Abstract

People differ in their general tendency to endorse conspiracy theories (that is, conspiracy mentality). Previous research yielded inconsistent findings on the relationship between conspiracy mentality and political orientation, showing a greater conspiracy mentality either among the political right (a linear relation) or amongst both the left and right extremes (a curvilinear relation). We revisited this relationship across two studies spanning 26 countries (combined N = 104,253) and found overall evidence for both linear and quadratic relations, albeit small and heterogeneous across countries. We also observed stronger support for conspiracy mentality among voters of opposition parties (that is, those deprived of political control). Nonetheless, the quadratic effect of political orientation remained significant when adjusting for political control deprivation. We conclude that conspiracy mentality is associated with extreme left- and especially extreme right-wing beliefs, and that this non-linear relation may be strengthened by, but is not reducible to, deprivation of political control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In the wake of major events, whether these be terrorist attacks1, global pandemics such as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak2,3 or presidential elections4, conspiracy theories predictably surge across the Internet. Conspiracy theories, defined as beliefs that a group of actors are colluding in secret to reach a malevolent goal5,6, are common across times, cultures and populations7,8. Accumulating research has revealed that a reliable predictor of belief in one conspiracy theory is belief in another conspiracy theory1,9,10,11. It therefore appears that people differ in their predisposition to explain events as conspiracies, which is sometimes referred to as ‘conspiracy mentality’ or the ‘conspiracy mindset’12,13,14. The conspiracy mindset is closely associated with belief in a wide range of existing specific conspiracy theories, as well as the endorsement of conspiracy theories created by researchers for experimental purposes15. It differs from concrete conspiracy beliefs in that it taps into the general propensity to suspect that conspiracies are at play, uncontaminated by concrete events, actors or contexts.

The political realm in particular is one key area where conspiracy beliefs are salient and thriving16. For instance, conspiracy theories are intrinsically connected to the rhetoric of populist political leaders who arguably exploit conspiracy theories for strategic reasons17,18. Importantly, citizens’ belief in conspiracy theories predicts voting behaviour and intentions19,20 and non-normative political action21,22. Traditionally, conspiracy beliefs have been associated with authoritarian worldviews23,24, as exemplified by positive relations between conspiracy beliefs and right-wing authoritarianism25,26,27. Stripping a politically right-wing stance from the surplus meaning of authoritarianism (and its strong connection to traditions and authorities), many studies have found a linear relationship between self-reported political orientation and conspiracy endorsement16,28,29, suggesting that conspiracy beliefs are more common at the political right than at the political left30,31,32,33.

However, in contrast to this simple, linear relation, numerous findings point to a curvilinear relation between political orientation and endorsement of conspiracy theories, such that people at both political extremes endorse conspiracy theories more strongly than people in the political centre do. Such a U-shaped function across the political spectrum was described for conspiracy beliefs in samples collected in the United States, the Netherlands34, Belgium35 (for conspiracy theories targeting elite groups), Sweden36, Poland37 and Germany24,38 (for conspiracy mentality). The fact that such a U-shaped function has so far been revealed in only a handful of countries that share a high degree of economic prosperity calls for further scrutiny and more thorough explanation.

One way to make sense of such a U-shaped relation between political orientation and conspiracy mentality is grounded in the content-based overlap between conspiracy beliefs and worldview explanations on the political extremes. This worldview explanation is based on the notion that extreme political movements at both the left and right share a common set of features39, which include a pronounced tendency to distrust and reject groups and ideas that differ from their own40,41,42,43,44,45,46. The left and right extremes share a worldview that centres on Manichaean demonization of ideological outgroups, which are represented not only as wrong but as immoral and dangerous47. Conspiracy theories similarly represent outgroups as evil20, and are associated with Manichaean views of history as a struggle between good and evil forces vying for control of societies20,48. Research on authoritarianism, a key antecedent of conspiracy beliefs, sometimes points to an authoritarianism symmetry hypothesis: authoritarian views in which dissent is not tolerated are observed on both the right- and left-wing extremes49,50. Likewise, both extreme positions show an affinity to a belief in simple solutions, which is also associated with conspiracy beliefs34. This worldview explanation thus suggests that the curvilinear relation in which conspiracy mentality is associated with extreme (left or right) political ideology is more or less universal across national contexts. Indeed, across time and cultures, conspiracy theories are common in the discourse of extremist fringe groups independent of ideology (extreme left, extreme right, religious fundamentalism and anti-technology)51.

There is, however, another reason to predict a U-shaped function, independent of worldview content, but as a reaction to perceived lack of political control. Political control deprivation can result from losing elections, so that one’s political values are not represented by governing parties. The experience of lack of control, in general, stimulates a desire to make sense of the social environment52,53,54. More recently, this general effect has been called into question55, but there is strong evidence that deprivation of political control, in particular, increases conspiracy theorizing16,56. When people feel locked out of power, they may be more motivated to endorse beliefs that delegitimize incumbent authorities and the outcomes of political processes57. Two recent US elections demonstrate the notion that conspiracy theories are for (political) losers58: After the election, supporters of the winning party showed weaker, and supporters of the defeated party stronger, beliefs in election-related conspiracy theories59. Supporters of extreme parties may therefore endorse conspiracy theories because they are not represented in governmental decisions (at least, in most Western countries).

This explanation, however, would suggest context dependence rather than universality. To the extent that parties from one of the extreme ends of the political continuum are in power or holding government positions, endorsement of conspiracy theories should be less pronounced among the supporters of these parties. This allows for the prediction that, in countries with a far-right government, conspiracy mentality should be particularly present on the political left (that is, a negative linear relation), whereas in countries with a far-left government, we would expect conspiracy theories particularly at the political right (a positive linear trend).

The present research sought to provide more definitive evidence regarding the nature, universality and explanations of the relationship between political orientation and conspiracy mentality, the mindset that secret sinister forces are at play. As the Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire (CMQ) mentions no concrete agents or events, it assesses this worldview without being contaminated by political bias. Study 1 investigated the relationship between political orientation and conspiracy mentality in a large and unique dataset from 23 countries (N = 33,431), allowing us not only to test the link between political orientation and conspiracy mentality in a more generalizable and fine-grained manner but also to examine whether deprivation of political control (with one’s political party excluded from government) can account for this link. A second study (N = 70,882) complemented these analyses with larger samples from 13 European countries that allowed weighting of data to match population-based distributions of age, gender, education and political leaning.

In both studies, we measured political orientation in two complementary ways. As a first approach, we measured participants’ political orientation on a single-item scale ranging from (extremely) left wing to (extremely) right wing60. Although a very brief measure, the single item is widely used in political psychology studies61,62 yielding strong evidence of validity (for example, predicting 80–90% of variance in voting behaviour63) and comparability for international research64.

While being common, economical and intuitive, there are some caveats to relying exclusively on this self-placement approach on a single item. Subjective political orientation may be susceptible to context-specific interpretations of the left–right spectrum65 because what is considered left or right can differ across countries. ‘Left wing’ in the United States might be ‘centric’ in Central Europe or ‘right of centre’ in various Northern European countries. Moreover, the left–right continuum may be interpreted differently by citizens of different countries as referring to economic or cultural issues66. These issues may lead to differences between countries that are attributable to the interpretation of the scales rather than to actual political differences.

To address this limitation, it is desirable to triangulate findings involving self-reported political orientation with a measure that is less susceptible to self-referencing and differing standards. As a second approach, we thus relied on voting intentions for political parties. These choices have no scale anchoring issues and may be more intuitively accessible to participants than their self-positioning on a Likert-type scale. Connecting voting intentions to international expert coding67 (see below) allowed us to differentiate between different aspects of the left–right continuum across different political contexts.

Results

For both studies, we dropped one item (albeit different ones, see Supplementary Sect. 2 and Supplementary Tables 3 and 4) from the Conspiracy Mentality scale to improve measurement invariance and achieve both configural and metric invariance for the four-item scale, which was computed by averaging the four remaining items (α = 0.82 in study 1, ranging from 0.62 in Macedonia to 0.89 in Poland; α = 0.83 in study 2). Parallel analyses with the five-item measure (α = 0.84) are available for both studies in Supplementary Sect. 7 but do not yield any different results. This scale should tap into respondents’ general propensity to accept conspiracy theories. To test this, we had inquired about the agreements with context-specific conspiracy theories in study 1. Across countries (random-effect meta-analytic models with strong heterogeneity; I2 values >0.96), conspiracy mentality correlated positively with left-leaning (r = 0.37, P < 0.001, 95% CI 0.28–0.45), neutral (r = 0.42, P < 0.001, 95% CI 0.33–0.51) and right-leaning conspiracy theories (r = 0.29, P < 0.001, 95% CI 0.23–0.35) (see Supplementary Figs. 1–3 for forest plots). As the arguably more adequate approach, we aggregated agreement with the diverse conspiracy theories in each country to tap into the general propensity to endorse specific conspiracy beliefs. This aggregate correlated substantially with our generic conspiracy measure that excludes any reference to concrete events or actors (r = 0.49, P < 0.001, 95% CI 0.41–0.56). Correcting for attenuation due to imperfect reliability of both measures yielded a corrected average of r = 0.73 (P < 0.001, 95% CI 0.63–0.82; Supplementary Table 5).

Analyses based on self-reported political orientation

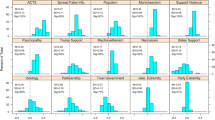

To address the question of whether conspiracy mentality is particularly pronounced on one side of the political spectrum, we tested linear and quadratic effects of self-reported political orientation on CMQ scores, respectively. Specifically, we predicted conspiracy mentality from (country-centred) political orientation, squared centred political orientation and random slopes for both. In study 1, endorsement of the CMQ items was more pronounced on the political right than the political left, as exhibited by a positive linear effect (B = 0.115, s.e. 0.037, P = 0.005, 95% CI 0.042–0.187). Study 2 did not replicate this linear relation (B = 0.068, s.e. 0.072, P = 0.362). The 95% confidence interval (−0.073 to 0.210) included both zero and the estimate obtained in study 1 (0.115). A closer look at the estimates within country suggested large heterogeneity in the linear relation (Fig. 1). While there was a clear positive relation suggestive of greater conspiracy mentality at the political right in countries spanning the centre–north of Europe such as Austria, Belgium (particularly Flanders), France, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland and Sweden, the conspiracy mentality was more pronounced on the left in countries spanning the centre–south of Europe such as Hungary, Romania and Spain.

The predicted positive quadratic relation, in contrast, was significant in study 1 (B = 0.062, s.e. 0.017, P = 0.001, 95% CI 0.029–0.095) as well as study 2 (B = 0.220, s.e. 0.031, P < 0.001, 95% CI 0.160–0.281). Unlike the linear relation, this pattern of greater conspiracy mentality at both political extremes was less heterogeneous (Fig. 2). To test whether conspiracy mentality is greater at the political extremes than at the political centre, we used the two-lines technique to check for a U-shaped relation68. This would be indicated by two significant interrupted regression lines and a sign change (negative slope for low values, positive slope for high values). To enhance interpretability, we relied on the raw, non-centred scores of political orientation, but results remain identical for within-country centred political orientation. For study 1, our analyses suggested that there was indeed a linear decrease in conspiracy mentality among the left extreme to a value of 3.4 (the break point was determined by the Robin Hood algorithm68) (b = −0.40, P < 0.001, 95% CI −0.46 to −0.33) and a linear increase from there to the extreme right (b = 0.17, P < 0.001, 95% CI 0.10–0.24) (Fig. 3). Likewise, in study 2, there a significant decrease from the left extreme to the break point of 5 (b = −0.28, P < 0.001, 95% CI −0.30 to −0.26), followed by a linear increase (b = 0.16, P < 0.001, 95% CI 0.13–0.18) (Fig. 4).

Higher density of data points is indicated by warmer colours (blue, no data points; red, a lot of data points). The dashed curve represents an unbiased but smoothed estimation of the mean at each position of the x axis. The dashed vertical line represents the break point from negative to positive slopes as estimated by the Robin Hood algorithm.

Higher density of data points is indicated by warmer colours (blue, no data points; red, a lot of data points). The dashed curve represents an unbiased but smoothed estimation of the mean at each position of the x axis. The dashed vertical line represents the break point from negative to positive slopes as estimated by the Robin Hood algorithm.

To explore the heterogeneity in both linear and quadratic relationships across countries, we conducted exploratory analyses to examine whether the size and direction of these meaningfully related to the current national government’s position on a left–right-wing scale in general, economically and socially. Due to the small number of countries in study 2, we restricted these analyses to the study 1 sample and conducted three separate analyses for each potential moderator by adding two interaction terms with the linear and the quadratic effect of political orientation, and Bonferroni-adjusted the critical value to P = 0.008 for six tests. None of these moderating analyses yielded significant interactions of either the linear or the quadratic effect (see Supplementary Sect. 6 for detailed analyses in Supplementary Tables 8–10 and corresponding scatterplots in Supplementary Figs. 5–7). This is potentially due to the lack of statistical power given the (still) small number of countries.

The control deprivation perspective allows the speculation that the relationship between political orientation and conspiracy mentality might appear because people with more extreme political views find themselves less frequently represented in the government. We thus dummy-coded whether the preferred (study 1) or recently voted (study 2) political party was in government at the time of data collection and included this as well as demographic variables (sex, age and education) as control variables. Conspiracy mentality was higher for supporters of parties not in power, as well as for less educated people (with those who did not obtain a high-school degree scoring higher than those with a high-school degree, who in turn scored higher than people with a university degree), while sex and age showed inconsistent results (Table 1). Independent of these associations, however, the quadratic term of political orientation (and the linear one in study 1) remained incrementally valid predictors (Table 1). Thus, aggregated across countries, we found support for greater conspiracy mentality at the political extremes, independent of control deprivation or level of education.

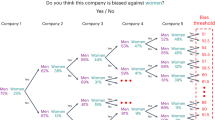

On an exploratory basis, we also tested the idea that the effect of political orientation might be attenuated once the preferred party gains power. To do so, we predicted conspiracy mentality with the linear and quadratic terms of standardized political orientation, the coding of whether the preferred party was in power at time of data collection (with random slopes per country for all three variables) and their interaction. In study 1, there was no longer a main effect of party in power (B = −0.139, s.e. 0.108, P = 0.208, 95% CI −0.350 to 0.071), but an interaction with both the linear (B = −0.184, s.e. 0.038, P < 0.001, 95% CI −0.259 to −0.109) as well as the quadratic term of political orientation (B = −0.092, s.e. 0.026, P < 0.001, 95% CI −0.142 to −0.042). These interactions indicate that people at the far right are especially prone to conspiracy mentality when their party is not in power (Fig. 5). Study 2 largely replicated this exploratory finding, also in its shape (Fig. 6). The interaction with both the linear (B = −0.164, s.e. 0.029, P < 0.001, 95% CI −0.220 to −0.107) as well as the quadratic term of political orientation (B = −0.138, s.e. 0.022, P < 0.001, 95% CI −0.180 to −0.096) indicated a significant attenuation of the relation between political orientation and conspiracy mentality for supporters of parties in power. The relation to whether the voted party was in power became substantially weaker (albeit still significant) (B = −0.497, s.e. 0.186, P = 0.017, 95% CI −0.861 to −0.132).

Analyses based on voting intentions

To address the limitations of self-placement on a political orientation scale, we also inquired about respondents’ party preferences by asking which political party they would vote or had voted for if there were an election. We used these hypothetical voting intentions (study 1) or the party that participants had voted for at the last national elections (study 2) to give participants three numerical indicators (general left–right, economic left–right and green alternative libertarian versus traditional authoritarian nationalistic (GAL–TAN)) of their political orientation corresponding to the party they indicated. For each of these (standardized) indicators, we repeated the multi-level analyses to test for linear and quadratic effects of political position on the general, economic and social left–right spectrum, while statistically controlling for sex, age, education and whether the preferred/voted party was in power (for detailed results, see Supplementary Table 17).

For the analyses based on the respective party’s stance on the general left–right dimension, both studies suggested a small quadratic relationship to conspiracy mentality as well as a descriptive but non-significant positive linear relation mirroring the results for self-reported political orientation (Table 2). Following up on the quadratic relation with a two-lines technique (that ignores the nested structure of the data and does not include control variables) suggested two significant interrupted regression lines with a sign change, indicating a U-shaped relationship for both studies. Specifically, in study 1, there was a negative linear trend on the left side of the political spectrum (b = −0.69, z = −12.72, P < 0.0001, 95% CI −0.80 to −0.59) and a positive linear trend on the right side of the political spectrum (b = 0.79, z = 23.23, P < 0.0001, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.87). Likewise, in study 2, we observed a negative slope from extreme left to the break point 0.37 (B = −0.75, z = −22.00, P < 0.0001, 95% CI −0.82 to −0.69) and a positive slope from the break point to the extreme right (B = 1.00, z = 39.68, P < 0.0001, 95% CI 0.93–1.08).

When we replaced political party preference with a quantitative indicator of the party’s stance on economic issues, no relationship between political orientation and conspiracy mentality was sufficiently strong to show when including statistical control. This was markedly different for the social left–right stance on democratic rights and freedom (GAL–TAN). Here, both studies exhibited clear positive linear relations with pronouncedly greater conspiracy mentality for supporters and voters of parties coded as traditional, authoritarian and nationalistic as opposed to green, alternative and liberal (Table 2).

Taken together, supporters of political parties that are judged as extreme on either end of the political spectrum in general terms have increased conspiracy mentality. Focusing on the position of parties on the dimension of democratic values and freedom, the link with conspiracy mentality is linear, with higher conspiracy mentality among supporters of authoritarian right-wing parties. Thus, supporters of (extreme) right-wing parties seem to have a consistently higher conspiracy mentality, whereas the same only counts for (extreme) left-wing parties of a more authoritarian make-up and with less focus on ecological and liberal values.

Discussion

Across a large sample of respondents from 26 countries and two studies, estimating self-reported political orientation and voting intentions for political parties, we found support for consistent relations between political orientation and the propensity to believe in conspiracies. Respondents at the extreme ends of the political continuum expressed more pronounced beliefs that the world is governed by secret forces operating in the dark. We had proposed two (not necessarily mutually exclusive) explanations of this pattern: (political) control deprivation and worldview consistency. In the former case, conspiracy mentality is a reaction to the fact that one’s political ideas are not part of the political mainstream, whereas in the latter, one’s general outlook on the world also determines one’s political preferences. In line with the (political) control deprivation idea, supporters of parties not included in the government harboured higher levels of conspiracy mentality in both studies. Crucially, however, controlling for whether one’s preferred party is in power still leaves the quadratic effect of political orientation intact in both studies, thus allowing the speculation that individual levels of conspiracy mentality are at least partly associated with one’s general worldview.

Which aspects of extreme political ideologies and conspiracy mentality overlap and thus create such a U-shaped relation? One prominent candidate is their Manichaean view of a black-and-white world48. Conspiracy allegations typically blame a few powerful evil people for prioritizing their own sinister goals over the welfare of all others69. Likewise, identifiable ‘evil’ groups take a prominent role in the rhetoric of both extreme right-wing parties (for example, Muslims or foreigners) as well as of extreme left-wing parties (for example, bank and hedge fund managers or the European Union). By dividing the social realm into clearly antagonistic forces of good and evil, complexity is reduced and taking a firm (and moral) position is comparatively easier. Although this seems to align well with the finding that belief in simple political solutions is a common denominator of both political extremism and belief in conspiracy theories34, the robust association even after controlling for education does not strongly support this as the relevant link.

As an important caveat, however, we have not tested the worldview hypothesis directly. Rather, we set up a critical test of whether the observed pattern may be reducible to political control deprivation (that is, not feeling represented by the parties in power). It has survived this potential falsification and therefore remains a plausible account to explain the residual connection between political orientation and conspiracy mentality. Other explanations are conceivable as well, however. Future research may further elucidate this connection and test the worldview hypothesis more directly.

Our findings add a further nuance to the observation of conspiracy mentality at both ends of the political spectrum. While conspiracy mentality peaks for supporters of parties that are either seen as extreme left wing or right wing in general, it is specifically the case for supporters of parties that are socially right wing and do not endorse liberal values. Supporters of extreme left-wing parties do not exhibit particularly strong conspiracy mentality, to the extent that these parties take a liberal stance on social issues. This is in line with the observations of a connection between conspiracy beliefs and variables tapping into non-egalitarian attitudes such as binding foundations70.

The fact that there is a strong connection between social conservatism rather than economic conservatism and conspiracy mentality also aligns well with the presumed function of conspiracy beliefs. Endorsing conspiracies results from the need to manage threat and uncertainty by creating an illusion of control52 and clear answers71. Social (rather than economic) conservatism has been connected to these same needs66,72, speaking further to the intimate connection between conspiracy mentality and social (but not economic) right-wing political orientation.

Across both studies, our findings strongly corroborate the notion that ‘conspiracy theories are for losers’58. We have interpreted this through the lens of political control deprivation (higher conspiracy mentality because one lost the vote) or as a reaction to power73. We want to caution, however, against ignoring a potential reverse causation. It is certainly feasible that the experience of losing an election increases conspiracy mentality, but as well or instead, anti-mainstream parties that a priori have very low chances of winning an election may appeal to conspiracy believers (because of their populist anti-elite rhetoric or because they can quench a need for uniqueness15). In study 1, respondents indicated which party they intended to vote for, whereas in study 2 they reported which party they had voted for at the most recent elections (thus constituting a more direct test). Comparing the beta weights of the two models (including equally scaled variables) suggests that the association was 52% larger in study 2 than in study 1 (−0.636 versus −0.418) and confidence intervals did not overlap. Although one would expect this pattern if the experience of having lost an election does indeed have an effect above the preference for non-mainstream parties, it does not offer proof. Strong tests of the causal direction can only be conducted on longitudinal data (for such data on election fraud conspiracies, see ref. 57).

In an exploratory fashion, we also examined whether diverging patterns for political orientation depended on whether one’s preferred party was in power. We found remarkably strong support for this speculation showing that, in fact, control deprivation was accompanied by an increase in conspiracy mentality almost exclusively for the (extreme) political right. This finding resonates with an ideological asymmetry observed in the US context whereby conservatives’ trust in the government is more contingent on whether the president shares their ideology than liberals’ trust in government74. Likewise, not being in power was accompanied by strong generalized anti-establishment beliefs (that is, conspiracy mentality) for the political right but not the left.

Although not the focus of the present research, our data also provided further support for greater conspiracy mentality among people with lower levels of education. According to previous analyses, low formal education is associated with belief in simple solutions as well as reduced feelings of control, which again boost belief in conspiracy theories75. Political orientation, however, had a robust association with conspiracy mentality, even after controlling for education, further ruling out that their association is due to a confound with education and resulting control deprivation.

Despite these consistent findings across a large array of diverse national contexts, we should highlight two qualifications to our findings. First, the effect sizes are overall modest. In both studies, supporting a non-governmental party and having a low education level had substantially larger associations with conspiracy mentality than either the linear or quadratic term of political orientation. Although it was not reducible to either of the two, its contribution to the prediction of conspiracy mentality was overall modest. That said, there was remarkable heterogeneity across national contexts. In particular, the linear relation ranged from strongly negative (more conspiracy mentality among self-reported leftists, as in Spain) to strongly positive (more conspiracy mentality among the political right, as in France, Poland or Sweden). Future research will have to provide an even greater diversity of national samples to explore these differences in more detail. In contrast to this diversity, the positive quadratic relation (more conspiracy mentality at the extremes) was more consistent, in particular in samples similar to the population in terms of key demographics in study 2.

As the attentive reader will notice, heterogeneity was present not only between countries but also within countries when comparing the two studies. We can only speculate about the exact reasons for this. One obvious candidate might be different compositions of the samples or slightly different recruiting strategies (for example, study 2 matches demographic population parameters but focuses on self-selected participants in panels on political research, probably with an above-average interest in politics). Another, equally speculative possibility is that these associations are more volatile than is commonly assumed. Although, in general, conspiracy mentality is a relatively stable disposition, political events and rhetoric of political elites might fuel the endorsement of such worldviews and affect the course/direction of conspiratorial beliefs of citizens.

We will illustrate the latter point with two examples. Let us consider the case of Romania. During the collection of data for study 2 (February–May 2018), the governing (leftist) government party (PSD) changed criminal procedure. The alleged aim was to fight a deep state orchestrated by George Soros, while in reality arguably to save their party leader, Liviu Dragnea, from conviction due to corruption. Throughout that period, leftists in Romania endorsed conspiracy mentality to a greater degree than right-wingers. At the (later) time of study 1 (June 2019), Dragnea had been officially convicted for over a year and the (more common) positive linear relationship was also observed in Romania. On the other hand, such a positive linear relationship was present in the Hungarian data in study 1 (July 2017), but it turned to a negative correlation in study 2 (Spring 2018). This might be another indication for the role of rhetoric by the political elites. Namely, 2017 was a pre-electoral year in Hungary, and Viktor Orban and his right-wing party intensified their attacks on the ‘Soros mafia’ and ‘Brussels‘ and gained more and more control over the Hungarian media76. At the same time, in the run-up to the elections in April 2018, conspiracy narratives became abundant on the left, with narratives such as the Hungarian Prime Minister being an agent of Vladimir Putin and leading Fidesz politicians secretly taking psychiatric care in Austria. In line with study 2, another public opinion poll from after the elections (autumn 2018) found strong conspiracy narratives on the left and, also, higher conspiracy mentality among left-wing opposition than among governmental voters77. Such post hoc explanations of unexpected differences (albeit indicative) remain speculative, but they might serve as welcome inspiration for further explorations on the role of sample characteristics and political elite rhetoric in future studies. All in all, our study provides the largest investigation to date of conspiracy mentality in terms of both number of participants and included countries, showing consistent support for stronger conspiracy mentality at both ends of the political spectrum with two different methodological approaches. Moreover, our study adds further nuance to this U-shaped function, showing that this is not symmetric, but that conspiracy mentality is particularly pronounced on the political right, particularly among voters of traditional, nationalistic and authoritarian parties. The fact that this pattern remained intact even after controlling for being in power or not also resonates with the observation that some winning parties and candidates do not just abandon their conspiracy rhetoric once they are in office (although being in power significantly curbed the asymmetrically greater conspiracy mentality on the political right wing). Instead, their anti-elite rhetoric remains intact even when they constitute a personification of exactly this elite and, our data might add, so does the anti-elite conspiracy mentality of their electorate.

Methods

To test the link between conspiracy mentality and political orientation, we aimed at collecting data from a diverse set of (predominantly European) countries. To this end, two authors (R.I. and J.-W.v.P.) issued an open call for participation via the EU COST Action network ‘Comparative Analysis of Conspiracy Theories (COMPACT)’. Specifically, we invited collaborators to contribute datasets that included all required variables from at least 300 respondents. The study was conducted in accordance with the 2016 American Psychological Association Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct78. As the project did not involve deception, vulnerable populations, identifiable data, intensive data or interventions, it was exempt from ethical approval at most participating institutions. Specifically, it was deemed to be exempt from ethics approval at Johannes Gutenberg University (Germany), Université Libre de Bruxelles (Belgium), University of Banja Luka (Bosnia and Herzegovina), University of Brasília (Brazil), University of Zagreb (Croatia), the Czech Academy of Sciences, Brno (Czech Republic), University of Rennes (France), University of Oxford (data collection in Greece), University of Iceland (Iceland), Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya (Israel), Sapienza University of Rome (Italy), the Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts (North Macedonia), University of Warsaw (Poland), Universidade Católica Portuguesa (Portugal), University of Bucharest (Romania) and University of Neuchâtel (Switzerland). The project received ethics approval by Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest (approval no. 188/2017; Hungary), the School Research Ethics Panel at Anglia Ruskin University and University of Kent Psychology Ethics (no. 201714894944604000; United Kingdom), the Ethical Board of the Institute for Political Studies, Belgrade (Serbia), the University of Bern (#2016-02-00005; Switzerland) and the Norwegian Data Protection Authority (Norway). Spanish data came from the Panel Ciudadano para la Investigación Social en Andalucía, which has an internal review of compliance with European and Spanish ethical and data protection regulations. Data collected by Kieskompas (the Netherlands and Turkey) received ethical approval under a cluster approval to J.-W.v.P. by the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (VCWE-2015-138R1; approved in October 2015 for 5 years). All participants in all countries provided explicit consent to participate before data collection and had the right to terminate participation at any time. Participants received no compensation with the exception of the United Kingdom and potentially the samples recruited via a panel company where this information is not publicly shared (Belgium, Germany, Israel, Norway, Spain and Switzerland).

This was complemented with a second study based on a large-scale two-wave online panel study conducted in 13 EU countries (we coded Belgium-Flanders and Belgium-Wallonia separately in the data, yielding 14 national categories). Data collection for study 2 was conducted by Kieskompas (‘Election compass’) in accordance with the Dutch Authority for the protection of personal information (‘Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens’) and within the ethical norms of the VU University Amsterdam (approved under the same cluster approval as for study 1). Panels were acquired through online Voting Advice Applications (VAAs) prior to elections. VAA users voluntarily agreed to join the panel and be contacted with research surveys. The potential respondents received an email invitation with an online link to participate. In countries where panel responses were insufficient (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania and Sweden), respondents were also recruited via social media, where they were invited to take the same survey as the panel respondents. The study was conducted in each participating country’s native language. For the current analyses, we relied on data from wave 1, for which data collection took place from February to May 2018.

Individual-level variables

Although individual collaborators in study 1 were free to assess additional variables or to include the questions of this study in larger surveys (to facilitate inclusion in ongoing large-scale national surveys), each contribution included the following variables (forward-translated to the local language by the respective local team; see OSF for all language versions): (a) the five-item CMQ9 (for example, ‘I think that government agencies closely monitor all citizens’, ‘I think that events which superficially seem to lack a connection are often the result of secret activities’, ‘I think that there are secret organizations that greatly influence political decisions’) on an 11-point scale ranging from certainly not (0%) to certain (100%); (b) a measure of political orientation (‘Please indicate your political orientation on a scale from left to right’) with very left-wing coded as 1 to very right-wing coded as 9; (c) a question tapping into voting intentions for political parties (‘Who would you vote for at the next national elections?’); (d) endorsement of at least three country-specific conspiracy theories (chosen to reflect a local left-wing, a local right-wing and a local conspiracy theory without clear political partisanship; complete list on OSF) on a scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). The latter were included to serve as validation of the CMQ. Finally, all surveys included demographic information on gender, age and education. As educational systems differ drastically amongst all involved countries, we recoded education in a simplified manner as low (no high-school diploma), medium (high-school diploma) and high (university degree) by means of two dummy-coded variables with high-school diploma serving as the reference category.

For study 2, as part of a larger survey, participants completed the five-item Conspiracy Mentality scale9, as well as their self-reported political orientation on a 11-point left–right scale ranging from 0 to 10 (‘In politics, people talk of ‘the left’ and the ‘the right’. How would you place your own views on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is ‘left’ and 10 is ‘right’?’). In addition, they indicated which party they voted for in the last parliamentary election, level of education, sex and age.

Samples for analysis

Each collaborator in study 1 was encouraged to contribute as large a sample as possible, preferably matching population in terms of age and gender distribution, and excluding solely student samples. No statistical methods were used to pre-determine sample sizes, but we encouraged to collected samples as large as feasible. Supplement Set. 1 lists all included samples with demographic information, descriptive statistics for the central variables and details on data collection.

The total sample contained a total of N = 37,692 participants (15,073 men, 22,469 women; 87 other; Mage = 43.32 years, s.d. 16.53 years) from 23 countries (Supplementary Table 1). Due to its large size and potential undue influence, we also conducted control analyses without the sample from the Netherlands. All relevant results remain unaltered, and these analyses can also be obtained online.

For study 2, we relied on data from the European Voter Election Studies79 (EVES). For 13 European countries (with two separate samples for the Belgian regions), we had sufficiently large samples to allow weighing by age, gender, education, region and vote in the last election to match population distribution on these variables. The data are weighted by post-stratification and Iterative proportional fitting80,81, accounting for respondents’ age, education and gender. To determine the extent of sample imbalance, we compared our observed geographic and demographic characteristics with that of the likely voter population as of 2011 (the Eurostat Census, to our knowledge, the best publicly available EU-wide data source). Moreover, we calculated additional weights for vote recall in the last parliamentary election in each country to adjust for partisan bias.

The raw sample contains a total of 70,882 participants (45,957 men, 24,925 women; Mage = 48.51 years, s.d. 16.75 years) from 13 countries (Supplementary Table 2), while the weighted sample had 47,801 participants from 13 countries (the raw number of UK respondents was too low for meaningful weighting). All analyses here are reported for the full sample. Results for the weighted sample were virtually identical and can be found in Supplementary Sect. 9 (Supplementary Tables 17–21).

Data preparation

All scale values were rescaled to bring them into a common metric (for example, transforming scales from 0 to 10 into ones from 1 to 11). To translate the voting intentions for certain political parties into a meaningful metric, we re-coded these into numerical values taken from the 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey67 (CHES) database. The CHES includes coding of a large number of European political parties, and aggregates scores obtained by surveying multiple experts per country (specializing predominantly in areas of political science). Most relevant for our current purposes were the coding for each party’s position on a left–right continuum in terms of its broad ideological stance (LRGEN), its stance on economic issues (LRECON) and its stance on democratic freedoms and rights (GAL–TAN). Thus, for each participant, we replaced the categorical variable on which they indicated the party they would vote with three numerical variables of the respective party’s stance on the left–right continuum. For parties or countries that were not included in the CHES ratings, these analyses could not be conducted and the corresponding analyses are thus based on an overall smaller sample (study 1: N = 24,324; study 2: N = 38,702). Given the sample sizes, data distribution was assumed to be normal for all variables, but this was not formally tested. All tests are reported with two-tailed P values.

Analytical strategy

As a first step, we aimed at establishing the measurement invariance and construct validity of the CMQ. Establishment of measurement invariance is a desirable procedure for cross-cultural analyses, as it ensures that there are no construct biases in the different versions of the scale. In light of the very large sample, we adopted liberal criteria recommended for such large samples82. For construct validity, we aimed to establish the validity of the CMQ by showing that it does meaningfully relate to the endorsement of country-specific conspiracy theories (that have a left-wing, right-wing or no political connotation). This was done to provide support for the notion that the CMQ is a valid indicator of a general propensity to endorse specific conspiracy beliefs.

As a second step, to estimate the (linear or curvilinear) relation between political orientation and the CMQ, we pursued a twofold strategy. One was based on respondents’ self-positioning on the political orientation scale ranging from left to right, and the other one was based on which party respondents intended to vote for (study 1) or voted for in the last election (study 2). We combined this information with reliable expert ratings of a party on the left–right continuum, as well as separate ratings for economic and social issues. Whenever we found support for a curvilinear relation, we followed up with the two-lines technique to establish support for an actual U shape68.

We report the unstandardized coefficient for the (within-country) z-standardized predictors. These weights can thus be easily interpreted as the increase or decrease on the Conspiracy Mentality scale corresponding to an increase of one s.d. on the political orientation scale (for example, B = −0.50 suggests that an increase of one standard deviation on the political orientation scale corresponds to a decrease of half a scale point on the Conspiracy Mentality scale).

In both approaches, we controlled for demographics (sex, age and education) and whether the political party the respondent intended to vote for was in power at the time of data collection (a proxy for political control deprivation). We then tested whether controlling for this proxy would attenuate or eliminate potential quadratic effects of political orientation (speaking strongly to the notion that the curvilinear relation is due to political control deprivation) or not (suggesting residual variance compatible with the notion of worldview compatibility). Explanatorily, we also tested whether the effect of political orientation was moderated by political control deprivation (that is, whether one’s party was in power at the time of data collection).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data for study 1 and 2 are available at https://osf.io/jqnd6/.

Code availability

Custom code that supports the findings of this study is available as R markdown at https://osf.io/jqnd6/.

References

Swami, V. et al. Conspiracist ideation in Britain and Austria: evidence of a monological belief system and associations between individual psychological differences and real‐world and fictitious conspiracy theories. Br. J. Psychol. 102, 443–463 (2011).

Douglas, K. M. COVID-19 conspiracy theories. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 24, 270–275 (2021).

Imhoff, R. & Lamberty, P. A bioweapon or a hoax? The link between distinct conspiracy beliefs about the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak and pandemic behavior. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 11, 1110–1118 (2020).

Golec de Zavala, A. & Federico, C. M. Collective narcissism and the growth of conspiracy thinking over the course of the 2016 United States presidential election: a longitudinal analysis. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 48, 1011–1018 (2018).

Douglas, K. M. et al. Understanding conspiracy theories. Adv. Political Psychol. 40, 3–35 (2019).

van Prooijen, J. W. The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories (Routledge, 2018).

Butter, M. & Knight, P. (eds) Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories (Routledge, 2020).

Sunstein, C. R. & Vermeule, A. Conspiracy theories: causes and cures. J. Political Philos. 17, 202–227 (2009).

Bruder, M., Haffke, P., Neave, N., Nouripanah, N. & Imhoff, R. Measuring individual differences in generic beliefs in conspiracy theories across cultures: conspiracy mentality questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 4, 225 (2013).

Goertzel, T. Belief in conspiracy theories. Political Psychol. 15, 731–742 (1994).

Wood, M. J., Douglas, K. M. & Sutton, R. M. Dead and alive: beliefs in contradictory conspiracy theories. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 3, 767–773 (2012).

Imhoff, R. & Bruder, M. Speaking (un-)truth to power: conspiracy mentality as a generalized political attitude. Eur. J. Personal. 28, 25–43 (2014).

Moscovici, S. in Changing Conceptions of Conspiracy (eds Graumann, C. F. & Moscovici, S.) 151–169 (Springer, 1987).

Moscovici, S. Reflections on the popularity of ‘conspiracy mentalities’. Int. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 33, 1–12 (2020).

Imhoff, R. & Lamberty, P. Too special to be duped: need for uniqueness motivates conspiracy beliefs. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 47, 724–734 (2017).

Imhoff, R. & Lamberty, P. How paranoid are conspiracy believers? Towards a more fine-grained understanding of the connect and disconnect between paranoia and belief in conspiracy theories. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 48, 909–926 (2018).

Bergmann, E. Conspiracy and Populism (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

Müller, J. W. Was ist Populismus?: Ein Essay (Suhrkamp Verlag, 2016).

Jolley, D. & Douglas, K. M. The social consequences of conspiracism: exposure to conspiracy theories decreases intentions to engage in politics and to reduce one’s carbon footprint. Br. J. Psychol. 105, 35–56 (2014).

Swami, V., Barron, D., Weis, L. & Furnham, A. To Brexit or not to Brexit: the roles of Islamophobia, conspiracist beliefs, and integrated threat in voting intentions for the United Kingdom European Union membership referendum. Br. J. Psychol. 109, 156–179 (2018).

Imhoff, R., Dieterle, L. & Lamberty, P. Resolving the puzzle of conspiracy worldview and political activism: belief in secret plots decreases normative but increases non-normative political engagement. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 12, 71–79 (2021).

Jolley, D. & Paterson, J. L. Pylons ablaze: examining the role of 5G COVID‐19 conspiracy beliefs and support for violence. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 59, 628–640 (2020).

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J. & Sanford, R. N. The Authoritarian Personality (Harper & Brothers, 1950).

Imhoff, R. in The Psychology of Conspiracy (eds Bilewicz, M., Cichocka, A. & Soral, W.) 122–141 (Routledge, 2015).

Abalakina‐Paap, M., Stephan, W. G., Craig, T. & Gregory, W. L. Beliefs in conspiracies. Political Psychol. 20, 637–647 (1999).

Đorđević, J. M., Žeželj, I. & Đurić, Ž. Beyond general political attitudes: conspiracy mentality as a global belief system predicts endorsement of international and local conspiracy theories. J. Soc. Political Psychol. 9, 144–158 (2021).

Grzesiak-Feldman, M. & Irzycka, M. Right-wing authoritarianism and conspiracy thinking in a Polish sample. Psychol. Rep. 105, 389–393 (2009).

Dieguez, S., Wagner-Egger, P. & Gauvrit, N. Nothing happens by accident, or does it? A low prior for randomness does not explain belief in conspiracy theories. Psychol. Sci. 26, 1762–1770 (2015).

Douglas, K. M., Sutton, R. M., Callan, M. J., Dawtry, R. J. & Harvey, A. J. Someone is pulling the strings: hypersensitive agency detection and belief in conspiracy theories. Think. Reason. 22, 57–77 (2016).

Gauchat, G. Politicization of science in the public sphere: a study of public trust in the United States, 1974 to 2010. Am. Sociol. Rev. 77, 167–187 (2012).

Jost, J. T., van der Linden, S., Panagopoulos, C. & Hardin, C. Ideological asymmetries in conformity, desire for shared reality, and the spread of misinformation. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 23, 77–83 (2018).

Miller, J. M., Saunders, K. L. & Farhart, C. E. Conspiracy endorsement as motivated reasoning: the moderating roles of political knowledge and trust. Am. J. Political Sci. 60, 824–844 (2015).

van der Linden, S., Panagopoulos, C., Azevedo, F. & Jost, J. T. The paranoid style in American politics revisited: an ideological asymmetry in conspiratorial thinking. Political Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12681 (2020).

van Prooijen, J. W., Krouwel, A. P. & Pollet, T. V. Political extremism predicts belief in conspiracy theories. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 6, 570–578 (2015).

Nera, K., Wagner-Egger, P., Bertin, P., Douglas, K. & Klein, O. A power-challenging theory of society, or a conservative mindset? Upward and downward conspiracy theories as ideologically distinct beliefs. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2769 (2021).

Krouwel, A., Kutiyski, Y., Van Prooijen, J. W., Martinsson, J. & Markstedt, E. Does extreme political ideology predict conspiracy beliefs, economic evaluations and political trust? Evidence from Sweden. J. Soc. Political Psychol. 5, 435–462 (2017).

Babińska, M. & Bilewicz, M. in Uprzedzenia w Polsce 2017 [Prejudice in Poland 2017] (eds Stefaniak, A & Winiewski, M.) 307–327 (Liberi Libri, 2019).

Imhoff, R. & Decker, O. in Rechtsextremismus der Mitte (eds Decker O., Kiess J. & Brähler, E.) 130–145 (Psychosozial Verlag, 2013).

Arendt, H. The Origins of Totalitarianism Part 1: Antisemitism (Harcourt, Brace and World, 1951).

Brandt, M. J., Reyna, C., Chambers, J. R., Crawford, J. T. & Wetherell, G. The ideological-conflict hypothesis: intolerance among both liberals and conservatives. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 23, 27–34 (2014).

Cichocka, A., Bilewicz, M., Jost, J. T., Marrouch, N. & Witkowska, M. On the grammar of politics—or why conservatives prefer nouns. Political Psychol. 37, 799–815 (2016).

Koch, A., Dorrough, A., Glöckner, A. & Imhoff, R. The ABC of society: perceived similarity in agency/socioeconomic success and conservative-progressive beliefs increases intergroup cooperation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 90, 103996 (2020).

Koch, A. et al. Groups’ warmth is a personal matter: understanding consensus on stereotype dimensions reconciles adversarial models of social evaluation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 89, 103995 (2020).

Sternisko, A., Cichocka, A. & van Bavel, J. The dark side of social movements: social identity, non-conformity, and the lure of conspiracy theories. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 35, 1–6 (2020).

van Prooijen, J. W. & Krouwel, A. P. Extreme political beliefs predict dogmatic intolerance. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 8, 292–300 (2017).

van Prooijen, J. W. & Krouwel, A. P. Psychological features of extreme political ideologies. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 28, 159–163 (2019).

Rooduijn, M. & Akkerman, T. Flank attacks: populism and left–right radicalism in Western Europe. Part. Politics 23, 193–204 (2017).

Oliver, J. E. & Wood, T. J. Conspiracy theories and the paranoid style(s) of mass opinion. Am. J. Political Sci. 58, 952–966 (2014).

Conway, L. G. III, Houck, S. C., Gornick, L. J. & Repke, M. A. Finding the Loch Ness monster: left‐wing authoritarianism in the United States. Political Psychol. 39, 1049–1067 (2018).

Van Hiel, A., Duriez, B. & Kossowska, M. The presence of left‐wing authoritarianism in Western Europe and its relationship with conservative ideology. Political Psychol. 27, 769–793 (2006).

Bartlett, J. & Miller, C. The Power of Unreason: Conspiracy Theories, Extremism and Counter-terrorism (Demos, 2010).

Douglas, K. M., Sutton, R. M. & Cichocka, A. The psychology of conspiracy theories. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 26, 538–542 (2017).

Sullivan, D., Landau, M. J. & Rothschild, Z. K. An existential function of enemyship: evidence that people attribute influence to personal and political enemies to compensate for threats to control. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 98, 434–449 (2010).

van Prooijen, J. W. & Acker, M. The influence of control on belief in conspiracy theories: conceptual and applied extensions. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 29, 753–761 (2015).

Stojanov, A. & Halberstadt, J. Does lack of control lead to conspiracy beliefs? A meta‐analysis. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 50, 955–968 (2020).

Kofta, M., Soral, W. & Bilewicz, M. What breeds conspiracy antisemitism? The role of political uncontrollability and uncertainty in the belief in Jewish conspiracy. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 118, 900–918 (2020).

Edelson, J., Alduncin, A., Krewson, C., Sieja, J. A. & Uscinski, J. E. The effect of conspiratorial thinking and motivated reasoning on belief in election fraud. Political Res. Q. 70, 933–946 (2017).

Uscinski, J. E. & Parent, J. M. American Conspiracy Theories (Oxford Univ. Press, 2014).

Nyhan, B. Media scandals are political events: how contextual factors affect public controversies over alleged misconduct by US governors. Political Res. Q. 70, 223–236 (2017).

Jost, J. T., Nosek, B. A. & Gosling, S. D. Ideology: its resurgence in social, personality, and political psychology. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 3, 126–136 (2008).

Furnham, A. & Fenton-O’Creevy, M. Personality and political orientation. Personal. Individ. Diff. 129, 88–91 (2018).

Sibley, C. G., Osborne, D. & Duckitt, J. Personality and political orientation: meta-analysis and test of a threat-constraint model. J. Res. Personal. 46, 664–677 (2012).

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W. & Sulloway, F. J. Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychol. Bull. 129, 339–375 (2003).

Huber, J. D. Values and partisanship in left–right orientations: measuring ideology. Eur. J. Political Res. 17, 599–621 (1989).

Bauer, P. C., Barberá, P., Ackermann, K. & Venetz, A. Is the left–right scale a valid measure of ideology? Political Behav. 39, 553–583 (2017).

Malka, A., Soto, C. J., Inzlicht, M. & Lelkes, Y. Do needs for security and certainty predict cultural and economic conservatism? A cross-national analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 106, 1031–1051 (2014).

Bakker, R. et al. 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey. University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill www.chesdata.eu (2015).

Simonsohn, U. Two lines: a valid alternative to the invalid testing of U-shaped relationships with quadratic regressions. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 1, 538–555 (2018).

Jolley, D., Douglas, K. M. & Sutton, R. M. Blaming a few bad apples to save a threatened barrel: the system‐justifying function of conspiracy theories. Political Psychol. 39, 465–478 (2018).

Leone, L., Giacomantonio, M. & Lauriola, M. Moral foundations, worldviews, moral absolutism and belief in conspiracy theories. Int. J. Psychol. 54, 197–204 (2019).

Marchlewska, M., Cichocka, A. & Kossowska, M. Addicted to answers: need for cognitive closure and the endorsement of conspiracy beliefs. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 48, 109–117 (2018).

Cichocka, A., Marchlewska, M., Golec de Zavala, A. & Olechowski, M. “They will not control us”: in-group positivity and belief in intergroup conspiracies. Br. J. Psychol. 107, 556–576 (2016).

Imhoff, R. & Lamberty, P. in Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories (eds Butter, M. & Knight, P.) 192–205 (Routledge, 2020).

Morisi, D., Jost, J. T. & Singh, V. An asymmetrical “President-in-power” effect. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 113, 614–620 (2019).

van Prooijen, J. ‐W. Why education predicts decreased belief in conspiracy theories. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 31, 50–58 (2017).

Bognar, E. in Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018 (eds Newman, N. et al.) 84–85 (Reuters, 2018).

Összeesküvés-elméletek, álhírek, Babonák a Magyar közvelemenyben. Political Capital https://politicalcapital.hu/pc-admin/source/documents/pc-boll-konteo-20181107.pdf (2018).

Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct (2002, amended effective June 1, 2010, and January 1, 2017). American Psychological Association http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/index.aspx (2017).

Krouwel, A., Kutiyski, Y. & Thomeczek, P. EVES: European Voter Election Studies Survey Data (Kieskompas, 2019).

Rao, J. N. K., Yung, W. & Hidiroglou, M. A. Estimating equations for the analysis of survey data using poststratification information. Sankhyā: Indian J. Stat. A 364–378 (2002).

Valliant, R. Poststratification and conditional variance estimation. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 88, 89–96 (1993).

Rutkowski, L. & Svetina, D. Assessing the hypothesis of measurement invariance in the context of large-scale international surveys. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 74, 31–57 (2014).

Richter, D. & Schupp, J. The SOEP Innovation Sample (SOEP IS). Schmollers Jahrb. 135, 389–399 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work has been coordinated, presented and discussed within the framework of EU COST Action CA15101 ‘Comparative Analysis of Conspiracy Theories (COMPACT)’. German data stem from the 2014 Innovation Sample of the Socio-Economic Panel83 (SOEP). Data from the Andalusian survey conducted in Spain come from the research project ‘Conspiracy Theories and Disinformation’ directed by Estrella Gualda (University of Huelva, Spain), whose fieldwork was supported and executed by the Institute of Advanced Social Studies (IESA-CSIC) in the context of a grant received for executing the 5th Wave of the Citizen’s Panel Survey for Social Research in Andalusia (ref. EP-1707, PIE 201710E018, IESA/CSIC, https://panelpacis.net/; E.G.). The Czech part of the study was supported by grant 20-01214S (S.G.) from the Czech Science Foundation and by RVO: 68081740 (S.G.) of the Institute of Psychology, Czech Academy of Sciences. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.I. and J.-W.v.P. initiated the project with an open call. R.I., O.K., J.H.C.A., M.Bi., A.B., M.Ba., N.B., K.B., R.B., A.C., S.D., K.M.D., A.D., B.G., S.G., G.H., A.K., P.K., A.K., S.M., J.M.D., M.S.P., M.P., L.P., G.P., A.R., R.N.R., F.A.S., M.S., R.M.S., V.S., H.T., V.T., P.W.-E., I.Ž. and J.-W.v.P. contributed to the conception of study 1 and collected data in their respective country. A.K., Y.K. and T.E. provided the data for study 2. R.I. and F.Z. analysed and interpreted the data with helpful input from O.K. R.I. drafted the article. All authors provided critical revision and approved the final version of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review information

Nature Human Behaviour thanks Bruno Castanho Silva, Federico Vegetti and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information

Supplementary Sects. 1–12 and Tables S1–S25.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Imhoff, R., Zimmer, F., Klein, O. et al. Conspiracy mentality and political orientation across 26 countries. Nat Hum Behav 6, 392–403 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01258-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01258-7

This article is cited by

-

Attitudes towards AI: measurement and associations with personality

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Die Verbreitung antisemitischer Einstellungen in Deutschland: Befunde aktueller repräsentativer Befragungen zu Trends seit 2021 und den Einflüssen von Migrationshintergrund, Religionszugehörigkeit und Religiosität

Zeitschrift für Religion, Gesellschaft und Politik (2024)

-

On modeling the correlates of conspiracy thinking

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Accuracy and social motivations shape judgements of (mis)information

Nature Human Behaviour (2023)

-

Exploring COVID-19 conspiracy theories: education, religiosity, trust in scientists, and political orientation in 26 European countries

Scientific Reports (2023)