Non-academic staff, whose tasks can involve proposal preparation and writing, need more support.

Credit: skynesher/Getty Images

Calls for culture change as “them versus us” mindset drives rift between academic and non-academic staff

Research managers and administrators feel that their skills are underappreciated, survey reveals.

30 March 2021

skynesher/Getty Images

Non-academic staff, whose tasks can involve proposal preparation and writing, need more support.

An organization that represents research managers proposes action to tackle a “them versus us” culture after a survey of its members highlighted concerns that institutions do not value non-academic staff.

One former postdoctoral researcher who responded to the UK Association of Research Managers and Administrators’ (ARMA) survey said young researchers are “made to feel that they have failed” if they switch career paths to a professional services role. Another cited “discrimination against those who don’t have an academic background”.

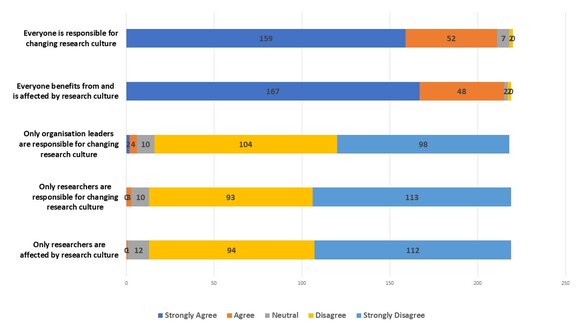

Overall, 281 respondents responded to the survey, which took place in September 2020, including 170 ARMA members, with 89% based in higher education, in roles that straddled project management, finance, IP commercialization, research governance and ethics, and marketing. Others worked in charity, government, healthcare and industry.

Most respondents described a supportive and collaborative workplace culture in their immediate team or department, but also a competitive one.

One research manager alluded to the unrealistic workload pressures faced by researcher colleagues as they grapple with the 2021 UK Research Excellence Framework (REF) quality assessment, open access requirements, and the need to demonstrate that their research has societal impact.

“This takes its toll on research culture overall,” the manager said.

Another comment described a culture that was “more focussed on winning funding rather than delivering research”. A third called for a culture in which everybody is recognized for their “different complementary strengths, not around a ‘star scientist’”.

Lack of recognition

ARMA’s survey report draws comparisons with UK funder Wellcome’s January 2020 global survey of more than 4,000 professionals involved in research, Reimagine Research Culture, particularly with respect to recognition of contributions.

For example, 26% of Wellcome respondents disagreed with the statement: “The work I do is fairly and adequately recognized.” Among ARMA respondents, 36% disagreed with a similar statement about their contributions being appropriately credited.

These similar results indicate “that those who work in the research ecosystem have shared experiences and more can be done to recognize the skills and creativity of RMAs [research managers and administrators] as compared to researchers,” ARMA’s report states.

One research manager talked of a colleague’s public engagement skills being “trumped” by academic colleagues with no prior experience of working with the public, adding: “For me, it’s an illustration that deference to academic expertise in all things is counterproductive.”

In its recommendations, ARMA calls for “parity of esteem” and a move away from the “them versus us” mindset between different roles, e.g. academics and administrators”, with increased shadowing opportunities between academics and RMAs.

Culture change

“This survey isn’t about RMAs moaning or to attribute blame. It’s about us opening up the conversation to see how we can work better together, to foster more mutual understanding and appreciation,” says Hilary Noone, who led the ARMA survey and is a faculty research and projects officer in humanities and social sciences at Newcastle University, UK.

“RMAs dedicate a lot of their time to improving the outcomes for researchers. We’re the oil to the cogs and love nothing more than seeing them have a positive experience.

“We really appreciate how academics struggle and the tensions and pressures on them. One reason I got involved in research culture in the first place is because I’ve seen firsthand the mental-health effects on researchers. The female academics who come to you and say they can’t have children because they are on a temporary contract, for example.”

Jennier Stergiou, who chairs ARMA, says it already works with many organizations to improve the research culture, including Wellcome, Universities UK, and UK Research and Innovation.

At a local level, she adds, research managers often feel valued by their line manager and immediate colleagues, but not always by the organization’s leadership and academic community. “Often the feeling is that they are just a bureaucracy to put hurdles in their way and make things difficult for them,” she says.

ARMA is also rolling out more professional skills training so its members can better communicate their role in fostering a healthy research culture at work.

“I can influence the research culture in my organization through conversations with the leadership,” says Stergiou, who is director of research and innovation services at Northumbria University, also in Newcastle.

“But the most junior research officer in the office is also influencing the culture in every conversation they have, and through the support they offer.”

Bjarne Bartlett et al.

Bjarne Bartlett et al.

Role of funders, publishers

ARMA’s survey report publication on March 22 coincides with a five-day virtual research culture festival, hosted by Wellcome.

“Funders have a big role to play in having policy responses which help to drive behaviour in organizations,” says Stergiou. “But research organizations shouldn’t need funders to put mechanisms in place to change those behaviours.”

Ben Bleasdale, a senior policy and advocacy advisor at Wellcome, described the “them versus us” highlighted in ARMA’s more targeted survey as a “worrying undercurrent”, alluding also to an often “adversarial environment” between the funding organization and research institutions.

“At times institutions feel like Wellcome is the kind of presence that you constantly have to be perfect for, so you lose that chance to have an honest conversation,” says Bleasdale.

“Wellcome needs to think carefully about how to rebuild that relationship. In the very competitive funding environment, there’s a sense of not being able to show any weakness to the funder.”

Bleasdale says Wellcome also supports the ARMA report’s recommendation for more organizations to adopt models which recognize the “invisible work of those who support research”.

One such model is CrediT, the Contributor Roles Taxonomy that straddles project administration, data curation, resources and software alongside writing, reviewing and editing.

“We hope to recognize the team effort more through the reforming of our grants,” says Bleasdale. “At the moment we take the Principal Investigator (PI) as the grant lead, the proxy for the team’s effort, which puts pressure on the PI to be everything to all people all the time and takes away their ability to point out the special skills in the team.”

The 22 publishers listed as adopters of CRediT on its website include Springer, which is part of Springer Nature, publisher of Nature Index. (Nature Index is editorially independent of its publisher).

A Springer Nature spokesperson said that although the taxonomy is not integrated into its systems, the company was involved in developing the CREdiT taxonomy and supports it. Nature and Nature journals have required authorship contribution statements since 1999 and some authors do use the taxonomy to write them. These statements are included in the author information sections of published papers.

Gemma Derrick, a higher education researcher at Lancaster University, UK and a specialist in evaluation systems in academia, says research managers require phenomenal diplomacy and advocacy skills to support the professional and pastoral needs of their researcher colleagues, alongside a broad range of technical skills.

“The ARMA survey shows how an overly stressful academic culture can affect those who are working with us. Research managers are a vital part of our culture and we have a duty of care to them,” says Derrick.

“Many academics often think these people are here to serve, but these are partners and colleagues who are more than aware of the stresses we face. Without them we would be in a mess.”