Abstract

Translational GTPases (trGTPases) are involved in all four stages of protein biosynthesis: initiation, elongation, termination and ribosome recycling. The trGTPases Initiation Factor 2 (IF2) and Elongation Factor G (EF-G) respectively orchestrate initiation complex formation and translocation of the peptidyl-tRNA:mRNA complex through the bacterial ribosome. The ribosome regulates the GTPase cycle and efficiently discriminates between the GDP- and GTP-bound forms of these proteins. Using Isothermal Titration Calorimetry, we have investigated interactions of IF2 and EF-G with the sarcin-ricin loop of the 23S rRNA, a crucial element of the GTPase-associated center of the ribosome. We show that binding of IF2 and EF-G to a 27 nucleotide RNA fragment mimicking the sarcin-ricin loop is mutually exclusive with that of GDP, but not of GTP, providing a mechanism for destabilization of the ribosome-bound GDP forms of translational GTPases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In all domains of life protein biosynthesis on the ribosome follows the same functional cycle (for review see1). First, the ribosome associates with the mRNA and locates the start codon, which is recognized by initiator tRNA. Assembly of the initiation complex is regulated by several initiation factors; bacterial initiation factor 2 (IF2) and its eukaryotic and archaeal homologues eIF5B and aIF5B, respectively, are evolutionary conserved GTPases involved in ribosomal subunit joining and, in the case of IF2, additionally in initiator tRNA selection2. Upon formation of the initiation complex, the ribosome starts its elongation cycle: the A-site codon is decoded by the aminoacyl-tRNA delivered in complex with a GTPase protein - EF-Tu in bacteria, called eEF1A in eukaryotes and aEF1A in archaea3. Next, another GTPase - EF-G in bacteria, eEF2 in eukaryotes and aEF2 in archaea - catalyzes ribosomal translocation along the mRNA for one codon4,5. The elongation cycle repeats until the ribosome reaches the stop codon, which is decoded by a specialized release factor (RF1/RF2 in bacteria) that cleaves off the produced protein6. EF-G also has an additional role in ribosome recycling in bacteria, acting in concert with the ribosome recycling factor RRF to disassemble the post-termination complex7.

In vitro biochemical investigations have demonstrated that IF2 is switched to a functionally activated form by interactions with initiator tRNA (fMet-tRNAi), GTP and – to much lesser extent – GDP8. At physiologically relevant temperatures off the ribosome, both bacterial IF2 and eukaryotic eIF5B have somewhat lower affinity to GTP than to GDP9,10 and binding of G nucleotides is largely insensitive to IF2 binding to initiator tRNA11,12. IF2 interacts with the 30S ribosomal subunit via two binding sites, i.e. the N- terminus and domain II13,14 and in the context of the initiation complex, the latter interaction is strongly stimulated by GTP and fMet-tRNAi14.

Ribosomal translocation has been extensively studied in the bacterial system and relationships among the EF-G GTPase function and distinct stages of translocation are well understood (for review see5). Since in translocation GTP cannot be substituted for monoQ-purified GDP lacking trace amounts of GTP15,16,17,18, it is a prerequisite for successful translocation that while engaging the ribosome, either EF-G is in the GTP-bound form, or GDP is exchanged for GTP while EF-G is bound to the ribosome. Over the years, EF-G affinities to GTP and GDP have been measured both off and on the ribosome in several laboratories11,19,20,21,22,23. Off the ribosome, EF-G has a similar affinity to GTP and GDP, suggesting that in E. coli where the GTP concentration, depending on the growth conditions, is ~3–10 times higher than GDP24, most of the EF-G proteins are in the GTP-bound form19. On the ribosome, affinity to GTP increases dramatically16,22,23. According to the detailed balance principle25, there should also be a dramatic increase of EF-G:GTP affinity to the ribosome, compared to apo-EF-G. Such an increase in affinity has been confirmed experimentally23,26.

The effects of the ribosome on EF-G's interaction with GDP are not so well understood. Estimates of the dissociation rate constants (k−1) demonstrated that GDP dissociation is slowed down on the ribosome about ten-fold, which was interpreted as a stabilizing effect of the 70S on the EF-G:GDP complex22. However, in the absence of the association rate constants (k+1), a decrease in the dissociation rate does not necessarily mean that affinity increases, since Kd is a product of the division of the two rate constants (Kd = k−1 / k+1, given that the interaction has a simple one step binding mechanism). Moreover, k-1 estimates for GDP dissociation from the 70S:EF-G:GDP complex vary at least ten fold between different reports22,23, complicating the situation even further. This necessitates further investigations of the relationship between the ribosome and GDP binding to EF-G.

A powerful method for investigating thermodynamics of molecular interactions is Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) (for a review see27), which we have successfully applied in the study of complex formation between GTPases and their ligands, such as nucleotides, RNAs and proteins11,19,28. However, studying interactions with the ribosome presents a challenge for this approach due to technical reasons, such as molecular aggregation. So far, only experiments with ribosomal subunits have been successful29. One possible way of overcoming this limitation is to use isolated ribosomal components that mimic different functional centers – an approach that has been successfully applied to various biochemical and structural investigations of the translational apparatus30,31,32,33. While these partial systems necessarily overlook most of the complexity of the in vivo system, they have the advantage of allowing us to decouple one specific facet of the interactions from the others.

The sarcin-ricin loop (SRL), a part of the ribosomal RNA that is targeted by sarcin and ricin toxins (for review see34), is one of the most well-established oligonucleotide mimics31,32. In the native ribosomal complex, it directly interacts with EF-G and is crucial for activation of GTP hydrolysis35,36,37, though recent data suggest that is acts merely as an anchoring point for the EF-G on the ribosome and is not involved directly in the GTPase activation38,39. Similarly, the SRL was documented as crucial element for IF2 function on the ribosome: the interaction was first shown using chemical probing40 and later validated by several cryo-electron microscopy studies13,41.

Using a gel-retardation assay, a 27 nucleotide-long SRL RNA fragment was shown to bind to EF-G32. Surprisingly, SRL:EF-G complex formation is strongly inhibited by the presence of GDP and is insensitive to GDPNP, a non-hydrolysable GTP analogue. Differential effects of GDPNP and GDP, together with mutagenesis data suggest that the model reaction described by Munishkin and Wool32 reflects a relevant partial reaction rather than non-specific interaction between EF-G and the RNA oligonucleotide. Several questions, however, remain unanswered in the original report. First, GDPNP, even though it is a widely used mimic of GTP, does not have exactly the same properties and often has considerably lower affinity, therefore sometimes failing to represent the effects of GTP faithfully42,43,44. Since the SRL RNA oligonucleotide does not induce GTP hydrolysis on EF-G37, it is principally possible to perform ITC experiments with GTP rather than GDPNP. Second, by the detailed balance argument25, inhibition of EF-G:SRL complex formation by GDP suggests that SRL binding to EF-G should result in a strongly decreased affinity to GDP. This prediction has never been tested experimentally. Third, cross-talk between binding of G nucleotides and the SRL to other translational GTPases such as IF2 has never been investigated.

Results

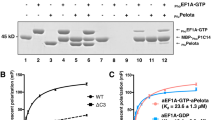

In the absence of nucleotides, EF-G associates with the SRL with a Kd of 5.9 μM at 5°C and 4.2 μM at 25°C (Figure 1A,Table 1), which is in satisfactory agreement with the ~7 μM Kd reported by Munishkin and Wool32. The complex formation has stoichiometry close to unity, indicating its specificity. The interaction is entropy driven (ΔH 4.94 kcal/mol vs TΔS 11.57 kcal/mol), suggesting a hydrophobic nature45. The addition of GTP at 500 μM had no significant effect on the interaction between EF-G and the SRL (Kd 3.7 vs 4.2 μM, Table 1). However, in the presence of 500 μM GDP, no complex formation was detected, again in good agreement with the results of Munishkin and Wool.

GDP and SRL binding to EF-G are mutually exclusive.

ITC titration curves (upper panel) and binding isotherms (lower panel) for the interaction of EF-G with SRL (A) in the absence (in black) and in the presence (in red) of 500 μM GDP and for the interaction of EF-G with GDP (B) in the absence (in black) and in the presence (in red) of 200 μM SRL at 25°C, pH 7.5.

After validating the inhibitory effect of GDP on SRL:EF-G complex formation, we tested the effects of the SRL on the binding of GDP and GTP to EF-G. In the case of GTP, the presence of 60 μM SRL had an insignificant effect on the interaction between EF-G and the nucleotide (Kd 2.4 vs 2.7 μM, Table 1). Binding of GDP, however, was considerably inhibited by the SRL, with apparent Kd increasing four times in the presence of 60 μM SRL (Table 1). The addition of 200 μM SRL to EF-G resulted in almost complete inhibition of GDP binding (Figure 1B), demonstrating the competition directly. To validate the specificity of the SRL:EF-G interaction, we employed an SRL G2655U mutant that displays dramatically weaker binding to EF-G as judged by gel-shift analysis32. Using 25 μM EF-G in the cell and 250 μM SRL G2655U in the syringe, we failed to detect binding at 4 and 25°C (data not shown). This indicates that the mutation indeed severely affects the Gibbs free energy and/or enthalpy of the interaction, in line with the results of Munishkin and Wool32.

Next, we investigated SRL interactions with IF2 (Table 2). In the absence of nucleotides, IF2 and the SRL form a considerably tighter complex than the SRL and EF-G (Kd 0.67 μM vs 4.2 μM at 25°C). This interaction was, as with EF-G, mostly entropy-driven (ΔH −2.27 kcal/mol vs TΔS 6.14 kcal/mol). Complex formation was largely insensitive to the GTP nucleotide (Kd of 1 μM in the presence of 500 μM GTP), and, again, just as in the case of EF-G, addition of 500 μM GDP inhibited the interaction between IF2 and SRL completely, both at 5°C and 25°C. Binding of GDP in the presence of 200 μM SRL was not detected, again indicating strong mutual competition between GDP and SRL binding.

In our recent ITC investigations of IF2 complex formation with fMet-tRNAi we observed no significant inhibitory effect of GDP, indicating the SRL:IF2 interaction is distinct from other IF2:RNA interactions11. To further investigate the specificity of the SRL:IF2 interaction, we analyzed IF2 binding to the SRL G2655U mutant. The G2655U mutation resulted in a modest two-fold increase in the Kd of IF2:SRL complex formation, but partitioning of the Gibbs free energy between the enthalpic and entropic components was dramatically altered (ΔH −2.27 kcal/mol and TΔS 6.14 kcal/mol for wt SRL vs ΔH −6.0 kcal/mol and TΔS 2.03 kcal/mol for the G2655U mutant). This effect, known as enthalpy-entropy compensation, is a hallmark of biological molecular interactions and is observed when a system is perturbed by temperature or ionic strength changes, mutations, binding of allosteric ligands etc.46.

Another ribosomal element that interacts with translational GTPases is ribosomal protein L7/L1247, which on the ribosome interacts with the G' domain of EF-G via its CTD domain35. The interaction between isolated L7/L12 and the apo-form of EF-G has been shown to be extremely weak (Kd = 0.4 ±0.1 mM), but it has been suggested that it could be affected by G nucleotides48, suggesting a possibility that interaction with L7/L12 could be responsible for the dramatic increase in EF-G affinity to GTP. Therefore we have analyzed L7/L12 binding to EF-G in a wide range of temperatures at increasing concentrations of the interacting partners. Even when EF-G at 400 μM was titrated with 4.7 mM L7/L12, the interaction signal was mainly dominated by the dilution heat (Supplementary Text S1: Supplementary Figure S1) and was not detectibly stimulated by addition of 1 mM GTP and GDP (data not shown).

Discussion

In this report we provide an in-depth thermodynamic analysis of the interaction of bacterial translational GTPases EF-G and IF2 with the SRL rRNA element. Recent investigations suggest a possibility that the SRL acts as an anchoring point for GTPase binding to the ribosome and is not implicated in GTPase activation per se38,39,49. Our complementary quantitative analysis demonstrates that binding of GDP and the SRL to GTPases IF2 and EF-G are mutually exclusive, while the thermodynamic profiles of complex formation between apo- and GTP-bound GTPases and the SRL are almost indistinguishable (Tables 1 and 2, Figure 2). Taken together, this suggests that apo- and GTP-bound forms of both EF-G and IF2 are efficiently discriminated by the SRL to the exclusion of the GDP-bound forms. The active role of GDP in regulation of the interaction of EF-G and IF2 with the SRL provides a mechanism for selective destabilization of GDP-bound forms of translational GTPases on the ribosome after GTP hydrolysis.

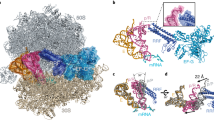

Comparison of cryo-EM reconstructions of ribosome-bound IF2:GDP and IF2:GDPNP shows that IF2 has extensive contacts with the SRL only in the GDPNP-bound complex50. This observation is in good agreement with our thermodynamic data demonstrating an inhibitory effect of GDP on the IF2:SRL interaction. The relatively low resolution of this cryo-EM reconstruction does not allow us to discern the molecular details of the IF2:SRL interface. However, the crystal structure of EF-G blocked on the ribosome in complex with GDP in the presence of fusidic acid provides an atomic level resolution the EF-G:SRL interface. The shoulders of domains III and V are in close proximity to the SRL, as are residues from the P loop, switch II and a conserved loop in between switch II and the G4 nucleotide binding motif (PDB IDs 2WRI and 2WRJ35 (Figure 3)). By having multiple contact points spanning three domains of the GTPase, the SRL may monitor the overall conformation of the protein, as well as specifically sensing the state of G-domain.

The SRL contacts three domains of EF-G.

EF-G is coloured by domains, as labeled on the figure. The SRL is shown as space-fill, in grey, while GDP and the magnesium ion are in yellow and green, respectively. The structure is taken from PDB IDs 2WRI and 2WRJ (the crystal structure of EF-G on the ribosome35).

Since interaction with SRL regulates both EF-G and IF2 binding to G nucleotides in the same manner – strong inhibition of GDP binding and virtually no effect on GTP binding – it is likely that the mechanism is the same in both cases. Allosteric effects are usually mediated via structural rearrangements; however, allostery mediated by changes in the conformational entropy without alterations of the overall structure is well documented51,52. Recent investigations of bacterial initiation factor IF2 showed profound structural rearrangements in the GDP-bound as compared to the apo-state9,53,54, in agreement with complementary biochemical experiments demonstrating the functional differences between the two8. However, in the case of EF-G, an absence of significant structural rearrangements in EF-G in the presence of G-nucleotides was suggested on the basis of Small Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS)55 and analysis of the changes in the Solvent Accessible Area (SAA) inferred from the ITC data19. However, it should be noted that both of these methods are intrinsically incapable of detecting structural rearrangements that do not lead to changes in the radius of gyration (SAXS) or SAA (ITC). In conclusion, we suggest that GDP is likely to exert its effects on SRL binding via alteration of conformational entropy by affecting protein motions rather than structure56. Direct validation of this prediction requires high-end NMR investigations focused on protein side chain dynamics57.

Further investigations are required in order to put the SRL effect into a kinetic framework of sequential interactions of IF2 and EF-G GTPases with the ribosome during their functional cycle. In the case of IF2, GDP was documented to have a weak activating effect on subunit joining8, which is likely connected to GDP-mediated rearrangements9,53,54. Time-resolved FRET studies of IF2 contacts with various components of the initiation complex – SRL, L7/12, fMet-tRNAi - are necessary in order to uncover the functional role of the SRL and GDP competition for IF2 binding.

Methods

EF-G, IF2, L7/12 and SRL preparations

The HPLC-purified SRL RNA oligonucleotide (wt 5′ GGGCUCCUAGUACGAGAGGACCGGAGU 3′ and G2655U mutant 5′ GGGCUCCUAUUACGAGAGGACCGGAGU 3′)32 was purchased from DNA Technology. The 6His tagged E. coli EF-G and IF2 cloned in the expression construct described by Forster and colleagues58 were overexpressed as described for the non-tagged IF259 and purified in essentially the same way, with an addition of a Ni-NTA purification step before the rest of the chromatographic procedures. Cloning, overexpression and purification of E. coli L7/L12 is described in Supplementary Text S1: SI Methods.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

The thermodynamic parameters of IF2 and EF-G binding to G nucleotides and the SRL RNA oligonucleotide were measured using a MicroCal iTC200 instrument (MicroCal, Northampton, MA) as described60. Experiments were carried out at 5 or 25°C in phosphate buffer (5 mM K2HPO4, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 95 mM KCl and 5 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5). 2.5-μl aliquots of ligands were injected into the 0.2-mL cell containing the protein solution to achieve a complete binding isotherm. Protein concentration in the cell ranged from 5 to 40 μM and ligand (G nucleotide or SRL RNA oligonucleotide) concentration in the syringe ranged from 50 to 500 μM. Investigations of EF-G binding to L7/L12 used 50 to 400 μM EF-G in the cell and up to 4.7 mM L7/L12 in the syringe. The heat of dilution was measured by injecting the ligand into the buffer solution or by additional injections of ligand after saturation; the values obtained were subtracted from the heat of reaction to obtain the effective heat of binding. The resulting titration curves were fitted using MicroCal Origin software using one binding site model. Interactions were characterized by stiochometry close to unity, indicating high activity and homogeneity of the protein and SRL preparations. Affinity constants (Ka), binding stoichiometry and enthalpy (ΔH) were determined by a non-linear regression fitting procedure. Idle GTP hydrolysis by GTPases during titration experiments was assessed by TLC and was not exceeding 1–2%.

References

Petrov, A., Kornberg, G., O'Leary, S., Tsai, A., Uemura, S. & Puglisi, J. D. Dynamics of the translational machinery. Curr Opin Struct Biol 21, 137–145 (2011).

Milon, P. & Rodnina, M. V. Kinetic control of translation initiation in bacteria. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 47, 334–348 (2012).

Wohlgemuth, I., Pohl, C., Mittelstaet, J., Konevega, A. L. & Rodnina, M. V. Evolutionary optimization of speed and accuracy of decoding on the ribosome. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 366, 2979–2986 (2011).

Kaul, G., Pattan, G. & Rafeequi, T. Eukaryotic elongation factor-2 (eEF2): its regulation and peptide chain elongation. Cell Biochem Funct 29, 227–234 (2011).

Rodnina, M. V. & Wintermeyer, W. The ribosome as a molecular machine: the mechanism of tRNA-mRNA movement in translocation. Biochem Soc Trans 39, 658–662 (2011).

Klaholz, B. P. Molecular recognition and catalysis in translation termination complexes. Trends Biochem Sci 36, 282–292 (2011).

Hirokawa, G., Demeshkina, N., Iwakura, N., Kaji, H. & Kaji, A. The ribosome-recycling step: consensus or controversy? Trends Biochem Sci 31, 143–149 (2006).

Pavlov, M. Y., Zorzet, A., Andersson, D. I. & Ehrenberg, M. Activation of initiation factor 2 by ligands and mutations for rapid docking of ribosomal subunits. EMBO J 30, 289–301 (2011).

Hauryliuk, V., Mitkevich, V. A., Draycheva, A., Tankov, S., Shyp, V., Ermakov, A., Kulikova, A. A., Makarov, A. A. & Ehrenberg, M. Thermodynamics of GTP and GDP binding to bacterial initiation factor 2 suggests two types of structural transitions. J Mol Biol 394, 621–626 (2009).

Pisareva, V. P., Hellen, C. U. & Pestova, T. V. Kinetic analysis of the interaction of guanine nucleotides with eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF5B. Biochemistry 46, 2622–2629 (2007).

Mitkevich, V. A., Ermakov, A., Kulikova, A. A., Tankov, S., Shyp, V., Soosaar, A., Tenson, T., Makarov, A. A., Ehrenberg, M. & Hauryliuk, V. Thermodynamic characterization of ppGpp binding to EF-G or IF2 and of initiator tRNA binding to free IF2 in the presence of GDP, GTP, or ppGpp. J Mol Biol 402, 838–846 (2010).

Antoun, A., Pavlov, M. Y., Andersson, K., Tenson, T. & Ehrenberg, M. The roles of initiation factor 2 and guanosine triphosphate in initiation of protein synthesis. EMBO J 22, 5593–5601 (2003).

Julian, P., Milon, P., Agirrezabala, X., Lasso, G., Gil, D., Rodnina, M. V. & Valle, M. The Cryo-EM structure of a complete 30S translation initiation complex from Escherichia coli. PLoS Biol 9, e1001095 (2011).

Caserta, E., Tomsic, J., Spurio, R., La Teana, A., Pon, C. L. & Gualerzi, C. O. Translation initiation factor IF2 interacts with the 30 S ribosomal subunit via two separate binding sites. J Mol Biol 362, 787–799 (2006).

Ermolenko, D. N. & Noller, H. F. mRNA translocation occurs during the second step of ribosomal intersubunit rotation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18, 457–462 (2011).

Zavialov, A. V., Hauryliuk, V. V. & Ehrenberg, M. Guanine-nucleotide exchange on ribosome-bound elongation factor G initiates the translocation of tRNAs. J Biol 4, 9 (2005).

Spiegel, P. C., Ermolenko, D. N. & Noller, H. F. Elongation factor G stabilizes the hybrid-state conformation of the 70S ribosome. RNA 13, 1473–1482 (2007).

Pan, D., Kirillov, S. V. & Cooperman, B. S. Kinetically competent intermediates in the translocation step of protein synthesis. Mol Cell 25, 519–529 (2007).

Hauryliuk, V., Mitkevich, V. A., Eliseeva, N. A., Petrushanko, I. Y., Ehrenberg, M. & Makarov, A. A. The pretranslocation ribosome is targeted by GTP-bound EF-G in partially activated form. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 15678–15683 (2008).

Arai, N., Arai, K. & Kaziro, Y. Further studies on the interaction of the polypeptide chain elongation factor G with guanine nucleotides. J Biochem 82, 687–694 (1977).

Baca, O. G., Rohrbach, M. S. & Bodley, J. W. Equilibrium measurements of the interactions of guanine nucleotides with Escherichia coli elongation factor G and the ribosome. Biochemistry 15, 4570–4574 (1976).

Wilden, B., Savelsbergh, A., Rodnina, M. V. & Wintermeyer, W. Role and timing of GTP binding and hydrolysis during EF-G-dependent tRNA translocation on the ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103, 13670–13675 (2006).

Ticu, C., Nechifor, R., Nguyen, B., Desrosiers, M. & Wilson, K. S. Conformational changes in switch I of EF-G drive its directional cycling on and off the ribosome. EMBO J 28, 2053–2065 (2009).

Buckstein, M. H., He, J. & Rubin, H. Characterization of nucleotide pools as a function of physiological state in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 190, 718–726 (2008).

Fersht, A. Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science: A Guide to Enzyme Catalysis and Protein Folding. (W. H. Freeman, 1998).

Zavialov, A. V. & Ehrenberg, M. Peptidyl-tRNA regulates the GTPase activity of translation factors. Cell 114, 113–122 (2003).

Roselin, L. S., Lin, M. S., Lin, P. H., Chang, Y. & Chen, W. Y. Recent trends and some applications of isothermal titration calorimetry in biotechnology. Biotechnol J 5, 85–98 (2010).

Chen, L., Muhlard, D., Hauryliuk, V., Zhihong, C., Lim, K., Shyp, V., Parker, R. & Song, H. Dom34-Hbs1 complex and implications for its role in No-Go decay. Nat. Struct. & Mol. Biol. 17, 1233–1240 (2010).

Osterman, I. A., Sergiev, P. V., Tsvetkov, P. O., Makarov, A. A., Bogdanov, A. A. & Dontsova, O. A. Methylated 23S rRNA nucleotide m2G1835 of Escherichia coli ribosome facilitates subunit association. Biochimie 93, 725–729 (2011).

Wong, L. E., Li, Y., Pillay, S., Frolova, L. & Pervushin, K. Selectivity of stop codon recognition in translation termination is modulated by multiple conformations of GTS loop in eRF1. Nucleic Acids Res 40, 5751–5765 (2012).

Endo, Y., Chan, Y. L., Lin, A., Tsurugi, K. & Wool, I. G. The cytotoxins alpha-sarcin and ricin retain their specificity when tested on a synthetic oligoribonucleotide (35-mer) that mimics a region of 28 S ribosomal ribonucleic acid. J Biol Chem 263, 7917–7920 (1988).

Munishkin, A. & Wool, I. G. The ribosome-in-pieces: binding of elongation factor EF-G to oligoribonucleotides that mimic the sarcin/ricin and thiostrepton domains of 23S ribosomal RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94, 12280–12284 (1997).

Bausch, S. L., Poliakova, E. & Draper, D. E. Interactions of the N-terminal Domain of Ribosomal Protein L11 with Thiostrepton and rRNA. J Biol Chem 280, 29956–29963 (2005).

Lacadena, J., Alvarez-Garcia, E., Carreras-Sangra, N., Herrero-Galan, E., Alegre-Cebollada, J., Garcia-Ortega, L., Onaderra, M., Gavilanes, J. G. & Martinez del Pozo, A. Fungal ribotoxins: molecular dissection of a family of natural killers. FEMS Microbiol Rev 31, 212–237 (2007).

Gao, Y. G., Selmer, M., Dunham, C. M., Weixlbaumer, A., Kelley, A. C. & Ramakrishnan, V. The structure of the ribosome with elongation factor G trapped in the posttranslocational state. Science 326, 694–699 (2009).

Moazed, D., Robertson, J. M. & Noller, H. F. Interaction of elongation factors EF-G and EF-Tu with a conserved loop in 23S RNA. Nature 334, 362–364 (1988).

Clementi, N., Chirkova, A., Puffer, B., Micura, R. & Polacek, N. Atomic mutagenesis reveals A2660 of 23S ribosomal RNA as key to EF-G GTPase activation. Nat Chem Biol 6, 344–351 (2010).

Chan, Y. L. & Wool, I. G. The integrity of the sarcin/ricin domain of 23 S ribosomal RNA is not required for elongation factor-independent peptide synthesis. J Mol Biol 378, 12–19 (2008).

Shi, X., Khade, P. K., Sanbonmatsu, K. Y. & Joseph, S. Functional Role of the Sarcin-Ricin Loop of the 23S rRNA in the Elongation Cycle of Protein Synthesis. J Mol Biol 419, 125–138 (2012).

La Teana, A., Gualerzi, C. O. & Dahlberg, A. E. Initiation factor IF 2 binds to the alpha-sarcin loop and helix 89 of Escherichia coli 23S ribosomal RNA. RNA 7, 1173–1179 (2001).

Simonetti, A., Marzi, S., Myasnikov, A. G., Fabbretti, A., Yusupov, M., Gualerzi, C. O. & Klaholz, B. P. Structure of the 30S translation initiation complex. Nature 455, 416–420 (2008).

Hauryliuk, V., Zavialov, A., Kisselev, L. & Ehrenberg, M. Class-1 release factor eRF1 promotes GTP binding by class-2 release factor eRF3. Biochimie 88, 747–757 (2006).

Hauryliuk, V., Hansson, S. & Ehrenberg, M. Cofactor dependent conformational switching of GTPases. Biophys J 95, 1704–1715 (2008).

Paleskava, A., Konevaga, A. L. & Rodnina, M. V. Thermodynamics of the GTP-GDP operated conformational switch of selenocysteine-specific translation factor SelB. J Biol Chem 287(33), 27906–12 (2012).

Perozzo, R., Folkers, G. & Scapozza, L. Thermodynamics of protein-ligand interactions: history, presence and future aspects. J Recept Signal Transduct Res 24, 1–52 (2004).

Lumry, R. Uses of enthalpy-entropy compensation in protein research. Biophys Chem 105, 545–557 (2003).

Diaconu, M., Kothe, U., Schlunzen, F., Fischer, N., Harms, J. M., Tonevitsky, A. G., Stark, H., Rodnina, M. V. & Wahl, M. C. Structural basis for the function of the ribosomal L7/12 stalk in factor binding and GTPase activation. Cell 121, 991–1004 (2005).

Helgstrand, M., Mandava, C. S., Mulder, F. A., Liljas, A., Sanyal, S. & Akke, M. The ribosomal stalk binds to translation factors IF2, EF-Tu, EF-G and RF3 via a conserved region of the L12 C-terminal domain. J Mol Biol 365, 468–479 (2007).

Garcia-Ortega, L., Alvarez-García, E., Gavilanes, J. G., Martínez-Del-Pozo, A. & Joseph, S. Cleavage of the sarcin-ricin loop of 23S rRNA differentially affects EF-G and EF-Tu binding. Nucleic Acids Res 38, 4108–4119 (2010).

Myasnikov, A. G., Marzi, S., Simonetti, A., Giuliodori, A. M., Gualerzi, C. O., Yusupova, G., Yusupov, M. & Klaholz, B. P. Conformational transition of initiation factor 2 from the GTP- to GDP-bound state visualized on the ribosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12, 1145–1149 (2005).

Tzeng, S. R. & Kalodimos, C. G. Dynamic activation of an allosteric regulatory protein. Nature 462, 368–372 (2009).

Tsai, C. J., del Sol, A. & Nussinov, R. Allostery: absence of a change in shape does not imply that allostery is not at play. J Mol Biol 378, 1–11 (2008).

Vohlander Rasmussen, L. C., Oliveira, C. L., Pedersen, J. S., Sperling-Petersen, H. U. & Mortensen, K. K. Structural transitions of translation initiation factor IF2 upon GDPNP and GDP binding in solution. Biochemistry 50, 9779–9787 (2011).

Wienk, H., Tishchenko, E., Belardinelli, R., Tomaselli, S., Dongre, R., Spurio, R., Folkers, G. E., Gualerzi, C. O. & Boelens, R. Structural dynamics of bacterial translation initiation factor IF2. J Biol Chem 287(14), 10922–32 (2012).

Czworkowski, J. & Moore, P. B. The conformational properties of elongation factor G and the mechanism of translocation. Biochemistry 36, 10327–10334 (1997).

Kalodimos, C. G. Protein function and allostery: a dynamic relationship. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1260, 81–86 (2012).

Kalodimos, C. G. NMR reveals novel mechanisms of protein activity regulation. Protein Sci 20, 773–782 (2011).

Forster, A. C., Weissbach, H. & Blacklow, S. C. A simplified reconstitution of mRNA-directed peptide synthesis: activity of the epsilon enhancer and an unnatural amino acid. Anal Biochem 297, 60–70 (2001).

Antoun, A., Pavlov, M. Y., Tenson, T. & Ehrenberg, M. M. Ribosome formation from subunits studied by stopped-flow and Rayleigh light scattering. Biol Proced Online 6, 35–54 (2004).

Mitkevich, V. A., Kononenko, A. V., Petrushanko, I. Y., Yanvarev, D. V., Makarov, A. A. & Kisselev, L. L. Termination of translation in eukaryotes is mediated by the quaternary eRF1*eRF3*GTP*Mg2+ complex. The biological roles of eRF3 and prokaryotic RF3 are profoundly distinct. Nucleic Acids Res 34, 3947–3954 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Pohl Milon for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the Presidium of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Program Molecular and Cellular Biology to AAM); Estonian Science Foundation grants (grant numbers 7616, 9012 to VH, 6768 to TT and 9020 to GCA); the European Social Fund through Estonian Science Foundation grants (grant number MJD99 Mobilitas to GCA); the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (grant number 10-04-01746-a to VAM); European Regional Development Fund through the Center of Excellence in Chemical Biology (VH and TT) and SA Archimedes PhD studies and DoRa6 programme grants (VS). Funding for open access charge: European Regional Development Fund through the Center of Excellence in Chemical Biology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VH conceived the project, coordinated the study and drafted the paper with contributions from VAM, VS, GCA, TT and AAM. VAM, VS, IYuP, AS, VH performed experiments. GCA analyzed the structural data. AAM and TT coordinated the study and contributed materials and reagents.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supporting information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Mitkevich, V., Shyp, V., Petrushanko, I. et al. GTPases IF2 and EF-G bind GDP and the SRL RNA in a mutually exclusive manner. Sci Rep 2, 843 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00843

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00843

This article is cited by

-

Direct interaction of beta-amyloid with Na,K-ATPase as a putative regulator of the enzyme function

Scientific Reports (2016)

-

Initiation of mRNA translation in bacteria: structural and dynamic aspects

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.