Abstract

Study design:

Descriptive qualitative and quantitative study using cross-sectional data from the Swiss Spinal Cord Injury Cohort Study (SwiSCI).

Objective:

To determine the key demands and characteristics of occupations performed by individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI).

Setting:

Swiss community.

Methods:

Job titles indicated by SwiSCI participants were linked to occupational titles from the Occupational Information Network (O*NET) and then frequency-analyzed across sociodemographic and injury-related factors. Subsequently, average O*NET relevance values ranging from 0 to 100 were calculated for the occupations’ demands and characteristics, both in general and stratified by injury-related factors.

Results:

The 1549 study participants indicated a total of 717 job titles and were primarily employed in administrative and management occupations (22.1% and 16.4%, respectively). The participants’ occupations predominantly required verbal abilities (average relevance [AR]=68.4) and complex problem solving skills (AR=55.8) and were characterized by conventional work tasks (AR=62.9) and social relationships (AR=58.6). Both the occupations’ frequency distribution as well as the average relevance levels of their demands and characteristics differed by SCI severity.

Conclusions:

Individuals with SCI perform a broad range of occupations that are mainly characterized by cognitive and communicative demands, while physical demands are of minor importance. By informing the development of job matching profiles for vocational guidance, our study facilitates the determination of well-matching jobs for persons with SCI and may contribute to a more sustainable return to work of the affected persons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sustaining a spinal cord injury (SCI) is an incisive life event that commonly confronts affected individuals with the challenge of finding and settling into a new job that matches their capabilities, preferences and values. Employment rates typically decrease after SCI onset,1 ranging internationally from 11.5 to 74.0%.2 For Switzerland, an employment rate of 53.4% has recently been reported, which is roughly 30% points lower compared with the general population.3 Like in the general population, the labor market participation of individuals with SCI is influenced by sociodemographic factors such as age or education, but beyond that also by injury-related factors such as SCI severity or age at injury.4

Because work represents an important path to social participation and quality of life for persons with SCI,5 work reintegration is a major goal of SCI rehabilitation.6 Establishing well-matching jobs for persons with SCI in the context of vocational guidance requires adequate knowledge on occupations that are successfully performed post SCI. For the purpose of the present study, we refer to the term ‘occupation’ to describe both paid employment as well as unpaid work such as, for instance, sheltered employment. Studies from various countries indicate that individuals are predominantly used in administrative, clerical, professional and social service occupations after SCI onset.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Yet with the exception of Hwang et al.13 who linked occupations of US individuals with SCI to the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC-2010),14 these studies do not make use of an international job classification standard, which precludes useful comparisons with the general population, or across countries. Furthermore, most previous studies fall short of providing comprehensive information on the effective demands and characteristics of post SCI occupations. While Sinden et al.15 offered interesting insights into physical and sensory demands as well as educational requirements, they did not examine the cognitive demands, required skills and knowledge, typical work context, prevailing work style or interest pattern of post SCI occupations, all of which are important aspects for determining a person-job match in vocational guidance.16, 17

To address these gaps in previous research, the present study draws on the Occupational Information Network (O*NET),18, 19, 20 which represents the currently most up-to-date standardized occupational information system available. The O*NET is based on the SOC-2010 and hierarchically organizes 1110 occupational titles of the US labor market into 23 major groups (e.g., 29-0000 Health-care practitioners and technical occupations), 97 minor groups (e.g., 29-1000 Health diagnosing and treating practitioners), 461 broad occupations (e.g., 29-1060 Physicians and surgeons) and 841 detailed occupations (e.g., 29-1062 Family and general practitioners). Moreover, the O*NET provides a comprehensive set of demands (i.e., required abilities, skills, knowledge, work styles and work activities) and characteristics (i.e., prevailing interest pattern, work values and work context) for these occupations. This set is hierarchically arranged into supercategories (e.g., cognitive abilities), subcategories (e.g., verbal abilities) and specific descriptors (e.g., oral comprehension), of which the latter are equipped with values indicating their relevance for each O*NET occupation on a scale from 0 to 100.

In the present study, we used the O*NET to determine the key demands and characteristics of occupations performed by individuals with SCI living in Switzerland. More specifically, we aimed:

-

1

(a) to identify occupations of individuals with SCI and link them to occupational titles from the O*NET, and (b) to calculate the frequency of these O*NET titles stratified by sociodemographic and injury-related factors;

-

2

(a) to determine the relevance of the O*NET demands and characteristics across the identified occupations, and (b) to compare their relevance across occupations of individuals with different SCI severities and walking abilities.

Materials and methods

Design and participants

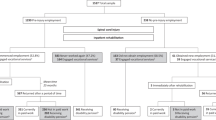

The present study applied a descriptive design involving a qualitative and quantitative analysis of cross-sectional data from the basic module of the Swiss SCI Cohort Study (SwiSCI) community survey21, 22 conducted between late 2011 and early 2013. The SwiSCI community survey covered Swiss residents with a traumatic or non-traumatic SCI who were aged 16 years and more at the time of the survey.22 Excluded were congenital conditions leading to SCI (e.g., spina bifida), new SCI in the context of palliative care, neurodegenerative disorders (e.g., multiple sclerosis) and Guillain-Barré syndrome. The SwiSCI study was approved by the responsible ethical committee. Details on its design and recruitment strategy has been published previously.21 For the purpose of the present study, we focused on participants reporting at least one job title at the time of the survey. We first classified the indicated job titles to occupational titles from the O*NET and then determined the frequency of the O*NET titles and the relevance of their demands and characteristics.

Measures

The participant’s job title was determined by a free-text response format question (i.e., ‘What is the name or title of your current main job?’). Sex, age at survey in years and education level in years of formal education were used as sociodemographic stratification variables. Injury-related stratification variables included SCI severity, walking ability and age at injury in years. SCI severity was determined as a combination between SCI level (i.e., paraplegia or tetraplegia) and SCI degree (i.e., complete or incomplete), both measured by self-report questions. In the survey, complete lesions were explained as having no motor or sensory functions below lesion level and incomplete lesions as some of the motor or sensory functions being retained below lesion level. Walking ability was measured using the item ‘moving around moderate distances (10 to 100 m)’ from the Spinal Cord Independence Measure III (SCIM-SR)23 and dichotomized into manual or electric wheelchair users and individuals who are able to walk.

Data analysis

To systematically classify occupations of persons with SCI, the stated job titles were linked to the most precise O*NET occupational title. The linking was conducted independently by the first and the senior author; any discrepancies were discussed until resolved. Inter-rater reliability was determined based on percentage agreement. For the subsequent frequency analysis, the occupational titles were aggregated to the O*NET major group level.

To determine the relevance of the occupations’ demands and characteristics, we first extracted for each identified O*NET title the relevance values of its specific descriptors from the O*NET database (http://www.onetonline.org) We then calculated the average relevance value of the specific descriptors and the O*NET sub- and supercategories across all identified titles. Finally, we calculated and compared the average relevance values of the sub- and supercategories across occupations of individuals with different levels of SCI severity and walking ability. Data extraction and statistical analyses were conducted using the programming software R (version 3.3.2).24

Results

Sample characteristics

The basic module of the SwiSCI community survey was completed by 1549 participants, representing at least 25% of the estimated total Swiss SCI adult population in 2012.21 As response bias was restrained, the sample can be considered representative of the Swiss SCI population. At the time of the survey, 1198 of the study participants were of employable age (the statutory retirement age in Switzerland is 64 years for women and 65 years for men). Of these, 671 (56.0%) were gainfully employed.22 A total of 677 participants reported at least one job title and represented thus our study sample, whose sociodemographic and injury-related characteristics are presented in Table 1. The present study not only considered job titles of gainfully employed participants but also of participants engaged in unpaid work such as, for instance, sheltered employment.

Occupations performed by individuals with SCI

Participants reported a total of 717 job titles, of which 701 could be linked to 237 different O*NET titles. Sixteen unclassifiable job titles (e.g., ‘employee’) were excluded. Inter-rater reliability was 80.9% on the O*NET major group level and 58.8% on the detailed occupation level.

Table 2 presents the frequencies of the occupational titles across O*NET major groups and stratified by sociodemographic and injury-related factors. The participants’ occupations covered all 23 major groups except Military Specific Occupations. Office and Administrative Support Occupations (22.1%), Management Occupations (16.4%) and Architecture and Engineering Occupations (10.4%) were most frequently reported, whereas crafts occupations such as Construction and Extraction Occupations (1.4%), Transportation and Material Moving Occupations (1.7%) or Production Occupations (4.0%) were stated less frequently.

The stratified analysis for sex revealed that males worked more commonly in Management Occupations (19.2% vs 6.9%) and Architecture and Engineering Occupations (12.4% vs 3.8%) than females, but less frequently in Office and Administrative Support Occupations (17.7% vs 36.9%) and Education, Training and Library Occupations (4.4% vs 16.9%). When stratifying for age at survey, we found a decreased frequency of Office and Administrative Support Occupations and Architecture and Engineering Occupations with older age (i.e., from 37.9% in the age group 16–24 years to 15.6 and 4.8% in the group 55–63/64 years), whereas Management Occupations were more prevalent in older participants (i.e., 19.7% in the age group 55–63/64 years vs 6.9% in the group 16–24 years). Finally, individuals with a university education level worked more commonly in Education, Training and Library Occupations (13.2% vs 0.0–7.1%) and Health-care Practitioners and Technical Occupations (10.1% vs 0.0–1.9%) than participants with a lower education.

When stratifying for SCI severity, a more narrow range of occupations covering only 15 out of 23 O*NET major groups became evident for complete tetraplegics. They were comparatively often employed in Architecture and Engineering Occupations (15.1% vs 7.4–11.4%) and Legal Occupations (9.6% vs 0.8–3.3%), but less frequently in Management Occupations (8.2% vs 16.5–19.8%) and Production Occupations (0.0% vs 2.5–7.3%). Similarly, wheelchair users worked less often in Production Occupations than individuals who are able to walk (1.8% vs 7.8%), but more often in Office and Administrative Support Occupations (26.5% vs 13.1%). Finally, individuals with the youngest age at injury (<16 years) were more commonly engaged in Office and Administrative Support Occupations (34.4% vs 8.0–25.0%), but less frequently in Production Occupations (1.6% vs 3.0–7.0%) and Construction and Extraction Occupations (0.0% vs 0.0–3.4%) than participants aged 16–63/64 years at injury.

Demands and characteristics of occupations performed by individuals with SCI

The average relevance levels of the O*NET super- and subcategories reflecting the demands and characteristics of our participants’ occupations are presented in Table 3. Table 4 shows the differences in the average relevance levels of the super- and subcategories across occupations of individuals with different levels of SCI severity and walking ability.

Demands of the occupations

Abilities: Cognitive abilities (M=45.6), in particular its subcategories verbal and idea generation and reasoning abilities (M=68.4 and M=57.2), represented the most relevant ability demands, whereas physical and psychomotor abilities (M=10.5; M=19.8) appeared least relevant, with particularly low values in occupations of individuals with complete lesions (M=6.2 and M=15.8 for complete tetraplegics; M=8.6 and M=17.8 for complete paraplegics) and wheelchair users (M=8.3; M=17.4).

Skills: Basic skills (M=54.4) with its subcategories process- and content-related basic skills (M=54.9; M=53.8) were generally more relevant than cross-functional skills (M=42.2), although the latter’s subcategories complex problem solving and social skills (M=55.8; M=51.1) showed comparably high relevance values too. Complex problem solving skills were particularly important in occupations of complete tetraplegics (M=58.3). The subcategory technical skills was least relevant (M=17.3) and showed particularly low values in occupations of wheelchair users (M=16.2).

Knowledge: Business and management (M=46.1) and education and training (M=45.4) were the most relevant knowledge demands, whereas health services (M=17.4) and manufacturing and production (M=19.0) were least relevant. Knowledge on manufacturing and production showed a particularly low relevance in occupations of complete tetraplegics (M=14.3) and wheelchair users (M=17.6).

Work styles: Conscientiousness (M=86.5) appeared most relevant across the work style domain, while social influence (M=68.1) and practical intelligence (M=69.4) were least relevant. Yet practical intelligence showed a higher relevance in occupations of complete tetraplegics (M=72.4) and wheelchair users (M=70.4).

Work activities: Mental processes (M=61.1) and information input (M=60.7), in particular their subcategories looking for and receiving job information (M=69.3) and reasoning and decision making (M=62.3), were the most relevant work activities demands. Work output (M=35.6) with its subcategory performing physical and manual work activities (M=30.6) appeared least relevant, especially in occupations of complete tetraplegics (M=32.2) and wheelchair users (M=34.4).

Characteristics of the occupations

Occupational interests: Conventional (M=62.9) and enterprising interests (M=55.6) were most relevant across the occupational interest domain, while realistic interests (M=44.2) appeared particularly important in occupations of individuals who are able to walk (M=50.6). Artistic and investigative interests were generally least important (M=22.1 and M=34.8), but investigative interests were especially relevant in occupations of complete tetraplegics (M=44.8).

Work values: Human relationships (M=64.7) were most and recognition (M=48.9) least relevant among the work values. Yet recognition showed higher relevance values in occupations of persons with tetraplegia (M=53.9 for complete tetraplegics and M=51.4 for incomplete tetraplegics).

Work context: Interpersonal relationships (M=58.6) appeared most relevant, mainly due to its subcategories communication (M=73.8) and role relationships (M=70.6). Physical work conditions were least relevant (M=24.3), especially in occupations of individuals with complete lesions (M=20.4 for complete tetraplegics and M=22.8 for complete paraplegics) and wheelchair users (M=22.3).

Discussion

The present study used the O*NET to analyze the demands and characteristics of occupations of individuals with SCI living in Switzerland. Participants worked in a broad range of occupations covering almost all O*NET major groups and mainly performed administrative, management, architecture and engineering occupations, but less often crafts occupations. While cognitive abilities, social and problem solving skills, a conscientious work style and work activities involving mental processing represented the occupations’ key demands, conventional interests as well as work values and a work context related to social relationships turned out to be the occupations’ key characteristics. Both the occupations’ prevalence as well as their demands and characteristics varied across different SCI severities and walking abilities.

Occupations of individuals with SCI

Our finding that individuals with SCI are predominantly employed in administrative, management and academic occupations but hardly in the crafts sector corroborates previous research.10, 13, 15 In a current study based on the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-08),25 we found that compared with the Swiss general population individuals with SCI work more frequently in office, management and academic occupations, but less commonly in crafts, service and sales occupations.26 Our present findings that managerial occupations post SCI are more prevalent in males and individuals with an older age or a higher education and clerical and teaching occupations are more common in females also reflect the situation of the general population.26, 27

The injury-related differences we established in the occupations’ prevalence indicate that certain occupations may be more and others less suitable for particular SCI groups. For instance, the narrow range of occupations and the low frequency of crafts and management occupations in complete tetraplegics on the one hand, and the high prevalence of academic occupations on the other, indicate restricted vocational opportunities compared with less severely injured individuals. They also suggest a particular suitability of non-manual occupations that are cognitively demanding and often require a higher education, which is in line with Schwegler et al.28 who showed that complete tetraplegics with a physically demanding pre-injury job tend to switch to academic occupations post SCI. The low prevalence of management occupations may be due to the severe mobility limitations and secondary health conditions of complete tetraplegics preventing them from working full time.1

Key demands and characteristics of occupations of individuals with SCI

Idea generation, reasoning and problem solving, and also verbal abilities and social skills were highly relevant across our study participants’ occupations. Together with the high relevance of knowledge on business, management, education and training, and of work activities involving mental processing and information input, this implies a particular suitability of cognitively and communicatively demanding occupations for persons with SCI. With regard to the importance of communicative demands, our results are thus in line with Sinden et al.15 In addition, the finding that physical and psychomotor abilities, manual work activities, technical skills and knowledge on manufacturing and production were least relevant across our participants’ occupations reflects the low prevalence of physically demanding occupations in our sample.

In accordance with the importance of social and communicative demands, we established social relationships to be key characteristics in both the work values and the work context domain. This finding may be explained by the importance of social interactions in managerial occupations that are highly prevalent in our sample, and also reflects the key role social contacts have as incentives to work for persons with SCI.29 The work value recognition was a common characteristic of occupations of tetraplegics, which might be attributed to occupations requiring a higher education (e.g., academic occupations) that were frequent among tetraplegics and that typically address this particular work value. Moreover, we established conventional and enterprising interests to be of general importance across our participants’ occupations and investigative interests of particular relevance for the chiefly academic occupations of complete tetraplegics. These findings represent an interesting contrast to Krause et al.30 who found that US males with recent-onset SCI have primarily realistic and females mainly social, enterprising and conventional occupational interests, but that both sexes score low on investigative interests. Based on these differences, it appears that individuals with SCI return to occupations that may well match their disability-specific needs and limitations but not always their original occupational interests. For a sustainable return to work, this may be counterproductive as interest congruence predicts job satisfaction31, 32 and future occupational tenure.33

A comparison with the general population shows that the key demands of our participants’ occupations broadly reflect the O*NET requirements of college graduates’ typical occupations of the twenty-first century.20 This indicates a suitability of such rather cognitively demanding occupations for those individuals with SCI who have the intellectual capability to complete a higher education. Furthermore, it appears that the twenty-first labor market of developed countries with its increasing computerization of manual tasks and its growing service sector will favor cognitive, communicative and social skills over physical abilities.34, 35, 36 Although Kaye37 showed that individuals with mobility impairments in the United States are still underrepresented in cognitively and communicatively demanding occupations, such a future labor market would meet the disability-specific needs and limitations of persons with SCI and offer additional career opportunities for affected individuals.

Practical implications

Establishing a suitable vocational solution requires the determination of occupations whose demands and characteristics match an individual’s capabilities and characteristics.17 By providing general information on the key demands and characteristics across the most prevalent occupations of individuals with different SCI severities, our study supports the initial screening towards a first selection of well-matching occupations in vocational guidance. After completing such an initial screening, vocational counselors should evaluate on an individual level how well the demands and characteristics of these preselected occupations match with the client’s capabilities and characteristics. In doing so, counselors may rely on the set of specific O*NET descriptors (e.g., memorization abilities or writing skills) we extracted for each of our participants’ occupations. By specifying the particular demands and characteristics of an occupation, the O*NET descriptors identified in our study can serve as a basis for developing standardized job matching profiles for vocational guidance. Returning to a well-matched occupation after injury could help persons with SCI to realize their vocational potential, and also promote their job satisfaction, job performance and healthy employment,17 all of which are key indicators for a sustainable return to work. To truly establish the potential of O*NET-based job matching profiles, however, both their applicability in vocational guidance and their contribution toward a sustainable return to work should be tested in future research.

Study limitations

Our study is subject to a number of limitations. First, owing to the lack of a standardized occupational information system for Switzerland, we relied on the O*NET that was originally developed for the US labor market. Although the O*NET descriptors are deemed applicable across countries,38 some O*NET titles were not fully congruent with the occupational titles in Switzerland. This might have slightly affected the validity of the identified demands and characteristics in the context of the Swiss labor market.

Second, as our study was community-based, we relied on self-report questions on SCI level and degree instead of using the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI)22 for determining SCI severity. Although explanations were added to the question on SCI degree, it may be that the item was not sufficiently understandable for all participants, which could have led to incorrect answers. To address this potential source of error, we complemented the information on SCI severity by using walking ability as an additional, less error-prone stratification variable.

Third, our study focused on occupations of participants who were employed at the time of the survey. We neither considered occupations performed by the participants between SCI onset and time of the survey nor previous occupations of participants who were unemployed at the time of the survey. Including these occupations would have changed both the occupations’ prevalence and the average relevance values of their demands and characteristics. Moreover, it would have provided information on potentially less suitable occupations from which individuals dropped out. Future research should study the career trajectories of individuals with SCI to establish those occupations that are successfully performed and satisfying in the long term and those with an increased risk for dropouts.

Finally, the meaningfulness of the differences we found in the average relevance levels of the demands and characteristics across the occupations of individuals with different SCI severities and walking abilities is unclear. This is mostly because of the absence of practical experience with O*NET relevance values in the context of vocational guidance. Future research should thus start testing their practical significance.

Conclusion

The present study identified occupations performed by individuals with SCI living in Switzerland and established their demands and characteristics. While the demands and characteristics differed by SCI severity, our participants generally worked in cognitively and communicatively demanding occupations involving conventional work tasks and social relationships. The set of occupation-specific O*NET demands and characteristics we identified could inform the development of standardized job matching profiles and facilitate the determination of customized vocational solutions towards a more successful and sustainable return to work of individuals with SCI.

Data archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Yasuda S, Wehman P, Targett P, Cifu DX, West M . Return to work after spinal cord injury: a review of recent research. NeuroRehabilitation 2002; 17: 177–186.

Lidal IB, Huynh TK, Biering-Sørensen F . Return to work following spinal cord injury: a review. Disabil Rehabil 2007; 29: 1341–1375.

Reinhardt JD, Post MW, Fekete C, Trezzini B, Brinkhof MW, Group SS. Labor market integration of people with disabilities: results from the Swiss Spinal Cord Injury Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2016; 11: e0166955.

Trenaman L, Miller WC, Querée M, Escorpizo R . Modifiable and non-modifiable factors associated with employment outcomes following spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Spinal Cord Med 2015; 38: 422–431.

Ottomanelli L, Lind L . Review of critical factors related to employment after spinal cord injury: implications for research and vocational services. J Spinal Cord Med 2009; 32: 503–531.

Frieden L, Winnegar A . Opportunities for research to improve employment for people with spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord 2012; 50: 379–381.

Crewe NM . A 20-year longitudinal perspective on the vocational experiences of persons with spinal cord injury. Rehabil Counsel Bull 2000; 43: 122–133.

Dowler D, Batiste L, Whidden E . Accommodating workers with spinal cord injury. J Vocat Rehabil 1998; 10: 115–122.

Engel S, Murphy G, Athanasou J, Hickey L . Employment outcomes following spinal cord injury. Int J Rehabil Res 1998; 21: 223–230.

Meade MA, Lewis A, Jackson MN, Hess DW . Race, employment, and spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 1782–1792.

Castle R . An investigation into the employment and occupation of patients with a spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 1994; 32: 182–187.

Ottomanelli L, Goetz LL, Suris A, McGeough C, Sinnott PL, Toscano R et al. Effectiveness of supported employment for veterans with spinal cord injuries: results from a randomized multisite study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012; 93: 740–747.

Hwang M, Zebracki K, Vogel LC . Occupational characteristics of adults with pediatric-onset spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Injury Rehabil 2015; 21: 10–19.

Emmel A, Cosca T . The 2010 Standard Occupational Classification (SOC): a classification system gets an update. Occup Outlook Q 2010; 54: 13–19.

Sinden KE, Ginis KAM, SHAPE-SCI Research Group. Identifying occupational attributes of jobs performed after spinal cord injury: implications for vocational rehabilitation. Int J Rehabil Res 2013; 36: 196–204.

Staubli S, Schwegler U, Schmitt K, Trezzini B ICF-based process management in vocational rehabilitation for people with spinal cord injury. In Escorpizo R, Brage S, Homa D, Stucki G (eds). Handbook of Vocational Rehabilitation and Disability Evaluation. Springer: Berlin, 2015, pp 371–396.

Nützi M, Schwegler U, Medici L, Trezzini B . Job matching: an interdisciplinary scoping study with implications for vocational rehabilitation counseling. Rehabil Psychol 2017; 62: 45–68.

National Research Council A Database for a Changing Economy: Review of the Occupational Information Network (O* NET). National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA. 2010.

Peterson NG, Borman WC, Mumford MD, Jeannerete PR, Fleishman EA . An Occupational Information System for the 21st Century: The Development of O*NET. American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA. 1999.

Burrus J, Jackson T, Xi N, Steinberg J . Identifying the Most Important 21st Century Workforce Competencies: An Analysis of the Occupational Information Network (O* NET), Report no.: RR-13-21. Educational Testing Service: Princeton, NJ, USA. 2013.

Post MW, Brinkhof MW, von Elm E, Boldt C, Brach M, Fekete C et al. Design of the Swiss Spinal Cord Injury Cohort Study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2011; 90: S5–S16.

Brinkhof MW, Fekete C, Chamberlain JD, Post MW, Gemperli A, SwiSCI Study Group. Swiss National Community Survey of Functioning After Spinal Cord Injury: protocol, characteristics of participants and determinants of non-response. J Rehabil Med 2016; 48: 120–130.

Itzkovich M, Gelernter I, Biering-Sorensen F, Weeks C, Laramee M, Craven B et al. The Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM) version III: reliability and validity in a multi-center international study. Disabil Rehabil 2007; 29: 1926–1933.

R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria,. 2016.

International Labor Organization. International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-08), 2008. Available at: http://www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/stat/isco/isco08/index.htm. Accessed on 7 February 17.

Federal Statistical OfficeSwiss Die Schweizerische Arbeitskräfteerhebung ab 2010. Konzepte-Methodische Grundlagen-Praktische Ausführung: Switzerland, 2012.

Mumford MD, Zaccaro SJ, Harding FD, Jacobs TO, Fleishman EA . Leadership skills for a changing world: Solving complex social problems. Leadership Q 2000; 11: 11–35.

Schwegler U, Nützi M, Marti A, Trezzini B Comparison of job types performed before and after sustaining a spinal cord injury: A study from Switzerland. Poster presented at the 14th Congress of the European Forum for Research in Rehabilitation (EFRR) (Glasgow, Scotland, 2017).

Marti A, Reinhardt J, Graf S, Escorpizo R, Post M . To work or not to work: labour market participation of people with spinal cord injury living in Switzerland. Spinal Cord 2012; 50: 521–526.

Krause JS, Saunders LL, Staten D, Rohe DE . Vocational interests after recent spinal cord injury: comparisons related to sex and race. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011; 92: 626–631.

Mount MK, Muchinsky PM . Person–environment congruence and employee job satisfaction: a test of Holland's theory. J Vocat Behav 1978; 13: 84–100.

Wille B, Tracey TJ, Feys M, De Fruyt F . A longitudinal and multi-method examination of interest–occupation congruence within and across time. J Vocat Behav 2014; 84: 59–73.

Meir EI, Esformes Y, Friedland N . Congruence and differentiation as predictors of worker's occupational stability and job performance. J Career Assess 1994; 2: 40–54.

European Commission.Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions—A New Skills Agenda for Europe. Brussels, Publications Office of the European Union, 2016.

Notter P, Arnold C, von Erlach E, Hertig P . Lesen und Rechnen im Alltag—Grundkompetenzen von Erwachsenen in der Schweiz. Nationaler Bericht zu der Erhebung «Adult Literacy & Lifeskills Survey». Bundesamt für Statistik (BFS): Neuchâtel, Switzerland. 2006.

Rammstedt B Grundlegende Kompetenzen Erwachsener im internationalen Vergleich: Ergebnisse von PIAAC 2012. Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2013.

Kaye HS . Stuck at the bottom rung: occupational characteristics of workers with disabilities. J Occup Rehabil 2009; 19: 115.

Taylor PJ, LI W-D, Shi K, Borman WC . The transportability of job information across countries. Personnel Psychol 2008; 61: 69–111.

Acknowledgements

The present study was conducted as part of a PhD thesis funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant No 153033). This study has been financed in the framework of the Swiss Spinal Cord Injury Cohort Study (SwiSCI, http://www.swisci.ch), supported by the Swiss Paraplegic Foundation. The members of the SwiSCI Steering Committee are: Xavier Jordan, Bertrand Léger (Clinique Romande de Réadaptation, Sion, Switzerland); Michael Baumberger, Hans Peter Gmünder (Swiss Paraplegic Center, Nottwil, Switzerland); Armin Curt, Martin Schubert (University Clinic Balgrist, Zürich, Switzerland); Margret Hund-Georgiadis, Kerstin Hug (REHAB Basel, Basel, Switzerland); Thomas Troger (Swiss Paraplegic Association, Nottwil); Daniel Joggi (Swiss Paraplegic Foundation, Nottwil); Hardy Landolt (Representative of persons with SCI, Glarus, Switzerland); Nadja Münzel (Parahelp, Nottwil); Mirjam Brach, Gerold Stucki (Swiss Paraplegic Research, Nottwil); Martin Brinkhof (SwiSCI Study Center at Swiss Paraplegic Research, Nottwil).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on the Spinal Cord website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nützi, M., Trezzini, B., Ronca, E. et al. Key demands and characteristics of occupations performed by individuals with spinal cord injury living in Switzerland. Spinal Cord 55, 1051–1060 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.84

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.84

This article is cited by

-

Promoting factors and barriers to participation in working life for people with spinal cord injury

Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology (2020)