible interactions among the differentially expressed proteins. In MARC-145 cells infected with SX-1, the most central proteins are NCL, RPLPO, HSPD1, RPS3, HSPA8, P54, HNRNPM, TCP1, VIM, HSP90AA1, MATR3, SYNCRIP, YMHAE, EEF1G, FLNA, HNRNPA2B1, PTBP1, ATP5A1, CCT3, RBMX, CCT8, ANXA2, CLTC, HNRNPU, LMNA, AHNAK, and FLNB (Fig. 3A). In MARC-145 cells infected with ZCYZ, the most central proteins included HSPA8, DDX3X, ATP5A1, YWHAE, EEF2, YWHAZ, GAPDH, HNRNPA2B1, SYNCRIP, ANXA2, HNRNPM, RPL18A, FLNB, and PHB (Fig. 3B). In MARC-145 cells infected with SD1, NCL, DDX3X, FASN, FLNA, HSPA8, PGK1, ANXA2, RBMX, ATP5A1, HNRNPAB, and LMNA exhibited as the most central proteins (Fig. 3C). These proteins tended to be more essential than noncentral proteins in the modular organization of the protein–protein interaction network.

Signaling networks of differentially expressed proteins. (A) Signaling networks of differentially expressed proteins in Group I. (B) Signaling networks of differentially expressed proteins in Group II. (C) signaling networks of differentially expressed proteins in Group III. Upregulated proteins are shown in red, whereas downregulated proteins are shown in blue. Circle sizes represent the capacity of a protein to interact with other proteins, which is quantified in degrees. The greater degree a protein has, the more altered proteins interact with it. SFPQ and NONO are the synonyms of PSF and P54, respectively.

Confirmation of Proteomic Data

To validate the findings of differentially expressed proteins identified by the iTRAQ labeled LC–MS/MS system, PSF and ANXA2 were analyzed using Western blotting (Fig. 4A), and β-actin was used as an internal control. The results revealed that PSF was upregulated in both MARC-145 cells and PAMs infected with SX-1 at 48 hpi, whereas Annexin A2 was downregulated in both MARC-145 cells and PAMs infected with SX-1 at 48 hpi. Further quantitative analyses demonstrated that PSF and ANXA2 expression significantly differed between the PRRSV-infected and control groups (Fig. 4B). Similar results were obtained from the quantitative real-time PCR assay (Fig. 4C). Taken together, the Western blotting and quantitative real-time PCR results were consistent with those of the iTRAQ-coupled 2D LC–MS/MS analysis.

Confirmation of proteomic data by Western blot and real-time PCR. (A) MARC-145 cells and PAMs infected with SX-1 at 48 hpi were harvested and lysed; then, cell extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed through immunoblotting with anti-HSPA8 and anti-ANXA2 antibodies. β-actin was used as a protein loading control. (B) Representative results are shown in a graph representing the density ratio to β-actin normalized to the control condition. (C) A graph of the quantified transcript levels of MARC-145 cells and PAMs infected with SX-1. Gene expression was quantified using real-time PCR and the comparative critical threshold (2−ΔΔCt) method. The β-actin gene was used as the endogenous reference. Three independent experiments were performed. The data from three independent trails are represented as mean ± SD. t-test; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Knockdown of Endogenous PSF Genes Decreases Replication of the PRRSV SX-1 Strain

The PSF protein is associated with various functions, including RNA splicing, viral replication, genetic recombination, and cancer suppression34,35,36. After SX-1 infection, PSF protein expression levels were increased. To clarify the function of PSF in the viral replication cycle, the effect of decreasing the amount of intracellular PSF on the replication of PRRSV was further examined using target-specific RNA interference. Therefore, MARC-145 cells were transfected with PSF siRNA duplexes designed to specifically silence the expression of the PSF gene. As shown in Fig. 5A, MARC-145 cells transfected with PSF siRNA exhibited an approximately 82% decreased level of endogenous PSF protein compared with the cells transfected with scrambled, noneffective siRNAs (Fig. 5B). The reduction in PSF protein concentration resulted in a significant decrease in viral yield through the TCID50 quantitative method; particularly, a 12.7-fold decrease at 60 hpi was observed in SiPSF-transfected groups compared with scramble-transfected groups (Fig. 5C). However, no significant effect on the viral yield of the ZCYZ or SD1 strains was noted, indicating that PSF has a different effect on the various virulent strains of PRRSV. Taken together, these results revealed that PSF has a unique upregulated expression and is required for the effective infection of the highly virulent PRRSV SX-1 strain.

Knockdown of Endogenous PSF Genes Decreases Replication of the PRRSV SX-1 Strain. (A) Endogenous PSF protein expression was down-regulated by PSF siRNA (SiPSF). SiRNA was transfected by Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Scrambled siRNA was used as a negative control. After transfected 48 h, cells were harvested, and western blotting was performed. (B) Graphical representation of t-test of the ratios of density between the PSF and β-actin bands. ****p < 0.0001. (C) After siPSF was transfected 48 h, virus was incubated of MOI = 0.1. The growth curves of viruses were drawn by assaying the viral titers of the supernatants obtained from 12 h to 72 h post infection by using microtitration infectivity assays. The data from three independent trails are represented as mean ± SD. t-test; *p < 0.05.

Discussion

Understanding the changes in cellular protein levels after exposure to PRRSV is helpful for elucidating the molecular mechanism associated with functional alterations. We were, in this study, the first to apply an iTRAQ-2D LC–MS/MS method for the proteome profiling of MARC-145 cells infected with PRRSV strains with different virulence. The functional roles of the differentially expressed proteins associated with PRRSV infection are discussed as follows.

In Group I (SX-1 vs. MARC-145), the differentially expressed proteins were mostly involved in morphogenesis, protein synthesis, metabolism, stress response, the receptor complex, and endocytosis. FLNB, FLNA, LMNA, and LMNB1 were supposed to involve an alteration of cytoskeletal networks and cellular communication. HSPD1, HSPA8, HSP90AA1, and HSPE1 were related to stress response37. In addition, they acted as molecular chaperones facilitating the assembly of multiprotein complexes, participating in the translocation of polypeptides across cell membranes and to the nucleus, and aiding in the proper folding of nascent polypeptide chains. HSPA8, also known as HSP70, is mainly found in both the cytosol and nucleus of mammalian cells, playing key roles in the cytosolic endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial import machinery38. The upregulated expression of HSP70 can protect PRRSV-infected MARC-145 cells against apoptosis and be conducive to the replication and spread of the virus, indicating that HSP70 is associated with the pathogenesis of this virus. As a member of the annexin family, ANXA2 is highly expressed in eukaryotic cells and localizes in the cytosol39. Precious reports have implicated ANXA2 in the replication of certain viruses39,40,41. Regarding PRRSV, ANXA2 can interact with the PRRSV Nsp9 protein and be incorporated into virions42. Importantly, ANXA2 is beneficial for PRRSV replication in vitro43. The cytoskeleton protein of vimentin (VIM) acts as the receptor complex of PRRSV and forms a complex with Nsp2 by using the viral N protein as an intermediate44,45. CLTC (clathrin) is a major protein component of the cytoplasmic face of intracellular organelles, the so-called coated vesicles and coated pits. It has been reported that the entry of PRRSV into cells occurs by specific binding to the outer cell membrane, followed by clathrin-dependent endocytosis. First, the PRRS virions bind to cell-surface receptors; then, they are delivered intact into the endosome through clathrin-coated pits and vesicles. The entire process was demonstrated and proven using confocal microscopy46,47,48.

In Group II (ZCYZ vs. MARC-145), an interesting discovery that differed from other groups was that the expressed proteins, including PSMA1, PSMA2, PSMA7, PSMB4, and PSMD1, were involved in the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (UPP). This pathway is the major nonlysosomal process responsible for the breakdown of most short-lived and long-lived proteins in mammalian cells. In addition, this pathway controls various major biological events—avoidance of host immune surveillance, viral maturation and viral progeny release, oncogenesis, transcriptional control, signal transduction, receptor downregulation, and antigen processing—via the breakdown of specific proteins49. Many viruses have been reported to evolve different strategies to utilize this pathway for their own benefits. For example, the ubiquitin–proteasome system has been suggested to be required for p53 inactivation, apoptosis suppression, viral transcription, and regulation of the human T-cell leukemia virus 150,51. Adenovirus and coronavirus can also make use of the UPP for ubiquitination52,53. Recently, the ovarian tumor domain of PRRSV Nsp2 was reported to possess ubiquitin-deconjugating activity, which inhibits NF-κB activation through the prevention of iκBα degradation by interfering with its polyubiquitination process54. Nsp11 protein, which has a unique and conserved endoribonuclease, inhibits NF-κB activation by specifically removing lysine 48 (K48)-linked polyubiquitin chains55.

In Group III (SD1 vs. MARC-145), only 44 differentially expressed proteins, which was the smallest number among the three groups, were found in the MARC-145 cells infected with a mild virulent SD1 strain. These differentially expressed proteins were mainly related to cell morphology, protein synthesis and metabolism, heat stress response, etc. The central proteins included NCL, DDX3X, FASN, FLNA, HSPA8, and ANXA2. NCL (also called nucleolin) is a type of cellular skeleton protein with the primary function of binding with proteins and nucleic acids. DDX3X is an ATP-dependent RNA helicase that has ATP-binding activity, nucleic acid- and protein-binding activity, and helicase activity. It is mainly involved in species interactions. FASN is mainly related to fatty acid and energy metabolism. FLNA (filament protein A), a skeleton protein in cells, not only has the ability to bind with proteins, nucleic acids, and transcription factors but also possesses the function of signal transduction.

Antisense RNAs, also referred to as natural antisense transcripts or natural regulatory RNAs, are small molecules that mediate regulation and generally inhibit mRNA transcription and/or translation or induce their rapid degradation13,14. Signals regarding antisense RNA transcription and regulation were named the antisense pathway, in which PSF and P54 are major proteins15,16,17. After infection with the PRRSV SX-1 strain, PSF and P54 protein expression was upregulated (Fig. 2A), and the antisense pathway was the most variable of all the significant signaling pathways for the highly virulent SX-1 strain; however, this finding was not observed in the signaling pathways for the moderately virulent ZCYZ strain or the mildly virulent SD1 strain (Fig. 2A). Hence, target-specific RNA interference was used to decrease endogenous PSF protein levels to verify its function in PRRSV infection. After decreasing PSF protein concentration, the viral yield of SX-1 significantly decreased, whereas the viral yield of the ZCYZ and SD1 strains were not significantly affected (Fig. 5), indicating that PSF protein has different functions in various virulent PRRSV strains. As a major protein of the antisense pathway, the silencing of PSF expression is expected to affect antisense pathway function. Accordingly, the molecular mechanism of PSF and antisense pathway function in the infection of different virulent PRRSV strains will be assessed in further research.

Conclusions

We displayed the “colorful” proteome profile of MARC-145 cells infected with different PRRSV strains using the iTRAQ coupled with 2D LC–MS/MS approach for the first time. A total of 233 significantly altered proteins were identified, and we proved that PSF protein has different functions in various virulent PRRSV strains. The study provided an abundance of useful information to study the diversification of MARC-145 cells infected with different PRRSV strains, and these data would help to understand the interactions between this virus and its host.

References

Albina, E. Epidemiology of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS): an overview. Veterinary microbiology 55, 309–316 (1997).

Cavanagh, D. Nidovirales: a new order comprising Coronaviridae and Arteriviridae. Arch Virol 142, 629–633 (1997).

Nelsen, C. J., Murtaugh, M. P. & Faaberg, K. S. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus comparison: divergent evolution on two continents. J Virol 73, 270–280 (1999).

Stadejek, T. et al. Identification of radically different variants of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in Eastern Europe: towards a common ancestor for European and American viruses. J Gen Virol 83, 1861–1873, https://doi.org/10.1099/0022-1317-83-8-1861 (2002).

Wensvoort, G. et al. Mystery swine disease in The Netherlands: the isolation of Lelystad virus. Vet Q 13, 121–130 (1991).

Rossow, K. D. et al. Chronological immunohistochemical detection and localization of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in gnotobiotic pigs. Veterinary pathology 33, 551–556, https://doi.org/10.1177/030098589603300510 (1996).

Duan, X., Nauwynck, H. J. & Pensaert, M. B. Virus quantification and identification of cellular targets in the lungs and lymphoid tissues of pigs at different time intervals after inoculation with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV). Veterinary microbiology 56, 9–19, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1135(96)01347-8 (1997).

Benfield, D. A. et al. Characterization of swine infertility and respiratory syndrome (SIRS) virus (isolate ATCC VR-2332). Journal of veterinary diagnostic investigation: official publication of the American Association of Veterinary Laboratory Diagnosticians, Inc 4, 127–133, https://doi.org/10.1177/104063879200400202 (1992).

Kim, H. S., Kwang, J., Yoon, I. J., Joo, H. S. & Frey, M. L. Enhanced replication of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus in a homogeneous subpopulation of MA-104 cell line. Arch Virol 133, 477–483 (1993).

Wensvoort, G. et al. Lelystad virus, the cause of porcine epidemic abortion and respiratory syndrome: a review of mystery swine disease research at Lelystad. Veterinary microbiology 33, 185–193 (1992).

Genini, S. et al. Genome-wide transcriptional response of primary alveolar macrophages following infection with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J Gen Virol 89, 2550–2564, https://doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.2008/003244-0 (2008).

Khorkova, O., Myers, A. J., Hsiao, J. & Wahlestedt, C. Natural antisense transcripts. Human molecular genetics 23, R54–63, https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddu207 (2014).

Hamilton, A. J. & Baulcombe, D. C. A species of small antisense RNA in posttranscriptional gene silencing in plants. Science 286, 950–952 (1999).

Katayama, S. et al. Antisense transcription in the mammalian transcriptome. Science 309, 1564–1566, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1112009 (2005).

Chen, L. L. & Carmichael, G. G. Decoding the function of nuclear long non-coding RNAs. Current opinion in cell biology 22, 357–364, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceb.2010.03.003 (2010).

Wang, X., Song, X., Glass, C. K. & Rosenfeld, M. G. The long arm of long noncoding RNAs: roles as sensors regulating gene transcriptional programs. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 3, a003756, https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a003756 (2011).

Zolotukhin, A. S. et al. PSF acts through the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mRNA instability elements to regulate virus expression. Molecular and cellular biology 23, 6618–6630 (2003).

Zhang, Z. & Carmichael, G. G. The fate of dsRNA in the nucleus: ap54(nrb)-containing complex mediates the nuclear retention of promiscuously A-to-I edited RNAs. Cell 106, 465–475 (2001).

Salton, M., Lerenthal, Y., Wang, S. Y., Chen, D. J. & Shiloh, Y. Involvement of Matrin 3 and SFPQ/NONO in the DNA damage response. Cell cycle 9, 1568–1576, https://doi.org/10.4161/cc.9.8.11298 (2010).

Takayama, K. et al. Androgen-responsive long noncoding RNA CTBP1-AS promotes prostate cancer. The EMBO journal 32, 1665–1680, https://doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2013.99 (2013).

Takayama, K. I. et al. Dysregulation of spliceosome gene expression in advanced prostate cancer by RNA-binding protein PSF. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114, 10461–10466, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1706076114 (2017).

Zhang, X., Shin, J., Molitor, T. W., Schook, L. B. & Rutherford, M. S. Molecular responses of macrophages to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection. Virology 262, 152–162, https://doi.org/10.1006/viro.1999.9914 (1999).

Lahtvee, P. J. et al. Absolute Quantification of Protein and mRNA Abundances Demonstrate Variability in Gene-Specific Translation Efficiency in Yeast. Cell systems 4, 495–504 e495, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2017.03.003 (2017).

Lu, Q. et al. Two-dimensional liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry coupled with isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ) labeling approach revealed first proteome profiles of pulmonary alveolar macrophages infected with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Journal of proteome research 11, 2890–2903, https://doi.org/10.1021/pr201266z (2012).

Xiao, S. et al. Proteome changes of lungs artificially infected with H-PRRSV and N-PRRSV by two-dimensional fluorescence difference gel electrophoresis. Virol J 7, 107, https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-7-107 (2010).

Genini, S. et al. Identification of serum proteomic biomarkers for early porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) infection. Proteome science 10, 48, https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-5956-10-48 (2012).

Zhang, H. et al. Changes in the cellular proteins of pulmonary alveolar macrophage infected with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus by proteomics analysis. Journal of proteome research 8, 3091–3097, https://doi.org/10.1021/pr900002f (2009).

Ross, P. L. et al. Multiplexed protein quantitation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using amine-reactive isobaric tagging reagents. Molecular & cellular proteomics: MCP 3, 1154–1169, https://doi.org/10.1074/mcp.M400129-MCP200 (2004).

Yu, J. et al. Concurrent highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection accelerates Haemophilus parasuis infection in conventional pigs. Veterinary microbiology 158, 316–321, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.03.001 (2012).

Wu, J. et al. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome in hybrid wild boars, china. Emerging infectious diseases 17, 1071–1073, https://doi.org/10.3201/eid/1706.101518 (2011).

Wu, J. et al. Genetic variation and pathogenicity of highly virulent porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus emerging in China. Arch Virol 154, 1589–1597, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-009-0478-6 (2009).

Chiou, M. T., Jeng, C. R., Chueh, L. L., Cheng, C. H. & Pang, V. F. Effects of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (isolatetw91) on porcine alveolar macrophages in vitro. Veterinary microbiology 71, 9–25 (2000).

Wiese, S., Reidegeld, K. A., Meyer, H. E. & Warscheid, B. Protein labeling by iTRAQ: a new tool for quantitative mass spectrometry in proteome research. Proteomics 7, 340–350, https://doi.org/10.1002/pmic.200600422 (2007).

Shav-Tal, Y. & Zipori, D. PSF andp54(nrb)/NonO–multi-functional nuclear proteins. FEBS letters 531, 109–114 (2002).

Greco-Stewart, V. S., Thibault, C. S. & Pelchat, M. Binding of the polypyrimidine tract-binding protein-associated splicing factor (PSF) to the hepatitis delta virus RNA. Virology 356, 35–44, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2006.06.040 (2006).

Yang, P. et al. Long noncoding RNA GAPLINC promotes invasion in colorectal cancer by targeting SNAI2 through binding with PSF and NONO. Oncotarget 7, 42183–42194, https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.9741 (2016).

Korfanty, J. et al. Crosstalk between HSF1 and HSF2 during the heat shock response in mouse testes. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 57, 76–83, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2014.10.006 (2014).

Gragerov, A. & Gottesman, M. E. Different peptide binding specificities of hsp70 family members. J Mol Biol 241, 133–135, https://doi.org/10.1006/jmbi.1994.1482 (1994).

Saxena, V., Lai, C. K., Chao, T. C., Jeng, K. S. & Lai, M. M. Annexin A2 is involved in the formation of hepatitis C virus replication complex on the lipid raft. J Virol 86, 4139–4150, https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.06327-11 (2012).

Backes, P. et al. Role of annexin A2 in the production of infectious hepatitis C virus particles. J Virol 84, 5775–5789, https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02343-09 (2010).

Yang, S. L., Chou, Y. T., Wu, C. N. & Ho, M. S. Annexin II binds to capsid protein VP1 of enterovirus 71 and enhances viral infectivity. J Virol 85, 11809–11820, https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00297-11 (2011).

Zhang, C. et al. Profiling of cellular proteins in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus virions by proteomics analysis. Virol J 7, 242, https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-7-242 (2010).

Li, J. et al. The interaction between host Annexin A2 and viral Nsp9 is beneficial for replication of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virus Res 189, 106–113, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2014.05.015 (2014).

Song, T. et al. Quantitative interactome reveals that porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nonstructural protein 2 forms a complex with viral nucleocapsid protein and cellular vimentin. Journal of proteomics 142, 70–81, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2016.05.009 (2016).

Zhang, Q. & Yoo, D. PRRS virus receptors and their role for pathogenesis. Veterinary microbiology 177, 229–241, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.04.002 (2015).

Van Breedam, W. et al. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus entry into the porcine macrophage. J Gen Virol 91, 1659–1667, https://doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.020503-0 (2010).

Van Gorp, H., Van Breedam, W., Delputte, P. L. & Nauwynck, H. J. The porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus requires trafficking through CD163-positive early endosomes, but not late endosomes, for productive infection. Arch Virol 154, 1939–1943, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-009-0527-1 (2009).

Cai, Y. et al. Simian hemorrhagic fever virus cell entry is dependent on CD163 and uses a clathrin-mediated endocytosis-like pathway. J Virol 89, 844–856, https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02697-14 (2015).

Gao, G. & Luo, H. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in viral infections. Canadian journal of physiology and pharmacology 84, 5–14, https://doi.org/10.1139/y05-144 (2006).

Yew, P. R. & Berk, A. J. Inhibition of p53 transactivation required for transformation by adenovirus early 1B protein. Nature 357, 82–85, https://doi.org/10.1038/357082a0 (1992).

Peloponese, J. M. Jr. et al. Ubiquitination of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 tax modulates its activity. J Virol 78, 11686–11695, https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.78.21.11686-11695.2004 (2004).

Balakirev, M. Y., Jaquinod, M., Haas, A. L. & Chroboczek, J. Deubiquitinating function of adenovirus proteinase. J Virol 76, 6323–6331 (2002).

Sulea, T., Lindner, H. A., Purisima, E. O. & Menard, R. Deubiquitination, a new function of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus papain-like protease? J Virol 79, 4550–4551, https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.79.7.4550-4551.2005 (2005).

Sun, Z., Chen, Z., Lawson, S. R. & Fang, Y. The cysteine protease domain of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nonstructural protein 2 possesses deubiquitinating and interferon antagonism functions. J Virol 84, 7832–7846, https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00217-10 (2010).

Wang, D. et al. The nonstructural protein 11 of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus inhibits NF-kappaB signaling by means of its deubiquitinating activity. Mol Immunol 68, 357–366, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molimm.2015.08.011 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Fund [grant number 31602076, 31572550, 31340047], Shandong Natural Science Fund [grant number ZR2015YL076, BS2014NY009], Shandong Modern Agricultural Technology & Industry System [grant number SDAIT-08-06], Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences Projects [grant number 2014CGPY04, CXGC2016B14] and Taishan Scholars Project [grant number ts201511069]. The authors thanked Dr. Bindong Liu of Meharry Medical College and Dr. Xiang Mao of Nanjing Agricultural University for their helpful advice and revisions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhi Chen, Shaoning Liu and Jiaqiang Wu designed experiments; Zhi Chen, Shujin Zhang, Yuyu Zhang and Jiang Yu carried out experiments; Wenbo sun, Lei Chen, Yijun Du, Jinbao Wang and Yubao Li analyzed experiment results; Zhi Chen and Shaoning Liu wrote and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Z., Liu, S., Zhang, S. et al. Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus strains with Higher Virulence Cause Marked Protein Profile Changes in MARC-145 Cells. Sci Rep 8, 15000 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32984-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32984-0

Keywords

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.