Abstract

Standard molecular classification of endometrial cancers (EC) is now endorsed by the WHO and identifies p53-abnormal (p53abn) EC as the subgroup with the poorest prognosis and the most likely to benefit from adjuvant chemo(radio)therapy. P53abn EC are POLE wildtype, mismatch repair proficient and show abnormal immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for p53. Correct interpretation of routinely performed p53 IHC has therefore become of paramount importance. We aimed to comprehensively investigate abnormal p53 IHC patterns and their relation to clinicopathological and molecular features. Tumor material of 411 molecularly classified high-risk EC from consenting patients from the PORTEC-3 clinical trial were collected. p53 IHC was successful in 408 EC and was considered abnormal when the tumor showed a mutant expression pattern (including subclonal): overexpression, null or cytoplasmic. The presence of pathogenic mutations was determined by next generation sequencing (NGS). Abnormal p53 expression was observed in 131/408 (32%) tumors. The most common abnormal p53 IHC pattern was overexpression (n = 89, 68%), followed by null (n = 12, 9%) and cytoplasmic (n = 3, 2%). Subclonal abnormal p53 staining was observed in 27 cases (21%), which was frequently but not exclusively, associated with POLE mutations and/or MMRd (n = 22/27; p < 0.001). Agreement between p53 IHC and TP53 NGS was observed in 90.7%, resulting in a sensitivity and specificity of 83.6% and 94.3%, respectively. Excluding POLEmut and MMRd EC, as per the WHO-endorsed algorithm, increased the accuracy to 94.5% with sensitivity and specificity of 95.0% and 94.1%, respectively. Our data shows that awareness of the abnormal p53 IHC patterns are prerequisites for correct EC molecular classification. Subclonal abnormal p53 expression is a strong indicator for POLEmut and/or MMRd EC. No significant differences in clinical outcomes were observed among the abnormal p53 IHC patterns. Our data support use of the WHO-endorsed algorithm and combining the different abnormal p53 IHC patterns into one diagnostic entity (p53abn EC).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

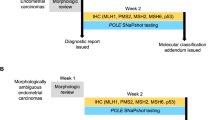

In 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) endorsed the molecular classification of endometrial carcinomas (EC) using surrogate markers and following a stepwise diagnostic algorithm1,2. This approach categorizes EC into four molecular classes with validated and reproducible prognostic significance3,4,5,6. Following this algorithm, all EC harboring a pathogenic mutation in the exonuclease domain of DNA polymerase epsilon (POLE) are classified as POLE-ultramutated (POLEmut) EC, regardless of mismatch repair (MMR) or p53 immunohistochemical (IHC) status. POLE wildtype (POLEwt) EC with loss of expression in one of the MMR proteins are classified as MMR-deficient (MMRd) EC, independent of p53 IHC status. The final step in the diagnostic algorithm uses p53 IHC to distinguish between EC without a specific molecular profile (NSMP) and p53-abnormal (p53abn) EC.

Most studies on the prognostic performance of this diagnostic algorithm have utilized p53 IHC to distinguish between p53abn and NSMP EC. The use of p53 IHC in the diagnostic algorithm is convenient, as it is widely available, inexpensive and interpretable by a (gyneco)pathologist. Some practices, however, use TP53 sequencing methods to molecularly classify EC as p53abn. Recent studies showed that abnormal p53 IHC reliably identifies cases with TP53 mutation in ovarian carcinoma (100% specificity and 96% sensitivity) and in EC biopsies (94% specificity and 91% sensitivity)7,8. This high conformity is reached when the three different abnormal p53 IHC patterns are recognized. The commonest of these is ‘mutant overexpression’ in which the majority (80–100%) of tumor cells show strong nuclear expression of p539. This mutant overexpression p53 IHC pattern is most often associated with missense mutations in the DNA binding domain of TP53. Other tumors show complete absence of p53 expression (‘null mutant’ pattern) and frequently have frameshift or nonsense mutations encoding truncated p53 protein. More recently, a third abnormal p53 IHC pattern has been recognized: overexpression of p53 in the cytoplasm of the tumor cells caused by mutations in the tetramerization or C-terminal domain of TP537. Given the reported high concordance between p53 IHC and sequencing results, it is hypothesized that replacing p53 IHC with next generation sequencing (NGS) with a panel that covers the complete TP53 gene would give comparable results, and that these two techniques (IHC or NGS) may be used interchangeably.

Recent reports have indicated that abnormal p53 expression can also occur confined to a distinct geographic area of the tumor, a pattern that has been termed ‘subclonal’ abnormal p53 expression8,10. In these cases, most typically, a well-defined area within a tumor shows an abnormal p53 IHC pattern, whilst the remaining tumor shows wildtype p53 expression. Depending on the area of the tumor from which DNA is extracted, it is conceivable that in tumors with subclonal abnormal p53 expression, a TP53 mutation is not always identified by sequencing methods. Moreover, subclonal abnormal p53 expression in EC is still relatively understudied and its definition is poorly described. Some have suggested the use of a threshold of at least 10% abnormal p53 expression to define subclonality4. However, in our practice and clinical trials we have also observed unequivocal mutant overexpression of p53 in tiny foci (<10%) within an otherwise p53 wildtype tumor.

The correct interpretation of p53 IHC is essential for the molecular EC classification diagnostic algorithm, because it significantly impacts a patient’s individual risk assessment and subsequent treatment11. Most studies validating the molecular EC classification have reported considerable differences in clinical outcomes between patients with NSMP and p53abn EC, with the latter group persistently showing poor clinical outcomes3,4,5,6. Furthermore, recent data suggest that patients with p53abn high-risk EC benefit from the addition of chemotherapy to adjuvant external beam radiotherapy in the adjuvant treatment setting4. This observation has led to the recommendation of combined adjuvant radiotherapy with chemotherapy for patients with stage I (with myometrial invasion)-IVA p53abn EC in the recently updated ESGO-ESTRO-ESP EC guideline11. Furthermore, therapeutic agents such as poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors in homologous deficient (HRD) EC and anti-HER2 therapies in HER2-positive EC are currently being explored12,13,14. Both HRD and HER2-positivity are highly, and in some studies exclusively, associated with p53abn EC, supporting p53abn subgroup-specific testing for HRD and HER2 status15,16.

In the current study, we aimed to comprehensively describe the clinicopathological and molecular features of p53abn EC, and to evaluate the concordance between p53 IHC and TP53 sequencing, in a large series of hysterectomy-derived EC samples from patients who participated in the PORTEC-3 clinical trial.

Methods

Patient and tissue selection

The study population comprised 424 consenting patients included in the international PORTEC-3 clinical trial and tumor material collected by the TransPORTEC research consortium. The design and results of the trial have been published previously4,17. In brief, 660 eligible patients with high-risk EC were randomly assigned 1:1 to postoperative chemoradiotherapy (CTRT) versus radiotherapy (RT) alone. Pathological inclusion criteria for the PORTEC-3 trial were: International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) 2009 stage IA grade 3 endometrioid EC (EEC) with LVSI; stage IB grade 3 EEC; stage II-IIIC EEC of any grade; or non-endometrioid EC with stages IA (with invasion), IB-IIIC. Patients with uterine (carcino)sarcomas were excluded from participation in the trial. Eligibility was confirmed by upfront central pathology review by reference gynaecopathologists. The study was approved by the ethics committees at all participating centers.

Molecular subgroup assignment (POLEmut, MMRd, NSMP or p53abn) according to the WHO 2020 guidelines was successful in 411 EC for whom tumor blocks were available. In our previous study4, a threshold of more than 10% for subclonal abnormal p53 expression was used to assign a MMR proficient and POLE wildtype tumor to the p53abn subgroup. Patient, tumor and treatment characteristics did not differ significantly between PORTEC-3 trial patients included and excluded from the molecular analyses, as reported previously4.

Immunohistochemistry

For each case, one representative formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor block had been previously selected by a pathologist during central pathology review of the PORTEC-3 trial. These blocks were stored for translational research at the department of pathology of the Leiden University Medical. Immunohistochemical staining of p53 (DO-7, 1:200; Agilent DAKO) was retrospectively performed on 4 μm whole slides in batches of 50–100 slides as described previously4. All p53 IHC slides had been initially scored by two pathologists for the purpose of the molecular classification4. This previous scoring did not differentiate any of the known p53 mutational patterns, nor was the percentage of mutant-type staining noted. Therefore, for the purpose of the current study we re-evaluated the p53-stained slides blinded to previous scores and any of the molecular data using a more detailed scoring system. Re-evaluation of all p53 IHC slides was done by one of the two original pathologists (ALC) and discordant scores were discussed at a consensus meeting with both pathologists (ALC and TB). The interval between the first and second evaluation of p53 IHC was 1.5 years. For this re-evaluation, abnormal p53 expression was categorized as follows; strong positive p53 expression in >80% of the tumor nuclei (mutant overexpression), complete absence of p53 expression with a positive internal control (null mutant) or significant cytoplasmic p53 expression (cytoplasmic) in >80% of the tumor8. Subclonal abnormal p53 expression was defined as any abrupt and regional abnormal p53 expression in less than 80% of the tumor volume. The percentage of subclonality was noted. Representative examples of all abnormal p53 IHC patterns are shown in Fig. 1. Wildtype p53 expression was defined as nuclear staining of variable intensity in 1–80% of the tumor8. P53 IHC was considered failed when there was complete absence of p53 expression without an internal positive control, defined as scattered positive staining of p53 with variable intensity in fibroblasts, endothelial cells or lymphocytes9. In addition, for the purpose of this study, “ambiguous” p53 expression was not considered a category, so that all cases got assigned one of the five p53 IHC patterns. This resulted in re-assignment of nine cases originally scored as ambiguous into p53 wildtype or p53-abnormal. Twelve cases, originally scored as p53 wildtype, upon re-evaluation were scored “any subclonal abnormal p53” resulting in a re-assignment to p53-abnormal molecular class. In addition, two cases originally scored as wildtype were re-assigned as p53-abnormal. The p53 IHC scores obtained after re-examination of the p53 IHC slides were used to evaluate the agreement with TP53 mutation status.

Next-generation sequencing

Targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) had previously been performed on PORTEC-3 tumor samples. A detailed description of DNA isolation and sequencing was described previously4. In brief, tumor DNA was collected by taking three random 0.8 mm tumoral tissue cores. For samples with low tumor volume, DNA was enriched by microdissection of selected tumoral areas using 5–10 tissue slides. Although DNA was isolated from the same tumor block, the p53 IHC slide was not used to direct the area of microdissection. Samples were sequenced in batches of 48 samples using the AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot Panel version 5, which included frequently mutated genes in EC and covered the TP53 gene in its entirety. The presence of pathogenic mutations was assessed blinded from the p53 IHC scores. Only variants with a predefined minimum coverage of 100 reads and variant allele frequency (VAF) of 10% were considered. Pathogenicity of non-synonymous mutations was assessed using the public International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) TP53 database18 and ClinVar database19. Only mutations classified as (likely) pathogenic were included in the analyses.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (Statistical Package of Social Science) version 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Five-year recurrence-free survival (RFS) was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier’s methodology and compared between groups using the log-rank test. The diagnostic performance of p53 IHC was determined by calculating the accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of p53 IHC compared to TP53 NGS analysis. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinicopathological characteristics

p53 IHC was successful in 408 molecularly classified high-risk EC (Fig. 2). Of these, 344 (84.3%) cases also had successful TP53 NGS analysis. Clinicopathological characteristics of the 408 cases included in this study are provided in Table 1. Most had endometrioid histology (n = 272, 66.7%) and FIGO stage II (n = 105, 25.7%) or stage III (n = 176, 43.1%) disease. We used hysterectomy samples in 96.6% (n = 394) of the cases.

Evaluation of p53 IHC

Overall p53 IHC staining quality was of sufficient standard to allow interpretation as wild-type or abnormal; although the blocks were from many different hospitals across the world, the variability in fixation did not hamper assessment in the majority of cases. Wildtype p53 expression was observed in 277/408 (77.9%) cases. Abnormal p53 expression was observed in 131/408 (32.1%) of the cases. The most common abnormal p53 IHC pattern was mutant overexpression (n = 89/131, 67.9%). Complete absence of p53 expression (null mutant pattern) was observed in twelve (9.2%) cases and significant cytoplasmic staining in three (2.3%) cases. Subclonal abnormal p53 expression was observed in 27 cases (20.6%), at levels ranging from <10 to 75%. In all cases the subclonal p53 staining presented as mutant overexpression. A detailed description of all cases with subclonal abnormal p53 expression is provided in Table 2. Interestingly, seventeen cases showed the presence of (multifocal) subclonal foci with nuclear overexpression of p53, comprising far less than 10% of the tumor (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Agreement of p53 IHC with TP53 mutation status

Conformity between p53 IHC and TP53 NGS analysis was observed in 312 of 344 cases using a binary classification (Table 3). The accuracy of the concordance between p53 IHC and TP53 NGS analysis was 90.7% (95% CI 87.6–93.8%), with a sensitivity of 83.6% (95% CI 79.7–87.5%) and a specificity of 94.3% (95% CI 91.8–96.7%). Of the 32 cases with discordances between p53 IHC and TP53 NGS analysis, 22 cases were either POLEmut or MMRd EC. Confining the analysis to POLEwt and MMRp EC, as per the WHO-endorsed algorithm, increased the accuracy to 94.5% (95% CI 89.4–99.6%) with a sensitivity of 95.0% (95% CI 90.2–99.8%) and a specificity of 94.1% (95% CI 88.9–99.3%) (Table 3).

Discordant cases

In total, 32 cases (9.3%) had discordant results between p53 IHC and TP53 NGS analysis (Supplementary Table S1). Firstly, there were 22 cases that were either POLEmut or MMRd EC. This included 5 POLEmut and 10 MMRd EC with a TP53 mutation that did not result in abnormal p53 expression, and 3 POLEmut and 4 MMRd EC which showed subclonal abnormal p53 IHC with no detectable TP53 mutation. In 4 cases the p53 immunostaining was likely erroneously interpreted. Two cases had missed null mutant patterns (Fig. 3A, B). In both cases a nonspecific nuclear blush was mistaken for wildtype p53 expression, which has been previously described as an artifact in true null mutant cases that can be encountered with more sensitive p53 IHC methods9. In addition, there was 1 case with a missed cytoplasmic p53 IHC pattern (Fig. 3C). In the fourth case the p53 IHC slide was overstained with nuclear positivity of the stroma and was therefore not reliably interpretable (Fig. 3D). Restaining p53 IHC in the latter case confirmed unequivocal wildtype p53 expression. The p53 IHC assignment of these 4 misinterpreted cases was corrected in the database for further analyses in this study (including the molecular landscape and survival analyses). The remaining 6 POLEwt and MMRp EC showed true discrepancies between IHC and NGS results: one case assigned as NSMP EC, based on wildtype p53 IHC, had a missense TP53 mutation. Re-examination of the p53 IHC revealed unequivocal wildtype p53 staining. Four cases had the mutant overexpression p53 IHC pattern without a detected TP53 mutation (Supplementary Fig. S2). All of these cases showed unambiguous mutant-type overexpression with optimal staining. Finally, 1 case with subclonal p53 IHC expression did not show a TP53 mutation.

Cases shown in (A–C) were scored p53 wildtype but did have a frameshift TP53 mutation (A, B) and nonsense TP53 mutation (C). In retrospect, p53 IHC should have been scored as null (A, B) and cytoplasmic (C). The case shown in (D) was assigned ‘p53 mutant overexpression’, however did not have a TP53 mutation. Given the high expression in the stromal cells, this case was probably overstained.

Molecular landscape of p53-abnormal and/or TP53-mutated HREC

Of the 344 cases with successful p53 IHC and TP53 NGS analysis, 128 cases had abnormal p53 IHC expression and/or a pathogenic TP53 mutation. The molecular landscape of these 128 cases is presented in Fig. 4. Within EC molecularly classified as p53abn, the most frequently observed genetic alterations were pathogenic mutations in TP53 (n = 78/82, 95.1%), PIK3CA (n = 25/82, 30.5%), PPP2R1A (n = 14/82, 17.1%), PTEN (n = 10/82, 12.2%), and FBXW7 (n = 8/82, 9.8%) and HER2 amplification (n = 20/82, 24.4%). Within the p53abn EC in our cohort, PPP2R1A mutations did not co-occur with PTEN and KRAS mutations, and rarely co-occurred with FBXW7 mutations (n = 1/78). Half of the p53abn EC were of serous histologic subtype (n = 41, 50.0%), followed by endometrioid (n = 21, 25.6%) and clear cell (n = 10, 12.2%) histologic subtypes.

Mutant overexpression of p53 was the most prevalent abnormal p53 IHC pattern and was found in EC with missense TP53 mutations (n = 63/73, 86.3%), nonsense mutations (n = 2/73, 2.7%), in-frame deletions (n = 2/73, 2.7%) and in one case (1.7%) with a splice-site mutation. Mutant overexpression of p53 was observed in five POLEmut and three MMRd EC. One of the POLEmut EC had two pathogenic TP53 mutations (missense and nonsense). Eighteen cases with mutant overexpression of p53 were HER2-positive (n = 18/73, 24.7%), compared to two cases within the null mutant group (n = 2/13, 15.4%).

The null mutant p53 IHC pattern was associated with frameshift (n = 8/13, 61.5%) and nonsense (n = 5/13, 38.5%) TP53 mutations. Two cases with cytoplasmic p53 expression showed a nonsense mutation in the tetramerization domain of p53. Neither null- or cytoplasmic p53 IHC patterns were encountered in the context of MMRd and POLEmut EC. Interestingly, none of the ECs with a null mutant or cytoplasmic p53 IHC pattern harbored PTEN mutations. In comparison, PTEN mutations were found in 13/74 (17.6%) EC with mutant overexpression of p53.

Cases with subclonal abnormal p53 expression showed a substantially different molecular profile, consistent with their molecular subgroup assignment as either MMRd or POLEmut EC. These cases had frequent mutations in PTEN (n = 18/24, 75.0%) and PIK3CA (n = 11/24, 45.8%) and were predominantly endometrioid EC (n = 19/24, 79.2%). In two thirds of the cases with a subclonal abnormal p53 IHC pattern (n = 16/24, 66.7%) a TP53 mutation was identified, even in 8 out of 15 cases with abnormal p53 expression in <10% of the tumor. Of interest, subclonal abnormal p53 expression was observed in two cases with non-endometrioid histology that were POLEwt and MMRp. In both cases subclonal abnormal p53 expression was observed in >50% of the tumor and a TP53 mutation was confirmed.

Like cases with a subclonal abnormal p53 IHC pattern, the majority of TP53 mutant EC with wildtype p53 IHC were molecularly classified as POLEmut or MMRd (n = 15/16, 93.8%) and harbored frequent mutations in PTEN (n = 8/16, 50.0%) and PIK3CA (n = 7/16, 43.8%). There was one POLEwt and MMRp serous EC that showed wildtype p53 expression that did have a missense TP53 mutation.

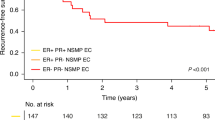

Prognostic relevance of abnormal p53 IHC patterns

Finally, we investigated the prognostic relevance of the different abnormal p53 IHC patterns within the group of patients with EC assigned as p53abn. There were no significant differences in 5-year recurrence rates between the mutant overexpression and null mutant p53 IHC patterns (49.1% [95% CI 37.6–60.6%] versus 57.1% [95% CI 31.2–83.0%] respectively, p = 0.57; Fig. 5). Of the three patients with cytoplasmic and two patients with subclonal abnormal p53 expression (in 60% and 75% of the tumor), the tumor recurred in one patient in both groups, resulting in overlapping survival curves (Supplementary Fig. S3A). Likewise, no significant differences in 5-year recurrence rate were observed among the different types of TP53 mutation in patients with p53abn EC (Supplementary Fig. S3B).

Discussion

In this large study of high-risk EC samples from hysterectomy specimens of patients included in the PORTEC-3 trial, we corroborate the abnormal p53 IHC patterns previously described in ovarian cancer and endometrial cancer biopsy samples7,8. We describe a novel finding that subclonal abnormal p53 expression can be observed in small multifocal areas comprising less than 10% of the tumor volume. We show that concordance between p53 IHC and TP53 mutational analysis using NGS in EC hysterectomy samples is good with an estimated accuracy of 90.7%. Furthermore, we find no significant differences among the abnormal p53 IHC patterns with regard to clinicopathological and molecular characteristics, nor in clinical outcomes, which supports combining the different abnormal p53 IHC patterns into one diagnostic entity (p53abn EC).

Few studies have reported on subclonal abnormal p53 IHC patterns. We observed subclonal abnormal p53 expression in up to 7% of cases, comparable to the prevalence of 5% in EC biopsies enriched for p53 mutant cases reported by Singh et al.8. In this study, we discovered that subclonality can also present as small multifocal areas in less than 10% of the tumor volume. In eight of fifteen cases with <10% subclonal abnormal p53 expression, a TP53 mutation was identified, supporting the hypothesis that this pattern represents true mutant subclones. In agreement with previous studies, we observed a strong association between subclonal abnormal p53 expression and POLE mutations and MMRd. Here, the TP53 mutation is likely acquired at a later stage of tumor progression and previous work suggest this does not influence clinical behavior20. It has been argued that subclonal abnormal p53 expression can be a selection criterion for POLE testing in EC with normal MMR IHC expression. Although there may be some enrichment for POLEmut EC using this approach, a large number of POLEmut EC would not be identified20. Despite the strong association between subclonal abnormal p53 expression and POLEmut and MMRd EC, we observed five cases with subclonal abnormal p53 expression in POLEwt and MMRp EC. This suggests that EC can also acquire TP53 mutations during tumor progression outside the context of POLEmut and MMRd EC. It is currently unclear whether these subclones become more dominant during tumor progression and subsequently increase the patients’ risk for metastases or recurrence. As a result, there is no consensus definition for subclonal abnormal p53 expression in this specific context. Previous studies have used a lower-limit cut-off of more than 10% for molecular subgroup assignment of these rare cases4,21,22. Given the lack of robust clinical data to suggest otherwise, we endorse the continued use of this threshold for uniformity.

We report a high agreement between p53 IHC and TP53 NGS analysis of 90.7% overall and 94.5% when used as part of the recommended algorithm, comparable to the agreement reported in ovarian cancer and EC biopsies7,8. Most discordances between p53 IHC and TP53 NGS analysis occurred in POLEmut and MMRd EC. These discordances might be explained by TP53 mutations that occur at a later stage of tumor progression, resulting in subclonal abnormal p53 expression. Here, TP53 mutations can be missed when DNA is not isolated from the area of the tumor showing abnormal p53 expression. In contrast, by coring FFPE tumor blocks it is possible that TP53 mutations in p53 mutant subclones, that lie deeper than the whole slide p53 IHC, are being detected. In addition to the discordances in POLEmut and MMRd EC, we observed ten discordant cases which were eventually classified as NSMP or p53abn EC, all of which are discussed in more detail in the results. One case with subclonal p53 expression in less than 10% of the tumor did not have a TP53 mutation. Five cases with unequivocal wildtype or mutant overexpression p53 IHC pattern that did not correspond with TP53 NGS analysis. Four other discordances could be explained by erroneously interpreted p53 IHC. Three cases were called p53 wildtype by IHC but did have a TP53 mutation. On review, these cases represented null mutant and cytoplasmic p53 expression, well-known pitfalls in p53 IHC interpretation. One other discordant case was called p53 abnormal by IHC without a TP53 mutation found by NGS. Here, the p53 IHC slide was overstained with nuclear positivity of the stroma and was therefore not reliably interpretable. These discordant cases illustrate the importance of a quality-assured p53 immunostaining procedure, good internal controls, optimal pre-processing of tumor tissue and awareness of all the different abnormal p53 IHC patterns when molecularly classifying EC. We did not add external positive controls to our slides as, in this research-setting, we had a sufficient number of p53 mutant cases in each IHC run. However, in a clinical setting a good external on-slide positive control (e.g. a low-expressor, like tonsil) is common practice and highly recommended to support correct interpretation of cases that fall into the zone of potential misclassification.

Currently, it is unknown which method of p53 testing should be preferred when it comes to identifying p53abn EC. In previous studies, p53 IHC was most often used and has therefore proven prognostic value3,4,5,6. Given the high concordance between p53 IHC and TP53 sequencing methods, it is likely that identical results can be obtained using TP53 NGS analysis. However, in many practices NGS is not (yet) incorporated in routine clinical practice, as it is costly and requires the expertise of molecular biologists and bioinformaticians to analyze the results. Conversely, p53 IHC is widely available, relatively easy to interpret, allows for quick turn-around and is currently considerably cheaper than TP53 sequencing. Taken together, although p53 IHC and NGS can probably be used interchangeably, there are sufficient arguments to favor p53 IHC to assign p53abn EC.

In agreement with existing literature, we have shown that mutant overexpression of p53 in EC is predominantly associated with missense TP53 mutations. In addition, the null mutant pattern is associated with frameshift and nonsense TP53 mutations, and the cytoplasmic IHC pattern with nonsense mutations in the tetramerization domain of TP53. In our study, the null mutant and cytoplasmic p53 IHC patterns were not identified within POLEmut and MMRd EC and in this group we did not see pathogenic PTEN mutations. These findings are interesting and may point towards a different underlying biology but should still be interpreted with caution as the total number of cases is limited.

To date, no studies have investigated the prognostic relevance of the different abnormal p53 IHC patterns and/or types of TP53 mutation within EC. A study investigating 141 head and neck squamous cell carcinomas reported worse clinical outcomes for patients with truncating TP53 mutations compared to patients with wildtype TP53, whilst missense TP53 mutations did not influence prognosis23. In breast cancer literature inconsistent results have been reported regarding the impact of TP53 mutation types on clinical outcome24,25,26,27. In our study, we did not observe a significant difference in recurrence rate between the different abnormal p53 IHC patterns observed in EC, nor between TP53 mutation types, within p53abn EC. This finding supports the practice of combining all abnormal p53 IHC patterns into one diagnostic entity (p53abn EC).

Although our data supports the use of p53 IHC to assign p53abn subtype in practice, we acknowledge that our results are obtained in a research setting potentially impacting generalizability. First, we performed p53 IHC and TP53 NGS runs in batches and all in a single laboratory, not reflecting the real-world. We know that in practice interlaboratory differences in p53 IHC protocols exist which may impact accuracy, as also highlighted by the work of Köbel et al. in EC and OC7. We therefore used the recommended DAKO D07 antibody, which showed the best performance and a high interobserver agreement in previous work7. Second, experts with experience in p53 IHC scoring in EC were used as reference in our study. It has been established by Singh et al. that experts have a high agreement of p53 IHC in EC biopsy samples8. However, it will be important for less experienced pathologists to get acquainted with the abnormal p53 IHC patterns in EC that are highlighted in this manuscript. To support training, we encourage the use of the previous published tutorial on this topic (http://www.gpec.ubc.ca/p53). Finally, improper preprocessing of tumor tissue may negatively impact the immunohistochemical staining of p53 and subsequently cause difficulties in interpretation. It was reassuring that we did not encounter any major difficulties, despite the use of blocks with variable fixation collected from many different hospitals. The agreement between p53 IHC and TP53 NGS in our cohort of EC hysterectomy samples was comparable to the agreement reported in EC biopsy samples, which are generally better fixed8. In practice, a pre-operative EC (biopsy) sample is often available and could be utilized for confirmatory p53 IHC staining in cases with poor fixation of the hysterectomy specimen.

This is, to our knowledge, the first study investigating abnormal p53 IHC patterns and their association with clinicopathological and molecular features in EC hysterectomy samples. In addition to the previously reported four abnormal p53 IHC patterns in EC, we discovered that subclonal abnormal p53 expression can also present as small multifocal foci in <10% of the tumor. Furthermore, we have shown that subclonal abnormal p53 expression frequently occurs in the context of POLEmut and MMRd EC. We conclude that p53 IHC and TP53 NGS analysis have high concordance, with a diagnostic accuracy comparable to EC biopsy samples and ovarian cancer. Proper technical performance of p53 IHC and acquaintance by the pathologist with the different abnormal p53 IHC patterns are prerequisites for correct molecular subgroup assignment. We recommend, at least, the use of TP53 NGS analysis in EC with ambiguous p53 expression, in MMR proficient and POLE wildtype EC. Our findings continue to support the use of p53 IHC as part of the diagnostic algorithm for the molecular classification of EC.

Data availability

The PORTEC-3 dataset analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Vermij, L., Smit, V., Nout, R. & Bosse, T. Incorporation of molecular characteristics into endometrial cancer management. Histopathology 76, 52-63 (2020).

WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. WHO Classification of Female Genital Tumours. 5th edn, (International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, 2020).

Stelloo, E., Nout, R. A., Osse, E. M., Jurgenliemk-Schulz, I. J., Jobsen, J. J., Lutgens, L. C. et al. Improved Risk Assessment by Integrating Molecular and Clinicopathological Factors in Early-stage Endometrial Cancer-Combined Analysis of the PORTEC Cohorts. Clin. Cancer Res. 22, 4215-4224 (2016).

Leon-Castillo, A., de Boer, S. M., Powell, M. E., Mileshkin, L. R., Mackay, H. J., Leary, A. et al. Molecular Classification of the PORTEC-3 Trial for High-Risk Endometrial Cancer: Impact on Prognosis and Benefit From Adjuvant Therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 3388-3397 (2020).

Talhouk, A., McConechy, M. K., Leung, S., Li-Chang, H. H., Kwon, J. S., Melnyk, N. et al. A clinically applicable molecular-based classification for endometrial cancers. Br. J. Cancer 113, 299-310 (2015).

Kommoss, S., McConechy, M. K., Kommoss, F., Leung, S., Bunz, A., Magrill, J. et al. Final validation of the ProMisE molecular classifier for endometrial carcinoma in a large population-based case series. Ann. Oncol. 29, 1180-1188 (2018).

Kobel, M., Piskorz, A. M., Lee, S., Lui, S., LePage, C., Marass, F. et al. Optimized p53 immunohistochemistry is an accurate predictor of TP53 mutation in ovarian carcinoma. J. Pathol. Clin. Res. 2, 247-258 (2016).

Singh, N., Piskorz, A. M., Bosse, T., Jimenez-Linan, M., Rous, B., Brenton, J. D. et al. p53 immunohistochemistry is an accurate surrogate for TP53 mutational analysis in endometrial carcinoma biopsies. J. Pathol. 250, 336-345 (2020).

Kobel, M., Ronnett, B. M., Singh, N., Soslow, R. A., Gilks, C. B. & McCluggage, W. G. Interpretation of P53 Immunohistochemistry in Endometrial Carcinomas: Toward Increased Reproducibility. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 38 Suppl 1, S123-S131 (2019).

Kobel, M. & Kang, E. Y. The Many Uses of p53 Immunohistochemistry in Gynecological Pathology: Proceedings of the ISGyP Companion Society Session at the 2020 USCAP Annual9 Meeting. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 40, 32-40 (2021).

Concin, N., Matias-Guiu, X., Vergote, I., Cibula, D., Mirza, M. R., Marnitz, S. et al. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 31, 12-39 (2021).

Fader, A. N., Roque, D. M., Siegel, E., Buza, N., Hui, P., Abdelghany, O. et al. Randomized Phase II Trial of Carboplatin-Paclitaxel Compared with Carboplatin-Paclitaxel-Trastuzumab in Advanced (Stage III-IV) or Recurrent Uterine Serous Carcinomas that Overexpress Her2/Neu (NCT01367002): Updated Overall Survival Analysis. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 3928-3935 (2020).

Fader, A. N., Roque, D. M., Siegel, E., Buza, N., Hui, P., Abdelghany, O. et al. Randomized Phase II Trial of Carboplatin-Paclitaxel Versus Carboplatin-Paclitaxel-Trastuzumab in Uterine Serous Carcinomas That Overexpress Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2/neu. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, 2044-2051 (2018).

Post, C. C. B., Westermann, A. M., Bosse, T., Creutzberg, C. L. & Kroep, J. R. PARP and PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibition in recurrent or metastatic endometrial cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 152, 102973 (2020).

Vermij, L., Horeweg, N., Leon-Castillo, A., Rutten, T. A., Mileshkin, L. R., Mackay, H. J. et al. HER2 Status in High-Risk Endometrial Cancers (PORTEC-3): Relationship with Histotype, Molecular Classification, and Clinical Outcomes. Cancers (Basel) 13 (2020).

de Jonge, M. M., Ritterhouse, L. L., de Kroon, C. D., Vreeswijk, M. P. G., Segal, J. P., Puranik, R. et al. Germline BRCA-Associated Endometrial Carcinoma Is a Distinct Clinicopathologic Entity. Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 7517-7526 (2019).

de Boer, S. M., Powell, M. E., Mileshkin, L., Katsaros, D., Bessette, P., Haie-Meder, C. et al. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone in women with high-risk endometrial cancer (PORTEC-3): patterns of recurrence and post-hoc survival analysis of a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 20, 1273-1285 (2019).

Bouaoun, L., Sonkin, D., Ardin, M., Hollstein, M., Byrnes, G., Zavadil, J. et al. TP53 Variations in Human Cancers: New Lessons from the IARC TP53 Database and Genomics Data. Hum Mutat. 37, 865-876 (2016).

Landrum, M. J., Lee, J. M., Riley, G. R., Jang, W., Rubinstein, W. S., Church, D. M. et al. ClinVar: public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D980-985 (2014).

Leon-Castillo, A., Gilvazquez, E., Nout, R., Smit, V. T., McAlpine, J. N., McConechy, M. et al. Clinicopathological and molecular characterisation of ‘multiple-classifier’ endometrial carcinomas. J. Pathol. 250, 312-322 (2020).

Liu, J., Li, W., Deng, M., Liu, D., Ma, Q. & Feng, X. Immunohistochemical Determination of p53 Protein Overexpression for Predicting p53 Gene Mutations in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 11, e0159636 (2016).

Guedes, L. B., Almutairi, F., Haffner, M. C., Rajoria, G., Liu, Z., Klimek, S. et al. Analytic, Preanalytic, and Clinical Validation of p53 IHC for Detection of TP53 Missense Mutation in Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 4693-4703 (2017).

Lindenbergh-van der Plas, M., Brakenhoff, R. H., Kuik, D. J., Buijze, M., Bloemena, E., Snijders, P. J. et al. Prognostic significance of truncating TP53 mutations in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 3733-3741 (2011).

Silwal-Pandit, L., Vollan, H. K., Chin, S. F., Rueda, O. M., McKinney, S., Osako, T. et al. TP53 mutation spectrum in breast cancer is subtype specific and has distinct prognostic relevance. Clin. Cancer Res. 20, 3569-3580 (2014).

Fernandez-Cuesta, L., Oakman, C., Falagan-Lotsch, P., Smoth, K. S., Quinaux, E., Buyse, M. et al. Prognostic and predictive value of TP53 mutations in node-positive breast cancer patients treated with anthracycline- or anthracycline/taxane-based adjuvant therapy: results from the BIG 02-98 phase III trial. Breast Cancer Res. 14, R70 (2012).

Powell, B., Soong, R., Iacopetta, B., Seshadri, R. & Smith, D. R. Prognostic significance of mutations to different structural and functional regions of the p53 gene in breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 6, 443-451 (2000).

Vegran, F., Rebucci, M., Chevrier, S., Cadouot, M., Boidot, R. & Lizard-Nacol, S. Only missense mutations affecting the DNA binding domain of p53 influence outcomes in patients with breast carcinoma. PLoS One 8, e55103 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Tessa Rutten, Natalja ter Haar and Enno Dreef (Department of Pathology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands) for their technical support. We thank Maurice de Haan for his assistance in the NGS analysis. We thank Tom van Wezel (Department of Pathology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands) for his help with the TP53 mutational analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society Research Project Grants (TB, 31843). EJC is supported by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Advanced Fellowship (NIHR300650) and the NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Center (IS-BRC-1215–20007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

L.V., A.L.C. and T.B. carried out experiments and analyzed data, N.H. analyzed data. All authors were involved in writing the paper and had final approval of the submitted and published version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Dutch Cancer Society (ethic code: CKTO 2006–4) and medical ethics committees at participating centers in 2006 (ethic codes: P06.031 (CME LUMC), C7925/A8659 CCTAAC, UK), (NCIC CTG EN 7 CNCIC CTG) and FEDEQYN 01/0904 (UNICANCER).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vermij, L., Léon-Castillo, A., Singh, N. et al. p53 immunohistochemistry in endometrial cancer: clinical and molecular correlates in the PORTEC-3 trial. Mod Pathol 35, 1475–1483 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-022-01102-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-022-01102-x

This article is cited by

-

Molekulare Klassifikation des Endometriumkarzinoms – ein kurzer Überblick

Die Onkologie (2023)

-

Gynäkologische Krebserkrankungen und Fertilität

Forum (2023)

-

Molekulare Klassifikation des Endometriumkarzinoms – ein kurzer Überblick

Die Pathologie (2023)

-

Real-world routine diagnostic molecular analysis for TP53 mutational status is recommended over p53 immunohistochemistry in B-cell lymphomas

Virchows Archiv (2023)