Credit: Mark Airs/Getty Images

Here’s how to deal with failure, say senior scientists

Don’t take it personally.

5 July 2019

Mark Airs/Getty Images

Rejection is a part of life. A career in academia makes this more apparent than perhaps any other career.

With success dependent on navigating tenure and grant applications while consistently publishing and achieving impact, it can feel as if you're scaling rungs on a ladder that break more often than they hold.

For a young academic whose path to early career researcher has been marked by success rather than failure, it can be a shock to the system.

So what happens when 'best and the brightest' are told “no”, over and over again?

Rejection in academia can feel personal, political, arbitrary and opaque. It can even feel – and sometimes is – discriminatory. But routine failure is built into the processes by which young academics progress. In order to survive, they need to learn how to overcome it.

It may help young academics to grow a thicker skin if their more experienced counterparts speak up to emphasise the normality of failure in the life of a successful researcher.

Risa Wechsler, professor of physics and Director of the Kavli Institute of Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology at Stanford University, did so to great effect this week:

Oh hey 17 year old self intimidated by overconfident dudes in freshman physics, oh hey anxious postdoc self sure none of it could possibly work out, oh hey super overwhelmed Assistant Prof self wondering how this job is possible: I became a Professor of Physics at Stanford today.

— Risa Wechsler (@RisaWechsler) July 2, 2019

As did Bryan W. Jones, retinal neuroscientist and director of the Marclab for Connectomics at the University of Utah, who tweeted this striking image of his grant successes and failures:

"Junior scientist struggling w/ grants asked for advice. I agreed to help them out, but also wanted them to see this image," Jones said.

"This image shows the grants that I’ve been involved with going back to 2012. The green dots are the successes, the red dots are failures. Keep submitting."

The tweet, which has so far garnered almost 7,000 likes and more than 2,000 retweets, sparked heated discussion among researchers, young and old, who knew the sting of rejection all too well:

Thanks for posting this. It is very difficult to convey this reality and that is partially because we don’t talk about our failure rate with specificity. You are maybe the fourth or fifth person I’ve seen put up their data.

— Drug Monkey (@drugmonkeyblog) June 26, 2019

Thank you for generously sharing this humble, illustrative and encouraging case of life as a researcher. This is exactly what my grant submission folders look like. Rejection is not failure. It’s all about probabilities. Good things come to those who work hard and never give up!

— Sigrid Carlsson (@SigridCarlsson) June 27, 2019

Some challenged the point that perseverance isn't all there is to it, which Jones acknowledged:

Survivor bias. So many drop out of the system because they cannot survive until (if at all) they get that next grant. So many aspects of privilege allow some to survive and thrive despite barriers while others don't due to their circumstance despite equal or even greater merit.

— Lee Constable (@Constababble) June 26, 2019

Jones joins a handful of researchers who have made an impact online by talking about their failures publically.

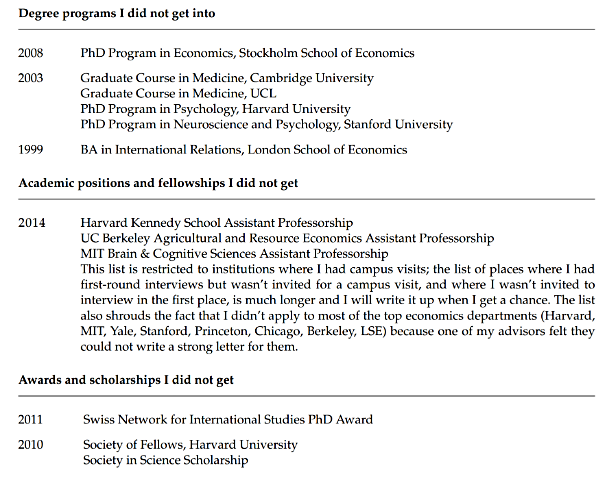

In 2016, Johannes Haushofer, professor of psychology and public affairs at Princeton, published his "CV of Failures".

See the full CV of Failures here.

Haushofer said he was inspired by a comment piece published by Nature in 2010 by Melanie I. Stefan, a biomedical sciences lecturer at the University of Edinburgh in the UK, who wrote that keeping a visible record of your rejected applications can help others to deal with setbacks.

Late last year, Robert Kelchen, assistant professor of higher education in the Department of Education Leadership Management and Policy at Seton Hall University in the US, put a percentage on his failures:

I just shared my spreadsheet of journal acceptances/rejections with a new graduate student. Students are always surprised to learn how high rejection rates are (mine is ~60%), and we as faculty need to model how to respond to rejection.

— Robert Kelchen (@rkelchen) December 5, 2018

"There is an old saying in baseball that even the best hitters fail 70% of the time, which shows the difficulty of hitting a round ball with a round bat," Kelchen wrote in an accompanying blog post.

"But while achieving a .300 batting average in baseball is becoming harder than it has been in decades, most academics would be overjoyed by a 30% success rate across all of their endeavours. This high failure rate often comes as a surprise for new graduate students, who only see the successes of faculty members and think that they never get rejected."

Kelchen's experience reflects the numbers.

The US National Institutes of Health states that its research project grant success rate increased from 18.7% in 2017 to 20.2% as of 30 September 2018.

In the UK, data provided to Times Higher Education by six research councils show that 25.8% of open-call funding applications were approved in 2017-18.

In Australia, the overall success rate for Discovery Projects for funding commencing in 2018 was 18.9%, according to the Australian Research Council.

For those who can’t accept the failure rates as they stand in academia, Philipp Kruger, who went from being a PhD student in immunology at the University of Oxford to a cell therapy medical manager at Novartis, says there’s no shame in transitioning to a different kind of career.

He adds that the scientific community could help to solve the problem of high rates of anxiety and depression among graduate students, “by encouraging us all to change the way we think about the PhD.”

“And scientists can start by appreciating a simple truth: researchers who leave academia are not failed academics," says Kruger.

Read next:

Scientists reveal their sacrifices for the sake of work