Abstract

The jerantinine family of Aspidosperma indole alkaloids from Tabernaemontana corymbosa are potent microtubule-targeting agents with broad spectrum anticancer activity. The natural supply of these precious metabolites has been significantly disrupted due to the inclusion of T. corymbosa on the endangered list of threatened species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. This report describes the asymmetric syntheses of (−)-jerantinines A and E from sustainably sourced (−)-tabersonine, using a straight-forward and robust biomimetic approach. Biological investigations of synthetic (−)-jerantinine A, along with molecular modelling and X-ray crystallography studies of the tubulin—(−)-jerantinine B acetate complex, advocate an anticancer mode of action of the jerantinines operating via microtubule disruption resulting from binding at the colchicine site. This work lays the foundation for accessing useful quantities of enantiomerically pure jerantinine alkaloids for future development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Natural products have made an enormous contribution in the treatment of cancer, with over half of the current anticancer drugs in clinical use being natural products or natural product derivatives1,2,3. Sometimes, however, there are disadvantages when using natural products as lead structures in drug discovery. Typically isolated from source in only minute quantities, the challenge of accessing useful quantities of these precious metabolites can present significant bottlenecks for development. This is particularly conspicuous when the natural supply has been exhausted and, in such instances, synthesis remains the only viable option. However, secondary metabolites are often incredibly challenging targets with unprecedented molecular connectivity and structural complexity4, and even when successful, total synthesis does not always result in adequate quantities of material for developmental studies5,6.

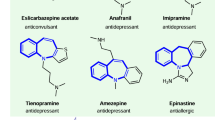

The tubulin binding7,8 Vinca indole alkaloids, including vincristine and vinblastine are classic examples of structurally complex natural products that are among the foremost drugs used in cancer chemotherapy1,2,3,9. However, owing to their structural complexity, the de novo synthesis of these important drugs remains a significant challenge10,11, and clinical supplies of vincristine and vinblastine primarily rely upon natural sources10,11,12,13,14,15. Another major limitation to the continued use of the Vinca alkaloids is the emergence of drug resistance, derived primarily from the overexpression of phosphoglycoprotein (Pgp) efflux pump, that is responsible for transporting many of the major drugs out of the cell16,17. Accordingly, the discovery and synthesis of bioactive alkaloids that overcome these resistance mechanisms is of high priority for anticancer drug development.

In 2008, several new Aspidosperma indole alkaloids, (−)-jerantinines A–G, were isolated by Kam and co-workers, from a leaf extract of the Malayan Tabernaemontana corymbosa Roxb. ex Wall18. The jerantinines displayed pronounced in vitro cytotoxicity toward drug-sensitive as well as vincristine-resistant (VJ300) KB cells (IC50 < 1 μg/mL)18, which is uncommon among simple Aspidosperma alkaloids. Studies have shown that both (−)-jerantinines A (1) and E (3) are microtubule-destabilising agents (MDAs)19,20, whereas 1 also induces tumour-specific cell death through modulation of splicing factor 3b subunit 1 (SF3B1)21.

The antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic activities of the jerantinines via mechanisms involving perturbation of validated antitumor targets warrant further investigation as potential chemotherapeutic agents. However, the inclusion of T. corymbosa on the endangered list of threatened species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)22, limits the source of these natural compounds, and a practical synthetic route is urgently required.

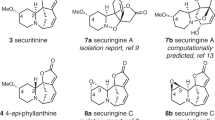

To date, there have been only three reported synthetic studies towards the jerantinine alkaloids. Waser et al. reported the first synthesis of jerantinine E (3), which involved a key homo-Nazarov cyclisation of an aminocyclopropane to access four of the five rings, leading to racemic (±)-(3) in 17-steps and 16% overall yield20. In 2017, Magauer and co-workers described a convergent synthesis to the ABC ring system of jerantinine E (3) that employed a β-C–H enone bromination followed by a palladium-catalysed amination and oxidative indole formation to yield a tricyclic core23.

Very recently, Jiang and co-workers completed the first total syntheses of (−)-jerantinines A (1), C (2) and E (3) in 12–13 steps24. The key steps of this route included a stereoselective intramolecular inverse-electron demand [4 + 2] cycloaddition, an α,β-unsaturated ketone indolisation and a Pd/C-catalysed cascade reaction.

Continuing our work on the biomimetic synthesis of natural products25,26,27, we report here the asymmetric and sustainable semi-syntheses of both (−)-jerantinine A (1) and (−)-jerantinine E (3), and provide supporting biological and structural data to further advocate a mechanism of action of the jerantinines via microtubule disruption.

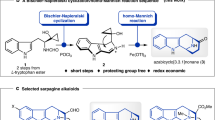

The indole alkaloid (−)-tabersonine (4) was proposed as a plausible precursor to the jerantinines — diverging from the vindoline biosynthetic pathway28,29, a selective C-1530 A-ring oxidation of 16-methoxytabersonine (5) would give 1 directly31,32. Alternatively, the C16 ortho-hydroxylation and subsequent methylation of the metabolite melodinine P (6) (from Melodinus suaveolens) would directly give 1 (Figs 1 and 2)33.

Thus, inspired by Nature’s efficiency in creating vast numbers of complex molecules from a single precursor, and the opportunity to exploit a readily available and sustainable natural feedstock, we elected to explore tabersonine (4) as a platform for synthetic elaboration into (−)-jerantinine A (1)34,35,36.

Studies commenced with the multi-gram scale extraction of 4 from the ground seeds of Voacanga Africana37,38, giving consistent yields of up to 1.4% by mass recovery. The reaction of 4 with N-iodosuccinimide in TFA at room temperature gave exclusively the 15-iodotabersonine (11) in 94% yield39. We anticipated that a Miyaura borylation followed by oxidation would conveniently install the required C-15 hydroxyl40,41,42, but upon experimentation we found that protection of the indoline nitrogen was first required to prevent unwanted side reactions. Gratifyingly, the N-Boc-iodotabersonine 12 reacted smoothly to give the boronate ester 13, which upon exposure to NMO yielded hydroxytabersonine 14 in 93% yield over 2 steps41. The next challenge was to install the critical C-16 hydroxyl, and we elected here to investigate a classical ortho-formylation followed by Dakin oxidation sequence; given the sterically more encumbered C-14 ring position, we were confident that this could be achieved with good regiochemical control. This proved to be robust and convenient; thus, upon treatment of the Boc-protected 14 with paraformaldehyde in the presence of MgCl2 and Et3N, the C-16-aldehyde 15 was isolated in 98% yield43. Exposing 15 to a solution of hydrogen peroxide with a trace amount of SeO244 in tert-butanol gave a complex mixture, and therefore an operationally convenient one-pot procedure was developed; aldehyde 15 was fully oxidised to the quinone, back-reduced with sodium dithionite and the catechol trapped by methylation to give the dimethoxy derivative 16 in 53% yield. Finally, sequential N-Boc deprotection and selective demethylation under Waser’s conditions20, furnished (−)-jerantinine A (1) in 72% yield, and 29% overall yield from (−)-tabersonine (4). Synthetic jerantinine A (1) was shown to be identical to natural jerantinine A through comparison of their 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data (Table S1). The conversion of 1 into (−)-jerantinine E (3) was accomplished upon selective reduction of the Δ6,7 double bond through H2 over PtO2 in 77% (23% overall yield, Scheme 1).

With significant amounts of synthetic 1 and synthetic intermediates en route to 1, we next explored the cytotoxicity of these molecules (See SI, Table S-2). The human-derived MCF-7 breast and HCT116 colorectal carcinoma cell lines were chosen, since they are representative of two of the most prevalent types of cancer. In vitro antitumour activity of synthetic 1 was indistinguishable from the natural compound; for example, in MTT tests GI50 values <1 μM against colorectal and mammary human-derived carcinoma cell lines were observed for both samples of 1 (Table 1) - dose-response profiles are shown in supplementary data (Fig. S-1). Furthermore, both the synthetic and natural 1 dramatically and significantly inhibited colony formation of HCT116 cells when treated at the GI50 concentration (Fig. 3A). Cell cycle analyses demonstrated that at 0.8 µM, both natural and synthetic 1 profoundly perturbed the cell cycle, causing stark arrest at G2/M phase (See SI, Fig. S-1). Collectively, these data advocate that mitotic microtubule assembly has been disrupted. Indeed, at 1 μM naturally sourced and synthetic (−)-1 both abolished tubulin polymerisation in vitro as profoundly as the 5 μM nocodazole control (Fig. 3B). MCF-7 cells were treated for 24 h with 0.8 µM 1, stained (DRAQ5 and monoclonal anti α-tubulin Ab) and the images viewed by confocal microscopy. As shown in Fig. 3C, many characteristic features of the action of a microtubule disrupting agent (MDA) were observed, including formation of multipolar spindles, misaligned chromosomes, multinucleation (aneuploidy) and nuclear fragmentation45,46.

(A) Effect of natural and synthetic 1 on HCT-116 colony formation at GI50 (see Table 1). Mean survival fraction (%) of treated cells as a percentage of the control population for HCT-116. Cells were seeded (400 per well) and allowed 24 h to attach before being challenged with jerantinine A (24 h). The number of colonies forming after 8 d incubation was determined. Mean (±S.E.M.) values are given. Data were generated from ≥3 separate trials; n = 2 per trial; (B) In vitro tubulin polymerisation in the presence of vehicle control, paclitaxel (5 μM; positive control), nocodazole (5 μM; negative control) or 1 (1 µM); (C) Immunofluorescent and DRAQ5 staining of x) untreated MCF-7 cells and y-z) cells exposed to synthetic 1 (1 × GI50 = 0.81 μM; 24 h), showing the effect on microtubules (green) and the cellular DNA (purple). Synthetic (−)-jerantinine A (1) caused multinucleation (i), nuclear fragmentation (ii) and formation of multipolar spindles (iii).

Following these results, we tested the impact of jerantinine A (1) and colchicine on breast cancer cell growth in 3D culture (Fig. 4). After 96 h of exposure to either agent, the cell density of both cell lines (measured as area) was decreased compared to control (Fig. 4B and C). Jerantinine A (1) decreased cell density of the MDA-MB-231 to a greater extent than colchicine following 96 h of exposure (Fig. 4B). The invasive nature of the MDA-MB-231 triple negative breast cancer cell line was also decreased by treatment with jerantinine A (1) or colchicine.

(A) MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 breast cancer cells grown in 3D culture with vehicle (DMSO), jerantinine A (1) (5.36 µM or 1.22 µM‚ respectively) or colchicine (10 µM or 14.5 µM‚ respectively). Images from 96 h post agent exposure. Scale bar represents 200 µm. (B) Quantification of the area of the MDA-MB-231 3D colonies over a 96 h period post agent addition. Mean (±S.E.M.) values are given. (C) Quantification of the area of the MCF-7 3D colonies over a 96 h period post agent addition. Mean (±S.E.M.) values are given. Data were generated from ≥2 separate trials; n = 2 per trial; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

Soaking experiments with a selection of the jerantinine metabolites and derivatives into a crystal formed by a protein complex composed of two αβ-tubulin heterodimers, the stathmin-like protein RB3 and tubulin tyrosine ligase (T2R-TTL)47,48, yielded the tubulin-jerantinine B acetate (9) structure at 2.4 Å resolution (Fig. 5A; Table S-3). The overall structure of the two tubulin dimers in the T2R-TTL-9 complex superimposed well with the one obtained in the absence of a ligand49 (Fig. S-3A; rmsdoverall of 0.48 Å over 1814 Cα-atoms; rmsdchain B 0.24 Å over 351 Cα-atoms). This result suggests that binding of the ligand does not affect the gross conformation of tubulin. Thus, the complex structure reveals that 9 binds to the colchicine site of tubulin that is shaped by residues of strands βS8 and βS9, loop βT7, and helices βH7 and βH8 of β-tubulin, and loop αT5 of α-tubulin (Fig. 5B).

Crystal structure of the tubulin-jerantinine B acetate (9) complex. (A) Overall view of the T2R-TTL-jerantinine B acetate complex structure. The α- and β-tubulin chains are in dark and light grey ribbon representation, respectively. The tubulin-bound 9 and GTP molecules are represented as green and orange spheres, respectively; (B) Close-up view of the interactions observed between 9 (green) and tubulin (grey). Interacting residues of tubulin are shown in stick representation and are labelled. Oxygen and nitrogen atoms are coloured red and blue, respectively; carbon atoms are in green 9 or grey (tubulin). Secondary structural elements of tubulin are labelled in blue. For simplicity, only α-tubulin residues are indicated with an α; (C) Superimposition of the tubulin-9 (green/grey) and the tubulin-colchicine (pink; PDB ID 4O2B; rmsd of 0.204 Å over 351 Cα-atoms) complex structures. The structures were superimposed onto their β1-tubulin chains; (D) Molecular docking of (−)-jerantinine A (1) in the colchicine binding pocket of tubulin; this pocket is formed by residues in the αT5-loop on α-tubulin, and βH7, βH8, βS8, βS9 and the βT7-loop on β-tubulin. For additional experimental details see the Supporting Information.

Superimposition of the tubulin-9 structure onto the tubulin-colchicine structure (rmsd of 0.204 Å over 351 Cα-atoms, chain B)49 revealed a perfect overlap of the jerantinine A-ring of 9 with the C-ring of colchicine and two major conformational changes in the binding site of 9 (Fig. 5C). In the jerantinine structure, Thr179 on the αT5 loop is in the flipped-in conformation and forms a hydrophobic contact to Leu248 on the βT7 loop. In the colchicine structure Thr179 is in the flipped-out conformation to avoid clashes with the acetamide moiety. Moreover, jerantinine-binding induces a rearrangement of Leu248 on the βT7 loop to prevent clashes with the epoxide moiety on the D-ring of 9 (Fig. 4C), and of Ala250 and Leu255 to fill the space that is otherwise occupied by the A-ring of colchicine.

Tubulin dimers in microtubules assume a “straight” structure; in contrast, free tubulin is characterised by a “curved” conformation50,51. The jerantinine B acetate (9) prevents the curved-to-straight structural transition by sterically hindering the βT7 loop adopting its conformation characteristic of the straight tubulin state (Fig. S-3B), a mechanism that is similar to other colchicine-site ligands49,51,52,53.

Subsequent molecular docking studies revealed a distinct preference of jerantinines A (1) and E (3) for the colchicine pocket (Fig. 5D, Table S-4)54. Binding energies to either the vinblastine or taxol sites were approximately 10 and 15 kJ mol−1, respectively, lower than the colchicine site. Jerantinine B acetate (9) was calculated as the tightest binding ligand of the family, and was predicted to bind ~5 kJ mol−1 more tightly than colchicine. The structure of jerantinine B acetate closely matches the experimentally determined structure – rmsd of 0.68 Å. The predicted binding orientation of all the jerantinine derivatives, in the colchicine binding site, mirror that of jerantinine B acetate (9).

In conclusion, we have described the asymmetric synthesis of the Aspidosperma alkaloid (−)-jerantinine A (1) in 9 steps and 29% overall yield, using a sustainable semi-synthetic approach. The selective reduction of (−)-1 enabled the asymmetric synthesis of the corresponding (−)-jerantinine E (3). Our biomimetic approach began from the natural building block and plausible biosynthetic precursor (−)-tabersonine (4), that is readily available in large quantities from a sustainable plant-based source (Voacanga Africana). The synthesis enabled us to investigate the biological profile of (−)-jerantinine A (1), showing that activity of synthetic 1 is indistinguishable from that of the natural material against human derived breast (MCF-7) and colon carcinoma (HCT116) cell lines. A 3D culture assay showed that jerantinine A (1) decreased the cell density of two breast cancer cell lines, in particular demonstrating greater effectiveness than colchicine against MDA-MB-231 cells. Investigations into the mode of action suggested that 1 acts via disruption of the microtubule network, as indicated by its potent inhibitory activity displayed in tubulin polymerisation in vitro. This particular mode of action was further corroborated by solving of the crystal structure of the tubulin—jerantinine B acetate complex, revealing binding to the colchicine site and prevention of the “curved-to-straight” tubulin conformational transition that is necessary to enable microtubule formation.

References

Cragg, G., Kingston, D. & Newman, D. Anticancer agents from natural products, second ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton (2011).

Basmadjian, C. et al. Cancer wars: natural products strike back. Front. Chem. 2, 1–18 (2014).

Cragg, G. M. & Newman, D. J. Natural Products: a Continuing Source of Novel. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1830, 3670–3695 (2013).

Sierra, M., de la Torre, M. & Cossio, F. More Dead Ends and Detours: En Route to Successful Total Synthesis. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim (2013).

Yuan, C., Jin, Y., Wilde, N. C. & Baran, P. S. Short, Enantioselective Total Synthesis of Highly Oxidized Taxanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 8280–8284 (2016).

Mendoza, A., Ishihara, Y. & Baran, P. S. Scalable enantioselective total synthesis of taxanes. Nat. Chem. 4, 21–25 (2012).

A number of natural products and natural product derivatives are known to bind to tubulin; for a recent review on the topic see: Dong, M., Liu, F., Zhou, H., Zhai, S. & Yan, B. Novel Natural Product- and Privileged Scaffold-Based Tubulin Inhibitors Targeting the Colchicine Binding Site, M olecules, 21, 1375 (2016).

Yue, Q.-Y., Liu, X. & Guo, D.-A. Microtubule-Binding Natural Products for Cancer Therapy. Planta Med. 76, 1037–1043 (2010).

Gigant, B. et al. Structural basis for the regulation of tubulin by vinblastine. Nature 435, 519–522 (2005).

Sears, J. E. & Boger, D. L. Total Synthesis of Vinblastine, Related Natural Products, and Key Analogues and Development of Inspired Methodology Suitable for the Systematic Study of Their Structure-Function Properties. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 653–662 (2015).

Ishikawa, H. et al. Total Synthesis of Vinblastine, Vincristine, Related Natural Products, and Key Structural Analogues. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 4904–4916 (2009).

Potier, P., Langlois, N., Langlois, Y. & Guéritte, F. Partial Synthesis of Vinblastine-type Alkaloids. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 670–671 (1975).

Langlois, N., Guéritte, F., Langlois, Y. & Potier, P. Application of a Modification of the Polonovski Reaction to the Synthesis of Vinblastine-Type Alkaloids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 98, 7017–7024 (1976).

Kutney, J. P., Ratcliffe, A. H., Treasurywala, A. M. & Wunderly, S. Studies on the synthesis of bisindole alkaloids II. The synthesis of 3′,4′-dehydrovinblastine, 4′-deoxovinblastine and related analogues. The biogenetic approach. Heterocycles 3, 639–649 (1975).

Kutney, J. P., Hibino, T., Jahngen, E. & Okutani, T. Total Synthesis of Indole and Dihydroindole Alkaloids. Helv. Chim. Acta. 59, 2858–2882 (1976).

Dumontet, C. & Sikic, B. I. Mechanisms of action of and resistance to antitubulin agents: Microtubule dynamics, drug transport, and cell death. J. Clin. Oncol. 17, 1061–1070 (1999).

Haber, M. et al. Altered expression of M beta 2, the class II beta-tubulin isotype, in a murine J774.2 cell line with a high level of taxol resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 31269–31275 (1995).

Lim, K.-H., Hiraku, O., Komiyama, K. & Kam, T.-S. Jerantinines A-G, cytotoxic Aspidosperma alkaloids from Tabernaemontana corymbosa. J. Nat. Prod. 71, 1591–1594 (2008).

Raja, V. J., Lim, K. H., Leong, C. O., Kam, T. S. & Bradshaw, T. D. Novel antitumour indole alkaloid, Jerantinine A, evokes potent G2/M cell cycle arrest targeting microtubules. Invest. New Drugs. 32, 838–850 (2014).

Frei, R. et al. Total Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Jerantinine E. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 13373–13376 (2013).

Chung, F. F. -L. et al. Jerantinine A induces tumor-specific cell death through modulation of splicing factor 3b subunit 1 (SF3B1). Sci. Rep. 7, 1–13 (2017).

Iucnredlist.org. T abernaemontana corymbosa, http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/34504/0 (2017).

Huber, T., Preuhs, T. A., Gerlinger, C. K. G. & Magauer, T. Development of a β-C-H Bromination Approach toward the Synthesis of Jerantinine E. J. Org. Chem. 52, 7410–7419 (2017).

Wang, N., Liu, J., Wang, C., Bai, L. & Jiang, X. Asymmetric Total Syntheses of (−)-Jerantinines A, C, and E, (−)−16-Methoxytabersonine, (−)-Vindoline, and (+)-Vinblastine. Org. Lett. 20, 292–295 (2018).

Moore, J. C., Davies, E. S., Walsh, D. A., Sharma, P. & Moses, J. E. Formal synthesis of kingianin A based upon a novel electrochemically-induced radical cation Diels–Alder reaction. Chem. Commun. 50, 12523–12525 (2014).

Sharma, P., Ritson, D. J., Burnley, J. & Moses, J. E. A synthetic approach to kingianin A based on biosynthetic speculation. Chem. Commun. 47, 10605 (2011).

Sharma, P. et al. Biomimetic Synthesis and Structural Reassignment of the Tridachiahydropyrones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 5966–5972 (2009).

DeLuca, V. et al. Biosynthesis of Indole Alkaloids: Developmental Regulation of the Biosynthetic Pathway from Tabersonine to Vindoline in Catharanthus roseus. J. Plant Physiol. 125, 147–156 (1986).

Qu, Y. et al. Completion of the seven-step pathway from tabersonine to the anticancer drug precursor vindoline and its assembly in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 6224–6229 (2015).

Lim et al. [ref 18] uses the biogentic numbering system. The numbering system used throughout this paper is one proposed by: Le Men, J. & Taylor, W. I. A uniform numbering system for indole alkaloids. Experientia. 21, 508–510 (1965).

Besseau, S. et al. A Pair of Tabersonine 16-Hydroxylases Initiates the Synthesis of Vindoline in an Organ-Dependent Manner in Catharanthus roseus. Plant Physiol. 163, 1792–1803 (2013).

Murata, J. & Luca, V. De. Localization of tabersonine 16-hydroxylase and 16-OH tabersonine-16-O- methyltransferase to leaf epidermal cells defines them as a major site of precursor biosynthesis in the vindoline pathway in Catharanthus roseus. Plant J. 44, 581–594 (2005).

Liu, Y.-P. et al. Melodinines M-U, cytotoxic alkaloids from Melodinus suaveolens. J. Nat. Prod. 75, 220–224 (2012).

Ziegler, F. E. & Bennett, G. B. Total synthesis of (+−)-tabersonine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 93, 5930–5931 (1971).

Kozmin, S. A., Iwama, T., Huang, Y. & Rawal, V. H. An efficient approach to Aspidosperma alkaloids via [4 + 2] cycloadditions of aminosiloxydienes: Stereocontrolled total synthesis of (±)-tabersonine. Gram-scale catalytic asymmetric syntheses of (+)-tabersonine and (+)-16-methoxytabersonine. Asymmetric Syntheses of (+)-Aspidospermidine and (−)-Quebrachamine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 4628–4641 (2002).

Kim, J.-Y., Suhl, C.-H., Lee, J.-H. & Cho, C.-G. Directed Fischer Indolization as an Approach to the Total Syntheses of (+)-Aspidospermidine and (−)-Tabersonine. Org. Lett. 19, 6168–6171 (2017).

Gagne, R. A. The Isolation of Tabersonine and the Synthesis of Vincamine, https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/handle/10625/6075 (1991).

Levy, J. US Patent US3892755 A (1975).

Chen, F., Lei, M. & Hu, L. Synthesis of C-10 tabersonine analogues by palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. Synth. 46, 3199–3206 (2014).

Zhang, N. et al. Structure–Activity Relationship (SAR) Optimization of 6-(Indol-2-yl)pyridine-3-sulfonamides: Identification of Potent, Selective, and Orally Bioavailable Small Molecules Targeting Hepatitis C (HCV) NS4B. J. Med. Chem. 57, 2121–2135 (2014).

Zhu, C., Wang, R. & Falck, J. R. Mild and rapid hydroxylation of aryl/heteroaryl boronic acids and boronate esters with N-oxides. Org. Lett. 14, 3494–3497 (2012).

Gotoh, H., Duncan, K. K., Robertson, W. M. & Boger, D. L. 10′-fluorovinblastine and 10′-fluorovincristine: Synthesis of a key series of modified vinca alkaloids. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2, 948–952 (2011).

Hofsløkken, N. U. et al. Convenient Method for the ortho-Formylation of Phenols. Acta Chemica Scandinavica. 53, 258–262 (1999).

Guzmán., J. A. et al. Baeyer-Villiger Oxidation of β-Aryl Substituted Unsaturated Carbonyl Compounds with Hydrogen Peroxide and Catalytic Selenium Dioxide. Synth. Commun. 25, 2121–2133 (1995).

Hengartner, M. O. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature 407, 770–776 (2000).

González-Cid, M., Cuello, M. T. & Larripa, I. Comparison of the aneugenic effect of vinorelbine and vincristine in cultured human lymphocytes. Mutagenesis 14, 63–66 (1999).

Prota, A. E. et al. Structural basis of tubulin tyrosination by tubulin tyrosine ligase. J. Cell Biol. 200, 259–270 (2013).

Prota, A. E. et al. Molecular Mechanism of Action of Microtubule-Stabilizing Anticancer Agents. Science 339, 587–590 (2013).

Brouhard, G. J. & Rice, L. M. The contribution of αβ-tubulin curvature to microtubule dynamic. J. Cell Biol. 207, 323–334 (2014).

Prota, A. E. et al. The novel microtubule-destabilizing drug BAL27862 binds to the colchicine site of tubulin with distinct effects on microtubule organization. J. Mol. Biol. 426, 1848–1860 (2014).

Ravelli, R. B. G. et al. Insight into tubulin regulation from a complex with colchicine and a stathmin-like domain. Nature 428, 198 (2004).

Dorleans, A. et al. Variations in the colchicine-binding domain provide insight into the structural switch of tubulin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 13775–13779 (2009).

Gaspari, R., Prota, A. E., Bargsten, K., Cavalli, A. & Steinmetz, M. O. Structural basis of cis- and trans-combretastatin binding to tubulin. Chem. 2, 102–113 (2017).

Lu, Y., Chen, J., Xiao, M., Li, W. & Miller, D. D. An overview of tubulin inhibitors that interact with the colchicine binding site. Pharm. Res. 29, 2943–2971 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank La Trobe University (C.J.S.) and the University of Nottingham (P.A.S. and H.E.) for providing PhD scholarships. We are indebted to Takashi Tomizaki and Meitian Wang for excellent technical assistance with the collection of X-ray data at beamline X06SA of the Swiss Light Source (Paul Scherrer Institut, Villigen PSI, Switzerland). J.E.M. thanks the ARC for a Future Fellowship (FT170100156). B.S.P. thanks the NHMRC for funding (BSP 1127754). M.E.Q. thanks the Higher Committee for Education Development in Iraq (HCED) for sponsorship. This work was further supported by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (31003A_166608; to M.O.S.). Coordinates of the X-ray crystal structures have been deposited in the RCSB PDB (www.rcsb.org) under accession number 6GF3 (tubulin-9).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.E.M., M.O.S., T.D.B., B.J.S. and B.S.P. designed the research. C.J.S., P.A.S., H.E. and A.S.B. developed and performed the synthetic route. M.E.Q. performed the biological assays, H.C. conducted the confocal experiments, H.M.D. performed the 3D culture assays. A.E.P. and N.O. generated the X-ray crystal structure. K.-H.L. and T.-S.K. provided natural samples for biological testing and B.J.S. performed the computational modelling. J.E.M. prepared the manuscript with the assistance of the co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Smedley, C.J., Stanley, P.A., Qazzaz, M.E. et al. Sustainable Syntheses of (−)-Jerantinines A & E and Structural Characterisation of the Jerantinine-Tubulin Complex at the Colchicine Binding Site. Sci Rep 8, 10617 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28880-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28880-2

This article is cited by

-

The natural alkaloid Jerantinine B has activity in acute myeloid leukemia cells through a mechanism involving c-Jun

BMC Cancer (2020)

-

Targeting mRNA processing as an anticancer strategy

Nature Reviews Drug Discovery (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.