Key Points

-

Highlights poor oral health of care home residents in Wales and compares their oral health status to similar age older people living in the community.

-

Highlights need for better oral care and prevention and monitoring mechanism.

Abstract

Background UK adult dental health surveys (ADHS) exclude care home residents from sampling. Aim To understand oral health status of care home residents in Wales using ADHS criteria.

Method Cross sectional survey of care home residents in Wales using a questionnaire and oral examination contemporaneous with, and paralleling, the ADHS 2009. 708 randomly selected participants from 213 randomly selected care homes participated including individuals with and without capacity.

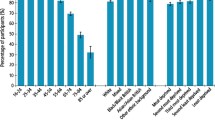

Results 72.8% of residents had tooth decay. Compared to older adults examined in the ADHS, residents are less likely to brush teeth/dentures twice a day (37% vs 63%), more likely to only attend a dentist when they have a problem (63% vs 26%), have more teeth with active decay (3.1 vs 0.9), more have current dental pain (13% vs 5%) and other morbidity (open pulp, ulceration, fistulae, abscess 27% vs 10%). High decay is present in both recently admitted and longer term residents. There was some regional variation in levels of oral hygiene.

Conclusion Oral health status of older people resident in care homes in Wales is poor. Findings suggest more could be done to improve preventive care both before and after admission to the care home.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The UK population is ageing and is projected to continue ageing over the next few decades with the fastest population increases in the numbers of those aged 85 and over.1 A greater proportion of older people in future are more likely to retain their teeth compared to earlier cohorts. In 1968, 37% of adults in Wales were edentulous compared to 10% in 2009.2 With ageing and an increasing dentate older population, the delivery of prevention and dental care to this population needs to be reassessed and better planned.

A survey of care home managers in Wales in 2006/7 indicated geographical variation and problems with access to appropriate dental services for care home residents.3 This survey also highlighted that many care homes (nursing and residential) in Wales did not undertake routine oral health assessment or use recorded oral care plans.

Decennial ADHS in the UK have excluded older people living in care homes and other vulnerable adults.4 With reported problems in accessing dental care,3 it is important to understand oral health status and any inequalities in oral disease for the care home population compared with non-dependent older adults living in the community. Such comparative information is useful for needs assessment, advocacy and planning of future dental services. Therefore, in Wales, the 2009/10 ADHS was complemented by a dental health survey of care home residents in 2010/11 using the ADHS clinical criteria. The main aim of this study was to understand oral health status of care home residents in Wales and how it compared to older adults of similar age group as reported in the ADHS, 2009/10.

Methods

The survey was planned in parallel with the ADHS 2009. Data was collected through interview using a structured questionnaire and oral examination. The Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee (MREC) in Wales approved the study and agreed that the study should include both residents with and without capacity to consent. Data was collected between October 2010 and June 2011. Twelve examiners (dentists) and their recorders (dental nurses) working in the Community Dental Services (CDS) in Wales collected the data. They were trained in the requirements of the Mental Capacity Act 2005, consent, clinical criteria, data entry and adult safeguarding.

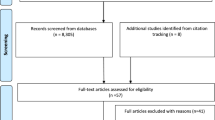

A sample of 228 care homes (residential and nursing) from 22 local authority (LA) areas were randomly selected from the Care and Social Services Inspectorate Wales list of care homes and invited to participate in the study. Where a care home declined another, randomly selected from the same LA area, was invited to participate. Five residents were randomly selected from each care home (all if there were only five or fewer) and invited to participate in the survey. Consent was sought from those residents able to consent. For those without capacity, consent was sought for an oral examination from a person with lasting power of attorney or a court appointed deputy. If neither of these were available the person without capacity was excluded from the survey. The clinical examination was expected to take a little longer on average for those participating care home residents who lacked capacity. It was anticipated that this would be compensated for by these individuals not participating in the questionnaire elements of this survey. It was estimated that data collection on up to five residents in a care home would require a clinical session of 3 - 3.5 hours. If a selected resident refused to participate in the survey, he/she was not replaced with another resident. Participants were free to withdraw from data collection at any point when they felt unwilling or unable to continue.

Oral examinations were carried out within the care homes using a purpose-built (Daray) lamp (designed to yield 4,000 lux at one metre), mouth mirrors, Type C periodontal probe and a sharp probe for diagnosis of root surface decay. Visually obvious tooth decay extending into dentine was recorded. Details of the examination criteria can be found in the survey protocol available from the Welsh Oral Health Information Unit at Cardiff University (http://www.cardiff.ac.uk/cy/dentistry/research/themes/applied-clinical-research-and-public-health/epidemiology-and-applied-clinical-research/wohiu).

Data was analysed using the SPSS version 18. Findings for dentate (with at least one natural tooth present) care home residents were compared with findings for older age dentate adults published following the 2009/10 ADHS.4 Residents were also divided into groups based on capacity to consent, bed type (nursing or residential), and length of stay in a care home to explore differences within care home residents. Variations between regions within Wales were also explored.

Results

In total 213 care homes and 708 residents (95 in nursing bed and 613 in residential bed within participating care homes) participated in the survey (see Fig. 1). Of the participants 321 were dentate (at least one natural tooth) and 387 were edentate. Seventy-six participants (10.7%) did not have the capacity to consent. Full dental examination was possible for 279 dentate residents. Average ages of edentate and dentate residents were similar and in the mid-eighties. Detailed demographics and findings on some factors relevant for oral health of care home residents are presented in Table 1. Dry mouth was reported by a quarter of participants. Oral care and access to dental care was poor as measured by reported frequency of tooth/gum cleaning, denture cleaning and dental visit patterns.

Statistically significant regional differences were found between South West Wales and Mid & North Wales in both oral hygiene status of dentate residents and reported denture cleaning (two or more times a day). Thirty six percent (95% CI – 30.3% to 42.1%) of dentate residents in South West Wales had poor or very poor oral hygiene compared to 16.2% (95% CI – 11.4% to 22.5%) in Mid & North Wales. Similarly, 23.6% (95% CI – 17.8% to 30.6%) of care home residents in South West Wales reported denture cleaning twice a day or more compared to 43% (95%CI – 34.3% to 52.2%) in id & North Wales.

Overall, oral health of care home residents was poorer compared to non-dependent older adults living in the community as reported by the ADHS, 2009/10. Forty-five percent (321/708) of care home residents were dentate compared to 53% of non-dependent older people (85 years and over) living in the community.4 Table 2 compares care home survey findings for dentate adults with those from the ADHS 2009 for older age groups. Even though care home residents have similar numbers of teeth to peers in the community there are some stark findings. Care home residents are almost twice as likely to have some active decay and, on average, three times as many teeth with active decay. This may partly explain why they are also 2.5 times more likely to report current pain or to have open pulp, traumatic ulceration, fistula or abscess (PUFA). Lower reported levels of cleaning teeth and higher reported levels of only attending a dentist when trouble presents may also partly explain the higher levels of oral disease and symptoms among dentate care home residents.

Comparison between various resident groups based on capacity to consent, type of bed used by the residents (nursing/residential) and length of stay (less than a year and one year or more) did not reveal any significant differences, and 68.6% of care home residents who had only been living in the care homes for less than a year had active tooth decay.

Discussion

Methodological limitations of this study include lack of calibration between dental examiners and inability to access information on non-participating care homes and residents. Calibration of twelve examiners with care home residents was considered inappropriate considering the frailty of the survey participants, however, many of the examiners had trained and calibrated for the ADHS. The participation rate for this study was similar to that obtained for the ADHS. One of the strengths of this study is that the oral examination element of the survey included residents who did not have capacity to consent, however, comparison between different types of residents, including those with and without capacity to consent, was limited by sample size.

This study excluded residents unable to consent and for whom no one had been appointed with lasting power of attorney. In the absence of data on the oral health status of this excluded group one can only assume that they had oral health similar to that of peers for whom there was someone with lasting power of attorney. Given that there was no statistically significant difference in oral health status between those care home residents with and without capacity to consent this assumption seems reasonable.

High prevalence of tooth decay in residents who have only been in the care homes for less than a year suggests that many residents enter care homes with tooth decay. This is consistent with findings from a previous study in Australia.5 This suggests that action will need to be upstream of admission to the care home to prevent decay.

Studies among older adults have demonstrated that oral diseases often lead to dysfunction, discomfort and affect well-being.6,7 Despite the known effect of poor oral health on older people, oral health care needs of dependent older people are being neglected and access to dental care is problematic.3,8,9 Recent studies indicate that poor oral hygiene may also be a risk factor for aspiration pneumonia.10,11 The cost of implementing oral hygiene is minimal compared to medical expenditure required to manage aspiration pneumonia.

Unclear responsibility of carers for oral care, absence of oral hygiene guideline and routines, lack of training and psychological issues have all been identified as barriers in carers' provision of oral care to residents.8,12 Regional variations in oral and denture hygiene of care home residents found in this study suggest that it should be possible to raise standards of oral hygiene. Setting national standards of oral care and prevention in care homes, providing training for staff and monitoring the delivery of oral health care through a care homes inspection programme may improve oral care in care homes and reduce some of the inequalities reported in this study.

It is important to avoid the trap of focusing only on people currently vulnerable and seek opportunities to intervene early to support those who may become vulnerable in future. To improve oral health of older people living in care homes, more priority needs to be given to integrate good oral care and prevention into care planning of older people well before and after admission into care homes. There should also be systems in place to monitor delivery of oral care to dependent older people.

Although there were some methodological limitations, this study provides important information on the dental health of care home residents in Wales and raises challenges that government, health boards and local authorities in Wales face in improving the oral health of older people, especially care home residents.

Conclusion

Oral health of residents is poorer than that of older adults examined in the ADHS in terms of oral hygiene practice, decayed teeth and pain experience and other morbidity (PUFA). This is true for both recently admitted and longer term residents. Setting national standards for oral care and prevention in care homes, providing staff training and monitoring oral care delivery through a care home inspection programme may reduce some inequalities in oral health suffered by care home residents. Action will also be needed before admission to the care home to maximise the oral health of care home residents.

References

Office for National Statistics. Population ageing in the United Kingdom, its constituent countries and the European Union. London: Office for National Statistics, 2012. Available online at http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171776_258607.pdf (accessed September 2015).

Chenery V, Treasure E . Adult dental health survey 2009 – Wales key findings. Sullivan I (ed). Leeds: The Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2011. Available online at http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB01086/adul-dent-heal-surv-summ-them-wale-2009-re13.pdf (accessed September 2015).

Monaghan N, Morgan M Z . Oral health policy and access to dentistry in care homes. J Disab Oral Health 2010; 11: 61–68.

Health and Social Care Information Centre. Adult dental health survey 2009 – Summary report and thematic series. Available online at http://www.hscic.gov.uk/pubs/dentalsurveyfullreport09 (accessed September 2015).

Chalmers J M, Carter K D, Fuss J M, Spencer A J, Hodge C P . Caries experience in existing and new nursing home residents in Adelaide, Australia. Gerodontology 2002; 19: 30–40.

Slade D, Spencer A J, Locker D, Hunt R J, Strauss R P, Beck J D . Variations in the social impact of oral conditions among older adults in South Australia, Ontario and North Carolina. J Dent Res 1996; 75: 1439.

Petersen P E, Yamamoto T . Improving the oral health of older people: the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2005; 33: 81–92.

Fiske J, Lloyd H A . Dental needs of residents and carers in elderly people's homes and carers' attitudes to oral health. Eur J Prosthodont Rest Dent 1992; 20: 106–111.

Frankel H, Harvey I, Newcombe R G . Oral health care among nursing home residents in Avon. Gerodontology 2000; 17: 33–38.

Azarpazhooh A, Leake J L . Systematic review of the association between respiratory diseases and oral health. J Periodontol 2006; 77: 1465–1482.

Pace C C, McCullough G H . The association between oral microorganisms and aspiration pneumonia in the institutionalised elderly: review and recommendations. Dysphagia 2010; 25: 307–322.

Sonde L, Emami A, Kiljunen H, Nordenram G . Care providers' perceptions of the importance of oral care and its performance within everyday caregiving for nursing home residents with dementia. Scand J Caring Sci 2011; 25: 92–99.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the care home residents and staff who took part in this study and the community dental service personnel who acted as examiners and data recorders. We would also like to acknowledge the support of the Chief Dental Officer for Wales for his support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Karki, A., Monaghan, N. & Morgan, M. Oral health status of older people living in care homes in Wales. Br Dent J 219, 331–334 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.756

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.756

This article is cited by

-

Measurement properties, interpretability and feasibility of instruments measuring oral health and orofacial pain in dependent adults: a systematic review

BMC Oral Health (2022)

-

Perspectives of community-dwelling older adults with dementia and their carers regarding their oral health practices and care: rapid review

BDJ Open (2021)

-

Gwên am Byth: a programme introduced to improve the oral health of older people living in care homes in Wales - from anecdote, through policy into action

British Dental Journal (2020)

-

How do we incorporate patient views into the design of healthcare services for older people: a discussion paper

BMC Oral Health (2018)

-

The knowledge mobilisation challenge: does producing evidence lead to its adoption within dentistry?

British Dental Journal (2018)