Abstract

Er3+ doped Y2O3 and Nb2O5 modified germanate glasses with different Er3+ concentrations were prepared. J-O intensity parameters were computed to estimate the structural changes due to the additions of Y2O3 and Nb2O5. The main mid-infrared spectroscopic features were investigated. To shed light on the observed mid-infrared radiative behavior, 975 nm and 1.53 μm emission spectra along with their decay lifetimes were also discussed. Moreover, the energy transfer processes of 4I11/2 and 4I13/2 level were quantitatively analyzed. In view of the experimental lifetimes, the simplified rate equation was utilized to calculate the energy transfer upconversion processes of upper and lower laser level of 2.7 μm emission. The theoretical calculations are in good agreement with the observed 2.7 μm fluorescence phenomena. Finally, the stimulated emission and gain cross sections were calculated and the results indicate that Er3+ doped germanate glasses have great potential for mid-infrared application.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, rare earth ions doped solid state lasers operating at mid-infrared (~3 μm) wavelength have attracted considerable interests. This is mainly due to the strong absorption band by water around this wavelength, which makes mid-infrared fiber lasers suitable for various applications including medical surgery, remote sensing and atmosphere pollution monitoring1,2,3,4. The merits of good beam quality, high conversion efficiency, power scalability and excellent heat dissipation promote fiber lasers greatly developed compared with bulk solid state lasers5. So far, mid-infrared fluoride glass fibers have been researched widely when doped with various rare earth ions such as Er3+, Ho3+ and Dy3+, etc6,7,8,9,10.

Because of the lack of commercially high-power pump diodes that can emit 1100 nm or 1300 nm wavelength energy, Ho3+ and Dy3+ doped fiber lasers have great difficulty in the realization of achievable output power. On the contrary, Er3+ doped fiber lasers are currently the most practical and convenient high power 3 μm laser, since the 980 nm or 808 nm absorption bands of Er3+ are readily excited by available high power AlGaAs and InGaAs laser diodes (LDs)11. In terms of this idea, in 2007, X. Zhu, et al. demonstrated the 2.78 μm laser emission with 9 W of output power as well as the slope efficiency of 21.3% when pumped at 975 nm from Er3+ doped ZBLAN fiber laser12. In 2009, S. Tokita, et al. reported 24 W of output power at 2.8 μm with slope efficiency of 14.5% using an Er3+ doped ZBLAN fiber13. However, the output power of 24 W was achieved in liquid-cooled condition owing to inferior thermal stability of the host13. Afterwards, higher output power has hardly been reported in Er3+ doped fluoride fiber lasers. Although fluoride glass fiber is the most efficient gain media for ~3 μm laser due to very low maximum phonon energy (~500 cm−1), its poor glass forming ability and troublesome fabrication process make it difficult for practical applications.

In order to solve the questions mentioned above and enhance output power of ~3 μm laser, search for a more appropriate glass host is urgent. Up to now, various glass hosts have been investigated for mid-infrared applications, including germanate, tellurite, bismuthate and fluorophoshate glasses14,15,16,17. Germanate glass, especially barium gallogermanate glass, has been of great interest due to the excellent combination of the infrared transparency, thermal stability, chemical durability and availability in large-size and complex shaping18. In addition, compared with silicate, borate or phosphate glasses, barium gallogermanate glass has a relatively low maximum phonon energy (800 ~ 900 cm−1). For Er3+ ions, the energy gap between 4I11/2 and 4I13/2 level is about 3700 cm−1. Thus, low phonon energy is beneficial for high radiative decay rate of Er3+: 4I11/2→ 4I13/2 transition and corresponding mid- infrared emission. However, some disadvantages hamper its further applications in the mid-infrared fields, such as high melting temperature, high viscosity and a large amount of hydroxyl groups19. To address the questions, fluorides involving BaF2 and LiF have been added into germanate glass so as to reduce the concentration of hydroxyl groups as well as lowering glass melting temperature for energy conservation19. At the same time, it has been demonstrated that the Y2O3 and Nb2O5 additions can be used to modify the properties of barium gallogermanate glass20,21. The addition of Y2O3 component is expected to improve thermal stability and reduce OH− content in glass due to its collection of non-bridging oxygen of glass, while Nb2O5 is expected to enhance radiative transition probability and emission cross section for mid-infrared emission due to its high refractive index21.

Hence, Y2O3 and Nb2O5 modified germanate glasses were prepared and mid- infrared spectroscopic properties were investigated in present work. In general, the long lifetime of the lower laser level 4I13/2 level compared with the upper level of 4I11/2 level leads a population bottleneck. Thus, it limits the CW laser transition and output power. Fortunately, the population bottleneck problem in Er3+ doped laser systems have been overcome effectively to improve corresponding mid-infrared emission and it can be explained by energy transfer upconversion (ETU) process between two Er3+ ions5. Moreover, the ETU: 4I13/2+ 4I13/2→ 4I15/2+ 4I9/2 process can lead to a fast depletion of the lower laser level and the realization of CW operation as well as recycling of the energy. However, only qualitative analysis on enhanced mid-infrared emission has been carried out, up to now. Hence, energy transfer processes of Er3+: 4I11/2 and 4I13/2 level have been analyzed quantitatively in this work. According to the measured lifetimes, the energy transfer upconversion processes of upper and lower level of 2.7 μm emission were calculated based on the simplified rate equation model so as to elucidate the observed mid-infrared radiative behavior.

Experimental

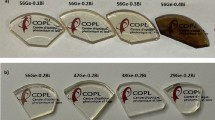

The investigated samples have the following molar compositions in mol%: 62GeO2-9Ga2O3-13BaF2-7Y2O3(Nb2O5)-9LiF-xEr2O3, denoted as YxEr and NxEr, respectively (x = 1, 2, 3). Batches of 20 g samples were well-mixed and melted in aluminum crucibles at 1400°C for 45 min. Then melts were cast on a preheated steel plate and annealed for several hours around the glass transition temperature. All the annealed samples were fabricated and polished to the size of 10 mm × 10 mm × 1.5 mm for the optical property measurements.

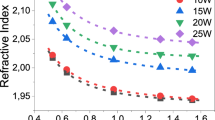

The characteristic temperatures (temperatures of glass transition Tg, onset crystallization peak Tx and top crystallization peak Tp) of prepared samples were characterized using a Netzsch STA 449/C differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) at a heating rate of 10 K min−1. The densities and refractive indexes of samples were tested by the Archimedes method and the prism minimum deviation method, respectively. Furthermore, absorption spectra were recorded with a Perkin-Elmer Lambda 900 UV/VIS/NIR spectrophotometer in the range of 360–1700 nm. The emission spectra (950–1025 nm, 1400–1700 nm and 2550–2800 nm) were measured via a Triax 320 type spectrometer upon excitation of 808 nm. Besides, the decay curves of 975 nm and 1530 nm were determined by light pulses of the 808 nm LD and HP546800B 100-MHz oscilloscope. All the measurements were carried out at room temperature.

Results and discussion

Thermal stability

Fig. 1 shows the measured DSC curves of present samples. In order to analyze the effect of Er2O3 content on the thermal property, Table 1 lists the characteristic temperatures such as temperatures of glass transition (Tg), onset crystallization (Tx) and peak crystallization (Tp) as well as the calculated thermal stability parameters ΔT and S in present work. For comparison, other values reported are also tabulated in Table 1. For YxEr sample, the characteristic temperatures have no evident changes with the increase of Er2O3 content whereas the increment of Er2O3 concentration leads to the enhanced characteristic temperatures for NxEr sample. In addition, the Tg, Tx and Tp of Y1Er sample are higher than those of N1Er sample along with the same tendency of other concentrations. On the other hand, the ΔT, which is defined as Tx-Tg, of all present samples is similar, about 135°C. It is much higher than those of fluorophosphate and MgO/Al2O3/SiO2/TiO2 system, as shown in Table 1. It is noted that the Tg of Y2O3 modified sample is much higher than those of fluorophosphate and NxEr glasses while lower than that of MgO/Al2O3/SiO2/TiO2 system22. The reason that YxEr sample has higher glass transition temperature compared with NxEr sample may be ascribe to the fact that Y2O3 in YxEr sample can collect glass network and strengthen the structure of the network21.

The parameter S is more accurate to estimate the glass stability, which reflects the resistance to devitrification after the formation of the glass and can be defined by22

where (Tp-Tx) is related to the rate of devitrification transformation of the glassy phases. On the other hand, the high value of ΔT delays the nucleation process. It can be observed from Table 1 that the S values in present samples are both larger than those of fluorophosphate glass and MgO/Al2O3/SiO2/TiO2 system22,23. It is indicated that excellent thermal stability can be achieved from the prepared glasses, which is greatly beneficial to optical fiber drawing. It is worth mentioned that the S of NxEr sample is larger than that of YxEr sample, indicating that anti-crystallization ability for Nb2O5 modified germanate glass is superior than that of Y2O3 modified one. This phenomenon might be explained by the fact that field strength of Nb5+ ion is higher than that of Y3+ ion and higher field strength can restrain the crystallization behavior of glass21.

Absorption spectra and J-O analysis

Fig. 2 displays the absorption spectra in Er3+ doped germanate glasses. Ten absorption bands corresponding to the ground state 4I15/2 to other higher levels are labeled in this figure. For YxEr series, absorption intensity is proportional to the Er3+ concentration as is the same with NxEr samples. In order to compare the difference of YxEr and NxEr, the inset (a) of Fig. 2 shows the absorption spectra of Y3Er and N3Er sample. It is observed that similar shape and peak positions occur in various glasses. It is also similar to other reported glasses16,24. Minor divergence can be found from absorption spectra for different glasses and can be devoted to the various strengths of ligand fields. It is noted that two very sharp peaks corresponding to the transitions of 4I15/2→ 4G11/2 and 4I15/2→ 2H11/2 are evident, which is designated as hypersensitive transitions (HSTs)25. They are sensitive to the local environment around rare earth ions. The intensity divergence between YxEr and NxEr results from the different composition of the germanate glasses and the changes in Er3+ surrounding local environment.

The solubility of rare earth ions can be estimated roughly by the variation of the absorption intensities with Er3+ concentration. Variation of integral absorption intensities of the 4I15/2→ 4I13/2 transition as a function of Er3+ content is presented in the inset (b) of Fig. 2. It shows good linearity for YxEr and NxEr, which means excellent solubility of rare earth ions for the current melting scheme in both series. Additionally, it is observed from Fig. 2 that an absorption band around 800 nm is obvious, suggesting that Er3+ doped germanate glasses can be pumped by commercially available and low-cost 808 nm LD.

According to Judd-Ofelt (J-O) theory26,27, the magnitude of the measured and calculated oscillator strengths can be determined as well as some important spectroscopic parameters of trivalent rare earths doped glasses. Details of the theory and method have been well described earlier28,29. Hence only results are presented here. The experimental oscillator strengths of Er3+ in germanate glasses are listed in Table 2 and compared with other results reported. It can be seen from Table 2 that the measured oscillator strengths in present work are higher than those of Er3+ doped silicate and fluoride glasses30,31 but lower than those of Er3+ doped tellurite glass32. This behavior is in good agreement with the instinct rule of environment in glasses surrounding the rare-earth ions. It is worth noting that the oscillator strength corresponding to Er3+: 4I15/2→ 2H11/2 (HST) is much higher than those of other transitions for all glass systems. Moreover, it is interesting to note that the oscillator strength of the HST shows great changes in different glasses, which results from the different ligand environment in the vicinity of Er3+ ions. In addition, the N2Er possesses larger oscillator strengths in comparison with Y2Er, suggesting the additions of Nb2O5 and Y2O3 have substantial influence on the local ligand around Er3+ ions.

To further investigate the effects of Nb2O5 and Y2O3 on the local environment of glasses, the J-O parameters Ωλ (λ = 2,4,6) of Er3+ in present work have been determined and shown in Table 3. At the same time, the values of other glass systems doped with Er3+ are also listed in Table 3 for comparison. The root mean square deviation (δr.m.s) between the calculated (fexp) and experimental (fcal) oscillator strengths can be as low as 0.14 × 10−6 and 0.15 × 10−6, respectively, for N2Er and Y2Er as revealed in Table 3, indicating that the calculation process is reliable. According to Jϕrgensen and Reisfeld33, Ω2 is strongly affected by covalency and Ω6 is closely related to the rigidity of glass host. As is shown in Table 3, the obtained Ω2 values in this work are both higher than those of fluorophosphate, bismuthate and fluoride glasses17,24,34 and comparable to that of other germanate glass35. This behavior is derived from the more covalent nature of germanate glass. It is reported by Tanabe et al that Ω6 increases with the drop of local basicity in the ligands36,37,38. The present glasses possess higher Ω6 compared with bismuthate and germanate glasses and it is slightly lower than those of fluorophosphate and fluoride glasses, indicating the lower local basicity of present germanate glasses. Furthermore, the Ω2 of N2Er is larger than that of Y2Er, while the Ω6 between them is similar. It is suggested that higher covalency in N2Er can be determined in comparison with Y2Er. It might be ascribed to the fact that the covalency of Nb-O bond is stronger than that of Y-O bond and the effect of Nb-O bond on the local ligand field around Er3+ is larger than that of Y-O bond21.

Some important radiative parameters can be calculated by using the intensity parameters Ωλ to estimate the potential mid-infrared emission performance. The detailed procedure has been well described earlier29. Table 4 displays the spontaneous radiative transition probability (Arad), branching ratios (β) and radiative lifetimes (τrad) of Er3+ for selected level transition in germanate glasses. The results show that the Arad for Er3+: 4I11/2→ 4I13/2 transition in Y2Er and N2Er samples can be as high as 30.24 and 35.12 s−1, respectively, both are higher than those of ZBLAY (26.10 s−1)25 and ZBLA (19 s−1)39. High radiative transition probability provides a better opportunity to achieve 2.7 μm fluorescence from Er3+: 4I11/2→ 4I13/2 transition.

Fluorescence spectra

To investigate the effect of additions of Y2O3 and Nb2O5 on the mid-infrared emission properties in Er3+ doped germanate glasses, the 2.7 μm fluorescence spectra of Y2Er and N2Er, as an example, were measured upon the excitation of 808 nm LD and revealed in Fig. 3(a). It can be seen that one emission peak centered at 2.7 μm occurs, which corresponds to the Er3+: 4I11/2→ 4I13/2 transition. Besides, the emission intensity of Y2Er is evidently stronger than that of N2Er. It is indicated that Y2O3 modified germanate glass is more suitable for mid-infrared material. Subsequently, the mid-infrared emission spectra of Y2O3 modified germanate glass with different Er3+ concentrations were determined, as shown in Fig. 3(b). It is found that the intensity of 2.7 μm fluorescence increases with increasing Er2O3 concentration and no luminescence quenching happens.

To clearly elucidate the 2.7 μm emission phenomenon, the 975 nm and 1.53 μm fluorescence spectra were tested by 808 nm LD pumping, as shown in Fig. 3(c), (d), (e) and (f). Furthermore, the simplified energy level diagram and energy transfer mechanism of Er3+ is given in Fig. 4 so as to readily comprehend the relation of 2.7 μm, 975 nm and 1.53 μm emissions. As is shown in Fig. 4, when the sample is radiated by 808 nm LD, the ions in ground state 4I15/2 are excited to the 4I9/2 level. Due to the small energy gap between 4I9/2 and 4I11/2 level, ions of 4I9/2 level relax non-radiatively to the next 4I11/2 level and then the 975 nm and 2.7 μm radiations take place according to the 4I11/2→ 4I15/2 and 4I11/2→ 4I13/2 transitions, respectively. Finally, the ions in 4I13/2 level decay radiatively to the ground state and the 1.53 μm emission occurs. According to Fig. 3(c), the 975 nm emission of Y2Er is weaker than that of N2Er. It might be attributed to the divergence of local environment surrounding Er3+ ions and leading to different fluorescent behaviors between Y2Er and N2Er. Decay curves will be determined to further elucidate the divergence of fluorescent behavior in next section. It means that more ions in 4I11/2 level have undergone the 4I11/2→ 4I13/2 transition for Y2Er compared with N2Er. Hence, the 2.7 μm emission intensity of Y2Er is higher than that of N2Er. In addition, it can be obtained from Fig. 3(d) that the intensity of 1.53 μm emission for Y2Er is slightly higher than that of N2Er, which is in good agreement with the behavior of 2.7 μm fluorescence.

Furthermore, the 975 nm and 1.53 μm fluorescence spectra of YxEr samples doped with different Er3+ concentrations were determined and given in Fig. 3(e) and (f). It is found that the 975 nm and 1.53 μm fluorescence intensities increase with the increment of Er3+ content. They are in good accordance with the behavior of 2.7 μm fluorescence. However, they can not be used to comprehend the origin of 2.7 μm emission behavior. Hence, more comprehensive discussions will be carried out to understand the mid-infrared fluorescence behavior in the next section.

Decay curves, energy transfer evaluation and rate equation analysis

Fluorescence lifetime is an important parameter to estimate the ions behavior of the excited state. Higher lifetime is indicative of slower ions decay and is beneficial for population accumulation. Fig. 5 (a) and (b) signifies the decay curves of 975 nm and 1.53 μm emissions in Y2Er and N2Er by 808 nm LD pumping. According to the measured decay curves, the fluorescence lifetime can be determined by the time of the intensity of 1/e. From Fig. 5(a), it can be found that the 4I11/2 level lifetime of Y2Er is longer than that of N2Er while the 4I13/2 level lifetimes between Y2Er and N2Er are similar as shown in Fig. 5(b). It is suggested that the upper level of 2.7 μm emission for Y2Er is more favorable for ions accumulation and Y2Er is more helpful for population inversion between 4I11/2 and 4I13/2 level compared with N2Er. Hence, the more intense 2.7 μm radiation can be observed from Y2O3 modified germanate glass as demonstrated in Fig. 3(a).

Fig. 5(c) and (d) shows the decay curves of 975 nm and 1.53 μm emissions in YxEr samples with various Er3+ concentration excited by 808 nm LD. It is expected to elucidate the origin of enhanced 2.7 μm emission with Er3+ concentration. From Fig. 5 (c) and (d), it is observed that the 975 nm lifetime increases basically from 192 to 239 μs, whereas the 1.53 μm lifetime reduces from 7.16 to 3.31 ms. Thus, ions in 4I11/2 level can be accumulated effectively and ions in 4I13/2 level can be greatly reduced. Hence, population inversion corresponding to 2.7 μm emission is easier to achieve with increasing Er3+. Therefore, 2.7 μm emission intensity increases with the increment of Er3+ in present work.

Energy transfer coefficient is another important parameter to affect 2.7 μm fluorescence characteristics. As is shown in Fig. 6, in order to obtain excellent mid-infrared emission, it is necessary to weaken the ET1 and strengthen ET2 process. To verify the Y2Er is more superior for mid-infrared material compared with N2Er, energy transfer coefficients of both glasses were calculated and analyzed. The energy transfer processes ET1 and ET2 can be evaluated by the calculation of the absorption and emission cross sections. The extended overlap integral method is extensively utilized to investigate energy transfer processes between donor and acceptor. For a dipole-dipole interaction, the microscopic energy transfer probability between donor (D) and acceptor (A) ions can be denoted as40

where R is the distance between donor and acceptor, the CD-A is the energy transfer constant that can be expressed as follows41

where RC is the critical radius of the interaction and τD is the intrinsic lifetime of the donor excited level. When phonons participate in the considered process, the energy transfer coefficient (CD-A) can be determined by the following equation40,41

where c is the light speed, n is the refractive index,  and

and  is the degeneracy of the lower and upper levels of the donor, respectively.

is the degeneracy of the lower and upper levels of the donor, respectively.  is the maximum phonon energy,

is the maximum phonon energy,  is the average occupancy of the phonon mode at the temperature of T. m is the number of the phonons that participate in the energy transfer. S0 is the Huang-Rhys factor and

is the average occupancy of the phonon mode at the temperature of T. m is the number of the phonons that participate in the energy transfer. S0 is the Huang-Rhys factor and  is the wavelength with m phonon creation.

is the wavelength with m phonon creation.

In this work, the donor and acceptor both are Er3+ ions. For the purpose of obtaining the CD-A values of ET1 and ET2 processes, firstly the absorption and emission cross sections at 975 nm and 1.53 μm need to be calculated.

The absorption cross section (σabs) is defined as

where OD(λ), N, l represent the optical density which is obtained from absorption spectra, Er3+ doping concentration in this paper and sample thickness, respectively. The stimulated emission cross-section (σem) is calculated according to the McCumber theory42 as follows

where Zl and Zu are partition functions of the lower and upper manifolds, respectively. ε is the net free energy demanded to excite one Er3+ from the 4I15/2 to the excited state at the temperature of T.

According to equation (5) and (6), the absorption and emission cross sections were determined and displayed in Fig. 6 (a) and (b). Further, the energy transfer coefficients of ET1 and ET2 processes were computed by equation (4) and they are listed in Table 5. The results indicate that the energy transfer ET1 and ET2 processes in Y2Er and N2Er glasses scarcely need phonon assistance. From Fig. 6, we observe overlap to a large extent between absorption and emission cross sections at 975 nm and 1.53 μm. Thereby, ET1 and ET2 processes mainly undergo resonant energy transfer and scarcely phonon assistance is needed. For ET1 process, the energy transfer coefficient (CD-A) of Y2Er is dramatically lower than that of N2Er while the CD-A of Y2Er is slightly smaller than that of N2Er for ET2 process. Smaller energy transfer coefficient of 4I11/2 level and larger CD-A of 4I13/2 state indicate that Y2Er is more beneficial for population inversion and more efficient 2.7 μm emission can be achieved compared with N2Er.

For YxEr glass system, the mid-infrared intensity increases with increased Er3+ concentration. To explain the behavior, the rate equation model is proposed and the simplified rate equation is given as follows43

where CETU is energy transfer upconversion coefficient. Assuming that when the pumping source is turned off, feeding from higher level to lower level 1 and 2 becomes negligible as shown in Fig. 6. The decaying behavior is mainly governed by the steady-state populations. By solving this simplified rate equation, the formula can be obtained as

where N0 is the steady-state population of level 1 and 2 immediately before switch-off. A plot of (N0/Nt)exp(-t/τ) vs. (1 - exp(-t/τ)) will give a slope k, which is denoted as

Fig. 7 (a) and (b) indicate the plots of (N0/Nt)exp(-t/τ) vs. (1 - exp(-t/τ)) for 975 nm and 1.53 μm decay data, respectively. By linear fitting of the data of Fig. 7, the slope values can be determined and tabulated in the inset of Fig. 7 (a) and (b), respectively. Finally, the energy transfer upconversion coefficient can be obtained using equation (9). Fig. 8 gives the dependence of energy transfer upconversion (ETU) coefficient on the Er3+ concentration for 4I11/2 and 4I13/2 level.

From Fig. 8, it can be clearly seen that the CETU value substantially reduces with increasing Er3+ concentration for 4I11/2 level. Lower CETU means that more ions can be accumulated in 4I11/2 level, which can enhance the 2.7 μm emission. In parallel, the CETU of 4I13/2 level increases on the whole with Er3+ concentration, which is helpful to decrease the ions of 4I13/2 level by transferring energy to adjacent level. Thus, population inversion between the 4I11/2 and 4I13/2 level is greatly improved and the 2.7 μm fluorescence is enhanced with increasing Er3+ concentration.

Absorption, emission and gain cross sections at 2.7 μm

On the basis of discussions above, it can be concluded that Y3Er sample possesses optimal fluorescence characteristics. Therefore, by selecting the Y3Er, the absorption, emission and gain cross sections were calculated to further estimate its possibility as mid-infrared laser material. The stimulated emission cross section (σem) of 2.7 μm fluorescence can be determined by Füchtbauer-Ladenburg equation44

where Arad is the spontaneous transition probability, I(λ) is the fluorescence spectra intensity. Combining equation (10) and (6), the absorption (σabs) and emission cross sections (σem) at 2.7 μm in Y3Er have been calculated and displayed in Fig. 9(a). It can been seen that the peak absorption and emission cross sections can reach to 10.6 × 10−21 cm2 and 12.4 × 10−21 cm2, respectively. It is reported that high emission cross section is extremely useful to determine the possibility to achieve laser effect25. The σem of present work is much higher than those of bismuth germanate glass (6.61 × 10−21 cm2)45, fluoride glass (9.16 × 10−21 cm2)24 and other germante glass (7.02 × 10−21 cm2)46. Moreover, The value of σem is also larger than that of ZBLAN (9.5 × 10−21 cm2)4, from which the 2.7 μm laser output has been achieved so far12,13. It is expected that 2.7 μm laser emission can also be obtained from the prepared germanate glass. Hence, the investigated germanate glass has potential advantages for mid-infrared applications.

Besides, the gain cross section (G) was calculated derived from σabs and σem to evaluate the mid-infrared gain properties. The room temperature gain cross section can be simply evaluated by47

where P is the population inversion given by the ratio between the population of Er3+: 4I11/2 level and the total Er3+ concentration. Fig. 9(b) shows the gain cross sections of Y3Er sample. It is found that the gain becomes positive when P is more than 0.4, which is similar to the case of ZBLAN3. It is indicated that a low pumping threshold can be achieved for the 2.7 μm in prepared glass.

Conclusions

Er3+ doped germanate glass with additions of Y2O3 and Nb2O5 and different Er3+ concentrations were prepared. Their main mid-infrared spectroscopic properties were evaluated. To elucidate clearly the mid-infrared emission behavior, the 975 nm and 1.53 μm emission spectra, their decay curves were tested and analyzed. Moreover, the energy transfer processes of 4I11/2 and 4I13/2 level have been quantitatively calculated and discussed. Based on the lifetime measurement, the simplified rate equation was used to determine the energy transfer upconversion coefficients of the upper and lower levels of 2.7 μm emission. The theoretical calculations coincide well with the observed phenomena. Furthermore, the prepared germanate glasses possess high stimulated emission cross section (12.4 × 10−21 cm2) and a low pumping threshold, which might have potential application in mid-infrared laser.

References

Seddon, A. B., Tang, Z., Furniss, D., Sujecki, S. & Benson, T. M. Progress in rare-earth-doped mid-infrared fiber lasers. Opt. Express 18, 26704–26719 (2010).

Zhou, P., Wang, X., Ma, Y., Lü, H. & Liu, Z. Review on recent progress on mid-infrared fiber lasers. Laser Phys. 22, 1744–1751 (2012).

Wu, B. et al. Fiber laser-pumped, chirped, PPMgLN-based high efficient broadband mid-IR generation. Chin. Opt. Lett. 11, 081901 (2013).

Huang, F. et al. 2.7 mum emission of high thermally and chemically durable glasses based on AlF3. Sci. Rep. 4, 3607 (2014).

Li, J. F. & Jackson, S. D. Theoretical study and optimization of a high power mid-infrared erbium-doped ZBLAN fibre laser. Chin. Phys. B 20, 034205 (2011).

Jackson, S. D., Pollnau, M. & Li, J. Diode pumped erbium cascade fiber lasers. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 47, 471–478 (2011).

Chai, G., Dong, G., Qiu, J., Zhang, Q. & Yang, Z. Phase transformation and intense 2.7 um emission from Er3+ doped YF3/YOF submicron-crystals. Sci. Rep. 3, 1598 (2013).

Hu, T., Hudson, D. D. & Jackson, S. D. Actively Q-switched 2.9 μm Ho3+/Pr3+-doped fluoride fiber laser. Opt. Lett. 37, 2145–2147 (2012).

Tsang, Y. H., El-Taher, A. E., King, T. A. & Jackson, S. D. Efficient 2.96 µm dysprosium-doped fluoride fibre laser pumped with a Nd:YAG laser operating at 1.3 µm. Opt. Express 14, 678–685 (2006).

Hudson, D. D., Williams, R. J., Withford, M. J. & Jackson, S. D. Single - frequency fiber laser operating at 2.9 μm. Opt Lett 38, 2388–2390 (2013).

Wu, J. et al. Efficient thulium-doped 2-μm germanate fiber laser. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 18, 334–336 (2006).

Zhu, X. & Jain, R. 10W level diode-pumped compact 2.78 μm ZBLAN fiber laser. Opt. Lett. 32, 26–28 (2007).

Tokita, S., Murakami, M., Shimizu, S., Hashida, M. & Sakabe, S. Liquid-cooled 24 W mid-infrared Er: ZBLAN fiber laser. Opt. Lett. 34, 3062–3064 (2009).

Bai, G., Tao, L., Li, K., Hu, L. & Tsang, Y. H. Enhanced light emission near 2.7 μm from Er–Nd co-doped germanate glass. Opt. Mater. 35, 1247–1250 (2013).

Gomes, L., Lousteau, J., Milanese, D., Mura, E. & Jackson, S. D. Spectroscopy of mid-infrared (2.9 μm) fluorescence and energy transfer in Dy3+-doped tellurite glasses. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B: Opt. Phys. 31, 429–435 (2014).

Guo, Y., Li, M., Hu, L. & Zhang, J. Intense 2.7 µm emission and structural origin in Er3+- doped bismuthate (Bi2O3-GeO2-Ga2O3-Na2O) glass. Opt. Lett. 37, 268 (2012).

Zhang, L., Yang, Z., Tian, Y., Zhang, J. & Hu, L. Comparative investigation on the 2.7 μm emission in Er3+/Ho3+ codoped fluorophosphate glass. J. Appl. Phys. 110, 093106 (2011).

Tang, B., Yang, Y., Fan, Y. & Zhang, L. Barium gallogermanate glass ceramics for infrared applications. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 26, 558–563 (2010).

Cao, G., Lin, F., Hu, H. & Gan, F. A new fluorogermanate glass. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 326–327, 170–176 (2003).

Jewell, J. M., Higby, P. L. & Aggarwal, I. D. Properties of BaO - R2O3 - Ga2O3 - GeO2 (R = Y, Al, La and Gd) Glasses. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 77, 697–700 (1994).

Wei, T., Chen, F., Tian, Y. & Xu, S. Efficient 2.7 μm emission and energy transfer mechanism in Er3+ doped Y2O3 and Nb2O5 modified germanate glasses. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transfer 133, 663–669 (2014).

Goel, A., Shaaban, E. R., Melo, F. C. L., Ribeiro, M. J. & Ferreira, J. M. F. Non-isothermal crystallization kinetic studies on MgO–Al2O3–SiO2–TiO2 glass. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 353, 2383–2391 (2007).

Liao, M., Sun, H., Wen, L., Fang, Y. & Hu, L. Effect of alkali and alkaline earth fluoride introduction on thermal stability and structure of fluorophosphate glasses. Mater. Chem. Phys. 98, 154–158 (2006).

Tian, Y., Xu, R., Hu, L. & Zhang, J. Spectroscopic properties and energy transfer process in Er3+ doped ZrF4-based fluoride glass for 2.7 μm laser materials. Opt. Mater. 34, 308–312 (2011).

Tian, Y., Xu, R., Hu, L. & Zhang, J. 2.7 μm fluorescence radiative dynamics and energy transfer between Er3+ and Tm3+ ions in fluoride glass under 800nm and 980nm excitation. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transfer 113, 87–95 (2012).

Judd, B. Optical Absorption Intensities of Rare-Earth Ions. Phys. Rev. 127, 750–761 (1962).

Ofelt, G. S. Intensities of Crystal Spectra of Rare-Earth Ions. J. Chem. Phys. 37, 511 (1962).

Shojiya, M., Kawamoto, Y. & Kadono, K. Judd-Ofelt parameters and multiphonon relaxation of Ho3+ ions in ZnCl2-based glass. J. Appl. Phys. 89, 4944 (2001).

Xu, R., Tian, Y., Hu, L. & Zhang, J. Origin of 2.7 μm luminescence and energy transfer process of Er3+: 4I11/2→4I13/2 transition in Er3+/Yb3+ doped germanate glasses. J. Appl. Phys. 111, 033524 (2012).

Pisarski, W. A. Spectroscopic analysis of praseodymium and erbium ions in heavy metal fluoride and oxide glasses. J. Mol. Struct. 744–747, 473–479 (2005).

Qiao, X., Fan, X., Wang, M. & Zhang, X. Up-conversion luminescence and near infrared luminescence of Er3+ in transparent oxyfluoride glass-ceramics. Opt. Mater. 27, 597–603 (2004).

Joshi, P., Shen, S. & Jha, A. Er3+-doped boro-tellurite glass for optical amplification in the 1530-1580nm. J. Appl. Phys. 103, 083543 (2008).

Jørgensen, C. K. & Reisfeld, R. Judd-Ofelt parameters and chemical bonding. Journal of the Less Common Metals 93, 107–112 (1983).

Zhao, G., Kuan, P. W., Fan, H. & Hu, L. Enhanced green and red upconversion and 2.7 μm emission from Er3+/Tm3+ co-doped bismuth germanate glass. Opt. Mater. 35, 910–914 (2013).

Ajroud, M. et al. Energy transfer processes in (Er3+-Yb3+)-codoped germanate glasses for mid-infrared and up-conversion applications. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 26, 523–529 (2006).

Tanabe, S., Yoshii, S., Hirao, K. & Soga, N. Upconversion properties, multiphonon relaxation and local environment of rare-earth ions in fluorophosphate glasses. Phys. Rev. B 45, 4620–4625 (1992).

Tanabe, S., Takahara, K., Takahashi, M. & Kawamoto, Y. Spectroscopic studies of radiative transitions and upconversion characteristics of Er3+ ions in simple pseudoternary fluoride glasses MFn–BaF2–YF3 (M: Zr, Hf, Al, Sc, Ga, In, or Zn). J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 12, 786–793 (1995).

Tanabe, S., Ohyagi, T., Todoroki, S., Hanada, T. & Soga, N. Relation between the Ω6 intensity parameter of Er3+ ions and the 151Eu isomer shift in oxide glasses. J. Appl. Phys. 73, 8451–8454 (1993).

Shinn, M., Sibley, W., Drexhage, M. & Brown, R. Optical transitions of Er3+ ions in fluorozirconate glass. Phys. Rev. B 27, 6635–6648 (1983).

Tarelho, L., Gomes, L. & Ranieri, I. Determination of microscopic parameters for nonresonant energy-transfer processes in rare-earth-doped crystals. Phys. Rev. B 56, 14344 (1997).

Wang, X. et al. Compositional dependence of the 1.8 μm emission properties of Tm3+ ions in silicate glass. J. Appl. Phys. 112, 103521 (2012).

McCumber, D. Einstein relations connecting broadband emission and absorption spectra. Phys. Rev. 136, A954–A957 (1964).

Choi, Y. G., Kim, K. H. & Heo, J. Spectroscopic properties of and energy transfer in PbO-Bi2O3-Ga2O3 glass doped with Er2O3 . J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 82, 2762–2768 (1999).

Payne, S. A., Chase, L., Smith, L. K., Kway, W. L. & Krupke, W. F. Infrared cross-section measurements for crystals doped with Er3+, Tm3+ and Ho3+. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 28, 2619–2630 (1992).

Zhao, G., Tian, Y., Fan, H., Zhang, J. & Hu, L. Efficient 2.7 μm emission in Er3+-doped bismuth germanate glass pumped by 980 nm laser diode. Chin. Opt. Lett. 10, 091601–091603 (2012).

Xu, R., Tian, Y., Hu, L. & Zhang, J. Enhanced emission of 2.7 μm pumped by laser diode from Er3+/Pr3+-codoped germanate glasses. Opt. Lett. 36, 1173–1175 (2011).

Tian, Y. et al. Fluorescence characteristics and energy transfer of ytterbium - sensitized erbium-doped fluorophosphate glass for amplifier applications. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transfer 133, 311–318 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos.LY13F050003, R14E020004), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 61308090, 51372235, 51172252 and 51272243), overseas students preferred funding of activities of science and technology project and International S&T Cooperation Program of China 2013DFE63070.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.W. wrote the main manuscript text. X.F.J., F.Z.C. and F.C.W. checked up. Y.T. and S.Q.X. were responsible for the experiment. J.J.Z. Q.Y.Z. and M.Z.C. proposed valuable suggestions for our manuscript revised. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, T., Tian, Y., Chen, F. et al. Mid-infrared fluorescence, energy transfer process and rate equation analysis in Er3+ doped germanate glass. Sci Rep 4, 6060 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06060

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06060

This article is cited by

-

Tuning the upconversion photoluminescence lifetimes of NaYF4:Yb3+, Er3+ through lanthanide Gd3+ doping

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Spectroscopic properties in Er3+-doped germanotellurite glasses and glass ceramics for mid-infrared laser materials

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

A hybrid strain and thermal energy harvester based on an infra-red sensitive Er3+ modified poly(vinylidene fluoride) ferroelectret structure

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Highly Tm3+ doped germanate glass and its single mode fiber for 2.0 μm laser

Scientific Reports (2016)

-

Controllable Phase Transformation and Mid-infrared Emission from Er3+-Doped Hexagonal-/Cubic-NaYF4 Nanocrystals

Scientific Reports (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.