Abstract

Objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) is a valid method to evaluate medical students’ competencies. The present cross-sectional study aimed at determining how students’ coping and health-related behaviors are associated with their psychological well-being and performance on the day of the OSCE. Fourth-year medical students answered a set of standardized questionnaires assessing their coping (BCI) and health-related behaviors before the examination (sleep PSQI, physical activity GPAQ). Immediately before the OSCE, they reported their level of instant psychological well-being on multi-dimensional visual analogue scales. OSCE performance was assessed by examiners blinded to the study. Associations were explored using multivariable linear regression models. A total of 482 students were included. Instant psychological well-being was positively associated with the level of positive thinking and of physical activity. It was negatively associated with the level of avoidance and of sleep disturbance. Furthermore, performance was negatively associated with the level of avoidance. Positive thinking, good sleep quality, and higher level of physical activity were all associated with improved well-being before the OSCE. Conversely, avoidance coping behaviors seem to be detrimental to both well-being and OSCE performance. The recommendation is to pay special attention to students who engage in avoidance and to consider implementing stress management programs.

Clinical trial: The study protocol was registered on clinicaltrial.gov NCT05393206, date of registration: 11 June 2022.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medical students face numerous stressful situations, such as night shifts, proximity to death, and hyper competitive examinations1,2,3. The exposure to those stressors might lead to intense responses represented by emotional, physiological, and cognitive changes that affect short-term well-being and performance, as well as long-term health4,5. However, students differ in their level of stress vulnerability, and the intensity of their emotional response might be dependent of their conscious and/or unconscious behaviors (e.g., coping and health-related behaviors)6,7.

Coping has been defined as “cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person”6. Four main categories of coping behaviors have been described: social support, positive thinking, active resolution, and avoidance7. Engaging in such coping behaviors can modify individuals’ levels of inner resources and influence their stress responses. For example, social support and positive reinterpretation are known to be protective factors against stress and anxiety8; conversely, avoidance, which is described as maladaptive coping behaviors, increases stress levels6,9. Further findings also suggest that coping behaviors may influence performance10. For instance, it has been shown that problem-solving (which is part of the active resolution) could be associated with better academic achievement, while avoidance was associated with decreased performance in medical students11.

Like coping behaviors, health-related behaviors can also modify the levels of inner resources available to cope with a stressful situation12. Among them, sleep quality and physical activity have a considerable influence on stress responses13,14,15. In medical students, poor sleep quality and insomnia have been associated with a high stress level and poor academic performance16,17,18. A lack of physical activity has also been found to worsen stress levels19, and to be one of the most predictive factors of burn-out symptoms in medical students20.

Among the stressful factors faced by medical students, ranking examinations are known to be one of the most anxiety-provoking events21. Objective structured clinical examination (OSCE), which is based on clinical simulation, is a valid method for the evaluation of medical skills22,23. It will soon play a major role in the evaluation of French medical students as its results will weigh heavily on their national ranking, which then determines the medical specialty of their fellowship. Traditional exams typically assess students' knowledge outside the context of clinical practice, with grading occurring after the exams and without interaction between students and assessor. In contrast, the OSCE is a clinical examination where students demonstrate specific professional skills under direct evaluation. As a result, it is expected that the OSCE would induce a stress due to the direct judgments of observing assessors, in addition to the stress associated with any exam.

Due to the specific requirements of this exam, stress management is expected to be considered important, even crucial, for students' future success and is important to understand how students cope with the stress that is generated. Two recent studies explored the relationships between coping, stress, and performance in a context of medical training in simulation24,25. These studies offer interesting findings, yet they focused on small cohorts of medical students participating in high fidelity simulation sessions without academic expectations. Thus, associations between coping strategies and stress in mandatory OSCE remain to be explored.

Moreover, investigating the relationships between psychological well-being, performance, coping, and health-related behaviors in this context would enable to pave the way for recommendations and programs designed specifically for medical students. Well-being remains a complex concept without a consensual definition26,27,28, Burns states that “psychological well-being refers to inter- and intra-individual levels of positive functioning that can include one’s sense of mastery and personal growth”29. In the present study, we use the term instant psychological well-being to characterize a state of low level of stress, with a stress perceived positively, and high self-confidence.

The purpose of this exploratory study was to describe how medical students’ coping and health-related behaviors were associated with their instant psychological well-being on the day of the OSCE. The secondary aim was to describe how medical students’ coping and health-related behaviors were associated with OSCE performance. All research questions were exploratory in nature.

Methods

Study design and population

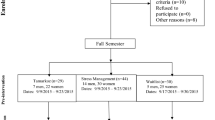

This cross-sectional, observational study involved all fourth-year medical undergraduate students who participated in mandatory OSCE scheduled at the Lyon Est school of Medicine, from the 15th to the 17th of May 2022. All students signed a written consent form before inclusion. There were no exclusion criteria.

Ethical aspects

This study is part of a larger project called ECOSTRESS. This research project was co-constructed by the health services of the Lyon 1 University, the local medical students' association, and the dean of the Lyon Est school of Medicine. All students were informed about the course of the study and its overall aim (i.e., determine factors that influence well-being and performance in order to develop appropriate tools for medical students in the future). Six investigators provided information about the study, collected signed consent forms, and enrolled students. No monetary compensation was provided. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Lyon 1 University (France, IRB 2020-05-12-01). The study protocol was registered on clinicaltrials.gov before any inclusions (clinical trial ID: NCT05393206).

Timeline

The experiment spanned 3 days. Over these 3 days, 483 students came to their exam. Before and after their exam, students who voluntarily took part in the experiment (n = 482) answered a survey split into 2 parts: some questionnaires were answered just before the exam (5 min) and others following the exam (20 min). Students came in groups of 20, therefore 20 students answered the survey simultaneously. Each student was seated at an individual desk with the computerized questionnaire on a laptop. The students were arranged to ensure that their neighbors did not see their answers.

Just before starting the OSCE, students answered several visual analogue scales (VAS) informing on their instant psychological well-being. After the OSCE, students answered a set of questionnaires to report how they behaved in terms of coping, sleep, and physical activity before their examination. Demographic information (age, gender, height, weight) was also collected.

OSCE

During OSCE, students are convened to demonstrate, with a time constraint of a few minutes, several medical competencies during consecutive realistic scenarios involving standardized patients and/or manikins. The competence evaluated through OSCE includes several clinical abilities such as practical knowledge, skills (including communication), and demonstration of professional attitudes. The national ranking exam scheduled for all sixth-year medical students in France in 2024 will incorporate an OSCE, which will contribute 30% to the total score, affecting students' national ranking and their selection of medical residencies. This local OSCE served as a summative exam, constituting 20% of the evaluation of medical students' clinical abilities during their clerkship. It was conducted under similar organizational conditions to those of following national ranking OSCE (Appendix 1).

Assessment of indicators of instant psychological well-being on the day of the OSCE

Just before their examination, students reported their instant psychological well-being on three VAS of 100 mm (Appendix 2)30,31,32. First, they reported their stress level on a scale from 0 “zero stress”, to 100 “maximum stress” (stress). Second, they reported the emotional valence of their stress, which is the way they perceived the stress, from 0 “the most negative feeling possible” (distress), to 100 a state associated with “the most positive feeling possible” (eustress) (emotional valence). Third, they reported their level of self-confidence relative to the upcoming examination, from 0 “zero self-confidence” to 100 “maximum self-confidence” (self-confidence). From these three variables, a score of instant psychological well-being was calculated as follows:

The score may range from 0 to 100; a high score indicates a high level of instant psychological well-being.

Assessment of coping behaviors

The brief cope inventory (BCI) is a 28-item questionnaire that was used to identify the coping behaviors of the students during the 2 weeks prior to the OSCE33. Answers are given using a 4-point Likert scale. Four strategies of coping behavior are extracted from the answers: active resolution (e.g., planning, active coping), positive thinking (e.g., humor, acceptance, positive reframing), social support (e.g., emotional support, venting, religion), and avoidance (e.g., denial, behavioral disengagement, substance use)7,33. Each strategy of coping behavior was scored from 1 to 4, a high score indicating the behavior was highly engaged. Each BCI scores for may range from 1 to 4.

Assessment of health-related behaviors

The Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI) is a 19-item questionnaire used to identify sleep disturbance34,35. Students were asked about their sleeping habits during the month preceding the OSCE. A high score indicates elevated sleep disturbance; a score ≥ 6/21 was considered as the sleep disturbance threshold36. The score may range from 0 to 21.

The global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ), developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), is composed of 6 main questions37. The GPAQ identifies the physical activity and sedentary behaviors (defined by the number of hours spent sitting or reclining on a typical day, not including time spent sleeping) during a regular week. The metabolic equivalent of task (MET) is the ratio of the metabolic rate of a person doing physical activity, relative to their resting metabolic rate (during quiet sitting)37. The MET is used to express the intensity of physical activity (e.g., moderate activity corresponds to 4 MET). The sum of all activities is given in MET-minutes per week. The lowest score is 0 (i.e., no activity at all) and there is no upper limit. The WHO recommendation on physical activity for health is 600 MET-minutes per week, which corresponds to 150 min of moderate intensity physical activity38. Questionnaires with missing data and/or aberrant responses were excluded from further analysis38.

Assessment of performance in the OSCE

Each OSCE was composed of 5 different scenarios and lasted 50 min. Scenarios covered a wide range of medical practices and used standardized patients or specific manikins/phantoms for procedural techniques (surgical suture, insertion of intravenous line, otoscopy) (Appendix 1). OSCE performance was assessed through standard grids by university examiners independent of the research project. The total OSCE score of each student (ranging from 0 to 40 points) was the mean of the scores of the 5 scenarios.

Statistics

Two different multivariable linear regression models were constructed. The first explored the relationships between instant psychological well-being with coping behaviors (active resolution, positive thinking, social support, avoidance) and health-related behaviors (sleep disturbance, physical activity). The second explored the relationships between academic performance (OSCE score) with coping and health-related behaviors. Both models were controlled for gender and age. As there is extensive literature linking higher BMI to lower subjective well-being39,40, the models additionally controlled for BMI. The normality of data distribution was explored using histograms and quantile–quantile plots and models’ assumptions were checked (Appendix 3). The β coefficients with their 95% confidence interval (i.e., the degree of change in the outcome variable for every 1 unit of change in the predictor variable) and the adjusted coefficients R2 (i.e., percentage of variance explained) are provided for all regression models. Additional effect sizes, along with their 95% CI, have been calculated for individuals’ predictors using the effect size package (v0.8.6). For further analysis, correlations between all coping and health-related behaviors and the three sub-components of the instant psychological well-being (stress, emotional valence, self-confidence levels) and performance were performed. For ethical reasons, participation to the protocol was offered to all the students that were scheduled to the OSCE (n = 493), no other a priori sample size was calculated. Data were analyzed using the R software (v4.1.2). All hypotheses were tested using a statistical significance level of 0.05. Quantitative data are presented by mean (standard deviation, SD) or median [interquartile range, IQR] according to the distribution of the data, and nominal data by n and percentage.

Ethics declarations

The research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by an appropriate ethics committee, that is the Institutional Review Board of the Claude Bernard University Lyon 1, Lyon, France (no. IRB 2020_05_12_01, December 2020) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Students’ characteristics

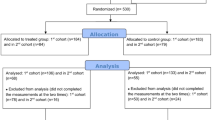

A total of 493 students were convened to the OSCE, 10 of whom did not attend the examination and 1 declined to participate; 482 were included in the present study (Fig. 1). Cronbach’s alpha values were all over 0.70 (0.86 for active resolution, 0.71 for positive thinking, 0.82 for social support, and 0.76 for avoidance), indicating a good internal consistency. The most executed coping behavior was positive thinking (M ± SD; 2.64 ± 0.64), followed by active resolution (2.07 ± 0.74), social support (1.97 ± 0.59), and avoidance (1.59 ± 0.42; Table 1). Regarding health-related behaviors, 93% of students had a sufficient level of physical activity and 53% reported sleep disturbance (Table 1). The detailed results of the PSQI and GPAQ questionnaires are presented in Appendices 4 and 5.

Flow-chart of the studied population: all 4th-year medical students convened to the academic objective structured clinical examination (OSCE). BCI brief cope inventory, PSQI Pittsburgh sleep quality index, GPAQ global physical activity questionnaire, VAS visual analogue scale (100 mm). Some PSQI (n = 5) and GPAQ (n = 29) student questionnaires were excluded from further analysis due to aberrant answers.

Instant psychological well-being (from 0 to 100)

Instant psychological well-being was positively associated with male gender (compared to female, β = 7.44, 95% CI [4.34, 10.54], p < 0.001), with the level of positive thinking (β = 6.69, 95% CI [4.52, 8.87], p < 0.001), and with the level of physical activity (β = 0.001, 95% CI [0.00, 0.00], p = 0.027) (Table 2).

Instant psychological well-being was negatively associated with age (β = − 0.78, 95% CI [− 1.51, − 0.05], p = 0.036), with the level of avoidance (β = − 9.33, 95% CI [− 12.90, − 5.78], p < 0.001), and with the level of sleep disturbance (β = − 1.08, 95% CI [− 1.52, − 0.63], p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Performance (from 0 to 40)

OSCE performance was negatively associated with the level of avoidance (β = − 1.37, 95% CI [− 2.39, − 0.35], p < 0.01; Table 3).

Stress, emotional valence, self-confidence correlations

Stress level was negatively correlated with positive thinking and physical activity, and positively correlated with social support, avoidance, and sleep disturbance (Table 4). The emotional valence level was positively correlated with positive thinking and active resolution, and negatively correlated with avoidance and sleep disturbance. The level of self-confidence was positively correlated with positive thinking, active resolution, and physical activity, and negatively correlated with social support, avoidance, and sleep disturbance (Table 4; Appendices 6 and 7).

Discussion

This exploratory study aimed to assess how coping and health-related behaviors executed by medical students prior to the OSCE were associated with their psychological well-being and performance on the examination day. The results emphasize the significance of taking both of these behaviors into account when considering well-being and performance in a real-life stressful context for undergraduate medical students.

In regards to coping behaviors, the present study found that positive thinking was positively associated with a substantial 7% increase in well-being (ranging from 4.5 to 8.9%) on the day of the OSCE. Elevated well-being just before the OSCE should help students to mobilize their inner resources. Detailed correlations revealed that positive thinking correlated with low stress level, a stress perceived more positively, and a high level of self-confidence. Similarly, active resolution correlated positively with a stress perceived more positively, and self-confidence. In a literature review focusing on medical students, Dyrbye et al. stated that positive reinterpretation (a part of positive thinking) and problem-solving (a part of active resolution) lead to adaptation, reduce anxiety, and have long-term positive influence on mental health41. Similarly, the present findings, support the value of offering preventive programs based on positive thinking and active resolution to medical students for increased instant psychological well-being in the context of a stressful exam. High level of well-being might help to foster clear thinking, focus, and memory recall. Encouraging well-being before exams may further reinforces self-care and positively impacts student’s overall well-being and life satisfaction. Positive thinking may be promoted by implementing preventive programs during medical curriculum that have already shown promising results in terms of stress reduction in students and healthcare providers42,43. Active resolution may be promoted by implementing time management training, which has by itself proven its efficacy in terms of lowering students’ stress levels44. Additional randomized controlled trials might be undertaken to assess the efficacy of preventive programs in improving psychological well-being within the context of examinations and academic achievement.

Conversely, the present results showed that engaging in avoidance was associated with a substantial − 9% decrease in well-being (ranging from − 13 to − 6%). Detailed correlations revealed that avoidance correlated with high stress level, a stress perceived more negatively, and a low level of self-confidence. Previous findings reported that behavioral disengagement, which is part of avoidance coping behaviors, causes a high stress level and is associated with depressive symptoms in the general life of college students3,45,46. While lowering avoidance behaviors seems difficult in practice, informing students about these findings (e.g., through lectures, posters, social networks) is an important step to help students identify their own maladaptive behaviors (i.e. self-distraction, self-blame, denial, substance use, and behavioral disengagement). Subsequently, offering specific guidance could help them shift from avoidance to positive thinking and active resolution.

In regards to health-related behaviors, the results of the present study showed that physical activity was associated with higher instant psychological well-being on the OSCE day. More specifically, the level of physical activity correlated with a low level of stress and a high level of self-confidence. This confirms previous studies that reported that physical activity reduces stress level and boosts self-confidence in the day-to-day life of medical students19,20,47. The present study also found that sleep disturbance was associated with a lower instant psychological well-being. More specifically, the level of sleep disturbance correlated with a higher stress level, a stress perceived more negatively, and lower self-confidence. These findings are consistent with previous findings on the relationships between sleep and stress in medical students in their daily life16,17. Sleep deprivation is associated with chronic and serious health problems such as cardiovascular diseases48,49,50, and more than half of the students herein reported sleep disturbances, suggesting that they could also be at high risk for health issues. In addition, students adopted sedentary behaviors for more than 10 h per day, which are known to be detrimental for long-term physical health51,52. Programs promoting good health hygiene have shown promising results53,54. For example, White et al. offered to public health students a self-care intervention available online focusing on nutrition, physical activity, mental health, and social support; this led to an improvement in health behaviors over the course of the semester54. Further randomized controlled trials should be conducted to evaluate the efficacy of health programs in enhancing psychological well-being notably in specific real-life stressful situations such as examination settings.

The secondary aim of the present study was to determine how OSCE performance was associated with coping and health-related behaviors. It was found that OSCE performance was negatively associated with avoidance, a result in line with studies focusing on the effects of coping styles on academic performance10,11,25. Engaging in avoidance coping behavior was, on average, associated with a substantial − 1.4 points decrease in performance, equivalent to a − 3.5% (from − 1 to − 6%) reduction in OSCE performance. Considering the substantial weight of this major assessment in students' ranking and its impact on medical specialty selection for fellowships, such variation may have profound implications in student’s professional life. As mentioned earlier, educating students about the negative impacts of avoidance on both well-being and academic performance can be an initial step in aiding them to recognize their counterproductive behaviors. There was also a significant negative correlation between sleep disturbance and OSCE performance. Previous studies found that sleep disturbance seems to be detrimental to general academic performance55,56. For instance, a trial focusing on 20 anesthesia residents in a simulated crisis scenario, found that sleep-loss was responsible for impaired non-technical skills and decreased self-confidence56; herein a negative correlation between sleep disturbance and self-confidence was found, confirming this result in a larger and younger cohort of medical students.

Finally, there was no association between physical activity and performance. Previous studies have investigated the association between physical activity and academic performance on secondary school-aged students57,58,59. Franz et al. found no association between performance and level of physical activity in secondary school students59; conversely, a study focusing on medical and health sciences students found that the probability of having a good grade was higher among the students who met the minimum level of physical activity57. We recommend conducting additional research by incorporating objective physical activity measurements, in addition to using questionnaires, as such an approach would provide a better understanding of these potential relationships within examination settings.

The present study has some limitations. Firstly, the questionnaires on physical activity, sleep quality, and coping behaviors assessed self-reported behaviors during a dissimilar temporal window (2 weeks before the examination, 1 month before the examination, or general level, respectively). This was done in order to respect the instructions of the validated questionnaires; the temporal aspect of the questionnaires could have been harmonized but this may have brought into doubt the validity of the results. Secondly, this was a single-center study, these results could benefit from an external validation in another cohort and/or another examination context. Thirdly, low-adjusted R2 were reported. While these values are similar to those reported in behavioral and psychology research, this means that the percentage of variance explained may be low. A more comprehensive understanding could thus be carried out by taking into account variables related to mental health (such as anxiety trait, or the presence of depressive symptoms) and/or revision techniques put in place by students. Fourthly, it cannot be completely ruled out that answering a questionnaire just before an exam could influence the emotional state and increase cognitive load, affecting students' abilities to perform their OSCE.

This study also has several strengths. Firstly, it is the first to investigate the relationships between psychological well-being, performance, coping, and health-related behaviors in a single protocol. Secondly, the inclusion of over 480 students enables the exploration of these relationships in a relatively large sample. Thirdly, nearly all students participated (only one refusal), ensuring a high level of internal validity and minimizing selection bias.

As a final remark, while our study did not allow us to draw conclusions on causal relationships, some interpretations might be inferred from the observed associations. From a temporal aspect, it appears more likely that coping behaviors and health-related behaviors adopted weeks before the exam influence subsequent levels of well-being and performance on the OSCE day. Nonetheless, there is still the possibility that a student who generally performs poorly academically may experience lower well-being and resort to avoidance behavior to evade upcoming situations where they anticipate failure. Future studies delineating causal and potential bi-directional influences should be addressed to identify the best way to assist medical students.

To conclude, this study reports how medical students’ coping and health-related behaviors during the weeks preceding the OSCE are associated with their psychological well-being on the day of the examination. The main findings were that the level of instant psychological well-being was positively associated with positive thinking and physical activity, while it was negatively associated with avoidance and sleep disturbance. In addition, OSCE performance was negatively associated with avoidance. These findings emphasize the importance of promoting physical activity and good sleep hygiene at universities, supporting the development of stress management programs that focus on positive thinking for medical students. They also highlight the significance of identifying and assisting students who engage in avoidance coping behaviors.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BCI:

-

Brief cope inventory

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- GPAQ:

-

Global physical activity questionnaire

- MET:

-

Metabolic equivalent of task

- OSCE:

-

Objective structured clinical examination

- PSQI:

-

Pittsburgh sleep quality index

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

- HO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Vyas, K., Stratton, T. & Soares, N. Sources of medical student stress. Educ. Health 30(3), 232. https://doi.org/10.4103/efh.EfH_54_16 (2018).

Smith, C. K., Peterson, D. F., Degenhardt, B. F. & Johnson, J. C. Depression, anxiety, and perceived hassles among entering medical students. Psychol. Health Med. 12(1), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500500429387 (2007).

Dyrbye, L. N., Thomas, M. R. & Shanafelt, T. D. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Acad. Med. 81(4), 354–373. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200604000-00009 (2006).

Shankar, N. L. & Park, C. L. Effects of stress on students’ physical and mental health and academic success. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 4(1), 5–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2016.1130532 (2016).

Romero, M. L. & Butler, L. K. Endocrinology of stress. Int. J. Comp. Psychol. 20(2), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.46867/IJCP.2007.20.02.15 (2007).

Lazarus, R. & Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping (Springer, 1984).

Baumstarck, K. et al. Assessment of coping: A new French four-factor structure of the brief COPE inventory. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 15(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-016-0581-9 (2017).

Afshar, H. et al. The association of personality traits and coping styles according to stress level. J. Res. Med. Sci. 20(4), 353–358 (2015).

Sirois, F. M. & Kitner, R. Less adaptive or more maladaptive? A meta–analytic investigation of procrastination and coping. Eur. J. Personal. 29(4), 433–444. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1985 (2015).

Edwards, J. M. & Trimble, K. Anxiety, coping and academic performance. Anxiety Stress Coping. 5(4), 337–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615809208248370 (1992).

Trucchia, S. M., Lucchese, M. S., Enders, J. E. & Fernández, A. R. Relationship between academic performance, psychological well-being, and coping strategies in medical students. Rev. Fac. Cien. Med. Univ. Nac. Cordoba 70(3), 144–152 (2013).

Abraham, C., Conner, M., Jones, F. & O’Connor, D. Health cognitions and health behaviors. In Health Psychology 2nd edn (ed. Davey, G.) 139–163 (Routledge, 2016).

Anderson, E. & Shivakumar, G. Effects of exercise and physical activity on anxiety. Front. Psychiatry 4, 27. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00027 (2013).

Ensel, W. M. & Lin, N. Physical fitness and the stress process. J. Community Psychol. 32(1), 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.10079 (2004).

Nollet, M., Wisden, W. & Franks, N. P. Sleep deprivation and stress: A reciprocal relationship. Interface Focus 10(3), 20190092. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2019.0092 (2020).

Almojali, A. I., Almalki, S. A., Alothman, A. S., Masuadi, E. M. & Alaqeel, M. K. The prevalence and association of stress with sleep quality among medical students. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 7(3), 169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jegh.2017.04.005 (2017).

Gardani, M. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of poor sleep, insomnia symptoms and stress in undergraduate students. Sleep Med. Rev. 61, 101565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101565 (2022).

Azad, M. C. et al. Sleep disturbances among medical students: A global perspective. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 11(01), 69–74. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.4370 (2015).

O’Flynn, J., Dinan, T. G. & Kelly, J. R. Examining stress: An investigation of stress, mood and exercise in medical students. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 35(1), 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2017.54 (2018).

Cecil, J., McHale, C., Hart, J. & Laidlaw, A. Behavior and burnout in medical students. Med. Educ. Online 19(1), 25209. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v19.25209 (2014).

Mennicken, A., Musselin, C., Fourcade, M., Espeland, W. & Sauder, M. Engines of anxiety: Academic rankings, reputation, and accountability. Socioecon. Rev. 16(1), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwx044 (2018).

Casey, P. M. et al. To the point: Reviews in medical education—The objective structured clinical examination. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 200(1), 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2008.09.878 (2009).

Turner, J. L. & Dankoski, M. E. Objective structured clinical exams: A critical review. Fam. Med. 40(8), 574–578 (2008).

Anton, N. E. et al. Association of medical students’ stress and coping skills with simulation performance. Simul. Healthc. J. Soc. Simul. Healthc. 16(5), 327–333. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0000000000000511 (2021).

Rusling, M. et al. Medical student coping and performance in simulated disasters. Anxiety Stress Coping 34(6), 766–777. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2021.1916481 (2021).

Galderisi, S., Heinz, A., Kastrup, M., Beezhold, J. & Sartorius, N. Toward a new definition of mental health. World Psychiatry 14(2), 231–233. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20231 (2015).

Tennant, R. et al. The Warwick–Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 5(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-63 (2007).

Dodge, R., Daly, A., Huyton, J. & Sanders, L. The challenge of defining wellbeing. Int. J. Wellbeing 2(3), 222–235. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v2i3.4 (2012).

Burns, R. Psychosocial well-being. In Encyclopedia of Geropsychology (ed. Pachana, N. A.) 1–8 (Springer, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-080-3_251-1.

Lesage, F. X. & Berjot, S. Validity of occupational stress assessment using a visual analogue scale. Occup. Med. 61(6), 434–436. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqr037 (2011).

Lesage, F. X., Berjot, S. & Deschamps, F. Clinical stress assessment using a visual analogue scale. Occup. Med. 62(8), 600–605. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqs140 (2012).

Schlatter, S. Caractérisation de La Sensibilité Au Stress et Détermination Des Moyens de Remédiation Par Stimulations Cognitives et Cérébrales. Thesis repport. University of Lyon (2021).

Muller, L. & Spitz, E. Multidimensional assessment of coping: Validation of the brief COPE among French population. Encephale 29(6), 507–518 (2003).

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R. & Kupfer, D. J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 28(2), 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 (1989).

Blais, F. C., Gendron, L., Mimeault, V. & Morin, C. M. Evaluation of insomnia: Validity of 3 questionnaires. Encephale 23(6), 447–453 (1997).

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R. & Kupfer, D. J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 28(2), 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 (1989).

Armstrong, T. & Bull, F. Development of the World Health Organization global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ). J. Public Health 14(2), 66–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-006-0024-x (2006).

World Health Organization. Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) Analysis Guide.

Wootton, R. E. et al. Evaluation of the causal effects between subjective wellbeing and cardiometabolic health: mendelian randomisation study. BMJ 362, k3788. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k3788 (2018).

Casanova, F. et al. Higher adiposity and mental health: causal inference using Mendelian randomization. Hum. Mol. Genet. 30(24), 2371–2382. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddab204 (2021).

Dyrbye, L. N., Thomas, M. R. & Shanafelt, T. D. Medical student distress: Causes, consequences, and proposed solutions. Mayo Clin. Proc. 80(12), 1613–1622. https://doi.org/10.4065/80.12.1613 (2005).

Motamed-Jahromi, M., Fereidouni, Z. & Dehghan, A. Effectiveness of positive thinking training program on nurses’ quality of work life through smartphone applications. Int. Sch. Res. Not. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/4965816 (2017).

Wang, Z. Evaluating the effect of positive ideological intervention on psychological flexibility of college students. NeuroQuantology 16(6), 295–300. https://doi.org/10.14704/nq.2018.16.6.1561 (2018).

Häfner, A., Stock, A. & Oberst, V. Decreasing students’ stress through time management training: An intervention study. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 30(1), 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-014-0229-2 (2015).

Zong, J. G. et al. Coping flexibility in college students with depressive symptoms. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 8(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-8-66 (2010).

Park, C. L. & Adler, N. E. Coping style as a predictor of health and well-being across the first year of medical school. Health Psychol. 22(6), 627–631. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.22.6.627 (2003).

Taylor, C. B., Sallis, J. F. & Needle, R. The relation of physical activity and exercise to mental health. Public Health Rep. 100(2), 195–202 (1985).

Carskadon, M. A. Sleep deprivation: Health consequences and societal impact. Med. Clin. N. Am. 88(3), 767–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2004.03.001 (2004).

Spiesshoefer, J. et al. Sleep—The yet underappreciated player in cardiovascular diseases: A clinical review from the German Cardiac Society Working Group on Sleep Disordered Breathing. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 28(2), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487319879526 (2021).

Garbarino, S., Lanteri, P., Bragazzi, N. L., Magnavita, N. & Scoditti, E. Role of sleep deprivation in immune-related disease risk and outcomes. Commun. Biol. 4(1), 1304. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-02825-4 (2021).

Hu, F. B. Sedentary lifestyle and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Lipids 38(2), 103–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11745-003-1038-4 (2003).

Park, J. H., Moon, J. H., Kim, H. J., Kong, M. H. & Oh, Y. H. Sedentary lifestyle: Overview of updated evidence of potential health risks. Korean J. Fam. Med. 41(6), 365–373. https://doi.org/10.4082/kjfm.20.0165 (2020).

Ball, S. & Bax, A. Self-care in medical education. Acad. Med. 77(9), 911–917. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200209000-00023 (2002).

White, M. A., Whittaker, S. D., Gores, A. M. & Allswede, D. Evaluation of a self-care intervention to improve student mental health administered through a distance-learning course. Am. J. Health Educ. 50(4), 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2019.1616012 (2019).

BaHammam, A. S., Alaseem, A. M., Alzakri, A. A., Almeneessier, A. S. & Sharif, M. M. The relationship between sleep and wake habits and academic performance in medical students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Educ. 12(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-12-61 (2012).

Neuschwander, A. et al. Impact of sleep deprivation on anaesthesia residents’ non-technical skills: A pilot simulation-based prospective randomized trial. Br. J. Anaesth. 119(1), 125–131. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aex155 (2017).

Chung, Q. E., Abdulrahman, S. A., Jamal Khan, M. K., Jahubar Sathik, H. B. & Rashid, A. The relationship between levels of physical activity and academic achievement among medical and health sciences students at Cyberjaya University College of Medical Sciences. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 25(5), 88–102. https://doi.org/10.21315/mjms2018.25.5.9 (2018).

Al-Drees, A. et al. Physical activity and academic achievement among the medical students: A cross-sectional study. Med. Teach. 38(sup1), 66–72. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2016.1142516 (2016).

Franz, D. D. & Feresu, S. A. The relationship between physical activity, body mass index, and academic performance and college-age students. Open J. Epidemiol. 3(1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojepi.2013.31002 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank: the health services of the Lyon Est school of medicine; Cécile Chenavas, Karima Chiter, and Céline Fiordalisi of the Lyon Est school of medicine; Denis Favre and David Romeuf of the IT department; Lucas Denoyel and Sebastien Sygiel of the simulation centre (CLESS) of the Lyon 1 University; Philip Robinson and Verena Landel of the research department of the Hospices Civils de Lyon. Many thanks to the investigators involved in the ECOSTRESS project: Ouissal Aissaou, Evane Badina, Alexandre Ben Messaoud, Marion Binay, Kenza Bretaire, Clara Chaoui, Ali Chour, Valentine Cuisinier, Matthieu Degot, Isia Delacour, Azzeddine Elmoujahid, Nour Haouchache, Marie Le Noach, Olivia Le Saux, Ludivine Lecante, Valériane Lecoq, Sacha Mairet, Sonia Maresca, Julie Marolleau, Dan Melchior, Owein Moulin, Pierre Nanette, Marie Neidecker, Benjamin Plasse, Camille Ravaux, Laura Schmidt, Alisa Tapastau, and Gaston Tran. The authors would like to warmly thank all the students who volunteered to participate.

Funding

The ECOSTRESS study was supported by resources from the Lyon Est school of medicine, Claude Bernard Lyon 1 University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.B.: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; roles/writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. T.G.: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; writing—review and editing. T.R.: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; methodology; project administration; resources; supervision; writing—review and editing. M.C.: Conceptualization; methodology; writing—review and editing. S.M.: Conceptualization; methodology; writing—review and editing. A.D.: Conceptualization; methodology; writing—review and editing. G.R.: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; project administration; resources; supervision; writing—review and editing. M.L.: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; supervision; roles/writing—original draft, writing- review and editing. S.S.: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; resources; supervision; roles/writing—original draft; writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barret, N., Guillaumée, T., Rimmelé, T. et al. Associations of coping and health-related behaviors with medical students’ well-being and performance during objective structured clinical examination. Sci Rep 14, 11298 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-61800-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-61800-1

Keywords

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.