Abstract

This systematic review provides a comprehensive overview of the association between premorbid adjustment and social cognition in people with psychotic spectrum disorder. Obtaining evidence of this association will facilitate early detection and intervention before the onset of psychosis. Literature searches were conducted in Scopus, PubMed and PsycINFO. Studies were eligible if they included patients with a psychotic disorder or at a high-risk state; social cognition and premorbid adjustment were measured; and the relationship between premorbid adjustment and social cognition was analysed. The authors independently extracted data from all included articles, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Literature searches were conducted in Scopus, PubMed and PsycINFO. Studies were eligible if they included patients with a psychotic disorder or at a high-risk state; social cognition and premorbid adjustment were measured; and the relationship between premorbid adjustment and social cognition was analysed. The authors independently extracted data from all included articles, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Of 229 studies identified, 23 met the inclusion criteria. Different methods of assessment were used to measure premorbid adjustment, such as the Premorbid Adjustment Scale or premorbid IQ, among others. Social cognition was assessed as a global measure or by domains using different instruments. A total of 16 articles found a relationship between social cognition (or its domains) and premorbid adjustment: general social cognition (n = 3); Theory of Mind (n = 12); Emotional Recognition and Social Knowledge (n = 1). This review shows evidence of a significant relationship between social cognition and premorbid adjustment, specifically between Theory of Mind and premorbid adjustment. Social cognition deficits may already appear in phases prior to the onset of psychosis, so an early individualized intervention with stimulating experiences in people with poor premorbid adjustment can be relevant for prevention. We recommend some future directions, such as carrying out longitudinal studies with people at high-risk of psychosis, a meta-analysis study, broadening the concept of premorbid adjustment, and a consensual assessment of social cognition and premorbid adjustment variables. PROSPERO registration number: CRD42022333886.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Early detection and intervention before the onset of psychosis can have a positive impact on overall outcomes, symptoms and global functioning1. It is crucial to understand how the clinical debut of patients with psychosis occurs to study the relationship between present difficulties and difficulties in the past. Evidence of this link can provide adequate intervention and preventive strategies for psychosis.

Reduced cognitive function at an early age and academic underperformance are studied risk factors for developing schizophrenia2. A poorer premorbid adjustment has been described as a risk factor of poor outcome in early-onset psychosis3.

The first definitions of premorbid adjustment in schizophrenia contemplated the characteristics of a person, especially interpersonal relations and occupational functioning before the onset of schizophrenia4. Recent approaches consider that premorbid adjustment integrates psychosocial functioning in educational, occupational, social, and interpersonal relation areas5,6, considering premorbid adjustment a multidimensional factor. Dewangan et al.7 described premorbid adjustment as a combination of peer and social relationships, school adaptation, job functioning and opposite-sex relationship before the development of schizophrenia. Scientific evidence supports the existence of at least two domains of premorbid adjustment: academic and social, each of which has different correlates. For example, academic functioning is associated with neurocognitive functioning8,9,10. In this review, instead of academic premorbid adjustment, we considered a broader term: cognitive premorbid adjustment, which includes subjective information (academic premorbid adjustment), measured by a scale, and objective information (premorbid IQ), measured by a cognitive test.

Neurocognition encompasses all the basic processes that allow a person to learn about, understand, and know the world they live in11. Research in schizophrenia has identified eight separate neurocognitive domains, one of which is social cognition12. According to Green et al.13, social cognition has been defined as the mental operations underlying social interactions, such as perceiving, interpreting, and generating responses to the intentions and behaviours of others. There is consensus on four core domains of social cognition: emotion processing, social perception, Theory of Mind (mental state attribution) and attributional style/bias14. Emotion processing is defined as perceiving and using emotions. Social perception/knowledge refers to decoding and interpreting social cues in others. Theory of Mind is the ability to represent the mental states of others, including the inference of intentions and beliefs. Attributional style describes the way in which individuals explain the causes or make sense of social events or interactions.

There are no previous systematic reviews that study the relationship between social cognition and premorbid adjustment in people with psychosis. It has been described that social cognition is associated with social functional outcome15, but there is very scarce literature studying the relationship between social cognition and premorbid adjustment.

The aim of this review is to assess the relationship between social cognition after the onset of psychosis and premorbid adjustment in people with psychotic spectrum disorder. The specific aim of the study is to systematically review the relationship between social and academic premorbid adjustment and social cognition, and its domains in people with psychotic spectrum disorder. The finality of studying the link of social cognition and premorbid adjustment will give evidence to study the predictive capacity of the course of psychosis, help clinicians achieve early detection, and design tailored intervention and prevention strategies to improve the prognosis of psychosis.

Material And Methods

Search strategy

The protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42022333886) and PRISMA guidelines were followed16. We employed the PsycINFO, PubMed and SCOPUS databases to search for articles examining the relationship between premorbid adjustment and social cognition published from inception to June 2022. In this review, premorbid adjustment includes both domains: social and cognitive premorbid adjustment. We considered that cognitive premorbid adjustment includes academic premorbid performance, measured by a scale, and premorbid IQ, measured by a cognitive test. Social cognition includes general assessment and each of its components: emotion processing, social perception, Theory of Mind and attributional bias.

The search covered the combination of three concepts: our target population (psychotic disorders or people at risk of psychosis), functioning in the premorbid period of psychosis, and social cognition. The search string used in the three databases was: (“social cognition” OR “ToM” OR “Theory of Mind” OR “attributional style” OR “attribution style” OR “emotional recognition” OR “emotion recognition” OR “facial recognition” OR “emotional processing” OR “social perception” OR “emotion perception” OR “affect perception” OR “affect recognition” OR “mentalizing” OR “mentalising” OR “attributions” OR “social knowledge” OR “social cue recognition” OR “emotion identification”) AND (“premorbid adjustment” OR “premorbid functioning” OR “premorbid deterioration” OR “premorbid”) AND (“first-episode schizophrenia” OR “first-episode psychosis” OR “early psychosis” OR “schizophrenia” OR “first episode psychosis” OR “non-affective psychosis” OR “nonaffective psychosis” OR “psychosis” OR “at-risk” OR “ultra-high risk” OR “clinical risk” OR “high risk”). Boolean operators were used to perform a more specific search. Three authors (SO, PP and AB) inspected the references of the included articles.

Further manual searches of the references of the relevant studies and reviews were undertaken by authors.

Screening and selection criteria

During screening, all authors reviewed titles and abstracts retrieved. Conflicts were reviewed and discussed until consensus. Doubtful articles were included for subsequent full-text review. In the second phase, two of the authors reviewed each article included in the screening phase. Studies were eligible if (i) the sample included patients with psychotic disorder or at high-risk state for psychosis. Given the growing interest in social cognition during psychosis and in its prodromal phase13,17,18,19,20,21,22, the full spectrum of psychotic disorders and high-risk states were included; (ii) social cognition (or any component), and premorbid adjustment were measured. Any method of assessment was permitted, such as medical chart reviews or school reports to inform about cognitive premorbid adjustment; and (iii) the relationship between premorbid adjustment and social cognition or its components were analyzed. This association might not be the main aim of studies. The search was limited to studies published in English or Spanish. Premorbid adjustment or social cognition analyzed as control variables as well as qualitative designs were excluded.

Data collection process

The authors independently extracted data from all included articles, and discrepancies were resolved via discussion. Data extracted included: (i) first author and year of publication, (ii) aims, (iii) target population and sample size, (iv) assessment methods, (v) outcome variables regarding the aim of this systematic review; (vi) main findings regarding the aim of this systematic review; (vii) general conclusion through a specific question: Is there a relationship between premorbid adjustment and social cognition, and (viii) risk of bias. The risk bias of the articles included in the review was performed by the authors using the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Study Quality Assessment Tools23. Our research group had previously adapted the instrument to better capture the strengths and weaknesses of the studies24. The classification of the observational and cross-sectional studies was: “Good” (more than 9 positive answers), “Fair” (between 7 and 9 positive answers), or “Poor” (below 7 positive answers). The classification of the before and after studies was: “Good” (more than 8 positive answers), “Fair” (between 6 and 8 positive answers), or “Poor” (below 6 positive answers). A different cutoff was decided because, in the case of cross-sectional studies, the total number of items assessed was 14, and in the case of before and after studies, it was 12 items. If any information was not applicable or specified, the final risk of bias score was weighted, taking into account only items with yes/no answers.

Results

Study selection

We identified 229 citations. After eliminating duplicates, we included 133 potentially relevant papers. Two evaluators assessed each paper. In a total of 16 papers, two evaluators assessed differently, and the article was reviewed by another member of the team. The percentage of agreement was 88.54% (kappa index of 0.75). After screening, 40 papers were selected, and the full text was retrieved. A total of 23 studies met the inclusion criteria for the final review. Regarding the 17 articles eliminated, 15 of them were because the authors did not analyze the relationship between premorbid adjustment and social cognition, although in 13 of them, they included both constructs, but the aims of the manuscript were different from their relationship. In 2 of them, the sample of the study did not meet the criteria of our review. A flowchart detailing the identification of studies is provided in Fig. 1.

Study characteristics

Relevant data extracted from the 23 studies are compiled in Table 1. Of them, 14 articles studied premorbid adjustment using the Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS)6 instrument, and seven assessed premorbid adjustment as premorbid IQ. The remaining articles used other measures, such as medical chart reviews25 and the Abbreviated Scale of Premorbid Personal-Social Adjustment26. In all the studies, the data indicated premorbid adjustment is obtained based on the previous period of the psychosis onset. In the case of premorbid IQ, it has been estimated using scales that remain stable after the psychosis episode (for instance, vocabulary subtest of WAIS).

Regarding social cognition, 18 studies analyzed specific domains: 12 studies included Theory of Mind, and six measured more than one domain of social cognition. Five studies used a global measure of social cognition.

As for diagnosis, 17 articles used a sample of individuals with schizophrenia, and six studies included a sample of people with first-episode psychosis (FEP).

In 13 articles, the relationship between premorbid adjustment and social cognition was not the main aim of the study. However, 10 studies explored this question as the main objective7,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34.

General social cognition and premorbid adjustment

A total of five studies considered social cognition as a global construct, using three different assessments: a general scale to measure social cognition in psychosis (GEOPTE)35, the Mayer-Salovey Emotional Intelligence Test, MSCEIT36, and a social cognition index obtained from the Facial Emotion Identification Test (FEIT)37 and The Awareness of Social Inference Test (TASIT)38 scores.

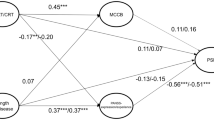

In a cross-sectional study on schizophrenia, Bucci et al.28 found that individuals with poorer premorbid adjustment (specifically in academic PAS) exhibited lower scores in social cognition (r = −0.19; p < 0.0001), as assessed by FEIT (emotional recognition) and the TASIT (Theory of Mind). Additionally, two separate cross-sectional studies analyzed social cognition (using GEOPTE) and premorbid adjustment (using PAS) as predictors of remission in individuals with schizophrenia (San et al.39 and Bobes et al.40). It should be highlighted that the primary aim of these manuscripts was not to assess the relationship between social cognition and premorbid adjustment. However, they found that both constructs independently contribute to predicting remission.

Two other cross-sectional studies examined social cognition, using the MSCEIT in samples of FEP, founding a relationship between both concepts. Casado-Ortega et al.33 found a positive correlation between premorbid IQ and social cognition (r = 0.406; p = 0.004) and Bridgwater et al.34 described that premorbid maladjustment in childhood was correlated with deficits in emotion processing (r = 0.397; p = 0.011).

Theory of mind and premorbid adjustment

Considering all the subcomponents of social cognition, Theory of Mind is the most highly related to premorbid adjustment, having a total of 13 articles. Most of them, 11 found significant associations between premorbid adjustment and Theory of Mind. One study did not find any association between premorbid IQ and Theory of Mind41 in acute in-patients with schizophrenia. Another study found that Theory of Mind and premorbid adjustment explain higher likelihood of suicidality42 in patients with schizophrenia, but the authors did not explore the relationship between both concepts directly.

Regarding those articles that found a relationship between premorbid adjustment and Theory of Mind all are based on samples of schizophrenia patients. Duñó et al.30 in a cross-sectional study found a tendency to worse performance in first-order tasks of Theory of Mind in early adolescence (χ2 = 5.35; p = 0.069) and late adolescence (χ2 = 6.64; p = 0.073) premorbid periods and second-order tasks of Theory of Mind in early adolescence (χ2 = 5.6; p = 0.061) and late adolescence (χ2 = 4.69; p = 0.096). Furthermore, Duñó et al.31 in a cross-sectional study found that lower scores in first-order (B = −1.990; CI: −3.754, −0.0227; p = 0.027) and second-order (B = −14.003; CI: −26.340, −1.666; p = 0.026) tasks of Theory of Mind were associated with worse social premorbid adjustment from infancy through adolescence. A cross-sectional study43 reported that participants with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and autistic traits manifested worse premorbid adjustment than people with schizophrenia without autistic traits, especially during childhood (F = 7.584; p = 0.007) and early adolescence (F = 7.338; p = 0.008). A previous study by the same authors27 based on a cross-sectional study reported that people with schizophrenia with poorer premorbid adjustment presented more impairment in Theory of Mind than those with better premorbid adjustment. Similarly, Buonocore et al.29 in a before and after study found that people with schizophrenia with high early premorbid adjustment and IQ within normal limits had significantly better performance in tasks of Theory of Mind than those who had either worse premorbid adjustment and mild intellectual impairments or average/high premorbid adjustment but moderate intellectual impairment (X2 = 9.57; p = <0.001). In this line, Schenkel et al.25 in a cross-sectional study found that poorer performance on Theory of Mind, measured by the Hinting Task, was associated with poor premorbid social functioning (t(40) = 3.86; p < 0.0001) in people with schizophrenia.

A significant interaction between Theory of Mind and premorbid IQ was described in five articles. Piovan et al.44, in a cross-sectional study, found that in outpatients diagnosed with schizophrenia, premorbid general intelligence significantly correlated with the affective but not with the cognitive Theory of Mind subcomponent (r = 0.553; p = 0.002). Abdel-Hamid et al.45, in a cross-sectional study, found a significant interaction between Theory of Mind and premorbid IQ (r = 0.377, p = 0.007) in people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Using a similar sample, Marsh et al.46 using a cross-sectional study found similar results, showing that improvement on the Picture Sequencing Test for False Belief (PST-FB) (r = 0.599; p = 0.024) and on the Picture Sequencing Test for Mechanical Control (PST-MC) (r = −0.751; p = 0.002) were associated with premorbid IQ. In the same line Deste et al.47 described that, in people with schizophrenia, a higher premorbid IQ predicted a better mental state attribution (Theory of Mind) performance, as measured by the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (Model F = 87.362, R2 = 0.434, p < 0.001), and TASIT (Model F = 43.784, R2 = 0.340, p < 0.001). Regarding the relationship between Theory of Mind and premorbid IQ in FEP, Uren et al.48, in a cross-sectional study, described that this domain is the only one that discriminates between clusters based on premorbid IQ adjustment (p = 0.009).

Another important construct related to Theory of Mind is mentalization or metacognition32, operationalized as reflective functioning and the ability of the individual to understand and infer mental states of both themselves and others49. One cross-sectional study analyzed the associations between social and cognitive premorbid adjustment, and the individuals’ reflective functioning49 in people with FEP, but they did not find significant results. Two other cross-sectional studies assessed metacognition with contradictory results32,50. One of them did not find significant associations between premorbid adjustment and the subscales of Awareness of the Mind of the Other50. However, MacBeth et al.32, using a modified version of the Metacognition Assessment Scale (MAS-R)51 found a significant association between poor early adolescent premorbid adjustment and poor Understanding of the other’s Mind (r = −00; p = 0.03).

Emotional recognition (or emotional processing) and premorbid adjustment

Four studies assess emotional recognition and premorbid adjustment in samples of people with schizophrenia.

Only two studies directly investigated the relationship between emotion recognition and premorbid adjustment7 and premorbid IQ in people with schizophrenia47. The first one, Dewangan et al.7, in a cross-sectional study, found that poor social premorbid adjustment predicts poor recognition of negative emotions (B = −0.315; p < 0.001). The second one, Deste et al.47, found that a higher premorbid IQ predicted a better emotion processing performance, as measured by the Penn Emotion Recognition Test (ER-40) (Model F = 27.031, R2 = 0.241, p < 0.001), and as measured by the Bell Lysaker Emotion Recognition Task (BLERT) (Model F = 70.269, R2 = 0.381, p < 0.001).

Conversely, Marsh et al.46, found that, although improvements in Theory of Mind correlated with premorbid IQ, emotion recognition did not improve after a social cognitive training program in a sample of people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Similarly, Gopalakrishnan et al.26, in a cross-sectional study, reported that in people with schizophrenia, premorbid adjustment but not facial emotion recognition is related to poor socio-occupational functioning.

Other components of Social cognition: Attributional Style and Social Perception or Social Knowledge.

Two studies have analyzed the relationship between premorbid adjustment and attributional bias and social perception/social knowledge. Only the cross-sectional study of Dewangan et al.7 analyzed the relationship between social perception/social knowledge with premorbid adjustment in people with paranoid schizophrenia. The authors found that premorbid poor cognitive performance predicts poor social knowledge (β = –0.259, p = 0.006). The relationship between premorbid adjustment (using premorbid IQ) and attributional bias was analyzed only in one cross-sectional study41, finding no relationship between both constructs in a sample of people with schizophrenia7.

Risk of bias

Regarding the risk of bias, most of the studies included in the review (17 articles) were scored as good. Only 6 studies were classified as “fair”, suggesting some methodological limitations7,26,32,42,43,48. Information about the items’ scores is provided in Table 2.

Discussion

We have reviewed literature assessing the relationship between premorbid adjustment and social cognition. A large proportion of the evidence collected in this review shows a significant relationship between these two constructs, specifically between Theory of Mind and premorbid adjustment. In this sense, the lack of an adequate development of cognitive and social premorbid performances, especially in the early stages of the life cycle, has been related to difficulties in processes and functions that allow people to understand the interpersonal world once the onset of psychosis occurs. This evidence involves clinical and research implications. On the one hand, it provides evidence of the need for preventive intervention programs in school stages, focused on improving social and cognitive skills. On the other hand, these results require more research to determine the causality of the relationships found. The results obtained are interpreted below, showing the clinical and research implications derived from each of the components of social cognition analyzed.

Few studies have observed no relationships between social cognition and premorbid adjustment, suggesting that the relationship between these constructs is quite common. In fact, the lowest scores in the risk of bias (scored as “fair”) were obtained in two of the studies that did not find an association between premorbid adjustment and social cognition26,42. In the same way, there are two studies39,40, that did not provide information regarding a possible relationship between social cognition and premorbid adjustment. Additionally, they evaluate social cognition with a general measure (GEOPTE scale), which does not make the results comparable with studies analyzing social cognition by components. Social cognition is not a unitary construct, including several domains that should be assessed separately.

Considering Theory of Mind and premorbid adjustment, Duñó et al.31 found that, in patients with schizophrenia, second-order Theory of Mind tasks were more discriminative than first-order ones in relation to poor premorbid adjustment across different age periods, indicating that second-order Theory of Mind tasks may be more suited to assess mentalistic abilities. Possibly, second-order Theory of Mind tasks are more cognitively demanding, and their deficit may already be indirectly reflected as poor premorbid adjustment in earlier development periods. In fact, Healey et al.52 suggested that the decline in Theory of Mind occurs in the reverse order of which the abilities were acquired. In this line, people with lower scores in first and second-order Theory of Mind tasks tended to present worse social premorbid adjustment in infancy and adolescence. This suggests that deficits in Theory of Mind may be trait-like features of people with poor premorbid adjustment who will develop psychosis18. This fact can also be supported by studies showing a significant positive interaction between Theory of Mind and premorbid IQ44,45,46,47,48. However, further studies will be needed to determine the causality of this relationship. Besides, some of the studies that have reported results in line with relating both constructs present low methodological quality25,27,48.

Regarding the relationship between premorbid adjustment and mentalization, a study noted a significant association with poor early adolescent social premorbid adjustment and poor Understanding of the other’s Mind32. These metacognitive difficulties may reflect psychodevelopmental factors. As suggested by Peterson & Wellman53, early adolescence may be a period of maximum demand in terms of social experiences, and of maximum development of Theory of Mind abilities. However, alternative hypotheses, such as the one held by Tierney & Nelson54, suggested an explanation based on “experience-dependent plasticity”: there is no one period that is more sensitive to relevant experience for the development of Theory of Mind, it is feasible at any age, providing the necessary stimulating experiences. In this sense, the possibility of intervening as soon as possible is left open to offer experiences that stimulate Theory of Mind capacity53, specifically in individuals with premorbid social and cognitive difficulties. More research is required to expand the evidence and to elucidate the relationship between premorbid adjustment and mentalization, considering that the only study found in this review has methodological limitations.

Emotional processing is another component of social cognition that may already be affected in the premorbid phase of psychotic disorders. The scarce evidence has shown the predictive character of premorbid sociability and cognitive performance in relation to the severity of positive symptoms, social knowledge and deficit in negative emotion recognition in schizophrenia7. People with poor premorbid adjustment may have been less exposed to social interactions, diminishing their opportunities to identify and discriminate facial and vocal emotions, and to manage their own emotions. Consequently, a lack of social experience may result in inadequate development of emotion processing, even before the onset of the disorder. A previous study46 has shown a lack of effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in emotion recognition in patients with schizophrenia, perhaps due to a deficit in social functioning that should be established beforehand. However, this hypothesis needs more evidence to be confirmed, as well as higher quality studies since some of the limited evidence found presents methodological limitations, such as the study of Dewangan & Singh7.

In addition, social knowledge has also been related to premorbid adjustment in patients with schizophrenia, although the evidence is scarce and shows low methodological quality7. We hypothesize that social perception/knowledge may be an implicit construct in the academic environment. Consequently, good cognitive performance could facilitate learning social rules and increase opportunities for social experiences. Therefore, it could be feasible to improve areas associated with social perception, such as social skills, community functioning, and social problem-solving15,55. Likely, social perception has been less studied because of the limited number of measures, the complexity of the construct, and the difficulty in isolating it from other social cognition domains, such as Theory of Mind14.

Frequently, individuals with persecutory delusions attribute negative outcomes to others, rather than to situations. This is known as a personalizing bias56. There seems to be no association between personalizing bias and premorbid IQ, as reported by Berry et al.41. Although there is an association referred to the morbid phase, between attributional style and cognitive aspects such as IQ57 or cognitive flexibility58. Nevertheless, data on premorbid adaption and how individuals explain the causes of events are limited to draw solid conclusions. It is described that poor cognitive premorbid adjustment is neurodevelopmentally determined in people with schizophrenia and with stable impairment over time. Therefore, it would be interesting to know whether a poorer cognitive premorbid adjustment is related to a maladjusted attributional style59. Furthermore, attributional biases should also be interpreted in relation to social premorbid adjustment. Less social competence during the premorbid phase of the disorder may reflect attributional biases that lead to conflicting social experiences. In contrast to this hypothesis, Garety and Freeman60 suggested that attributional style may more closely resemble a thinking style associated with personality rather than a performance-based social cognitive skill.

In this review, various overlapping constructs have been mentioned49,50. These refer to the ideas that people form about themselves and others and include social cognition, mentalization, and metacognition. Both constructs, mentalization and metacognition, are confused and could be interchangeable in some studies61. However, this review aims to overcome this limitation that some studies have indicated, showing the nuances of each of these constructs: metacognition is a broad concept that refers to the dynamic process of integrating the information obtained through recognition and understanding of one’s own and others’ cognitive processes. Mentalization is closer to metacognition because it is not a static capacity but rather one that changes within inter and intrapersonal contexts62. Both concepts refer to the ability to understand one’s own cognitive processes and those of others, and not so much in the content of thought, but the concept of mentalization is restricted to the context of attachment relationships. However, social cognition is a more specific term because it is focused on the accuracy of how social events are interpreted, which is a static assessment63. Social cognition encompasses 4 domains: emotion processing; social perception, Theory of Mind and attributional style. We have included these two terms, mentalization and metacognition, when they were related to Theory of Mind. In short, more scientific evidence that contemplates this conception of the terms and allows obtaining results that can be interpreted in an integral way is needed.

Given the importance of premorbid adjustment and social cognition, and the significant relationship between these two variables, it seems that a thorough assessment of premorbid adjustment could be beneficial to tailor personalized interventions and preventive strategies to improve the prognosis of psychosis. Currently, the existing evidence on the efficacy of early intervention programs aimed at people with an incipient psychotic disorder is well-known. These types of interventions include strategies to improve access to mental health care, as well as comprehensive evaluation and intervention strategies that make it possible to adjust to the needs of each patient and thus improve the course of the disorder, even avoiding its appearance.

Early psychological interventions, such as metacognitive training addressed to improve social cognition, should be delivered specially in those people with worse premorbid adjustment. Metacognitive training, which is addressed to increase self-reflection on thought processes and sowing doubts in patients about their non-adaptive beliefs, has shown their effectiveness regarding some components of social cognition such as Theory of Mind and attributional style in patients with recent-onset psychosis64. Furthermore, it is possible that deficits in social cognition already appear in the phases prior to the onset of FEP. In this sense, disturbances of social cognition have been considered by some authors as a possible trait marker of schizophrenia18. Social cognitive impairments would have trait-like qualities that precede the onset of the disorder and are candidate endophenotypes for schizophrenia17,19,20,21,22. These impairments could be already present in the premorbid phase and be manifested subtly, in the form of poorer premorbid adjustment. In this sense, social cognition may be considered as a vulnerability marker for psychosis to be contemplated in psychosis detection algorithms to reduce false positive identification. A review article22 on social cognition in the ultra-high-risk population concluded that deficits in certain social cognitive abilities appear to be present.

We found some limitations while working on this review, for example, that most of the retrieved literature focused on only two components of social cognition: Theory of Mind and emotion recognition. One of the reasons for it is the availability of assessment instruments. However, it should be noted that there was a great variability among the included articles in instruments to measure both constructs. Likewise, there was considerable diversity in the assessment of premorbid adjustment using different instruments (PAS or medical chart reviews25, and Brief Intelligence Test44 or NART41, among others, respectively), with the PAS6,65,66, being the most complete instrument used. Besides, some studies analyzed premorbid adjustment considering social and cognitive domains. Others assess premorbid adjustment only considering premorbid IQ. This variability in the measurement instruments may be behind the lack of consensus in some studies that do not find a relationship between social cognition and premorbid adjustment. Another explanation for the lack of consensus in some studies could be due to the retrospective nature of the premorbid adjustment variable. A high percentage of patients with psychotic disorders have cognitive impairment, including memory difficulties. This can make it difficult to remember information that occurred in previous phases to the onset of the disease. Finally, another limitation is that we did not include the concept of “cognitive reserve” in the search terms, as an umbrella term for premorbid adjustment, but this term was not included because it can refer to cognitive domains before and after the onset of schizophrenia. In the same vein, we have not included in the search MESH terms; however, we have included those relevant words related to our aim.

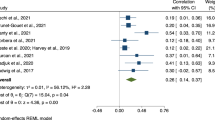

In the light of the results of this review, we make the following recommendations for future studies: a) The assessment of social cognition and premorbid adjustment should be consensual to reduce heterogeneity factors that may hinder comparability of results across studies. In this sense, regarding social cognition, we recommend assessing specifically the subcomponents rather than the global construct, placing greater emphasis on the study of the domains of social perception and attributional style. With regard to premorbid adjustment, the most widely used scale has been the PAS that allows the assessment of premorbid adjustment across the life cycle and by sub-components. The PAS scale is an objective instrument and measures broader concepts than premorbid IQ, but we recommend not using the general subscale of the PAS for this purpose, as some items assess aspects related to the morbid phase66; b) According to a previous study8 supporting the idea of considering the premorbid adjustment as a broad concept that encompasses not only social and cognitive aspects, other areas of the person’s life, such as family, vocation, personal well-being, interests in life, energy levels, economic independence and also those related to the way social information is processed, should be taken into account when clinical professionals are exploring the premorbid phase. In this sense, social cognition aspects should also be assessed in the premorbid phase of psychosis, among others; c) Due to the heterogeneity of the assessment methods used in the studies comprising this review, it has not been possible to perform a meta-analysis. In the future, it will be necessary to meta-analyze the influence of premorbid adjustment on the mental processes behind social interactions; and finally, d) In order to improve the quality of the information collected about the premorbid phase, more studies should be carried out focusing on people in a high-risk state of psychosis. In addition, a greater number of prospective and longitudinal studies should be carried out in the future, which would have their starting point in the prodromal phase, making way for causality.

Conclusions

This comprehensive review reveals a noteworthy connection between certain domains of social cognition, particularly Theory of Mind, and premorbid adjustment. However, there is a need for additional research to explore the relationships involving social perception/knowledge and attributional style. It is crucial to emphasize that longitudinal studies focusing on the early phases of psychosis, before its onset, would provide valuable insights. There is a suggestion to examine functioning in premorbid phases, considering not only social and cognitive functioning but also in terms of social cognition.

The findings indicate that interventions such as metacognitive training should be considered in the individualized therapeutic plans for patients with psychotic disorders who have experienced an impoverished premorbid phase. It is also recommended that future studies address and meta-analyze the influence of premorbid adjustment on social cognition.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

References

McFarlane, W. R. et al. Clinical and Functional Outcomes After 2 Years in the Early Detection and Intervention for the Prevention of Psychosis Multisite Effectiveness Trial. Schizophr. Bull. 41, 30–43 (2015).

Carruthers, S. P., Van Rheenen, T. E., Gurvich, C., Sumner, P. J. & Rossell, S. L. Characterising the structure of cognitive heterogeneity in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 107, 252–278 (2019).

Díaz-Caneja, C. M. et al. Predictors of outcome in early-onset psychosis: A systematic review. npj Schizophr 1, 1–10 (2015).

Strauss, J. S., Kokes, R. F., Klorman, R. & Sacksteder, J. L. Premorbid adjustment in schizophrenia: concepts, measures, and implications. I. The concept of premorbid adjustment. Schizophr. Bull. 3, 182–185 (1977).

Addington, J. & Addington, D. Patterns of premorbid functioning in first episode psychosis: Relationship to 2-year outcome. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 112, 40–46 (2005).

Cannon-Spoor, H. E., Potkin, S. G. & Wyatt, R. J. Measurement of Premorbid Adjustment in Chronic Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 8, 470–484 (1982).

Dewangan, R. L. & Singh, P. Premorbid adjustment in predicting symptom severity and social cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. East Asian Arch. Psychiatry 28, 75–79 (2018).

Barajas, A. et al. Three-factor model of premorbid adjustment in a sample with chronic schizophrenia and first-episode psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 151, 252–258 (2013).

Monte, R. C., Goulding, S. M. & Compton, M. T. Premorbid functioning of patients with first-episode nonaffective psychosis: A comparison of deterioration in academic and social performance, and clinical correlates of Premorbid Adjustment Scale scores. Schizophr. Res. 104, 206–213 (2008).

Strauss, G. P. et al. Differential patterns of premorbid social and academic deterioration in deficit and nondeficit schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 135, 134–138 (2012).

Kern, R. S. & Horan, W. P. Definition and measurement of neurocognition and social cognition in Neurocognition and Social Cognition in Schizophrenia Patients: Basic Concepts and Treatment, 177, V. Roder & A. Medalia, Eds. Karger, 2010, 1–22.

Nuechterlein, K. H. et al. Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 72, 29–39 (2004).

Green, M. F. et al. Social cognition in schizophrenia: An NIMH workshop on definitions, assessment, and research opportunities,”. Schizophr. Bull. 34, 1211–1220 (2008).

Pinkham, A. E. et al. The social cognition psychometric evaluation study: Results of the expert survey and RAND Panel. Schizophr. Bull. 40, 813–823 (2014).

Couture, S. M., Penn, D. L. & Roberts, D. L. “The functional significance of social cognition in schizophrenia: A review,”. Schizophr. Bull. 32, 44–63 (2006).

M. J. Page et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews BMJ, n71, (2021).

Green, M. F., Horan, W. P. & Lee, J. Social cognition in schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 620–631 (2015).

Sprong, M., Schothorst, P., Vos, E., Hox, J. & Van Engeland, H. Theory of Mind in schizophrenia: Meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 191, 5–13 (2007).

Van Donkersgoed, R. J. M., Wunderink, L., Nieboer, R., Aleman, A. & Pijnenborg, G. H. M. Social cognition in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis: A meta-analysis. PLoS One 10, 1–16 (2015).

Glenthøj, L. B. et al. “Social cognition in patients at ultra-high risk for psychosis: What is the relation to social skills and functioning?,”. Schizophr. Res. Cogn. 5, 21–27 (2016).

Kim, H. S. et al. Processing of facial configuration in individuals at ultra-high risk for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 118, 81–87 (2010).

Thompson, A. D., Bartholomeusz, C. & Yung, A. R. Social cognition deficits and the ‘ultra high risk’ for psychosis population: A review of literature. Early Interv. Psychiatry 5, 192–202 (2011).

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Study Quality Assessment Tools (2021).

García-Mieres, H., Niño-Robles, N., Ochoa, S. & Feixas, G. Exploring identity and personal meanings in psychosis using the repertory grid technique: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 26, 717–733 (2019).

Schenkel, L. S., Spaulding, W. D. & Silverstein, S. M. Poor premorbid social functioning and Theory of Mind deficit in schizophrenia: Evidence of reduced context processing?. J. Psychiatr. Res. 39, 499–508 (2005).

Gopalakrishnan, R., Behere, R. & Sharma, P. Factors affecting well-being and socio-occupational functioning in schizophrenia patients following an acute exacerbation: A hospital based observational study. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 37, 423–428 (2015).

Bechi, M. et al. The Influence of Premorbid Adjustment and Autistic Traits on Social Cognitive Dysfunction in Schizophrenia. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 26, 276–285 (2020).

Bucci, P. et al. Premorbid academic and social functioning in patients with schizophrenia and its associations with negative symptoms and cognition. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 138, 253–266 (2018).

Buonocore, M. et al. Cognitive reserve profiles in chronic schizophrenia: Effects on Theory of Mind performance and improvement after training. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 24, 563–571 (2018).

Duñó Ambròs, R. et al. Ajuste premórbido pobre vinculado al deterioro en habilidades de teoría de la mente: estudio en pacientes esquizofrénicos estabilizados. Rev. Neurol. 47, 242 (2008).

Duñó, R. et al. Poor premorbid adjustment and dysfunctional executive abilities predict Theory of Mind deficits in stabilized schizophrenic outpatients. Clin. Schizophr. Relat. Psychoses 2, 205–216 (2008).

Macbeth, A. et al. Metacognition, symptoms and premorbid functioning in a First Episode Psychosis sample. Compr. Psychiatry 55, 268–273 (2014).

A. Casado-Ortega et al. Social cognition and its relationship with sociodemographic, clinical, and psychosocial variables in first-episode psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 302, (2021).

Bridgwater, M. A., Horton, L. E. & Haas, G. L. Premorbid adjustment in childhood is associated with later emotion management in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 240, 233–238 (2022).

Sanjuan, J. et al. “[GEOPTE Scale of social cognition for psychosis].,”. Actas Esp. Psiquiatr. 31, 120–128 (2003).

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., Caruso, D. R. & Sitarenios, G. Measuring emotional intelligence with the MSCEIT V2.0. Emotion 3, 97–105 (2003).

Kerr, S. L. & Neale, J. M. Emotion Perception in Schizophrenia: Specific Deficit or Further Evidence of Generalized Poor Performance?. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 102, 312–318 (1993).

McDonald, S. et al. Reliability and validity of The Awareness of Social Inference Test (TASIT): A clinical test of social perception. Disabil. Rehabil. 28, 1529–1542 (2006).

San, L., Ciudad, A., Álvarez, E., Bobes, J. & Gilaberte, I. Symptomatic remission and social/vocational functioning in outpatients with schizophrenia: Prevalence and associations in a cross-sectional study. Eur. Psychiatry 22, 490–498 (2007).

Bobes, J. et al. Recovery from schizophrenia: Results from a 1-year follow-up observational study of patients in symptomatic remission. Schizophr. Res. 115, 58–66 (2009).

Berry, K., Bucci, S., Kinderman, P., Emsley, R. & Corcoran, R. An investigation of attributional style, Theory of Mind and executive functioning in acute paranoia and remission. Psychiatry Res 226, 84–90 (2015).

Duñó, R. et al. Suicidality connected with mentalizing anomalies in schizophrenia: A study with stabilized outpatients. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1167, 207–211 (2009).

Bechi, M. et al. The association of autistic traits with Theory of Mind and its training efficacy in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. Cogn. 19, 100164 (2020).

Piovan, C., Gava, L. & Campeol, M. Theory of Mind and social functioning in schizophrenia: Correlation with figurative language abnormalities, clinical symptoms and general intelligence. Riv. Psichiatr. 51, 20–29 (2016).

Abdel-Hamid, M. et al. Theory of Mind in schizophrenia: The role of clinical symptomatology and neurocognition in understanding other people’s thoughts and intentions. Psychiatry Res. 165, 19–26 (2009).

Marsh, P. et al. An open clinical trial assessing a novel training program for social cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Australas. Psychiatry 21, 122–126 (2013).

Deste, G. et al. Autistic symptoms predict social cognitive performance in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 215, 113–119 (2020).

Uren, J., Cotton, S. M., Killackey, E., Saling, M. M. & Allott, K. Cognitive clusters in first-episode psychosis: Overlap with healthy controls and relationship to concurrent and prospective symptoms and functioning. Neuropsychology 31, 787–797 (2017).

MacBeth, A., Gumley, A., Schwannauer, M. & Fisher, R. Attachment states of mind, mentalization, and their correlates in a first-episode psychosis sample. Psychol. Psychother. Theory, Res. Pract. 84, 42–57 (2011).

Trauelsen, A. M. et al. Metacognition in first-episode psychosis and its association with positive and negative symptom profiles. Psychiatry Res 238, 14–23 (2016).

MacBeth, A. et al. Metacognition in First Episode Psychosis: Item Level Analysis of Associations with Symptoms and Engagement. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 23, 329–339 (2016).

Healey, K. M., Bartholomeusz, C. F. & Penn, D. L. “Deficits in social cognition in first episode psychosis: A review of the literature,”. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 50, 108–137 (2016).

Peterson, C. C. & Wellman, H. M. Longitudinal Theory of Mind (ToM) Development From Preschool to Adolescence With and Without ToM Delay. Child Dev 90, 1917–1934 (2019).

Tierney, A. L. & Nelson, C. A. Brain Development and the Role of Experience in the Early Years. Zero Three 30, 9–13 (2009).

Fett, A. K. J. et al. The relationship between neurocognition and social cognition with functional outcomes in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 35, 573–588 (2011).

Garety, P. A. & Freeman, D. Cognitive approaches to delusions: A critical review of theories and evidence. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 38, 113–154 (1999).

Bliksted, V., Fagerlund, B., Weed, E., Frith, C. & Videbech, P. Social cognition and neurocognitive deficits in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 153, 9–17 (2014).

Stange, J. P. et al. Extreme attributions predict transition from depression to mania orhypomania in bipolar disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 47, 1329–1336 (2013).

McGlashan, T. H. & Hoffman, R. E. Schizophrenia as a disorder of developmentally reduced synaptic connectivity. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 57, 637–648 (2000).

Garety, P. A. & Freeman, D. The past and future of delusions research: From the inexplicable to the treatable. Br. J. Psychiatry 203, 327–333 (2013).

L. Díaz-Cutraro et al. Metacognition in psychosis: What and how do we assess it?. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2022.

Bateman, A. & Fonagy, P. Mentalization-based treatment. Psychoanal. Inq. 33, 595–613 (2013).

P. H. Lysaker et al. Metacognitive function and fragmentation in schizophrenia: Relationship to cognition, self-experience and developing treatments. Schizophr. Res. Cogn. 19 (2020).

Ochoa, S. et al. Randomized control trial to assess the efficacy of metacognitive training compared with a psycho-educational group in people with a recent-onset psychosis. Psychol. Med. 47, 1573–1584 (2017).

Barajas, A. et al. Spanish validation of the Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS-S). Compr. Psychiatry 54, 187–194 (2013).

Van Mastrigt, S. & Addington, J. Assessment of premorbid function in first-episode schizophrenia: Modifications to the Premorbid Adjustment Scale. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 27, 92–101 (2002).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Spanish Government), research grant number PI18/00212, (Co-funded by European Regional Development Fund/European Social Fund “A way to make Europe”/“Investing in your future”), and Generalitat de Catalunya, Health Department, PERIS call (SLT006/17/00231). In addition, this manuscript has been elaborated with the support of the Ministry of Research and Universities of the Government of Catalonia to the Research Group COGen-MH “Cognition and Gender: Implications for Mental Health” (Code: 2021 SGR 000534).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Punsoda-Puche, P., Barajas, A., Mamano-Grande, M. et al. Relationship between social cognition and premorbid adjustment in psychosis: a systematic review. Schizophr 10, 36 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-023-00428-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-023-00428-y