Abstract

Background:

Tetracycline is a photosensitising medication that increases skin vulnerability to UV-related damage.

Methods:

We prospectively examined tetracycline use and risk of incident melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and basal cell carcinoma (BCC) based on 213 536 participants from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), NHS2, and Health Professionals Follow-up Study. Information on ever use of tetracycline was asked via questionnaire. Diagnoses of melanoma and SCC were pathologically confirmed.

Results:

Tetracycline use was associated with a modestly increased risk of BCC (ncase=36 377), with a pooled hazard ratio (HR) of 1.11 (95% confidence interval (CI)=1.02–1.21, P-trend=0.05 by duration of use). Tetracycline use was not significantly associated with melanoma (ncase=1831, HR=1.09, 95% CI=0.94–1.27) or SCC (ncase=3332, HR=1.04, 95% CI=0.91–1.18) risk overall. However, we observed positive interactions between tetracycline use and adulthood UV exposure on SCC risk (P-interaction=0.05).

Conclusion:

Tetracycline use was associated with a modestly increased risk of BCC, but was not associated with melanoma or SCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Excessive sun exposure and UV radiation is the most recognised risk factor for skin cancer (Li et al, 2016). Individuals with a sun-sensitive phenotype, such as sunburn susceptibility and poor tanning ability, have significantly increased risk of melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and basal cell carcinoma (BCC) (Li et al, 2016). Tetracycline is known to induce photosensitivity, specifically phototoxic dermatoses, increasing the vulnerability of the epidermis and dermis to UV-induced damage (Stern, 1998; Drucker and Rosen, 2011). Tetracycline may therefore act as a co-carcinogen with UV radiation and increase the risk of skin cancer. Only a limited number of epidemiologic studies have been published on tetracycline use and skin cancer (Kaae et al, 2010; Robinson et al, 2013). Although these studies suggest a possible association between tetracycline use and particularly BCC risk, whether tetracycline use may increase the risk of all skin cancer types remain to be elucidated. We prospectively examined the associations between tetracycline use and risk of incident melanoma, SCC, and BCC in two cohorts of women, the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and NHS2, and a cohort of men, the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS).

Materials and methods

Study population

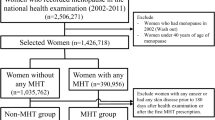

Details of the three cohorts are presented in the Supplementary Information. In 1982 (NHS) and 1992 (HPFS), participants were asked ‘did you ever take tetracycline for at least 2 months at a time (e.g., for acne or other reason)’ and for how long they had used tetracycline. In 1993 (NHS2), participants were asked whether they had ever taken tetracycline (without specifying ‘at least two months’) and for how long they had used tetracycline. In 2006, we sent a supplementary questionnaire to 100 HPFS participants (50 reported ⩾4 years of use and 50 reported <4 years) and asked the indications for tetracycline use. Of them, 83 returned the completed questionnaire, with acne (51.8%, 43 out of 83) and rosacea (19.3%, 16 out of 83) reported as the primary indications. Only 12.0% (10 out of 83) denied or could not remember using tetracycline for ⩾2 months (Sutcliffe et al, 2007).

Participants reported diagnoses of melanoma, SCC, and BCC on biennial surveys. Related medical records for melanoma and SCC were reviewed and only pathologically confirmed invasive cases were included in our analysis. The BCC diagnoses were not confirmed but previous studies have indicated high validity of self-reports (Colditz et al, 1986; Hunter et al, 1992).

Among participants with information on tetracycline use, we excluded those reporting any cancer at or before the baseline (1982 in NHS, 1993 in NHS2, and 1992 in HPFS) and all non-whites.

Statistical analysis

Person-years of follow-up were calculated from the return of the baseline questionnaire to the diagnosis date of melanoma, SCC, or BCC, death, or end of follow-up (June 2012 for NHS, June 2011 for NHS2, and Jan 2010 for HPFS), whichever came first. We calculated age- and multivariate-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using Cox proportional hazards analysis stratified by age and calendar time in each 2-year interval. Covariates in the multivariate-adjusted models are shown in the Supplementary Information. To address the concern of confounding by indication, we conducted sensitivity analyses by additionally adjusting for indications for tetracycline (history of periodontal disease in NHS/HPFS; severe teenage acne, adulthood severe acne, and rosacea in NHS2) or excluding those reporting these conditions. We examined whether UV exposure (ambient erythemal UV radiation, a measure of both UVA and UVB) or sun-sensitive phenotypes modified the associations between tetracycline use and skin cancer risk (Supplementary Information online). Stratified analyses were also conducted by body sites of melanoma/SCC and Breslow thickness of melanoma. Heterogeneity tests were conducted using Q statistics. We used random-effect meta-analysis models to get pooled HRs across the three cohorts.

Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All P-values were two tailed with the significance level set at P<0.05.

Results

A total of 213 536 participants were included (Table 1). The mean (s.d.) age was 48.4 (7.2) years in NHS, 38.1 (47.1) years in NHS2, and 59.0 (9.5) years in HPFS at baseline. Tetracycline users tended to have more severe or blistering sunburns and had higher UV exposure.

We identified 1831 melanoma cases during follow-up. We did not find significant associations between risk of incident melanoma and either ever tetracycline use (multivariate-adjusted pooled HR=1.11, 95% CI=0.95–1.29), or duration of use (P-trend=0.33, Table 2).

A total of 3332 SCC and 36 377 BCC cases were documented during follow-up. Ever tetracycline use was significantly associated with modestly increased risk of BCC, with a pooled HR of 1.11 (95% CI=1.02–1.21). The association appeared stronger in NHS (HR=1.20, 95% CI=1.13–1.28) than NHS2/HPFS and was not statistically significant in HPFS. There was a trend towards elevated BCC risk with increasing duration of use (P-trend=0.05; Table 3). Although we did not find a significant association for SCC overall (HR=1.04, 95% CI=0.91–1.18), we observed positive interactions between tetracycline use and UV exposure in adulthood on SCC risk (pooled P-interaction=0.05); the HR (95% CI) of SCC risk associated with tetracycline was 0.89 (0.73–1.10) for the lower half of UV exposure and 1.17 (0.99–1.40) for the upper half of UV exposure. We did not find significant modifications of SCC risk by sun-sensitive phenotypes, nor did we find any interactions for risk of BCC or melanoma. In stratified analyses, we did not find significant heterogeneity between tetracycline and melanoma risk by body sites or Breslow thickness of melanoma, or SCC risk by body sites (data not shown).

Sensitivity analyses did not materially change the findings (data not shown).

Discussion

In our prospective study, tetracycline use was associated with modestly increased risk of BCC, but not with melanoma and SCC risk overall. Ambient UV radiation may interact with tetracycline use, increasing the risk of SCC.

Only limited studies have examined the associations between tetracycline use and risk of skin cancer. A Danish national register-based cohort study found a significant association between any short-term use of tetracycline and risk of melanoma (incidence rate ratio (IRR)=1.1, 95% CI=1.1–1.3), SCC (IRR=1.5, 95% CI=1.4–1.7), and BCC (IRR=1.3, 95% CI=1.3–1.4), but for long-term use of tetracycline (additional five courses of treatment with tetracycline), the association remained significant only for BCC (Kaae et al, 2010). A case–control study reported an increased risk of BCC (OR=1.8, 95% CI=1.2–2.8), but not SCC (OR=1.0, 95% CI=0.6–1.7), associated with ever tetracycline use (Robinson et al, 2013).

Previously, we have reported heterogeneous associations between UV radiation and risks of different skin cancers (Li et al, 2016). In the current study, risk of SCC with tetracycline use increased among those with higher UV exposure, and this may support our hypothesis that tetracycline, as a photosensitising medication, acts as a co-carcinogen with UV radiation. However, we did not find similar interactions by UV radiation for BCC, nor did we find significant interaction between sun-sensitive phenotypes and tetracycline use on any skin cancer risk. Whether the observed modestly increased risk of BCC is directly due to tetracycline’s phototoxic effects requires further investigation.

We observed much higher proportion of ever tetracycline users in NHS2 (45.0%) than NHS (4.9%) and HPFS (3.1%) (Table 1). Ever use of tetracycline was defined in NHS/HPFS as ‘use for at least two months’ and the majority of NHS/HPFS users may have used for acne or rosacea (Sutcliffe et al, 2007). Different from NHS/HPFS, NHS2 collected information on ‘ever use of tetracycline’ without specifying ‘at least two months’. Tetracycline came into commercial use in 1978, when NHS (age 30–55 years at cohort inception in 1976) and HPFS (40–75 years at cohort inception in 1986) participants were far beyond the adolescence for teenage acne. In addition, because of secular changes, the use of tetracycline has greatly increased. These may explain the observed high proportion of ever users in NHS2 (age 25–42 years at cohort inception in 1989). We collected diagnoses of acne/rosacea in NHS2 and diagnosis of periodontal disease in NHS/HPFS, although we did not specifically ask the diseases that tetracycline was used to treat for each individual. In one prior analysis of NHS2, severe teenage acne was associated with increased melanoma risk and decreased SCC risk, but was not associated with BCC (Zhang et al, 2015). In another study, rosacea was associated with increased BCC risk (Li et al, 2015) but we lack sound biological plausibility for the associations. Sensitivity analyses to address concern of confounding by indication (acne and rosacea in NHS2 and periodontal disease in NHS/HPFS) did not change our findings appreciably. Therefore, it is less likely that the observed associations can be directly explained by these diseases.

Our study has limitations. First, the cohorts did not assess use of other tetracycline class members. Therefore, we cannot assess use of other tetracycline family antibiotics, particularly doxycycline that has recognised photosensitising properties (Layton and Cunliffe, 1993; Drucker and Rosen, 2011). The above-mentioned Danish study reported significantly increased risk of melanoma, SCC, and BCC associated with doxycycline use (Kaae et al, 2010). However, a case–control study did not find significant associations with skin cancer (OR<1) (de Vries et al, 2012). Another tetracycline class drug, minocycline, is not considered photosensitising (Drucker and Rosen, 2011). Second, tetracycline use was only asked once and not updated during follow-up. This may have biased our effect estimates towards the null, as further exposure to tetracycline was not accounted for. We cannot assess whether skin cancers developed more frequently in tetracycline users with ongoing or repeated exposure. The different way of data collection on ever tetracycline use in three cohorts (NHS2 vs NHS/HPFS) is also a limitation of our study. Third, we cannot rule out residual confounding by aesthetic-related concerns; participants taking tetracycline antibiotics to treat visible skin diseases may be more likely to seek UV exposure for tanning purposes that would increase their risk of skin cancer.

In conclusion, ever tetracycline users had a modestly increased risk of BCC. Tetracycline use and higher UV exposure may jointly increase SCC risk. Although the effect tends to be at most modest, considering the common use of tetracycline antibiotics in clinical practice, our study supports further investigation on the potential skin cancer risk associated with tetracycline, particularly for prolonged periods of use and in individuals with high levels of UV exposure.

Change history

23 January 2018

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Colditz GA, Martin P, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Sampson L, Rosner B, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE (1986) Validation of questionnaire information on risk factors and disease outcomes in a prospective cohort study of women. Am J Epidemiol 123 (5): 894–900.

de Vries E, Trakatelli M, Kalabalikis D, Ferrandiz L, Ruiz-de-Casas A, Moreno-Ramirez D, Sotiriadis D, Ioannides D, Aquilina S, Apap C, Micallef R, Scerri L, Ulrich M, Pitkanen S, Saksela O, Altsitsiadis E, Hinrichs B, Magnoni C, Fiorentini C, Majewski S, Ranki A, Stockfleth E, Proby C EPIDERM Group (2012) Known and potential new risk factors for skin cancer in European populations: a multicentre case-control study. Br J Dermatol 167 (Suppl 2): 1–13.

Drucker AM, Rosen CF (2011) Drug-induced photosensitivity: culprit drugs, management and prevention. Drug Saf 34 (10): 821–837.

Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Willett WC, Speizer FE (1992) Diet and risk of basal cell carcinoma of the skin in a prospective cohort of women. Ann Epidemiol 2 (3): 231–239.

Kaae J, Boyd HA, Hansen AV, Wulf HC, Wohlfahrt J, Melbye M (2010) Photosensitizing medication use and risk of skin cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 19 (11): 2942–2949.

Layton AM, Cunliffe WJ (1993) Phototoxic eruptions due to doxycycline—a dose-related phenomenon. Clin Exp Dermatol 18 (5): 425–427.

Li WQ, Cho E, Weinstock MA, Mashfiq H, Qureshi AA (2016) Epidemiological assessments of skin outcomes in the Nurses' Health Studies. Am J Public Health 106 (9): 1677–1683.

Li WQ, Zhang M, Danby FW, Han J, Qureshi AA (2015) Personal history of rosacea and risk of incident cancer among women in the US. Br J Cancer 113 (3): 520–523.

Robinson SN, Zens MS, Perry AE, Spencer SK, Duell EJ, Karagas MR (2013) Photosensitizing agents and the risk of non-melanoma skin cancer: a population-based case-control study. J Invest Dermatol 133 (8): 1950–1955.

Stern RS (1998) Photocarcinogenicity of drugs. Toxicol Lett 102-103: 389–392.

Sutcliffe S, Giovannucci E, Isaacs WB, Willett WC, Platz EA (2007) Acne and risk of prostate cancer. Int J Cancer 121 (12): 2688–2692.

Zhang M, Qureshi AA, Fortner RT, Hankinson SE, Wei Q, Wang LE, Eliassen AH, Willett WC, Hunter DJ, Han J (2015) Teenage acne and cancer risk in US women: a prospective cohort study. Cancer 121 (10): 1681–1687.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and staff of the Nurses’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-up Study for their valuable contributions as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, and WY. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data. The views presented in this manuscript do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veteran Affairs. The work was supported by the Research Career Development Award of Dermatology Foundation, Richard B. Salomon Faculty Research Award of Brown University, the National Institute of Health Grants for Nurses’ Health Study (P01 CA87969 and UM1 CA186107), Nurses’ Health Study II (UM1 CA176726), and Health Professionals Follow-up Study (UM1 CA167552). The funding sources had no role in study design and conduct; in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the preparation, review, or approval of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author contributions

W-QL: study concept and design, statistical analysis, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, AMD: analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, EC: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, FL and TV: acquisition of data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, SL: statistical analysis and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, MAW: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, AAQ: study concept and design, acquisition of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, funding support, and study supervision.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

AAQ is a consultant for Abbvie, Amgen, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Li, WQ., Drucker, A., Cho, E. et al. Tetracycline use and risk of incident skin cancer: a prospective study. Br J Cancer 118, 294–298 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.378

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.378