Abstract

We report two malignant sacrococcygeal tumors in infants that were associated with pathogenic DICER1 variation. These tumors were composed of primitive neuroepithelium, embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, and cartilage and initially diagnosed as immature teratomas. One child developed intracranial metastasis and died. The second child underwent surgery and chemotherapy and achieved complete remission. This child subsequently developed five additional DICER1-associated neoplasms by age nine. Genetic analysis revealed that both tumors harbored biallelic pathogenic DICER1 variation. We believe these cases represent another novel subtype of DICER1-associated tumor. This new entity, which we propose to call DICER1-associated presacral malignant teratoid neoplasm, may be difficult initially to distinguish from immature teratoma, but recognizing it as an entity can prompt appropriate classification as an aggressive malignancy and facilitate appropriate genetic counseling, DICER1 germline variant testing, screening, and education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

DICER1 encodes an RNase III endonuclease and plays a pivotal role in miRNA processing [1]. Since it was first reported as the causative gene for familial pleuropulmonary blastoma, pathogenic DICER1 germline variation has been identified in a number of tumor types of seemingly diverse histogenesis including pleuropulmonary blastoma, ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor, cystic nephroma and pituitary blastoma and some non-cancerous conditions, including multinodular goiter and macrocephaly [2,3,4,5,6]. DICER1-associated tumors typically harbor biallelic DICER1 variation: a loss-of-function variant (usually germline) and a somatic “hotspot” variant within the RNase IIIb domain (E1705, D1709, G1809, D1810, or E1813). Here, we report two infants who had pathologically unique presacral tumors that harbored biallelic DICER1 variants. We would propose that these neoplasms with their collage of dysembryonic tissue patterns, initially interpreted as immature teratomas, represent another unique DICER1-related tumor. However, the various pathologic representatives in these neoplasms overlapped to a considerable degree with the other DICER1-related dysontogenetic neoplasms with their own teratoid morphologic attributes.

Material and methods

Human subjects review

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at all participating institutions. Patient 1 was enrolled in the Japanese Children’s Cancer Group observational study. Patient 2 was enrolled in the National Cancer Institute Natural History of DICER1 Syndrome study (NCT-01257597). Eligibility criteria included a history of a DICER1-associated neoplasm or documentation of a pathogenic germline DICER1 variant. Informed, written consent was obtained from the patients’ parents.

DICER1 genetic analyses

For the tumor from patient 1, targeted sequencing for all coding exons from 93 genes (Supplemental Table 1) was performed on an Ion Proton Sequencer (Life Technologies). Reads were mapped onto the hg19 human reference genome sequence and common variation from dbSNP build (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/), the 1000 Genomes database (http://www.1000genomes.org), and Human Genetic Variation Database (http://www.hgvd.genome.med.kyoto-u.ac.jp/) was excluded. In Patient 2, germline DICER1 testing was performed by Invitae on DNA extracted from blood. Somatic DICER1 sequencing of the tumor performed on DNA extracted from the paraffin block was performed as previously described [7].

Results

Patient 1

A 1-week-old boy was admitted because of loss of lower extremity movement. His prenatal period and family history were unremarkable. Magnetic resonance imaging showed an extradural tumor within the spinal canal extending from L2 to the sacral region (Fig. 1a, b). The levels of serum alpha-fetoprotein and β-human chorionic gonadotropin were within the normal ranges for his age. Following the partial resection of a hemorrhagic mass, the patient received one course of chemotherapy with etoposide and carboplatin and subsequently underwent gross total resection. Pathologic examination of the resected masses revealed a multipatterned neoplasm composed of primitive neuroepithelial and mesenchymal elements. The neuroepithelial components consisted of primitive neuronal cells forming occasional true rosettes with a resemblance to medulloepithelioma (Fig. 2a, b). There were scattered nodules of primitive cartilage rimmed by spindle cells (Fig. 2c). The remainder of the tumor was composed of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma showing a full range of differentiation from blastema to maturing skeletal muscle (Fig. 2d). Neither epithelial-lined cysts, cutaneous structures, or fetal-appearing tissues like liver or pancreas nor malignant germ-cell elements like endodermal sinus tumor (yolk sac tumor) were identified.

Radiological findings, with arrow indicating tumor. Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging at first diagnosis (a, b), the first relapse (c), and the second relapse after radiotherapy (d, e) in Patient 1. Patient 2 axial (f) and coronal (g) views from pre-operative computed axial tomography imaging with oral and intravenous contrast showing a heterogenous, paramedian pelvic mass and asymmetric kidneys. There is delayed urinary excretion on the right due to obstruction from the mass. In the axial image (f), the balloon of the urinary catheter is apparent and displaced ventrally and significantly away from the midline

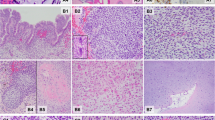

Microscopic appearance of the multipatterned tumor from Patient 1. The primary tumor from Patient 1 showed immature neuroepithelial components including multilayered rosettes and medulloepithelioma-like component (a, b), and immature mesenchymal tissues, including mature cartilage and skeletal muscle cells (c, d). The recurrent tumor was composed predominantly of neuroepithelial tubular structures in loose mesenchymal tissue (e). These tubules were positive for cytokeratin CAM 5.2 (f). Hematoxylin and eosin (a–e); Anti-CAM 5.2 (f): Original magnification ×100 (a); ×200 (c, e, f), and ×400 (b, d)

The patient received no postoperative chemotherapy, but eight months later, the tumor recurred and had extended to thoracic level 9 (Fig. 1c). The patient underwent partial resection followed by local radiation (45 Gy) and chemotherapy. Although the tumor responded transiently to the salvage therapy, it recurred outside the irradiation field (Th3/Th4) and metastasized to the midbrain (Fig. 1d, e). The patient died of the disease 25 months after the initial diagnosis.

The recurrent tumor consisted of neuroepithelial tubular structures and loose mesenchymal tissue (Fig. 2e). Cytokeratin CAM5.2 was positive in the neuroepithelial tubules (Fig. 2f).

Patient 2

A 4-month-old girl with an unremarkable prenatal and a limited family history presented with abdominal distention, poor feeding, and blood in her diaper. Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography scans showed a heterogeneous 6.5 × 6.5 × 5.0 cm mass within the pelvis and associated high-grade obstruction of the right kidney with bilateral hydronephrosis, right greater than left (Fig. 1f, g). Spine magnetic resonance imaging showed a large presacral mass with heterogenous contrast enhancement. She underwent resection of the pelvic/presacral mass.

Pathologically, the tumor was composed predominantly of immature neuroepithelium in epithelial cords (Fig. 3a), clusters of neuroblasts with rare true rosettes (Fig. 3b), and differentiating neurocytic areas in a neuropil background (Fig. 3c). Rare immature cartilage nodules were seen (Fig. 3d). Embryonal rhabdomyo sarcomatous areas with skeletal muscle differentiation were also present (Fig. 3e, f). Neither endodermal sinus tumor nor other germ-cell patterns were identified.

Microscopic appearance of the multipatterned tumor from Patient 2. The tumor from Patient 2 was composed predominantly of immature neuroepithelium in epithelial cords (a), clusters with neuroblasts with rare true rosettes (b) and differentiating neurocytic areas in a neuropil background (c). Rare immature cartilage nodules were seen (d). Embryonal rhabdomyosarcomatous areas with skeletal muscle differentiation were also present (e, f). Hematoxylin and eosin: Original magnification ×200 (a, d, e); ×100 (c), and ×400 (b, f)

She was treated with chemotherapy and two tandem auto stem cell transplantations. Subsequently she developed a vaginal embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (age 5 years), sarcoma of the right kidney arising in a cystic nephroma (age 8 years), papillary thyroid microcarcinoma and nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma (age 8 years) and cystic nephroma of the left kidney (age 9 years).

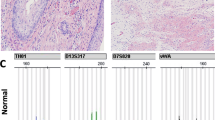

DICER1 sequencing

In Patient 1, two nonsynonymous variants in DICER1 (c.2233 C > T, p.Arg745* and c.5437 G > A, p.Glu1813Lys) were detected, with a variant allelic frequency (VAF) of 52.3% and 34.2%, respectively. No other nonsynonymous variation in other genes on the panel was detected. These results were established after the patient’s death and germline or family testing was not performed.

Patient 2 underwent germline DICER1 testing at age 8 years. Sequence results showed a pathogenic frameshift variant (c.4407_4410delTTCT, p.Ser 1470 Leufs*19); this variant was also harbored by the patient’s father, who has an unremarkable medical history. Somatic DICER1 sequencing of the tumor performed on tissue from the paraffin block showed the germline DICER1 variant (VAF: 51%) and a DICER1 “hotspot” variant (c.5113 G > A; p.Glu1705Lys; VAF: 41.4%).

Discussion

Given the age at presentation and the sacrococcygeal location, it is not surprising that these two neoplasms were initially diagnosed as immature teratomas. However, the detection of tumor-associated pathogenic DICER1 variation in Patient 1 and the occurrence of multiple DICER1-related tumors in Patient 2 (and a germline DICER1 pathogenic variant) promoted re-consideration of the pathology in these two cases. Although primitive neuroepithelial rosettes and tubules were present in both tumors, the predominant pattern was embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma in the absence of the typical spectrum of teratomatous elements or endodermal sinus tumor, which are frequent findings in immature teratoma of the sacrococcygeum [8]. Sarcomas including rhabdomyosarcoma are known to occur in germ cell neoplasms, principally in the mediastinum and gonads, but are unknown in infantile sacrococcygeal teratomas to the best of our knowledge [9, 10]. The combination of primitive neuroepithelial tubular profiles, rhabdomyoblastic, and cartilaginous nodules in these two cases are similar to those observed in several of the other DICER1-related tumors including ciliary body medulloepithelioma and cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma [3].

The immature or sarcomatous cartilage and embryonal rhabdomyosarcomatous elements are features of pleuropulmonary blastoma types I through III. Primitive neuroepithelial structures and rhabdomyosarcoma are found in pituitary blastoma and heterologous Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor of the ovary, respectively. Neither of these two neoplasms had foci of yolk sac tumor, which are often identified as microscopic foci in immature teratomas of the sacrococcygeum. These suggest the present cases are previously unidentified pathological subtype of presacral tumor and a novel DICER1-associated tumor.

The International Pleuropulmonary Blastoma/DICER1 and Ovarian and Testicular Stromal Tumor Registries performed a search of all treating institution and central review diagnoses (search terms: germ cell tumor, teratoma, yolk sac tumor, sacrococcygeal tumor, seminoma, and germinoma) for enrolled individuals with germline DICER1 pathogenic variation. There were no centrally-reviewed cases of germ cell tumors in either Registry (706 patients from more than 500 families). As the pathological findings of present cases resembles immature teratoma, we then reviewed the published accounts of DICER1 variation in germ cell tumors. As shown in Table 1, there were numerous tumors with somatic truncating or hotspot variation in DICER1, but there were no reports of pathogenic germline DICER1 variation [4, 11,12,13,14,15,16]. In addition, the tumors with DICER1 variation typically do not include detailed pathologic descriptions, and thus we cannot verify with certainty that they are not phenotypic mimics of either known or yet uncharacterized malignant neoplasms. Taken together, we could not find evidence that germ cell tumors are associated with pathogenic germline DICER1 variation.

Importantly, to date, no reported case has suggested an association between DICER1 variation and immature teratomas or infantile presacral tumor. Also of note, Patient 2 developed subsequently four DICER1-associated neoplasms; this number of the tumors was relatively high as Brenneman et al. reported the mean and median number of lesions in children with pathogenic germline DICER1 variation as 1.8 and 2.0, respectively [7].

Furthermore, immature teratomas typically are not associated with normal AFP levels and rarely disseminate intracranially, unlike the clinical presentation of Patient 1 [17, 18]. However, metastasis to the central nervous system is the most common site of distant spread by pleuropulmonary blastoma. Patient 1 did not receive chemotherapy after total resection of tumor due to the limited efficacy of chemotherapy against extracranial immature teratoma. In contrast, Patient 2 received intensive chemotherapy and remains in complete remission, although the initial tumor was incompletely resected. Therefore, this tumor was aggressive, and the patient may have benefited from adjuvant chemotherapy.

In summary, we present two infantile sacrococcygeal tumors mimicking immature teratoma in two unrelated children (one with germline pathogenic DICER1 variation) that may be a new subtype of DICER1-related infantile tumors. We had not previously seen tumors in this location in DICER1-carriers in the International Pleuropulmonary Blastoma Registry, suggesting they may be one of the rarer tumors associated with DICER1 pathogenic variation. We anticipate that an increased use of multi-gene next-generation sequencing panels may lead to further expansion of the spectrum of disease associated with DICER1. Recognition of a pathogenic germline DICER1 variant permits cascade genetic testing and potential identification of other family members at increased risk of malignancy. Surveillance guidelines and quantification of neoplasm risk for DICER1-carriers are available [19, 20].

This new entity, which we propose to call DICER1-associated presacral malignant teratoid neoplasm, may be difficult to distinguish from immature teratoma; however, recognition can facilitate appropriate classification as an aggressive malignancy and will facilitate appropriate genetic counseling, DICER1 germline variant testing, screening, and education.

References

Bernstein E, Caudy AA, Hammond SM, Hannon GJ. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature. 2001;409:363–6.

Hill DA, Ivanovich J, Priest JR, Gurnett CA, Dehner LP, Desruisseau D, et al. DICER1 mutations in familial pleuropulmonary blastoma. Science. 2009;325:965.

Foulkes WD, Priest JR, Duchaine TF. DICER1: mutations, microRNAs and mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:662–72.

Slade I, Bacchelli C, Davies H, Murray A, Abbaszadeh F, Hanks S, et al. DICER1 syndrome: clarifying the diagnosis, clinical features and management implications of a pleiotropic tumour predisposition syndrome. J Med Genet. 2011;48:273–8.

Khan NE, Bauer AJ, Doros L, Schultz KA, Decastro RM, Harney LA, et al. Macrocephaly associated with the DICER1 syndrome. Genet Med 2017;19:244–8.

Khan NE, Bauer AJ, Schultz KAP, Doros L, Decastro RM, Ling A, et al. Quantification of thyroid cancer and multinodular goiter risk in the DICER1 syndrome: a family-based cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:1614–22.

Brenneman M, Field A, Yang J, Williams G, Doros L, Rossi C, et al. Temporal order of RNase IIIb and loss-of-function mutations during development determines phenotype in pleuropulmonary blastoma/DICER1 syndrome: a unique variant of the two-hit tumor suppression model. F1000Res 2015;4:214.

McKenney JK, Heerema-McKenney A, Rouse RV. Extragonadal germ cell tumors: a review with emphasis on pathologic features, clinical prognostic variables, and differential diagnostic considerations. Adv Anat Pathol 2007;14:69–92.

Malagon HD, Valdez AM, Moran CA, Suster S. Germ cell tumors with sarcomatous components: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 46 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:1356–62.

Sebire NJ, Fowler D, Ramsay AD. Sacrococcygeal tumors in infancy and childhood; a retrospective histopathological review of 85 cases. Fetal Pedia Pathol 2004;23:295–303.

Heravi-Moussavi A, Anglesio MS, Cheng SW, Senz J, Yang W, Prentice L, et al. Recurrent somatic DICER1 mutations in nonepithelial ovarian cancers. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:234–42.

de Boer CM, Eini R, Gillis AM, Stoop H, Looijenga LH, White SJ. DICER1 RNase IIIb domain mutations are infrequent in testicular germ cell tumours. BMC Res Notes 2012;5:569.

Witkowski L, Mattina J, Schonberger S, Murray MJ, Choong CS, Huntsman DG, et al. DICER1 hotspot mutations in non-epithelial gonadal tumours. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:2744–50.

Sabbaghian N, Bahubeshi A, Shuen AY, Kanetsky PA, Tischkowitz MD, Nathanson KL, et al. Germ-line DICER1 mutations do not make a major contribution to the etiology of familial testicular germ cell tumours. BMC Res Notes 2013;6:127.

Rabinowits G, Barletta J, Sholl LM, Reche E, Lorch J, Goguen L. Successful management of a patient with malignant thyroid teratoma. Thyroid 2017;27:125–8.

Ward SP, Dehner LP. Sacrococcygeal teratoma with nephroblastoma (Wilm’s tumor): a variant of extragonadal teratoma in childhood. A histologic and ultrastructural study. Cancer 1974;33:1355–63.

Wessell A, Hersh DS, Ho CY, Lumpkins KM, Groves MLA. Surgical treatment of a type IV cystic sacrococcygeal teratoma with intraspinal extension utilizing a posterior-anterior-posterior approach: a case report. Childs Nerv Syst 2018;34:977–82.

Schneider DT, Wessalowski R, Calaminus G, Pape H, Bamberg M, Engert J, et al. Treatment of recurrent malignant sacrococcygeal germ cell tumors: analysis of 22 patients registered in the German protocols MAKEI 83/86, 89, and 96. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1951–60.

Schultz KAP, Williams GM, Kamihara J, Stewart DR, Harris AK, Bauer AJ, et al. DICER1 and associated conditions: identification of at-risk individuals and recommended surveillance strategies. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:2251–61.

Stewart DR, Best AF, Williams GM, Harney LA, Carr AG, Harris AK, et al. Neoplasm risk among individuals with a pathogenic germline variant in DICER1. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:668–76.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and family members for participating in this research. We thank M. Honda-Kitahara and R. Nagano for their technical support. This work is supported in part by the NCI Intramural Research Program, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Institutes of Health grant NCI R01CA143167 (Hill), the Japan Children’s Cancer Group (JCCG) and the Practical Research for Innovative Cancer Control from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, AMED [No. 17ck0106330h0001].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nakano, Y., Hasegawa, D., Stewart, D.R. et al. Presacral malignant teratoid neoplasm in association with pathogenic DICER1 variation. Mod Pathol 32, 1744–1750 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-019-0319-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-019-0319-4

This article is cited by

-

DICER1 tumor predisposition syndrome: an evolving story initiated with the pleuropulmonary blastoma

Modern Pathology (2022)

-

DICER1-associated sarcomas: towards a unified nomenclature

Modern Pathology (2021)

-

Clinicopathologic and molecular analysis of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the genitourinary tract: evidence for a distinct DICER1-associated subgroup

Modern Pathology (2021)

-

DICER1-associated sarcomas at different sites exhibit morphological overlap arguing for a unified nomenclature

Virchows Archiv (2021)

-

Pleuropulmonary blastoma-like peritoneal sarcoma: a newly described malignancy associated with biallelic DICER1 pathogenic variation

Modern Pathology (2020)