Abstract

Premorbid social and academic adjustment are important predictors of cognitive and functional performance in schizophrenia. Whether this relationship is also present in individuals at ultra-high risk (UHR) for psychosis is the focus of the present study. Using baseline data from a randomised clinical trial (N = 146) this study investigated associations between premorbid adjustment and neuro- and social cognition and functioning in UHR individuals aged 18–40 years. Patients were evaluated with the Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS) comprising a social and an academic domain. Using validated measures neurocognition was assessed in the domains of processing speed, executive function, attention, verbal learning and memory, visual learning and memory, and working memory along with estimated IQ. Social cognitive domains assessed were theory of mind, emotion recognition, and attributional bias. Functional assessment comprised the domains of social- and role functioning, functional capacity, and quality of life. Linear regression analyses revealed poor premorbid academic adjustment to be associated with poorer performance in processing speed, working memory, attention, full scale IQ, and verbal IQ. Poor premorbid social adjustment was associated with theory of mind deficits. Additionally, both premorbid adjustment domains were associated with social- and role functioning and quality of life. Corroborating evidence from schizophrenia samples, our findings indicate poor premorbid adjustment to correlate with deficits in specific cognitive and functional domains in UHR states. Early premorbid adjustment difficulties may therefore indicate a poor cognitive and functional trajectory associated with significant impairments in early and established psychotic disorders suggesting targets for primary intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Poor premorbid adjustment is considered a key feature of psychotic disorders1,2,3,4,5,6,7 as it indicates the presence of neurodevelopmental anomalies prior to the onset of frank symptoms of psychosis8. More specifically, premorbid adjustment presents distinctive developmental trajectories, which, after onset of psychosis, follow paths of cognitive dysfunction and functional impairments9. Studies on psychotic disorders report associations between premorbid adjustment and functioning in the domains of global functioning, social functioning, and quality of life10,11,12,13. Moreover, cognitive dysfunction is one of the core features of schizophrenia spectrum disorders, and may be a likely marker of psychosis before the onset of the illness as demonstrated in familial high-risk (FHR) samples and general population samples14,15. Findings from schizophrenia studies reveal correlations between premorbid adjustment and general neurocognitive ability3,16, verbal learning and memory8,17,18,19, processing speed8, working memory8,10,17, executive function8,20, attention20, full scale IQ3, and verbal IQ8. Links have also been established between premorbid social adjustment and the social cognitive domains of social knowledge21, emotion recognition21, and theory of mind22. Notably, premorbid dysfunction is related to more severe post-onset cognitive impairments16,22,23. Premorbid adjustment difficulties may therefore indicate adverse clinical and cognitive trajectories in schizophrenia spectrum disorders and consequently represent an advantageous target for early intervention. However, while studies in clinical samples have shown associations between premorbid dysfunction and cognitive and functional impairments in individuals with schizophrenia3,8,10,16,17,18,20,22,24 these findings may be confounded by illness chronicity or antipsychotic use. Studying individuals before they reach a clinical psychotic state circumvents the confounds of living with a psychotic disorder. In this study, these individuals are considered at ultra-high risk (UHR) for psychosis thus constituting a clinical group with a subthreshold syndrome or a genetic vulnerability potentially leading to psychosis25,26,27. Poor premorbid adjustment has been established in UHR individuals28 and is a key feature of the premorbid period29. The importance of further elucidating on the premorbid phase in UHR state is accentuated by studies suggesting that poor premorbid academic and social adjustment may act as predictors of conversion to psychosis in UHR states30,31,32,33,34,35.

Similar to individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, UHR individuals exhibit significant impairments in neuro- and social cognition36,37,38 as well as in functioning39. Additionally, neuro- and social cognitive dysfunction have consistently been linked to severe functional impairments in UHR individuals and individuals with established psychosis40,41; Hence, these processes may thus be distinct but closely connected processes. The cognitive and functional impairments in UHR individuals have been reported to be potential predictors of transition to psychosis27,33,36,42,43,44,45,46. Furthermore, while numerous longitudinal FHR studies and general population studies have demonstrated early impairments, including cognitive and functional impairments, in individuals who develop psychotic disorder and those at FHR of psychosis5,15,47,48,49,50,51,52,53 conversion rates are substantially lower compared to UHR samples54,55,56. The current UHR design, therefore, enables the study of associations between premorbid adjustment and neuro- and social cognition and functioning close to potential illness onset in a cohort more enriched for risk, hence potentially contributing with valuable information to future primary intervention strategies. The aim of this paper is thus to extend the current knowledge on the impact of poor premorbid adjustment in psychosis spectrum disorders by exploring the relationship between premorbid adjustment and multiple areas of cognition and functioning in UHR states.

On the basis of the abovementioned research in schizophrenia spectrum disorders that has established links between premorbid academic adjustment and neurocognition and premorbid social adjustment and social cognition, we conducted exploratory analyses hypothesising that 1) poor premorbid academic adjustment would relate to neurocognitive deficits, and 2) poor premorbid social adjustment would relate to social cognitive deficits in UHR states. Finally, we hypothesised poor premorbid adjustment in both academic and social domains would relate to deficits in all aspects of current functioning.

Results

Of the 146 UHR participants in the study, 58.2% were females. They had a mean age of 23.92 (SD = 4.24). A majority (76%) fulfilled the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States (CAARMS)26 criteria of the attenuated psychotic symptom (APS), 20.5% fulfilled the criteria of APS + trait/state, 2.1% fulfilled the APS + brief limited intermittent psychotic symptom (BLIPS) criteria, and 1.4% fulfilled the trait/state criteria (See Table 1 for baseline characteristics).

Associations between premorbid academic adjustment and cognition and functioning

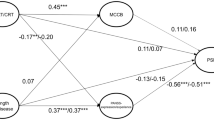

The linear regression analyses revealed that lower scores on premorbid academic adjustment were associated with slower processing speed and poorer attention (R2 = 0.05 and 0.05). Furthermore, poor premorbid academic adjustment was associated with lower working memory, though with a very small effect (R2 < 0.01). By extension, this association did not remain significant after correcting for multiple comparisons. Premorbid academic adjustment did not predict verbal learning and memory, visual learning and memory, or executive functions. Moreover, premorbid academic adjustment was related to lower full-scale IQ and verbal IQ (R2 = 0.13 and 0.14, respectively), but not performance IQ. Lastly, premorbid academic adjustment was related to reduced social- and role functioning, and quality of life but not functional capacity (R2 in the range of 0.05–0.12; See Table 2).

Associations between premorbid social adjustment and cognition and functioning

The linear regression analyses showed that lower scores on premorbid social adjustment were related to reduced theory of mind (R2 = 0.04) but not emotion recognition latency or accuracy, or attributional bias. Premorbid social adjustment was also associated with reduced social- and role functioning and poorer quality of life (R2 in the range of 0.02–0.18), but it did not relate to functional capacity (See Table 2).

Discussion

Supporting our first hypothesis, we found that poor premorbid academic adjustment in UHR individuals was associated with deficits in the neurocognitive domains of processing speed, working memory, and attention, along with full-scale IQ and verbal IQ. However, when corrected for multiple comparisons, the association between premorbid academic adjustment and working memory was not significant. Nonetheless, the links between poor academic adjustment and the neurocognitive domains are compatible with studies in schizophrenia reporting associations between premorbid adjustment and the same domains3,8,10,19,20. These studies, though, also reported associations between premorbid adjustment and verbal learning and memory and executive function3,8,10,19,20 beyond our findings. The correlation between poor premorbid academic adjustment and worse processing speed and attention is in line with a growing number of studies relating processing speed and attention to poor functional trajectory in the UHR population41,57,58,59. This indicates that processing speed and attention may be key cognitive aspects associated with functional impairments in UHR. Supporting the potential central role of poor processing speed in psychosis spectrum disorders, processing speed has been speculated to underlie generalised cognitive impairments and thus represent an important target for intervention60,61. The finding of premorbid academic functioning relating to estimated full-scale IQ and verbal IQ corresponds to findings in schizophrenia samples3,8. Poor premorbid academic adjustment reflects lower performance in school and an aversion to attend school62. In that respect, our results on associations between premorbid academic adjustment and neurocognition may imply that poor premorbid adjustment may set in motion a series of events that result in impaired neurocognitive processes in more pronounced psychopathological stages, i.e., UHR and established psychosis. This hypothesis is supported by the maturational nature of cognitive processes such as processing skills, working memory, attention, and aspects of IQ20,63,64,65. However, the reverse causality could also be a valid perspective as neurodevelopmental disturbances may interfere with premorbid adjustment causing individuals not to thrive in school10,16. Regardless of the causality, our findings add to the notion that premorbid academic dysfunction across childhood and adolescence relates to neurocognitive dysfunction in putative prodromal and established psychotic disorders. This supports the idea of early manifestations of poor academic adjustment potentially being involved in early abnormal cognitive developmental trajectory specific to developing psychosis several years prior to illness onset66.

We did not find associations between poor premorbid academic adjustment and verbal learning and memory, executive functions, visual learning and memory, or performance IQ. This may be explained by the notion of early versus late neurodevelopmental processes in which some cognitive areas like processing speed67, working memory68,69, and attention70 are regarded as basic cognitive domains with early maturational attainment. Other higher-order abilities like executive functions and verbal skills are instead still being refined throughout young adulthood and hence might not be influenced by poor academic adjustment in early years70,71.

Partly corroborating our second hypothesis, we found poor premorbid social adjustment to be associated with social cognition albeit only in the domain of theory of mind, and not emotion recognition or attributional bias. The relationship between premorbid social adjustment and theory of mind is compatible with findings from a schizophrenia study showing a significant link between these domains22. Speculating, children or adolescents struggling with social functioning in their premorbid years might persist having theory of mind deficits at UHR stages since poor premorbid social adjustment involves having few friends (if any) or not enjoying spending time with peers. This potentially limits development of theory of mind entailing impaired abilities later in life. Unfortunately, we were not able to show a significant association between premorbid social adjustment and emotion recognition, which have been reported in a schizophrenia study21. Neither did we find an association between premorbid social adjustment and deficits in attributional bias, albeit this could be due to dissatisfying psychometric properties of available measures of this domain72. Moreover, it must be noted that we only assessed social cognitive function in three of the hypothesised four social cognitive domains72. Future studies should therefore examine the relationship between the premorbid adjustment scale and all four core aspects of social cognition to reach more firm conclusions on this potential relationship.

Lastly, in partial correspondence with our third hypothesis, we found both poor premorbid academic and social adjustment to relate to impairments in social- and role functioning and quality of life but not with respect to functional capacity. Hence, individuals exhibiting poor adjustment in school and/or with peers in their childhood and adolescence, may be at risk for a poor functional trajectory. This notion is supported by studies in the schizophrenia population reporting associations between premorbid adjustment and global functioning, social functioning, and quality of life, thus suggesting poor premorbid adjustment will persist at post-illness onset10,11,12,13. Contrary to the strong association between premorbid adjustment and social- and role functioning and quality of life, we only found a trending association with social skills functional capacity. This could be explained by the High Risk Social Challenge Task (HiSoC)73 being suboptimal due to issues with tolerability and acceptability57 warranting further studies on this association using other functional capacity measures.

The current study must be considered within the context of potential limitations. First, it should be acknowledged that use of the term “premorbid” in this paper and in the wider literature is debatable. It is generally used to refer to the period before onset of psychotic symptoms that clearly indicate presence of a diagnosable psychotic illness. It can be argued that aspects of social and academic adjustment before diagnosis simply reveal early signs of the disorders, hence not being genuinely premorbid. From this outlook, aspects of premorbid social adjustment could reflect early negative symptoms often occurring before onset of positive symptoms. Premorbid academic adjustment could likewise, at least partially, reflect early neurocognitive impairment perhaps being an essential part of psychosis. Potentially limiting the findings is the retrospective design of the PAS62, although predictive and concurrent validity of the instrument have been established74. However, applying the PAS in a UHR sample is advantageous as the individuals are close in age to the developmental periods of interest and, as beforementioned, they have not reached a manifested psychotic state thus circumventing the confounds of living with a psychotic disorder. These aspects may limit the potential recall bias on the PAS. We acknowledge that our sample may be an older age range compared to other UHR studies (e.g.34), which may impact generalisability of our findings to the entire UHR population. Additionally, it must be acknowledged that PAS_academic and PAS_social only explain a modest proportion of the variability on neurocognition and social cognition, respectively, as well as on functioning. Finally, including multiple outcome measures in our analyses may involve a potential risk for multiplicity involving the risk of significant associations being spurious. Hence, our findings should be evaluated within a hypothesis-generating, exploratory perspective with p-values close to 0.05 being appraised cautiously. However, as cognition and functioning are multifaceted constructs, it is relevant to include multiple measures capturing the different aspects of these domains.

To conclude, our findings indicate that premorbid adjustment relates to distinct neurocognitive, social cognitive, and functional aspects in the UHR population. Our findings thus highlight the relevance of focusing on premorbid adjustment in clinical research as well as in early intervention preventive approaches. In keeping with the abovementioned evidence from other studies, our findings point to the premorbid period in childhood and adolescence as being a time where neurodevelopmental vulnerability is evident. At this early stage the individuals could be particularly responsive to psychosocial or pharmacological intervention48,75,76. While the current study extends findings from schizophrenia samples to UHR samples on important links between poor premorbid adjustment and cognitive and functional deficits, future studies should replicate our findings. Future studies should also elucidate on poor premorbid adjustment in relation to multiple aspects of social cognition using psychometrically well-validated instruments.

Methods

Data applied in this study were baseline data from a randomised clinical trial (RCT) examining the effect of cognitive remediation in UHR individuals. These analyses are thus secondary to the RCT. Recruitments were from psychiatric in- and outpatient facilities in the greater catchment area of Copenhagen, Denmark, from April 2014 to December 2017. Trial protocol was approved by the Committee on Health Research Ethics of the Capital Region Denmark (study: H-6-2013-015). All participants provided informed written consent prior to the study.

Participants

The sample consisted of help-seeking individuals aged 18–40 years meeting one or more of the UHR criteria according to the CAARMS26: the APS group, the BLIPS group, and/or the trait and vulnerability group along with a significant drop in functioning or sustained low functioning for the past year. Individuals were excluded if they had a history of a psychotic episode of ≥1-week duration, experienced psychiatric symptoms explained by a physical illness with psychotropic effect (e.g., delirium) or acute intoxication (e.g., cannabis use), had a diagnosis of a serious developmental disorder such as Asperger’s syndrome or mental retardation with an IQ < 70, or currently were treated with methylphenidate.

Assessments

Clinical

APS level was assessed with the CAARMS scale comprising a global rating scale (ranging 0–6 where 0 is no symptoms present) and a frequency scale (ranging 0–6 where 0 is no occurrence)26. A CAARMS composite score was calculated according to the formula (Iutc ∗ Futc) + (Inbi ∗ Fnbi) + (Ipa ∗ Fpa) + (Ids ∗ Fds)77,78 range 0–144. CAARMS composite score was computed by weighing intensity of symptoms by their frequency79.

Premorbid adjustment

Premorbid adjustment was evaluated using a Danish translation of the premorbid adjustment scale (PAS)62; An interview-based rating schedule for assessing functioning, particularly social and academic functioning, across four developmental stages: childhood (up to 11 years), early adolescence (12–15 years), late adolescence (16–18 years) and adulthood (19 years and counting). The social adjustment domain consists of items from three domains, a) sociability/withdrawal, b) peer relationships, and c) ability to form interpersonal and sexual ties (only assessed in adolescence). The academic adjustment domain consists of items from two domains: achievement in school and adaption to school. As this study did not focus on specific age periods, we used a PAS “composite” score assembling all four age periods into one overall premorbid stage. This means that we did not distinguish between childhood, early adolescence, late adolescence, and adulthood in the premorbid period. The general information section and adulthood subscale were not included in the statistical analysis to avoid including symptoms of the prodromal phase. Moreover, items of sociosexual adaption were not included since these do not cover childhood19. Based on participants’ own statements, each item is rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 0 to 6, with 0 indicating healthy function and 6 denoting maximum adjustment deficits. According to PAS the premorbid period was defined as ending six months before first psychiatric contact or before the appearance of psychosis-like symptoms. Predictive and concurrent validity of the PAS has shown to be satisfactory74.

Functioning

Four measures were included covering functional aspects of social- and role functioning, self-reported quality of life, and performance-based functional capacity social skills. The Global Functioning: Social and Role Scales30 were used to assess social- and role functioning with a range from 1 to 10. On these scales, higher scores indicate better functioning levels. The scales have been developed specifically to assess functioning in the putative prodromal state of psychosis with age-appropriate anchors for assessing functioning in UHR.

Quality of life was reported with the Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL-8D)80, which is a self-report measure, including physical (e.g., independent living and pain) and psycho-social (e.g., happiness, relationships, and coping) overarching dimensions. A composite quality of life score was used in the analyses but domain scores can be extracted from the instrument. The AQoL-8D has been used in another large-scale UHR trial81. Finally, the performance-based test HiSoC73 was included, measuring functional capacity of social skills such as display of affect, odd behaviour and language, social interpersonal anxiety, and task engagement. It is a standardised videotaped task in which the participants are instructed to do a 45-second audition in a mock competition, with a grand money prize, on being the most interesting person in the country. The task’s 16 items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale with higher scores indicating better social skills. HiSoC has demonstrated excellent reliability and validity in UHR82.

Cognition

The neurocognitive tests included cover six core neurocognitive domains as stated in the National Institute of Mental Health Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) battery77. List learning and symbol coding from the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (battery indexes verbal learning and memory and processing speed. Tests from Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB)78 were Paired Associate Learning (PAL) indexing visual learning and memory, Spatial Working Memory (SWM) indexing working memory, Stockings of Cambridge (SOC) indexing executive function, and Rapid Visual Information Processing indexing sustained attention. Except for PAL and SWM the measures are expressed in the same direction, meaning that higher scores indicate a better cognitive performance. PAL and SWM measure number of errors on the task; hence, on these tasks a lower score indicates a better performance. To cover the seventh domain of the MATRICS battery, social cognition, we included four social cognitive measures covering three social cognitive domains72: Theory of mind with The Awareness of Social Inference Test83; attributional bias with Social Cognition Screening Questionnaire84; and facial emotion recognition accuracy and latency with Emotion Recognition Task of the CANTAB battery85. Current IQ was estimated using four subtests from Danish Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale Version 3 (WAIS-III), namely Vocabulary, Similarities, Block Design, and Matrix reasoning86 which are known to correlate strongly with full-scale IQ87. Based on these four subscales three outcomes measured were: verbal intelligence, performance intelligence, and an overall measure combining these two subscales. WAIS-III was administered and scored according to the standardised procedures specified by its manual.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0. Descriptive statistics were reported as means and standard deviations. Data were examined for normal distribution and outliers. Linear univariate regression analyses were performed to investigate associations between premorbid social and academic adjustment and the domains of neurocognition, social cognition, and functioning at baseline. Significance levels were set to p < 0.05. As we examined associations between premorbid adjustment and cognition and functioning, PAS_academic and PAS_social were set as independent variables in the regression analyses with covariates of age, sex, and medication (antipsychotic, antidepressant, mood stabilisers, or benzodiazepines). Measures of cognition and functioning were dependent variables. We included one independent variable with the covariates and one dependent variable per model. Significance was corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamin-Hochberg procedure88 with a false discovery rate of 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Tarbox, S. I., Haas, G. & Brown, L. Premorbid adjustment in affective and non-affective psychosis: a first episode study. Schizophr. Bull. 37, 21–22 (2011).

Kraepelin, E. Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia. (Krieger, 1919).

Allen, D. N., Kelley, M. E., Miyatake, R. K., Gurklis, J. A. & van Kammen, D. P. Confirmation of a two-factor model of premorbid adjustment in males with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 27, 39–46 (2001).

Allen, D. N., Frantom, L. V., Strauss, G. P. & van Kammen, D. P. Differential patterns of premorbid academic and social deterioration in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 75, 389–397 (2005).

Cannon, M. et al. Evidence for early-childhood, pan-developmental impairment specific to schizophreniform disorder: results from a longitudinal birth cohort. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 59, 449 (2002).

Reichenberg, A. The assessment of neuropsychological functioning in schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 12, 383–392 (2010).

Reichenberg, A. et al. A population-based cohort study of premorbid intellectual, language, and behavioral functioning in patients with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and nonpsychotic bipolar disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 159, 2027–2035 (2002).

Stefanatou, P. et al. Premorbid adjustment predictors of cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 267, 249–255 (2018).

Norman, R. M. G., Malla, A. K., Manchanda, R. & Townsend, L. Premorbid adjustment in first episode schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders: a comparison of social and academic domains. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 112, 30–39 (2005).

Larsen, T. K. et al. Premorbid adjustment in first-episode non-affective psychosis: distinct patterns of pre-onset course. Br. J. Psychiatry 185, 108–115 (2004).

Malla, A. K., Norman, R. M. G., Manchanda, R. & Townsend, L. Symptoms, cognition, treatment adherence and functional outcome in first-episode psychosis. Psychol. Med. 32, 1109–1119 (2002).

Bromet, E. J. et al. The Suffolk County Mental Health Project: demographic, pre-morbid and clinical correlates of 6-month outcome. Psychol. Med. 26, 953–962 (1996).

Del Rey-Mejías, Á. et al. Functional deterioration from the premorbid period to 2 years after the first episode of psychosis in early-onset psychosis. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 24, 1447–1459 (2015).

Jonas, K. et al. The course of general cognitive ability in individuals with psychotic disorders. JAMA Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.1142 (2022).

Bora, E. et al. Cognitive deficits in youth with familial and clinical high risk to psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 130, 1–15 (2014).

Cuesta, M. J. et al. Premorbid adjustment and clinical correlates of cognitive impairment in first-episode psychosis. The PEPsCog Study. Schizophr. Res. 164, 65–73 (2015).

Addington, J. & Addington, D. Patterns of premorbid functioning in first episode psychosis: relationship to 2-year outcome. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 112, 40–46 (2005).

Chang, W. C. et al. Impacts of duration of untreated psychosis on cognition and negative symptoms in first-episode schizophrenia: a 3-year prospective follow-up study. Psychol. Med. 43, 1883–1893 (2013).

Rund, B. R. et al. The course of neurocognitive functioning in first-episode psychosis and its relation to premorbid adjustment, duration of untreated psychosis, and relapse. Schizophr. Res. 91, 132–140 (2007).

Silverstein, M. L., Mavrolefteros, G. & Close, D. Premorbid adjustment and neuropsychological performance in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 28, 157–165 (2002).

Dewangan, R. L. & Singh, P. Premorbid adjustment in predicting symptom severity and social cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. East Asian Arch. Psychiatry 28, 75–79 (2018).

Schenkel, L. S., Spaulding, W. D. & Silverstein, S. M. Poor premorbid social functioning and theory of mind deficit in schizophrenia: evidence of reduced context processing? J. Psychiatr. Res. 10, 499–508 (2005).

Chang, W. C. et al. The relationship of early premorbid adjustment with negative symptoms and cognitive functions in first-episode schizophrenia: A prospective three-year follow-up study. Psychiatry Res. 209, 353–360 (2013).

Dewangan, R. & Singh, P. Severity and social cognitive deficits 28, 75–79 (2018).

Fusar-Poli, P. et al. The psychosis high-risk state: a comprehensive state-of-the-art review. JAMA Psychiatry 70, 107 (2013).

Yung, A. R. et al. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the comprehensive assessment of at-risk mental states. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 8, 964–971 (2005).

Yung, A. R., Phillips, L. J., Yuen, H. P. & McGorry, P. D. Risk factors for psychosis in an ultra high-risk group: psychopathology and clinical features. Schizophr. Res. 12, 131–142 (2004).

Dannevang, A. L. et al. Premorbid adjustment in individuals at ultra-high risk for developing psychosis: a case-control study: premorbid adjustment in ultra-high risk individuals. Early Interv. Psychiatry 12, 839–847 (2018).

Tarbox, S. I. & Pogue-Geile, M. F. Development of social functioning in preschizophrenia children and adolescents: a systematic review. Psychol. Bull. 134, 561–583 (2008).

Cornblatt, B. A. et al. Preliminary findings for two new measures of social and role functioning in the prodromal phase of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 33, 688–702 (2007).

MacBeth, A. & Gumley, A. Premorbid adjustment, symptom development and quality of life in first episode psychosis: a systematic review and critical reappraisal: premorbid adjustment in psychosis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 117, 85–99 (2007).

MacCabe, J. H. et al. Scholastic achievement at age 16 and risk of schizophrenia and other psychoses: a national cohort study. Psychol. Med. 38, 1133–1140 (2008).

Dragt, S. et al. Environmental factors and social adjustment as predictors of a first psychosis in subjects at ultra high risk. Schizophr. Res. 125, 69–76 (2011).

Tarbox, S. I. et al. Premorbid functional development and conversion to psychosis in clinical high-risk youths. Dev. Psychopathol. 25, 1171–1186 (2013).

Kendler, K. S., Ohlsson, H., Mezuk, B., Sundquist, K. & Sundquist, J. A Swedish national prospective and co-relative study of school achievement at age 16, and risk for schizophrenia, other nonaffective psychosis, and bipolar illness. Schizophr. Bull. 103 https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbv103 (2015).

Fusar-Poli, P. et al. Cognitive functioning in prodromal psychosis: a meta-analysis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 69, 562–571 (2012).

Lee, T. Y., Hong, S. B., Shin, N. Y. & Kwon, J. S. Social cognitive functioning in prodromal psychosis: a meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 164, 28–34 (2015).

van Donkersgoed, R. J. M., Wunderink, L., Nieboer, R., Aleman, A. & Pijnenborg, G. H. M. Social cognition in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 10, e0141075 (2015).

Fusar-Poli, P. et al. Disorder, not just state of risk: meta-analysis of functioning and quality of life in people at high risk of psychosis. Br. J. Psychiatry 207, 198–206 (2015).

Green, M. F., Kern, R. S., Braff, D. L. & Mintz, J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the ‘right stuff’? Schizophr. Bull. 26, 119–136 (2000).

Bolt, L. K. et al. Neurocognition as a predictor of transition to psychotic disorder and functional outcomes in ultra-high risk participants: findings from the NEURAPRO randomized clinical trial. Schizophr. Res. 206, 67–74 (2019).

Kim, H. S. et al. Social cognition and neurocognition as predictors of conversion to psychosis in individuals at ultra-high risk. Schizophr. Res. 130, 170–175 (2011).

Corcoran, C. M. et al. The relationship of social function to depressive and negative symptoms in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Psychol. Med. 41, 251–261 (2011).

Cornblatt, B. A. et al. Risk factors for psychosis: impaired social and role functioning. Schizophr. Bull. 38, 1247–1257 (2012).

Mason, O. et al. Risk factors for transition to first episode psychosis among individuals with ‘at-risk mental states’. Schizophr. Res. 71, 227–237 (2004).

Yung, A. R. et al. Psychosis prediction: 12-month follow up of a high-risk (“prodromal”) group. Schizophr. Res. 60, 21–32 (2003).

Hameed, M. A. & Lewis, A. J. Offspring of parents with schizophrenia: a systematic review of developmental features across childhood. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 24, 104–117 (2016).

Liu, C. H., Keshavan, M. S., Tronick, E. & Seidman, L. J. Perinatal risks and childhood premorbid indicators of later psychosis: next steps for early psychosocial interventions. Schizophr. Bull. 41, 801–816 (2015).

Sandstrom, A., Sahiti, Q., Pavlova, B. & Uher, R. Offspring of parents with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression: a review of familial high-risk and molecular genetics studies. Psychiatr. Genet. 29, 160–169 (2019).

Laurens, K. R. et al. Common or distinct pathways to psychosis? A systematic review of evidence from prospective studies for developmental risk factors and antecedents of the schizophrenia spectrum disorders and affective psychoses. BMC Psychiatry 15, 205 (2015).

Gregersen, M. et al. Mental disorders in preadolescent children at familial high‐risk of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder—a four‐year follow‐up study: The Danish High Risk and Resilience Study, VIA 11. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 13548 https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13548 (2021).

Knudsen, C. B. et al. Neurocognitive development in children at familial high risk of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 79, 589 (2022).

De la Serna, E. et al. Lifetime psychopathology in child and adolescent offspring of parents diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: a 2-year follow-up study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 30, 117–129 (2021).

Fusar-Poli, P. et al. Prevention of psychosis: advances in detection, prognosis, and intervention. JAMA Psychiatry 77, 755 (2020).

Pedersen, C. B. et al. A comprehensive nationwide study of the incidence rate and lifetime risk for treated mental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 71, 573 (2014).

Rasic, D., Hajek, T., Alda, M. & Uher, R. Risk of mental illness in offspring of parents with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of family high-risk studies. Schizophr. Bull. 40, 28–38 (2014).

Glenthøj, L. B., Kristensen, T. D., Wenneberg, C., Hjorthøj, C. & Nordentoft, M. Investigating cognitive and clinical predictors of real-life functioning, functional capacity, and quality of life in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. Open 1, sgaa027 (2020).

Lin, A. Neurocognitive predictors of functional outcome two to 13 years after identification as ultra-high risk for psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 7, 1–7 (2011).

Niendam, T. A. et al. The course of neurocognition and social functioning in individuals at ultra high risk for psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. 33, 772–781 (2007).

Gonzalez-Blanch, C. et al. A digit symbol coding task as a screening instrument for cognitive impairment in first-episode psychosis. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 26, 48–58 (2011).

Randers, L. et al. Generalized neurocognitive impairment in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis: the possible key role of slowed processing speed. Brain Behav. 11, 1–10 (2021).

Cannon-Spoor, H. E., Potkin, S. G. & Wyatt, R. J. Measurement of premorbid adjustment in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 8, 470–484 (1982).

Craik, F. I. M. & Bialystok, E. Cognition through the lifespan: mechanisms of change. Trends Cogn. Sci. 10, 131–138 (2006).

Hoekstra, R. A., Bartels, M. & Boomsma, D. I. Longitudinal genetic study of verbal and nonverbal IQ from early childhood to young adulthood. Learn. Individ. Differ. 17, 97–114 (2007).

van Soelen, I. L. C. et al. Heritability of verbal and performance intelligence in a pediatric longitudinal sample. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 14, 119–128 (2011).

Kahn, R. S. & Keefe, R. S. E. Schizophrenia is a cognitive illness: time for a change in focus. JAMA Psychiatry 70, 1107 (2013).

Luna, B., Garver, K. E., Urban, T. A., Lazar, N. A. & Sweeney, J. A. Maturation of cognitive processes from late childhood to adulthood. Child Dev. 75, 1357–1372 (2004).

Wood, S. J. et al. Spatial working memory ability is a marker of risk-for-psychosis. Psychol. Med. 33, 1239–1247 (2003).

Pantelis, C., Wannan, C., Bartholomeusz, C. F., Allott, K. & McGorry, P. D. Cognitive intervention in early psychosis—preserving abilities versus remediating deficits. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 4, 63–72 (2015).

De Luca, C. R. et al. Normative data from the Cantab. I: development of executive function over the lifespan. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 25, 242–254 (2003).

Paus, T. Mapping brain maturation and cognitive development during adolescence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9, 60–68 (2005).

Pinkham, A. E. et al. The social cognition psychometric evaluation study: results of the expert survey and RAND panel. Schizophr. Bull. 40, 813–823 (2014).

Gibson, C. M., Penn, D. L., Prinstein, M. J., Perkins, D. O. & Belger, A. Social skill and social cognition in adolescents at genetic risk for psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 122, 179–184 (2010).

Brill, N., Reichenberg, A., Weiser, M. & Rabinowitz, J. Validity of the premorbid adjustment scale. Schizophr. Bull. 34, 981–983 (2008).

Arango, C. et al. Preventive strategies for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 5, 591–604 (2018).

Seidman, L. J. & Nordentoft, M. New targets for prevention of schizophrenia: is it time for interventions in the premorbid phase? Schizophr. Bull. 41, 795–800 (2015).

Nuechterlein, K. H. et al. Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 72, 29–39 (2004).

Strauss, E., Sherman, E. M. S., Spreen, O. & Spreen, O. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests: Administration, Norms, and Commentary. (Oxford University Press, 2006).

Lim, J. et al. Impact of psychiatric comorbidity in individuals at Ultra High Risk of psychosis—findings from the Longitudinal Youth at Risk Study (LYRIKS). Schizophr. Res. 164, 8–14 (2015).

Richardson, J., Iezzi, A., Khan, M. A. & Maxwell, A. Validity and reliability of the assessment of quality of life (AQoL)-8D multi-attribute utility instrument. Patient - Patient-Centered Outcomes Res. 7, 85–96 (2014).

Markulev, C. et al. NEURAPRO-E study protocol: a multicentre randomized controlled trial of omega-3 fatty acids and cognitive-behavioural case management for patients at ultra high risk of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Early Interv. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12260 (2015).

Glenthøj, L. B., Kristensen, T. D., Gibson, C. M., Jepsen, J. R. M. & Nordentoft, M. Assessing social skills in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis: validation of the High Risk Social Challenge task (HiSoC). Schizophr. Res. 215, 365–370 (2020).

McDonald, S., Flanagan, S., Rollins, J. & Kinch, J. TASIT: a new clinical tool for assessing social perception after traumatic brain injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 18, 219–238 (2003).

Roberts, D. L., Fiszdon, J. & Tek, C. Ecological validity of the social cognition screening questionnaire (scsq). In Schizophr. Bull. 37, 280–280 (2011).

Sahakian, B. J. & Owen, A. M. Computerized assessment in neuropsychiatry using CANTAB: discussion paper. J. R. Soc. Med. 85, 399–402 (1992).

Wechsler, D. & Psychological Corporation. WAIS-III: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. (Psychological Corp., 1997).

Axelrod, B. N. Validity of the Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence and other very short forms of estimating intellectual functioning. Assessment 9, 17–23 (2002).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 57, 289–300 (1995).

Acknowledgements

The study has been funded through The Danish Council for Independent Research (DFF-4004-00314); TrygFonden (ID 108119); the Mental Health Services in the Capital Region of Denmark; the research fund of the Capital Region of Denmark; the Lundbeck Foundation Center for Clinical Intervention and Neuropsychiatric Schizophrenia Research, CINS (R155-2013-16337).

Funding

Det Frie Forskningsråd, Grant/Award Number: DFF-4004-00314; Lundbeckfonden Center for Clinical Intervention and Neuropsychiatric Schizophrenia Research, CINS, Grant/Award Number: R155-2013-16337; Region Hovedstaden Forskningsfond, Grant/Award Number: -; the Mental Health Services in the Capital Region of Denmark; TrygFonden, Grant/Award Number: ID 108119.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.B.G. and M.N. conceived the study. L.B.G., T.D.K., and C.W. performed the data acquisition. L.B.G. and J.L. interpreted the data. J.L. wrote the paper supervised by L.B.G. M.G. contributed with interpretation of data with a specific focus on high-risk stages. All authors approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lundsgaard, J., Kristensen, T.D., Wenneberg, C. et al. Premorbid adjustment associates with cognitive and functional deficits in individuals at ultra-high risk of psychosis. Schizophr 8, 79 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-022-00285-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-022-00285-1

This article is cited by

-

Risk and protective factors for recovery at 3-year follow-up after first-episode psychosis onset: a multivariate outcome approach

Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology (2023)