Abstract

The purpose of this study is to amplify Ghana’s code of conduct, a provision made to control the behavior of political parties, candidates, and supporters in the electoral processes as well as their day-to-day activities. Although existing studies have documented the merits of organizational citizenship behavior such as sacrificial behaviors, little research has explored organizational citizenship behavior in the context of political parties. In this light, we argue that political parties’ external behavioral conformity depends on the parties’ internal behavior checks. We draw on the self-concept theory to elucidate how ethical party culture and party control shape party citizens’ self-concept to define their conforming behavior. Having investigated 404 members of different political parties, we have found that ethical party culture has a positive impact on party citizenship behavior. In addition, party control positively moderates this linkage. Theoretically, we reveal factors that positively influence organizational citizenship behavior and identify ethical organizational culture and control as components of individuals’ self-conception. From a practical standpoint, our study shows the need for political parties to construct ethical party culture and install party controls comprising process, output, and normative controls to nurture and guide party citizenship behavior. The findings can augment the Ghanaian government’s code of conduct by nurturing conforming behaviors via the parties’ internal behavior-shaping mechanisms that consequently promote external conduct consistent with the political parties’ code of conduct.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organizational citizenship behavior, defined as discretionary behavior that supports the effective and efficient operation of organizations, has become a prominent concept in the literature on organizations (Gahlawat and Kundu, 2020). Its pivotal role has led to an increasing number of studies in the public sector and management, including public service motivation, job satisfaction, and leadership behaviors (Hassan et al., 2019; Mostafa and Paul, 2015; Ritz et al., 2014). Nonetheless, existing research has yet to shed light on how it unfolds in the context of political parties. Therefore, the discussion on organizational citizenship behavior in the context of political parties can engender great insights for sustaining a peaceful political environment.

Organizational citizenship behavior details behaviors such as assisting coworkers with job tasks, being proactively involved in solving coworkers’ problems, detecting problems in accordance with the existing public service provisions, proposing appropriate solutions, and assisting organizations in maintaining a favorable image in the community (Shim and Faerman, 2017). In the literature, organizational citizenship behavior has been synonymously identified as “organizational spontaneity” and “extra-role behavior” (Henderson et al., 2020). Scholars have underscored that organizational citizenship behavior drives key outcomes of organizations (Ersoy et al., 2015; Henderson et al., 2020; Podsakoff et al., 2014). Among these scholars, Henderson et al. (2020) have noted that organizational citizenship behavior influences the maintenance and improvement of the psychological and social setting that supports organizational performance. Similarly, organizational citizenship behavior decreases work citizens’ withdrawal behaviors, increases unit performance and customer satisfaction, and encourages work incumbents to exceed the role expectations laid down by the organizations (Henderson et al., 2020). Central to these significant outcomes are its five categories: conscientiousness, sportsmanship, courtesy, altruism, and civic virtue.

In light of its significance, researchers have emphasized the essential role of several antecedents (Chan and Lai, 2017; Iqbal et al., 2020). Regarding the antecedents (Angeles Lopez-Cabarcos et al., 2020; Elstad et al., 2013; Ersoy et al., 2015; Chan and Lai, 2017; Iqbal et al., 2020), previous studies have identified factors such as employee attitudes, personal perceptions of fairness, personality traits, and leader behaviors that have a positive effect on organizational citizenship behavior (Harper, 2015). Similarly, antecedents such as positive affection, social support, and a supportive organizational climate also play a positive role (Angeles Lopez-Cabarcos et al., 2020). Bottomley et al. (2016) have added another layer of evidence by underscoring that public service motivation directly proliferates organizational citizenship behavior in organizations. Although these studies have examined several antecedents of organizational citizenship behavior, little is known about the relationship between ethical organizational culture and organizational citizenship behavior, especially under the context of the political parties’ behavior in the Global South.

Responding to this knowledge gap requires re-conceptualizing key concepts to suit the context of political parties. First, we reword ethical organizational culture as “ethical party culture” and define it as the ethical quality of the party environment, including the experiences, opinions, and expectations of the party, which aims to avoid unethical behavior and boosts ethicality (Kangas et al., 2018). Second, organizational control takes the form of “party control” and refers to the processes employed by a party’s leadership to direct attention and motivate party citizens to act in preferred ways to meet the party’s objectives (Verburg et al., 2018; Martin-Rios, 2018). Third, we modify organizational citizenship behavior as “party citizenship behavior”, referring to behaviors such as assisting co-citizens with their job tasks, being proactively involved in solving co-citizens’ problems and detecting problems in accordance with the existing public service provisions, proposing appropriate solutions, and assisting the parties in maintaining a favorable image in society (Shim and Faerman, 2017).

This study draws on the self-concept theory to propose that ethical party culture and control influence party citizens’ self-conception, leading to a self-sacrificial attribute revealed as party citizenship behavior. Simply put, external behavioral conformity depends on internal behavior checks of political parties. This study establishes this logic on the basis that an ethical culture spells out what is expected to help shape the self-concept of party citizens and influence their behaviors that define who they are. Prior studies have identified that ethical organizational culture aligns with workers’ well-being (Lee, 2020) and organizational commitment (Lee, 2020), and builds up organizational trust (Pucetaite et al., 2015), which may predict the ethical behaviors of employees. Based on these findings, we propose the hypothesis that ethical party culture plays a role in promoting and sustaining the behaviors of party citizens. In this context, this study seeks to address the research question: Whether and how do ethical party culture and control may influence political parties’ citizenship behavior?

Reflecting on the possibility of ethical (Kangas et al., 2018) and unethical behaviors (Sypniewska, 2020), this study further assesses the moderating effect of party control on the relationship between ethical party culture and party citizenship behavior. Specifically, we seek to investigate the role of party control in sustaining the relationship between ethical party culture and party citizenship behavior. Prior studies have established that organizational control reveals the organization’s ability to deliver on promises for both employees and stakeholders for the purpose of enhancing their trust (Weibel et al., 2016) and the organization’s credibility (Bridoux et al., 2016; Verburg et al., 2018). In other words, an organization’s use of organizational control shows its ability to efficiently control and manage its workers and hence boost the credibility of the organization. In this light, we assume that organizational control can sustain the link between ethical party culture and party citizenship behavior.

This study attempts to make two contributions. Theoretically, it contributes to the literature on organizational citizenship behavior by investigating the relationship between ethical organizational culture and organizational citizenship behavior. Specifically, this study emphasizes ethical party culture as a predictor of party citizenship behavior, which has not received much attention from academia. We show that the ethical culture promotes sacrificial and extra-role behaviors of party citizens via the parties’ orientation on ethical and unethical behaviors. In addition, this study examines the moderating effect of party control on the relationship between ethical party culture and party citizenship behavior. We highlight party control as a managerial tool that spells out the standards of behaviors, which sustains ethical culture and promotes party citizens’ conforming behaviors. This finding contributes to the literature on organizational control by endorsing its critical role in reinforcing the parties’ internal determinants of ethical/acceptable behavior (Verburg et al., 2018). Collectively, our findings contribute to the self-concept theory (Gecas, 1982; Rosenberg, 1965) by featuring the ethical organizational culture and organizational control as salient components of party citizens’ self-conception. Empirically, this study explores the effect of ethical party culture and control in nurturing good behaviors in the political setting of Ghana. Elections might be a one-phase event after specific periods, but conflicts arising from uncontrolled behaviors can ruin the peace of a nation in the long term. This study stresses that it is critical to begin by sustaining the internal culture and the control mechanisms of political parties to influence party citizenship behavior. The emphasis on grassroots or internal party factors is intended for more beneficial behavior of the political parties in Ghana during campaigns and elections, as outlined in Ghana’s code of conduct for political parties. Taken together, this study demonstrates the effectiveness of ethical party culture and control in sustaining party citizenship behavior for the desired external conduct.

Political parties’ Code of Conduct

Political parties’ Code of Conduct (CoC) refers to a collection of rules and standards of behavior that govern the competing political parties during successive democratic elections. The core purpose of the CoC is to guide behavior by ensuring that political parties abide by the results of an election and renounce the use of violence. In the public interest, political parties take oaths to uphold specific ethical standards to avoid violence before, during, and after elections. Dominantly, a critical issue in the transition scenarios is typically the failure of the competing parties to communicate with one another, as well as a lack of confidence in the system’s ability to generate a free and fair conclusion. In this regard, the CoC in which political parties agree on the fundamental ground principles, together with regular meetings during the campaign period, certainly helps to avoid potentially lethal confrontation while providing support for the democratic process. Precisely, the CoC is a regulation tool that seeks to enhance the security, quality, and legitimacy of an electoral process, bringing order between the competing parties, party affiliates, election officials, security forces, and the media (Idea, 2017).

In Africa, conflicts that obstruct the peace and progress of societies usually emerge during and after elections (Acled, 2016). Since 1992, elections in Ghana have been marred by acts of intimidation and violence, resulting in ballot boxes being stolen and wantonly damaged in some elections. To solve this issue, Ghana introduced its first CoC in 2000 to encourage political parties to defend the integrity and transparency of the election process as well as to improve collective interaction with electoral authorities in the fulfillment of their duties. Subsequently, new codes were introduced to guide the 2004, 2008, and 2012 elections. Each of the codes was designed to address flaws and integrate lessons learned from previous ones. In this vein, the CoC has become a salient tool to control the day-to-day activities of political parties, candidates, and their supporters during the electoral processes in Ghana (Gyampo, 2017). To maintain compliance with the CoC, party leaders meet on a monthly basis at the Ghana secretariat of the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) to examine and discuss their own compliance, and rebuke or chastise defaulting parties on the Ghana Political Parties Program (GPPP) platform. Similarly, the Regional Enforcement Bodies (REB) send monthly reports on code compliance to the National Enforcement Body, which names and shames code violators publicly. In cases where a party’s actions constitute a security threat, the National Enforcement Body (NEB) calls on the corresponding state agencies to administer penalties (Idea, 2017).

Although these measures should compel parties and their supporters to comply with the given code, some African countries still plunge into extreme violence, causing massive loss of lives and properties, which reveals the limited effect of the CoC. Therefore, research is required to unveil the parties’ internal factors and how they influence citizenship behavior for unflinching commitment to the code of conduct formulated for such political parties. Currently, this remains unexplored. In Ghana, although the long-standing power exchange between the New Democratic Congress (NDC) and the New Patriotic Party (NPP) in the midst of arguments and disagreements may be considered as parties’ sacrificial behavior, concerns should still be raised about the need to extend and reinforce the tolerance levels of parties (e.g., behavioral conformity) to ward off the pain that comes along with the barrel of the gun.

Political setting

Ghana’s pursuit of democratic governance began in 1992 some years after its independence on 6 March 1957 (Frimpong and Agyeman-Budu, 2018; Bob-Milliar and Paller, 2018). Ghana, a country in the south of the Sahara (Fig. 1), emerged as the first African country to gain independence and has drawn much attention concerning its democratic credentials (Frimpong and Agyeman-Budu, 2018). Ghana’s political leadership consists of political heads of local governments recognized as District Chief Executives (DCEs), equivalent to city mayors in other contexts. The administrative system of local governments is made up of the president and the ruling national party who exercise broad and centralized control over all district affairs in the country (Whitfield, 2009). This implies that they are also responsible for maintaining a peaceful political environment.

Ghana’s geographical location and boundary. Source: WorldAtlas.com.

Ghana introduced various laws to govern development policy implementation at all levels of the government, including, in particular, the local governments after it transitioned to democracy. The 28 political parties (Insider, 2021) (see Table 1, which demonstrates a list of political parties in Ghana) are essential instruments and representative institutions of modern democratic politics (Whitfield, 2009). Ghana’s political system has revolved around two major political parties, and the presidency has mainly shifted between the New Democratic Congress (NDC) and the New Patriotic Party (NPP) since it transitioned to a democratic regime (Briggs, 2021). The political transition was not free of conflicts. However, the conflicts were settled amicably, demonstrating a form of maturity between the two parties' leadership and their followers. The dominant two parties have constantly won the votes of two distinct ethnic groups in Ghana (Hoffman and Long, 2013). They are the Ewe in southern Volta (supporting the NDC) and the Asante in the Ashanti region (supporting the NPP). These ethnic groups have influenced the outcome of elections between the two dominant parties (Briggs, 2021). Such a political context should be prone to extremely contrary behaviors, but the differences between these two groups have only been revealed in electoral results and not in the form of violence that triggers war.

Driven by the primary goal of winning political power and producing the needed changes for the public good, the political parties have played an essential role in mobilizing citizens’ engagement (behavior) in the political process. Specifically, their role in articulating and integrating different interests, visions, and opinions (Whitfield, 2009) has contributed to the tranquility and success (i.e., peaceful settlement of party conflicts via the judiciary) of Ghana’s democracy (Adams and Asante, 2020). The political environment of Ghana is built on the aforementioned descriptions, as it is in other similar contexts.

Although there are arguments arising from inconsistencies such as accountability issues (Asunka, 2016; Frahm, 2018) and debates about the voters’ register in Ghana’s political field (Robert-Nicoud, 2019), electoral accounts locally and globally acknowledge Ghana as being exemplary in conducting peaceful elections (Whitfield, 2009). Ghanaians have periodically exercised their franchise every four years toward retaining a sitting government or changing it. Ghana has been considered as an example of peace for other emerging African democracies since the commencement of its Fourth Republic (Gyekye-Jandoh, 2014). Although Ghana’s democracy has experienced debates and conflicts from the immediate post-independence era (1957–1966), the Second Republican era (1969–1971), the Third Republican era (1979–1981), and the present Fourth Republican constitutional era (1993 to date) (Frimpong and Agyeman-Budu, 2018), the transfer of power after democratic elections, such as in 1996, 2000, 2004, and 2008, has been peaceful (Jockers et al., 2010). Similarly, debates and conflicts between the NDC and the NPP during the 2012 (Pryce and Oidtmann, 2014) and the 2020 (Adams and Asante, 2020) elections were addressed via court settlements, testifying to the parties’ devoted operation within the legal framework governing Ghana’s election. This calls into question the effectiveness of the codes of conduct of political parties in African countries where conflicts/violence have developed into wars (Acled, 2016). In this light, we anticipate that sacrificial behavior is crucial in avoiding prolonged conflicts and their repercussions.

The Fourth Republic has witnessed the transition of power between the New Patriotic Party (NPP) with affiliation to the “Danquah–Dombo–Busia tradition” and the National Democratic Congress (NDC) with affiliation to the “Nkrumahist tradition” (Bob-Milliar, 2012). These two traditions have youth groups that are presently recognized in the political and public spheres as political vigilante groups. Despite the fact that political vigilantism is linked to violence in sub-Saharan Africa, there is also evidence of non-violent engagements from some studies. In Ghana, these political vigilante groups ultimately aim at political mobilization activities and have technically promoted the ideals of their political parties in other contexts (Kyei and Berckmoes, 2020). Reflecting on this evidence, the political parties that these groups belong to may have directed their conduct. The status quo of Ghana’s democracy reveals tolerance, compliance with rules, patriotism, and maturity in the day-to-day activities of party citizens. Notably, the peaceful transition of power between the two dominant parties may elucidate the existence of conforming behaviors. Hence, the outcome of political parties’ behavior can be attributed to Ghana’s code of conduct for political parties (Gyampo, 2017). In this light, non-conformity within political parties could result in exceedingly contrary behaviors that could destroy the external coherence and the peace of the masses.

Theory and hypotheses

Self-concept Theory

This study draws on the self-concept theory to explain the effect of ethical party culture and control on party citizenship behavior. Self-concept is the result of an individual’s reflective process about himself/herself. It primarily represents the totality of an individual’s ideas and feelings regarding himself/herself as an object (Rosenberg, 1965). Generally, self-concept pinpoints individuals’ cognitive representations (mental schemas) of the knowledge they have about themselves (He et al., 2018). Self-concept has two core dimensions: self-conception and self-evaluation (Gecas, 1982). Self-conception refers to the content of an individual’s self-concept (i.e., identity) that provides meaning to the specific duty the individual performs to help better defining himself/herself. Self-evaluation refers to the evaluative and emotional components of one’s self-concept, such as how valuable an individual is in a social context. The idea of self-esteem is commonly used to operationalize self-evaluation (He et al., 2018).

This study focuses on self-conception and puts forward the concept of ethical party culture as a key component of party citizens’ self-conception that defines their party citizenship behavior. In this sense, we seek to demonstrate that ethical culture aids in comprehending party citizenship behavior, which is revealed as an extra role and sacrificial behavior. Concisely, an ethical party culture defines who party citizens are. Scholars have indicated that individuals’ self-concepts are impacted by different components such as the individuals’ beliefs and values (He et al., 2018). We further anticipate that party control, a reinforcement mechanism for ethical behavior, is another component that influences party citizens’ self-conception and behavioral outcomes such as their citizenship behavior. Drawing on self-concept theory, we aim to demonstrate ethical culture and control as key components that serve as the content of party citizens’ self-conception.

Ethical organizational culture and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB)

In the literature, ethical organizational culture is defined as the ethical quality of the working environment. It also encompasses the beliefs, values, and expectations regarding conforming and contrary behaviors as well as how the organization prevents unethical behavior and boosts ethicality (Kaptein, 2009). The ethical culture of an organization relates to its organizational virtues (Kangas et al., 2018). Ethical organizational culture consists of eight virtues: clarity, congruency of supervisors, congruency of senior management, feasibility, supportability, transparency, discuss-ability, and sanctionability, which enhance ethical conduct based on its strength in an organization (Kangas et al., 2018). This study employs clarity which details the degree to which an organization (e.g., political party) makes ethical expectations concrete and understandable to its employees (citizens). Furthermore, researchers have indicated that ethical organizational culture influences workers’ compliance with the organization’s ethical expectations and promotes ethical behavior (Toro-Arias et al., 2021). Cumulatively, these shreds of findings endorse the positive impact of ethical organizational culture on acceptable behaviors. Thus, it paves the way to assume its association with organizational citizenship behavior.

The concept of organizational citizenship behavior denotes an extraordinary role behavior, where citizens express compassion, sacrifice, volunteer, and perform tasks willingly without expecting rewards (Pimthong, 2016). Organizational citizenship behavior has been common in the literature on organizations and has been explored at the individual and group (organizational) levels for both theoretical and empirical reasons (Cheng-Chen (Timothy) Lin, 2010). The literature has shown that inter-group differences in organizational citizenship behavior are greater than intra-group (organizational) differences. However, the majority of previous studies have assessed organizational citizenship behavior at the individual level (Bateman and Organ, 1983; Williams and Anderson, 1991). Williams (1991)’s framework categorized organizational citizenship behavior towards individuals as OCBI and organizational citizenship behavior towards organizations as OCBO. Conceptually, we employ this joint perspective of OCB (as an aggregate) following Organ’s proposition (1988) that “the aggregate actions of members displaying organizational citizenship behavior facilitate organization-level functioning”. An aggregate concept of OCB is the overall sum of OCB performed towards fellow members. Prior studies have emphasized organizational citizenship behavior as an essential dimension of the outcomes of organizations, for example, employee performance (Henderson et al., 2020).

Based on these accounts, there are several reasons why ethical organizational culture (i.e., ethical party culture) is capable of proliferating extra-role behaviors of political parties. Ethical party culture will define and create an environment that constantly draws party citizens’ attention to the norms and values. This will create and maintain an intra-party climate free of opposing behaviors, which continuously enhances partisans’ awareness of an ethical environment that challenges and expects behaviors that comply with and exceed their parties’ expectations. Similarly, it may be described as having the tendency to promote patriotism and goodwill toward political processes to maintain the peaceful political environment of Ghana. In sum, the political parties’ internal strength in these areas will complement the national code of conduct, which will serve to boost external behavioral conformity. Thus, this study hypothesizes that:

H1: Ethical party culture positively relates to party citizenship behavior.

The moderating effect of organizational control

Organizational control specifies the standards for aligning the actions of individuals with the goals of organizations. It specifies the extent to which accomplished standards are monitored and rewarded (Verburg et al., 2018). There are formal and informal organizational controls. The officially documented rules that managers implement are the formal controls, whereas those centered on ethical culture and mostly made by peers are referred to as informal controls (Weibel et al., 2016).

The essentiality of an established ethical culture in an organization is only realized through its outcomes. If an ethical culture does not bring about the expected outcomes and the right behaviors and performance, then questions need to be raised concerning the control or enforcement systems put in place by authorities. In this light, the type of established organizational controls (Weibel et al., 2016) determines the kind of behavior citizens exhibit. In the study of Weibel et al. (2016), three types of control were stressed, namely outcome controls, process controls, and normative controls. Outcome controls focus on the aims, the achieved results, and whether or not promised incentives and penalties are given. Process controls are identified as adherence to procedures and rules relating to the way workers carry out their work, which also emphasizes the way of monitoring administered rewards and spelled-out punishment. Normative controls are concerned with value congruence among workers.

These specifications have influenced organizations in a positive manner. For example, Verburg et al. (2018) found a positive effect on employees’ trust and performance. Weibel et al. (2016) also emphasized the controls being pivotal to effective performance, equipping organizations with reliable means to address related recurring problems, and their general support of hedging against unacceptable behavior. As a result, organizational control has a linkage with behavior and performance. Although the human resource management literature has shown that control systems come with high monitoring costs and are less impactful and adaptive (Verburg et al., 2018), their positive contributions are still noticeable (Weibel et al., 2016).

The previous section hypothesizes that ethical party culture may guide party citizenship behavior, while such outcome expectations necessitate party citizens to adhere to the demands of internal control to ensure the effect of the ethical culture. In this light, unrelenting adherence will proliferate good behaviors and build a good party image in the eyes of the public. Firstly, output controls will have a positive influence by delivering promised rewards and punishing violations. Furthermore, its influence will be realized via its proclivity to create awareness regarding how citizens should handle their internal and external party affairs, as well as the essence of transparency among party members. Secondly, process controls will specify how duties must be carried out, which will enhance monitoring. Finally, normative controls will aid in achieving a good fit between party citizens’ values and those of their political parties (Verburg et al., 2018). Thus, this study hypothesizes the following relationship. Figure 2 depicts all hypothesized relationships.

H2: Party control positively moderates the relationship between ethical party culture and party citizenship behavior.

Methodology

Sample and procedure

This study adopted a cross-sectional survey design to sample data from 404 citizens of 28 political parties in Ghana (Insider, 2021). We collected the data via an online survey system. The questionnaire was administered through e-mail to these political parties. The questionnaire consisted of four sections. Section one solicited respondents’ information concerning their gender, age, and education. Section two solicited information about the ethical culture of their political parties. Section three solicited behavior-related information. The last section solicited information related to party controls.

Furthermore, along with the questionnaire were detailed directions on the targeted number of respondents for each party. The recipients of the e-mail (party secretaries) were asked to disseminate the questionnaires to their party officials to help attain the earmarked total number of 500 samples for the present study’s empirical estimation. A timely follow-up through emails and contact persons who paid visits to the parties’ head offices in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana facilitated the data collection process, albeit being erratic at its early stages. As a result, data collection took three months, from December 2020 to February 2021. Out of the expected data with 500 samples, 423 (84.6%) were obtained. However, the data cleaning process eliminated some invalid data, reducing the number to 404 respondents.

Our participants are party citizens or partisans. These partisans are registered members of political parties in Ghana. Their affiliation is revealed in their engagement in party activities. Affiliates or partisans avail themselves to handle tasks, thereby, representing their collective contribution to achieving the party goals. The political parties are organizations that coordinate their affiliates or partisans to compete in Ghana’s elections. This line of operation is similar to countries having especially multiple political organizations or parties, for instance, the democratic setting of the United States of America. Although the governance systems of these countries differ slightly, they can be categorized under a single kind of governance setting (Owusu Nsiah, 2019). Political parties, in the last few centuries, have become a major component of the politics of a vast majority of countries due to the fast development of modern party organizations around the world. As such, it is common for the partisans of a political party to hold similar ideas about politics and collectively accede to the ethics of their party.

Out of the 404 participants, 49% were female, and 39.1% of the respondents were aged 25–34, becoming the largest age group in the sample. In terms of their education, the university degree category recorded the highest percentage of 75.7%. Table 2 summarizes the respondents’ demographics.

Measures

Dependent variable

In the literature, organizational citizenship behavior has been conceptualized as either a unidimensional or multidimensional construct (Organ, 1988). Following the studies of Lepine et al. (2002), we also employed organizational citizenship behavior as a unitary construct. In this study, we reworded organizational citizenship behavior as party citizenship behavior and measured it following the twenty-four items employed by Coyle-Shapiro (2002). Although recent headway made by scholars presents other measurement scales of OCB, these items are reliable and have been adopted by some recent studies, for instance, by Angeles Lopez-Cabarcos et al. (2020). The items were reworded to fit the context of political parties. Partisans (respondents) were provided with a list of 24 questions (see Appendix) and asked to indicate the degree to which the behaviors were typical of their behavior in the affairs of their political parties. The question items used the 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) to collect the responses of the participants. The reliability of these items was testified by a Cronbach’s alpha (CA) value of 0.861, >0.7, the recommended cutoff point of significance.

Independent variable

We modified the concept of ethical organizational culture to reflect ethical party culture and assessed it with ten items (Kaptein, 2008; Toro-Arias et al., 2021). Ethical organizational culture comprises eight virtues (clarity, congruency of supervisors, congruency of senior management, feasibility, supportability, transparency, discuss-ability, and sanction-ability) that boost ethical conduct (Kangas et al., 2018). We used “clarity” which specifies the degree to which an organization makes ethical expectations concrete and understandable to its employees, as the main goal of political parties’ ethical culture is to spell out rules and regulations for ethical behavior. A full list of ten question items used to measure ethical party culture in this study is reported in the Appendix. Each of the items was rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha (CA = 0.816) was statistically significant, validating the reliability of these items.

Moderator variable

We reworded organizational control as party control and measured the concept with eleven items (Verburg et al., 2018). We leveraged the three forms of organizational control: process, output, and normative controls. For instance, process control items measured the degree of written rules concerning activities and procedures in the party. As shown in the Appendix, all items were reworded to fit the context of political parties. A 5-point Likert scale was used to rate each of the eleven items. The Cronbach’s alpha (CA = 0.705) was statistically significant and higher than 0.7.

Control variables

This study employed some control variables consisting of age, gender, and education, as prior research emphasized that they could have influences on organizational citizenship behavior (Ersoy et al., 2015).

Data analysis and results

Reliability and validity assessment

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted using the software package SPSS version 22 to predict the reliability, convergent, and discriminant validity of constructs/items. The reliability analysis estimated the degree of consistency between multiple measurements of each construct, which was reflected by Cronbach alpha (α) coefficients greater than the given value of 0.7 (Hair et al., 2017). All Cronbach alpha values for the three main variables in this study met the cutoff point (as detailed in the Appendix), demonstrating the reliability of the scales used to measure the variables.

We then estimated the convergent validity of constructs. This was to ascertain the intensity of the shared variance between the observed constructs/variables using the average variance extracted (AVE) and the composite reliability (CR) scores (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). All values obtained from this estimation were satisfactory and met the suggested cutoff points of 0.5 for AVE and 0.7 for CR, indicating that all constructs had good convergent validity.

Further estimation focused on the discriminant validity of constructs. We assessed whether the correlation values between the two constructs were less than the square root of their corresponding AVE values (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). As shown in Table 3, all square roots of AVE values were greater than the correlation values between the respective constructs. Thus, there was adequate discriminant validity. Consistent with prior studies, some items with loadings below 0.6 were deleted to arrive at these results (Paek et al., 2015; Ademilua et al., 2020).

Common method bias

To demonstrate that common method bias was not a problem due to the cross-sectional survey design adopted, this study conducted a one-factor test (Harman, 1967). The result showed a cumulative percentage of 26.879, which was within the recommended threshold of 50%. We also tested for multicollinearity issues. The maximum variance inflation factor (VIF), as shown in Table 2, was within the recommended threshold of 3.3 (Petter et al., 2007). This indicated that multicollinearity was not an issue in this study.

Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table 3 provided a summary of the descriptive statistics, means, standard deviation, and correlations of all variables. From the correlation results, ethical party culture, party control, and party citizenship behavior were positively and significantly related.

Hypothesis testing

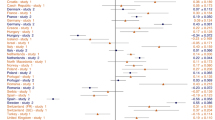

The hierarchical linear regression method was used to estimate the postulated relationship in this investigation (Cohen, 1978; Wiklund and Shepherd, 2005). As shown in Table 4, we used four regression models. In Model 1, this study tested the effect of the control variables on the dependent variable. All controls, including gender, age, and education, showed a positive association with party citizenship behavior. Model 2 tested the relationship between ethical party culture and party citizenship behavior. The coefficient generated (β = 0.662, p < 0.001) showed a significant positive relationship between ethical party culture and party citizenship behavior. Model 3 added the moderator variable, party control, into the model, and Model 4 included the interaction term between party control and ethical party culture, to estimate the moderating effect of party control on the link between ethical party culture and party citizenship behavior (see Table 4). The coefficient of the moderator variable in Model 3 (β = 0.467, p < 0.001) and the coefficient of the interaction term in Model 4 (β = 0.442, p < 0.001) provided support for Hypothesis 2.

To further assess the significance of the interaction between ethical party culture and party control, this study conducted a two-way interaction plot (Aiken and West, 1991). As Fig. 3 shows, strong party control helps sustain the positive linkage between ethical party culture and party citizenship behavior.

Discussion and conclusion

The main goal of this study is to address the research question: Whether and how do ethical party culture and control may influence political parties’ citizenship behavior? This study investigates this research question and provides several theoretical and empirical implications. Drawing on the self-concept theory, this study demonstrates that ethical party culture is a component that shapes party citizens’ self-concept. In addition to the previously validated antecedents of organizational citizenship behavior, this study adds two essential factors (ethical organizational culture and organizational control) to the emerging body of research (Angeles Lopez-Cabarcos et al., 2020; Bottomley et al., 2016; Ersoy et al., 2015; Pimthong, 2016).

This study also contributes to the literature on ethical organizational culture by assessing the effect of ethical organizational culture (coined as ethical party culture in this study) on organizational citizenship behavior (reworded as party citizenship behavior). Although prior studies have suggested ethical organizational culture as a predictor of ethical behavior (Kangas et al., 2018), few insights have been provided as for how ethical organizational culture and organizational citizenship behavior unfold in political parties. In this regard, we have found through investigation that ethical party culture has a significant positive effect on party citizenship behavior. A party’s ethical culture creates awareness of what conduct is expected of party citizens, clearly specifies behavior norms, shapes party citizens’ behavior, and challenges party citizens to exceed these standards as a measure of their loyalty to their political parties. Thus, sacrificial and extra-role behavior becomes a new standard of behavior that party citizens live up to. Overall, the finding shows a possible complementary effect of internal ethical party culture to Ghana’s code of conduct, amplifying its role in guarding the behaviors of political parties (Gyampo, 2017).

Consistent with previous research findings on the possibility of contrary organizational citizenship behavior (Sypniewska, 2020), this study has assessed the impact of party control on the relationship between ethical party culture and party citizenship behavior. The rationale behind the assessment is to decipher whether party control can hedge or amplify the effect of ethical party culture on party citizenship behavior. Our estimation has revealed that party control positively moderates the relationship between ethical party culture and party citizenship behavior. This demonstrates that party control, in the forms of output, process, and normative controls, specifies the boundaries, strengthens the impact of ethical culture on citizenship behavior, and fortifies against the possibility of unethical conduct.

Theoretical implications

The current study contributes to the self-concept theory, or specifically, the self-conception dimension (Gecas, 1982; Rosenberg, 1965) in two major ways. First, our study extends the theory by emphasizing ethical organizational culture and control as components of individuals’ self-conception. We demonstrate that these two factors positively influence citizenship behavior. Although existing research identified different components (e.g., individuals’ beliefs and values) of self-conception (He et al., 2018), little research unveiled the implications of ethical organizational culture and organizational control have for organizational citizenship behavior.

Second, the integration of party control into the link between ethical organizational culture and organizational citizenship behavior extends the self-concept theory by providing a new perceptive for the black box mechanism that strengthens the effect of ethical organizational culture on organizational citizenship behavior. Although prior research has noted that individuals’ self-conception is influenced by many components (He et al. 2018), little is known about the factors that serve as the moderation between components of self-conception and the associated behaviors.

Practical implications

Empirically, this study demonstrates the value of ethical party culture and party control in nurturing extra-role and sacrificial behavior (i.e., party citizenship behavior) in the political setting of Ghana. So far empirical research on the roles of these concepts has been limited in Ghana. Precisely, no study has investigated how these factors impact party citizenship behavior in a multiparty/democratic setting.

The empirical results of this study lead to some crucial practical implications. First, from the ethical culture perspective, political parties must sufficiently clarify how citizens should appropriately conduct themselves within the party and toward other party citizens. In this regard, the onus lies on political parties to provide adequate and clear information on the appropriate way to get proper authorization as well as how to responsibly handle the party citizens’ interests conflicting with those of the competing political parties. Taken together, political parties must strengthen their ethical culture or install new ones that can effectively shape their citizens’ behavior and avert future contrary behaviors.

Second, since contrary behaviors are likely to emerge, there is a need to intensify compliance. An effective political party control system will demonstrate significant reverence for ethical party culture while building up the trust of party citizens. In this light, the surveyed political parties should cultivate a habit of effectively monitoring the extent to which citizens achieve the objectives of their ethical culture and whether there are high extra roles or altruistic behaviors (sacrificial). The monitoring process can focus on creating a feedback mechanism where citizens promptly identify contrary behaviors and react through the controlling system for conformity. Nonetheless, citizens’ compliance and prevention of contrary behaviors call for the leadership’s attention to specifying and clarifying ambiguous rules concerning party activities, such as stating and explaining formal procedures for resolving disputes within and outside the party and the associated punishments for defaulters. Consequently, party control will impose some pressure on citizens to align behaviors with the dictates of party internal measures and Ghana’s code of conduct for political parties. Furthermore, the ability of the party leadership to regularly raise awareness of the existing or revised ethical party culture and control can be crucial to achieving the aims of enhancing party citizenship behaviors. The above implications are highly relevant and recommended for formulating party policy and shaping party practice. Along with these implications, self-sacrifice of parties will help to sustain Ghana’s political system and keep it from withering.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

Firstly, similar to the limitations in previous studies that have employed a cross-sectional survey design, this study acknowledges such limitations, which makes it possible for future research advancement. Future studies could use longitudinal data, if available in the future, and other more robust methodologies to help understand the complex interactions or causal effects between the antecedents and the dependent variable.

Secondly, our conceptualization and choice of measurement items pave the way for further investigations. We employed and assessed only one dimension (clarity) of ethical organizational culture. This deprives the literature of the possible differential effect of the other dimensions (congruency of supervisors, congruency of senior management, feasibility, supportability, transparency, discuss-ability, and sanction-ability) on organizational citizenship behavior. Therefore, future research can explore the suitability of the other dimensions in the context of political parties.

Thirdly, we conceptualized and assessed ethical party culture and control on party citizenship behavior. Although this conceptualization provides significant positive insights, not much attention has been given to the outcomes or consequences of party behavior in political settings. Thus, future research can extend the conceptual model by assessing the consequences or outcomes of party behavior, which will provide insights into whether such behavior can lead to positive outcomes in terms of party performance (efficiency and effectiveness) or otherwise.

Lastly, this study engaged the registered party citizens of the listed 28 political parties in Ghana (Table 1). However, it does not particularly target interest groups such as foot soldiers and vigilante organizations, nor does it specifically target the NDC and the NPP. Our examination covered the 28 parties because we anticipated that conflicts between either NDC or NPP and other parties might arise due to over-tolerated dominance of power, which could break the inertia of Ghana’s code of conduct. In this case, the external behavioral conformity of all parties is essential. Hence, future research can engage foot soldiers and vigilante groups to further explore the effectiveness of the studied factors as well as others that can contribute to regulating and strengthening party citizens’ internal and external conforming behavior in the interest of Ghana and similar political contexts.

Data availability

The raw cross-sectional data used to support the findings of this study would be made available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Change history

19 January 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02673-7

References

Acled (2016) The armed conflict location & event data project. https://acleddata.com/

Adams S, Asante W (2020) The judiciary and post-election conflict resolution and democratic consolidation in Ghana’s Fourth Republic. J Contemp Afr Stud 38:243–256

Ademilua VA, Lasisi TT, Ogunmokun OA, Ikhide JE (2020) Accounting for the effects of entrepreneurial orientation on SMEs’ job creation capabilities: a social capital and self‐determination perspective. J Public Aff 22(2):e2413

Aiken L, West S (1991) Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Sage, Newbury Park, CA

Angeles Lopez-Cabarcos M, Vazquez-Rodriguez P, Pineiro-Chousa J, Caby J (2020) The role of bullying in the development of organizational citizenship behaviors. J Bus Res 115:272–280

Asunka J (2016) Partisanship and political accountability in new democracies: explaining compliance with formal rules and procedures in Ghana. Res Politics 3(1):1–7

Bateman TS, Organ DW (1983) Job satisfaction and the good soldier: the relationship between affect and employee ‘citizenship’. Acad Manag J 26(4):587–595

Bob-Milliar G (2012) Political party activism in Ghana: factors influencing the decision of the politically active to join a political party. Democratization 19(4):668–689

Bob-Milliar GM, Paller JM (2018) Democratic ruptures and electoral outcomes in Africa: Ghana’s 2016 Election. Afr Spectr 53(1):5–35

Bottomley P, Mostafa AMS, Gould-Williams JS, Leon-Cazares F (2016) The impact of transformational leadership on organizational citizenship behaviours: the contingent role of public service motivation. Br J Manag 27:390–405

Bridoux F, Stofberg N, Den Hartog D (2016) Stakeholders’ responses to CSR tradeoffs: when other-orientation and trust trump material self-interest. Front Psychol 6:1–18

Briggs RC (2021) Power to which people? Explaining how electrification targets voters across party rotations in Ghana. World Dev 141:105391

Chan SHJ, Lai HYI (2017) Understanding the link between communication satisfaction, perceived justice and organizational citizenship behavior. J Bus Res 70:214–223

Cheng-Chen (Timothy) Lin AT-KTKP (2010) From organizational citizenship behaviour to team performance: the mediation of group cohesion and collective efficacy. Manag Organ Rev 6(1):55–75

Cohen J (1978) Partial products are interactions; partial powers are curve components. Psychol Bull 85:858–866

Coyle-Shapiro JaM (2002) A psychological contract perspective on organizational citizenship behavior. J Organ Behav 23:927–946

Elstad E, Christophersen K-A, Turmo A (2013) Antecedents of organizational citizenship behavior among educators in language education for adult immigrants in Norway. Adult Educ Q 63:78–96

Ersoy NC, Derous E, Born MP, Van Der Molen HT (2015) Antecedents of organizational citizenship behavior among Turkish white-collar employees in The Netherlands and Turkey. Int J Intercult Relat 49:68–79

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18:39–50

Frahm O (2018) Corruption in sub-Saharan Africa’s established and simulated democracies: the cases of Ghana, Nigeria and South Sudan. Crime Law Soc Change 70:257–274

Frimpong K, Agyeman-Budu K (2018) The rule of law and democracy in Ghana since independence: uneasy bedfellows? Afr Hum Rights Law J 18(1):244–265

Gahlawat N, Kundu SC (2020) Unravelling the relationship between high-involvement work practices and organizational citizenship behaviour: a sequential mediation approach. South Asian J Hum Resour Manag 7:165–188

Gecas V (1982) The self-concept. Annu Rev Sociol 8:1–33

Gyampo REV (2017) Political Parties Code of Conduct in Ghana. University of Ghana. Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, pp. 1–139

Gyekye-Jandoh M (2014) Elections and democracy in Africa since 2000: an update on the pertinent issues. Int J Humanit Soc Sci 4(10):11–28

Hair Jr JF, Babin BJ, Krey N (2017) Covariance-based structural equation modeling in the journal of advertising: review and recommendations. J Advert 46:163–177

Harman D (1967) A single factor test of common method variance. J Psychol 35:359–378

Harper PJ (2015) Exploring forms of organizational citizenship behaviors (OCB): antecedents and outcomes. J Manag Mark Res 18:1–16

Hassan S, Park J, Raadschelders JCN (2019) Taking a closer look at the empowerment-performance relationship: evidence from Law Enforcement Organizations. Public Adm Rev 79:427–438

He W, Zhou R-Y, Long L-R, Huang X, Hao P (2018) Self-sacrificial leadership and followers’ affiliative and challenging citizenship behaviors: a relational self-concept based study in China. Manag Organ Rev 14:105–133

Henderson AA, Foster GC, Matthews RA, Zickar MJ (2020) A psychometric assessment of OCB: clarifying the distinction between OCB and CWB and developing a revised OCB measure. J Bus Psychol 35:697–712

Hoffman B, Long J (2013) Parties, ethnicity, and voting in African elections. Comp Politics 45(2):127–146

Idea I (2017) Dialogues on voluntary codes of conduct for political parties in elections. Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, pp. 1–135

Insider G (2021) Political parties In Ghana (2021). https://ghanainsider.com/political-parties-in-ghana/#Yes_Peoples_Party_YPP

Iqbal Z, Ghazanfar F, Hameed F, Mujtaba G, Swati MA (2020) Ambidextrous leadership and change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: mediating role of psychological safety. J Public Aff 22(1):1–10

Jockers H, Kohnert D, Nugent P (2010) The successful Ghana election of 2008: a convenient myth? J Mod Afr Stud 48:95–115

Kangas M, Kaptein M, Huhtala M, Lamsa A-M, Pihlajasaari P, Feldt T (2018) Why do managers leave their organization? Investigating the role of ethical organizational culture in managerial turnover. J Bus Eth 153:707–723

Kaptein M (2008) Developing and testing a measure for the ethical culture of organizations: the corporate ethical virtues model. J Organ Behav 29:923–947

Kaptein M (2009) Ethics programs and ethical culture: a next step in unraveling their multi-faceted relationship. J Bus Eth 89:261–281

Kyei JRKO, Berckmoes LH (2020) Political Vigilante Groups in Ghana: violence or democracy? Afr Spectr 55:321–338

Lee D (2020) Impact of organizational culture and capabilities on employee commitment to ethical behavior in the healthcare sector. Serv Bus 14:47–72

Lepine JA, Erez A, Johnson DE (2002) The nature and dimensionality of organizational citizenship behavior: a critical review and meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol 87(1):52–65

Martin-Rios C (2018) Organizational control rationales in knowledge-intensive organizations: an integrative review of emerging trends. J Public Aff 18(1):e1695

Mostafa AMSG-W, Paul JSB (2015) High-performance human resource practices and employee outcomes: the mediating role of public service motivation. Public Adm Rev 75:747–757

Organ DW (1988) Organizational citizenship behavior: the good soldier syndrome. Lexington Books, Lexington, MA

Owusu Nsiah I (2019) ‘Who said we are politically inactive?’: A reappraisal of the youth and political party activism in Ghana 2004–2012 (A case of the Kumasi Metropolis). J Asian Afr Stud 54:118–135

Paek S, Schuckert M, Kim TT, Lee G (2015) Why is hospitality employees’ psychological capital important? The effects of psychological capital on work engagement and employee morale. Int J Hosp Manage 50:9–26

Petter S, Straub D, Rai A (2007) Specifying formative constructs in information systems research. Mis Q 31:623–656

Pimthong S (2016) Antecedents and consequences of organizational citizenship behavior among NGO Staff from Thailand, Myanmar, Laos and Cambodia. Int J Behav Sci 11:53–66

Podsakoff NP, Podsakoff PM, Mackenzie SB, Maynes TD, Spoelma TM (2014) Consequences of unit-level organizational citizenship behaviors: a review and recommendations for future research. J Organ Behav 35:87–119

Pryce P, Oidtmann R (2014) The 2012 general election in Ghana. Elect Stud 34:330–334

Pucetaite R, Novelskaite A, Markunaite L (2015) The mediating role of leadership relationship in building organisational trust on ethical culture of an organisation. Econ Sociol 8:11–31

Ritz A, Giauque D, Varone F, Anderfuhren-Biget S (2014) From leadership to citizenship behavior in public organizations when values matter. Rev Public Pers Adm 34:128–152

Robert-Nicoud NR (2019) Elections and borderlands in Ghana. Afr Aff 118:672–691

Rosenberg M (1965) Society and the adolescent self-image. Wesleyan University Press

Shim DC, Faerman S (2017) Government employees’ organizational citizenship behavior: the impact of public service motivation, organizational identification, and subjective OCB Norms. Int Public Manag J 20:531–559

Sypniewska B (2020) Counterproductive work behavior and organizational citizenship behavior. Adv Cogn Psychol 16:321–328

Toro-Arias J, Ruiz-Palomino P, Del Pilar Rodriguez-Cordoba M (2021) Measuring Ethical Organizational Culture: Validation of the Spanish Version of the Shortened Corporate Ethical Virtues Model. J Bus Eth 176(3):551–574

Verburg RM, Nienaber A-M, Searle RH, Weibel A, Den Hartog DN, Rupp DE (2018) The role of organizational control systems in employees’ organizational trust and performance outcomes. Group Organ Manag 43:179–206

Weibel A, Den Hartog DN, Gillespie N, Searle R, Six F, Skinner D (2016) How do controls impact employee trust in the employer? Hum Resour Manag 55:437–462

Whitfield L (2009) ‘Change for a better Ghana’: party competition, institutionalization and alternation in Ghana’s 2008 Elections. Afr Aff 108/433:621–641

Wiklund J, Shepherd D (2005) Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: a configurational approach. J Bus Ventur 20:71–91

Williams LJ, Anderson SE (1991) Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behavior. J Manag 17(3):601–617

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

It was confirmed that the research complied with ethical standards and was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations of the Academic Board of the Institute of Intellectual Property, School of Public Affairs, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China.

Informed consent

Prior to engaging the participants of this study, emails were administered to each party’s address to solicit their consent/participation. Participants engaged were those who showed interest, sent replies, and cooperated throughout the survey. The authors assured them of their anonymity and that their responses would be treated with the highest form of confidentiality. Out of the 500 sampled participants, 423 (84.6%) of them sent their answered questionnaires. The remaining 77 declined.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Horsey, E.M., Guo, L. & Huang, J. Ethical party culture, control, and citizenship behavior: Evidence from Ghana. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 238 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01698-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01698-8