Abstract

The patient was a 54-year-old woman who developed a right adrenal tumour, Cushingoid features, elevated levels of cortisol that were not suppressed by 1 nor 8 mg of dexamethasone, and suppression of adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) during treatment for severe hypertension. Computed tomography (CT) revealed a right adrenal tumour and an atrophic left adrenal gland. In addition, elevated plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC) and suppressed plasma renin activity (PRA) with an aldosterone-to-renin ratio of 128 (ng per 100 ml per ng ml–1 h−1) suggested aldosterone excess. Urinary excretion of aldosterone was relatively high, and the captopril and rapid ACTH tests resulted in no response of PRA and exaggerated increase in PAC, respectively. ACTH-loaded adrenal venous sampling showed bilateral excess of aldosterone with right predominance of cortisol. Right laparoscopic partial adrenalectomy (ADX) and immunohistochemical analysis showed both a cortisol-producing adenoma and an aldosterone-producing microadenoma (microAPA) within the attached adrenal, which had not been detected by CT preoperatively. After the right partial ADX, her blood pressure, aldosterone level and suppressed PRA remained unchanged. Subsequently, laparoscopic total left ADX was performed. Two microAPAs with paradoxical hyperplasia were revealed within the apparently atrophic left adrenal gland. Soon after the second surgery, her blood pressure normalized without requiring any anti-hypertensive medication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aldosterone, in concert with a high salt intake, has a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of hypertension and causes potentially serious damage to the cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and renal systems, resulting in atherosclerotic and/or fibrotic remodeling through activation of mineralocorticoid receptors1 or other mechanisms not yet elucidated. Primary aldosteronism has been attracting more and more attention from clinical and basic scientists, because its prevalence in referral centres has been reported to be more than 10% among hypertensive patients,2 making it a common disease rather than an unusual endocrine disorder. Cortisol has been widely studied as a possible culprit of metabolic syndrome. Excess secretion of both aldosterone and cortisol, therefore, might result in severe hypertension and comorbidities.

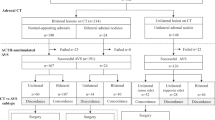

We describe the case of a patient in whom hypersecretion of aldosterone and cortisol resulted in difficult-to-control hypertension. The patient was diagnosed as having adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-independent Cushing syndrome with concomitant hypersecretion of aldosterone. Lateralization of aldosterone hypersecretion was determined by bolus cosyntropin-stimulated adrenal venous sampling (AVS). On the basis of the results obtained by AVS, two-stage surgery, that is, right partial adrenalectomy (ADX) and subsequent total left ADX, was performed to stop excessive secretion of both hormones. After the surgery, severe hypertension resolved, and eventually this case presented an unreported condition of bilateral aldosterone-producing microadenomas (microAPAs) associated with a cortisol-producing adrenal macroadenoma.

Case report

A 54-year-old woman was referred to our hospital for evaluation of hypertension and a right adrenal tumour. She had been diagnosed as having hypertension and had started taking anti-hypertensive medication at the age of 42. A few months before her referral to our hospital, abdominal ultrasonography for a routine check-up revealed that she had a right adrenal tumour, and she was admitted for further evaluation.

On admission she showed central obesity, BMI of 27 kg m–2 and a moon face. Her blood pressure was 152/106 mm Hg with a pulse rate of 65 beats per minute although she was on nifedipine 40 mg day–1, bunazosin 6 mg day–1 and carvedilol 10 mg day–1. On physical examination, she showed pretibial oedema and multiple ecchymoses on her lower extremities. Before the evaluation of the adrenal tumour and hypertension, carvedilol was discontinued, and both benidipine and doxazosin were added to control her blood pressure. We intentionally limited the use of anti-hypertensive agents to calcium-channel blockers and alpha1-blockers to minimize effects on renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system by other medications during a diagnostic process.2 Complete blood cell count and electrolyte analysis showed a mildly elevated neutrophil count of 76%, a decreased eosinophil count of 1% without leukocytosis and normokalemia of 4.1 mmol l–1 (Table 1). Repeated 24-h urinary collections showed an average creatinine clearance of 78 ml min–1 with microalbuminuria of 61 mg day–1. The endocrinological examination (Table 1) revealed that the circadian rhythm of the hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal axis was disturbed with both persistently suppressed ACTH levels (assay sensitivity: 5 pg ml–1) and elevated cortisol levels ranging from 17.1 to 24.0 μg per 100 ml. The levels of urinary free cortisol were also elevated. Overnight dexamethasone suppression tests with 1 and 8 mg resulted in cortisol levels of 17.4 and 14.7 μg per 100 ml, respectively. These results were consistent with autonomous secretion of cortisol, and she was diagnosed as having Cushing syndrome. Adrenal computed tomography (CT) with contrast medium showed a right adrenal tumour of 30 mm in diameter (Figure 1a), while the left adrenal gland was found to be atrophic (Figure 1b). Furthermore, elevated plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC) of 12.8 ng per 100 ml and suppressed plasma renin activity (PRA) of 0.1 ng ml–1 h−1, which gave an aldosterone-to-renin ratio (ARR) of 128, prompted us to confirm concomitant aldosterone excess.

The circadian study showed elevated PAC (over 12 ng per 100 ml) except for the one obtained at 2300 hours along with persistently suppressed PRA (<1 ng ml–1 h−1) throughout the day, and the captopril test resulted in no significant increase in PRA with the ARR being 20.8 at 60 min (Table 1). In addition, a rapid ACTH test with 0.25 mg cosyntropin elicited a marked increase of aldosterone to 67.1 ng per 100 ml. AVS was performed, as reported previously,3 to determine the laterality of excessive secretion of aldosterone and cortisol. Cortisol levels from the right adrenal vein obtained before and after cosyntropin stimulation were 146 and 1269 μg per 100 ml, respectively, and 6.3- and 8.8-fold higher than those from the left adrenal vein, respectively, confirming that the source of cortisol excess was the right adrenal side (Table 2). Aldosterone levels obtained from the right and left adrenal veins were 198 and 211 ng per 100 ml respectively at baseline, and 2545 and 7134 ng per 100 ml respectively, after an iv bolus injection of 0.25 mg cosyntropin (Table 2). On the basis of these results, we judged that the patient presented hypersecretion of aldosterone from bilateral adrenals with left predominance.3, 4, 5 Bilateral excess of aldosterone shown in AVS raised some possibilities; (1) bilateral adrenal hyperplasia, that is, idiopathic hyperaldosteronism; (2) the CT-detectable right adrenal produced both cortisol and aldosterone in addition to the CT-undetectable microAPA within the left adrenal gland; and (3) microAPAs were present in bilateral adrenal glands. As it was not possible to differentiate between tumour and hyperplasia except by histopathological examination, we performed laparoscopic partial ADX of the right adrenal tumour to spare as much of the apparently atrophic but non-tumourous attached adrenal gland as possible, leaving the possibility that the left adrenal gland might be resected if excessive secretion of aldosterone and difficult-to-control hypertension persisted.

Histopathological examination revealed that the right adrenal tumour was 25 mm in diameter, and hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining showed that it was composed of compact and clear cells with predominance of the compact ones, fulfilling two out of nine Weiss criteria,6, 7 that is, eosinophilic cytoplasm and nuclear atypia, with focal lipoid degeneration (Figure 2a). Immunohistochemistry of the right tumour showed immunoreactivity to 3 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD) and 17α-hydroxylase (P450c17) in the cytoplasm (Figures 2d and g, respectively). In grossly atrophic, non-neoplastic tissue of the right adrenal attached to the right tumour, there was a micronodule of 2.1 mm in diameter (Figure 2b, HE staining). Homogenously increased immunoreactivity to 3β-HSD (Figure 2e) with diffusely attenuated immunoreactivity to P450c17 (Figure 2h) coincided with the micronodule, indicating this was a microAPA.8 The rest of the attached non-neoplastic tissue of the right adrenal showed atrophy of the zona fasciculata and reticularis (Figure 2c, HE staining), and decreased immunoreactivity to 3β-HSD (Figure 2f) and P450c17 (Figure 2i), consistent with ACTH-independent Cushing syndrome. The zona glomerulosa, in particular, of the right attached non-neoplastic adrenal showed hyperplastic changes with focally attenuated immunoreactivity to 3β-HSD (Figure 2f), suggesting the ‘paradoxical hyperplasia’ observed in patients with aldosterone-producing adenomas (APA).8

Histopathology of the right adrenal tumour and the attached non-neoplastic adrenal tissue. (a, d, g) The right adrenal tumour, (b, e, h) the aldosterone-producing microAPA (indicated by arrowhead) and (c, f, i) the attached non-neoplastic adrenal tissue, analyzed by HE staining and immunohistochemistry of 3β-HSD and P450c17, respectively.

Immediately after the right partial ADX, the patient started to receive glucocorticoid replacement with dexamethasone, and her cortisol level decreased to undetectable using an assay with a sensitivity of 0.8 μg per 100 ml. Her signs of Cushing syndrome including moon face and central obesity as well as pretibial oedema disappeared. The aldosterone level remained, however, almost unchanged. Subsequently, her blood pressure began to rise after the partial ADX, resulting in the addition of azelnidipine 16 mg day–1 to the preoperative regimen. Eight months after the right partial ADX, a second endocrinological examination was performed (Table 1, right column). Circadian examination of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system showed PAC ranging from 8.0 to 15.0 ng per 100 ml with persistently suppressed PRA of <1 ng ml–1 h−1 throughout the day, while the endogenous ACTH was still undetected after the cure of Cushing syndrome. Repeated measurement of urinary steroids confirmed elevated aldosterone excretion with the highest level being 9.7 μg day–1 and the median 8.9 μg day–1. Both post-captopril ARR of 19.6 at 60 min and the exaggerated aldosterone response (up to 54.4 ng per 100 ml) in the rapid ACTH test suggested persistence of aldosterone excess. On the basis of the histological proof of a microAPA in the resected right adrenal tissue and the results of AVS, we strongly suspected that the origin of aldosterone excess might lie in the left adrenal gland. We then performed laparoscopic total left ADX, based on the endocrinological assessment and the patient's strong wish to control her hypertension requiring multiple anti-hypertensive agents of nifedipine 40 mg day–1, benidipine 8 mg day–1, azelnidipine 16 mg day–1, doxazosin 4 mg day–1 and bunazosin 6 mg day–1.

Immediately after the second ADX, her blood pressure returned to normal without requiring any anti-hypertensives, and PAC went down to 2.8 ng per 100 ml with a PRA of 0.3 ng ml–1 h−1; besides, urinary excretion of aldosterone decreased to undetectable by postoperative day 7. Within the left adrenal gland, HE staining showed two micronodules, one of 1.6 mm (Figure 3a) and the other of 1.9 mm (Figure 3b) in diameter, both of which showed increased homogenous immunoreactivity to 3β-HSD (Figures 3d and e, respectively), but not to P450c17 (Figures 3g and 3h, respectively). Moreover, except for these two micronodules, the left attached non-neoplastic adrenal showed hyperplasia of the zona glomerulosa (Figure 3c), which was diffusely negative for immunoreactivity to 3β-HSD (Figure 3f), indicating ‘paradoxical hyperplasia’.8

Histopathology of the left adrenal gland. (a, d, g) One aldosterone-producing microAPA (indicated by arrowhead), (b, e, h) another aldosterone-producing microAPA (indicated by arrowhead) and (c, f, i) the attached non-neoplastic adrenal tissue, analyzed by HE staining and immunohistochemistry of 3β-HSD and P450c17, respectively. (f) The hyperplastic zona glomerulosa showing negative immunoreactivity to 3β-HSD (arrowheads) showed paradoxical hyperplasia in the attached non-neoplastic adrenal tissue.

Finally, the patient was diagnosed as having a cortisol-producing adrenocortical adenoma and a microAPA in the right adrenal gland and two microAPAs in the left adrenal gland. She remained normotensive without any anti-hypertensive medication and fit with appropriate glucocorticoid replacement, and a rapid cosyntropin stimulation test performed 18 months after the second ADX showed no response of cortisol from baseline of 1.1 μg per 100 ml and diminished response of aldosterone from 4.2 to 12.8 ng per 100 ml, as compared with the peak level of 54.4 ng per 100 ml before the second ADX.

Discussion

We have described the successful treatment of a patient with severe endocrine hypertension attributed to hypersecretion of cortisol and aldosterone because of unilateral, CT-detectable macroadenoma and bilateral, CT-undetectable microAPAs. Although several cases of simultaneous hypersecretion of cortisol and aldosterone have been reported, most of them were classified into two groups: one because of a single, sometimes multiple, adrenocortical macroadenoma(s) that produced both cortisol and aldosterone,9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and the other because of a combination of cortisol-producing macroadenoma(s) and aldosterone-producing macroadenoma(s).15, 16, 17, 18 Furthermore, the preoperative diagnosis of most of these cases were made on radiological findings obtained by conventional CT as well as on endocrinological findings.9, 11, 12, 15, 16 In this case, we preoperatively suspected the hypersecretion of aldosterone from bilateral adrenals from the results of AVS, and confirmed bilateral microAPAs as the cause of aldosterone excess by immunohistochemical analysis of steroidogenic enzymes.

According to the Endocrine Society Guidelines for management of primary aldosteronism,2 a stepwise approach is recommended to evaluate hypersecretion of aldosterone: screening, confirmation tests and subtype classification. We considered that the diagnostic workup of aldosterone excess required careful interpretation of endocrinological findings, especially in the situation that the secretion of endogenous ACTH was suppressed as in the present case, because previous studies had found that aldosterone secretion in patients with an APA was regulated mainly by ACTH and potassium levels, provided that the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system was suppressed.19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 The diurnal rhythm of PAC in patients with an APA was reported to depend on that of endogenous ACTH25, 26, 27, 28 and became ambiguous when the endogenous secretion of ACTH was disturbed by supraphysiological doses of dexamethasone.21, 26, 28 Besides, the absolute levels of PAC decreased when the ACTH levels were suppressed by exogenous glucocorticoids.21, 26, 28 Our patient was complicated by ACTH-independent Cushing syndrome with totally suppressed levels of endogenous ACTH, suggesting that her levels of PAC might have been higher than the physiological levels. Although her plasma aldosterone levels showed no obvious diurnal rhythm fluctuation, they were mostly higher than 12 ng per 100 ml, and the ARR was consistently higher than 40, fulfilling the screening criteria.2 After the first ADX, the second circadian study of hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal axis and renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system revealed a mean aldosterone level of 11.45 ng per 100 ml without the apparent diurnal variation observed when PRA is consistently <1 ng ml–1 h−1. This decrement in PAC might be partly attributable to the resection of the right microAPA, and we considered that the high ARR (>20) after the first surgery suggested persistent aldosterone excess.

The second step in the evaluation of hypersecretion of aldosterone lies in confirmatory tests. In our patient, the volume-overloaded state was evident at the initial visit and we chose a captopril test. The results of this test before and after the first ADX were ARR of 20.8 and 19.6, respectively. Although the second ARR was slightly below the cut-off level of 20 probably because of a decrease in the aldosterone level, implying that the aldosterone excess was partly dependent on angiotensin II, we considered that both results were high enough to interpret that somewhat autonomous secretion of aldosterone might exist considering the suppression of ACTH secretion.

As another confirmatory test, we performed the rapid ACTH test to consolidate our assumption that aldosterone excess might be involved. Some research groups have advocated that an APA produces an exaggerated increase in aldosterone in response to exogenous ACTH stimulation19, 20, 22, 23, 24 and that this finding is helpful to differentiate patients with PA from those with low-renin essential hypertension. Indeed, expression of the melanocortin receptor type 2 in APA is significantly elevated compared with normal adrenal tissue29, 30, 31, 32 and other adrenocortical tumours, including cortisol-producing ones.33, 34, 35 Therefore, the exaggerated response of aldosterone through melanocortin receptor type 2 detected with the rapid ACTH test is useful to distinguish APAs from other cortical tumours.32, 35 Accordingly, we adopted the rapid ACTH test as another confirmatory test. Stimulation with 0.25 mg cosyntropin elicited peak aldosterone levels as high as 67.1 and 54.4 ng per 100 ml before and after the first ADX, respectively, strongly suggesting the concomitant excess of aldosterone.

After the confirmation of autonomous excessive secretion of aldosterone, AVS was performed to decide the laterality of aldosterone hypersecretion.2 As for the interpretation of the AVS results, while many research groups have advocated their methods and cut-off values,2 this case may provide valuable opportunity for interpretation of AVS in patients with concomitant ACTH-independent Cushing syndrome. In patients with autonomous secretion of cortisol, it would be inappropriate to decide laterality of aldosterone hypersecretion based on cortisol-corrected aldosterone levels. The cut-off levels of aldosterone hypersecretion were reported to be 1340 and 1400 ng per 100 ml by two research groups, including ours.3, 4, 5 In this case, levels of aldosterone after cosyntropin stimulation exceeded 1400 ng per 100 ml bilaterally, indicating that bilateral aldosterone excess might be present, which was subsequently confirmed by the presence of bilateral microAPAs. In addition, the AVS showed the higher aldosterone level in the left adrenal vein than that in the right after cosyntropin stimulation, in contrast to the comparable levels of both adrenals at baseline. This might be partly attributed to possible difference in capacity of the aldosterone-producing microAPAs to secrete aldosterone in response to cosyntropin.

The ‘re-advent’ of AVS for clinical practice has been associated with an increasing number of reports on CT-undetectable microAPAs in patients with primary aldosteronism.36, 37, 38, 39 The diagnosis of microAPA, in our view, should be histopathologically confirmed in two ways; a micronodule should be detected by HE staining, and subsequently immunohistochemically examined for expression of steroidogenic enzymes.8, 40 The requisite for diagnosis of a microAPA should include increased expression of 3β-HSD and attenuated or negative expression of P450c17 within the lesion, which can be further supported by the presence of ‘paradoxical hyperplasia’, that is, suppressed or negative expression of 3β-HSD in the zona glomerulosa of the attached adrenal tissue.8 All the micronodules diagnosed as microAPAs in this case satisfied these two conditions.

Furthermore, the cortisol might have a role in the pathogenesis of severe hypertension in this case. The autonomous and excessive secretion of cortisol caused sodium and volume retention, resulting in pitting oedema, which is not typically observed in patients with primary aldosteronism. After the first ADX, Cushing syndrome was remitted and signs of volume-overloaded state disappeared, while the hypertension persisted with the aldosterone levels almost unchanged, suggesting that the cortisol might be a deteriorating factor to cause excessive sodium reabsorption under the circumstances that the excessive aldosterone might have a pivotal role to keep blood pressure still elevated.

References

Rossi GP, Sechi LA, Giacchetti G, Ronconi V, Strazzullo P, Funder JW . Primary aldosteronism: cardiovascular, renal and metabolic implications. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2008; 19: 88–90.

Funder JW, Carey RM, Fardella C, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Mantero F, Stowasser M et al. Case detection, diagnosis, and treatment of patients with primary aldosteronism: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: 3266–3281.

Satoh F, Abe T, Tanemoto M, Nakamura M, Abe M, Uruno A et al. Localization of aldosterone-producing adrenocortical adenomas: significance of adrenal venous sampling. Hypertens Res 2007; 30: 1083–1095.

Omura M, Sasano H, Fujiwara T, Yamaguchi K, Nishikawa T . Unique cases of unilateral hyperaldosteronemia due to multiple adrenocortical micronodules, which can only be detected by selective adrenal venous sampling. Metabolism 2002; 51: 350–355.

Omura M, Saito J, Yamaguchi K, Kakuta Y, Nishikawa T . Prospective study on the prevalence of secondary hypertension among hypertensive patients visiting a general outpatient clinic in Japan. Hypertens Res 2004; 27: 193–202.

Weiss LM . Comparative histologic study of 43 metastasizing and nonmetastasizing adrenocortical tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 1984; 8: 163–169.

Weiss LM, Medeiros LJ, Vickery Jr AL . Pathologic features of prognostic significance in adrenocortical carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1989; 13: 202–206.

Sasano H . The adrenal cortex. In: Stefaneanu L, Sasano H, Kovacs K (eds). Molecular and Cellular Endocrine Pathology. Arnold: London, 2000, pp 221–252.

Honda T, Nakamura T, Saito Y, Ohyama Y, Sumino H, Kurabayashi M . Combined primary aldosteronism and preclinical Cushing′s syndrome: an unusual case presentation of adrenal adenoma. Hypertens Res 2001; 24: 723–726.

Makino S, Oda S, Saka T, Yasukawa M, Komatsu F, Sasano H . A case of aldosterone-producing adrenocortical adenoma associated with preclinical Cushing′s syndrome and hypersecretion of parathyroid hormone. Endocr J 2001; 48: 103–111.

Sugawara A, Takeuchi K, Suzuki T, Itoi K, Sasano H, Ito S . A case of aldosterone-producing adrenocortical adenoma associated with a probable post-operative adrenal crisis: histopathological analyses of the adrenal gland. Hypertens Res 2003; 26: 663–668.

Suzuki J, Otsuka F, Inagaki K, Otani H, Miyoshi T, Terasaka T et al. Primary aldosteronism caused by a unilateral adrenal adenoma accompanied by autonomous cortisol secretion. Hypertens Res 2007; 30: 367–373.

Tsunoda K, Abe K, Yamada M, Kato T, Yaoita H, Taguma Y et al. A case of primary aldosteronism associated with renal artery stenosis and preclinical Cushing′s syndrome. Hypertens Res 2008; 31: 1669–1675.

Rossi E, Foroni M, Regolisti G, Perazzoli F, Negro A, Santi R et al. Combined Conn′s syndrome and subclinical hypercortisolism from an adrenal adenoma associated with homolateral renal carcinoma. Am J Hypertens 2008; 21: 1269–1272.

Okura T, Miyoshi K, Watanabe S, Kurata M, Irita J, Manabe S et al. Coexistence of three distinct adrenal tumors in the same adrenal gland in a patient with primary aldosteronism and preclinical Cushing′s syndrome. Clin Exp Nephrol 2006; 10: 127–130.

Saito T, Ikoma A, Saito T, Tamemoto H, Suminaga Y, Yamada S et al. Possibly simultaneous primary aldosteronism and preclinical Cushing′s syndrome in a patient with double adenomas of right adrenal gland. Endocr J 2007; 54: 287–293.

Oki K, Yamane K, Sakashita Y, Kamei N, Watanabe H, Toyota N et al. Primary aldosteronism and hypercortisolism due to bilateral functioning adrenocortical adenomas. Clin Exp Nephrol 2008; 12: 382–387.

Onoda N, Ishikawa T, Nishio K, Tahara H, Inaba M, Wakasa K et al. Cushing′s syndrome by left adrenocortical adenoma synchronously associated with primary aldosteronism by right adrenocortical adenoma: report of a case. Endocr J 2009; 56: 495–502.

Newton MA, Laragh JH . Effect of corticotropin on aldosterone excretion and plasma renin in normal subjects, in essential hypertension and in primary aldosteronism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1968; 28: 1006–1013.

Slaton Jr PE, Schambelan M, Biglieri EG . Stimulation and suppression of aldosterone secretion in patients with an aldosterone-producing adenoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1969; 29: 239–250.

Cain JP, Tuck ML, Williams GH, Dluhy RG, Rosenoff SH . The regulation of aldosterone secretion in primary aldosteronism. Am J Med 1972; 53: 627–637.

Ganguly A, Melada GA, Luetscher JA, Dowdy AJ . Control of plasma aldosterone in primary aldosteronism: distinction between adenoma and hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1973; 37: 765–775.

Kem DC, Weinberger MH, Higgins JR, Kramer NJ, Gomez-Sanchez C, Holland OB . Plasma aldosterone response to ACTH in primary aldosteronism and in patients with low renin hypertension. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1978; 46: 552–560.

Stowasser M, Klemm SA, Tunny TJ, Gordon RD . Plasma aldosterone response to ACTH in subtypes of primary aldosteronism. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 1995; 22: 460–462.

Kem DC, Weinberger MH, Gomez-Sanchez C, Kramer NJ, Lerman R, Furuyama S et al. Circadian rhythm of plasma aldosterone concentration in patients with primary aldosteronism. J Clin Invest 1973; 52: 2272–2277.

Vetter H, Berger M, Armbruster H, Siegenthaler W, Werning C, Vetter W . Episodic secretion of aldosterone in primary aldosteronism: relationship to cortisol. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1974; 3: 41–48.

Schambelan M, Brust NL, Chang BC, Slater KL, Biglieri EG . Circadian rhythm and effect of posture on plasma aldosterone concentration in primary aldosteronism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1976; 43: 115–131.

Kem DC, Weinberger MH, Gomez-Sanchez C, Higgins JR, Kramer NJ . The role of ACTH in the episodic release of aldosterone in patients with idiopathic adrenal hyperplasia, hypertension, and hyperaldosteronism. J Lab Clin Med 1976; 88: 261–270.

Reincke M, Beuschlein F, Latronico AC, Arlt W, Chrousos GP, Allolio B . Expression of adrenocorticotrophic hormone receptor mRNA in human adrenocortical neoplasms: correlation with P450scc expression. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1997; 46: 619–626.

Reincke M, Beuschlein F, Menig G, Hofmockel G, Arlt W, Lehmann R et al. Localization and expression of adrenocorticotropic hormone receptor mRNA in normal and neoplastic human adrenal cortex. J Endocrinol 1998; 156: 415–423.

Ye P, Mariniello B, Mantero F, Shibata H, Rainey WE . G-protein-coupled receptors in aldosterone-producing adenomas: a potential cause of hyperaldosteronism. J Endocrinol 2007; 195: 39–48.

Zwermann O, Suttmann Y, Bidlingmaier M, Beuschlein F, Reincke M . Screening for membrane hormone receptor expression in primary aldosteronism. Eur J Endocrinol 2009; 160: 443–451.

Allolio B, Reincke M . Adrenocorticotropin receptor and adrenal disorders. Horm Res 1997; 47: 273–278.

Beuschlein F, Fassnacht M, Klink A, Allolio B, Reincke M . ACTH-receptor expression, regulation and role in adrenocortial tumor formation. Eur J Endocrinol 2001; 144: 199–206.

Mancini T, Kola B, Mantero F, Arnaldi G . Functional and nonfunctional adrenocortical tumors demonstrate a high responsiveness to low-dose adrenocorticotropin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88: 1994–1998.

Omura M, Sasano H, Saito J, Yamaguchi K, Kakuta Y, Nishikawa T . Clinical characteristics of aldosterone-producing microadenoma, macroadenoma, and idiopathic hyperaldosteronism in 93 patients with primary aldosteronism. Hypertens Res 2006; 29: 883–889.

Nishizawa K, Nakamura E, Kobayashi T, Kamoto T, Terai A, Terachi T et al. Successful treatment of primary aldosteronism due to computed tomography-negative microadenoma. Int J Urol 2003; 10: 544–546.

Tamura Y, Adachi J, Chiba Y, Mori S, Takeda K, Kasuya Y et al. Primary aldosteronism due to unilateral adrenal microadenoma in an elderly patient: efficacy of selective adrenal venous sampling. Intern Med 2008; 47: 37–42.

Myint KS, Watts M, Appleton DS, Lomas DJ, Jamieson N, Taylor KP et al. Primary hyperaldosteronism due to adrenal microadenoma: a curable cause of refractory hypertension. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 2008; 9: 103–106.

Sasano H . Localization of steroidogenic enzymes in adrenal cortex and its disorders. Endocr J 1994; 41: 471–482.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all the health-care professionals who dedicated their expertise to the care of the patient described in the present report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Morimoto, R., Kudo, M., Murakami, O. et al. Difficult-to-control hypertension due to bilateral aldosterone-producing adrenocortical microadenomas associated with a cortisol-producing adrenal macroadenoma. J Hum Hypertens 25, 114–121 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/jhh.2010.35

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/jhh.2010.35

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Hypercortisolism and primary aldosteronism caused by bilateral adrenocortical adenomas: a case report

BMC Endocrine Disorders (2019)