Abstract

Data sources

To find studies to include in the review, searches were made using Biomed Central, Cochrane Oral Health Reviews, Cochrane Library, the Directory of Open Access Journals, PubMed, Science Direct and the Research Findings Electronic Register.

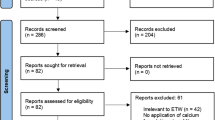

Study selection

English language clinical trials [randomised clinical trials (RCT) or quasi-RCT; in situ or in vivo] or systematic reviews (with or without meta-analysis) of published trials were selected that reported on the efficacy of phosphopeptide–amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP–ACP) using any mode of delivery. Studies were reviewed and their quality assessed independently.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data was extracted by two reviewers independently. Trials that were considered clinically and methodologically homogenous and that reported on similar outcomes were pooled for meta-analyses.

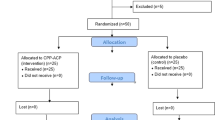

Results

Twelve articles were included of which five in-situ RCT could be pooled for meta-analyses. The pooled in-situ results showed a weighted mean difference (WMD) of the percentage remineralisation scores in favour of chewing gum with 18.8 mg CPP–ACP, compared with chewing gum without CPP–ACP of −8.01 [95% confidence interval (CI), −10.54– −5.48; P 0.00001], and compared with no intervention of −13.56 (95% CI, −16.49– −10.62; P 0.00001). A significantly higher remineralisation effect was also observed after exposure to 10.0 mg CPP–ACP (WMD, −7.75; 95% CI, −9.84– −5.66; P 0.00001). One long-term in vivo RCT (24 months) with a large sample size (N = 2720) found that the odds of a tooth surface's progressing to caries was 18% less in subjects who chewed sugar-free gum containing 54 mg CPP–ACP than in control subjects who chewed gum without CPP–ACP (P 0.03).

Conclusions

Within the limitations of this systematic review with meta-analysis, the results of the clinical in-situ trials indicate a short-term remineralisation effect of CPP–ACP. Additionally, the promising in-vivo RCT results suggest a caries-preventing effect for long-term clinical CPP–ACP use. Further RCT are needed in order to confirm these initial results in vivo.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

Reports of the effectiveness of CCP–ACP in caries prevention began to appear early in the decade, and have continued to appear over the years. A 2008 systematic review of essentially the same literature found the evidence insufficient to reach any conclusions regarding the effectiveness of CPP–ACP in vivo.1 Given the generally positive tone of the conclusion of the current review, it is instructive to consider why two reviews of the same literature came to dissimilar conclusions.

The authors of the current review take the earlier review1 to task for failing to meta-analyse the existing evidence, for expressing concern that the majority of the studies (six out of 10) were conducted by the same group of authors who patented the CPP–ACP complex, and for expressing concern that in-situ studies may not translate to clinical effectiveness. Their complaints are not necessarily well-founded, however. The authors of the 2008 systematic review1 did not indicate why they did not perform meta-analyses, but their evidence table highlights substantial differences in study characteristics. In fact, the statistically significant tests for heterogeneity in each of the current review's meta-analyses suggests that the analyses should be interpreted with caution. Also, the meta-analyses reported in the current review include only half of the available studies.

The current review includes eight out of the 10 caries prevention studies included in the 2008 review, and includes two new studies not available to the earlier review. Both of these two new studies were reported by the same group of authors associated with the patent. Thus, eight out of the 11 studies reviewed were performed by investigators with a conflict of interest. The current authors criticised the 2008 review, arguing that by noting this conflict an impression was created that the trials were biased. Yet, noting such conflict, so that readers are informed, is considered essential in assessments of systematic review quality.2

All but two of the included studies, and all of those meta-analysed, rely on an indirect, or surrogate measure of caries prevention, ie, the proportion of remineralisation in enamel slabs mounted in acrylic carriers. The strength of association between short-term measures of remineralisation in atypical clinical environments and reductions in caries lesions is unclear. Thus, it may be prudent to express caution when accepting differences in such surrogate measures as being indicative of clinical success.

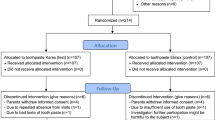

The important new evidence in the current review is the recent clinical trial examining the effect of CPP–ACE gum on approximal caries in adolescents.3 This report analyses 24-month transitions in radiographic density for these surfaces. The analyses show that the odds ratio of more demineralisation/ less remineralisation in the CPP–ACP groups than in the control gum group to be 0.82. But several aspects of the study should be noted. The dropout rate was high, at 33%. Detectable remineralisation was a relatively rare event in either group, with less than 1% of surfaces showing any evidence of remineralisation and about 6% showing demineralisation. Also, although visual, tactile decayed/ missing/ filled surfaces examinations were performed at baseline and study conclusion (24 months) they were not reported, with results based solely on the radiographic data.

This clinical trial,3 together with another small study of remineralisation of postorthodontic white-spot lesions represent the only direct clinical evidence of efficacy of CPP–ACP in caries prevention or remineralisation. The 2008 review noted that the study of white spots reported a significantly greater reduction in these lesions for CPP–ACP when the results were determined visually, but no difference when the outcome was assessed using laser fluorescence measures. The current review did not mention these conflicting results because laser detection methods were not an inclusion criterion.

The inescapable conclusion is that the two reviews reflect different levels of optimism, or acceptance of incomplete evidence. The 2008 review cautioned readers about apparent conflicts of interest and surrogate outcome measures, and declined to meta-analyse statistically heterogeneous study results. The current study discounted the conflict, was more willing to assume that the surrogate measure was a valid predictor of clinical performance, and was willing to risk synthesis of heterogeneous studies. The ‘truth’ in terms of certainty of the effectiveness of CPP–ACP in caries prevention probably lies between the conclusions of the two reviews. As always, let the reader beware.

Practice points

-

There is preliminary evidence that CPP–ACP can prevent caries, but until its effectiveness has been quantified, practitioners should not rely on it as a primary preventive method.

References

Azarpazhooh A, Limeback H . Clinical efficacy of casein derivatives: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Dent Assoc 2008; 139: 915–924.

Shea B, Grimshaw J, Wells G, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Method 2007; 7: 10.

Morgan M, Adams G, Bailey D, Tsao C, Fischman S, Reynolds E . The anticariogenic effect of sugar-free gum containing CPP–ACP nanocomplexes on approximal caries determined using digital bitewing radiography. Caries Res 2008; 42:171–184.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: S Mickenautsch, Division of Public Oral Health, University of the Witwatersrand, 7 York Road, Parktown/ Johannesburg 2193, South Africa. E-mail: neem@global.co.za

Yengopal V, Mickenautsch S. Caries preventive effect of casein phosphopeptide–amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP–ACP): a meta-analysis. Acta Odontol Scand 2009; 21: 1–12

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bader, J. Casein phosphopeptide–amorphous calcium phosphate shows promise for preventing caries. Evid Based Dent 11, 11–12 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400701

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400701

This article is cited by

-

Bleaching gel mixed with MI Paste Plus reduces penetration of H2O2 and damage to pulp tissue and maintains bleaching effectiveness

Clinical Oral Investigations (2020)

-

Micro-CT and FE-SEM enamel analyses of calcium-based agent application after bleaching

Clinical Oral Investigations (2018)