Abstract

Solid-state electrothermal energy interconversion utilising the electrocaloric effect is currently being considered as a viable source of applications alternative to contemporary cooling and heating technologies. Electrocaloric performance of a dielectric system is critically dependent on the number of uncorrelated polar states, or ‘entropy channels’ present within the system phase space. Exact physical origins of these states are currently unclear and practical methodologies for controlling their number and creating additional ones are not firmly established. Here we employ a multiscale computational approach to investigate the electrocaloric response of an artificial layered-oxide material that exhibits Goldstone-like polar excitations. We demonstrate that in the low-electric-field poling regime, the number of independent polar states in this system is proportional to the number of grown layers, and that the resulting electrocaloric properties are tuneable in the whole range of temperatures below TC by application of electric fields and elastic strain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrocaloric (EC) effect is defined as the variation of the dielectric material entropy as a function of the electric field at a given temperature, which results in an adiabatic temperature change. Recently, there has been significant progress1–3 in the development of polar (i.e., possessing spontaneous polarisation) dielectrics that display large EC temperature shifts ΔT under electric-field poling. These systems include a variety of ferroelectric ceramics,4–6 polymers7–10 and liquid crystals.11 A few relaxor and antiferroelectric materials may exhibit negative EC effect, which is especially advantageous for solid-state refrigeration.12 The best values of positive EC ΔT in modern nanoengineered materials range from 20 to 45 K, for electric-field sweeps ΔE⩾500 kV/cm,1–6,13,14 whereas negative EC ΔT remain below −10 K for much smaller ΔE.15–18

The magnitude of the EC ΔT is proportional to a logarithm of the number of possible polar states, or independent ‘entropy channels’ in the system.3,19 Therefore, it is highly desirable to acquire precise understanding of physical phenomena underpinning the emergence of these states and develop practical methods for engineering additional entropy channels into dielectrics. Moreover, since entropic changes involving evolution of other ferroic order parameters can be cumulative with the EC effect, more advanced multicaloric materials concepts blending polar, magnetic and elastic energy-interconversion functionalities, are also being considered.20–24

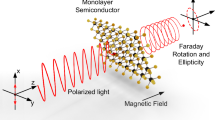

Here we use a multiscale computational approach that combines ab initio quantum mechanical simulations, phenomenological Landau theory and thermodynamical evaluations to investigate the EC response of a ‘material template’ based on a quasi-two-dimensional system that exhibits polar Goldstone-like25–27 excitations. This template system is an ‘n=2’ Ruddlesden-Popper (RP) type28 PbSr2Ti2O7 (PSTO) layered-oxide superlattice shown in Figure 1a. Such or similar materials have been successfully grown, e.g., by utilising molecular-beam epitaxy synthetic techniques.29–31

Crystal structure of PbSr2Ti2O7 and Goldstone-like energy surface. (a) Tetragonal unit cell consisting of two slabs connected by a body-centring translation (space group I4/mmm). Pb and Sr atoms are shown in red and blue, respectively, while the TiO6 cages are represented by light-blue semitranslucent octahedra. (b) Three-dimensional and (c) contour-map views of the system energy density function f with respect to developing in-plane polarisation P=(Px, Py) at . The energy of the paraelectric phase is taken as zero. The location of the polarisation vector within the minimum-energy ‘groove’ and its azimuthal angle θ are marked out in c for the shown Px, Py>0 quadrant of the energy surface.

The most interesting predicted feature of this system is that under biaxial basal-plane strains ranging from slight tensions (up to 0.2%) to modest compressions (up to 2%) it loses crystalline anisotropy with respect to the direction of its spontaneous polarisation P=(Px, Py),32 whereas rocksalt-type SrO–SrO inserts in between perovskite slabs prevent any polarisation in the out-of-plane direction z. The system free-energy density landscape f(Px, Py) is shown in Figure 1b and has a distinctive sombrero-hat shape characteristic of a presence of a Goldstone-like or phason excitation.25–27 In the case of PSTO, that excitation manifests itself as an easy—i.e., requiring almost no consumption of energy—rotation of P along the minimum-energy path within the basal plane, whereas its amplitude is kept constant.

This path, shown in greater detail in Figure 1c for zero biaxial strain, is only approximately circular—hence the ‘-like’ suffix above, as for the true Goldstone excitation it has to be a perfect circle. Here the absolute energy minima (at −6.26 meV per structural unit, or s.u.) are located along the [100], θ=0°, and three symmetrically equivalent crystallographic directions, and separated by saddle points (at −6.01 meV/s.u.) located along [110], θ=45°, and symmetrically equivalent directions. The competition between the [100]- and [110]-oriented sets of energy extrema can be controlled by applied strain; e.g., a small amount of tension can shift the minima to the [110] set of directions and saddle points to the [100] set.

Results

We have developed Landau-type polynomial expansions for f from ab initio calculations,32 including couplings to elastic strain and applied electric field E. Since RP structure does not support out-of-plane polar distortions,32,33 only the in-plane polarisation components were included. Also, only planar biaxial strain–tensor components , accounting for the epitaxial misfit strain on a square substrate, were considered in the expansion. Both linear and quadratic couplings involving ε were included to reproduce polarisation locking–unlocking phase transition under changing strain. With all the simplifications, this quasi-two-dimensional free-energy function is

The estimated system TC≃120 K, while the rest of the expression coefficients are given in Supplementary Information.

The equilibrium state of the system at a given temperature T and strain ε is determined by minimising f with respect to the polarisation vector components Px, Py. System excess heat capacity34 ΔC and pyroelectric coefficients , , can be obtained from the equilibrium values of polarisation (P0) and energy density f0≡f(P0) as

Then the adiabatic change in the system temperature ΔT under the influence of varying applied electric field E is35

where , , are changes in the x and y components of E during the poling procedure, and C(T) is the system heat capacity. Equations (1)–(4) were then used to study polarisation switching and the resulting temperature change ΔT in PSTO under applied field E. More details on the evaluation of both heat capacity terms and their influence on the magnitude of ΔT are provided in the Materials and Methods section below and in Supplementary Information.

Remarkably different types of the system polarisation behaviour are observed under conditions of either high-, or low-field poling. In the former case, i.e., for (depending on the value of ε), energy landscape shown in Figure 1 is deformed away from its original sombrero-hat shape. Application of a large electric field (Ex,a, Ey,b) creates a deep energy minimum along its direction, locking the polar vector P0 inside this minimum and destroying the Goldstone-like excitation. Poling field (ΔEx, ΔEy) then preserves the locked state of the polarisation. If the direction of E remains fixed during the poling, polarisation azimuthal angle θ stays constant, while only the amplitude changes value. Such amplitudon mode of polarisation switching is usually seen in conventional EC materials,5,6,34,35 where the largest variations in and thus the largest changes in and ΔT occur near TC.

In Figure 2a, we present the versus T dependence at different values of ε (see Supplementary Figure 1 for more details). This includes , where even at zero field the Goldstone-like excitation disappears in favor of a localised minimum along [110]. These results display transitional behaviour typical for a generic perovskite ferroelectric around TC.36 Curves for a number of different applied fields Ex,a=Ey,a are also shown for and, as expected, show a persistence of the polar phase beyond the zero-field TC. For the poling field , we obtain the values of ΔT in the range of 1–2 K (Supplementary Figure 2), which is similar to the performance of conventional EC materials undergoing amplitudon-polarisation switching.5,6,34,35

Amplitudon versus phason polarisation switching. (a) Temperature dependence of the zero-field polarisation amplitude at different biaxial strains. For the same dependence is shown in dashed lines for applied fields ranging from 40 to 120 kV/cm. Temperature dependence of the polarisation azimuthal angle (or phase) θ under (b) symmetrically, Ex,a≡Ey,a, and (c) asymmetrically, Ex,a≠Ey,a, applied static electric fields. In the former case, the polarisation vector abruptly locks with the direction of the field at some specific temperature Tlock, while in the latter case it smoothly aligns with the field.

In the case of low-field poling, i.e., for and , the sombrero-hat energy landscape is only slightly perturbed. If the [100] state of Figures 1b and c is taken as a starting point, applying noncollinear E induces a rotation of the polar vector along the minimum-energy groove until . During this rotation process, which we refer to as phason polarisation switching, its azimuthal angle θ changes while its amplitude remains approximately constant.

The θ(T) dependence for a number of different magnitudes of E is shown in Figure 2b and Figure 2c for symmetric, Ex,a≡Ey,a, and asymmetric, Ex,a≠Ey,a, static applied fields, respectively. Here, the polarisation is initially pointing towards the nearest energy minimum, so that, e.g., θ=0°, while the angle is <45°. In the both cases, it is observed that P can align with E only if sufficient energy is provided to the system in the form of heat. The temperature value at which the alignment happens (Tlock) can be adjusted by changing the magnitude of E throughout the whole temperature interval (0→TC), similarly to how the value of TC can be attuned by the applied strain ε during the amplitudon switching. However, for asymmetrically applied fields, the alignment of P with E always happens smoothly (see Figure 2c), not resulting in an emergence of large in the vicinity of Tlock. On the other hand, for symmetrically applied fields, polarisation alignment occurs abruptly (see Figure 2b; Supplementary Figure 3) and produces large pyroelectric response, which is strikingly similar to the behaviour of near TC during the high-field poling. The application of sufficiently large E—which is dependent on T—along [110] lowers the energy of the associated saddle point until it becomes the new energy minimum, while simultaneously raising the energy of the original minima along [100] and [010]. This creates a strong bias for locking P along the saddle-point direction, while such an incentive would be missing in the case of asymmetrically applied fields.

Since passage of the applied field through the saddle-point direction is accompanied by an emergence of large pyroelectric coefficients, which should in turn result in large EC ΔT, the following simple poling scenario can be considered. Starting with the polarisation along the x direction, θ=0°, a static field is applied, i.e., ΔEx=0 which eliminates one of the two integrals in Equation (4). Then, the field along the y direction is changed from to . This situation is illustrated step by step in Figure 3, which suggests that even for modest poling-field ramps ΔEy, bracketing the value of , it is possible to trigger rotation of P by an angle close to 90°, e.g., from the [100] energy minimum, through the saddle point along [110] and into the [010] energy minimum. The θ(T) plot in Figure 3b shows that initiates a smooth alignment of P with E, while only results in an abrupt switching of P between the two neighbouring basins within the energy landscape, after which it again smoothly aligns with E as T is raised above Tlock.

Phason-induced polarisation rotation and the resulting EC temperature change. (a) A step-by-step sketch of polarisation rotation under poling electric field Ey at and T=68 K. Energy-surface slices marked (1) through (3) correspond to the following states of the system: (1) P in vicinity of the minimum along [100], θ~0°, ; (2) P passing through the saddle point along [110], θ~45°, for ; (3) P switched into the equivalent minimum along [010], θ~90°, . Arrows represent approximate directions of P0 and E at steps (1) through (3). (b) θ(T) dependence under applied static electric field where (1) , (2) and (3) . Only in the latter case polarisation can switch from one energy minimum to the next, giving rise to a peak in the EC response. The complete poling sequence consists of sweeping Ey from (1) to (3) through (2) at fixed T. (c) Examples of the phason-induced EC response generated by this procedure highlight its tuneability: (i) and ΔEy=7 kV/cm, (ii) and ΔEy=17 kV/cm. The connection between an abrupt change of θ and the produced EC response (at some fixed ) is outlined by the rectangular selection spanning panels (b, c).

Figure 3c shows that abrupt changes in θ translate into large negative values of EC ΔT. As illustrated by the two different switching cases, the position of the phason EC peak on the temperature axis, as well as its width, can both be controlled purely by means of applied electric field—specifically by setting the values of and ΔEy, respectively. For example, changing from 5 to 13 kV/cm moves the center of the phason EC peak down from 60 to 30 K. Such precise tuning of the shape and location of the phason-induced EC response can be accomplished for all temperatures below TC. Typical maximum entropy changes achieved in this poling scenario are 0.5–1 J/kg/K (Supplementary Figure 4), similar to values observed by others for low-field switching.37

The negative sign of the phason-switching induced ΔT originates from the following consideration: as T→Tlock and polarisation rotation occurs, the angle is always diminished. Naturally, polarisation component after the rotation is always larger than component before the rotation, where γ is the direction along the field. Thus, the associated is positive, which results in negative ΔT according to Equation (4).

As shown in Figure 3c, abrupt changes of θ, each occurring under a specific fixed value of , result in an emergence of sharp bumps in the EC ΔT response. Furthermore, by choosing the values of the stationary field and the bracketing ΔEy poling interval, these peaks can be shifted to lower or higher temperatures on demand. When during the poling procedure Ey is swept continuously from to , individual peaks in the ΔT curve merge into an envelope that is presented in Figure 4 for different values of ε (see also Supplementary Figure 5). Remarkably, the variation of ε by ⩽1% can result in the system EC response changing from cooling (phason contribution) to heating (amplitudon contribution) at the same operating temperature.

Phason and amplitudon polarisation-switching contributions to the EC temperature change at different strains. All the presented curves are computed for and ΔEy=34 kV/cm. Note that for T near 70 K it should be possible to flip the sign of the EC response (i.e., switch from cooling to heating, or vice versa) by tuning the value of TC by applied strain.

Discussion

The EC temperature changes in PSTO in the low-field poling regime range from −50 to −100 mK, i.e., they are two orders of magnitude smaller compared to the (positive) ΔT values produced during the conventional, high-field poling. However, since, without the loss of generality, the quasi-two-dimensional form of f can describe the behaviour of a single slab whose polarisation is decoupled from those of its neighbours, cumulative EC ΔT in a multi-slab system should look very different for the high- and low-field poling cases. It is noteworthy that the approximation of electrically decoupled polar slabs is already quite good for bulk PSTO, as illustrated by an absence of phonon-band dispersion for polar modes in the direction perpendicular to the slab planes; see Figure 2 in reference 32.

In the high-field regime, individual slab polarisations are switched ‘all at once,’ being forcefully correlated by the applied field. That is, the multi-slab system possesses only one entropy channel and the value of ΔT≃1–2 K quoted above for PSTO should represent its aggregate EC response. In the low-field regime, applied fields are insufficient to correlate the directions of (disordered) polar vectors in different slabs and, therefore, polarisation rotations under the cycling of the field should occur independently in each slab. In such a case, each slab acts as a separate entropy channel and the aggregate EC response of the whole system should be proportional to the logarithm of the number of slabs. Then, even with individual slab contributions being low (~100 mK for PSTO), a system comprised of a large number of slabs should possess an aggregate ΔT that is at least comparable with other state-of-the-art negative EC materials.15–18

The estimate of one entropy channel per slab is conservative, as in the model presented here any influence of polar domain-wall dynamics on the EC response is not taken into account, i.e., each slab is considered to be in a monodomain state. An investigation of polarisation-closure patterns in PSTO nanostructures predicted that these patterns are likely to form and their behaviour sensitively depends on the applied strain,38 suggesting that multiple entropy channels may be created (or destroyed, if needed) in each slab by distorting its shape. Alternatively, a nano-island device geometry, where polar states of individual islands uncorrelated from each other, can be used instead of a continuous-film one.

In summary, we have shown that layered polar systems with Goldstone-like instabilities should exhibit attractive EC properties that are highly tunable by applying electric fields and elastic distortions over a wide range of operating temperatures below TC, which may even include on-demand switching between cooling and heating. By virtue of operating at low electric fields, device applications of actual materials will require modest power consumption, compared with most other known EC compounds, where fields of upwards of 500 kV/cm are needed for best performance. Furthermore, in such model systems the mechanisms behind the emergence of independent entropy channels can be clearly established allowing for an easy up- or down-scaling of the system entropy-flow and EC characteristics by growing an appropriate number of layers. Although for the specific example of PSTO, a single monodomain-slab EC response in the low-field operation is only around 0.1 K, it should be possible to employ ‘materials by design’ principles to develop new compounds with improved EC properties. The competition between the [100]- and [110]-oriented sets of energy minima in polar-perovskite layers, leading to Goldstone-like excitations, appears to be a generic geometrical feature of such systems, rather than a peculiar trait distinctive to PSTO. We have recently identified other layered-oxide structures that should possess similar properties.39

Materials and methods

Ab initio calculations were performed with the density-functional theory code Quantum Espresso40 utilising local-density approximation in the Perdew–Zunger parametrisation41 and Vanderbilt ultrasoft pseudopotentials.42 Vibrational frequencies, ionic displacement patterns and system vibrational density of states, were obtained using density-functional perturbation theory approach within Quantum Espresso.43 The system total heat capacity C(T), used in Equation (4) above, was evaluated from the vibrational density of states44,45 computed for the non-polar system configuration (see Supplementary Information and Supplementary Figure 6 for more details).

Ionic forces were relaxed to less than 0.2×10−5 Ry/bohr (~0.5×10−4 eV/Å) and the appropriate stress tensor components (α and β are Cartesian directions x, y and z) were converged to values below 0.2 kbar. Epitaxial thin-film constraint on a cubic (001)-oriented substrate was simulated by varying the in-plane lattice constant a of the tetragonal cell and allowing the out-of-plane lattice constant c to relax (by converging the normal stress in this direction to a small value), while preserving the imposed tetragonal unit-cell symmetry. The biaxial misfit strain ε is defined as (a−a0)/a0, where a0 is the in-plane lattice parameter of the free standing PSTO structure with all the normal stress tensor components relaxed to <0.2 kbar.

Ionic Born effective-charge tensors , where i is the ion number, and high-frequency dielectric permittivity tensor were calculated by utilising the density-functional perturbation theory approach. The system polarisation was evaluated with a linearised approximation46 involving products of and ionic displacements away from centrosymmetric positions. The value of TC (~120 K) was estimated from energy differences between the non-polar I4/mmm and polarised [100], and [110] states of the system.

We should point out that due to the purely analytical nature of our approach it does not account for spatial inhomogeneities of the polarisation P and elastic-field variables. Such inhomogeneities can be present in epitaxially clamped thin films producing additional contributions to the aggregate ΔT that stem from, e.g., elastocaloric effects and polydomain behaviour. Although we have not yet studied piezoelectric response of PSTO in detail, we expect most of its piezoelectric coefficients to be low—with the same being true about the magnitude of the intrinsic elastocaloric effect—as polarisation rotation in this material is not accompanied by large elastic distortions. Instead of utilising the Maxwell relation (3), a number of approaches involving combinations of effective-Hamiltonian techniques with molecular dynamics or Monte Carlo simulations have been used to directly compute field-induced temperature and entropy changes in ferroelectrics.47–49 (Such techniques can indeed handle polar and elastic spatial inhomogeneities when appropriately parameterised.) Although with no first-order phase transitions present both types of approaches should produce the same results,49 the accuracy of the type adopted here may depend on precision of numerical integration of the Maxwell relations.47 We have investigated convergence of the integral in Equation (4) for the poling schemes described above, with variations ⩽15–20% found for the resulting ΔT, as long as step of numerical sweeping of the poling field was not too small (typical step values ranged from 0.5 to 0.05 kV/cm).

References

Scott, J. F. Electrocaloric materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 41, 230–240 (2011).

Valant, M. Electrocaloric materials for future solid-state refrigeration technologies. Prog. Mater. Sci. 57, 980–1009 (2012).

Alpay, S. P., Mantese, J., Trolier-McKinstry, S., Zhang, Q. & Whatmore, R. W. Next-generation electrocaloric and pyroelectric materials for solid-state electrothermal energy interconversion. MRS Bull. 39, 1099–1111 (2014).

Mischenko, A. S., Zhang, Q., Scott, J. F., Whatmore, R. W. & Mathur, N. D. Giant electrocaloric effect in thin-film PbZr0.95Ti0.05O3 . Science 311, 1270–1271 (2006).

Chen, H., Ren, T.-L., Wu, X. M., Yang, Y. & Liu, L.-T. Giant electrocaloric effect in lead-free thin film of strontium bismuth tantalite. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 182902 (2009).

Bai, Y., Guangping, Z. & Sanqiang, S. Direct measurement of giant electrocaloric effect in BaTiO3 multilayer thick film structure beyond theoretical prediction. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 192902 (2010).

Neese, B. et al. Large electrocaloric effect in ferroelectric polymers near room temperature. Science 321, 821–823 (2008).

Lu, S.-G. & Zhang, Q. Electrocaloric materials for solid-state refrigeration. Adv. Mater. 21, 1983–1987 (2009).

Lu, S. G. et al. Comparison of directly and indirectly measured electrocaloric effect in relaxor ferroelectric polymers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 202901 (2010).

Li, B. et al. Intrinsic electrocaloric effects in ferroelectric poly(vinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene) copolymers: Roles of order of phase transition and stresses. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 102903 (2010).

Qian, X.-S. et al. Large electrocaloric effect in a dielectric liquid possessing a large dielectric anisotropy near the isotropic-nematic transition. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 2894–2899 (2013).

Correia, T. & Zhang, Q. Electrocaloric Materials: New Generation of Coolers (Springer-Verlag, 2014).

Peng, B., Fan, H. & Zhang, Q. A giant electrocaloric effect in nanoscale antiferroelectric and ferroelectric phase coexisting in a relaxor Pb0.8Ba0.2ZrO3 thin film at room temperature. Adv. Mater. 23, 2987–2992 (2013).

Khassaf, H., Mantese, J. V., Bassiri-Gharb, N., Kutnjak, Z. & Alpay, S. P. Perovskite ferroelectrics and relaxor-ferroelectric solid solutions with large intrinsic electrocaloric response over broad temperature ranges. J. Mater. Chem. C 4, 4763–4769 (2016).

Li, B. et al. The coexistence of the negative and positive electrocaloric effect in ferroelectric thin films for solid-state refrigeration. Europhys. Lett. 102, 47004 (2013).

Axelsson, A.-K. et al. Microscopic interpretation of sign reversal in the electrocaloric effect in a ferroelectric PbMg1/3Nb2/3O3-30 PbTiO3 single crystal. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 102902 (2013).

Pirc, R., Rožič, B., Koruza, J., Malic, B. & Kutnjak, Z. Negative electrocaloric effect in antiferroelectric PbZrO3 . Europhys. Lett. 107, 17002 (2014).

Geng, W. et al. Giant negative electrocaloric effect in antiferroelectric La-doped Pb(ZrTi)O3 thin films near room temperature. Adv. Mater. 27, 3165–3169 (2015).

Pirc, R., Zutnjak, Z., Blinc, R. & Zhang, Q. M. Upper bounds on the electrocaloric effect in polar solids. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 021909 (2011).

Fähler, S. et al. Caloric effects in ferroic materials: new concepts for cooling. Adv. Engr. Mater. 14, 10–19 (2012).

Lisenkov, S., Mani, B. K., Change, C.-M., Almand, J. & Ponomareva, I. Multicaloric effect in ferroelectric PbTiO3 from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 87, 224101 (2013).

Liu, Y. et al. Giant room-temperature elastocaloric effect in ferroelectric ultrathin films. Adv. Mater. 26, 6132–6137 (2014).

Moya, X., Kar-Narayan, S. & Mathur, N. Caloric materials near ferroic phase transitions. Nat. Mater. 13, 439–450 (2014).

Takeuchi, I. & Sandeman, K. Solid-state cooling with caloric materials. Phys. Today 68, 48–54 (2015).

Goldstone, J., Salam, A. & Weinberg, S. Broken Symmetries. Phys. Rev. 127, 965–970 (1962).

Bruce, A. D. & Cowley, R. A. Structural Phase Transitions (Taylor and Francis Ltd., 1981).

Muševič, I., Blinc, R. & Žekš, B. The Physics of Ferroelectric and Antiferroelectric Liquid Crystals (World Scientific, 2000).

Ruddlesden, S. N. & Popper, P. New compounds of the K2NiF4 type. Acta Cryst. 10, 538–539 (1957).

Haeni, J. H. et al. Epitaxial growth of the first five members of the Srn+1TinO3n+1 Ruddlesden-Popper homologous series. Appl. Phys. Lett. 78, 3292 (2001).

Lee, J. H. et al. Dynamic layer rearrangement during growth of layered oxide films by molecular beam epitaxy. Nat. Mater. 13, 879–883 (2014).

Nie, Y. F. et al. Atomically precise interfaces from non-stoichiometric deposition. Nat. Commun. 5, 4530 (2014).

Nakhmanson, S. M. & Naumov, I. Goldstone-like states in a layered perovskite with frustrated polarization: A first-principles investigation of PbSr2Ti2O7 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 097601 (2010).

Bousquet, E., Junquera, J. & Ghosez, P. First-principles study of competing ferroelectric and antiferroelectric instabilities in BaTiO3/BaO superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 82, 045426 (2010).

Akcay, G., Alpay, S. P., Rossetti, G. A. & Scott, J. F. Influence of mechanical boundary conditions on the electrocaloric properties of ferroelectric thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 103, 024104 (2008).

Zhang, J., Misirlioglu, I. B., Alpay, S. P. & Rossetti, G. A. Electrocaloric properties of epitaxial strontium titanate films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 222909 (2012).

Strukov, B. A. & Levanyuk, A. P. Ferroelectric Phenomena in Crystals, Physical Foundations (Springer, 1998).

Moya, X. et al. Giant electrocaloric strength in single-crystal BaTiO3 . Adv. Mater. 25, 1360–1365 (2013).

Lee, B., Nakhmanson, S. M. & Heinonen, O. Strain induced vortex-to-uniform polarization transitions in soft-ferroelectric nanoparticles. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 262906 (2014).

Louis, L. & Nakhmanson, S. M. Structural, vibrational, and dielectric properties of Ruddlesden-Popper Ba2ZrO4 from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 91, 134103 (2015).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Cond. Matt. 21, 395502 (2009).

Perdew, J. P. & Zunger, A. Self-interaction correction to density-functional approximations for many-electron systems. Phys. Rev. B 23, 5048–5079 (1981).

Vanderbilt, D. Soft self-consistent pseudopotentials in a generalized eigenvalue formalism. Phys. Rev. B 41, 7892–7895 (1990).

Baroni, S., de Gironcoli, S., Dal Corso, A. & Giannozzi, P. Phonons and related crystal properties from density-functional perturbation theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 515–562 (2001).

Maradudin, A. A. Theory of Lattice Dynamics in the Harmonic Approximation (Academic Press, 1971).

Nakhmanson, S. & Drabold, D. A. Low-temperature anomalous specific heat without tunneling modes: A simulation for a-Si with voids. Phys. Rev. B 61, 5376–5380 (2000).

Nakhmanson, S. M., Rabe, K. M. & Vanderbilt, D. Polarization enhancement in two- and three-component ferroelectric superlattices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 87, 102906 (2005).

Ponomareva, I. & Lisenkov, S. Bridging the macroscopic and atomistic descriptions of the electrocaloric effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 167604 (2012).

Ma, Y.-B., Albe, K. & Xu, B.-X. Lattice-based monte carlo simulations of the electrocaloric effect in ferroelectrics and relaxor ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. B 91, 184108 (2015).

Marathe, M., Grünebohm, A., Nishimatsu, T., Entel, P. & Ederer, C. First-principles-based calculation of the electrocaloric effect in BaTiO3: A comparison of direct and indirect methods. Phys. Rev. B 93, 054110 (2016).

Acknowledgements

S.N., K.C.P. and J.M. are grateful to the National Science Foundation (DMR 1309114) for partial funding of this project. S.N. also thanks Olle Heinonen and Joseph Mantese for illuminating discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.N. and S.P.A. developed the multiscale theoretical framework and supervised the project. S.N. and K.C.P. performed all the DFT simulations. J.M. fitted the Landau-type energy expressions from the DFT results and conducted thermodynamical modeling. J.M., S.N. and S.P.A. co-wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the npj Computational Materials website (http://www.nature.com/npjcompumats)

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Mangeri, J., Pitike, K., Alpay, S. et al. Amplitudon and phason modes of electrocaloric energy interconversion. npj Comput Mater 2, 16020 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/npjcompumats.2016.20

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npjcompumats.2016.20

This article is cited by

-

Giant room temperature elastocaloric effect in metal-free thin-film perovskites

npj Computational Materials (2021)

-

Negative thermal expansion: Mechanisms and materials

Frontiers of Physics (2021)

-

Landau–Devonshire thermodynamic potentials for displacive perovskite ferroelectrics from first principles

Journal of Materials Science (2019)

-

A thermodynamic potential for barium zirconate titanate solid solutions

npj Computational Materials (2018)

-

The origin of uniaxial negative thermal expansion in layered perovskites

npj Computational Materials (2017)