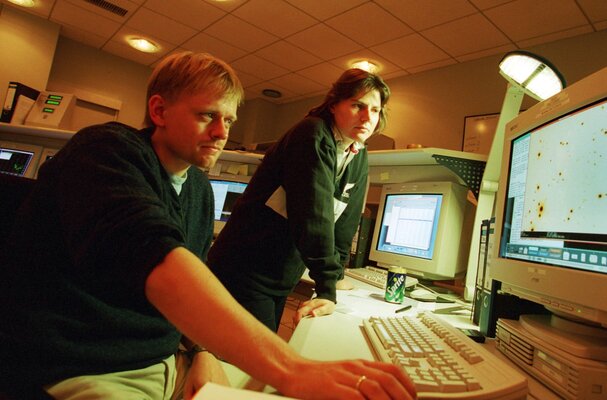

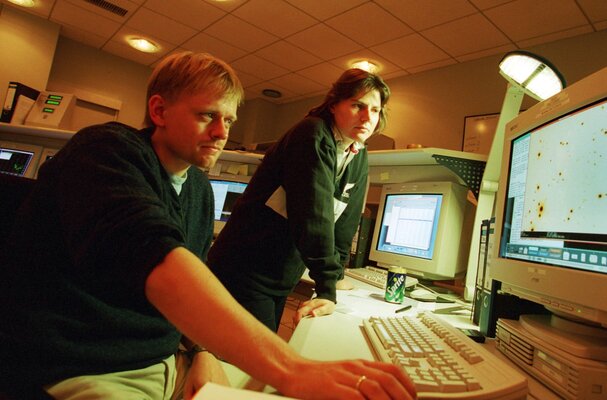

Astronomer Johan Fynbo (L), from Denmark, and Vanessa Doublier, from France, in the control centre of the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile. The European Southern Observatory, which runs operations of the VLT, has switched to double-blind peer reviews for equipment time applications.

Credit: Sven Creutzmann/Mambo Photo/Getty Images

Following NASA's lead, researchers are targeting gender bias in instrument time

The switch to double-blind peer reviews could help to ensure that female and early-career researchers get a fair shot at using in-demand equipment.

2 February 2021

Sven Creutzmann/Mambo Photo/Getty Images

Astronomer Johan Fynbo (L), from Denmark, and Vanessa Doublier, from France, in the control centre of the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile. The European Southern Observatory, which runs operations of the VLT, has switched to double-blind peer reviews for equipment time applications.

In 2019, NASA switched to double-blind peer reviews of applications for Hubble Space Telescope time after research showed that anonymising proposals practically equalized the chances of success between men and women. It marked a massive shift in review processes after years of apparent systemic gender bias in allocating scientific resources.

Now the initiative, first introduced by the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland, which runs operations for the Hubble and James Webb Space Telescope for NASA, is catching on at astronomy observatories, particle physics centres, and computing facilities in Europe, the United States, and Australia.

Researchers applying to use certain telescopes, synchrotrons, and supercomputers are now asked – and will be soon be required – to remove all investigator names and gender pronouns from their research proposals. Anonymous proposals also require applicants to remove any language that identifies previously published research as their own, to eliminate bias favouring well-established researchers.

The double-blind peer-review process, also known as dual-anonymisation, means reviewers don’t know who applicants are or what institute they are from, and vice versa.

Anonymising Hubble telescope proposals in this way reversed a 17-year trend of committees awarding telescope time to men more than women. Three years since the policy change at STScI, the gap between the success rates of women and men has shrunk from 6% to less than 1%.

It also dramatically increased the chances of first-time applicants being awarded telescope time, from only a handful each year to more than 50 new awardees in the last two allocation rounds, according the scheme’s chief architect, Lou Strolger, an observatory scientist at STScI.

Since 2020, the European Southern Observatory (ESO) and European Space Agency, with headquarters in Germany and France, respectively, and the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, have adopted dual-anonymous peer-review systems in an effort to reduce gender bias.

US agencies, including the National Science Foundation and US Department of Energy, which manages national laboratories, such as the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, are considering modifying their review processes.

A better result for science

When it comes to in-demand equipment, it’s the quality of the science that’s important, not the person who wrote the proposal, says Ferdinando Patat, head of ESO’s Observing Programmes Office, which administers the time allocation process for ESO facilities. It reviews some 1,800 proposals each year for two ground-based telescope facilities and the Atacama Pathfinder Experiment.

In adopting dual-anonymous reviews, Patat says ESO has largely followed the submission guidelines and panel review processes established by STScI for the Hubble telescope, with a few adjustments made along the way.

Most of the ESO community appears to be on board. In last year’s call for proposals, the first time ESO trialled dual-anonymous reviews, more than three-quarters of applicants voluntarily complied with the anonymisation guidelines. Anonymous applications will be mandatory for ESO’s next call for proposals in 2021.

“Ideally, by introducing this equality and fairness in the process, we also improve the quality of science,” says Patat.

In Australia, the Office of the Women in STEM Ambassador, led by astronomer Lisa Harvey-Smith, is also following NASA’s lead to replicate the STScI approach, and extending the initiative beyond space science to include other facilities.

The office is implementing a research program trialling double-blind reviews at four organizations that collectively receive around 1,670 research proposals each year. This includes Australia's Nuclear and Science Technology Organisation (ANSTO), which allocates time on its synchrotron and neutron-scattering facilities, and the National Computational Infrastructure (NCI), which manages four supercomputers.

Isabelle Kingsley, a research associate at the Office of the Women in STEM Ambassador, says the organizations are at various stages of implementing double-blind reviews. Application results across several allocation rounds will be compared to the three years prior to 2020.

The change should help women progress through to higher levels of research, where they are currently unrepresented, Kingsley says. If the results are as positive as the outcomes observed with the Hubble Space Telescope, their team will look at supporting other Australian research organizations in adopting double-blind peer reviews.

Mitra Safavi-Naeini, a physicist at ANSTO, submitted anonymous proposals in 2020 for the Australian Synchrotron and NCI’s supercomputers. She welcomes any procedure that separates bias from science, and allows reviewers to assess proposals in an objective way.

With proposals judged on their scientific merit alone, and not coloured by personal details or other factors, such as career stage or institution affiliation, the new system should also give women and early-career researchers more confidence to put forward their ideas, she says.