Abstract

Smooth muscle tumors are here considered an essentially dichotomous group composed of benign leiomyomas and malignant leiomyosarcomas. Soft tissue smooth muscle tumors with both atypia and mitotic activity are generally diagnosed leiomyosarcomas acknowledging potential for metastasis. However, lesions exist that cannot be comfortably placed in either category, and in such cases the designation ‘smooth muscle tumor of uncertain biologic potential’ is appropriate. The use of this category is often necessary with limited sampling, such as needle core biopsies. Benign smooth muscle tumors include smooth muscle hamartoma and angioleiomyoma. A specific category of leiomyomas are estrogen-receptor positive ones in women. These are similar to uterine leiomyomas and can occur anywhere in the abdomen and abdominal wall. Leiomyosarcomas can occur at any site, although are more frequent in the retroperitoneum and proximal extremities. They are recognized by likeness to smooth muscle cells but can undergo pleomorphic evolution (‘dedifferentiation’). Presence of smooth muscle actin is nearly uniform and desmin-positivity usual. This and the lack of KIT expression separate leiomyosarcoma from GIST, an important problem in abdominal soft tissues. EBV-associated smooth muscle tumors are a specific subcategory occurring in AIDS or post-transplant patients. These tumors can have incomplete smooth muscle differentiation but show nuclear EBER as a diagnostic feature. In contrast to many other soft tissue tumors, genetics of smooth muscle tumors are poorly understood and such diagnostic testing is not yet generally applicable in this histogenetic group. Leiomyosarcomas are known to be genetically complex, often showing ‘chaotic’ karyotypes including aneuploidy or polyploidy, and no recurrent tumor-specific translocations have been detected.

Similar content being viewed by others

Smooth muscle hamartoma

There are (at least) two separate lesion types: one cutaneous and the other in the breast. Cutaneous smooth muscle hamartoma forms a small plaque-like, pigmented, sometimes hairy cutaneous lesion in young children, and the lesion is probably congenital in most cases. There is overlap with Becker’s nevus. Histologically there is a band-like infiltrate of mature pilar smooth muscle extending from dermis to the superficial subcutis (Figure 1).1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Smooth muscle hamartoma of the breast parenchyma entails bundles of non-atypical smooth muscle present within the breast parenchyma between the lobules, often along with fibrous stroma and scattered fat cells.10

Pilar (cutaneous) leiomyoma

This is a relatively rare skin tumor, which is often clinically painful. It occurs in adults of all ages with a wide site distribution. The most common sites of biopsies seem to be skin of upper extremities and trunk.

Pilar leiomyoma forms a poorly circumscribed, multinodular, or trabecular smooth muscle proliferation emanating from the arrector pili smooth muscle apparatus in the dermis (Figure 2). Multiple lesions are more common than solitary, except that solitary lesions seem to be more common in the genital and nipple area.11, 12 Histologically pilar leiomyomas may contain nuclear atypia but mitotic activity is exceptional. Mitotically active tumors with atypia have been traditionally classified as leiomyosarcomas. However, there is some tendency to ‘downgrade’ them as atypical smooth muscle tumors when purely dermally located, as such lesions do not have metastatic potential.13

Most cases with multiple lesions are associated with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) syndrome, which is caused by a fumarate hydratase (FH) gene loss-of-function germline mutation. This is coupled with a somatic loss of the other allele of FH in the tumor cells, and therefore FH behaves as a classic tumor suppressor gene, with bi-allelic inactivation causing the disease.14, 15, 16

Most HLRCC patients develop coalescent clusters and streaks of multiple pilar leiomyomas in the extremities or trunk at a relatively young age. Some tumors have atypical features by the presence of nuclear atypia and even some mitotic activity, but truly malignant behavior does not seem to be a clinical problem. However, these tumors can be troublesome as they are painful. Therefore, some patients are treated with experimental agents, such as botulinum toxin.17

Women with HLRCC syndrome typically develop multiple uterine leiomyomas of early onset, and this was already clinically observed much before the discovery of the HLRCC syndrome.18 HLRCC syndrome carries an estimated 15% lifetime risk for an aggressive renal cell carcinoma histologically corresponding to type 2 papillary carcinoma characterized by papillary or pseudorosette-forming architecture with variably eosinophilic cells with prominent nucleoli (Figure 3).19, 20 These tumors are notable for common nodal, abdominal, and distant visceral metastases.

Angioleiomyoma

This is the most common peripheral soft tissue leiomyoma typically occurring in the subcutis of extremities (especially lower leg), trunk wall, and less commonly head and neck. Some authors indicate that angioleiomyomas in the lower leg have a predilection to women.21 Angioleiomyoma is also clinically notable for often being painful.

Angioleiomyoma forms usually a small 1–2 cm homogeneous and well-circumscribed rubbery nodule. Histologically it is composed of eosinophilic smooth muscle cells intimately associated with the vein wall. The recognized variants are solid (very small lumens), venous (medium-size lumens), and cavernous (large lumens and thin smooth muscle elements in-between).20 The latter two variants may overlap with myopericytoma showing less complete smooth muscle differentiation.22, 23 Unusual morphologic patterns include fat infiltration (sometimes incorrectly designated angiomyolipoma), and focal calcification (Figure 4).24

Typical angioleiomyoma is positive for smooth muscle actin and desmin and negative for S100 protein.25 Some examples are positive for CD34, and this is especially true for those that are classified as myopericytomas.23

Differential diagnosis includes nerve sheath tumors and fibromas, with which angioleiomyomas are sometimes confused. Another pitfall is metastatic leiomyosarcoma, which can form well-demarcated subcutaneous nodules superficially resembling angioleiomyoma. Clues in identification of a metastatic tumor include multiplicity and presence of atypia and mitotic activity. A peculiar angioleiomyoma-like lesion can occur in the lymph node hilum, and this has been designated as angiomyomatous hamartoma of lymph node. These lesions have usually occurred in the inguinal area and occasionally in the neck.26, 27

Estrogen receptor-positive (Mullerian) leiomyomas in women

This is a special subcategory of histologically non-atypical smooth muscle tumors supposedly of Mullerian derivation that specifically occurs in women and is closely related to uterine leiomyoma, including the morphologic patterns. These tumors occur relatively commonly in the pelvis and parametria and were long ago likened to uterine leiomyomas and sometimes referred to as ‘parasitic leiomyomas’ under the assumption that they once were located in the uterus and subsequently became separated and reattached to adjacent structures. However, this is probably not the case, but rather their occurrence is a manifestation of peritoneal origination of smooth muscle tumors.

Reports of uterine type-leiomyomas elsewhere in the retroperitoneum date back >10 years.28, 29 Although specifically reported in the retroperitoneum, these tumors can also occur elsewhere in the abdomen in locations such as omentum, peritoneal surfaces, mesenteries, and in peri-intestinal or even in intestinal location. In the inguinal region, such leiomyomas may arise from the round ligament.30 Ocurrence in the abdominal wall is also possible. Retroperitoneal leomyomas can reach a very large size (several kilograms), whereas some present as small nodules. Similar tumors are also known in the external female genitalia.31, 32 The significance of the specific identification of this group includes the assumption that prognostic criteria for uterine smooth muscle tumors can be applied to this group.28, 29, 33 Retroperitoneal leiomyomas typically have mitoses <5/50 HPFs. Although higher counts are allowed in uterine smooth muscle tumors, there is no specific data on such tumors so that they should be approached with caution.

The histologic patterns of estrogen receptor-positive leiomyomas include those encountered in the uterus: solid, macro- and microtrabecular, and hyalinized. Lipoleiomyoma histology with focal mature adipose tissue component may also be encountered. Nuclear atypia is absent, and mitotic activity is very low, usually <5/50 HPFs, with general difficulty to find mitoses (Figure 5).

Immunohistochemical studies are positive for SMA, desmin, heavy caldesmon, and estrogen and usually also progesterone receptor (Figure 6), and contain nuclear WT1-immunoreactivity.

A special clinicopathologic variant of estrogen receptor-positive leiomyoma is peritoneal leiomyomatosis, in which innumerable small nodules of a few millimeters are present in the omentum or elsewhere on the peritoneal surfaces. This is a clinically indolent condition, which is sometimes associated with peritoneal endometriosis, sometimes coexisting in the same lesions. These tumors are often histologically composed of solid smooth muscle nodules without atypia, and mitotic figures are rare (Figure 7). Immunohistochemical features are similar to those of ER-positive leiomyomas (see below).34, 35

The differential diagnosis of ER-positive smooth muscle tumors includes PEComa and aggressive angiomyxoma. The former is at least focally HMB45-positive and the latter forms a dominant pelvic mass typically composed of oval cells that are positive for desmin and ER but often only focally if at all SMA-positive. Also, abdominal metastases of uterine leiomyosarcomas have to be considered. These usually display nuclear atypia and greater mitotic activity, and not infrequently, presence of multiple tumors as opposed to one. ER-positive primary retroperitoneal leiomyosarcoma is a rare possibility, and this is also recognized by atypia and mitotic activity.

Leiomyosarcoma of peripheral soft tissue

Smooth muscle tumors that contain both nuclear atypia and mitotic activity are generally designated leiomyosarcomas to denote their malignant (metastatic) potential. An exception to this rule is purely cutaneous (dermal) leiomyosarcoma that does not have significant metastatic potential.13, 36, 37, 38 Some authors more recently have designated such tumors ‘atypical smooth muscle tumors’ noting that they had a 30% local recurrence rate but developed no metastases.13 However, subcutaneous extension should not be accepted for these cutaneous tumors, as this is already known to introduce metastatic potential. At any rate, complete excision with negative margins is necessary also for the dermal tumors, as they may otherwise progress into metastasizing tumors. There has been sometimes a quest for more accurate prediction (eg, plotting mitotic rate with recurrences/metastases), but very small sample size in most series of soft tissue leiomyosarcomas has hampered that effort. A great majority of soft tissue leiomyosarcomas are high or intermediate grade, and low-grade tumors are rare.

Series of peripheral soft tissue leiomyosarcomas have noted that subcutaneous leiomyosarcomas have a metastatic rate varying from 0 to 39%.39, 40, 41, 42 The largest recent series from the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group showed a metastatic rate of 20% for subcutaneous and 60% for deep intramuscular leiomyosarcomas.42 Tumors with lower mitotic rates may show longer recurrence-free survivals. Disruption of tumor (previous partial surgery) was found an adverse factor in one series.41 It is likely that many peripheral (non-cutaneous, non-retroperitoneal) leiomyosarcomas arise from vascular smooth muscle, although it is difficult to observe vascular origin in practice. Gross origin of tumor from a vein wall has been noted two small series.43, 44 One series detected venous origin microscopically in 90% of cases.41

Histologically, leiomyosarcoma shows a smooth muscle-like appearance, being composed of irregularly intersecting fascicles of spindled cells with variably eosinophilic cytoplasm and variable mitotic activity (Figure 8a). Focal pleomorphism is common even in low-grade tumors with low mitotic activity (Figure 8b). In some cases, this eosinophilic cytoplasm is clumped to form so-called contraction bands.45 Nuclei are typically blunt-ended, ‘cigar-shaped’. These histologic features are sufficient for the recognition of most leiomyosarcomas. In rare cases, leiomyosarcoma can undergo pleomorphic evolution (‘dedifferentiation’) so that specific diagnosis can be difficult unless differentiated component is also recognized (Figure 8c and d). This evolution is more common in retroperitoneal tumors that typically reach a larger size than the peripheral examples.40, 46

Examples of leiomyosarcoma. (a) Example composed of uniform cells with blunt-ended nuclei with mild general atypia and high mitotic activity. (b) Focal nuclear pleomorphism is a common feature even in low-grade tumors. (c) Example with transition into a pleomorphic sarcoma (‘dedfifferentiated leiomyosarcoma’). (d) Extensively pleomorphic leiomyosarcoma, which would be difficult to recognize unless for differentiated areas elsewhere in the tumor.

Immunohistochemically, leiomyosarcomas are almost invariably and strongly positive for α-smooth muscle actin, but SMA-positivity alone is not sufficient as myofibroblastic tumors (nodular fasciitis, myofibroblastic sarcomas) are also positive. A good majority (70–80%) are also positive for desmin. Most cases are positive for heavy-caldesmon and smooth muscle myosin. The latter two markers can be useful in the differential diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma and myofibroblastic sarcomas, because the latter are negative for heavy caldesmon and smooth muscle myosin.47, 48 Occurrence of keratin- and EMA-positive cells should not lead into the diagnosis of carcinoma; two studies have found these in 40–60% of leiomyosarcomas.49, 50

Genetically, leiomyosarcomas are complex with no recurrent translocations and have large numbers of copy number alterations in comparative genomic hybridization studies.51 A common finding is loss of retinoblastoma protein.52 There is also an association between retinoblastoma syndrome and leiomyosarcoma, which seems to be the most common sarcoma in retinoblastoma survivors.53 Similarly, leiomyosarcomas often show loss of functional p53 and are associated with TP53/p53 germline mutations (Li-Fraumeni syndrome).

Retroperitoneal leiomyosarcoma

Being pathologically essentially similar to peripheral leiomyosarcoma, retroperitoneal tumors are clinically distinctive but have been frequently intermixed with GISTs in the older series so that only few pure series exist.54 Our AFIP experience showed that there are more GISTs in the retroperitoneum than true leiomyosarcomas. In general, immunohistochemical presence of KIT and Ano-1/DOG1 and absence of desmin help to identify GIST, but SMA and h-caldesmon can be present in both smooth muscle tumors and GIST.

Retroperitoneal leiomyosarcoma often arises from larger veins, most commonly inferior vena cava and sometimes from the renal or iliac veins. Tumors with intraluminal involvement of middle segment of inferior vena cava are often complicated by vascular compromise of liver (Budd-Chiari syndrome) and have a worse prognosis. In addition, large tumor size is also an adverse prognostic factor. In general, the prognosis of leiomyosarcomas of inferior vena cava55, 56, 57, 58, 59 and other retroperitoneum is poor.54 Tumors with lower mitotic rates (1-2/10 HPFs) may have longer survivals (10+ years in some cases) but in our experience often develop late metastases, nevertheless.

Smooth muscle tumors of soft tissue of uncertain biologic potential

This is a practical designation and not a biologic entity reflecting situations where definitive determination of biologic potential cannot be made. Usually, this is due to limited sampling with insufficient opportunity to detect diagnostic criteria such as atypia or mitotic activity, and therefore malignancy cannot be excluded in the context. In some cases, soft tissue smooth muscle tumors can have conflicting diagnostic features that lead to similar conclusion (eg, tumors with no or low atypia with significant mitotic activity). As there are far fewer such soft tissue tumors than uterine ones, the diagnostic criteria predictive for malignancy are not equally developed. Similar rationale applies to other visceral smooth muscle tumors.

Gastrointestinal smooth muscle tumors

Although most mesenchymal tumors in the GI tract are now classified as GISTs rather than smooth muscle tumors, true leiomyoma occurs in all segments of the GI tract in two forms: mural and muscularis mucosae.

Mural leiomyoma involves gut wall and is most common in the esophagus, where it is five times or more common than GIST. These tumors vary from small nodules to large masses >10–15 cm. Mural leiomyomas are rare in the stomach and small intestine (1 for every 50 GISTs). GI leiomyomas occur in all ages but often in younger patients than GISTs.60, 61, 62 Most of them are sporadic but they occur in connection with two rare familial syndromes.

Alport syndrome is a basement membrane defect (mutated collagen type 4), also associated with hearing loss and renal disease. Alport syndrome-associated esophageal leiomyomas may already manifest in childhood and occur in siblings.63, 64, 65 Interestingly, similar somatic changes involving collagen 4 gene have also been detected in sporadic esophageal leiomyomas indicating that disruption of basement membrane collagen may be related their pathogenesis.66

Even rarer syndrome associated with GI mural leiomyoma is multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (also known as Werner syndrome, with pituitary, parathyroid, and pancreatic/duodenal neuroendocrine tumors, with mutated MEN1 tumor-suppressor gene). In addition, these MEN-1 patients can have multiple cutaneous fibromas (somewhat reminiscent but distinctive from usual dermatofibromas).67

Histologically, GI leiomyomas are composed randomly oriented or fascicularly organized eosinophilic smooth muscle cells. These often contain cytoplasmic globoid inclusions that are positive for desmin (Figure 9). Focal atypia may occur, but mitoses are exceptional if they occur. If both nuclear atypia and mitoses occur, it is appropriate to designate these tumors either smooth muscle tumors of uncertain biologic potential or low-grade leiomyosarcomas.

Immunohistochemically, typical is the presence of full complement of smooth muscle cell antigens (SMA, desmin, and h-caldesmon). The tumor cells are negative for KIT, but caveat in differential diagnosis from GISTs is that some GI leiomyomas are colonized by KIT-positive Cajal cells that can be moderately numerous, although always as a minority population among the smooth muscle component (Figure 10).

Muscularis mucosae leiomyomas usually occur in the colon and rectum, where these tumors are far more common than GISTs. They exceptionally occur in the small intestine but almost never in the stomach. These leiomyomas form small, usually <1 cm, polypoid mucosal lesions that can rarely approach 2 cm in diameter. Histologically they are composed of mature smooth muscle and have continuity with muscular mucosae layer (Figure 11). The immunohistochemical profile is similar to that of soft tissue leiomyomas.68

GI leiomyosarcoma is far less common than GIST. These tumors occur in all segments of the GI tract, although they are extremely rare in the esophagus and stomach. In the small intestine, their frequency seems to be 1 for every 30 GISTs, although in the colon and rectum their relative frequency to GIST is higher 1:10. Most GI leiomyomas form polypoid intraluminal masses of a few cm in diameter. Some form extensive transmural masses.69, 70, 71

Most GI leiomyosarcomas are high-grade tumors with mitotic rate frequently ranging 50–100/50 HPFs. Nevertheless, smaller tumors have a relatively good prognosis, better than GISTs with similar mitotic rates. Tumors with low mitotic rates are rare so that there are limited data on their behavior. However, such tumors have at least potential to recur, although distant metastases have not been reported.71

GIST is the first differential diagnosis. Eosinophilic cytoplasm, immunohistochemical presence of smooth muscle markers, and absence of KIT and Ano1-/DOG1 are a good diagnostic help in problem cases to support a smooth muscle tumor. When multiple leiomyosarcomas are present, then the possibility of metastasis from another source has to be considered. EBV-associated tumor has to be kept in mind in AIDS and post-transplant patients (these are EBER-positive).

Other visceral smooth muscle tumors

Leiomyomas can occur in a wide variety of internal locations, although they are rare. One of them is bronchial leiomyoma, which is usually a small, clinically indolent well-demarcated smooth muscle nodule originating from the smooth muscle components of the bronchial wall.72

Benign metastasizing leiomyoma is a term for often multiple, clinically indolent pulmonary tumors that occur in women with previous uterine or extrauterine ER/PR-dependent smooth muscle tumors. They are histologically generally similar to cellular uterine leiomyomas and are immunohistochemically positive for desmin, SMA, and estrogen receptor. Their genetic profile seems to be similar to uterine leiomyomas in that they often contain rearrangements of the HMGA1 locus (at 6p21) and have losses in chromosome 7q.73, 74

In the urinary bladder, both benign smooth muscle tumors (leiomyomas) and leiomyo-sarcomas occur, and these are distinguished by the presence of atypia and any mitotic activity in the latter. Leiomyosarcomas seem to be almost twice more common than leiomyomas. Lower mitotic activity (and lower grade) of leiomyosarcomas correlate with a less aggressive behavior.75

Leiomyosarcomas have been reported in almost all visceral sites although in small numbers. They may arise from vessel (vein) walls of practically any organ-based location. For example, renal parenchymal leiomyosarcomas may be of renal vein origin and clinicopathologically these tumors are probably closely related to retroperitoneal leiomyosarcomas. Criteria for identifying malignant potential are similar to those applied for smooth muscle tumors of soft tissues.

Visceral (especially liver, lung also and also osseous) occurrence of a smooth muscle tumor should prompt consideration of metastasis from another source. In women, history of uterine tumor may be a diagnostic clue, and some metastases retain ER expression supporting uterine origin. The possibility of EBV-associated smooth muscle tumor has to be considered especially in post-transplant and AIDS patients.

EBV-associated smooth muscle tumors

This is a special, rare subset of smooth muscle tumors that occur in immunosuppressed individuals. Traditionally, the condition has been more common in AIDS patients, and a minority of patients has been solid organ transplant recipients (liver, kidney, heart). Many of the AIDS patients are young, including children, whereas the organ transplant recipients are usually middle-aged adults. The smooth muscle tumors can occur in peripheral soft tissue, intracranial space, or visceral sites, and tumor multiplicity is common.76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85 Molecular genetic analysis has shown that multiple tumor represent independent clones rather than dissemination of a single neoplastic clone.85 In multiple tumor cases, tumors arising in the transplant are of donor cell origin, whereas those at the other sites arise from recipient cells, which also points to polyclonal origin of multiple tumors.82

Although these tumors were originally divided into EBV-associated leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas, current classification holds them all collectively as smooth muscle tumors as they are usually indolent although somewhat unpredictable in behavior. True metastatic behavior is rare, and was observed only in 4 of 51 AIDS-associated (8%)77 and 1 of 19 cases (5%) in a mixed AIDS and transplantation-associated series.85 Based on a large survey of AIDS-associated cases, mitotic rate does not seem to distinguish cases with malignant outcome.77

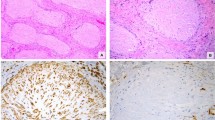

Histologically, the EBV-associated smooth muscle tumors have a spectrum from a well-differentiated conventional-appearing spindle cell smooth muscle tumors to those composed of ovoid cells with incomplete smooth muscle differentiation (Figure 12). Intratumoral T lymphocytes may be present and even be prominent, but this is not a uniform feature. These tumors are smooth muscle actin positive but often desmin negative. Some have also been classified as myoperi-cytomas reflecting differentiation intermediate to smooth muscle cell and pericyte.86 A diagnostic test is demonstration of EBV RNA by in situ hybridization, which highlights the tumor cell nuclei (Figure 12).

EBV-associated smooth muscle tumor. (a) This tumor forms an eccentric intramural appendiceal mass. (b) These smooth muscle tumors are often composed of oval cells that appear less mature than typical smooth muscle cells. The tumor cells are positive for SMA but only variably positive for desmin. Nuclear positivity for Epstein–Barr virus RNA is a typical finding.

Conclusion

Smooth muscle tumors of soft tissues and non-uterine visceral organs can be largely separated into leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas. The latter group refers to tumors with both nuclear atypia and mitotic activity denoting potential for metastasis (purely cutaneous tumors may be exceptions in lacking metastatic potential). The designation ‘smooth muscle tumor of uncertain biologic potential’ is appropriate in small specimens and when facing conflicting criteria. Estrogen receptor-positive (Mullerian-type) non-atypical smooth muscle tumors can occur in women anywhere in the abdomen and abdominal wall and generally behave in a benign manner even if the tumor is large. Epstein–Barr virus-associated smooth muscle tumors are a special group of neoplasms associated with immunosuppression (AIDS, post-transplant immunosuppression). These tumors generally have a low biologic potential and involve both peripheral soft tissues and viscera, sometimes forming multiple independent tumors and often showing incomplete smooth muscle differentiation. Demonstration of EBV-RNA (EBER) is their typical diagnostic feature.

References

Urbanek RW, Johnson WC . Smooth muscle hamartomas associated with Becker’s nevus. Arch Dermatol 1978;114:104–106.

Berger TG, Levin MW . Congenital smooth muscle hamartoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 1984;11:709–712.

Slifman NR, Harrist TJ, Rhodes AR . Congenital arrector pili hamartoma. A case report and review of the spectrum of Becker’s melanosis and pilar smooth-muscle hamartoma. Arch Dermatol 1985;121:1034–1037.

Johnson MD, Jacobs AH . Congenital smooth muscle hamartoma. A report of six cases and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol 1989;125:820–822.

Zvulunov A, Rotem A, Merlob P et al. Congenital smooth muscle hamartoma. Prevalence, clinical findings, and follow-up in 15 patients. Am J Dis Child 1990;144:782–784.

Gagne EJ, Su WP . Congenital smooth muscle hamartoma of the skin. Pediatr Dermatol 1993;10:142–145.

Grau-Massanes M, Raimer S, Colome-Grimmer M et al. Congenital smooth muscle hamartoma presenting as a linear atrophic plaque: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol 1996;13:222–225.

Jang HS, Kim MB, Oh CK et al. Linear congenital smooth muscle hamartoma with follicular spotted appearance. Br J Dermatol 2000;142:138–142.

Gualandri L, Cambiaghi S, Ermacora E et al. Multiple familial smooth muscle hamartomas. Pediatr Dermatol 2001;18:17–20.

Daroca PJ Jr, Reed RJ, Love GL et al. Myoid hamartomas of the breast. Hum Pathol 1985;16:212–219.

Fisher WC, Helwig EB . Leiomyomas of the skin. Arch Dermatol 1963;88:78–88.

Raj S, Calonje E, Kraus M et al. Cutaneous pilar leiomyoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 53 lesions in 45 patients. Am J Dermatopathol 1997;19:2–9.

Kraft S, Fletcher CD . Atypical intradermal smooth muscle neoplasms: clinicopathologic analysis of 84 cases and reappraisal of cutaneous ‘leiomyosarcoma’. Am J Surg Pathol 2011;35:599–607.

Kiuru M, Launonen V, Hietala M et al. Familial cutaneous leiomyomatosis is a two-hit condition associated with renal cell cancer of characteristic histology. Am J Pathol 2001;159:825–829.

Alam NA, Rowan AJ, Wortham NC et al. Genetic and functional analyses of FH mutations in multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomatosis, hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cancer, and fumarate hydratase deficiency. Hum Mol Genet 2003;159:825–829.

Toro RJ, Nickerson ML, Wei MH et al. Mutations in the fumarate hydratase gene cause hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer in families in North America. Am J Hum Genet 2003;73:95–106.

Sifaki MK, Krueger-Krasagakis S, Kotsopuolos A et al. Botulinum toxin type A-treatment of a patient with multiple cutaneous piloleiomyomas. Dermatology 2009;218:44–47.

Knoth W, Knoth-Born RC . Familial utero-cutaneous leiomyomatosis. Z Haut Geschlechtskr 1964;37:191–206.

Sudarshan S, Linehan WM . Genetic basis of cancer of the kidney. Semin Oncol 2006;33:544–551.

Merino MJ, Torres-Cabala C, Pinto P et al. The morphologic spectrum of kidney tumors in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC) syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:1578–1585.

Hachisuga T, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M . Angioleiomyoma. A clinicopathologic reappraisal of 562 cases. Cancer 1984;54:126–130.

Granter SR, Badizadegan K, Fletcher CD . Myofibromatosis in adults, glomangiopericytoma, and myopericytoma: a spectrum of tumors showing perivascular myoid differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol 1998;22:513–525.

Matsuyama A, Hisaoka M, Hashimoto H . Angioleiomyoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical reappraisal with special reference to the correlation with myopericytoma. Hum Pathol 2007;38:645–651.

Beer TW . Cutaneous angiomyolipomas are HMB45 negative, not associated with tuberous sclerosis, and should be considered as angioleiomyomas with fat. Am J Dermatopathol 2005;27:418–421.

Fox SB, Heryet A, Khong TY . Angioleiomyomas: an immunohistochemical study. Histopathology 1990;16:495–496.

Chan JKC, Frizzera G, Fletcher CDM et al. Primary vascular tumors of lymph nodes other than Kaposi’s sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1992;16:335–350.

Laeng RH, Hotz MA, Borisch B . Angiomyomatous hamartoma of a cervical lymph node combined with hemangiomatosis and vascular transformation of sinuses. Histopathology 1996;29:80–84.

Billings SD, Al Folpe, Weiss SW . Do leiomyomas of deep soft tissue exist? An analysis of highly differentiated smooth muscle tumors of deep soft tissue supporting two distinct subtypes. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:1134–1142.

Paal E, Miettinen M . Retroperitoneal leiomyomas. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 56 cases with a comparison to retroperitoneal leiomyosarcomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:1355–1363.

Patil DT, Laskin WB, Fetsch JF et al. Inguinal smooth muscle tumors in women—a dichotomous group consisting of Mullerian type leiomyomas and soft tissue leiomyosarcomas: an analysis of 55 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2011;35:315–324.

Tavassoli FA, Norris HJ . Smooth muscle tumors of the vulva. Obstetr Gynecol 1979;53:213–217.

Nielsen GP, Rosenberg AE, Koerner FC et al. Smooth-muscle tumors of the vulva. A clinicopathological study of 25 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 1996;20:779–793.

Bell SW, Kempson RL, Hendrickson MR . Problematic uterine smooth muscle neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol 1994;18:535–558.

Tavassoli FA, Norris HJ . Peritoneal leiomyomatosis (Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata): A clinicopathologic study of 20 cases with ultrastructural observations. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1982;1:59–74.

Bekkers RL, Willemsen WN, Shijf CP et al. Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata: does malignant transformation occur. A literature review. Gynecol Oncol 1999;75:158–163.

Bernstein SC, Roenigk RK . Leiomyosarcoma of the skin. Treatment of 34 cases. Dermatol Surg 1996;22:631–635.

Kaddu S, Beham A, Cerroni L et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1997;21:979–987.

Jensen ML, Jensen OM, Michalski W et al. Intradermal and subcutaneous leiomyosarcoma: A clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 41 cases. J Cutan Pathol 1996;23:458–463.

Gustafson P, Willen H, Baldetrop B et al. Soft tissue leiomyosarcoma. A population-based epidemiologic and prognostic study of 48 patients, including cellular DNA content. Cancer 1992;70:114–119.

Hashimoto H, Daimaru Y, Tsuneyoshi M et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the external soft tissues. A clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and electron microscopic study. Cancer 1986;57:2077–2088.

Farshid G, Pradham M, Goldblum J et al. Leiomyosarcoma of somatic soft tissues. A tumor of vascular origin with multivariate analysis of outcome in 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:14–24.

Svarvar K, Böhling T, Berlin Ö et al. Clinical course of nonvisceral soft tissue leiomyosarcoma in 225 patients from the Scandinavian sarcoma group. Cancer 2007;109:282–291.

Varela-Duran J, Oliva H, Rosai J . Vascular leiomyosarcoma: the malignant counterpart of vascular leiomyoma. Cancer 1979;44:1684–1691.

Berlin O, Stener B, Kindblom LG et al. Leiomyosarcoma of venous origin in the extremities. A correlated clinical, roentgenologic, and morphologic study with diagnostic and surgical implications. Cancer 1984;54:2147–2159.

Venance SL, Burns KL, Veinot JP et al. Contraction bands in visceral and vascular smooth muscle. Hum Pathol 1996;27:1035–1041.

Chen E, O’Connell F, Fletcher CD . Dedifferentiated leiomyosarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 18 cases. Histopathology 2011;59:1135–1143.

Watanabe K, Kusakabe T, Hoshi N et al. H-caldesmon in leiomyosarcoma and tumors with smooth muscle cell differentiation: its specific expression in the smooth muscle tumor. Hum Pathol 1999;30:392–396.

Perez-Montiel MD, Plaza JA, Dominguez-Malagon H et al. Differential expression of smooth muscle myosin, smooth muscle actin, H-caldesmon, and calponin in the diagnosis of myofibroblastic and smooth muscle lesions of skin and soft tissue. Am J Dermatopathol 2006;28:105–111.

Miettinen M . Immunoreactivity for cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen in leiomyosarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1988;112:637–640.

Iwata J, Fletcher CD . Immunohistochemical detection of cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen in leiomyosarcoma: a systematic study of 100 cases. Pathol Int 2000;50:7–14.

Sandberg AA . Updates on the cytogenetics and molecular genetics of bone and soft tissue tumors: leiomyosarcoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2005;161:1–19.

Stratton MR, Williams S, Fisher C et al. Structural alterations of the RB1 gene in human soft tissue tumours. Br J Cancer 1989;60:202–205.

Kleinerman RA, Tucker MA, Abramson DH et al. Risk of soft tissue sarcomas by individual subtype in survivors of hereditary retinoblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007;99:24–31.

Rajani B, Smith TA, Reith JD et al. Retroperitoneal leiomyosarcomas unassociated with the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathologic analysis of 17 cases. Mod Pathol 1999;12:21–28.

Mingoli A, Cavallaro A, Sapienza P et al. International registry of inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma: analysis of a world series on 218 patients. Anticancer Res 1996;16:3201–3205.

Hines OJ, Nelson S, Quinones-Baldrich WJ et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: prognosis and comparison with leiomyosarcoma of other anatomic sites. Cancer 1999;85:1077–1083.

Hollenbeck ST, Grobmyer SR, Kent KC et al. Surgical treatment and outcomes in patients with primary inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma. J Am Coll Surg 2003;197:575–579.

Ito H, Hornick JL, Bertagnolli MM . et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: Survival after aggressive management. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:3534–3541.

Laskin WB, Fanburg-Smith JC, Burke AP et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: clinicopathologic study of 40 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:873–881.

Seremetis MG, Lyons WS, de Guzman VC et al. Leiomyomata of the esophagus. An analysis of 838 cases. Cancer 1976;38:2166–2177.

Miettinen Sarlomo-Rikala MSobin, Lasota J . Esophageal stromal tumors—a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular genetic study of seventeen cases and comparison with esophageal leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;23:121–132.

Hatch GF III, Wertheimer-Hatch L, Hatch KF et al. Tumors of the esophagus. World J Surg 2000;24:401–411.

Lonsdale RN, Roberts PF, Vaughan R et al. Familial oesophageal leiomyomatosis and nephropathy. Histopathology 1993;20:127–133.

Ueki Y, Naito I, Oohashi T et al. Topoisomerase I and II consensus sequences in a 17-kb deletion junction of the COL4A5 and COL4A6 genes and immunohistochemical analysis of esophageal leiomyomatosis associated with Alport syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 1998;62:253–261.

Ueki Y, Naito I, Oohashi T et al. Topoisomerase I and II consensus sequences in a 17-kb deletion junction of the COL4A5 and COL4A6 genes and immunohistochemical analysis of esophageal leiomyomatosis associated with Alport syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 1998;62:253–261.

Heidet L, Boye E, Cai Y et al. Somatic deletion of the 5’ ends of both the COL4A5 and COL4A6 genes in a sporadic leiomyoma of the esophagus. Am J Pathol 1998;152:673–678.

McKeeby JL, Li X, Vortmeyer AO et al. Multiple leiomyomas of the esophagus, lung, and uterus in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Am J Pathol 2001;159:1121–1127.

Miettinen M, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Sobin LH . Mesenchymal tumors of muscularis mucosae of colon and rectum are benign leiomyomas that should be separated from gastrointestinal stromal tumors – a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 88 cases. Mod Pathol 2001;14:950–956.

Miettinen M, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Sobin LH et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors and leiomyosarcoma in the colon: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 44 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:1339–1352.

Miettinen M, Furlong M, Sarlomo-Rikala M et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors, intramural leiomyomas, and and leiomyosarcomas in the rectum and anus: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular genetic study of 144 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:1121–1133.

Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Lasota J . True smooth muscle tumors of the small intestine: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 25 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:430–436.

Park JS, Lee M, Kim HK et al. Primary leiomyoma of the trachea, bronchus, and pulmonary parenchyma-a single-institutional experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012;41:41–45.

Nuovo GJ, Schmittgen TD . Benign metastasizing leiomyoma of the lung: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and micro-RNA analyses. Diagn Mol Pathol 2008;17:145–150.

Bowen JM, Cates JM, Kash S et al. Genomic imbalances in benign metastasizing leiomyoma: characterization by conventional karyotypic, fluorescence in situ hybrid-ization, and whole genome SNP array analysis. Cancer Genet 2012;205:249–254.

Martin SA, Sears DL, Sebo TJ et al. Smooth muscle neoplasms of the urinary bladder: a clinicopathologic comparison of leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:292–300.

McClain KL, Leach CT, Jenson HB et al. Association of Epstein-Barr virus with leiomyosarcomas in children with AIDS. N Engl J Med 1995;332:12–18.

Purgina B, Rao UN, Miettinen M et al. AIDS-related EBV-associated smooth muscle tumors: A review of 64 published cases. Patholog Res Int 2011;2011:561548.

Ross JS, Del Rosario A, Bui HX et al. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma in a child with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Hum Pathol 1992;23:69–72.

Orlow SJ, Kamino H, Lawrence RL . Multiple subcutaneous leiomyosarcomas in an adolescent with AIDS. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 1992;14:265–268.

van Hoeven KH, Factor SM, Kress Y et al. Visceral myogenic tumors. A manifestation of HIV infection in children. Am J Surg Pathol 1993;17:1176–1181.

Litofsky NS, Pihan G, Corvi F et al. Intracranial leiomyosarcoma: a neuro-oncological consequence of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Neurooncol 1998;40:179–183.

Timmons CF, Dawson DB, Richards CS et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated leiomyosarcomas in liver transplantation recipients. Origin from either donor or recipient tissue. Cancer 1995;76:1481–1489.

Somers GR, Tesoriero AA, Hartland E et al. Multiple leiomyosarcomas of both donor and recipient origin arising in heart-lung transplant patient. Am J Surg Pathol 1998;22:1423–1428.

Rogatsch H, Bonatti H, Menet A et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated multicentric leiomyosarcoma in an adult patient after heart transplantation: case report and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:614–621.

Deyrup AT, Lee VK, Hill CE et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated smooth muscle tumors are distinctive mesenchymal tumors reflecting multiple infection events. A clinicopathologic and molecular analysis of 29 tumors from 19 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30:75–82.

Lau PP, Wong OK, Lui PC et al. Myopericytoma in patients with AIDS: a new class of Epstein-Barr virus-associated tumor. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:1666–1672.

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported as a part of NCI’s intramural research program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miettinen, M. Smooth muscle tumors of soft tissue and non-uterine viscera: biology and prognosis. Mod Pathol 27 (Suppl 1), S17–S29 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2013.178

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2013.178

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Natural history of gastric leiomyoma

Surgical Endoscopy (2024)

-

Top Ten Differentials to Mull Over for Head and Neck Myoepithelial Neoplasms

Head and Neck Pathology (2023)

-

Endoluminal Leiomyoma of the Gastric Antrum: a Report of a Rare Case

Journal of Gastrointestinal Cancer (2023)

-

Multifocal EBV-associated smooth muscle tumors in a patient with cytomegalovirus infection after liver transplantation: a case report from Shiraz, Iran

Diagnostic Pathology (2022)

-

Sarcomas of the sellar region: a systematic review

Pituitary (2021)