Abstract

ERG gene encodes for an Ets family regulatory transcription factor and is involved in recurrent chromosomal translocations found in a subset of acute myeloid leukemias, prostate carcinomas and Ewing sarcomas. The purpose of this study was to examine the utility of an ERG antibody to detect EWSR1-ERG rearranged Ewing sarcomas. A formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue microarray and whole-tissue sections from 32 genetically characterized Ewing sarcomas were examined: 22 with EWSR1-FLI1, 8 with EWSR1-ERG and 2 with EWSR1-NFATC2. Immunohistochemistry was performed using a rabbit anti-ERG monoclonal antibody directed against the C-terminus of the protein and a mouse anti-FLI1 monoclonal antibody against a FLI1 Ets domain (C-terminus) fusion protein. Immunoreactivity was graded for extent and intensity of positive tumor cell nuclei. ERG labeling was seen in 7/8 EWSR1-ERG cases (predominantly diffuse (5+), moderate to strong), while only 3/24 non-EWR1-ERG cases showed labeling (very weak). FLI1 labeling was observed in 29/31 cases regardless of fusion variant; 23 displayed diffuse (5+) strong/moderate labeling (5/7 EWSR1-ERG, 18/22 EWSR1-FLI1). Both EWSR1-NFATC2 cases had weak reactivity with FLI1 and weak or no reactivity for ERG. In conclusion, strong nuclear ERG immunoreactivity is specific for Ewing sarcomas with EWSR1-ERG rearrangement. In contrast, FLI1 was not specific to rearrangement type, likely because of cross reactivity with the highly homologous Ets DNA-binding domain present in the C-terminus of both ERG and FLI1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Ewing sarcoma is characterized by a recurrent translocation involving EWSR1 on 22q12. The most frequent partner is FLI1 located on 11q22, occurring in ∼85% of cases.1, 2, 3 However, a minority of tumors will harbor a translocation involving EWSR1 and an alternative partner, the most common of which is ERG located on 21q12.2, 3, 4 These characteristic translocations result in the constitutive expression of an abnormal transcription factor that is critical for Ewing sarcoma tumorigenesis, and is composed of the amino end of EWSR1, a potent transcriptional activator, and the C-terminus of FLI1/ERG that contains the Ets DNA-binding domain. Both FLI1 and ERG belong to the Ets family of transcription factors, which regulate several genes involved in cellular differentiation and growth.2, 5 Chimeric variants of EWSR1 with other Ets genes, including ETV4 and FEV, have been described but are very rare.6 Rearrangements of EWSR1 with non-Ets family genes, including NFATc2, POU5F1, SMARCA5, ZSG and SP3, are also rare.2, 6, 7, 8

ERG is also found to be involved in recurrent translocations in other tumors including prostate carcinoma and some acute myeloid leukemias. Up to 70% of prostate carcinomas harbor a translocation involving ERG and TMPRSS2, a gene located on chromosome 21q22 and encodes for an androgen dependent transmembrane protease. This chimeric protein is believed to be important to prostate carcinogenesis, and is found in the early precursor lesion prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Chimeric variants with other Ets family members can exist, and the same tumor can even harbor multiple fusion variants.9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Translocations and deletions of ERG are also seen in some acute myeloid leukemias and ERG overexpression has been associated with poor prognosis.14, 15

In addition, ERG is involved in the development of both hematopoietic and endothelial cells. ERG has a critical function in normal hematopoiesis.16, 17 It is also constitutively expressed in normal endothelial cells and regulates angiogenesis and endothelial apoptosis.18, 19, 20

Several studies have shown anti-ERG antibody useful for prostate carcinoma, metastatic and primary, and prostatic intraepithelial neoplasias.10, 11, 12, 21, 22 The detection of ERG is highly correlated with both ERG rearrangement by fluorescence in-situ hybridization and with ERG mRNA overexpression.10, 12, 21 Similar to FLI1, ERG is also found to be expressed in both benign and malignant vascular tumors serving as a helpful marker for endothelial differentiation.11, 23, 24 However, anti-ERG antibody use with Ewing sarcoma has not been previously reported.

The purpose of our study was to examine the utility of an anti-ERG antibody-specific for the C-terminus to identify ERG rearrangement in Ewing sarcoma. Given that FLI1 and ERG share significant homology, a comparison with a commercially available FLI1 antibody was also made.

Materials and methods

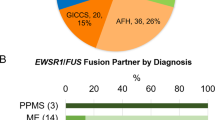

Thirty-two cases of genetically characterized (fusion transcript known) Ewing sarcoma were selected from the pathology files of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Texas Children's Hospital/Baylor College of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Leiden University Medical Center. Appropriate immunohistochemical studies were performed and all cases were histologically reviewed by experienced sarcoma pathologists. Five-micron thick unstained slides were prepared from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded whole-tissue sections in 19 cases and from a tissue-microarray containing 14 cases. Molecular characterization was previously determined by RT-PCR and verified with sequencing using standard laboratory techniques depending on the institution.4, 25 The distribution included 22 with EWSR1-FLI1, 8 with EWSR1-ERG and 2 with EWSR1-NFATC2.

Immunohistochemistry was performed following pressure cooker antigen retrieval using a rabbit anti-ERG monoclonal antibody directed against the last 30 amino acids of the C-terminus (1:2000; EPR3864(2); Epitomics), a mouse anti-FLI1 monoclonal antibody raised against a bacterially expressed FLI1 Ets domain fusion protein (1:100; G146-222; BD Biosciences) and the Envision Plus detection system (Dako). The extent of immunoreactivity was graded according to the percentage of positive tumor cell nuclei (0, no staining; 1+, <5%; 2+, 5–25%; 3+, 26–50%; 4+, 51–75%; and 5+, 76–100%), and the intensity of staining was graded as weak, moderate, or strong.

All cases were handled according the ethical rules of each institution and processed in an anonymous coded fashion.

Results

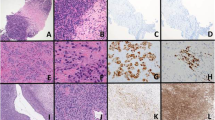

ERG labeling of tumor nuclei was seen in 7/8 EWSR1-ERG cases (diffuse (5+) moderate to strong), while only 3/24 non-EWR1-ERG cases showed labeling (2–4+, weak). See Table 1 and Figures 1, 2, 3. FLI1 labeling of tumor nuclei was observed in 29 of 31 cases with available material, and was seen in the majority of tumors regardless of fusion variant; 23 tumors displayed diffuse (5+) strong to moderate FLI1 labeling (5/7 EWSR1-ERG, 18/22 EWSR1-FLI1). Both EWSR1-NFATC2 cases had 4+ to 5+ weak reactivity with FLI1 and 4+ weak to no reactivity for ERG.

Case 17. Example of Ewing Sarcoma with EWSR1-FLI1. Diffuse (5+) moderate labeling for (a) FLI1 seen with (b) significant (4+) but weak labeling for ERG. Only ERG-rearranged cases showed strong or moderate nuclear immunoreactivity for ERG. Strong labeling of endothelial cells is present as positive-internal control.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the specificity of an anti-ERG antibody in a series of molecularly characterized Ewing Sarcoma. We demonstrate that in Ewing sarcoma the antibody to the C-terminus of Erg is relatively specific (88%) and sensitive (88%) for ERG rearrangement. In our series, diffuse (5+) moderate-to-strong nuclear labeling was present in seven of eight tumors carrying an ERG rearrangement. The positive predictive value of diffuse (5+) or strong to moderate labeling with anti-ERG for ERG rearrangement in Ewing sarcoma was 100%. In contrast, the three cases which were reactive for ERG but lacked ERG rearrangement had only weak expression. This finding may provide additional support for Ewing sarcoma in appropriate situations (immunohistochemical, histological and clinical) when molecular confirmation is not available. Our findings are analogous to other studies examining the utility of anti-ERG antibodies in prostatic carcinomas with ERG rearrangement. Park et al10 found 88 out of 92 tumors with ERG rearrangement expressed ERG, while only 4 cases of out 116 non-ERG rearranged carcinomas expressed ERG. The overall sensitivity was 96% and specificity was 97%. Falzarano et al21 observed a similar high sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 99% in ERG-rearranged prostate carcinomas. In their study, 99 out of 103 tumors with ERG rearrangement expressed ERG, while only one out of 202 tumors negative for ERG rearrangement expressed ERG.21 A comparably high sensitivity (100%) and specificity (85%) was seen in ERG mRNA overexpression and ERG expression in van Leender et al12study of 41 prostatic adenocarcinomas. These findings support the high concordance between immunohistochemically detectable ERG expression and the presence of ERG rearrangement as seen in our series of Ewing sarcomas.

Given the prevalence of FLI1 rearrangement and FLI1 overexpression in Ewing sarcoma, an anti-FLI1 antibody can be helpful to distinguish between Ewing sarcoma and some histologically similar small-round cell tumors. However, lymphoblastic lymphomas, melanomas, merkel cell carcinoma, vascular tumors and desmoplastic small-round cell tumor can occasionally label for FLI1 depending on the antibody clone used.24, 26, 27, 28 Therefore, other immunohistochemical studies and/or molecular confirmation are recommended. Anti-Fli antibody is also well known to stain endothelial cells.23, 24, 29 In our series, anti-FLI1 antibody labeled the vast majority of our cases regardless of fusion variant, most commonly with a diffuse and moderate to strong labeling pattern. Although diffuse (5+) moderate-to-strong nuclear expression was seen in 18 out of 22 cases with EWSR1-FLI1 rearrangement, five of the seven Ewing sarcomas with EWSR1-ERG also had diffuse (5+) strong expression of FLI1. The overall sensitivity of the anti-FLI1 antibody for EWSR1-FLI1 was 95% and the specificity was 11%. One explanation for the poor specificity is the high probability of cross reactivity with the anti-FLI1 antibody. The anti-FLI1 antibody in our study was developed against bacterially expressed Ets domain of the FLI1 fusion protein. This region is highly conserved among the Ets transcription family members. Both FLI1 and ERG share 68% amino acid identity over their entire peptide sequence and 98% (83/85) amino acids identity in their Ets-binding domains.2 This antibody may be best considered as useful for the detection of Ets domains with high identity to FLI1, but is still useful within the proper context. In contrast, the anti-ERG antibody clone used in this study was generated against a short peptide, which maps to the last 30 amino acids of human ERG. Although the 87 amino acids adjacent to the Ets domain in Erg are 72% identical to FLI1, ERG only shares 30% of its last 30 residues with FLI1.30 (Figure 4) Neither antibody labeled tumors with EWSR1-NFATc2 rearrangement well, consistent with the poor sequence identity between these proteins including the lack of an Ets domain in NFATc2.

Simplified schematic diagram of EWSR1, FLI1, ERG and their fusion proteins in Ewing Sarcoma. The Ets domain is highly conserved between FLI1 and ERG, showing 98% amino acid sequence identity. Anti-FLI1 is generated against the Ets domain of the FLI1 fusion protein and likely cross-reacts with the Ets domain of ERG. In contrast, the anti-ERG antibody is generated against the last few amino acids at the C-terminus of ERG and has less sequence identity (about 30%) with FLI1.

ERG and FLI are members of the Ets (E-26) family, which contains a highly conserved 85 amino acid winged helix-loop-helix domain that mediates DNA binding to sequences containing a GGAA/T core motif. The combination with EWSR1, which belongs to the TET protein family and contains domains resembling transcription activation domains, results in a strong aberrant transcriptional activator that is overexpressed, as detected in all of our tumors with anti-ERG and anti-FLI1 antibodies. The expression of this fusion protein is thought to have a critical role in both the development and maintenance of the Ewing sarcoma phenotype. Not surprisingly, EWSR1-FLI1 is known to upregulate a variety of genes or likely multiple downstream effector genes, including those involved in proliferation, apoptosis evasion, cell cycle and angiogenesis as well as downregulate others, which likely contribute to tumorigenesis. Given the homology between the two proteins (particularly in the Ets domain), EWSR1-ERG in Ewing sarcoma likely interacts with similar, though not necessarily identical, groups of genes.2, 5 NFATc2 belongs to the NFAT family of transcription factors, regulating T cell and nerve development, and also recognizes sequences containing a GGAA/T core motif. Therefore, it is postulated that EWSR1-NFATc2 and EWSR1-Ets fusion proteins may also interact with a similar group of genes.2

Likewise, the behavior in Ewing sarcoma with EWSR1-FLI and EWSR1-ERG are similar. Ginsberg et al31 found no stastically significant difference in the clinical behavior between 106 patients with EWSR1-FLI1 Ewing sarcoma and 30 patients with EWSR1-ERG Ewing sarcoma. A more recent larger series from the Euro-EWING 99 clinical trial also failed to find any difference in clinical and histological features and outcomes (disease relapse and progression) in 520 patients with EWSR1-FLI1 and 45 patients with EWSR1-ERG. A small increase in progression/relapse was noted in patients with EWSR1-FLI1 non-type 1 or 2 fusions types but was not statistically significant.25 Regardless of fusion variant and type, Ewing sarcoma chimeric proteins result in an similar phenotype. In prostate carcinoma, the prognostic significance of ERG rearrangement remains debatable with multiple studies demonstrating variable association with outcome.9

In summary, to our knowledge, this is the first study examining ERG expression in Ewing sarcoma in comparison with FLI1 by immunohistochemical studies. Similar to studies on prostatic carcinomas, antibodies to the C-terminus of ERG are specific for Ewing sarcomas, which harbor a EWSR1-ERG rearrangement. In contrast, FLI1 was not specific to fusion type, likely because of cross-reactivity between the two proteins.

References

Gamberi G, Cocchi S, Benini S, et al. Molecular diagnosis in Ewing family tumors: the Rizzoli experience—222 consecutive cases in four years. J Mol Diagn 2011;13:313–324.

Sankar S, Lessnick SL . Promiscuous partnerships in Ewing's sarcoma. Cancer Genet 2011;204:351–365.

Zoubek A, Pfleiderer C, Salzer-Kuntschik M, et al. Variability of EWS chimaeric transcripts in Ewing tumours: a comparison of clinical and molecular data. Br J Cancer 1994;70:908–913.

Sorensen PH, Lessnick SL, Lopez-Terrada D, et al. A second Ewing's sarcoma translocation, t(21;22), fuses the EWS gene to another ETS-family transcription factor, ERG. Nat Genet 1994;6:146–151.

Arvand A, Denny CT . Biology of EWS/ETS fusions in Ewing's family tumors. Oncogene 2001;20:5747–5754.

Wang L, Bhargava R, Zheng T, et al. Undifferentiated small round cell sarcomas with rare EWS gene fusions: identification of a novel EWS-SP3 fusion and of additional cases with the EWS-ETV1 and EWS-FEV fusions. J Mol Diagn 2007;9:498–509.

Ng TL, O’Sullivan MJ, Pallen CJ, et al. Ewing sarcoma with novel translocation t(2;16) producing an in-frame fusion of FUS and FEV. J Mol Diagn 2007;9:459–463.

Szuhai K, Ijszenga M, de Jong D, et al. The NFATc2 gene is involved in a novel cloned translocation in a Ewing sarcoma variant that couples its function in immunology to oncology. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:2259–2268.

Clark JP, Cooper CS . ETS gene fusions in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol 2009;6:429–439.

Park K, Tomlins SA, Mudaliar KM, et al. Antibody-based detection of ERG rearrangement-positive prostate cancer. Neoplasia 2010;12:590–598.

Miettinen M, Wang ZF, Paetau A, et al. ERG transcription factor as an immunohistochemical marker for vascular endothelial tumors and prostatic carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2011;35:432–441.

van Leenders GJ, Boormans JL, Vissers CJ, et al. Antibody EPR3864 is specific for ERG genomic fusions in prostate cancer: implications for pathological practice. Mod Pathol 2011;24:1128–1138.

Paulo P, Barros-Silva JD, Ribeiro FR, et al. FLI1 is a novel ETS transcription factor involved in gene fusions in prostate cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2012;51:240–249.

Martens JH . Acute myeloid leukemia: a central role for the ETS factor ERG. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2011;43:1413–1416.

Yi H, Fujimura Y, Ouchida M, et al. Inhibition of apoptosis by normal and aberrant Fli-1 and erg proteins involved in human solid tumors and leukemias. Oncogene 1997;14:1259–1268.

Kruse EA, Loughran SJ, Baldwin TM, et al. Dual requirement for the ETS transcription factors Fli-1 and Erg in hematopoietic stem cells and the megakaryocyte lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009;106:13814–13819.

Loughran SJ, Kruse EA, Hacking DF, et al. The transcription factor Erg is essential for definitive hematopoiesis and the function of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Immunol 2008;9:810–819.

Birdsey GM, Dryden NH, Amsellem V, et al. Transcription factor Erg regulates angiogenesis and endothelial apoptosis through VE-cadherin. Blood 2008;111:3498–3506.

Birdsey GM, Dryden NH, Shah AV, et al. The transcription factor Erg regulates expression of histone deacetylase 6 and multiple pathways involved in endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis. Blood 2012;119:894–903.

Sperone A, Dryden NH, Birdsey GM, et al. The transcription factor Erg inhibits vascular inflammation by repressing NF-kappaB activation and proinflammatory gene expression in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2011;31:142–150.

Falzarano SM, Zhou M, Carver P, et al. ERG gene rearrangement status in prostate cancer detected by immunohistochemistry. Virchows Arch 2011;459:441–447.

Furusato B, Tan SH, Young D, et al. ERG oncoprotein expression in prostate cancer: clonal progression of ERG-positive tumor cells and potential for ERG-based stratification. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2010;13:228–237.

Folpe AL, Chand EM, Goldblum JR, et al. Expression of Fli-1, a nuclear transcription factor, distinguishes vascular neoplasms from potential mimics. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:1061–1066.

Rossi S, Orvieto E, Furlanetto A, et al. Utility of the immunohistochemical detection of FLI-1 expression in round cell and vascular neoplasm using a monoclonal antibody. Mod Pathol 2004;17:547–552.

Le Deley MC, Delattre O, Schaefer KL, et al. Impact of EWS-ETS fusion type on disease progression in Ewing's sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor: prospective results from the cooperative Euro-E.W.I.N.G. 99 trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1982–1988.

Folpe AL, Hill CE, Parham DM, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of FLI-1 protein expression: a study of 132 round cell tumors with emphasis on CD99-positive mimics of Ewing's sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:1657–1662.

Llombart-Bosch A, Navarro S . Immunohistochemical detection of EWS and FLI-1 proteinss in Ewing sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumors: comparative analysis with CD99 (MIC-2) expression. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2001;9:255–260.

Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Herrmann F, Penetrante R, et al. Diagnostic utility of FLI-1 monoclonal antibody and dual-colour, break-apart probe fluorescence in situ (FISH) analysis in Ewing's sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumour (EWS/PNET). A comparative study with CD99 and FLI-1 polyclonal antibodies. Histopathology 2006;49:569–575.

Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Herrmann FR, Bshara W, et al. Friend leukaemia integration-1 expression in malignant and benign tumours: a multiple tumour tissue microarray analysis using polyclonal antibody. J Clin Pathol 2007;60:694–700.

Epitomics ITS. (e-mail communication from the Antibody manufacturer) 2012.

Ginsberg JP, de Alava E, Ladanyi M, et al. EWS-FLI1 and EWS-ERG gene fusions are associated with similar clinical phenotypes in Ewing's sarcoma. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:1809–1814.

Acknowledgements

We like to acknowledge Kim Vu for her expert assistance in the figures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, WL., Patel, N., Caragea, M. et al. Expression of ERG, an Ets family transcription factor, identifies ERG-rearranged Ewing sarcoma. Mod Pathol 25, 1378–1383 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2012.97

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2012.97

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Co-expression of ERG and CD31 in a subset of CIC-rearranged sarcoma: a potential diagnostic pitfall

Modern Pathology (2022)

-

Neues in der aktuellen WHO-Klassifikation (2020) für Weichgewebssarkome

Der Pathologe (2021)

-

NFATc2-rearranged sarcomas: clinicopathologic, molecular, and cytogenetic study of 7 cases with evidence of AGGRECAN as a novel diagnostic marker

Modern Pathology (2020)

-

Survey of ERG expression in normal bone marrow and myeloid neoplasms

Journal of Hematopathology (2020)

-

Ewing sarcoma and Ewing-like tumors

Virchows Archiv (2020)