Every year for six years, Laureen Wamaitha hoped that her fields in Kenya would flourish. Every year, she’d see drought wither the crops and then floods wash them away. The cycle of optimism and loss left her constantly anxious, and she blamed climate change. “You get to a situation where you have panic attacks because you’re always worried about something,” she says.

Medical student Vashti-Eve Burrows, meanwhile, saw powerful hurricane Dorian rage through the Bahamas in 2019 and now she is fearful about the future of the country, an island archipelago that is vulnerable to sea-level rise and storms. “Will there even be a Bahamas in maybe 20 to 30 years?” she says.

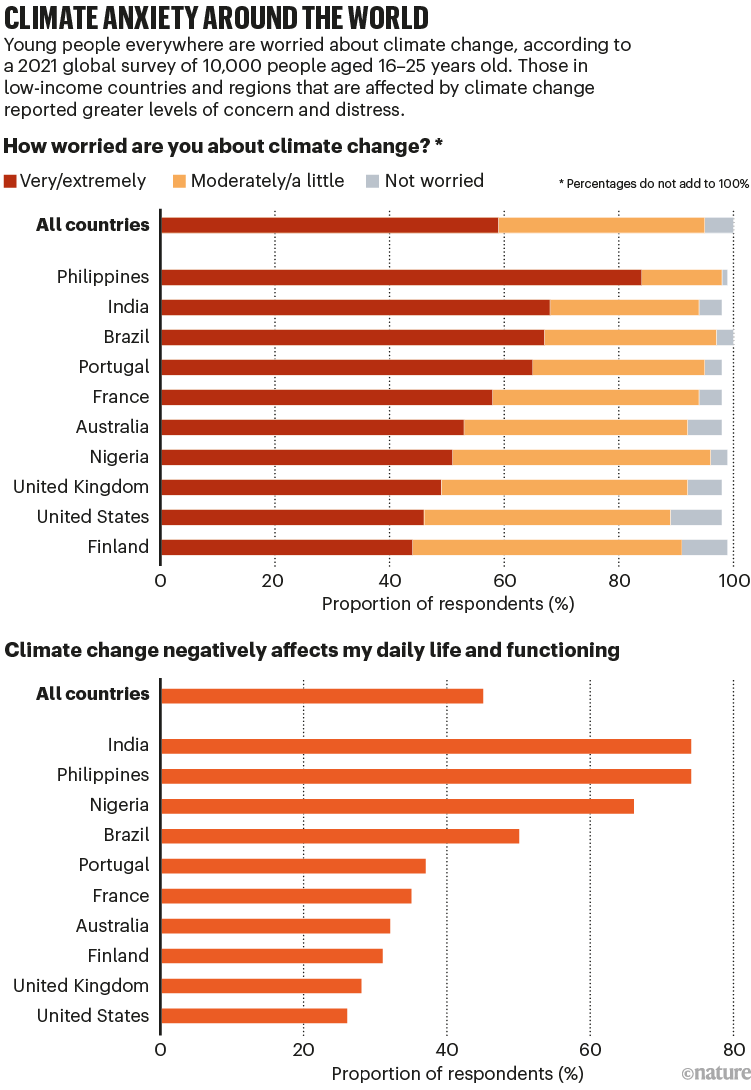

Wamaitha and Burrows are part of a growing chorus of people speaking up about the impacts of climate change on mental health. Climate change is exacerbating mental disorders, which already affect almost one billion people and are among the world’s biggest causes of ill health. A global survey in 2021 found that more than half of people aged 16–25 felt sad, anxious or powerless, or had other negative emotions about climate change1. Altogether, hundreds of millions of people might be experiencing some type of negative psychological response to the climate crisis.

What happens when climate change and the mental-health crisis collide?

Scientists say the topic has been sorely neglected, but is leaping up the research agenda. “I’ve seen an explosion of research in the last five years for sure. That’s been very exciting,” says Alison Hwong, a psychiatrist and mental-health researcher at the University of California, San Francisco. The growing severity of heat, hurricanes and other impacts mean “it’s impossible to ignore”, she says.

Researchers want to unpick the many pathways by which climate change affects mental health, from trauma caused by hurricanes, floods, droughts and fires to ‘eco-anxiety ’— a chronic fear of environmental doom. Studies on methods that can help people prevent or manage these problems are also needed, although some work suggests that climate action and activism might help.

A seam of climate injustice is exposed by the research. Young people are likely to experience the greatest mental burden from climate change that older generations have caused. Groups of people that already experience poverty, illness or inequalities are most at risk of deteriorating mental health. “Climate change exacerbates already existing economic situations, where it’s the poorer people who are feeling even worse,” says Jennifer Uchendu, a researcher, climate activist and founder of SustyVibes, an environmental group based in Lagos, Nigeria.

Mental-health toll

The fact that climate change affects people’s mental health is not surprising: what’s new is the attention the issue is attracting — and the myriad ways that scientists are documenting its varied and sometimes shocking effects.

It is well known that extreme weather events and disasters can have an immediate traumatic impact — as well as “a long tail of mental-health conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, substance abuse,” says Emma Lawrance, who studies mental health at Imperial College London. Also taking a mental-health toll in vulnerable countries are less sudden — but nonetheless devastating — disruptions caused by global warming’s impacts, such as forced migration, loss of livelihoods, food insecurity and community breakdown.

Research on how climate-change impacts, such as drought, affect mental health is growing.Credit: Simone Boccaccio/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty

There is evidence that directly experiencing higher temperatures can worsen mental health. A 2018 study of suicide data from the United States and Mexico over two or more decades showed that suicide rates rose by 0.7% in the United States and 2.1% in Mexico, with a 1 °C increase in average monthly temperature2. The researchers projected an extra 9,000–40,000 suicides by 2050 in the two countries if no action was taken against climate change. Other work has shown that higher temperatures are linked to poor sleep — which can in turn contribute to mental distress3.

Studies also suggest that people with existing mental illness are at greater risk of dying during extreme heat4, but “understanding why that is and what we can do to stop it is really unexplored”, Lawrance says. One potential explanation is that some psychiatric drugs can interfere with the body’s response to heat5.

Eco-anxiety goes global

Another striking field of research examines how the awareness of climate change and its impacts can lead to concern or distress, a phenomenon sometimes called eco-anxiety, eco-distress, climate grief or solastalgia (distress linked to environmental change). In a 2018 survey, 72% of people aged 18–34 said that negative environmental news stories affected their emotional well-being, such as by causing anxiety, racing thoughts or sleep problems (see go.nature.com/3vbbt7p). A 2020 survey6 in the United Kingdom found that young people aged 16–24 reported more distress from climate change than from COVID-19.

A few years ago, such ‘eco-emotions’ were sometimes dismissed as fretting of the ‘worried-well’ in high-income countries, Lawrance says. But research that shows the global reach of these feelings is challenging that view. The 2021 survey1 was the biggest so far on climate anxiety and included 10,000 children and young people in 10 countries. More than 45% of respondents said that worry about climate change had a negative impact on eating, working, sleeping or other aspects of their daily lives. Reports of climate change affecting people’s ability to function were highest in the Philippines, India and Nigeria and lowest in the United States and United Kingdom — contradicting the idea that eco-anxiety is just a rich-country problem (see ‘Climate anxiety around the world’).

Source: Ref. 1

For some, eco-anxiety might be linked to first-hand experience of climate-related devastation. The fact that young people in the Philippines reported some of the highest levels of worry was no surprise to John Jamir Benzon Aruta, an environmental psychologist at De La Salle University in Manila. In 2013, he saw first-hand the devastation and trauma caused in the Philippines by Typhoon Haiyan — one of the most powerful tropical cyclones ever recorded. “You see houses, communities devastated. You also see corpses all over the place,” he says. “Just witnessing the aftermath made me feel traumatized.”

But the 2021 survey documented widespread distress that went beyond those who were immediately affected by extreme climate events. Around 75% of respondents said that climate change made them think the future is frightening and 56% said that it made them think that humanity is doomed. People who felt their government was failing to act on climate issues were more likely to feel eco-distress.

Are we all doomed? How to cope with the daunting uncertainties of climate change

Climate change isn’t the first existential crisis that humanity has faced. But researchers point out that it is different from some other threats: it is happening now rather than being a future risk, such as a nuclear war; it’s affecting the entire globe at once; and many people feel angry that they have to bear the brunt of climate change that other people have caused.

Feelings of eco-anxiety are not necessarily a sign of dysfunction. “If you are under immediate threat, it is a realistic, rational, healthy survival instinct to react by being anxious or to experience fear,” says Elizabeth Marks, a clinical psychologist at the University of Bath, UK, and one of the survey’s lead authors. It could even be harmful to think of these feelings as a disorder. “If we think of it as a diagnosable condition, that risks placing the blame on the individual as having an unhealthy response,” she says. That said, some people might become so impaired by their eco-distress that they would benefit from psychological help.

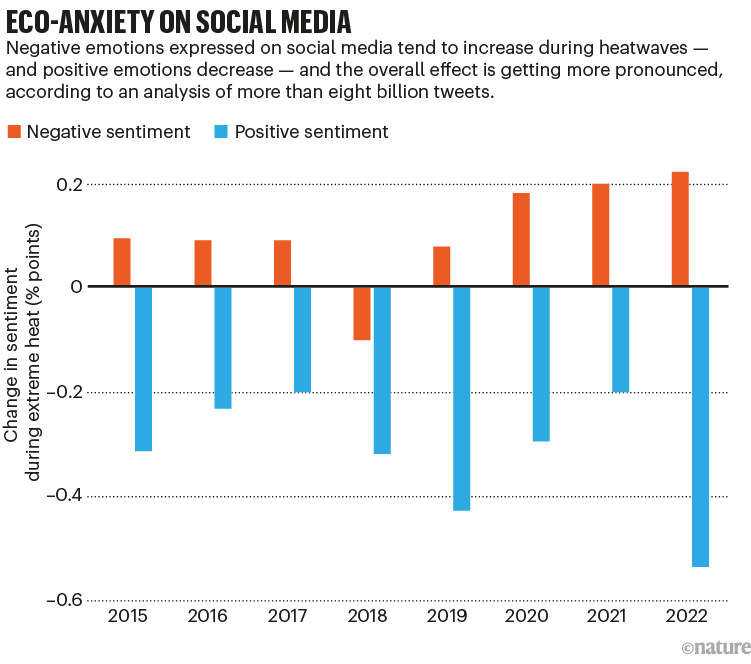

Social media is being used to monitor negative feelings linked to climate change. In 2023, Kelton Minor, a research scientist at Columbia University’s Data Science Institute in New York and Nick Obradovich, a climate mental-health researcher at the Laureate Institute for Brain Research in Tulsa, Oklahoma, reported an analysis of more than eight billion posts on Twitter (now known as X) that appeared between 2015 and 2022 from people who had opted to share their geolocation data. (The analysis was part of a wider report on health and climate change7.) The researchers analysed the tweets for positive words (such as good, well, new and love) and negative ones (bad, wrong, hate and hurt), and linked them to climate data from the tweeters’ locations. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the team found that heatwaves and extreme rainfall increased negative feelings and decreased positive ones compared with control days without extreme weather in the same place and time of year. They also found that these negative reactions became worse over the years (see ‘Eco-anxiety on social media’).

Source: Ref. 7

Beyond the Western view

The full effects of climate change on mental health are hard to measure. A combination of factors, including the stigma around mental health and lack of access to health-care services, mean that many people with mental-health concerns go undiagnosed. When Wamaitha talked to her family in Kenya about how worried she was, they’d say: “It’s not a big deal, it’s part of life,” she says. Anxiety and depression are barely recognized as disorders in her region, she says. Mental-health services are scarce and older people just “think that you’re very sensitive” because they survived droughts in the past. In the 2021 survey, nearly 40% of young people worldwide said their concerns about climate change had been ignored or dismissed.

Climate change is also a health crisis — these 3 graphics explain why

Researchers are particularly worried that countries and regions that experience the harshest effects of climate change are where the least climate mental-health research has been done. In her studies, Uchendu found that most research was Western-centric. “Not a lot of people were talking about these issues in Africa,” she says. In 2022, she started the Eco-anxiety in Africa Project, which, in collaboration with the University of Nottingham, UK, has documented the emotional turmoil that heat and erratic weather has created for people living in five African cities.

Another question researchers have is how context and culture affect climate anxiety. Some studies have shown that “connection to country” — through cultural practices such as hunting and gathering food — is important to the mental health and well-being of some Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islander communities8, says Michelle Dickson, who studies the mental health of Indigenous Australians at the University of Sydney, Australia. But rising sea levels, drought and bushfires threaten those practices. Tools used in health-care settings “rarely take into account the important cultural values that underpin Indigenous mental health”, says Dickson, who is a Darkinjung/Ngarigo Australian Aboriginal.

Dickson is now co-leading a project to empower communities to design their own climate action plans — allowing researchers to test whether doing this could improve people’s mental health.

Heatwaves — such as one that hit New Delhi in 2022 — can worsen mental disorders and are linked to increased negative feelings.Credit: Kabir Jhangiani/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty

Overcoming eco-distress

Addressing climate-fuelled mental-health conditions will be a colossal task when mental-health care globally is already poor: only around 3% of people with depression receive adequate treatment in low- and lower-middle-income countries, and 23% in high-income countries9. Lawrance says that many communities are finding their own ways to cope, but that the effectiveness of these efforts is rarely studied and shared. “There’s a massive gap around evaluation,” she says.

Some evidence suggests that taking action to combat climate change can help people to manage eco-anxiety. “There does seem to be an argument for supporting people to take collective action,” says Marks, such as joining campaign groups with like-minded people. It’s also important to “recognize that I feel this way because I care”, she says. “These climate emotions are actually something to be honoured and allowed, not pushed away.” Marks also suggests that some people who are feeling eco-distress limit the amount of time they spend ‘doom-scrolling’ through climate news.

Extreme heat harms health — what is the human body’s limit?

Researchers are starting to take collective action themselves. Last month, the Connecting Climate Minds project, one of the most ambitious research efforts in the field of climate-related mental health10, released a series of regional ‘research and action’ priorities, including, for example, to understand how climate change compounds the stress of wars, violence and disease epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa. The project includes researchers, policymakers and people with first-hand experience of climate change. Uchendu says that in one of the meetings, someone joining remotely was standing in flood water in their room. “It was mind-blowing,” she says.

Wamaitha, who along with Burrows is one of many people who shared their experiences with Connecting Climate Minds, has turned some of her concerns into action. Last year, after trying and failing to grow drought-resistant crops, she quit farming and is now working at a non-governmental organization in Bura, Kenya, that is focused on poverty relief. She is earning enough to study for a master’s degree in public health, and she raises awareness of global health on the social-networking site LinkedIn. But she is anxious about the future and worries about whether to have children. “I don’t think I am in a good environment to be able to bring kids into this particular place,” she says. “That is the saddest thing when I think about it.”

Burrows, who is studying medicine at the University of the West Indies in Saint Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago, says she chooses to be positive and does small things to help the environment, such as walking instead of driving. She says that she prays that wealthy countries and companies “will really, truly understand what is happening and not just say smooth words to try to pacify us in the moment”. They should act to “help the smaller countries and the world at large”, she says.

What happens when climate change and the mental-health crisis collide?

What happens when climate change and the mental-health crisis collide?

Are we all doomed? How to cope with the daunting uncertainties of climate change

Are we all doomed? How to cope with the daunting uncertainties of climate change

Extreme heat harms health — what is the human body’s limit?

Extreme heat harms health — what is the human body’s limit?

Climate change is also a health crisis — these 3 graphics explain why

Climate change is also a health crisis — these 3 graphics explain why

Earth just had its hottest year on record — climate change is to blame

Earth just had its hottest year on record — climate change is to blame