Abstract

Histologic subclassification of high-grade endometrial carcinomas can sometimes be a diagnostic challenge when based on histomorphology alone. Here we utilized immunohistochemical markers to determine the immunophenotype in histologically ambiguous high-grade endometrial carcinomas that were initially diagnosed as pure or mixed high-grade endometrioid carcinoma, aiming to determine the utility of selected immunohistochemical panel in accurate classification of these distinct tumor types, while correlating these findings with the clinical outcome. A total of 43 high-grade endometrial carcinoma cases initially classified as pure high-grade endometrioid carcinoma (n=32), mixed high-grade endometrioid carcinoma/serous carcinoma (n=9) and mixed high-grade endometrioid carcinoma/clear cell carcinoma (n=2) were retrospectively stained with a panel of immunostains, including antibodies for p53, p16, estrogen receptor, and mammaglobin. Clinical follow-up data were obtained, and stage-to-stage disease outcomes were compared for different tumor types. Based on aberrant staining for p53 and p16, 17/43 (40%) of the high-grade endometrial carcinoma cases initially diagnosed as high-grade endometrioid carcinoma were re-classified as serous carcinoma. All 17 cases showed negative staining for mammaglobin, while estrogen receptor was positive in only 6 (35%) cases. The remaining 26 cases of high-grade endometrioid carcinoma showed wild-type staining for p53 in 25 (96%) cases, patchy staining for p16 in 20 (77%) cases, and were positive for mammaglobin and estrogen receptor in 8 (31%) and 19 (73%) cases, respectively, thus the initial diagnosis of high-grade endometrioid carcinoma was confirmed in these cases. In addition, the patients with re-classified serous carcinoma had advanced clinical stages at diagnosis and poorer overall survival on clinical follow-up compared to that of the remaining 26 high-grade endometrioid carcinoma cases. These results indicate that selected immunohistochemical panel, including p53, p16, and mammaglobin can be helpful in reaching accurate diagnosis in cases of histomorphologically ambiguous endometrial carcinomas, and can assist in providing guidance for appropriate therapeutic options for the patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-grade endometrial carcinomas are a group of diverse and often diagnostically challenging tumors, which include high-grade endometrioid carcinoma (FIGO grade 3), uterine serous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma and undifferentiated carcinoma.1 High-grade endometrioid carcinoma and serous carcinoma account for the majority of high-grade endometrial carcinomas, while they are associated with different molecular tumorigenesis and clinical outcomes. Previous study reported that the molecular profile of high-grade endometrioid carcinoma is between that of low-grade endometrioid carcinoma and serous carcinoma.2 Low-grade endometrioid carcinomas are generally classified as type I endometrial carcinomas, which are associated with prolonged unopposed estrogen stimulation, and usually have a favorable prognosis.3, 4 In contrast, serous carcinomas are classified as type II endometrial carcinomas which are not particularly estrogen dependent, and have poorer prognosis.4, 5 Serous carcinomas represent about 10% of all endometrial cancers, but account for a disproportionally high number (~40%) of endometrial cancer deaths.6 The analysis of clinical outcomes of high-grade endometrioid carcinoma has shown conflicting results. Many studies have shown that high-grade endometrioid carcinoma has a better overall survival rate compared to that of serous carcinoma,7, 8 whereas others reported that high-grade endometrioid carcinoma behaves similar to serous carcinoma.9, 10 High-grade endometrioid carcinoma primarily metastasizes to regional lymph nodes, and the metastasis is generally correlated with deep myometrial invasion. In contrast, metastasis of serous carcinoma can frequently extend to adnexal structures and peritoneum, and does not show significant association with the depth of myometrial invasion.1 Due to the high rate of metastasis even in the absence of myometrial invasion, comprehensive surgical staging is recommended when feasible in all women diagnosed with serous carcinoma,11 thus prompting more aggressive therapeutic modalities.

Morphologically, serous carcinoma can be sometimes difficult to distinguish from high-grade endometrioid carcinoma. A subset of serous carcinoma can exhibit ambiguous histomorphology with predominant glandular architectural pattern, with or without papillary growth.12, 13 Besides, endometrioid carcinoma can sometimes display a papillary architecture with intermediate nuclear atypia which can be mistaken for serous carcinoma.14, 15 In addition, both high-grade endometrioid carcinoma and serous carcinoma can show solid areas, making it more difficult to differentiate between the two. Furthermore, serous carcinoma may rarely demonstrate a background of endometrial hyperplasia which could suggest a mixed endometrioid and serous differentiation.16, 17, 18 The important question remains whether a subset of high-grade endometrial carcinomas diagnosed as high-grade endometrioid carcinoma actually represents serous carcinoma with endometrioid-like architectural pattern. Many studies have reported a poor inter-observer variability in the diagnosis of endometrial carcinomas, especially high-grade endometrioid carcinoma and serous carcinoma among non-subspecialized pathologists or even among gynecologic pathologists.16, 19, 20, 21 Therefore, the need for an accurate sub-classification of high-grade endometrial carcinomas is crucial as serous carcinoma require comprehensive surgical staging and more aggressive treatment.11, 22

While the p53 overexpression has been shown to correlate with serous carcinoma,23, 24 the absence of p53 staining does not entirely exclude serous carcinoma, as the p53 protein may be truncated due to frame-shift mutation leading to null p53 immunostaining.25 Furthermore, the aberrant p53 immunoreactivity has also been reported in up to 37% of high-grade endometrioid carcinoma.2, 13 Alternatively, the utilization of p53 along with p16 may increase the sensitivity of accurate identification of serous immunophenotype.26 However, rarely the high-grade endometrioid carcinoma may also show variable aberrant immunoreactivity for both p53 and p16.

The utilization of sensitive immunohistochemical markers such as p53 and p16 combined with other more specific tumor markers can assist in more accurate differentiation of serous carcinoma from high-grade endometrioid carcinoma.27 It was reported in a previous study that mammaglobin can be detected in majority of high-grade endometrioid carcinoma while being largely negative in uterine serous carcinoma,28 which suggested that mammaglobin may be a promising adjunctive marker to differentiate serous carcinoma from high-grade endometrioid carcinoma. In the present study, we retrospectively evaluated the expression of p53, p16, mammaglobin protein and estrogen receptor in high-grade endometrial carcinoma cases initially diagnosed as high-grade endometrioid carcinoma, and correlated the histomorphologic features and immunoprofiles of these tumors with patients’ clinical outcomes, to determine whether a subset of serous carcinomas with ambiguous histomorphology were underdiagnosed.

Materials and methods

Case Selection

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Kentucky Medical Center. A total of 43 hysterectomy specimens from patients with diagnosis of high-grade endometrial carcinoma from January 1999 to December 2003 were retrieved from the archives of the Department of Pathology at University of Kentucky Medical Center. These cases were initially diagnosed as pure high-grade endometrioid carcinoma (n=32), mixed high-grade endometrioid carcinoma/serous carcinoma (n=9) and mixed high-grade endometrioid carcinoma/clear cell carcinoma (n=2) based on histomorphology alone. All cases were independently reviewed by two gynecologic pathologists (MLC and RGK), and a representative section was selected for a panel of immunostains, including p53, p16, estrogen receptor, and mammaglobin.

Clinical Data

The retrospective study was done in accordance with the Institutional Review Board guidelines. The clinical follow-up information was obtained from Tumor Registry (mean follow-up interval 41 months), and the clinical outcomes were compared for stage to stage disease in different subtypes of endometrial cancer. The mean age of the patients was 64.5 years (ranged from 40 to 85 years).

Immunohistochemical Studies

Representative formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were stained with antibodies against p53 (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA; clone DO-7, 1:75 dilution), p16 (NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA; clone 16P07; pre-diluted), estrogen receptor (NeoMarkers; clone 1D5, 1:20 dilution), and mammaglobin (Zeta Corporation, Sierra Madre, CA; clone 31-A5; 1:50 dilution). The immunostaining was performed using manufacturer’s protocol for immunophenotypic markers with appropriate positive and negative controls. Briefly, antigen retrieval was performed at pH 9 using the PT-LINK system (Dako). Staining was performed utilizing EnVision FLEX reagents (Dako) with an autoimmunostainer (Dako) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The immunohistochemical staining results were scored independently by two pathologists. The p16 immunostain was considered aberrant (overexpression) if >75% tumor cells showed strong nuclear and cytoplasmic immunoreactivity. The p53 immunostain was considered aberrant if >75% tumor cells showed strong nuclear immunoreactivity (overexpression) or no staining was found in any of the tumor cells (null staining), and was considered wild-type if the tumor cells showed heterogeneous patchy positivity. Similarly, the estrogen receptor stain was considered positive if >5% of tumor cells were immunoreactive. The cytoplasmic mammaglobin staining was evaluated using scoring system from 0 to score 3, as previously described, and scores 2 or 3 were considered positive.28

Statistical Analysis

The difference of overall survival between the re-classified serous carcinoma group and the confirmed high-grade endometrioid carcinoma group was calculated by Fisher’s exact test.

Results

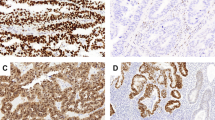

Based on recognition of ambiguous histomorphologic pattern of serous carcinoma, and aberrant staining for p53 and p16, 11 (34%) cases initially diagnosed as pure high-grade endometrioid carcinoma were re-classified as serous carcinoma (Table 1). Five of the 9 (56%) cases initially diagnosed as mixed high-grade endometrioid carcinoma/serous carcinoma were re-classified as pure serous carcinoma, based on aberrant staining for both p53 and p16, performed on representative slides containing both serous and endometrioid-like histologic appearance, while the remaining 4 (44%) cases with wild-type staining for p53 and patchy staining for p16 were considered as pure high-grade endometrioid carcinoma. Similarly, two other cases previously diagnosed as mixed high-grade endometrioid carcinoma/clear cell carcinoma were re-classified as pure serous carcinoma and pure high-grade endometrioid carcinoma, respectively, based on their immunoprofile. Histologically, all 17 cases re-classified as serous carcinoma showed predominantly glandular architecture but exhibited cytomorphologic characteristics of serous carcinoma, including ragged luminal borders, pleomorphic cuboidal cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, hobnail nuclei with loss of nuclear polarity, prominent nucleoli or macronucleoli, and increased mitoses with or without atypical forms (Figure 1). All 17 cases showed overexpression for p53 (Figure 2a) and p16 (Figure 2b), and were entirely negative for mammaglobin (Figure 2c). None of the cases showed null staining for p53. The estrogen receptor was positive in 6/11 cases (35%), while negative in 11/17 cases (65%) (Figure 2d; Table 2). The remaining 26 cases of confirmed high-grade endometrioid carcinoma showed wild-type staining for p53 in 25 (96%) and patchy staining for p16 in 20 (77%) of cases. The mammaglobin was positive in 8/26 (31%) and estrogen receptor was positive in 19/26 (73%) cases.

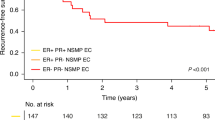

Six out of 17 (35%) patients with re-classified serous carcinoma presented at FIGO stage I, 2/17 (12%) at FIGO stage II, 8/17 (47%) at FIGO stage III, and 1/17 (6%) at FIGO stage IV disease (Table 3). The other 26 patients with confirmed diagnosis of high-grade endometrioid carcinoma presented at FIGO Stage I in 13 (50%) cases, FIGO stage II in 4 (15%), FIGO stage III in 7 (27%), and FIGO stage IV in 2 (8%). In retrospective analysis, the patients with re-classified serous carcinoma had a significantly poorer clinical outcome, with only 3/17 (18%) patients alive on clinical follow-up. In contrast, 15/26 (58%) patients with confirmed diagnoses of high-grade endometrioid carcinoma were disease free at the follow-up (Table 3).

Of note, although the stage of the disease was not correlated that well between the re-classified serous carcinoma and confirmed high-grade endometrioid carcinoma groups, the disease-free survival was, with significant difference in disease-free survival between those two groups (P<0.05 with Fisher's exact test; Table 3).

Discussion

In the current study, 40% (17/43) of cases of high-grade endometrial carcinomas initially diagnosed as high-grade endometrioid carcinoma on histology alone were retrospectively re-classified as serous carcinoma, when the ambiguous glandular histologic pattern of serous carcinoma has been recognized, and specific immunohistochemical panel was used. Similarly, a recent study also reported that up to 90% of endometrial carcinoma initially diagnosed as mixed or ambiguous carcinoma were re-classified as serous carcinoma after immunostaining for p53 and p16.29 Thus, our findings are in agreement with previously reported studies demonstrating difficulty and poor inter-observer diagnostic concordance in differentiating serous carcinoma from high-grade endometrioid carcinoma based on histomorphology only.16, 19, 20 Due to the aggressive behavior of serous carcinoma and more aggressive treatment, the possibility of potentially underdiagnosed serous carcinoma requires consideration of several important issues: subsets of serous carcinoma with a component of glandular histomorphology can be misdiagnosed as high-grade endometrioid carcinoma, which may result in sub-optimal surgical staging and treatment that might affect the disease-free and overall survival in these patients, as well as accurate selection of patients for prospective clinical trials.

The majority of patients (53%) with re-classified serous carcinoma in our study initially presented at FIGO stage III or IV disease, whereas only 35% of patients with confirmed high-grade endometrioid carcinoma presented at FIGO stage III or IV disease. Moreover, in retrospective analysis, patients with re-classified serous carcinoma had poor clinical outcomes in the study. Due to aggressive nature of serous carcinoma, it is crucial to recognize the existence of a subset of serous carcinoma with ambiguous histological features, including glandular histologic pattern along with cytomorphologic features characteristic of serous carcinoma. In addition, the background histological findings such as endometrial atrophy or serous intraepithelial carcinoma in the absence of squamous and/or mucinous metaplasia/differentiation would strongly argue in favor of serous carcinoma. The recognition of these histomorphologic features should be utilized in conjunction with sensitive and specific immunomarkers to identify this ambiguous subset of serous carcinoma.

While utilization of immunochemical panel has already been implemented as a standard work-up for difficult cases of high-grade endometrial carcinoma in distinguishing between high-grade endometrioid carcinoma and serous carcinoma, in our experience with consultation cases we still encounter underdiagnosed serous carcinoma that were rendered based on histomorphologic features alone. Based on our study as a single institution experience, we would like to raise awareness among the Pathology Community that, even as of now, many patients might still be sub-optimally staged and undertreated due to diagnostic error.

In the current study, we demonstrate that mammaglobin is a highly specific marker for diagnosing serous carcinoma when combined with sensitive immunohistochemical markers p53 and p16. Recent molecular studies have identified diverse genetic mutations in the development of endometrioid carcinoma and serous carcinoma. While endometrioid carcinomas are associated with microsatellite instability along with PTEN, KRAS, PIK3CA, ARID1A and CTNNB1 mutations, serous carcinomas are associated with TP53, PPP2R1A and PIK3CA mutations.1, 30, 31, 32 As a result, p53 has been developed as a sensitive marker for the diagnosis of serous carcinoma. However, a subset of serous carcinoma may harbor TP53 mutations resulting in the absence (null) p53 protein expression.33 Moreover, the p53 overexpression has been also reported in some cases of high-grade endometrioid carcinoma.2, 13, 23 Hence, the combination of p53 and p16 immunohistochemical markers along with mammaglobin is superior to p53 and/or p16 alone in identifying serous carcinoma with ambiguous morphology. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the expression of mammaglobin along with previously recognized sensitive immunomarkers, such as p53 and p16, in supporting the diagnosis of serous carcinoma. The expression of ret finger protein was once proposed to be helpful in differentiating serous carcinoma and endometrioid carcinomas, however, a more recent study revealed that ret finger protein expression is associated both with high-grade endometrioid carcinoma and with serous carcinoma.34 Previous studies have also shown that retention of PTEN is highly specific for the diagnosis of serous carcinoma when utilized with either p53 or p16.8, 17, 27, 35 However, the PTEN staining pattern and its interpretation can vary depending on the type of commercially utilized antibody to PTEN.1, 36 In contrast, mammaglobin cytoplasmic staining is easy to interpret with moderate to strong intensity observed both in benign and hyperplastic endometrium and endometrioid carcinoma.28 Hence, the presence of mammaglobin staining strongly suggests an endometrioid immunophenotype.

The immunostaining profile of mammaglobin in uterine high-grade endometrioid carcinoma and serous carcinoma was first studied by Onuma et al.28 who reported that only 1/8 (13%) of serous carcinoma cases were positive for mammaglobin expression, compared with 5/7 (71%) of high-grade endometrioid carcinoma cases showing positive staining. Another recent study showed that mammaglobin was positive in 7/31 (23%) of uterine serous carcinoma cases and 12/21 (57%) of endometrioid carcinoma (mostly low-grade) using a different cut-off.37 In our hands, mammaglobin demonstrated 100% specificity with absence of staining in all 17 re-classified serous carcinoma cases, which is more comparable with the Onuma et al study. It should be noted, however, that all three studies were performed on a limited number of cases. The fact that there was not a single case showing mammaglobin positivity in our study indicates that mammaglobin can possibly be a promising addition to the already available immunochemical panel in accurately diagnosing high-grade endometrial carcinoma. Therefore, larger studies might be necessary to determine the usefulness of mammaglobin in differentiating uterine serous carcinoma from high-grade endometrioid carcinoma. It would also be helpful to consider a parallel comparison of mammaglobin and PTEN staining, and to evaluate the utilization of both markers along with p53 and p16, in differentiating between these two types of high-grade endometrial carcinoma.

In conclusion, this study was performed to help delineate a useful panel of immunostains that can be implemented when differentiating within a diverse group of high-grade endometrial carcinomas that often present a diagnostic challenge. Utilizing the current immunochemical panel with addition of mammaglobin may aid in the accurate diagnosis of histomorphologically ambiguous serous carcinoma cases, and provide an appropriate surgical staging and therapeutic approach for the patients.

References

Soslow RA . High-grade endometrial carcinomas - strategies for typing. Histopathology 2013;62:89–110.

Alvarez T, Miller E, Duska L et al. Molecular profile of grade 3 endometrioid endometrial carcinoma: is it a type I or type II endometrial carcinoma? Am J Surg Pathol 2012;36:753–761.

Bokhman JV . Two pathogenetic types of endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 1983;15:10–17.

Setiawan VW, Yang HP, Pike MC et al. Type I and II endometrial cancers: have they different risk factors? J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2607–2618.

Moore KN, Fader AN . Uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2011;54:278–291.

Ueda SM, Kapp DS, Cheung MK et al. Trends in demographic and clinical characteristics in women diagnosed with corpus cancer and their potential impact on the increasing number of deaths. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;198:218 e1–e6.

Hamilton CA, Cheung MK, Osann K et al. Uterine papillary serous and clear cell carcinomas predict for poorer survival compared to grade 3 endometrioid corpus cancers. Br J Cancer 2006;94:642–646.

Alkushi A, Kobel M, Kalloger SE et al. High-grade endometrial carcinoma: serous and grade 3 endometrioid carcinomas have different immunophenotypes and outcomes. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2010;29:343–350.

Creasman WT, Kohler MF, Odicino F et al. Prognosis of papillary serous, clear cell, and grade 3 stage I carcinoma of the endometrium. Gynecol Oncol 2004;95:593–596.

Soslow RA, Bissonnette JP, Wilton A et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of 187 high-grade endometrial carcinomas of different histologic subtypes: similar outcomes belie distinctive biologic differences. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:979–987.

Boruta DM 2nd, Gehrig PA, Fader AN et al. Management of women with uterine papillary serous cancer: a Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) review. Gynecol Oncol 2009;115:142–153.

Wei JJ, Paintal A, Keh P . Histologic and immunohistochemical analyses of endometrial carcinomas: experiences from endometrial biopsies in 358 consultation cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2013;137:1574–1583.

Chiang S, Soslow RA . Updates in diagnostic immunohistochemistry in endometrial carcinoma. Semin Diagn Pathol 2014;31:205–215.

Malpica A . How to approach the many faces of endometrioid carcinoma. Mod Pathol 2016;29 (Suppl 1):S29–S44.

Gatius S, Matias-Guiu X . Practical issues in the diagnosis of serous carcinoma of the endometrium. Mod Pathol 2016;29 (Suppl 1):S45–S58.

Garg K, Leitao MM Jr., Wynveen CA et al. p53 overexpression in morphologically ambiguous endometrial carcinomas correlates with adverse clinical outcomes. Mod Pathol 2010;23:80–92.

Darvishian F, Hummer AJ, Thaler HT et al. Serous endometrial cancers that mimic endometrioid adenocarcinomas: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of a group of problematic cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:1568–1578.

Geels YP, van der Putten LJ, van Tilborg AA et al. Immunohistochemical and genetic profiles of endometrioid endometrial carcinoma arising from atrophic endometrium. Gynecol Oncol 2015;137:245–251.

Thomas S, Hussein Y, Bandyopadhyay S et al. Interobserver variability in the diagnosis of uterine high-grade endometrioid carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2016;140:836–843.

Gilks CB, Oliva E, Soslow RA . Poor interobserver reproducibility in the diagnosis of high-grade endometrial carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2013;37:874–881.

Hoang LN, Kinloch MA, Leo JM et al. Interobserver agreement in endometrial carcinoma histotype diagnosis varies depending on The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)-based molecular subgroup. Am J Surg Pathol 2017;41:245–252.

Chan JK, Loizzi V, Youssef M et al. Significance of comprehensive surgical staging in noninvasive papillary serous carcinoma of the endometrium. Gynecol Oncol 2003;90:181–185.

Soslow RA, Shen PU, Chung MH et al. Distinctive p53 and mdm2 immunohistochemical expression profiles suggest different pathogenetic pathways in poorly differentiated endometrial carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1998;17:129–134.

King SA, Adas AA, LiVolsi VA et al. Expression and mutation analysis of the p53 gene in uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Cancer 1995;75:2700–2705.

Tashiro H, Isacson C, Levine R et al. p53 gene mutations are common in uterine serous carcinoma and occur early in their pathogenesis. Am J Pathol 1997;150:177–185.

Yemelyanova A, Ji H, Shih IeM et al. Utility of p16 expression for distinction of uterine serous carcinomas from endometrial endometrioid and endocervical adenocarcinomas: immunohistochemical analysis of 201 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:1504–1514.

Chen W, Husain A, Nelson GS et al. Immunohistochemical profiling of endometrial serous carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2017;36:128–139.

Onuma K, Dabbs DJ, Bhargava R . Mammaglobin expression in the female genital tract: immunohistochemical analysis in benign and neoplastic endocervix and endometrium. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2008;27:418–425.

Espinosa I, D'Angelo E, Palacios J et al. Mixed and ambiguous endometrial carcinomas: a heterogenous group of tumors with different clinicopathologic and molecular genetic features. Am J Surg Pathol 2016;40:972–981.

Sherman ME . Theories of endometrial carcinogenesis: a multidisciplinary approach. Mod Pathol 2000;13:295–308.

McConechy MK, Ding J, Cheang MC et al. Use of mutation profiles to refine the classification of endometrial carcinomas. J Pathol 2012;228:20–30.

Rutgers JK . Update on pathology, staging and molecular pathology of endometrial (uterine corpus) adenocarcinoma. Future Oncol 2015;11:3207–3218.

Tashiro H, Lax SF, Gaudin PB et al. Microsatellite instability is uncommon in uterine serous carcinoma. Am J Pathol 1997;150:75–79.

Ussakli C, Usubutun A, Dincer N et al. Serous versus high-grade endometrioid endometrial carcinoma: immunohistochemistry of RFP is not useful for differentiation. Pol J Pathol 2016;67:221–227.

Risinger JI, Hayes K, Maxwell GL et al. PTEN mutation in endometrial cancers is associated with favorable clinical and pathologic characteristics. Clin Cancer Res 1998;4:3005–3010.

Pallares J, Bussaglia E, Martinez-Guitarte JL et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of PTEN in endometrial carcinoma: a tissue microarray study with a comparison of four commercial antibodies in correlation with molecular abnormalities. Mod Pathol 2005;18:719–727.

Hagemann IS, Pfeifer JD, Cao D . Mammaglobin expression in gynecologic adenocarcinomas. Hum Pathol 2013;44:628–635.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, S., Hinson, J., Matnani, R. et al. Are the uterine serous carcinomas underdiagnosed? Histomorphologic and immunohistochemical correlates and clinical follow up in high-grade endometrial carcinomas initially diagnosed as high-grade endometrioid carcinoma. Mod Pathol 31, 358–364 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2017.131

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2017.131

This article is cited by

-

A 4-gene signature predicts prognosis of uterine serous carcinoma

BMC Cancer (2021)

-

Impact of endometrial carcinoma histotype on the prognostic value of the TCGA molecular subgroups

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2020)

-

Impact of TP53 immunohistochemistry on the histological grading system for endometrial endometrioid carcinoma

Modern Pathology (2019)