Abstract

Study design:

Descriptive cross-sectional study.

Objectives:

To investigate the relationship between perceived social support and depression and to evaluate the role of family, friends and other caregivers in the perception of social support in Iranian individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI).

Setting:

Brain and Spinal Cord Injury Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Methods:

Social support was evaluated using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support questionnaire, which gauges perceptions of support from family, friends and ‘important persons’. The presence and severity of depression were assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II-PERSIAN)—a 21-item multiple-choice questionnaire.

Results:

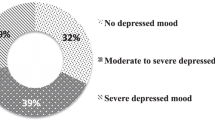

A total of 140 individuals with SCI were enrolled in the study. The average age of the participants was 29.4±7.9 years; the mean duration of injury was 46.3±46.5 months and most patients were male (72%). Social support and all subscales of social support were numerically greater in males; however, this difference was not statistically significant. The subcategory of friends’ support in men was 17.9±7.9 compared to 14.6±8.0 in women (P=0.04). The self-reported social support score (r=−0.387, P<0.001) and subscales of social support, including family (r=−0.174, P=0.045), friends (r=−0.356, P<0.001) and important persons (r=−0.373, P<0.001), were all negatively correlated with depression.

Conclusion:

Higher self-reported perception of social support appears to be associated with lower levels of depression in individuals with SCI. SCI care providers should consider the relationship between social support and depression in their continuing care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) encounter many difficulties in their everyday life including functional limitations, secondary conditions, medical complications and impaired quality of life.1, 2 Adjusting to the consequences of a neurologic injury can be a major challenge. Social support is important for the adjustment process in individuals with SCI.

Social support is generally defined as the assistance provided by others, which fosters a belief that the individual is loved, respected and cared for. Previous studies have suggested a positive influence of social support on health,3, 4, 5 life satisfaction6, 7 and even mortality in patients with chronic diseases.8, 9 Social support also helps patients to cope with the negative effects of stress.6 Different types of social support including operational, educational and emotional are often provided by different sources, such as family and friends. A systematic review of individuals with SCI found that social support was strongly associated with better physical and mental health, lower pain, more effective coping mechanisms, better adjustment to the disability and higher satisfaction and quality of life.10

The association between social support and depression has been investigated in a number of studies. A report by Grav et al.11 assessed the association between two types of perceived social support, tangible and emotional, and levels of depression among a sample of the general population from Norway. They employed the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale to evaluate the level of depression among participants. The study findings demonstrated that there was a strong relationship between self-reported perceptions of support and level of depression. Furthermore, a significant gender difference was found with respect to the effects of emotional and tangible support among older individuals with lower perceived social support. Specifically, depression occurred more commonly among women lacking emotional support, whereas a higher prevalence of depression existed among men wanting tangible support.11 A report from the United Kingdom by Beedie et al.12 found strong associations between the quality and quantity of social support and the level of depression or hopelessness among individuals with SCI. In another study by Huang et al.13 conducted in Taiwan, the effects of several factors on depressive symptoms were evaluated in an adult population with SCI; similarly, the results demonstrated that the level of perceived social support was a strong predictor of depressive symptoms. In another study, the association among social support, attachment style, resilience and depression was investigated in adults with complete or incomplete SCI undergoing a comprehensive rehabilitation program; the results indicated that higher levels of attachment avoidance were associated with lower perceived social support and lower perceived resilience. Moreover, attachment anxiety was significantly associated with depression.14 In another report from Italy, relationship quality, perceived social support and health-related quality of life were evaluated in 43 individuals with SCI. The results underscored the significant association between relationship quality and social support.15

The association between social support and depression has been well studied. However, most of the studies were from the Occident, and literature evidence from Middle East countries is very scarce. The authors of the present report shared a hypothesis that unique cultural aspects of Iranian population regarding gender roles and gender role identification could have a significant role on the level and source of social support and its association with depression. Gender role, a concept that is generally defined as a set of behaviors, attitudes and personality characteristics in a particular culture, has been strongly influenced by social values and norms.16, 17 The attitudes of Iranian people toward the roles and responsibilities of women and men are significantly different compared to those in Western countries, particularly among people from suburban and rural areas. Furthermore, the gradual modernizing process as well as urbanization faced the Iranian women with unparalleled stressors. They have to have their traditional role as a housewife and house manager. On the other hand, they are confronted with conflicting workplace roles.18, 19 Moreover, the gender roles in countries of the Eastern Mediterranean region are highly polarized with women facing many inequalities regarding socioeconomic indicators, income, social status and rank, as well as lack of autonomy.20

The impact of social and spousal support on marital satisfaction was addressed in a study of 653 Iranian medical staff; the results demonstrated that spousal support provided by the women for their husbands was significantly higher than social support provided by the men for their wives. Moreover, the role of spousal support in marital satisfaction was more important for women in comparison to their husbands.21

The objective of this study was to investigate the association of perceived social support and its subscales (family, friends and important persons) with depression, injury characteristics, level of education, access to appropriate facilities and gender in Iranian individuals with SCI.

Methods

Design

This cross-sectional study was a part of a large project,17, 22 which was conducted at the Brain and Spinal Cord Injury Research Center at the Imam Khomeini Hospital Complex, Tehran, Iran from 2012 to 2013. The sample for these studies was the same. One part of this project evaluated depression and its association with injury characteristics, demographic and socioeconomic determinants of depression.17 Another part evaluated pain and associations between pain and social support. We evaluated pain and the relationship between pain and demographic (age, gender), level of injury (tetraplegia or paraplegia), completeness of injury, cause of injury, education level, marital status and social support in individuals with SCI. We reported the correlation of pain and social support.22 In this study, we focus on social supports and their associations with depression.

Participants

The participants included individuals with SCI referred for outpatient rehabilitation to the clinic of the Brain and Spinal Cord Injury Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The Brain and Spinal Cord Injury Research center is a referral center from all parts of Iran. Individuals with SCI aged 18 years and older, and those using any type of wheelchair, who were willing and able to provide verbal and written informed consent, were included in the study. The study protocol was in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki23 and was approved by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences ethics committee.

Procedure

Following enrollment, the depression and perceived social support measures were described to individuals with SCI by the principal investigator. Because some individuals were either illiterate or lacked the physical capability to complete a written questionnaire, the questions were asked verbally and all individuals’ responses were recorded by the investigators. Also, because some responses may be affected by the presence of others, the perceived social support scale was completed by participants without their family members in attendance. Patient demographics including age, gender, years of education and duration of disability were documented. The accessibility of appropriate facilities for transportation, urination and prevention of SCI complications was also assessed as an indicator of economic status.17

Perceived social support

Self-reported perceptions of social support were assessed by the Persian version of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support24 questionnaire, which can be used to measure the patient-reported perception of support from family, friends and important persons and scored to indicate a global perception of support. We assessed perceived social support, not actual social support. The items are rated on a Likert scale from 1 to 7 (corresponding to ‘very strongly disagree’ and ‘very strongly agree’, respectively); hence the global score ranges from 12 to 84, and the range of the subscores for family, friends and important persons is 4–28. The reliability of the scale was evaluated for internal consistency (Cronbach α=0.857). Also Cronbach’s alpha of the subscales of family (0.679), friends (0.909) and important persons (0.720) was calculated. The internal validity of the questionnaires was achieved through consultation with a group of experts over several sessions.

Depression

The presence and severity of depression were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II-PERSIAN), a 21-item multiple-choice questionnaire.25 Content Validity, or the applicability of this questionnaire to the study population, was evaluated by an expert panel, and the reliability (internal consistency) was determined using Cronbach's coefficient-α (0.861).

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS software package version 18 (IBM, New York, NY, USA). A one-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to estimate the distribution of data. To compare continuous variables between two categorical variables, we used t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test, and, between three or more categorical variables (such as having appropriate facilities and education level), we used analysis of variance or Kruskal–Wallis test when appropriate. Parametric tests were used when the continuous variables were normally distributed and nonparametric tests were used when they were not normally distributed. Nonparametric tests were also used with categorical and ordinal data. χ2- or Fisher's exact tests were performed to evaluate the relationship among categorical variables between groups as indicated. The correlation of continuous variables (perceived social support and its subscales with BDI score, age at time of SCI, current age, duration of SCI and number of children) was evaluated with a Pearson coefficient. We used linear regression model to adjust for the effect of independent variables (age, level of injury, gender, marital status, having living facility as an indicator of economic status, education level and depression) on the dependent variable (social support). Continuous variables were presented as mean±s.d. A significance level of P⩽0.05 was chosen before the data collection commenced.

Results

The response rate was 97% (140 out of 144). The most common cause of SCI was motor vehicle crash, which occurred in 92 (69%) cases, followed by falling in 27 (20%) cases. The sociodemographic and injury characteristics are further described in Table 1.

Only the mean subscale of perceived friends' support in men was significantly higher than that in women (P=0.04) (Table 2). There were no statistically significant differences in perceived social support score or any subscales with respect to the level of injury, completeness, marital status, having children, education level or having appropriate facilities (Table 3). There also were no significant correlations between perceived social support and its subscales with respect to current age, age at time of SCI, duration of SCI or the number of children.

All individuals with paraplegia and tetraplegia required care and named someone who cared for them (Table 1). Out of the 57 single men, 40 (70%) were cared for by their parents and 17 (30%) by other family members. Three (5%) of these 17 chose to be cared for by a wife, and one (2%) preferred a nurse. Twenty-seven of 43 married men (63%) were taken care of by their wives, four (9%) by their parents and 12 (28%) by other family members. Out of the 11 single women, seven (64%) were cared for by their parents and four (36%) by other family members. Seven married women (27%) were cared for by their husbands, eight (31%) by their parents, nine (35%) by other member family members and two (8%) by a nurse.

The perceived social support score and all subcategories demonstrated negative correlations with the Beck depression scores; that is, higher levels of perceived social support were associated with lower Beck depression scores (Table 4).

Linear regression of social support as the dependent variable and age, level of injury, gender, marital status, having living facility as an indicator of economic status, education level and depression (Beck score) as independent variables showed that having appropriate living facility had significant positive relationship with social support (P=0.019), and depression (Beck score) had a significant negative relationship with social support (P<0.001; Table 5).

Discussion

These results demonstrate that among individuals with SCI, higher scores of perceived social support were associated with lower levels of depression. In addition, men reported a significantly higher level of perceived social support from friends compared to women.

Perceived social support among men was higher but not significantly different from that of women with SCI. In contrast, Jensen et al.26 concluded that male gender was associated with lower levels of social support. One possible explanation for the differences between these two studies involves cultural differences. In Iran, males generally experience greater levels of social support than females do. In our study, married men reported being taken care of by their spouse more often than married women (63 vs 27%).

In a study by Tramonti et al.,15 the association between relationship quality and perceived social support was investigated in 43 individuals with SCI; their findings underscore a significant impact of marital satisfaction on social support and indicated that the role of receiving support from spouse and other family members was more important than the friends’ support. Furthermore, there was a positive meaningful association between relationship quality and different aspects of health-related quality of life. In contrast, no correlation was noted between health-related quality of life and spousal support.15

In addition, women with SCI may be more likely than men to be embarrassed about their condition and avoid seeking out social support or engaging in social events. May be women with SCI have more limitations in their social interactions and contact with loved ones and avoid seeking out support from friends and relatives; this, in turn, may serve to increase depression.17 Reduced contact with friends is a major concern among individuals with SCI in other societies27, 28

Social problems in individuals with SCI are associated with financial difficulties due to unemployment, higher costs of living, and struggles with transportation, residential modifications, education and marriage.16 The family’s economic dependency obliges men to spend more time at work, away from home and consequently they have less time to take care of their wives. One way to address these issues is to provide financial aid for their families. For example, if the financial stress on the husbands of women with SCI could be reduced, they may be able to provide more emotional support to their wives. Nonetheless, any underlying reasons for lower levels of perceived social support among Iranian women with SCI should be explored in future studies.

In a systematic review by Muller et al., a comprehensive search was conducted to find studies in which the relationship between social support and different aspects of health, functioning and quality of life was investigated; the findings indicated that social support was positively related to physical and mental health, life satisfaction, subjective well-being, quality of life, coping adjustment, productivity and participation, and had a negative relationship with pain, health problems, disability-related problems among individuals with SCI.10 This study demonstrated that higher levels of perceived social support were associated with lower levels of depression similar to other studies.12, 26, 29, 30, 31 In contrast, however, in a recently published study, Muller et al.32 demonstrated no significant association between social support and depression.

A number of studies have investigated the role of social support from friends among individuals with SCI in different countries. In a study conducted in the USA, women reported greater support than men, especially from friends, which is contrary to our results.26 The authors mentioned the influence of social networks or media in their community, which exists to a lesser degree in our society, although in recent years social networks have increased here as well. Perceived support from friends was negatively associated with depression, and this relationship was not different across genders.26

Limitations

Of course this study was not without inherent biases. Given the location of our clinic in the capital, relatively poor individuals and individuals with limited education or those with higher levels of disability are unlikely to come from rural areas, and consequently there may be 'some' selection bias. While the gender discrepancy with other studies could be cultural, similar studies in other low-income countries are recommended to determine whether there is greater friend support in male individuals with SCI than in females. Although our study did not find significant differences regarding perceived social support between males and females, these results were limited by small sample sizes. Further, income or financial status could not be measured in this study because individuals with SCI may have self-reported no income due to unemployment or under-reported their income for reasons of secondary gain. Therefore, it is recommended that larger studies be conducted among diverse populations to verify our findings.

Conclusion

Higher self-reported social support is associated with lower levels of depression in individuals with SCI. Men reported a significantly higher level of perceived support from friends compared to women. Rehabilitation strategies to improve the depression levels among women with SCI should consider addressing social support from friends. This study is unique as it demonstrates not only an association between greater social support and lower depression but also the significant role of friends in reducing depression in individuals with SCI. Further studies are recommended to determine whether interventions that improve perceived social support will decrease depression among individuals with SCI. SCI care providers should consider the close association between social support and depression in their continuing care.

References

Post MW, de Witte LP, van Asbeck FW, van Dijk AJ, Schrijvers AJ . Predictors of health status and life satisfaction in spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 79: 395–401.

Chiodo AE, Scelza WM, Kirshblum SC, Wuermser LA, Ho CH, Priebe MM . Spinal cord injury medicine. 5. Long-term medical issues and health maintenance. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 88 (3 Suppl 1): S76–S83.

Steptoe A, Lundwall K, Cropley M . Gender, family structure and cardiovascular activity during the working day and evening. Soc Sci Med 2000; 50: 531–539.

Ali SM, Merlo J, Rosvall M, Lithman T, Lindstrom M . Social capital, the miniaturisation of community, traditionalism and first time acute myocardial infarction: a prospective cohort study in southern Sweden. Soc Sci Med 2006; 63: 2204–2217.

Norbeck JS . Types and sources of social support for managing job stress in critical care nursing. Nurs Res 1985; 34: 225–230.

Cohen S, Wills TA . Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull 1985; 98: 310–357.

Helgeson VS . Social support and quality of life. Qual Life Res 2003; 12 (Suppl 1): 25–31.

Berkman LF, Syme SL . Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am J Epidemiol 1979; 109: 186–204.

Gruenewald TL, Karlamangla AS, Greendale GA, Singer BH, Seeman TE . Feelings of usefulness to others, disability, and mortality in older adults: the MacArthur study of successful aging. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2007; 62: P28–P37.

Muller R, Peter C, Cieza A, Geyh S . The role of social support and social skills in people with spinal cord injury—a systematic review of the literature. Spinal Cord 2012; 50: 94–106.

Grav S, Hellzen O, Romild U, Stordal E . Association between social support and depression in the general population: the HUNT study, a cross-sectional survey. J Clin Nurs 2012; 21: 111–120.

Beedie A, Kennedy P . Quality of social support predicts hopelessness and depression post spinal cord injury. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2002; 9: 227.

Huang CY, Chen WK, Lu CY, Tsai CC, Lai HL, Lin HY et al. Mediating effects of social support and self-concept on depressive symptoms in adults with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2015; 53: 413–416.

Dodd Z, Driver S, Warren AM, Riggs S, Clark M . Effects of adult romantic attachment and social support on resilience and depression in individuals with spinal cord injuries. Top Spinal Cord Injury Rehabil 2015; 21: 156–165.

Tramonti F, Gerini A, Stampacchia G . Relationship quality and perceived social support in persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2015; 53: 120–124.

Khazaeipour Z, Norouzi-Javidan A, Kaveh M, Khanzadeh Mehrabani F, Kazazi E, Emami-Razavi SH . Psychosocial outcomes following spinal cord injury in Iran. J Spinal Cord Med 2014; 37: 338–345.

Khazaeipour Z, Taheri-Otaghsara SM, Naghdi M . Depression following spinal cord injury: its relationship to demographic and socioeconomic indicators. Top Spinal Cord Injury Rehabil 2015; 21: 149–155.

Eloul L, Ambusaidi A, Al-Adawi S . Silent epidemic of depression in women in the middle east and north africa region: emerging tribulation or fallacy? Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2009; 9: 5–15.

Saliba M, Zurayk H . Expanding concern for women's health in developing countries: the case of the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Women's Health Issues 2010; 20: 171–177.

Gender Disparities in Mental Health: World Health Organization (WHO); 2006.

Rostami A, Ghazinour M, Richter J . Marital satisfaction: the differential impact of social support dependent on situation and gender in medical staff in Iran. Glob J Health Sci 2013; 5: 151–164.

Khazaeipour Z, Ahmadipour E, Rahimi-Movaghar V, Ahmadipour F, Vaccaro AR, Babakhani B . Association of pain, social support and socioeconomic indicators in patients with spinal cord injury in Iran. Spinal Cord 2017; 55: 180–186.

Declaration of Helsinki.. Recommendations guiding doctors in clinical research. Adopted by the World Medical Association in 1964. Wis Med J 1967; 66: 25–26.

Bagherian-Sararoudi R, Hajian A, Ehsan HB, Sarafraz MR, Zimet GD . Psychometric properties of the persian version of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in iran. Int J Prev Med 2013; 4: 1277–1281.

Ghassemzadeh H, Mojtabai R, Karamghadiri N, Ebrahimkhani N . Psychometric properties of aPersian-language version of the Beck Depression Inventory—Second edition: BDI-II-PERSIAN. Depress Anxiety 2005; 21: 185–192.

Jensen MP, Smith AE, Bombardier CH, Yorkston KM, Miro J, Molton IR . Social support, depression, and physical disability: age and diagnostic group effects. Disabil Health J 2014; 7: 164–172.

Songhuai L, Olver L, Jianjun L, Kennedy P, Genlin L, Duff J et al. A comparative review of life satisfaction, quality of life and mood between Chinese and British people with tetraplegia. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 82–86.

Tasiemski T, Kennedy P, Gardner BP, Taylor N . The association of sports and physical recreation with life satisfaction in a community sample of people with spinal cord injuries. NeuroRehabilitation 2005; 20: 253–265.

Pang MY, Eng JJ, Lin KH, Tang PF, Hung C, Wang YH . Association of depression and pain interference with disease-management self-efficacy in community-dwelling individuals with spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Med 2009; 41: 1068–1073.

Elliott TR, Herrick SM, Witty TE, Godshall F, Spruell M . Social support and depression following spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol 1992; 37: 37–48.

Morlett-Paredes A, Perrin PB, Olivera SL, Rogers HL, Perdomo JL, Arango JA et al. With a little help from my friends: social support and mental health in SCI caregivers from Neiva, Colombia. NeuroRehabilitation 2014; 35: 841–849.

Muller R, Peter C, Cieza A, Post MW, Van Leeuwen CM, Werner CS et al. Social skills: a resource for more social support, lower depression levels, higher quality of life, and participation in individuals with spinal cord injury? Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015; 96: 447–455.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the staff of Brain and Spinal Cord Injury Research Center, Neuroscience institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. We acknowledge and express our gratitude to Alireza Salehi-Nejad for reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khazaeipour, Z., Hajiaghababaei, M., Mirminachi, B. et al. Social support and its association with depression, gender and socioeconomic indicators in individuals with spinal cord injury in Iran. Spinal Cord 55, 1039–1044 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.80

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.80

This article is cited by

-

Exploring Iranian individual’s perception toward divorce after disability related to spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2020)