Abstract

Recent history has provided us with one pandemic (Influenza A/H1N1) and two severe viral outbreaks (Ebola and Zika). In all three cases, post-hoc analyses have given us deep insights into what triggered these outbreaks, their timing, evolutionary dynamics, and phylogeography, but the genomic characteristics of outbreak viruses are still unclear. To address this outstanding question, we searched for a common denominator between these recent outbreaks, positing that the genome of outbreak viruses is in an unstable evolutionary state, while that of non-outbreak viruses is stabilized by a network of correlated substitutions. Here, we show that during regular epidemics, viral genomes are indeed stabilized by a dense network of weakly correlated sites, and that these networks disappear during pandemics and outbreaks when rates of evolution increase transiently. Post-pandemic, these evolutionary networks are progressively re-established. We finally show that destabilization is not caused by substitutions targeting epitopes, but more likely by changes in the environment sensu lato. Our results prompt for a new interpretation of pandemics as being associated with evolutionary destabilized viruses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past few years, humanity has been affected by three major zoonotic events, with an Influenza pandemic in 20091, an Ebola virus outbreak in 2014–162, and a Zika outbreak in 2015–163. In all these examples, the epidemiological and evolutionary dynamics of the pathogens involved, i.e., their phylodynamics4, were meticulously reconstructed. For instance, in the case of Ebola, an initial phylogenetic study showed evidence that the outbreak originated from a single zoonotic event in an unknown animal reservoir2, and that the resulting epidemic then spread to the largest and closest neighboring cities following the gravity model5,6, with some exceptions7. However, in this general context of severe outbreaks, we still do not quite fully understand what characterizes the evolutionary dynamics of the viruses during such events.

Recently, in an attempt to understand the genomic determinants of antigenic properties and drug resistance in influenza viruses, we described a novel algorithm to uncover pair of amino acids in a protein that evolve in a correlated manner8. We found that influenza A viruses show extensive evidence for correlated evolution, to such an extent that some amino acids evolve correlatively with more than one other site, hereby forming dense (undirected) networks (see also9). We furthermore uncovered that some of these pairs of sites are known to be epistatically interacting – specifically, experimental studies show that a mutation at one of these sites lowers viral fitness, which is then restored by a compensatory mutation10. Moreover, we showed that similar networks of sites can be found in the Ebola virus, with some of these sites also involved in episodes of adaptive evolution11. In light of these results, we here hypothesized that during an outbreak or a pandemic, these networks of tightly correlated sites might be transiently disrupted, hereby leading to a virus that is, from an evolutionary point of view, destabilized.

Such a network destabilization would require that some of the intrinsic properties describing these networks change in a similar manner across different viruses. One way of studying these properties is by resorting to the theory used in social networks analysis, and more generally developed in graph theory12. In our case, a network is made of nodes, that are amino acid sites in viral proteins, and a link between two amino acids means that these two sites show statistical evidence for evolving in a correlated manner. Both the structure of this network, and the pattern of connections among its nodes, influence its behavior: for instance, scale-free networks, where node connectivity follows a power law, are extremely robust to disruptions13, just like dense networks14, while the most connected nodes are also the most important ones in protein-protein interaction networks15. Such properties can be derived by summarizing a network with different statistics, such as the number of connections that a particular node has (its degree), or the shortest distance between each pair of nodes (the average path length).

In order to contrast the evolutionary dynamics of pandemic versus non-pandemic viruses, we here used these statistics to assess the stability of these networks of amino acids that evolve in a correlated manner. We predicted that viral evolutionary dynamics are weakened during a pandemic. As these dynamics often lead to complex networks of interactions9,11, we more specifically tested how the structure of these correlation networks is affected during an outbreak. We show that during a pandemic, the evolutionary dynamics of viral genes are severely disrupted, but also that they are progressively restored after the pandemic.

Results

Networks of correlated sites are destabilized during outbreaks

In search for evolutionary differences between regular epidemics and severe outbreaks, we first contrasted the glycoprotein precursor (GP) sequences of the Ebola virus that circulated before and during the 2014/2016 outbreak. For this, we identified with a Bayesian graphical model16 the pairs of nucleotides that show evidence for correlated evolution in each data set, before and during the outbreak. As in previous work9,11, we found that these pairs of sites form a network. A first inspection of these networks of correlated sites revealed a striking difference between pre-2014 and outbreak sequences: in particular at weak correlations, the pre-2014 interaction networks are very dense and involve most sites of GP, while only a small number of sites are interacting in outbreak viruses (Fig. 1). Furthermore, at increasing correlation strengths, outbreak networks become completely disconnected faster: at posterior probability Pr = 0.80 some sites still interact in pre-2014 proteins, while all interactions have disappeared from Pr = 0.60 in outbreak proteins (Fig. 1). Similar patterns for the Influenza (at two antigenes, the hemagglutinin [HA] and the neuraminidase [NA]; Figures S3–S4) and Zika viruses (polymerase NS5; Fig. S5) suggest that during a severe outbreak, an evolutionary destabilization of viral genes occurs, especially among sites that entertain weak interactions.

Correlation network of pre-outbreak and outbreak Ebola viruses. Networks of correlated sites in the GP protein are shown in each panel. The top row shows networks for the viruses circulating before the 2014 outbreak (blue); the bottom row shows networks for outbreak viruses (red). Each column shows networks for different strengths of correlation, from weak (Pr = 0.05) to strong (Pr = 0.95). Nodes represent animo acid sites, and edges correlations. Node sizes are proportional to diameter.

Destabilization affects weakly correlated sites

To further investigate this destabilization hypothesis, we analyzed the structure of these networks with the tools of social network analysis and graph theory12. Again, we found a consistent pattern when contrasting regular and outbreak viruses: at weak to moderate interactions (Pr ≤ 0.50), outbreak viruses have networks of smaller diameter, shorter path length, and reduced eccentricity (Fig. 2a–c, columns 1–5). All these patterns point to fewer connected sites in outbreak viruses. Betweenness is smaller for outbreak viruses (except Ebola), and transitivity tends to be larger (except Zika). These last two measures also suggest that interactions among sites are weakened in outbreak viruses. Other networks statistics failed to show a clear pattern (Fig. S6): in particular, there were no clear differences in terms of degree, centrality or homophily – all properties that are not directly related to network stability.

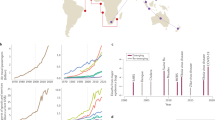

Network properties between pandemic and non-pandemic viruses. Results are shown for Ebola (column 1), Zika (2) and Influenza viruses: for HA and NA circulating in 2009 in (3) and (4), respectively, and for pandemic viruses circulating between the 2009–10 (deep red) and the 2015–16 (deep blue) season in (5) and (6). Pandemic viruses are show in red, while non-pandemic ones are in blue. Shading: 95% confidence envelopes of the LOESS regressions. Five network measures are shown: (a) diameter, (b) average path length, (c) eccentricity, (d) betweenness, and (e) transitivity.

Post-outbreak re-stabilization

Should these weak interactions play a critical role in the stabilization of viruses outside of pandemics, we would expect to observe the strengthening of all network statistics as years go by after the pandemic. To test this prediction and estimate how long this re-stabilization process can take, we analyzed in a similar way all influenza seasons in the Northern hemisphere following the 2009 pandemic (until 2015–16). Consistent with our prediction, both HA and NA genes show a gradual transition between a typical pandemic state to a regular state in two-to-three seasons (Fig. 2, column 5–6, respectively).

Non-genetic sources of destabilization

To understand what the potential sources of this destabilization are, we assessed the involvement of viral antigenic determinants/epitopes. Should mutations accumulating in such epitopes be responsible for destabilization, we would expect (i) that weak interactions in non-pandemic viruses involve mostly epitopes, and (ii) that pandemics be associated with the disappearance of these interactions at epitopes first. Figure 3 shows no evidence supporting this hypothesis (X 2 = 0.0663, df = 1, P = 0.7967): non-pandemic viruses show a small number of predicted epitopes in their interaction network, that do not act as central hubs of these networks, while pandemic viruses may actually show an enrichment in interacting epitopes. This suggests that non-genetic factors are likely responsible for the initial destabilization of the genome of pandemic viruses. Changes in their ecology/environment (vector) cannot be ruled out.

Discussion

To understand how evolutionary dynamics are affected during a viral outbreak, we compared non-outbreak and outbreak viruses. Based on the hypothesis that non-outbreak viruses are in a stable evolutionary equilibrium, and that such a stability is mediated by correlated evolution among pairs of sites in viral genes, we reconstructed the coevolution patterns in genes of non-outbreak and outbreak viruses. In line with our prediction, we found that outbreak viruses exhibit fewer coevolving sites than their non-outbreak counterparts, and that these interactions are gradually restored after the outbreak, at least in the case of the Influenza (2009 H1N1) virus for both HA and NA.

Two independent lines of evidence are consistent with our destabilization hypothesis. First, all three viruses showed temporary increases in their rate of molecular evolution during each outbreak1,2,3; such increases can be expected to disrupt the coevolutionary structure, and hence, destabilize viral genomes. We showed that epitopes were not particular targets of this mutational process. This can be expected, as mutations (i) most likely affect sites randomly, and (ii) are quickly lost from the viral population. Second, a probable cause of the epidemics can be identified in all cases studied here. For Influenza, the 2009 pandemic was caused by a series of reassortment events that affected the two genes studied here, HA (triple-reassortant swine) and NA (Eurasian avian-like swine)1. Such exchanges of segments can very well destabilize the evolutionary dynamics, at least of the implicated segments. Similarly, a zoonotic event was implicated in the Ebola outbreak2, and a change of continent in the case of Zika3,17,18. These corresponding changes of environment (sensu lato) might have triggered the destabilizations observed here. In addition to such environmental changes, it is very likely that destabilization reflects a complex interaction between the genetics of viruses, their demographic fluctuations and environmental changes.

This argument is further supported by recent work in physics, where it was shown that dense networks are more resilient, i.e. resistant to small perturbations, than sparser ones14. Moreover, in their simplest example, these authors modeled abundances in a community of mutualistic species, where the mutualistic term describes the pairs of interacting species; perturbations were then applied to the system to assess resilience. They showed that small perturbations did not affect average abundances, which remained high – their ‘desirable’ state. However, above a particular perturbation threshold, a bifurcation occured and a new ‘undesirable’ state, at low abundances, was reached. Our results are consistent with a similar system behavior, where the network of correlated amino acids is resilient to perturbations up to a certain point, when a bifurcation to an ‘undesirable’ state (associated with the pandemic) occurs, and the system returns to its resilient state post-pandemic. One major difference though is that we observed a progressive return to stability in the case of influenza, while the resilience model suggests a second bifurcation, i.e. an instantaneous change, to the ‘desirable’ state14.

One outstanding question is about the importance of weak patterns of coevolution within a gene: how can it be explained that it is essentially weak correlations (around Pr = 0.25) that distinguish non-outbreak from outbreak viruses? In a recent study on mice, four phenotypes were quantitatively analyzed following large intercrosses, and linear regressions on pairs of quantitative trait loci were used to detect non-additive effects, i.e., epistasis; it was then shown that most epistatic interactions were weak and, critically, tended to stabilize phenotypes towards the mean of the population19. Viruses are not mice, and not all the correlations that we detected are involved in epistatic interactions, but both this work in mice and the evidence presented here go in the same direction: weak interactions have a stabilizing effect on viral genes and their phenotype (regular epidemics). It is further possible that the intricate nature of these weak correlation networks has higher-order effects19, that in turn increase canalization and hence may help viruses weather modest environmental and genotypic fluctuations20. The elimination of these many weak interactions has a destabilizing effect that may be caused by or lead to outbreaks. Our findings call for a new interpretation of pandemics that, from an evolutionary point of view, appeared to be associated with unhealthy or diseased viruses. While the evidence shown here does not support the causal nature of this relationship, monitoring correlation networks could help forecast imminent outbreaks.

Methods

Sequence retrieval

Nucleotide sequences were retrieved for three viruses: Influenza A, Ebola, and Zika, for select protein-coding genes, chosen because they represent the most sequenced / studied genes for each of these viruses11,21,22,23. All sequences were downloaded in May 2016 (Table S1).

Full-length Influenza A sequences were retrieved directly from the Influenza Virus Resource24. Only H1N1 sequences circulating in humans for the hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) genes were downloaded. These two genes are also very commonly studied and largely sampled in public databases22,23. Two types of data sets were constructed: one containing pandemic and non-pandemic sequences circulating in 2009, the pandemic year, and one containing pandemic sequences circulating from August 1 to July 31 of each season in the Northern temperate region between 2009/2010 and 2015/2016 (seven seasons in total). Only unique sequences were retrieved.

For Ebola, the virion spike glycoprotein precursor, GP, was retrieved because of its key role in the emergence of the 2014 outbreak showing evidence for both correlated and adaptive evolution11 as follows. A GP sequence (KX121421) was drawn at random from the 2014 strain used previously11 and was employed as a query for a BLASTn search25 at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. A conservative E-value threshold of 0 (E < 10−500) was used, which led to 1,181 accession numbers. As most of these accession numbers correspond to full genomes, while only GP is of interest, we (i) retrieved all corresponding GenBank files, (ii) extracted coding sequences with ReadSeq26 of all genes, (iii) concatenated the corresponding FASTA files into a single file, (iv) which was then used to format a sequence database for local BLASTn searches, and (v) used GP from KX121421 in a second round of BLASTn searches (E < 10−250, coverage >75%).

In the case of Zika, sequences of 252 complete genomes were retrieved from the Virus Pathogen Resource (www.viprbrc.org). The RNA-dependent RNA polymerase NS5 was specifically extracted by performing local BLASTn searches as described above. It is one of the most studied Zika genes21,27, as it is essential for the replication of the virus27.

Phylogenetic analyses

Sequences were all aligned with Muscle28 with the fastest options (-maxiters 1 -diags). Alignments were visually inspected with AliView29 to remove rogue sequences and sequencing errors. Phylogenetic trees were inferred by maximum likelihood under the General Time-Reversible model with among-site rate variation30 with FastTree31. As outbreak sequences (Ebola and Zika viruses) cluster away from non-pandemic sequences, we used the subtreeplot() function in APE32 to retrieve accession numbers of pandemic sequences and hence separate them from non-pandemic sequences with minimal manual input. FastTree was used a second time to estimate phylogenetic trees of the subset alignments, with the same settings as above.

Network analyses of correlated sites

Amino acid positions (“sites”) that evolve in a correlated manner were identified with the Bayesian graphical model (BGM) in SpiderMonkey16 as implemented in HyPhy33. Briefly, ancestral mutational paths were first reconstructed under the MG94 × HKY85 substitution model34 along each branch of the tree estimated above at non-synonymous sites. These reconstructions were recoded as a binary matrix in which each row corresponds to a branch and each column to a site of the alignment. A BGM was then employed to identify which pairs of sites exhibit correlated patterns of substitutions. Each node of the BGM represents a site and the presence of an edge indicates the conditional dependence between two sites. Such dependence was estimated locally by a posterior probability. Based on the chain rule for Bayesian networks, such local posterior distributions were finally used to estimate the full joint posterior distribution35. A maximum of two parents per node was assumed to limit the complexity of the BGM. Posterior distributions were estimated with a Markov chain Monte Carlo sampler that was run for 105 steps, with a burn-in period of 10,000 steps sampling every 1,000 steps for inference. Analyses were run in duplicate to test for convergence (Figures S1–S2).

The estimated BGM can be seen as a weighted network of coevolution among sites, where each posterior probability measures the strength of coevolution. Each probability threshold gives rise to a network whose topology can be analyzed based on a number of measures12 borrowed from social network analysis and graph theory. We focused in particular on six statistics: average diameter, the length of the longest path between pairs of nodes; average betweenness, measures the importance of each node in their ability to connect to dense subnetworks; assortative degree, measures the extent to which nodes of similar degree are connected to each other (homophily); eccentricity, is the shortest path linking the most distant nodes in the network; average strength, rather than just count the number of connections of each node (degree), strength sums up the weights of all the adjacent nodes; average path length, measures the shortest distance between each pair of nodes. All measures were computed using the igraph R package ver. 1.0.136. Thresholds of posterior probabilities for correlated evolution ranged from 0.01 (weak) to 0.99 (strong). LOESS regressions were then fitted to the results.

Epitope analyses

Epitopes were predicted using the NetCTL 1.2 Server37. Briefly, Cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) epitopes are predicted based on a neural network algorithm trained on a database of human MHC class I ligands. Epitopes can be predicted for 12 MHC supertypes (A1, A2, A3, A24, A26, B7, B8, B27, B39, B44, B58, B62), that are broad families of very similar peptides for which independent neural network models have been generated. As such, we ran the epitope prediction for each supertype independently, on non-outbreak and outbreak viruses. Circos plots were generated with the circlize R package ver. 0.3.1038. Scripts and sequence alignments used are available from github.com/sarisbro.

References

Smith, G. J. D. et al. Origins and evolutionary genomics of the 2009 swine-origin H1N1 influenza A epidemic. Nature 459, 1122–5 (2009).

Gire, S. K. et al. Genomic surveillance elucidates Ebola virus origin and transmission during the outbreak. Science 345, 1369–72 (2014).

Faria, N. R. et al. Zika virus in the Americas: Early epidemiological and genetic findings. Science 352, 345–9 (2016).

Grenfell, B. T. et al. Unifying the epidemiological and evolutionary dynamics of pathogens. Science 303, 327–32 (2004).

Zipf, G. K. The P1 P2/D hypothesis: on the intercity movement of persons. American sociological review 11, 677–686 (1946).

Xia, Y., Bjørnstad, O. N. & Grenfell, B. T. Measles metapopulation dynamics: a gravity model for epidemiological coupling and dynamics. Am Nat 164, 267–81 (2004).

Dudas, G. et al. Virus genomes reveal factors that spread and sustained the Ebola epidemic. Nature 544, 309–315 (2017).

Nshogozabahizi, J. C., Dench, J. & Aris-Brosou, S. Widespread historical contingency in influenza viruses. Genetics 205, 409–420 (2017).

Poon, A. F. Y., Lewis, F. I., Pond, S. L. K. & Frost, S. D. W. An evolutionary-network model reveals stratified interactions in the V3 loop of the HIV-1 envelope. PLoS Comput Biol 3, e231 (2007).

Gong, L. I., Suchard, M. A. & Bloom, J. D. Stability-mediated epistasis constrains the evolution of an influenza protein. Elife 2, e00631 (2013).

Ibeh, N., Nshogozabahizi, J. C. & Aris-Brosou, S. Both epistasis and diversifying selection drive the structural evolution of the Ebola virus glycoprotein mucin-like domain. J Virol 90, 5475–84 (2016).

Newman, M. Networks: an introduction (OUP Oxford, 2010).

Albert, Jeong & Barabasi. Error and attack tolerance of complex networks.. Nature 406, 378–82 (2000).

Gao, J., Barzel, B. & Barabási, A.-L. Universal resilience patterns in complex networks. Nature 530, 307–12 (2016).

Jeong, H., Mason, S. P., Barabási, A. L. & Oltvai, Z. N. Lethality and centrality in protein networks. Nature 411, 41–2 (2001).

Poon, A. F. Y., Lewis, F. I., Frost, S. D. W. & Kosakovsky Pond, S. L. Spidermonkey: rapid detection of co-evolving sites using bayesian graphical models. Bioinformatics 24, 1949–50 (2008).

Zhang, Q. et al. Spread of Zika virus in the Americas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114, E4334–E4343 (2017).

Faria, N. R. et al. Establishment and cryptic transmission of zika virus in brazil and the americas. Nature 546, 406–410 (2017).

Tyler, A. L., Donahue, L. R., Churchill, G. A. & Carter, G. W. Weak epistasis generally stabilizes phenotypes in a mouse intercross. PLoS Genet 12, e1005805 (2016).

Waddington, C. H. Canalization of development and the inheritance of acquired characters. Nature 150, 563–565 (1942).

Faye, O. et al. Molecular evolution of Zika virus during its emergence in the 20(th) century. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8, e2636 (2014).

Aris-Brosou, S. Inferring influenza global transmission networks without complete phylogenetic information. Evol Appl 7, 403–12 (2014).

Labonté, K. & Aris-Brosou, S. Automatic detection of rate change in large data sets with an unsupervised approach: the case of influenza viruses. Genome 59, 253–62 (2016).

Bao, Y. et al. The influenza virus resource at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. J Virol 82, 596–601 (2008).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215, 403–10 (1990).

Gilbert, D. Sequence file format conversion with command-line readseq. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics Appendix 1, Appendix 1E (2003).

Zhao, B. et al. Structure and function of the Zika virus full-length NS5 protein. Nat Commun 8, 14762 (2017).

Edgar, R. C. Muscle: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32, 1792–7 (2004).

Larsson, A. AliView: a fast and lightweight alignment viewer and editor for large datasets. Bioinformatics 30, 3276–8 (2014).

Aris-Brosou, S. & Rodrigue, N. The essentials of computational molecular evolution. Methods Mol Biol 855, 111–52 (2012).

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. Fasttree 2–approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS One 5, e9490 (2010).

Paradis, E., Claude, J. & Strimmer, K. APE: analyses of phylogenetics and evolution in R language. Bioinformatics 20, 289–290 (2004).

Pond, S. L. K., Frost, S. D. W. & Muse, S. V. Hyphy: hypothesis testing using phylogenies. Bioinformatics 21, 676–9 (2005).

Kosakovsky Pond, S. L. & Frost, S. D. W. Not so different after all: a comparison of methods for detecting amino acid sites under selection. Mol Biol Evol 22, 1208–22 (2005).

Pearl, J. Probabilistic reasoning in intelligent systems: networks of plausible inference (Morgan Kaufmann, 1988).

Csardi, G. & Nepusz, T. The igraph software package for complex network research. InterJournal, Complex Systems 1695, 1–9 (2006).

Larsen, M. V. et al. Large-scale validation of methods for cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope prediction. BMC bioinformatics 8, 1 (2007).

Gu, Z., Gu, L., Eils, R., Schlesner, M. & Brors, B. Circlize implements and enhances circular visualization in R. Bioinformatics btu393 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank Jonathan Dench and George S. Long for discussions and comments, as well as two anonymous reviewers for additional comments. We also thank Compute Ontario and the Center for Advanced Computing for providing us access to their servers. This work was supported by the Natural Sciences Research Council of Canada and by the Canada Foundation for Innovation (S.A.B.) and by the University of Ottawa (N.I., J.N.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A.B. designed the study, and wrote the paper. S.A.B., N.I. and J.N. performed research and analyses, and edited the paper. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aris-Brosou, S., Ibeh, N. & Noël, J. Viral outbreaks involve destabilized evolutionary networks: evidence from Ebola, Influenza and Zika. Sci Rep 7, 11881 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12268-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12268-9

This article is cited by

-

COVID-19 Propagation Model Based on Economic Development and Interventions

Wireless Personal Communications (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.