Abstract

Objectives:

The objective of this study was to determine the national hospitalization burden of spinal cord injuries (SCIs) among adults in the United States. Factors predicting hospitalization outcomes including length of stay (LOS), total charges and discharge disposition of death were identified.

Setting:

The study was conducted in the United States.

Methods:

The 2009 Health Care Utilization Project Nationwide Inpatient Sample (HCUP–NIS) data were used in this study. Hospitalization outcomes among individuals with SCI were compared with a control group of individuals without SCI. Predictors of LOS, total charges and discharge disposition of death for SCI-related hospitalizations were determined using regression techniques.

Results:

In 2009, there were a total of 11 848 hospitalizations because of SCI in the United States. Hospitalizations because of SCIs had 2.5 times higher LOS (12.37 (±0.51) versus 4.93 (±0.09), P<0.0001) and 4 times higher average charges ($142 366 (±$7430.51) versus $35 011 (±$1048.88), P<0.0001) as compared with those for the control group. The total national charge attributable to SCI-related hospitalizations was approximately $1.69 billion in 2009. Percentage of hospitalizations with discharge disposition of death was significantly higher among individuals with SCI as compared with those without SCI (5.77 versus 2.27%, P<0.0001). Different patient and hospital characteristics predicted LOS, total charges and discharge disposition of death for SCI-related hospitalizations.

Conclusions:

There is considerable inpatient burden associated with SCI in the United States. Inpatient LOS, charges and percentage of hospitalizations with discharge disposition of death were higher among individuals with SCI as compared with those without SCI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a severely debilitating condition that is characterized by mobility limitations, excessive dependence on others and a diminished health-related quality of life.1 Vehicular accidents, falls and violence are the top three causes of SCIs, and together they account for >80% of injuries.2 The incidence of SCIs in the United States has been estimated to be roughly 40 cases per million population or 12 000 cases per year.2 Males are almost four times more likely to sustain SCIs than females.2 SCIs are associated with a significant economic burden. The total annual costs attributable to SCIs are ∼$9.7 billion in the United States, including $2.6 billion in lost productivity costs.3

Hospitalization is a critical component of treatment for SCIs. Nearly all patients who incur a SCI and survive the initial trauma undergo hospitalization for stabilization of the injury and prevention of immediate complications.4 Rehospitalizations because of complications of SCI are also common among patients with SCI.5 Given these facts, it is not surprising that hospitalizations account for a large proportion of the medical costs associated with SCIs.5 An understanding of the hospitalization burden is important for the purpose of resource allocation. Some studies in the past have investigated the inpatient utilization associated with SCIs.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 When examining the cost of SCI using a population-based registry in the state of Colorado, Johnson et al.8 found the average initial hospitalization charge following injury to be $134 383.8 In their analysis involving patients treated in three Veteran Health Administration SCIy centers, French et al.9 found the average hospitalization costs associated with SCIs to be between $19 994 and $52 489.9 Although these studies provide useful information, all were conducted in specific hospital settings in certain geographical locations and were not nationally representative. Furthermore, most of these studies present data that are more than two decades old6, 7, 8 and may not be applicable in the current context. Lastly, information concerning the effect of hospital characteristics and important patient characteristics including income and health insurance on SCI-related hospitalization outcomes is currently unavailable.

In this study, we determined the hospitalization burden associated with SCIs in terms of inpatient utilization and charges associated with the condition using nationally representative inpatient discharge data from the Health Care Utilization Project Nationwide Inpatient Sample (HCUP–NIS) database. Patient-, hospital- and discharge-level characteristics of hospitalizations associated with SCI were compared with hospitalizations for causes other than SCI. In addition, patient-, hospital- and discharge-level characteristics predicting length of stay (LOS), total charges and discharge disposition of death were determined.

Materials and methods

Data source

The 2009 HCUP–NIS data were used for the purpose of this study. Established as a federal–state–industry partnership and sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the HCUP–NIS is the largest all-payer inpatient national database in the United States. The 2009 HCUP-NIS database consisted of roughly 8 million discharge records obtained from a 20% stratified sample of 1040 hospitals from 44 states. The NIS is a discharge-level data with each observation representing one hospitalization. The NIS data set does not contain direct patient identifiers. Each observation in the NIS is associated with a stratum-specific discharge weight in order to enable generalization of the findings to the entire nation. The discharge weights are determined as a ratio of the total number of discharges in each stratum (obtained from the American Hospital Association data) to the total number of NIS discharges in that stratum. According to federal regulations, Institutional Review Board approval is not required for research using the HCUP-NIS database, as it is a de-identified publically available data set.11

Study design

The present study used a cross-sectional case–control design. Patients <18 years of age were excluded, as SCIs are not common among children.12 From the remaining data, we identified records with a primary diagnosis of a SCI (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes 806.xx and 952.xx), and classified them as cases. The control group of hospitalizations consisted of records without any listed diagnosis of SCI. Each SCI-related hospitalization (case) was matched to two control hospitalizations based on age and gender using a greedy match algorithm.

Measures

The patient-level variables compared between cases and controls included age, gender, income and type of insurance. Hospital-level variables such as hospital size, location, region and teaching status were compared between cases and controls. The discharge-level variables compared between cases and controls included discharge disposition, LOS, total hospital charges and number of diagnoses.

Statistical analysis

Considering the complex sampling design of the HCUP-NIS data, PROC SURVEY procedures in SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) were used for all study analyses. PROC SURVEYFREQ was used to compare frequencies and percentages for the categorical variables. PROC SURVEYMEANS and PROC SURVEYREG were used to compare means across continuous variables. Predictors of LOS and total charges were determined using the PROC SURVEYREG procedure, whereas predictors of discharge disposition of death were determined using PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC. All results reported are weighted unless noted otherwise.

Results

The patient-, hospital- and discharge-level characteristics of individuals with and without SCI are reported in Table 1. Most of the individuals hospitalized for SCIs were <60 years of age (38.51%) and males (69.53%). Some of the common comorbid illnesses among individuals with SCI were hypertension, lung disorders and nondependent abuse of drugs, whereas hypertension, disorders of fluid electrolyte and acid–base balance and nondependent abuse of drugs were the leading diagnoses among individuals without SCI (not mentioned in the table). Hospitalizations for SCIs were significantly more likely to have occurred in small-sized (P<0.0001), urban (P=0.0009) and teaching hospitals (P<0.0001) as compared with hospitalizations without a diagnosis of SCI. Greater proportion of hospitalizations for SCIs occurred in individuals with private insurance (P<0.0001). The percentage of hospitalizations occurring in trauma centers was greater in hospitalizations for SCI as compared with hospitalizations for other reasons (P<0.0001). Greater proportion of hospitalizations for SCI led to transfer to other facilities (P<0.0001). Hospitalizations for SCIs had nearly 2.5 times longer LOS, 4 times higher charges and 2.5 times higher percentage of hospitalizations with discharge disposition of death as compared with hospitalizations without a diagnosis of SCI (P<0.0001).

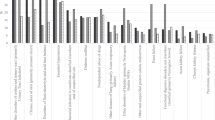

Table 2 reports the results of the multiple regression analysis conducted to determine the predictors of longer LOS associated with hospitalizations for SCI. Patients aged 18–29 years (P<0.0001), 30–39 years (P<0.0001), 40–49 years (P<0.0001) and 50–59 years (P<0.0001) had significantly longer LOS as compared with individuals aged >60 years. Females had shorter LOS as compared with males (P=0.0019). Hospitalizations in large-sized hospitals had longer LOS as compared with small-sized hospitals (P=0.0169). Hospitals in rural region and hospitals with nonteaching status had shorter LOS as compared with hospitals in urban region (P=0.0006) and hospitals with teaching status respectively (P=0.0010). The LOS was longer in patients who were discharged to other health facilities as compared with those who had a routine discharge (P=0.0002). The LOS increased with the number of diagnoses on the record (P<0.0001).

Table 3 presents the results of the multiple regression analysis conducted to determine the predictors of higher total hospitalization charges for SCIs. Patients aged 18–29 years (P<0.0001), 30–39 years (P<0.0001), 40–49 years (P<0.0001) and 50–59 years (P=0.0057) had significantly higher total charges as compared with patients aged >60 years. Hospitalizations among individuals with private insurance had higher total charges as compared with those with self-pay (P=0.0015). Hospitalizations in medium- (P=0.0305) and large-sized hospitals (P=0.0237) had higher total charges as compared with small-sized hospitals. Hospitalizations in rural region and hospitals with nonteaching status had lower total hospitalization charges as compared with hospitalizations in urban region (P=0.0138) and hospitals with teaching status respectively (P=0.0455). The total hospitalization charges were higher among patients who were discharged to other health facilities as compared with those who had a routine discharge (P<0.0001). Hospitalizations with higher number of diagnoses on record were associated with higher total charges (P<0.0001). Hospitalization charges increased with LOS (P<0.0001).

Table 4 presents the results of the logistic regression analysis conducted to determine the predictors of discharge disposition of death in hospitalizations for SCIs. Patients aged 18–29 years (P<0.0001), 30–39 years (P=0.0010), 40–49 years (P=0.0001) and 50–59 years (P=0.0002) had lower odds of discharge disposition of death as compared with patients aged >60 years. Females had 35% lower odds of discharge disposition of death as compared with males (P=0.0455). Patients with private insurance had lower odds of discharge disposition of death as compared with patients with ‘self-pay’ hospitalizations (P=0.0201). Higher number of diagnoses on record was associated with increased likelihood of discharge disposition of death (P=0.0011).

Discussion

The current study determined the national inpatient burden associated with SCIs in the United States using a nationally representative database. Predictors of LOS, total hospitalization charges and discharge disposition of death associated with SCI-related hospitalizations were identified. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to present national estimates for hospitalization charges, LOS and other outcomes among patients with SCIs.

A total of 11 848 weighted hospitalizations occurred nationally with a primary diagnosis of SCI in 2009. Most of the hospitalizations for SCIs occurred in individuals >60 years of age. This finding is in contrast with previous studies that have reported that traumatic SCIs are more common in younger individuals.13, 14 However, recent studies have reported increasing incidence rates of SCIs in the elderly over the past few decades.2, 15 It is possible that, in our study, elderly individuals had more number of rehospitalizations post the initial treatment of traumatic SCIs. Significant differences were observed in the hospital- and discharge-level characteristics in hospitalizations with and without SCIs. Significantly lower proportion of SCI-related hospitalizations occurred in rural as compared with urban areas. This was a surprising finding, as the incidence rates of traumatic injuries are higher in rural areas.16 A plausible reason for this finding may be that there is a shortage of well-equipped hospitals and skilled physicians required to meet the complex medical needs of patients with SCIs in rural areas17 that may make it necessary for some patients with these injuries in rural areas to be transferred to urban hospitals for treatment. Greater proportion of patients with SCIs were admitted to teaching hospitals as compared with patients hospitalized for other conditions. This may be explained by the fact that teaching hospitals are better equipped with sophisticated technology needed to treat complex conditions such as SCIs as compared with nonteaching hospitals.18 Greater proportion of hospitalizations for SCIs occurred in trauma centers as compared with hospitalizations for other reasons. This was an expected finding as trauma centers are specially equipped for the treatment of traumatic injuries. For patients with SCIs, roughly 54% of the discharges resulted in transfer to other facilities and 27% of the discharges were routine, whereas for patients hospitalized for other reasons, more than two-thirds of the discharges were routine. The high percentage of discharges resulting in transfer to other facilities in hospitalizations for SCIs may be because of the fact that hospitalizations for the treatment of traumatic SCIs are usually followed by rehabilitation19 and hence may involve transfer to a rehabilitation center. In our study, hospitalizations for SCI could have been for the initial treatment of traumatic SCIs or follow-up hospitalizations post the initial treatment of SCIs. The follow-up hospitalizations for the treatment of SCIs could have contributed to the substantial number of routine discharges in SCI-related hospitalizations observed in our study.

The mean LOS in patients with SCI was more than twice as long as the LOS among patients without these injuries. Injuries of spinal cord are extreme medical events that require extensive health-care resource utilization. The longer LOS observed in our study signifies the complexity of stabilizing and/or maintaining the health of these patients. The average LOS for patients with SCI was ∼12 days, which is consistent with those reported by the National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center (NSCISC).2 The mean total charge per hospitalization for a SCI was $142 366, which is more than four times the charge for non-SCI hospitalizations. Several studies have estimated the costs of hospitalization for SCIs in the past.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Differences in study settings and methodology make it difficult to present adequate comparisons with prior studies. Nonetheless, some general patterns observed in our study were found to be consistent with earlier such studies. For example, Johnson et al.8 found the initial hospitalization and rehabilitation charges to be ∼$134 000 among patients with SCI.8 The NSCISC estimated the costs of initial hospitalization because of SCI to be around $140 000.10 Our charge estimates are similar to those reported in these studies. The total national inpatient charge attributable to SCIs in 2009 was $1.69 billion. All these studies, including ours, reflect the considerable economic burden placed by SCIs on the health-care system.

Regression analyses undertaken to examine the predictors of LOS and charges revealed some interesting results. Patients aged ⩾60 years had shorter LOS than those in lower age categories. Furthermore, males had longer LOS than females. Younger age and male gender have been found to be risk factors for more severe SCIs,20 which may explain the longer LOS in these two demographic categories as observed in our study. Hospitalizations that took place in urban hospitals had longer LOS and total charges as compared with those that occurred in rural hospitals. The greater availability of highly skilled neurosurgeons, spine surgeons or orthopedic spine surgeons and sophisticated medical equipment in urban hospitals is likely to contribute to these hospitals seeing more severe cases, some of which may have been transferred from rural hospitals. The interplay of injury severity and utilization of resources could be the underlying drivers for longer LOS and higher charges in urban hospitals. Although there are no direct indicators of injury severity listed in HCUP-NIS data, variables such as discharge disposition and number of diagnoses on record provide useful proxy. The LOS and charges were found to be higher for hospitalizations with discharge disposition listed as ‘other’, which include transfer to other health-care facility, as compared with hospitalizations with a routine discharge. Patients who are transferred to other health-care facility are typically those with greater medical needs and are likely to reflect greater severity of SCI. Another proxy measure of patient severity, that is, the number of diagnoses on record, was also positively associated with LOS and total charges.

Age, gender, insurance type and number of diagnoses on the record were found to be significant predictors of discharge disposition of death among patients with SCI. Although LOS was lower among patients aged ⩾60 years, they had higher odds of discharge disposition of death than those in lower age categories. Females had ∼35% lower odds of dying during their hospitalization stay associated with SCI as compared with males. These results are consistent with those of previous studies.21, 22, 23 For example, Varma et al.21 found increasing age after 20 years (P<0.00001) and male gender (P=0.016) to be associated with in-hospital mortality.21 Patients with private insurance were less than half as likely to die during hospitalization as compared with those who paid out of pocket for the hospital stay. This result highlights the health outcome disparity contributed by lack of access to health insurance. As access to health insurance increases with the implementation of Affordable Care Act (2010), it is likely that outcome disparity such as the one observed in this study will alleviate.

This study has a few limitations. The HCUP-NIS is a discharge-level data, wherein a single patient could be counted twice because of the lack of unique patient identifiers in the data set. The economic inpatient burden of SCIs is presented in the form of charges, the amount charged by the hospital and not in the form of costs, the amount paid by the payer. Hence, it is possible that the numbers presented for inpatient burden may have overestimated the true results. The variables race/ethnicity and admission source were not included in the analysis on account of missing values. The severity of SCI could not be known using the HCUP-NIS. Injury severity is likely to be a key predictor for both resource utilization (LOS and charges) and mortality. Furthermore, we could not determine whether hospitalizations among patients with SCI were for the initial treatment of traumatic SCIs or follow-up hospitalizations post the initial treatment of SCIs. Information about hospitalizations in rehabilitation hospitals was not available in the HCUP-NIS data set. Physician fees incurred during hospitalizations were not included in the calculation of total hospitalization charges in the HCUP-NIS data set. Results of the current study should therefore be interpreted in light of these limitations. Future studies could combine data from SCI registries and administrative claims data to assess the impact of patient demographic and clinical characteristics on hospitalization outcomes in SCI patients.

The study provides important insights concerning the inpatient burden associated with SCIs in the United States. SCI-related hospitalizations were associated with higher LOS (∼2.5 times), higher hospitalization charges (∼4 times) and greater proportion of hospitalizations with discharge disposition of death (∼2.5 times) as compared with hospitalizations for other conditions. Different patient-, hospital- and discharge-level characteristics predicted outcomes of SCI-related hospitalizations. Given the higher proportion of deaths during hospitalizations observed among patients with SCI who paid out of pocket for hospital stay, policy makers should consider designing programmatic solutions with the aim of providing insurance coverage to this patient population.

Data Archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Dijkers MP . Quality of life of individuals with spinal cord injury: a review of conceptualization, measurement, and research findings. J Rehabil Res Dev 2005; 42: 87–110.

National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center Spinal cord injury facts and figures at a glance. Available from https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/PublicDocuments/fact_figures_docs/Facts%202012%20Feb%20Final.pdf (Accessed 22 February 2013).

Berkowitz M, O’Leary PK, Berkowitz M, Harvey C . Spinal Cord Injury: An Analysis of Medical and Social Costs. Demos Medical Publishing: New York. 1998 pp 75 108.

Buechner JS, Speare MC, Fontes J . Hospitalizations for spinal cord injuries, 1994–1998. Med Health R I 2000; 83: 92–93.

Krause JS, Saunders L . Risk of hospitalizations after spinal cord injury: relationship with biographic, injury, educational, and behavioural factors. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 692–697.

Webb SB Jr, Berzin E, Wingardner TS, Lorenzi ME . First year hospitalization costs for the spinal cord injured patient. Paraplegia 1978; 15: 311–318.

Price C, Makintubee S, Herndon W, Istre GR . Epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injury and acute hospitalization and rehabilitation charges for spinal cord injuries in Oklahoma, 1988–1990. Am J Epidemiol 1994; 139: 37–47.

Johnson RL, Brooks CA, Whiteneck GG . Cost of traumatic spinal cord injury in a population-based registry. Spinal Cord 1996; 34: 470–480.

French DD, Campbell RR, Sabharwal S, Nelson AL, Palacios PA, Gavin-Dreschnack D . Health care costs for patients with chronic spinal cord injury in the Veterans Health Administration. J Spinal Cord Med 2007; 30: 477–481.

Lugo LH, Salinas F, Garcia HI . Out-patient rehabilitation programme for spinal cord injured patients: evaluation of the results on motor FIM score. Disabil Rehabil 2007; 29: 873–881.

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Overview of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Available from http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp (Accessed 12 January 2012).

Proctor MR . Spinal cord injury. Crit Care Med 2002; 30 (Suppl 11): S489–S499.

Harvey C, Wilson SE, Greene CG, Berkowitz M, Stripling TE . New estimates of the direct costs of traumatic spinal cord injuries: results of a nationwide survey. Spinal Cord 1992; 30: 834–850.

De Vivo MJ, Stuart Krause J, Lammertse DP . Recent trends in mortality and causes of death among persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 1411–1419.

Jackson AB, Dijkers M, DeVivo MJ, Poczatek RB . A demographic profile of new traumatic spinal cord injuries: change and stability over 30 years. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 1740–1748.

Peek-Asa C, Zwerling C, Stallones L . Acute traumatic injuries in rural populations. Am J Public health 2004; 94: 1689–1693.

Hagglund KJ, Clay DL, Acuff M . Community reintegration for persons with spinal cord injury living in rural America. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 1998; 4: 28–40.

Kupersmith J . Quality of care in teaching hospitals: a literature review. Acad Med 2005; 80: 458–466.

Maynard FM Spinal cord injury: you do have choices. Available from http://www.rtcil.org/products/RTCIL%20publications/Health%20Issues/CHOICES.pdf (Accessed 2 March 2012).

Lieutaud T, Ndiaye A, Frost F, Chiron M . A 10-year population survey of spinal trauma and spinal cord injuries after road accidents in the Rhone area. J Neurotrauma 2010; 27: 1101–1107.

Varma A, Hill EG, Nicholas J, Selassie A . Predictors of early mortality after traumatic spinal cord injury. Spine 2010; 35: 778–783.

Bracken MB, Freeman DH, Hellenbrand K . Incidence of acute traumatic hospitalized spinal cord injury in the United States, 1970–77. Am J Epidemiol 1981; 113: 615–622.

Furlan JC, Bracken MB, Fehlings MG . Is age a key determinant of mortality and neurological outcome after acute traumatic spinal cord injury? Neurobiol Aging 2010; 31: 434–446.

Acknowledgements

This study was presented as a poster at the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) 17th Annual International Meeting, 2–6 June 2012, Washington, DC. The study was recognized with the ‘Best Student Poster Presentation Award’ at the meeting.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mahabaleshwarkar, R., Khanna, R. National hospitalization burden associated with spinal cord injuries in the United States. Spinal Cord 52, 139–144 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2013.144

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2013.144

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Evaluating safety of thrombolysis in chronic kidney disease patients presenting with pulmonary embolism using propensity score matching

Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis (2017)