Climate change can cause anxiety — researchers need to work out when that requires specialist help.Credit: Kyle Grillot/Bloomberg/Getty

Nearly one billion people worldwide — including one in seven teenagers — have a mental disorder. A growing body of research suggests that climate change is worsening people’s mental health and emotional well-being. Acute heatwaves, droughts, floods and fires fuelled by climate change cause trauma, mental illness and distress. So can chronic effects of global warming, such as water and food insecurity, community breakdown and conflict, as we report in a News feature.

The rise of eco-anxiety: scientists wake up to the mental-health toll of climate change

Surveys are revealing that experiencing the effects of climate change — and awareness of the threat — can lead to psychological responses such as a chronic fear of environmental doom, known as eco-anxiety. Eco-distress, climate anxiety and climate grief are other terms used. In a 2021 survey of 10,000 people aged 16–25 in 10 countries, nearly 60% of respondents were highly worried about climate change, and more than 45% said their feelings about climate change affected their daily lives, such as their ability to work or sleep1.

Make the problem visible

Such reactions to an existential threat are expected, and many people can handle these feelings on their own — but some need specialist help. Although there is anecdotal evidence that people with eco-anxiety are increasingly going to clinics, the psychological toll of climate change tends to be invisible — one reason why it has been neglected.

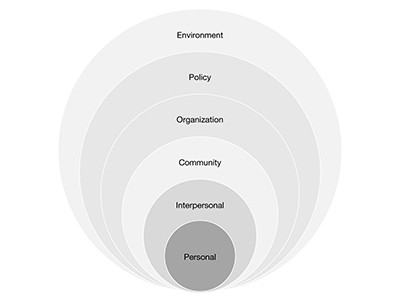

Researchers and governments need better ways to measure the wide-ranging extent of climate change’s effects on mental health. Data scientists, climate scientists and climate-attribution researchers, among others, should join mental-health researchers in furthering the underlying science. Mental-health professionals also need training and support to provide help. Mental illness is already underdiagnosed and stigmatized, and mental health care in most countries is shockingly insufficient. Climate change makes the case for addressing this crisis even more urgent.

Greener cities: a necessity or a luxury?

One key challenge for researchers is measuring the mental-health burden attributable to climate change and tracking it over time. Most research so far has been conducted in high-income countries, despite low- and middle-income countries experiencing the harshest effects of the warming planet. The day-to-day experiences of people in marginalized groups and Indigenous communities must also be captured.

Much research on climate and mental health has focused on one end of the spectrum of mental health — such as clinical diagnoses, emergencies or suicides2. But when around half the global population lives in nations with one psychiatrist per 200,000 people, it is no surprise that many conditions are undiagnosed and undocumented. Better monitoring and sharing of clinical mental-health data are needed. Researchers must develop and track standardized ways to measure milder or more fleeting forms of eco-anxiety and distress that fall outside standard diagnoses, and work out when interventions are needed.

A call to action

Some steps are already being taken. Researchers are, for instance, trying to develop global mental-health indicators that can be linked to weather and climate data, as part of the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change, a collaboration of specialists from more than 50 academic institutions and United Nations agencies. The group welcomes collaborators to further this work, says Kelton Minor, a research scientist at Columbia University’s Data Science Institute in New York City who is leading the collaboration’s effort on climate and mental health.

Making cities mental health friendly for adolescents and young adults

A top priority must be developing and evaluating ways to effectively reduce climate change’s mental-health burden while strengthening the resilience of communities that are particularly at risk. Existing tools and treatments — such as cognitive behavioural therapy, which helps people to challenge unhelpful thoughts and behaviours — will be part of the solution. Some studies suggest that, for individuals, taking action to combat climate change could also help to manage their eco-anxiety3: a double win.

The problem amounts to a call to action on all fronts. The constant drip of research adding to evidence of a climate crisis — as well as leaders’ inaction — is itself probably a source of eco-anxiety and frustration. More than 55% of young people in the 2021 survey said that climate change made them feel powerless, and 58% that their government had betrayed them and future generations1.

Those who experience debilitating effects on their mental health caused by climate change need help from specialists. The many others who are scared or angry, but otherwise not unwell, need to know that these feelings are normal — and if they can harness their unease to spur action, they could help themselves, others and the world.

At the same time, it must also be recognized that world leaders’ inaction is a cause of distress — and action by governments is what is needed to soothe it.

The rise of eco-anxiety: scientists wake up to the mental-health toll of climate change

The rise of eco-anxiety: scientists wake up to the mental-health toll of climate change

Greener cities: a necessity or a luxury?

Greener cities: a necessity or a luxury?

Making cities mental health friendly for adolescents and young adults

Making cities mental health friendly for adolescents and young adults

A giant fund for climate disasters will soon open. Who should be paid first?

A giant fund for climate disasters will soon open. Who should be paid first?

I’m a climate scientist. Here’s how I’m handling climate grief

I’m a climate scientist. Here’s how I’m handling climate grief