Abstract

Purpose:

Internet-based technologies are increasingly being used for research studies. However, it is not known whether Internet-based approaches will effectively engage participants from diverse racial and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Methods:

A total of 967 participants were recruited and offered genetic ancestry results. We evaluated viewing Internet-based genetic ancestry results among participants who expressed high interest in obtaining the results.

Results:

Of the participants, 64% stated that they were very or extremely interested in their genetic ancestry results. Among interested participants, individuals with a high school diploma (n = 473) viewed their results 19% of the time relative to 4% of the 145 participants without a diploma (P < 0.0001). Similarly, 22% of participants with household income above the federal poverty level (n = 286) viewed their results relative to 10% of the 314 participants living below the federal poverty level (P < 0.0001). Among interested participants both with a high school degree and living above the poverty level, self-identified Caucasians were more likely to view results than self-identified African Americans (P < 0.0001), and females were more likely to view results than males (P = 0.0007).

Conclusion:

In an underserved population, engagement in Internet-based research was low despite high reported interest. This suggests that explicit strategies should be developed to increase diversity in Internet-based research.

Genet Med 19 2, 240–243.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

As comprehensive medical databases are constructed to include hundreds of thousands of participants, Internet-based technologies are increasingly being used for participant recruitment and retention in medical research studies. In an effort to recruit 1 million US participants from diverse racial and socioeconomic backgrounds, the Precision Medicine Initiative (PMI) Working Group recommended the design of a centralized, bidirectional “participant portal” that can be used by participants to provide data and to access results of studies.1,2 Furthermore, they suggested using e-mail and text messages to remind participants of their value to the PMI cohort, strategies consistent with participant-centric initiatives.2,3,4 However, it is not known whether these Internet-based approaches will engage the underrepresented groups that the PMI Working Group seeks to enroll.

Interest in medical research is high across demographic groups. The PMI Working Group reported high interest in participation among a sample of 2,601 potential participants that included a large number of underrepresented cohorts.2 Similarly, a University of Maryland survey of 169 outpatients found that willingness to join a biobank was not associated with gender, race, or socioeconomic factors.5 By contrast, clinical studies have found that study engagement and retention are low among underserved populations, including African Americans and individuals without a high school education.6,7

Because 84% of American adults use the Internet8 and 68% own a smartphone,9 it is thought that leveraging digital technologies will be an effective method for engagement of all participants, including those who are typically underrepresented in research studies. In this study we measured participant engagement by tracking online viewing of ancestry results and evaluated how engagement varies across demographic and socioeconomic factors.

Materials and Methods

Participants were enrolled in a genetic study of smoking, which was approved by the institutional review board at Washington University in St. Louis. All participants gave informed consent. Participants were recruited in 2014 from the St. Louis metropolitan area; 89% were recruited via flyers or word of mouth, 6% were recruited from the research participant registry at Washington University (https://vfh.wustl.edu), 3% were recruited from Craigslist, and 2% were recruited from Facebook. All participants were current smokers, as demonstrated by a minimum exhaled carbon monoxide level of 5 parts per million, and they had to be able to consent to study participation in English. After the informed-consent process, participants were given a brief (30-min) semistructured, computer-assisted interview to assess baseline demographics, substance-use history, and health-care literacy as measured by the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine–Revised.10

Genetic analysis was performed by 23andMe (https://www.23andMe.com). As an incentive for participation in the smoking study, participants were offered access to their genetic ancestry results through the 23andMe website. As part of the informed-consent process, participants were told that they would receive their genetic ancestry results and were shown an example of the results. Both the Internet and paper flyers advertised that the participants would receive genetic ancestry results. The interview included the question “How interested are you in seeing your genetic ancestry results?” Response options were “not at all interested,” “slightly interested,” “moderately interested,” “very interested,” and “extremely interested.” After the assessment was complete, participants donated a saliva sample. Participants were assisted by the research staff in creating a personal account on the 23andMe website, which required an e-mail address; 83% of participants had an established e-mail address. Those who did not were assisted in creating an e-mail account. Participants were given a sheet on which to record their user names and passwords for future reference.

Four to 6 weeks following participation in the study, participants were informed that their ancestry results were ready and given instructions on how to access them. To view the results, participants had to log into their established 23andMe account. 23andMe has an easily navigable, user-friendly website and mobile interface.

The investigative team tracked how many participants viewed their genetic ancestry results, as measured by whether a participant logged into 23andMe after their genetic results were available. Neither the length of time spent on the 23andMe website nor the number of logins was recorded. To ensure that participants were informed about the availability of their results, those who did not log into their 23andMe account after their ancestry results were available were contacted a minimum of four times using a variety of methods. If participants had still had not picked up their results after being contacted via e-mail and telephone, they were sent a letter by first-class mail. Participants were given at least 6 months to pick up their ancestry results before being classified as having not reviewed their genetic results.

Data analysis included chi-squared testing and logistic regression and was completed using SAS version 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

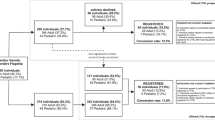

23andMe results were obtained for 967 participants. A total of 114 participants (12%) viewed their genetic ancestry results ( Table 1 ). Demographics are given in Table 1 . Consistent with 2014 St. Louis Census data,11 participants without a high school degree (or general equivalency diploma) were less likely to be European-American (P = 0.0002) and more likely to live in a household with a total income below the federal poverty level (P < 0.0001).

A majority of participants expressed strong interest in receiving genetic ancestry results: 64% said they were “very” or “extremely” interested ( Table 1 ). Participants with a high school education were more likely to have a higher level of interest in receiving genetic ancestry results than participants without a high school education (P = 0.01). Gender, race, and income did not statistically influence whether the participants were interested in the results.

Few participants (4%) who said they were “not at all interested,” “slightly interested,” or “moderately interested” in their genetic ancestry results actually viewed their results, which we deemed to be in line with their stated interest. We therefore focused on further examining the group of participants who said they were “very” or “extremely” interested in receiving their genetic ancestry results. Surprisingly, even of these participants who expressed high interest, only 16% actually viewed their results.

We then investigated sociodemographic factors associated with viewing ancestry results among this highly interested group ( Figure 1 ). Regardless of gender or race, interested participants rarely viewed results if they did not complete high school (P < 0.0001) or had a household income below the federal poverty level (P < 0.0001; Figure 1a ). Among participants who both completed high school and had a household income above the federal poverty level, men were less likely than women to view results (P = 0.0001), and African Americans were less likely than European Americans to view results (P < 0.0001; Figure 1b ). There was no statistical interaction on viewing results between gender and race.

Education, poverty, gender and race impact participant engagement. (a) Viewing genetic ancestry results by participants who reported being “extremely” or “very” interested in viewing results varies by education and income. (b) Viewing genetic ancestry differs across gender and race among interested participants who completed high school and have a household income above the federal poverty level. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals; P values are from logistic regression adjusted for age, gender, and race.

Discussion

Participant engagement is a core feature of the PMI. This study examined participant engagement in Internet-based research by tracking whether participants viewed genetic ancestry results online. Despite high levels of initial expressed interest in their genetic ancestry results, we observed challenges with engaging participants from typically underrepresented groups, including individuals without a high school degree, individuals living below the federal poverty level, and African Americans. In addition, it is important to note that, even after adjusting for education and living below the poverty level, African Americans were less likely to engage in our study than European Americans.

Because of the long-standing underrepresentation of African Americans and individuals with low socioeconomic status in medical studies, a stated mission of the PMI Working Group is that it will “ensure that people historically underrepresented in biomedical research are included in sufficient numbers to allow robust inferences in these groups.”2 The proposed method for recruitment of the PMI cohort is partnership with health-care provider organizations combined with direct volunteers, which may not adequately reach historically underrepresented groups. Although 90% of the general population has health insurance, only 69% of individuals without a high school education and 83% of individuals living below the poverty level have health insurance.12 Because of lower rates of health insurance among these underserved populations, recruitment of these individuals to the PMI cohort will be more difficult than recruiting from the general population. Our findings indicate that, even if underrepresented groups are successfully recruited into and express interest in the PMI cohort, the use of Internet-based technologies may pose an additional challenge to engagement among underrepresented groups.

In this study, participants were given at least 6 months to view their genetic ancestry results, and they were contacted multiple times in different ways to inform and remind them of the availability of their results. Using this approach, we were able to engage 45% of the European American participants with a high school education who were living above the poverty level. By contrast, we were able to engage only 18% of African American participants with a high school education who were living above the poverty level, 4% of participants without a high school education, and 10% of participants living in poverty. These results highlight the challenges of maintaining engagement of underrepresented groups using Internet-based methods. Previous studies suggest that personal contact, incentives, and community engagement have proven effective in recruiting and retaining minority populations.13,14 Adapting these strategies to include digital technologies is important for creating a cohort representative of all Americans.

This study is limited by the fact that our specific definition of “engagement” which limits the generalizability of our findings. However, aspects of this study, including e-mail-based login and website navigation, are common among Internet-based medical studies. A second limitation of the study is that participant interest was measured via a face-to-face interview and may be artificially inflated by participants’ responses based on their perceptions of what was desired by the interviewer.

Nonetheless, the results of this study have strong implications as we move forward with Internet-based approaches in medicine and research: Current health-care disparities may be magnified unless explicit efforts are made to increase participant engagement and retention among individuals with low levels of education and among underrepresented minorities.

Disclosure

L.J.B. is listed as an inventor on Issued U.S. Patent 8,080,371,“Markers for Addiction” covering the use of certain SNPs in determining the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of addiction. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Advisory Committee to the NIH Director. Digital health data in a million-person precision medicine initiative cohort. National Institutes of Health; 2015 https://www.nih.gov/sites/default/files/research-training/initiatives/pmi/pmi-workshop-20150528-summary.pdf.

Hudson K, Lifton R, Patrick-Lake B. The precision medicine initiative cohort program-building a research foundation for 21st century medicine. In: Precision Medicine Initiative (PMI) Working Group Report to the Advisory Committee to the Director, ed; 2015 http://acd.od.nih.gov/reports/DRAFT-PMI-WG-Report-9-11-2015-508.pdf.

Anderson N, Bragg C, Hartzler A, Edwards K. Participant-Centric Initiatives: Tools to Facilitate Engagement In Research. Appl Transl Genom 2012;1:25–29.

Kaye J, Curren L, Anderson N, et al. From patients to partners: participant-centric initiatives in biomedical research. Nat Rev Genet 2012;13:371–376.

Overby CL, Maloney KA, Alestock TD, et al. Prioritizing approaches to engage community members and build trust in biobanks: a survey of attitudes and opinions of adults within outpatient practices at the University of Maryland. J Pers Med 2015;5:264–279.

Kuang H, Jin S, Thomas T, et al.; Reproductive Medicine Network. Predictors of participant retention in infertility treatment trials. Fertil Steril 2015;104:1236–43.e1.

Couper MP, Alexander GL, Zhang N, et al. Engagement and retention: measuring breadth and depth of participant use of an online intervention. J Med Internet Res 2010;12:e52.

Perrin A, Duggin M. American’s Internet Access: 2000–2015. Pew Research Center; 2015 http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/06/26/americans-internet-access-2000-2015/.

Anderson M. Technology Device Ownership: 2015. http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/10/29/technology-device-ownership-2015. PEW Research Center; 2015.

Bass PF 3rd, Wilson JF, Griffith CH. A shortened instrument for literacy screening. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:1036–1038.

US Census Bureau. 2010–2014 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. American FactFinder. Tables generated by Sarah Hartz: http://factfinder2.census.gov. Accessed 22 February 2016.

Smith JC, Medalia C. Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2014. US Department of Commerce EaSA; 2015.

Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK. Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annu Rev Public Health 2006;27:1–28.

Nicholson LM, Schwirian PM, Klein EG, et al. Recruitment and retention strategies in longitudinal clinical studies with low-income populations. Contemp Clin Trials 2011;32:353–362.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants K08 DA032680, P01 CA089392, T32GM07200, UL1TR000448, TL1TR000449, and F30AA023685, UL1RR024992 and KLTRR024994 and by funds from the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hartz, S., Quan, T., Ibiebele, A. et al. The significant impact of education, poverty, and race on Internet-based research participant engagement. Genet Med 19, 240–243 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2016.91

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2016.91

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Assessing an Interactive Online Tool to Support Parents' Genomic Testing Decisions

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2019)

-

Most Current Smokers Desire Genetic Susceptibility Testing and Genetically-Efficacious Medication

Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology (2018)