Abstract

Self-assembled nanotubular structures have numerous potential applications but these are limited by a lack of control over size and functionality. Controlling these features at the molecular level may allow realization of the potential of such structures. Here we report a new generation of self-assembled cyclic peptide–polymer nanotubes with dual functionality in the form of either a Janus or mixed polymeric corona. A ‘relay’ synthetic strategy is used to prepare nanotubes with a demixing or mixing polymeric corona. Nanotube structure is assessed in solution using 1H–1H nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy NMR, and in bulk using differential scanning calorimetry. The Janus nanotubes form artificial pores in model phospholipid bilayers. These molecules provide a viable pathway for the development of intriguing nanotubular structures with dual functionality via a demixing or a mixing polymeric corona and may provide new avenues for the creation of synthetic transmembrane protein channel mimics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The exploitation of molecular self-assembly processes using relatively simple building blocks is a powerful approach for the design and creation of ensembles of energy efficient, ordered, hierarchical nanostructures1,2,3,4. The simplicity of this bottom-up approach together with the resultant uniformity and size of the self-assembled nanoscopic structures provides an attractive strategy, which favours applicability in the field of nanoscience and nanotechnology5. Among the different types of self-assembled architectures, nanotubular structures have gained considerable interest because of their suitability for various applications including nanomedicine6,7, (bio)sensing8,9, separation and recovery technologies10 as well as nanoelectronics11. A distinct feature of tubular structures that is often absent from traditional self-organized supramolecular structures for example, micelles and vesicles, is the internal channel cavity, which in the case of self-assembled nanotubes (NTs) has a defined diameter that can provide a means for selective transport or molecular encapsulation properties. Although several types of nanotubular structure exist including carbon NTs12, metal sulphide and metal oxide complexes13, many of these suffer from low solubility, high toxicity, limited opportunities for chemical modification and poor control over size and uniformity. In contrast, peptide-based NTs offer ample opportunity for chemical modification. Moreover, chemical functionality can be added or replaced, toxicity can be reduced and solubility can be tuned with relative ease compared with non-peptidic NTs. The accessibility of standardized and automated synthesis protocols also enables synthetic tailoring of peptides by careful choice of the amino-acid building blocks.

A fascinating class of peptides that are known to self-assemble into supramolecular NTs are cyclic peptides (CPs) comprising 4, 6, 8, 10 or 12 alternating D- and L-amino acids14,15. The alternating chirality of the amino acids in the macrocycle leads to amide bonds that alternate in orientation perpendicular to the plane of the CP rings16. As a result, a contiguous intermolecular hydrogen-bonded network arises, resulting in the formation of nanotubular structures. This strong hydrogen bonding facilitates purification of CP NTs through precipitation of aggregates, thus obviating the need for chromatographic purification. Further, the planar structure of the CP backbone projects the peptide side chains from the external periphery leaving a hollow channel with a van der Waals diameter ranging from 0.2 to 1.3 nm, for CPs incorporating 4–12 amino-acid residues, respectively14,15,17,18,19. Although a range of CPs with different ring sizes can be synthesized, model studies using N-alkylated CP dimers indicate that CPs with eight amino-acid residues have the highest association constants15,20. The formation of NTs from cyclic octapeptides conjugated to large molecules such as fullerene, redox responsive dyes and polymers demonstrates the high fidelity of interpeptide hydrogen bonding in these systems despite substantial steric hindrance15.

Although tremendous progress has been made with CP NTs in applications such as ion sensing8, transbilayer ion channels21 and as antibacterials22, limitations with respect to modulation of NT solubility, functionality and lack of control over NT length restrict the diversification of applications. In addition, uniformity and reproducibility of NT formation via self-assembly are imperative for the bottom-up production of functional nanomaterials. To a large extent, CP–polymer conjugates, whereby the CP has been used as a supramolecular template, have addressed these issues23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. For instance, the polymer conjugate allows for some degree of control over the tube length, and the nature of the grafted polymer also permits tuning the solubility of the CP–polymer NTs in solvents that are usually incompatible with NTs made from CPs alone. However, the fine control over the polymer corona of the CP–polymer NTs required for many applications has not yet been achieved. For instance, there are no previous examples in which dual functionality is introduced into the corona of the NTs, either as hybrid ‘mixed’ corona or as ‘demixed’ corona, for example, to form Janus CP–polymer NTs. Although several examples of polymeric Janus micelles in the form of discs31,32, cylinders33,34 and spheres35 have been reported, none of these self-assembled nanostructures contain a well-defined subnanometre channel cavity as would be the case for Janus NTs.

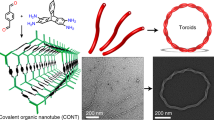

We report herein the fabrication of the first Janus CP–polymer NTs, as illustrated in Fig. 1, constructed via a two-step convergent synthetic approach using well-defined polymer and CP-building blocks and orthogonal ligation strategies, including for the first time thiol-ene chemistry. The use of a CP containing eight alternating D- and L-amino acids permits a facile templated approach for the formation of well-defined NTs featuring subnanometre channels within their cores. The Janus character of the CP–polymer NTs is assessed in both solution and in bulk. In appropriate solvents, self-assembly is observed to occur at ambient temperatures resulting in well-defined nanotubular structures.

Results

Synthesis and characterization

A linear peptide (1), with appropriately functionalized alternating L- and D- amino acids (H2N-L-Trp(Boc)-D-Leu-L-Lys(N3)-D-Leu-L-Trp(Boc)-D-Leu-L-Lys(Alloc)-D-Leu-OH) was synthesized via solid-phase peptide synthesis (Fig. 2). Following cyclization of 1 and subsequent deprotection using trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), the CP (2) was obtained with the Alloc side chain-protecting group intact. To generate thiol-terminated polymers, the chain transfer agent (propanoic acid)yl butyl trithiocarbonate (PABTC) was used in reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization followed by aminolysis of the butyl trithiocarbonate. Aminolysis of the butyl trithiocarbonate chain-end of polystyrene (PS) under ambient conditions yielded thiol-terminated PS polymers with no broadening of the molecular weight distribution because of the formation of disulphide bonds (Supplementary Fig. S1 for ultraviolet–visible size exclusion chromatography (SEC) of non-modified and aminolysed PS35, PS68 and PS100). For the production of alkyne-terminated polymers, PABTC was first esterified at the carboxylic acid with propargyl alcohol to yield (prop-2-ynyl propanoate)yl butyl trithiocarbonate (PYPBTC) before polymerization36,37. This strategy demonstrates the ubiquity of the precursor PABTC in its use for the production of both thiol-terminated polymers and alkyne-terminated polymers. In addition, the terminal –CH3 on the ω-terminal butyl group of PABTC and PYPBTC is used to calibrate 1H-NMR integrals for determining the degree of polymerization, as this peak (~0.9 p.p.m.) does not overlap with protons on the polymer backbone and polymer side chains (>1 p.p.m.).

Synthesis of hybrid CP–polymer conjugates can be achieved via copper-catalysed azide–alkyne cycloaddition followed by a photochemical thiol-ene reaction (route on left hand side) or via photochemical thiol-ene reaction followed by a copper-catalysed azide–alkyne cycloaddition (route on right hand side). The thicker arrows indicate the preferred pathway based on yields for obtaining hybrid CP–polymer conjugates.

To construct the envisioned Janus CP–polymer NTs, two different polymers that are known to undergo microphase separation were attached to the CP. PS and poly(n-butyl acrylate; PBA) were chosen as non-miscible polymers (a Flory–Huggins interaction parameter38, χPS-PBA~0.1 was determined using molar volume and energy of vapourization39 contributions of the PS and PBA repeat units). Miwa et al.40 have previously shown with differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) experiments that PS-PBA diblock copolymers have two distinct glass transition temperatures (Tg) at ~95 and −50 °C, corresponding to the Tg values of PS and PBA blocks, respectively. This observation implies that the PBA and PS polymer chains are not miscible. In contrast, blends of poly(cyclohexyl acrylate) (PCHA) and PS have been reported to exhibit a single Tg between the Tg of the PS (~95 °C) and PCHA (~17 °C)41,42, indicating their miscibility in bulk (Table 1). Therefore, for comparison with our Janus structures, hybrid CP–polymer conjugates bearing both PS and PCHA units, which should form a single microphase corona (χPS-PCHA~0.03) were also prepared.

Figure 2 outlines the synthesis of the CP–polymer conjugates, which can be achieved via two synthetic pathways; (i) copper-catalysed azide–alkyne cycloaddition/thiol-ene (CuAAC/thiol-ene) or (ii) thiol-ene/CuAAC. The first step in the CuAAC/thiol-ene pathway involved the conjugation of an alkyne-terminated PBA or PCHA to the azidolysine side chain of 2 via microwave-assisted CuAAC to yield a one-armed CP–polymer intermediate (3–7). Microwave-assisted CuAAC has previously been shown to yield high conversions for CP–polymer conjugates using 10 mol% excess polymer relative to the CP bearing two azidolysine residues24,26. Similarly, complete conversions of CuAAC of the alkyne-terminated polymers PBA or PCHA to 2 were achieved with 5 mol% excess relative to the CP bearing one azidolysine residue, as evidenced by the appearance of the triazole resonance at ~8.5 p.p.m. in the 1H-NMR spectra of the conjugates obtained in a mixture of TFA (50 vol%) and deuterated chloroform (50 vol%; Supplementary Fig. S2). This solvent mixture was used because TFA disrupts aggregation and allows individual conjugates to be analysed in solution. Characterization of the individual CP–polymer conjugates is difficult to achieve because of the tendency of the CP moiety to self-assemble. When performing 1H-NMR analysis of the CP–polymer conjugates in pure deuterated chloroform, only the proton peaks corresponding to the unconjugated polymers or polymers conjugated to the CP were visible. The proton peaks corresponding to the groups present on the CP are not visible, as the chloroform cannot solvate the CP core of the NTs, its access being prevented by the polymeric shell. Although this provides remarkable evidence of the association of the CP–polymer conjugates into NTs, it also highlights the challenges associated with their characterization, which often relies on complete solubility in solvents.

In addition to 1H-NMR, Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy was used to assess CuAAC conversion. As shown in Fig. 3a, conjugation of 2 with an alkyne-terminated PCHA63 resulted in the total disappearance of the azide peak in the FT-IR spectra, confirming complete consumption of the azide starting material to yield a one-armed CP–polymer conjugate intermediate. After washing to remove residual copper catalyst and recovery of the one-armed CP–polymer conjugate, a thiol-terminated PS was coupled to the Alloc-protected L-lysine side chain via a photochemical thiol-ene reaction. For the synthesis of the CP–polymer conjugates 11, 13, 15 and 17, 1H-NMR analysis based on the disappearance of the alkene resonance at ~5.8 p.p.m. revealed that the photochemical thiol-ene addition led to high conversions (~80%).

(a) The CuAAC/thiol-ene relay reaction of the conjugation of alkyne-terminated PCHA63 to the CP 2 and the subsequent conjugation of aminolysed PS68 to the PCHA63CP–Lys(Alloc) intermediate 6 to yield two-armed CP–polymer conjugate 16. (b) The thiol-ene/CuAAC relay reaction of the conjugation of aminolysed PS68 to the CP 2 followed by the coupling of the alkyne-terminated PBA71 to the PS68-CP-Lys(N3) to yield two-armed CP–polymer conjugate 14. The azide, amide I and II stretches and the N–H stretch region are shown. The spectra are vertically offset to aid clarity.

The alternative pathway in which the conjugation of a thiol-terminated PS with the CP to yield one-armed CP–polymer conjugates 8 and 9 was followed by CuAAC of the alkyne-terminated PBA polymer to yield two-armed CP–polymer conjugates 12 and 14 was also explored. Notably, the photochemical thiol-ene reaction did not result in loss of the azide moiety present on the CP, as confirmed by the presence of the azide peak in the FT-IR spectra after performing the thiol-ene reaction (Fig. 3b), demonstrating the remarkable orthogonality of the two conjugation chemistries. However, the conversion of the photochemical thiol-ene addition of PS via the thiol-ene/CuAAC pathway was significantly lower (~ 60–80%) than the conversions obtained after CuAAC of PBA or PCHA via the CuAAC/thiol-ene pathway (Table 2). The difference in thiol-ene conversions was consistent for the conjugation of the PS35, PS68 and PS100 polymers and was attributed to the limited solubility of the CP in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF). Although complete CuAAC conversion between a one-armed CP–PS68 intermediate and an alkyne-terminated polymer was observed (Fig. 3b), the CuAAC/thiol-ene relay reaction was established as the favoured pathway for the formation of two-armed CP–polymer conjugates because of the higher overall conversions.

Self-assembly and Janus character of NTs

Figure 3 presents the FT-IR spectra of the unmodified CP (2), the one-armed CP–polymer intermediates (6, 9) and the final two-armed CP–polymer hybrids (14, 16) synthesized via either the CuAAC/thiol-ene relay or the thiol-ene/CuAAC relay reactions. For the CP 2, CP–polymer intermediates as well as final hybrid CP–polymer products, β-sheet formation was confirmed by the observation of the amide I and amide II bands at 1,625 and 1,532 cm−1, respectively, in their FT-IR spectra (Fig. 3). In addition, the N–H stretching vibration observed at 3,274 cm−1 confirmed a tight network of interpeptide hydrogen bonding within the CP–polymer conjugates, which is a strong indication of the formation of NTs. Further evidence for the formation of CP–polymer NTs was supported by dynamic light scattering (DLS) experiments from which NT hydrodynamic radii of 70–200 nm in both chloroform and tetrahydrofuran were observed (Table 2). The hydrodynamic radii increased with a decrease in polymer molecular weight, as previously observed for other CP–polymer NTs23,24. Finally, small-angle neutron scattering experiments on PBA71-CP-PS68 conjugate 13 and PCHA63-CP-PS68 conjugate 16 in deuterated chloroform confirm NT formation. A q−1 dependency at low scattering angles was observed, as expected from rod-like structures, and the data were fitted to a core-shell cylinder model (Supplementary Fig. S3). 1H-NMR also proved very valuable in the characterization of the NT structure. Although 1H-NMR spectra obtained in good solvents for the CP and polymer corona alike (for example, 50% TFA and 50% CDCl3) proved useful for the characterization of the conjugation efficiency above, performing experiments in a good solvent for the polymer but a poor solvent for the CP (for example, CDCl3) gave valuable information about the self-assembly behaviour of the conjugates.

Figure 4 shows the two-dimensional (2D) 1H–1H Nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) NMR contour plot of the CP–polymer NT derived from PCHA63-CP-PS68 (16), in which cross-relaxation peaks are observed between the protons of the PCHA side chain with those of the PS side chain (4.7 p.p.m. on the f1-axis and 6.6 p.p.m. on the f2-axis) as well as between the PCHA backbone protons and the PS side chain protons (2.3 p.p.m. on the f1-axis and 6.5 p.p.m. on the f2-axis). This indicates that the polymer chains in conjugate 16 form a mixed corona, as expected from the Flory–Huggins analysis (χN≤2). In contrast, the 2D 1H–1H NOESY NMR contour plot of the CP NT derived from PBA71-CP-PS68 (13) (Fig. 5) shows only cross-relaxation peaks between the backbone and the side chain protons of the PBA polymer chains as well as between the backbone and side chain protons of the PS polymer chains. The Janus character of the NTs with mixing polymer pairs (16) was also assessed after the addition of TFA. In contrast to the 1H–1H NOESY contour plot obtained for 16 in CDCl3 that indicates mixing of the two polymers, in the presence of TFA no cross-peaks are observed between the PCHA and PS side chains indicating that in this solvent the polymer chains attached to the CP core are separated by a distance greater than 0.5 nm (Supplementary Fig. S4) thus confirming the disassembly of the NTs under these conditions. The Janus character of these nanotubes can thus be observed in solution by judicious use of mixing and demixing polymer pairs as well as through use of a variety of solvents promoting either self-assembly or disassembly of the NTs. Probing the Janus character of CP–polymer NTs with shorter polymer chains (for example, PBA36-CP-PS35 conjugate 11 or PCHA34-CP-PS35 conjugate 15) did not reveal cross-relaxation peaks (Supplementary Figs S5 and S6). This was attributed to either the incompatibility of the polymer chains (11) or to incomplete cross-relaxation due to the dynamic nature of the short polymer chains (15).

2D 1H–1H NOESY NMR contour plot of a PCHA63-CP-PS68 conjugate 16 in CDCl3 at room temperature (a) and a zoomed in inset (b). The NOE signals observed between PS68 and PCHA63 polymers are indicated with a purple circle. The NOE signals attributed to interactions between the PS68 polymer chains are circled in blue and the NOE signals attributed to interactions between the PCHA63 polymer chains are circled in red.

2D 1H–1H NOESY NMR contour plot of a PBA71-CP-PS68 conjugate 13 in CDCl3 at 300 K. The NOE signals that would be observed in the case of mixing of the PS68 and PBA71 polymer chains are indicated with a purple circle. The NOE signals that belong to PS68 are circled in blue and the NOE signals that belong to the PBA71 are circled in red.

DSC measurements were performed to assess the presence and shifts of the Tg of the polymers when attached to the CP (Tables 1 and 2). As shown in Fig. 6, DSC analysis of the CP–polymer conjugates with a corona consisting of demixing polymer pairs (PS68-CP-PBA71 conjugate 13) exhibited two glass transitions that correspond to the PBA and PS polymers at approximately −44 and 85 °C, respectively. Similarly, two Tg values corresponding to the PS and PBA polymer blocks observed in CP–polymer conjugates 11, 12 and 14 suggested that the relay-coupling pathway and the overall differences in conjugation efficiencies had little influence on the Janus behaviour of the CP–polymer NTs in bulk. Further, this observation agrees well with DSC experiments performed on PS-PBA diblock copolymers40. DSC analysis of the hybrid CP–polymer conjugate 16, which has a mixing corona consisting of a pair of miscible polymers (PCHA63 and PS68), exhibited a single Tg at 44 °C above the Tg of PCHA63 and below the Tg for PS68 (Fig. 6b). Despite the absence of cross-relaxation between the PCHA34 and PS35 on CP–polymer conjugate 15 (Supplementary Fig. S6), DSC analysis revealed a single, broad Tg at 53 °C, which was well above the Tg for PCHA34 (0 °C) and well below the Tg for PS35 (79 °C), suggesting that indeed polymer mixing is taking place in bulk. The Tg value observed for conjugate 17 was lower than that observed for 15 and 16 and could reflect the lower PS100 composition owing to slightly lower thiol-ene coupling efficiency (Supplementary Figs S7 and S8).

(a) Glass transitions of the polymers PBA71 and PS68 and the Janus conjugate PBA71-CP-PS68 (13) in which two transitions correspond to the PBA71 and PS68 polymer arms. (b) Glass transitions of the polymers PCHA63, PS68 and the ‘mixed’ hybrid conjugate PCHA63-CP-PS68 (16) in which one transition corresponds to the mixing of the PCHA63 and PS68 polymer arms. The numbers indicate the temperatures at the start and end of the glass transition.

Pore formation in lipid bilayers

The properties of Janus NTs as nanopores were assessed following the well-established technique published by Ghadiri et al.21, in which a fluorescent dye is encapsulated in large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs). On disruption of the lipid bilayer, the flux of protons into the LUV results in a decrease in fluorescence. As copper is known to quench the fluorescence43, the conjugates used in this assay were prepared by replacing the CuAAC with a copper-free ligation technique. As shown in Fig. 7a, a consecutive active ester/thiol-ene reaction with N-hydroxysuccinimidyl ester α-end-functionalized PBA71 and thiol end-functionalized PS68, respectively, was carried out on CP 18 to yield Janus conjugate PBA71-CP-PS68 19. To compare the lipid bilayer-partitioning behaviour of Janus conjugate 19 with a non-Janus NT equivalent, N-hydroxysuccinimidyl ester α-end-functionalized PBA88 was ligated to CP 20 as a copper-free alternative to create the non-Janus conjugate PBA88-CP-PBA88 21 (Fig. 7a).

(a) Synthesis of the Janus conjugate PBA71-CP-PS68 19 obtained via a consecutive active ester/thiol-ene reactions and the non-Janus PBA88-CP-PBA88 conjugate (21) obtained via active ester chemistry. (b) Calcein dye leakage experiment using LUVs with 2 μM Janus conjugate 19. No dye leakage was observed for non-Janus conjugate 21 at 20 μM and DMSO at 2 vol%. (c) Schematic representation of the pore formation using Janus conjugate 19 showing sequestering of PS (in blue) forming the central macropore cavity and the PBA (in red) interacts with the phospholipid bilayer.

As shown in Fig. 7b on addition of the Janus conjugate 19, the calcein is released from the LUVs, which indicates pore formation. Further, despite the limited solubility of the Janus conjugate 19 in DMSO (0.1 mM), the addition to the calcein encapsulated LUVs showed ~10% calcein released (final concentration of Janus conjugate 19 is 2 μM). On the other hand, the non-Janus conjugate 21 did not cause calcein release from the LUVs at concentrations up to 20 μM.

Discussion

The conjugation of well-defined polymers to CPs has been established as a viable route to form NTs of defined length and functionality23,24. Two main routes have been employed to obtain CP–polymer NTs. The divergent route, whereby polymer chains are grown from the CP amino-acid side chains, can be achieved in a ‘graft-from’ procedure. For example, Couet et al.44,45 have employed this route to synthesize CP–polymer NTs from CPs bearing initiator side chains. Although the resulting CP–polymer NTs are uniform in length, it is difficult to assess the polymer molecular weight and uniformity as well as the overall polymer-grafting density on the CP45, and this strategy does not allow for the conjugation of two different polymer chains to the CP core. In contrast, the convergent approach is an elegant route for CP–polymer NT formation that allows control and assessment of each stage of the synthesis and self-assembly process. This approach requires the use of high yielding, site-specific conjugation chemistries to obtain well-defined conjugates. The combination of such efficient ligation protocols and controlled radical polymerization techniques (for example, RAFT polymerization)46 that lead to polymers with narrow molecular weight distributions and well-defined chain ends, provides access to targeted polymer-grafting densities on the CP core and some degree of control over NT length24,26. In addition, the conjugation of polymers to CP pre-assembly permits finer control over the organization process of the peptides into NTs24,25,26,27,28,29.

A two-step convergent strategy utilizing consecutive orthogonal conjugation reactions47 to attach two independently synthesized polymeric chains to the CP was used for the synthesis of the peptide–polymer conjugates described herein. Although a number of sequential orthogonal conjugation chemistries have been reported, including Diels-Alder/thiol-ene48, Diels-Alder/CuAAC48, ester-amide/thiol-ene49,50, and CuAAC/thiol-ene51, we have opted to employ conjugation chemistries that provide high-yielding conversions without necessitating the synthesis of complicated amino acids or linkers. RAFT polymerization, which enables the controlled polymerization of a wide range of monomers in very mild reaction conditions52,53, also allows us to introduce orthogonal handles that can facilitate ligation to CPs. For instance, our group has extensively utilized the CuAAC54,55 as a means to efficiently couple polymers with an α-terminated alkyne to CPs that have azidolysine side chains24,25. RAFT polymerization also provides polymeric chains with a thiocarbonyl thio group at their ω-chain end, which can be reduced to a thiol that can be utilized for conjugation via a photochemical thiol-ene51,56 addition reaction. To complement the ease of obtaining thiol-terminated polymers, the allyloxycarbonyl (Alloc) side chain-protecting group used in the synthesis of the CP provides the alkene functionality required for the photochemical thiol-ene reaction. Although the side chain Alloc-protecting group on L-lysine is traditionally employed as a protecting group that can be removed orthogonally to Boc, tert-butyl and trityl protection groups57, it is also a cheap and original handle as an alkene functionality readily available for the conjugation of a thiol-terminated polymer.

As shown in Table 1, well-defined PBA and PCHA polymers bearing the alkyne chain-end functionality and PS polymers bearing a thiol end-group with various degrees of polymerization ranging between 34 and 100 were synthesized and characterized by 1H-NMR and size exclusion chromatography (SEC). Notably, the use of RAFT polymerization allowed for the synthesis of polymer pairs (comprising PS and either PBA or PCHA) in which the difference in average degree of polymerization between the two polymer arms was within 8% (Table 2) to ultimately provide uniform hybrid CP–polymer conjugates.

Comparison of the glass transition temperatures of the polymers presented in Table 1 and the conjugates in Table 2 indicates that the Tg of the unconjugated polymers are notably different from those of the one-armed CP–polymer intermediates 3–7. Similarly, CuAAC of PBA or thiol-ene addition of PS to one-armed CP–polymer intermediates 3, 4, 8, 9, 10 that yielded two-armed CP–polymer conjugates 11–14 also causes a change in Tg corresponding to the individual polymer arms. This observation suggests that the coupling of polymers to the CPs affects the arrangement of the conjugates at temperatures below the glass transition. Although no quantification of polymer conjugation efficiency can be derived from the differences in Tg, this provides a qualitative indication for polymer coupling to the CP.

The self-assembly of CP–polymer conjugates into NTs has clearly been demonstrated in a number of studies where our group24,25,26,27,28,29 and others30,44,45,58 have successfully utilized numerous complementary techniques to characterize and visualize NTs composed of various types of polymeric coronas including hydrophilic and charged24 as well as hydrophobic polymers30,58. Because of the dynamic nature of the conjugate assemblies, we have found that NTs formed from individual conjugates tend to disaggregate when deposited on a substrate, therefore making it difficult to image unless the polymeric shell is crosslinked27,29 after assembly. Fortunately, DLS, FT-IR and small-angle neutron scattering, all of which are established experimental techniques that have been used to assess the association between CP moieties, enabled the NTs to be characterized.

Correlation of the FT-IR wavenumber corresponding to the N–H stretch with those of NH···O hydrogen bonds of known length59 gave NH···O distances for the CP, CP–polymer intermediates and conjugates of 2.97 Å, which is in agreement with hydrogen bonding distances in previously reported CP NTs14 and CP–polymer NTs24,30,45. The use of CDCl3 as a solvent results in 1H-NMR spectra in which the proton resonances derived from the CP moiety are suppressed because of the low mobility of the CP core after self-assembly60, whereas those of the polymers are still observed. This suppression of the proton resonances derived from the CP is analogous to the suppression of proton resonances from hydrophobic polymers that exhibit limited mobility in the core of block copolymer micelles when analysed in deuterated water61. This phenomenon provides an indication that the CP–polymer conjugates are forming NTs.

NMR spectroscopy was also used to assess the microstructure of the CP–polymer NTs. The distribution of the polymer chains conjugated to the CPs was assessed using 2D 1H–1H Nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) NMR, in which protons in close spatial correlation (<0.5 nm) undergo cross-relaxation62. 2D 1H–1H NOESY NMR is a powerful technique for the elucidation of Janus structures in solution that has been used for a variety of systems31,63,64,65. In this work, it is used to elucidate the Janus character of the CP–polymer NTs. The cross-relaxation of proton resonances from conjugates bearing a pair of immiscible polymers (PBA and PS, conjugates 11–14) is compared with those of CP–polymer NTs with pairs of polymers that are miscible (PCHA and PS, conjugates 15–17). The absence of cross-relaxation peaks in the 1H–1H NOESY NMR contour plot between PBA and the PS chains suggests that the protons on the two chains are separated by a distance greater than 0.5 nm, indicating the Janus character of the CP–polymer NTs as a result of microphase separation (demixing) of the polymer chains.

Polymer miscibility of the CP–polymer NTs was also assessed in bulk. The hybrid CP–polymer NTs possess similar temperature features to those of polymer blends comprising PCHA and PS42. Calculation of χN, whereby N is the average degree of polymerization for the two polymers coupled to the CP, demonstrates that the results obtained by NOESY NMR and DSC are in good agreement with polymer phase separation theory66. Indeed, miscible polymer combinations (for example, PCHA and PS) exhibit χN values that are below or at the critical point for homopolymer phase separation (χNc=2) and immiscible polymer combinations (for example, PBA and PS) exhibit χN values above the critical point for polymer phase separation (Table 2).

The conjugates presented in this contribution present unique structures with well-defined subnanometre pore and corona structures with a ‘mixed’ hybrid or ‘demixed’ Janus configuration. In comparison with the formation of Janus cylinders, which required the formation of a macrophase-separated film33,34 or the complex synthesis of brush-type polymers67, the modular self-assembly method proposed here offers a facile alternative for the formation of Janus NTs in solution.

Although non-modified CPs have been shown to assemble in lipid bilayers and function as artificial ion channels21, the ability to generate Janus NTs opens new avenues for the modulation of NT solubility, functionality and their properties as transbilayer pores. The ability of Janus NTs to form membrane pores is assessed using model LUVs. Assuming unilamellarity of the LUVs, complete mass recovery of the LUVs after purification and a NT length equal to the membrane thickness, calculations indicate that an average of 21 NTs of 19 are incorporated per LUV. Given the number of NTs per LUV and that the hydrodynamic size of calcein, calculated using the diffusion coefficient68 2.4 × 10−10 m2 s−1, exceeds the CP–polymer NT cavity size, we propose that the Janus NTs must assemble within the lipid bilayer by sequestering the PS chains to form a macropore. Self-assembly to form a macropore is likely as PS is immiscible with phospholipid chains and this ultimately permits the release of the calcein dye, which is too large to fit through the pore of a single NT (Fig. 7c). These results suggest that Janus NTs may open up new versatile strategies in designing transbilayer protein channel mimics through a bottom-up approach.

In conclusion, we have shown the first fabrication of Janus CP–polymer NTs in solution and in bulk via the spontaneous self-assembly of conjugates combining associative CPs with phase-separating polymers. These novel, supramolecular nano-objects have a unique structure, consisting of a subnanometre pore with a hybrid polymer corona whose phase separation can be controlled through the attachment of two immiscible polymers to a single CP core through the use of two efficient, convergent and orthogonal coupling strategies. In addition, we have also provided a pathway for the efficient synthesis and characterization of the CP–polymer conjugates and NTs, which is often hampered because of the tendency of the CP to form an extended hydrogen-bonded network. Through combined results from NMR, DLS and FT-IR, the resulting NTs were scrutinized from the macro-length scales down to the molecular level. The ability of the Janus NTs to form macropores in phospholipid bilayers via phase segregation was also demonstrated on LUVs. The self-assembly of hybrid CP–polymer conjugates provided here presents a viable and interesting bottom-up approach for the fabrication of new nanotubular materials that combine subnanometre pore dimensions with well-defined lengths and dual functionality induced by the ligation of two different polymers that form the corona of the NT.

Methods

Materials

DMF (HPLC grade, 99%) and 1,4-dioxane (99%) was purchased from Merck. Dichloromethane (CH2Cl2, 99%) tetrahydrofuran (99%), MgSO4 and TFA (peptide grade, 99%) were purchased from Ajax Finechem. Trifluoroethanol (98%), hydroquinone (98%), 2,2-dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone (99%), N-hydroxysuccinimide (98%), N-methylmorpholine (NMM; 99%), lithium bromide (99%), (+)-sodium ascorbate and Suba-Seal were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Methanol (99%) were purchased from Redox Chemicals. CuSO4·5H2O was purchased from APS Chemicals. Egg yolk phosphatidylcholine (EggPC) (>99%) and Avanti mini-extruder were purchased from AusPep Pty. Ltd. (Tullamarine, VIC, Australia). Fmoc-D-Leu-OH, Fmoc-L-Lys(Alloc)-OH, Fmoc-L-Lys-OH, Fmoc-L-Trp(Boc)-OH, O-benzotriazole-N,N,N ′,N ′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate, hydroxybenzotriazole were purchased from Novabiochem (Kilsyth, VIC, Australia) and were used as received. N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA, 99%), 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoroisopropanol (99%) and 2-chloro-4,6-dimethyl-1,3,5-triazine (97%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Castle Hill, NSW, Australia). Fmoc-L-Lys(N3)-OH (ref. 25) and 4-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium tetrafluoroborate (DMTMM·BF4; ref. 69) were prepared according to literature methods.

Peptide synthesis

The linear peptide (1), H2N-L-Trp(Boc)-D-Leu-L-Lys(N3)-D-Leu-L-Trp(Boc)-D-Leu-L-Lys(Alloc)-D-Leu-OH was synthesized using a 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin (400 mg, resin loading 1.01 mmol g−1) in a sinter-fitted syringe. Under an atmosphere of nitrogen, the resin was allowed to swell for 30 min using anhydrous CH2Cl2. The resin was drained and treated with a solution of Fmoc-D-Leu-OH (2.2 equiv. relative to resin capacity) and DIPEA (4 equiv. relative to amino acid) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 and agitated at room temperature for 2 h. Following draining of the resin, a mixture of CH2Cl2:DIPEA:methanol (7:1:2 v/v/v, 3 × 8 ml × 5 min) was added to the resin to cap any unreacted sites. The resin was washed with CH2Cl2 (5 × 8 ml), DMF (5 × 8 ml) and CH2Cl2 (5 × 8 ml) again, after which the resin was dried under reduced pressure. Fmoc deprotection of the resin-coupled amino acid was achieved by agitation of the resin in 20% piperidine in DMF (3 × 8 ml × 3 min) and then washed with DMF (5 × 8 ml), CH2Cl2 (5 × 8 ml) and DMF (5 × 8 ml). This provided the resin-bound free amino-terminal peptide, which was immediately coupled to the subsequent Fmoc amino acid. For a coupling reaction, the Fmoc amino acid (2.5 equiv. relative to loading), O-benzotriazole-N,N,N ′,N ′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (2.5 equiv. relative to loading) and DIPEA (8 equiv. relative to loading) was added to DMF (8 ml) and subsequently added to the resin. The coupling reaction was allowed to proceed at ambient temperature for 3 h and then drained and washed with DMF (5 × 8 ml). After completion of the amino acid-coupling reactions (Supplementary Fig. S9) and the removal of the final Fmoc protection group, the peptide was cleaved from the resin using a solution of 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoroisopropanol:CH2Cl2 (1:4 v/v, 3 × 8 ml × 10 min) and then washed with CH2Cl2 (3 × 8 ml). The combined washings were concentrated under reduced pressure to afford an off-white solid. Yield: 518 mg (91%). Purity was assessed by reverse-phase HPLC and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) confirmed the linear product. HRMS (electrospray ionization; ESI) [M+H]+ calculated: 1,409.8191, found: 1,409.8171.

Cyclization of linear peptide (1, 745 mg, 0.529 mmol) was achieved using 1.2 equiv. of coupling agent DMTMM BF4 (208 mg, 0.634 mmol) in anhydrous DMF (106 ml). The resulting mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 5 days (Supplementary Fig. S9). Subsequently, the volume of DMF was reduced under reduced pressure, and then the peptide was precipitated by addition of excess methanol and the resulting suspension was cooled in an ice bath, filtered and the solid washed with ice-cold methanol (10 ml) to yield Boc-protected CP as an off-white solid. Yield: 349 mg (47%). HRMS (ESI) [M+Na]+ calculated: 1,413.7905, found: 1,413.7863.

The Boc protection groups present on the tryptophan residues of the CP described above were removed through treatment with TFA:triisopropylsilane:thioanisole:water (85:5:5:5 v/v/v/v, 3 ml) for 3 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and then precipitated with cold diethyl ether and dried in vacuo to give CP 2 as an off-white product. 1H-NMR (500 MHz, TFA-d): 8.12 (d, 2H), 7.64 (d, 2H), 7.56 (s, 2H), 7.44–7.33 (m, 4H), 5.85 (m, 1H), 5.33 (d, 1H), 5.30 (d, 1H), 5.24 (t, 2H), 4.89–4.64 (m, 8H), 3.38–3.12 (overlapping m, 8H), 2.0–0.6 (m, 48H). 13C-NMR (125 MHz, TFA-d): 173.6, 172.0, 157.3, 135.2, 130.3, 125.7, 125.5, 124.3, 124.1, 121.9, 118.2, 117.1, 67.7, 65.9, 53.2, 52.9, 51.2, 42.0, 40.8, 32.7, 27.8, 24.6, 21.9, 21.4, 20.9, 20.0. HRMS (ESI) [M+Na]+ calculated: 1,213.6857, found: 1,213.6844.

Similar protocols were followed for the synthesis of CPs 18 and 20, which were made from the linear peptide precursors H2N-L-Lys(Alloc)-D-Leu-L-Trp(Boc)-D-Leu-L-Lys(Boc)-D-Leu-L-Trp(Boc)-D-Leu-OH and H2N-L-Lys(Boc)-D-Leu-L-Trp(Boc)-D-Leu-L-Lys(Boc)-D-Leu-L-Trp(Boc)-D-Leu-OH, respectively. The purity of the linear peptide precursors was confirmed by analytical reverse-phase HPLC-MS. Both products were obtained as white solids after cyclization with DMTMM BF4 and subsequently with Boc deprotection with TFA:triisopropylsilane:water (95:2.5:2.5 v/v/v) in good yields 320–350 mg (40–44%). CP 18 1H-NMR (500 MHz, TFA-d): 8.14 (d, 2H), 7.67 (d, 2H), 7.56 (s, 2H), 7.40–7.34 (m, 4H), 5.87 (m, 1H), 5.33 (d, 1H), 5.29 (d, 1H), 5.24 (t, 2H), 4.89–4.68 (m, 8H), 3.3–3.1 (overlapping m, 8H), 2.0–0.6 (m, 48H). 13C-NMR (125 MHz, TFA-d): 173.6, 172.0, 157.2, 135.3, 130.4, 125.8, 125.5, 124.3, 124.1, 121.9, 118.2, 117.0, 67.7, 65.9, 53.2, 52.9, 51.9, 42.1, 40.8, 32.7, 26.0, 24.5, 21.9, 21.3, 20.9, 19.9. MALDI-FTICR (M+Na+): calculated: 1187.6969, found: 1187.6952. CP 20 1H-NMR (500 MHz, TFA-d): 8.21 (d, 2H), 7.74 (d, 2H), 7.63 (s, 2H), 7.48–7.42 (m, 4H), 5.32 (t, 2H), 4.89–4.78 (m, 6H), 3.39–3.23 (overlapping m, 8H), 2.0–0.6 (m, 48 H). 13C-NMR (125 MHz, TFA-d): 173.6, 172.0, 157.2, 135.3, 125.8, 124.0, 118.8, 116.9, 53.2, 52.6, 51.9, 42.2, 40.7, 32.7, 26.0 24.5, 21.8, 21.3, 19.9. HRMS (MALDI-FTICR) (M+Na+): calculated: 1,103.6740, found: 1,103.6746.

Synthesis of NHS-PABTC chain transfer agent

The (N-hydroxysuccinimidyl ester propanoate)yl butyl trithiocarbonate chain transfer agent (NHS-PABTC) was prepared from PABTC using a protocol adapted from the synthesis of PYPBTC as described above. PABTC (5 g, 21 mmol) was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (100 ml) and stirred followed by the addition of N-hydroxysuccinimide (1.2 equiv., 2.9 g, 25.2 mmol) and DMAP (0.25 g, 2.1 mmol). To this mixture, 50 ml CH2Cl2 solution containing 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) (1.2 equiv., 4.83 g, 25.2 mmol) was added slowly over a period of 50 min at room temperature (Supplementary Fig. S10). The reaction was allowed to proceed at room temperature for a further 16 h yielding an orange solution. The excess EDC and DMAP was removed by washing twofold with water (200 ml) and twofold with brine (200 ml). The CH2Cl2 phase containing the product was dried over an excess MgSO4, filtered and dried to ~7 ml via rotary evaporation. Flash silica chromatography was performed using hexane:ethyl acetate (1:1 v/v) as the eluent. The purified NHS-PABTC was isolated as a yellow oil and determined pure by TLC (Rf=0.52) and 1H-NMR analysis. Yield: 80% (5.6 g, 16.7 mmol). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ p.p.m.: 5.12 (q, 1H, S-CH(-CH3)-CO-), 3.38 (t, 2H, S-CH2-CH2-), 2.83 (s, 4H, N-hydroxysuccinimidyl–CH2-CH2-), 1.72 (d, 3H, -CH(CH3)-S-), 1.63 (quintet, 2H, S-CH2-CH2-CH2-), 1.43 (quintet, 2H, -CH2-CH2-CH3), 0.93 (t, 3H, -CH2-CH3). 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 75.5 MHz) δ p.p.m.: 220.2 (-S-C(=S)-S-), 168.9 (succinimide C=O), 167.2 (-CH(CH3)-C(=O)-O-N), 47.5 (-CH(CH3)-S), 37.2 (-S-CH2-CH2), 25.6 (succinimide 2 × CH2), 22.0 (-CH2-CH2-CH3), 16.6 (-CH(CH3)-S-), 13.6 (-CH2-CH3). HRMS (ESI) (M+Na+): calculated: 358.0211, found: 358.0213.

Polymerizations

RAFT polymerization of n-butyl acrylate, cyclohexyl acrylate and styrene is described in the Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Figs S11–S13.

Conjugation of polymers to CP

CuAAC of alkyne-terminated polymers to CP was adapted from Poon et al.26 Typically, 15 mg of CP (12.5 μmol) or 40 mg of CP–polymer intermediate (6.9 μmol for CP–PBA36 intermediate) was added to a microwave reaction borosilicate tube (CEM Corp.). To the tube containing CP, a mixture of DMF (0.5 ml) and trifluoroethanol (0.5 ml) was added followed by 10 min of sonication to aid solvation. To the reaction tube containing one-armed CP–polymer intermediate, DMF (1 ml) was added followed by sonication for 5 min to aid solvation. In a separate 20 ml vial, alkyne-terminated PBA36, PBA71, PCHA34 or PCHA63 (1.05 equiv., 13.1 μmol relative to 12.5 μmol CP) was dissolved in DMF (2 ml) and added to the microwave reaction tube containing the CP or CP–PS intermediate. For PCHA97, polymer (1.05 equiv., 13.1 μmol relative to 12.5 μmol of CP) was dissolved in DMF (2 ml) and subsequently added to the microwave reaction tube. CuSO4·5H2O (4 equiv., 12.5 mg, 0.05 mmol) and sodium ascorbate (8 equiv., 20 mg, 0.1 mmol) were added to the microwave reaction vial and sonicated to aid dissolution of the compounds. The sample was irradiated in a microwave reactor (CEM Corp. S-class Discover) operating at 100 °C for 20 min using a powermax (200 W) microwave protocol. For the reaction mixture containing the CP and PCHA97 in a mixture of DMF and dioxane, the microwave reactor was programmed to operate at 85 °C for 30 min. After completion of the microwave protocol, the reaction tube was cooled with a stream of nitrogen gas and the reaction mixture was subsequently precipitated in a mixture of ice-cold EDTA solution (65 mM, pH 8.5) and isolated via centrifugation at 14,000 r.p.m. (17,123 g). To remove the EDTA, the CP–polymer conjugate sample was suspended in DMF and washed with ice-cold water and isolated via centrifugation at 14,000 r.p.m. (17,123 g) for 5–10 min. The supernatant was decanted and the CP–polymer intermediate was dissolved in CH2Cl2 and dried over MgSO4 to yield a light brown solid.

Thiol-ene addition was performed on 15 mg of CP (12.5 μmol) or 40 mg of CP–polymer intermediate (6.9 μmol for CP–PBA36 intermediate) in a 20-ml vial. DMF (3 ml) was added to the vial and the reaction was sonicated to aid dissolution of the CP or CP–polymer intermediate. Aminolysed PS (1.05 equiv. 13.1 μmol relative to 12.5 μmol CP) and 2,2-dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone (1 equiv., 12.5 μmol relative to 12.5 μmol CP) were added to the solution containing the CP or CP–polymer intermediate. The 20-ml vial was sealed using a Suba-Seal and the solution was degassed on ice for 15 min, and then put under the ultraviolet lamp (365 nm, 6 W) for 24 h. The reaction mixture was precipitated into ice-cold methanol:water solution (9:1 v/v) and centrifuged at 14,000 r.p.m. (17,123 g) for 15 min. The supernatant was decanted and the CP–polymer intermediate or CP–polymer conjugate was isolated. Analysis of the intermediate and the CP–polymer conjugate was assessed by 1H-NMR in a TFA:CDCl3 mixture (1:1 v/v). To assess the conversion of the thiol-ene addition, the disappearance of the vinyl resonance at 5.8 p.p.m. was integrated versus the proton resonance of tryptophan at 7.6 p.p.m. or against the α-carbon proton resonance at 4.55 p.p.m. where applicable (Supplementary Fig. S2). Yield: 30–60%. Conversions of thiol-ene reaction are reported in Table 2.

Succinimidyl ester PBA conjugation to amine-functionalized CP 18 (20 mg, 17.2 μmol) or 20 (20 mg, 18.5 μmol) was achieved in DMF (3 ml) with PBA71 (234 mg, 1.5 equiv.) or PBA88 (625 mg, 3 equiv.) polymer, respectively. NMM (6 equiv.) was added to the reaction mixture and it was left to stir at room temperature for 16–24 h. After the reaction, the excess polymer was removed through size exclusion using a column of biobeads S-X in tetrahydrofuran (38 × 4.5 cm2). The isolated polymer was dried through rotary evaporation.

Preparation of the LUVs

EggPC (10 mg, 12.9 μmol) was dissolved in chloroform (50 ml) in a round-bottom flask and the solvent was removed by slow rotary evaporation to yield a uniform and dry lipid film. The film was hydrated with 1.0 ml phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4) containing calcein (40 mM) for 1–2 h and placed in an ultrasonic bath for 30 s. The solution containing lipids was then subjected to five freeze-thaw cycles and was then extruded 29 times through a 0.1-μm pore size polycarbonate membrane using the Avanti mini-extruder kit to yield LUVs. Unencapsulated calcein was removed by SEC over a Sephadex G-200 column (25 × 4.0 cm2) using phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4) as the eluent. Average LUV size was measured by DLS to be 110 nm in hydrodynamic diameter.

Characterization methods

DSC was performed on a Mettler-Toledo DSC 823e connected to a dewar containing liquid nitrogen and continuously purged with 50 ml min−1 N2 gas throughout the analysis. All samples (5–10 mg) were hermetically sealed in a 40-μl aluminium pan and measured against an empty pan used as a reference. All samples were heated 50 °C above the highest expected Tg to remove thermal history followed by two subsequent cooling and heating cycles. Heating and cooling rates was kept constant at 10 °C min−1 with 10 min isothermal intervals between heating and cooling cycles.

SEC was performed on a Polymer Laboratories PL-GPC 50 equipped with a PL-ASRT autosampler and differential refractive index detector using DMF containing 0.04 g l−1 hydroquinone and 0.1% LiBr as the mobile phase. Analyses of samples (2–3 mg ml−1) were run over PolarGel columns at 50° at 0.7 ml min−1. The molecular weights of the polymers are reported relative to a conventional calibration that consists of PS standards ranging from 0.682 to 1,670 kg mol−1. For analysis of the aminolysed PS polymers compared with the non-aminolysed PS, samples (3–4 mg ml−1) were run at 1 ml min−1 at 40 °C on a Shimadzu module system equipped with a PLgel guard column, PLgel mixed-B (10 μm, 300 × 7.5 mm2) and PLgel mixed-C (5 μm, 300 × 7.5 mm2) columns, an SIL 10ADVP autoinjector, an RID 10A DRI detector and a SPD-10AVP ultraviolet detector operating at 315 nm.

2D 1H–1H NOESY NMR was performed on a Bruker Avance 500 MHz NMR spectrometer operating at 300 K. For each experiment, a 90° pulse calibration and the proton relaxation time for each sample was determined. Using the ‘nmrgrnoesy’ parameter set on the TopSpin software, a mixing time of 500 ms, with sweep width set at 9 p.p.m. and a spectral centre (o1p) set at 4.5 p.p.m. was used. The number of scans was set to 16 scans over 1,024 × 256 scans and the resulting 2D spectrum was calibrated to CDCl3 using the TopSpin software.

FT-IR was performed on a Bruker ALPHA-E ATR FT-IR spectrometer equipped with a ZnSe crystal. For each sample, an average from 64 scans was recorded and background corrected.

DLS measurements were performed on a Malvern ZetaSizer Nano S equipped with a 633-nm laser and a detector at 173° backscattering angle operating at 20 °C. DLS of all samples were measured using 1.5 mg ml−1 of the CP–polymer intermediate or 1.0 mg ml−1 of the CP–polymer conjugate. The refractive indices (nD) and viscosity (η) for chloroform (nD=1.490, η=0.563 cP) or tetrahydrofuran (nD=1.407, η=0.4854 cP) were used for the determination of the particle size distributions. Particle size distributions were analysed using the intensity distribution using the ‘general purpose–normal resolution’ mode in the Zetasizer software (v 6.32).

Time-dependent fluorescence spectroscopy was performed using a Perkin-Elmer LS50B luminescence spectrometer at 20 °C. Calcein encapsulated LUVs (2 ml, 0.1 mg ml−1, 0.13 mM) was pipetted into a disposable poly(methyl methacrylate) fluorescence cuvette. The excitation wavelength was set at 493 nm and the emission wavelength was set at 505 nm, with both excitation and emission slits set at 2.5 nm. The emission of the baseline at 505 nm was monitored for 70 s followed by the addition of the conjugate sample (40 μl of 0.1 mM containing Janus conjugate 19 or 40 μl of 1 mM containing non-Janus conjugate 21). At 300 s, Triton X100 (40 ml, 10% w/v in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) was added to the cuvette. Calcein dye leakage, Δf (in %) was determined with the following equation:

where fs is the fluorescence signal at 290 s after addition of the sample, fb is the fluorescence signal of the baseline before the addition of the sample at 40 s and fT is the fluorescence signal after the addition of the Triton X100 at 400 s.

A calculation was made to determine the number of CP–polymer NTs per LUV. The calculation assumes that (i) the vesicles are uniform and unilamellar throughout, (ii) there is 100% recovery of the LUVs obtained after the sephadex G-200 column, which was used to remove unencapsulated calcein dye and (iii) the length of the CP–polymer NT, when partitioned in the lipid bilayer, is equal to the thickness of the bilayer (3.7 nm). The number of lipid molecules per LUV was calculated as follows:

where r is the LUV hydrodynamic radius as measured by DLS (55 nm), h is the thickness of the phophatidylcholine bilayer (3.7 nm) (ref. 70) and a is the surface area of the phosphatidylcholine head group (0.74 nm2) (ref. 70) on the outside of the LUV. The number of LUVs, NLUV in a single 2 ml fluorescence sample was calculated according to:

where the [lipid] is described in molar (0.13 mM) and NA is Avogadro’s number. Similarly, the number of CP–polymer NTs, NCPNT in a 2.04-ml sample was determined through the following expression:

where the [sample] is described in molar (1.96 μM) for Janus conjugate PBA71-CP-PS68 19 and NCP/NT is the number of CP–polymer conjugates per NT assuming an equal spacing of 0.594 nm between CP units as determined by the N–H…O spacing (0.297 nm) obtained from the FT-IR data. In addition, the volume change has been accounted for by the addition of the 40-μl sample to the 2-ml solution containing the LUVs. For this calculation, assumption (iii), where the NT assumes the thickness of the lipid bilayer, was implemented. The ratio NCPNT/NLUV describes the number of CP–polymer NTs per LUV.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Danial, M. et al. Janus cyclic peptide–polymer nanotubes. Nat. Commun. 4:2780 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3780 (2013).

References

Whitesides, G. M. & Grzybowski, B. Self-assembly at all scales. Science 295, 2418–2421 (2002).

Aida, T., Meijer, E. W. & Stupp, S. I. Functional supramolecular polymers. Science 335, 813–817 (2012).

Percec, V. et al. Self-assembly of Janus dendrimers into uniform dendrimersomes and other complex architectures. Science 328, 1009–1014 (2010).

Mann, S. Self-assembly and transformation of hybrid nano-objects and nanostructures under equilibrium and non-equilibrium conditions. Nat. Mater. 8, 781–792 (2009).

Kostiainen, M. A., Kasyutich, O., Cornelissen, J. J. L. M. & Nolte, R. J. M. Self-assembly and optically triggered disassembly of hierarchical dendron–virus complexes. Nat. Chem. 2, 394–399 (2010).

Duncan, R. & Gaspar, R. Nanomedicine(s) under the microscope. Mol. Pharm. 8, 2101–2141 (2011).

Hsieh, W.-H., Chang, S.-F., Chen, H.-M., Chen, J.-H. & Liaw, J. Oral gene delivery with cyclo-(D-Trp-Tyr) peptide nanotubes. Mol. Pharm. 9, 1231–1249 (2012).

Motesharei, K. & Ghadiri, M. R. Diffusion-limited size-selective ion sensing based on SAM-supported peptide nanotubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 11306–11312 (1997).

Chen, R. J. et al. Noncovalent functionalization of carbon nanotubes for highly specific electronic biosensors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 4984–4989 (2003).

Xu, T. et al. Subnanometer porous thin films by the co-assembly of nanotube subunits and block copolymers. ACS Nano 5, 1376–1384 (2011).

Horne, W. S., Ashkenasy, N. & Ghadiri, M. R. Modulating charge transfer through cyclic D,L-alpha-peptide self-assembly. Chem.-Eur. J. 11, 1137–1144 (2005).

Tasis, D., Tagmatarchis, N., Bianco, A. & Prato, M. Chemistry of carbon nanotubes. Chem. Rev. 106, 1105–1136 (2006).

Tenne, R. & Redlich, M. Recent progress in the research of inorganic fullerene-like nanoparticles and inorganic nanotubes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 1423–1434 (2010).

Ghadiri, M. R., Granja, J. R., Milligan, R. A., McRee, D. E. & Khazanovich, N. Self-assembling organic nanotubes based on a cyclic peptide architecture. Nature 366, 324–327 (1993).

Chapman, R., Danial, M., Koh, M. L., Jolliffe, K. A. & Perrier, S. Design and properties of functional nanotubes from the self-assembly of cyclic peptide templates. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 6023–6041 (2012).

De Santis, P., Morosetti, S. & Rizzo, R. Conformational analysis of regular enantiomeric sequences. Macromolecules 7, 52–58 (1974).

Suga, T., Osada, S. & Kodama, H. Formation of ion-selective channel using cyclic tetrapeptides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 20, 42–46 (2012).

Granja, J. R. & Ghadiri, M. R. Channel-mediated transport of glucose across lipid bilayers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 10785–10786 (1994).

Khazanovich, N., Granja, J. R., McRee, D. E., Milligan, R. A. & Ghadiri, M. R. Nanoscale tubular ensembles with specified internal diameters—design of a self-assembled nanotube with a 13-Å pore. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 6011–6012 (1994).

Ghadiri, M. R., Kobayashi, K., Granja, J. R., Chadha, R. K. & McRee, D. E. The structural and thermodynamic basis for the formation of self-assembled peptide nanotubes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 34, 93–95 (1995).

Ghadiri, M. R., Granja, J. R. & Buehler, L. K. Artificial transmembrane ion channels from self-assembling peptide nanotubes. Nature 369, 301–304 (1994).

Fernandez-Lopez, S. et al. Antibacterial agents based on the cyclic D,L-α-peptide architecture. Nature 412, 452–455 (2001).

Couet, J. & Biesalski, M. Polymer-wrapped peptide nanotubes: peptide-grafted polymer mass impacts length and diameter. Small 4, 1008–1016 (2008).

Chapman, R., Jolliffe, K. A. & Perrier, S. Modular design for the controlled production of polymeric nanotubes from polymer/peptide conjugates. Polym. Chem. 2, 1956–1963 (2011).

Chapman, R., Jolliffe, K. A. & Perrier, S. Synthesis of self-assembling cyclic peptide-polymer conjugates using click chemistry. Aust. J. Chem. 63, 1169–1172 (2010).

Poon, C. K., Chapman, R., Jolliffe, K. A. & Perrier, S. Pushing the limits of copper mediated azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) to conjugate polymeric chains to cyclic peptides. Polym. Chem. 3, 1820–1826 (2012).

Chapman, R., Jolliffe, K. A. & Perrier, S. Multi-shell soft nanotubes from cyclic peptide templates. Adv. Mater. 25, 1170–1172 (2013).

Chapman, R., Warr, G. G., Perrier, S. & Jolliffe, K. A. Water-soluble and pH-responsive polymeric nanotubes from cyclic peptide templates. Chem. Eur. J. 19, 1955–1961 (2013).

Chapman, R., Koh, M. L., Warr, G. G., Jolliffe, K. A. & Perrier, S. Structure elucidation and control of cyclic peptide-derived nanotube assemblies in solution. Chem. Sci. 4, 2581–2589 (2013).

ten Cate, M. G. J., Severin, N. & Börner, H. G. Self-assembling peptide-polymer conjugates comprising (D-alt-L)-cyclopeptides as aggregator domains. Macromolecules 39, 7831–7838 (2006).

Voets, I. K. et al. Double-faced micelles from water-soluble polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 6673–6676 (2006).

Walther, A., André, X., Drechsler, M., Abetz, V. & Müller, A. H. E. Janus discs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 6187–6198 (2007).

Walther, A. et al. Self-assembly of janus cylinders into hierarchical superstructures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 4720–4728 (2009).

Ruhland, T. M., Gröschel, A. H., Walther, A. & Müller, A. H. E. Janus cylinders at liquid-liquid interfaces. Langmuir 27, 9807–9814 (2011).

Erhardt, R. et al. Janus micelles. Macromolecules 34, 1069–1075 (2001).

Konkolewicz, D., Gray-Weale, A. & Perrier, S. Hyperbranched polymers by thiol−yne chemistry: from small molecules to functional polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 18075–18077 (2009).

Barbey, R. & Perrier, S. A facile route to functional hyperbranched polymers by combining reversible addition−fragmentation chain transfer polymerization, thiol−yne chemistry, and postpolymerization modification strategies. ACS Macro Lett. 2, 366–370 (2013).

Flory, P. J. Principles of Polymer Chemistry Cornell Univ. Press (1953).

Fedors, R. F. A method for estimating both the solubility parameters and molar volumes of liquids. Polym. Eng. Sci. 14, 147–154 (1974).

Miwa, Y. et al. Direct detection of effective glass transitions in miscible polymer blends by temperature-modulated differential scanning calorimetry. Macromolecules 38, 2355–2361 (2005).

Siol, W. Polymer compatibility—a consequence of repulsive groups within monomer units. Makromol. Chem. Macromol. Symp. 44, 47–59 (1991).

Miwa, Y. et al. An ESR spin-label study on molecular mobility in the interface between microphases of a diblock copolymer: Effects of admixture of homopolymers that are miscible with one of the blocks. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 4073–4082 (2006).

Knöpfel, M., Smith, C. & Solioz, M. ATP-driven copper transport across the intestinal brush border membrane. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 330, 645–652 (2005).

Couet, J. et al. Peptide-polymer hybrid nanotubes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 3297–3301 (2005).

Couet, J. & Biesalski, M. Surface-initiated ATRP of N-isopropylacrylamide from initiator-modified self-assembled peptide nanotubes. Macromolecules 39, 7258–7268 (2006).

Chiefari, J. et al. Living free-radical polymerization by reversible addition—Fragmentation chain transfer: The RAFT process. Macromolecules 31, 5559–5562 (1998).

Barner-Kowollik, C. et al. ‘Clicking’ polymers or just efficient linking: what is the difference? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 60–62 (2011).

Williams, R. J., Barker, I. A., O'Reilly, R. K. & Dove, A. P. Orthogonal modification of norbornene-functional degradable polymers. ACS Macro Lett. 1, 1285–1290 (2012).

Singha, N. K., Gibson, M. I., Koiry, B. P., Danial, M. & Klok, H. A. Side-chain peptide-synthetic polymer conjugates via tandem ‘ester-amide/thiol-ene’ post-polymerization modification of poly(pentafluorophenyl methacrylate) obtained using ATRP. Biomacromolecules 12, 2908–2913 (2011).

Danial, M., Root, M. J. & Klok, H. A. Polyvalent side chain peptide-synthetic polymer conjugates as HIV-1 entry inhibitors. Biomacromolecules 13, 1438–1447 (2012).

Campos, L. M. et al. Development of thermal and photochemical strategies for thiol−ene click polymer functionalization. Macromolecules 41, 7063–7070 (2008).

Moad, G., Rizzardo, E. & Thang, S. H. Living radical polymerization by the RAFT process a third update. Aust. J. Chem. 65, 985–1076 (2012).

Perrier, S. & Takolpuckdee, P. Macromolecular design via reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT)/xanthates (MADIX) polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. 43, 5347–5393 (2005).

Tornøe, C. W., Christensen, C. & Meldal, M. Peptidotriazoles on solid phase: [1,2,3]-Triazoles by regiospecific copper(I)-catalyzed 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions of terminal alkynes to azides. J. Org. Chem. 67, 3057–3064 (2002).

Rostovtsev, V. V., Green, L. G., Fokin, V. V. & Sharpless, K. B. A stepwise huisgen cycloaddition process: Copper(I)-catalyzed regioselective ‘ligation’ of azides and terminal alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 2596–2599 (2002).

Hoyle, C. E. & Bowman, C. N. Thiol-ene click chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 1540–1573 (2010).

Mellor, S. L. et al. Fmoc Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis Oxford Univ. Press (2000).

Loschonsky, S., Couet, J. & Biesalski, M. Synthesis of peptide/polymer conjugates by solution ATRP of butylacrylate using an initiator-modified cyclic D-alt-L-peptide. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 29, 309–315 (2008).

Lautié, A., Froment, F. & Novak, A. Relationship between NH stretching frequencies and N…O distances of crystals containing NH…O hydrogen bonds. Spectrosc. Lett. 9, 289–299 (1976).

Nakamura, K., Endo, R. & Takeda, M. Study of molecular motion of block copolymers in solution by high resolution proton magnetic resonance. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Phys. Ed. 15, 2095–2101 (1977).

Kwon, G. et al. Micelles based on AB block copolymers of poly(ethylene oxide) and poly(β-benzyl L-aspartate). Langmuir 9, 945–949 (1993).

Mo, H. & Pochapsky, T. C. Intermolecular interactions characterized by nuclear Overhauser effects. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 30, 1–38 (1997).

Pradhan, S., Brown, L. E., Konopelski, J. P. & Chen, S. Janus nanoparticles: Reaction dynamics and NOESY characterization. J. Nanopart. Res. 11, 1895–1903 (2009).

Liu, X., Yu, M., Kim, H., Mameli, M. & Stellacci, F. Determination of monolayer-protected gold nanoparticle ligand-shell morphology using NMR. Nat. Commun. 3, 1182 (2012).

Du, J. & Armes, S. P. Patchy multi-compartment micelles are formed by direct dissolution of an ABC triblock copolymer in water. Soft Matter 6, 4851–4857 (2010).

Bates, F. S. Polymer-polymer phase behavior. Science 251, 898–905 (1991).

Huang, K. & Rzayev, J. Charge and size selective molecular transport by amphiphilic organic nanotubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 16726–16729 (2011).

Harrison, D. J., Manz, A., Fan, Z., Lüdi, H. & Widmer, H. M. Capillary electrophoresis and sample injection systems integrated on a planar glass chip. Anal. Chem. 64, 1926–1932 (1992).

Raw, S. A. An improved process for the synthesis of DMTMM-based coupling reagents. Tetrahedron Lett. 50, 946–948 (2009).

Huang, C. & Mason, J. T. Geometric packing constraints in egg phosphatidylcholine vesicles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 75, 308–310 (1978).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Australian Research Council Discovery (K.A.J. and S.P.) and Future Fellowship (S.P.) Programmes for funding. We thank Dr. Ian Luck (University of Sydney) for assistance with NMR spectroscopy. We thank Algi Serelis from DuluxGroup for provision of the (propanoic acid)yl butyl trithiocarbonate chain transfer agent; Derrick Roberts and Dr. Guillaume Gody (University of Sydney) for proofreading this manuscript; Ming Liang Koh (University of Sydney) and Dr. Kathleen Wood (Bragg Institute, Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation) for help with acquiring and fitting of the small-angle neutron scattering data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.D., S.P. and K.A.J. contributed to the design of the experiments, the synthesis and to the analysis of the data; M.D., S.P. and K.A.J. co-wrote the paper. P.G.Y. and C.M.-N.T. contributed to the preparation of the cyclic peptides and the development of the large unilamellar vesicle assay, respectively. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S13, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 917 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Danial, M., My-Nhi Tran, C., Young, P. et al. Janus cyclic peptide–polymer nanotubes. Nat Commun 4, 2780 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3780

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3780

This article is cited by

-

Supramolecular fibrillation of peptide amphiphiles induces environmental responses in aqueous droplets

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Straightforward preparation of supramolecular Janus nanorods by hydrogen bonding of end-functionalized polymers

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Dual self-assembly of supramolecular peptide nanotubes to provide stabilisation in water

Nature Communications (2019)

-

Designable and dynamic single-walled stiff nanotubes assembled from sequence-defined peptoids

Nature Communications (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.