Abstract

Desmosterolosis is a rare autosomal recessive disorder of elevated levels of the cholesterol precursor desmosterol in plasma, tissue and cultured cells. With only two sporadic cases described to date with two very different phenotypes, the clinical entity arising from mutations in 24-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR24) has yet to be defined. We now describe consanguineous Bedouin kindred with four surviving affected individuals, all presenting with severe failure to thrive, psychomotor retardation, microcephaly, micrognathia and spasticity with variable degree of hand contractures. Convulsions near birth, nystagmus and strabismus were found in most. Brain MRI demonstrated significant reduction in white matter and near agenesis of corpus callosum in all. Genome-wide linkage analysis and fine mapping defined a 6.75 cM disease-associated locus in chromosome 1 (maximum multipoint LOD score of six), and sequencing of candidate genes within this locus identified in the affected individuals a homozygous missense mutation in DHCR24 leading to dramatically augmented plasma desmosterol levels. We thus establish a clear consistent phenotype of desmosterolosis (MIM 602398).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aberrations of the final stages of cholesterol biosynthesis can lead to either Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome (SLOS) or to desmosterolosis, depending on the enzymatic defect in the pathway. Although the clinical entity of SLOS is well defined, that of desmosterolosis is yet unresolved. Human desmosterolosis (MIM 602398) is an autosomal recessive disorder of elevated levels of the cholesterol precursor desmosterol in plasma, tissue and cultured cells, stemming from mutations in 24-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR24). To date, only two clinical cases of this biochemical disorder have been described. Although DHCR24 mutations of both alleles were demonstrated in both cases,1 the clinical phenotypes of the two cases are very different. Through linkage analysis and biochemical studies of four individuals of a consanguineous Bedouin Israeli kindred, we now demonstrate a consistent phenotype of this rare human disorder.

Materials and methods

Patient's samples

Consanguineous Israeli Bedouin kindred (Figure 1) was clinically and genetically investigated. Clinical data of two deceased individuals (IV8, V10) was not available. The four surviving affected individuals of the kindred and 14 of their first-degree relatives (parents and siblings) were included in the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Soroka Medical Center and informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians.

Clinical evaluation

The medical records of all surviving four affected individuals were reviewed, and all had undergone careful clinical evaluation by a pediatric neurologist and a clinical geneticist followed by thorough biochemical laboratory testing and MRI.

Ruling out of homozygosity in loci of known genes

Homozygosity of affected individuals at loci of the genes known to be associated with inherited defects of white matter or agenesis of corpus callosum was tested using microsatellite markers as previously described.2 Microsatellite markers were derived from Marsheld maps. Intronic primer pairs were designed with the Primer3 (version 0.4.0) software (http://fokker.wi.mit.edu/primer3/), based on DNA sequences obtained from UCSC Genome Browser (sequences available on request). PCR products were separated on polyacrylamide gel using silver staining for detection.

Linkage analysis

Genome-wide scan was carried out using GeneChip Human Mapping 500K Array Set, Nsp Array containing 250 000 SNPs (Affymetrix, Fremont, CA, USA) according to the Affymetrix GeneChip Mapping Assay protocol as previously described.3 Genomic DNA (250 ng) from each subject was processed and labeled with reagents and protocols supplied by the manufacturer. Homozygosity by descent analysis was carried out using an in house tool for homozygosity mapping (Marcus et al, in preparation). Only one significant region on 1p33-1p32.3 was detected. Fine mapping of a locus on 1p33-1p32.3, haplotype analysis and elimination of candidate genes were performed by genotyping of additional microsatellite markers derived from Marsheld maps or novel markers designed based on Tandem Repeats Finder program and the UCSC Human genome database, in all affected individuals included in the study and their close relatives. Multipoint LOD score calculation using SUPERLINK4 (http://bioinfo.cs.technion.ac.il/superlink-online/) was carried out for markers D1S2720, D1S2134, D1S2824, D1S1616, D1S2748, D1S197, D1S427, Ch.1_51819Kb, D1S231, Ch.1_53080Kb, Ch.1_54036, Ch.1_54982, D1S200 and D1S2742 on 1p33-1p32.3 (markers Ch.153080Kb, Ch.154036Kb and Ch.154982Kb were designed using tandem repeats in UCSC genome browser. Sequences are available on request.). The calculations were carried out assuming an autosomal-recessive mode of inheritance with penetrance of 0.99, a disease mutant gene frequency of 0.01 and a uniform distribution of allele frequencies.

Sequence analysis

Genomic DNA of all participants was extracted from peripheral lymphocytes using standard methods.3 EBV transformation of lymphocytes of affected individuals was carried out as previously described.5 RNA was extracted from cultured cells of EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Petach Tikva, Israel) and cDNA was reverse transcribed by the Verso RT-PCR Kits (TAMAR, Mevaseret Zion, Israel) according to the protocol of the manufacturer.6 Primer pairs for cDNA and/or exons of genomic DNA (including flanking intron sequences) of eight genes in the putative 1p33-1p32.3 locus were designed based on the known mRNA and genomic sequences using Primer3. Primer sequences and PCR conditions are available on request. PCR products were directly sequenced using ABI PRISM 3730 DNA Analyser according to the protocols of the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Sequence variations were confirmed by bidirectional sequencing.

Mutation detection-restriction analysis

Testing for the DHCR24 mutation in the entire family and controls was carried out using restriction analysis, based on the fact that the mutation abrogates an AflIII restriction site. PCR amplification of genomic DNA using this primer set gave a 161 bp fragment, generating AflIII (NEB) differential cleavage products of the mutant (uncut, 161 bp) versus wild-type alleles (100 and 61 bp). Fragments were separated by electrophoresis on 3% agarose gel. PCR amplification primers: 5′-CTCACCCTCTGTCCTGTGGT-3′ and 5′-CCAGAATGTCCATCAGGTTG-3′.

Functional and biochemical assays

Cholesterol and desmosterol concentrations were determined in plasma collected from four family members: two fathers (obligatory healthy carriers of the DHCR24 mutation) and their affected sons. Plasma (10 μl) was processed together with 2 μg of deuterium labeled cholesterol as an internal standard.7 Following hydrolysis, lipid extraction and derivation, the samples were analyzed by gas chromatography mass spectrometry using the selected ion monitoring mode. The following ions were monitored: m/z 464 (deuterium labeled cholesterol), m/z 458 (cholesterol) and m/z 343 (desmosterol). Plasma from one of the affected sons was also processed for oxysterol analysis. This sample was run in scan mode to search for the presence of 27-hydroxydesmosterol.

Results

Clinical evaluation

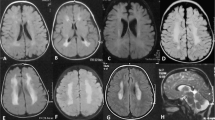

A consistent severe autosomal recessive neurological phenotype was identified in four individuals of large consanguineous Israeli Bedouin kindred (Figure 1). Four of the six affected individuals (Figure 1, individuals V1, V4, V7 and IV5) were alive and available for thorough clinical investigation. Failure to thrive, psychomotor retardation, microcephaly, micro-retrognathia and spasticity with variable degree of contractures of hands were seen in all patients, whereas severe convulsions near birth, as well as nystagmus and strabismus were evident in most. Brain MRI of all surviving affected individuals demonstrated significant reduction in white matter and partial or complete agenesis of corpus callosum (Table 1). Representative MRI images of two cases (V7, IV5) at age of 1.5 and 2 years are shown in Figure 2, demonstrating microcephaly (Figure 2a), a thin corpus callosum (Figures 2a and b), bilateral under-opercularization (Figure 2c) and enlarged ventricles (Figures 2d and e). In the posterior fossa, the brain stem was relatively small, whereas the vermis was normal in size and shape (Figure 2b). White matter paucity was noted both in the cerebrum and in cerebellar hemispheres (Figures 2d–f).

Linkage analysis

Four affected individuals (IV5, V1, V4, V7 and, Figure 1) and 14 healthy family members (parents and siblings of surviving affected individuals in Figure 1, excluding IV6 and IV7) were available for detailed clinical and mutational analyses. On the basis of consanguinity of the families studied, we assumed that the phenotype was a consequence of a founder effect. We first used polymorphic markers to test affected individuals for homoyozgosity in loci of genes known to be associated with inherited defects of white matter or agenesis of corpus callosum. Affected individuals were shown to be non-homozygous at the loci of MRPS16, SLC12A6, SPG11, EIF2B1-5, GALC, GFAP, NDUFV1 and ARSA, ruling out combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency-2 (COXPD2 (MIM 610498)), corpus callosum with peripheral neuropathy (ACCPN (MIM 218000)), spastic paraplegia-11 (SPG11 (MIM 604360)), leukoencephalopathy with vanishing white matter (MIM 603896), Krabbe disease (MIM 245200), Alexander disease (MIM 203450) and metachromatic leukodystrophy (MIM 250100; data not shown). We then proceeded to perform genome-wide linkage analysis of four patients, four obligatory carriers (parents of affected individuals) and one healthy sibling (IV1, IV2, V1, V2, IV3, III5, V4, V7 and IV5, depicted in Figure 1), using 250K SNP Arrays (GeneChip Human Mapping 500K Array Set (Affymetrix)) as previously described.3, 5 A single region of homozygosity on chromosome 1p33-1p32.3 was identified, that was common to all affected individuals. Fine mapping2, 6 testing the 18 available DNA samples with polymorphic markers narrowed down the locus to 6.75 cM (7.25 Mb) between D1S2824 and D1S200, with a maximum multipoint LOD score of six calculated using SUPERLINK4 (data not shown).

Mutation analysis

On the basis of our novel Syndrome to Gene (S2G) software,8 using EIF2B1 as a reference gene, the 62 genes within the disease-associated locus were prioritized. No mutation was found in the coding region and flanking intron sequences of the top seven candidate genes (data not shown). However, sequence analysis of the eighth candidate, DHCR24 (GenBank accession number NM_014762.3), revealed a novel missense mutation c.307C>T in exon 2 (Figure 3), which resulted in substitution of arginine to cysteine at amino acid 103 (p.R103C) adjacent to the flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) binding domain of the encoded protein. The mutation abolishes a recognition site of the restriction enzyme AflIII, allowing easy analysis of the entire kindred and controls. Analysis of all 18 DNA samples of the kindred was compatible with the mutation being associated with the disease phenotype, implying full penetrance (data not shown). The mutation was not found in any of 300 chromosomes from ethnically matched controls tested by restriction analysis.

The c.307C>T mutation in exon 2 of DHCR24. Sequence analysis is shown for an affected individual (a), an obligatory carrier (b) and an unaffected individual (c). (d) ClustalW sequence alignment of human DHCR24 to orthologs. The c.307C>T mutation (boxed) is in a residue that is highly conserved throughout evolution. Conserved residues are indicated with asterisks.

Functional and biochemical assays

DHCR24 encodes an FAD-dependent oxidoreductase expressed in the endoplasmic reticulum membrane, which catalyzes the reduction of the Δ-24 double bond of sterol intermediates during cholesterol biosynthesis. The protein contains a leader sequence that directs it to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Figure 3 demonstrates that R103 of DHCR24, which is altered in our patients, is extremely well conserved throughout evolution. Missense mutations in this gene have been associated with desmosterolosis. Of the entire kindred, only two fathers (IV1 and IV4, obligatory healthy carriers of the DHCR24 mutation) and their affected sons (V1 and V7) were willing to undergo biochemical analysis. We thus went on to measure plasma sterol levels, cholesterol and desmosterol concentrations in plasma collected from these four family members. The healthy carriers had normal levels of cholesterol relative to control (Table 2). Their desmosterol levels were also in the same range as the control. However, when calculated as percentage of total sterols, desmosterol in these carriers was about twice that found in the control. The two affected males had slightly lower cholesterol levels than the control and their carrier fathers. This may be because of their age rather than their condition. However, their desmosterol levels were markedly increased when compared to both the control and their carrier fathers. Although desmosterol made up ∼0.1% of total sterols in the carrier fathers, the corresponding fraction in their affected sons was 3.4 and 10.1%, respectively. Thus, although affected individuals and carriers had normal cholesterol levels, there were ∼120-fold increased levels of plasma desmosterol in affected individuals and 1.5-fold increased levels in carriers, proving deficient activity of 24-dehydrocholesterol reductase.

Discussion

Cholesterol accounts for 99% of all sterols in mammals, and is essential as a major constituent of membranes, a precursor to numerous signaling molecules, and an inducer of the Hedgehog family of morphogens. Cholesterol can be synthesized via two immediate precursors, 7-dehydrocholesterol or desmosterol. The involvement of cholesterol in embryonic development and morphogenesis through its role in the hedgehog protein signal transduction pathways provides a potential key to the pathogenesis of cholesterol-associated disorders.9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Human defects in the 7-dehydrocholesterol pathway leading to SLOS (MIM 270400) have been well described. Far less common are human defects in DHCR24, encoding the enzyme 3β-hydroxysterol Δ24-reductase, which catalyses the reduction of desmosterol to form cholesterol. To date, two Dhcr24 null mutant mouse lines have been generated in which cholesterol synthesis is blocked leading to desmosterol accumulation. The lines are on different genetic backgrounds, presenting at first with different phenotypes. Dhcr24−/− mice generated by Wechsler et al14 were viable up to adulthood without gross abnormalities, aside from being smaller than their wild-type counterparts and infertile because of the lack of cholesterol derived sex hormones. However, in a later study with a Dhcr24−/− mouse strain derived from the strain generated by Wechsler et al, most of the mice died prenatally or early postnatally.7 Dhcr24−/− mice generated by Mirza et al15 also died within early postnatal days. Their skin was wrinkleless, movement was restricted and the stomach was always empty. Histological examination of skin revealed features of lethal restrictive dermopathy.

To date, only two clinical cases of desmosterolosis (MIM 602398) have been described, and DHCR24 mutations of both alleles were demonstrated in both cases.1 The phenotypes of the two cases are very different, leaving the question of the desmosterolosis phenotype unresolved. FitzPatrick et al16 reported a case of an infant with multiple lethal congenital malformations in whom there was generalized accumulation of desmosterol and relative deficiency of cholesterol. The newborn (born week 34, died shortly after birth) had macrocephaly, hypoplastic nasal bridge, thick alveolar ridges, gingival nodules, cleft palate, total anomalous pulmonary venous drainage, ambiguous genitalia, short limbs and generalized osteosclerosis. The brain showed an immature gyral pattern with poor development of the corpus callosum and gross dilatation of the ventricles. The frontal lobes were disproportionately large and firm and the occitpital lobes were small. Abnormal accumulation of desmosterol was demonstrated in the kidney, liver and brain. Higher than normal levels of the same sterol were detected in plasma samples obtained from both parents.

The only other case of desmosterolosis in the literature17 is of a boy (born at term) with microcephaly, agenesis of the corpus callosum, downslanting palpebral fissures, bilateral epicanthal folds, submucous cleft palate, micrognathia, mild contractures of the hands, bilateral clubfeet, cutis aplasia and persistent patent ductus arteriosus. At 40 months of age, he was severely developmentally delayed and had failure to thrive. Radiological examination disclosed neither rhizomelic shortness nor osteosclerosis. Plasma sterol quantification at 2 years of age demonstrated normal cholesterol levels but a 100-fold increase in desmosterol. Both parents had mildly increased levels of desmosterol in plasma, consistent with heterozygosity for DHCR24 deficiency. Analysis of sterol metabolism in cultured transformed lymphoblasts showed a 100-fold increased level of desmosterol and a moderately decreased level of cholesterol in the cells the of the patient and a 10-fold elevation of desmosterol in the cells of the mother.

The phenotype of the four cases presented here is consistent and thus establishes a clear human desmosterolosis phenotype. Similar to the case described by Andersson et al,17 our patients had microcephaly with agenesis of corpus callosum, as well as failure to thrive. Most of the affected individuals had also convulsions, nystagmus and strabismus, and micrognathia as well as mild-to-severe contractures of the hands (Table 1). However, other features seen in the previous report (downslanting palpebral fissures, bilateral epicanthal folds, submucous cleft palate, bilateral clubfeet, cutis aplasia and patent ductus arteriosus) were absent in our patients, and are thus not essential features of the desmosterolosis phenotype. The case reported by FitzPatrick et al16 has some features in common with the phenotype we report. However, its clinical presentation is far more severe, either because of the higher desmosterol levels, or representing a wider defect beyond desmosterolosis.

The novel homozygous DHCR24 mutation found in the kindred we describe is a missense mutation in an extremely conserved amino acid that is immediately adjacent to the FAD-binding domain of the protein. The homozygous mutation in the case of Andersson et al17 is in a less conserved amino acid that is within the same domain, perhaps explaining the partial similarity in the phenotype. In contrast, compound heterozygous mutations seen in the phenotypically less similar case described by FitzPatrick et al16 are in amino acids that are far less conserved and that are remote from the FAD-binding domain. It remains unclear whether the case of FitzPatrick et al has a phenotype different than the other cases only because of the dissimilar mutations, or because the patient had additional unidentified molecular defects. It is of interest to note that in another cholesterol pathway disease, SLOS, various mutations in the same gene cause a large scope of clinical phenotypes: severe biochemical disorder causes a lethal malformation syndrome, whereas milder missense mutations can present as minimally dysmorphic children with learning disability.18 As suggested by Andersson et al,17 the central nervous system anomalies seen in desmostrolerosis may be due to impaired sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling which is known to require adequate cellular levels of cholesterol for normal function. The phenotypic variability of desmosterolosis might thus be due to different degrees of perturbations of the SHH pathway.

Accession codes

References

Waterham HR, Koster J, Romeijn GJ et al: Mutations in the 3-beta-hydroxysterol delta-24-reductase gene cause desmosterolosis, an autosomal recessive disorder of cholesterol biosynthesis. Am J Hum Genet 2001; 69: 685–694.

Birnbaum RY, Zvulunov A, Hallel-Halevy D et al: Seborrhea-like dermatitis with psoriasiform elements caused by a mutation in ZNF750, encoding a putative C2H2 zinc finger protein. Nat Genet 2006; 38: 749–751.

Khateeb S, Flusser H, Ofir R et al: PLA2G6 mutation underlies infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet 2006; 79: 942–948.

Silberstein M, Tzemach A, Dovgolevsky N, Fishelson M, Schuster A, Geiger D : Online system for faster multipoint linkage analysis via parallel execution on thousands of personal computers. Am J Hum Genet 2006; 78: 922–935.

Narkis G, Ofir R, Landau D et al: Lethal contractural syndrome type 3 (LCCS3) is caused by a mutation in PIP5K1C, which encodes PIPKI gamma of the phophatidylinsitol pathway. Am J Hum Genet 2007; 81: 530–539.

Narkis G, Ofir R, Manor E, Landau D, Elbedour K, Birk OS : Lethal congenital contractural syndrome type 2 (LCCS2) is caused by a mutation in ERBB3 (Her3), a modulator of the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/Akt pathway. Am J Hum Genet 2007; 81: 589–595.

Heverin M, Meaney S, Brafman A et al: Studies on the cholesterol-free mouse. Strong activation of LXR-regulated hepatic genes when replacing cholesterol with desmosterol. Arterioscl Thromb Vasc Biol 2007; 27: 2191–2197.

Gefen A, Cohen R, Birk OS : Syndrome to gene (S2G): in-silico identification of candidate genes for human diseases. Hum Mutat 2010; 31: 229–236.

Porter JA, Young KE, Beachy PA : Cholesterol modification of hedgehog signaling proteins in animal development. Science 1996; 274: 255–259.

Hammerschmidt M, Brook A, McMahon AP : The world according to hedgehog. Trends Genet 1997; 13: 14–21.

Mann RK, Beachy PA : Cholesterol modification of proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 2000; 1529: 188–202.

McMahon AP : More surprises in the Hedgehog signaling pathway. Cell 2000; 100: 185–188.

Villavicencio EH, Walterhouse DO, Iannaccone PM : The Sonic hedgehog–Patched–Gli pathway in human development and disease. Am J Hum Genet 2000; 67: 1047–1054.

Wechsler A, Brafman A, Shafir M et al: Generation of viable cholesterol-free mice. Science 2003; 302: 2087.

Mirza R, Hayasaka S, Takagishi Y et al: DHCR24 gene knockout mice demonstrate lethal dermopathy with differentiation and maturation defects in the epidermis. J Invest Dermatol 2006; 126: 638–647.

FitzPatrick DR, Keeling JW, Evans MJ et al: Clinical phenotype of desmosterolosis. Am J Med Genet 1998; 75: 145–152.

Andersson HC, Kratz L, Kelley R : Desmosterolosis presenting with multiple congenital anomalies and profound developmental delay. Am J Med Genet 2002; 113: 315–319.

Porter FD : Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Eur J Hum Genet 2008; 16: 535–541.

Acknowledgements

We thank the ISF-Morasha Legacy Heritage Fund and the Morris Kahn Family Foundation for the generous support of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Web Resources

Chromas: http://www.technelysium.com.au/chromas.html

Conseq server: http://conseq.bioinfo.tau.ac.il/

HaploPainter: http://haplopainter.sourceforge.net/index.html

NEBcutter V2.0: http://tools.neb.com/NEBcutter2/

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/

Primer3, (v. 0.4.0) Pick primers from a DNA sequence: http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3/

Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool (SMART): http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/

Superlink online version 1.5: http://bioinfo.cs.technion.ac.il/superlink-online/

Syndrome to Gene (S2G): http://fohs.bgu.ac.il/s2g/

UCSC Genome Browser website: http://genome.ucsc.edu/

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zolotushko, J., Flusser, H., Markus, B. et al. The desmosterolosis phenotype: spasticity, microcephaly and micrognathia with agenesis of corpus callosum and loss of white matter. Eur J Hum Genet 19, 942–946 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2011.74

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2011.74

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

DHCR24 reverses Alzheimer’s disease-related pathology and cognitive impairment via increasing hippocampal cholesterol levels in 5xFAD mice

Acta Neuropathologica Communications (2023)

-

The role of DHCR24 in the pathogenesis of AD: re-cognition of the relationship between cholesterol and AD pathogenesis

Acta Neuropathologica Communications (2022)

-

Retinoic acid-induced 1 gene haploinsufficiency alters lipid metabolism and causes autophagy defects in Smith-Magenis syndrome

Cell Death & Disease (2022)

-

Inclusion of endophenotypes in a standard GWAS facilitate a detailed mechanistic understanding of genetic elements that control blood lipid levels

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Subcellular localization of sterol biosynthesis enzymes

Journal of Molecular Histology (2019)