Abstract

Recurrent involuntary autobiographical memories (IAMs) are memories retrieved unintentionally and repetitively. We examined whether the phenomenology and content of recurrent IAMs could differentiate boredom and depression, both of which are characterized by affective dysregulation and spontaneous thought. Participants (n = 2484) described their most frequent IAM and rated its phenomenological properties (e.g., valence). Structural topic modeling, a method of unsupervised machine learning, identified coherent content within the described memories. Boredom proneness was positively correlated with depressive symptoms, and both boredom proneness and depressive symptoms were correlated with more negative recurrent IAMs. Boredom proneness predicted less vivid recurrent IAMs, whereas depressive symptoms predicted more vivid, negative, and emotionally intense ones. Memory content also diverged: topics such as relationship conflicts were positively predicted by depressive symptoms, but negatively predicted by boredom proneness. Phenomenology and content in recurrent IAMs can effectively disambiguate boredom proneness from depressive symptoms in a large sample of undergraduate students from a racially diverse university.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Boredom is a common human experience characterized as a negative affective state of wanting, but failing, to engage effectively with the world1. While theoretical accounts of in-the-moment feelings of boredom suggest that it functions as a self-regulatory signal prompting exploratory action2, the individual disposition for experiencing the state more frequently and intensely3 is associated with a raft of negative outcomes4.

Perhaps the most notorious mental health challenge associated with boredom proneness is depression5. A seminal finding in boredom proneness research, the relation with depression has since been shown to be moderate to strong in many large samples5,6,7. Despite these consistent associations between the two, prior research has shown that boredom proneness and depression are distinct affective experiences8,9. That is, boredom is not simply a milder form of depression, but represents a distinct state and trait disposition. As such, the nature of the relation between boredom and depression is an important one to disentangle, to determine whether and to what extent boredom and boredom proneness represent prodromal risk factors for the development of depression and other mental health challenges.

Both boredom proneness and depression share a wide range of characteristics, including negative affect9, attentional and memory difficulties10,11, low levels of self-reported arousal12, low self-control13, and a perceived lack of meaning in life14,15. These shared characteristics extend to behaviours such as withdrawal16,17, school and occupation absence18,19, substance use20,21, and impulsiveness22,23. These similarities suggest there may be common underlying experiences between boredom proneness and depression, including anhedonia and rumination. While anhedonia is best known for its core role in depressive disorders24, it has also been linked to boredom and boredom proneness9. Similarly, rumination features in both depression25 and boredom proneness26. Analogous to depressive rumination, wherein thought is passively focused on one’s circumstances and feelings without actively changing said circumstances25, state boredom is also characterized by a failure to launch into action—a feeling that one is stuck in an unsatisfying situation, fruitlessly ruminating on the need to act while failing to implement action27. Taken together, these findings suggest that boredom and boredom proneness may represent a precursor to depression28.

Boredom features a perceived lack of, and a desire to regain, meaning14 and challenge29. Boredom is one of the more prevalent negatively valenced emotions experienced across the lifespan30 and has been associated with situations involving low perceived challenge, meaninglessness, and difficulties with attentional control8,10. What might lead boredom to function as a precursor to depression? Bargdill31 suggests that habitual boredom (an analogue to trait boredom proneness3) arises when individuals feel that they have failed to successfully realize a large life goal. According to Bargdill28, more chronic experiences of boredom spread from a focus on a singular unrealized life goal, to affecting one’s life more broadly, leading to a more passive stance towards life. This in turn may lead to a common sense of hopelessness. Indeed, Farmer and Sundberg5, in developing the original Boredom Proneness Scale, characterized boredom prone individuals as people who “experience varying degrees of depression, hopelessness, (and) loneliness” (p. 14). Similarly, Tam and colleagues32,33 propose that the frequent and intense experience of boredom may develop into clinical issues through an operant conditioning process, where a lack of meaning and control become perceived as unchanging features of one’s life. These experiences are common to both chronic boredom and depression and may include a sense of futility in engaging with the world28,34. As such, boredom may set the scene for depression to arise by engaging self-evaluations of failure and meaninglessness, coupled with a sense of hopelessness in addressing these factors.

Involuntary autobiographical memories in boredom and depression

Involuntary autobiographical memories (IAMs) may help disambiguate boredom proneness and depression. IAMs are memories of one’s personal past, retrieved unintentionally and effortlessly35. Past work shows that IAMs are sometimes experienced recurrently, such that memories of the same episode repeat involuntarily36,37,38. While these repetitions can range in frequency from several times per day to several times per year, the crux in this literature has been the subjective experience of the memory being repetitive36. Conceptual models of recurrent IAMs suggest that spontaneous cognitions of this kind act as a transdiagnostic mechanism of psychopathology39,40. In particular, recurrent IAMs and the experience of reliving vivid intrusive memories have been linked to depression41 and high levels of depressive symptoms37,38,42. The recurrence of intrusive, negatively valenced memories in depression may in part reflect one of the cardinal symptoms of the syndrome, namely rumination25: negative recurrent IAMs, and their strong impact on mood43, may initiate or maintain ruminative thought processes44. In addition, recurrent IAMs have been positively related to maladaptive coping strategies, including increased rumination and memory avoidance—both of which prolong depressive symptoms45. Thus, it is important to study IAMs in the context of mental health challenges and particular traits that may contribute to or exacerbate those challenges (e.g., boredom proneness).

While IAMs are relevant to psychopathology, they can also occur in response to nonpathological experiences. In this context, boredom proneness may be a particularly promising avenue. Participants frequently list boredom as an antecedent to IAMs46, and boredom proneness has been positively correlated with IAM frequency in daily life47. Additionally, a hallmark feature of boredom proneness is spontaneous mind wandering13. Spontaneous mind wandering itself is associated with poor self-regulation and cognitive inflexibility44, impaired memory48, and attention failures1. Importantly, mind wandering frequently involves episodic AMs49, suggesting that IAMs are a relevant experience in both depression and boredom proneness. What remains poorly understood is the actual content of spontaneous mind wandering or IAMs. Studying IAMs is thus a particularly promising way to gain insight into what goes on in the bored versus depressed mind; examining the content and nature of IAMs in the context of both boredom proneness and depression could illustrate what converges and diverges across these highly related, but distinct, experiences.

Given prior research demonstrating consistent relations between boredom proneness and depression5,8, here we thought it would be valuable to explore IAMs as a function of both. Having established that IAMs may be relevant for both depression and boredom proneness—empirically established for the former, theoretically plausible for the latter—it is possible to anticipate differences in their phenomenology and content. For example, while depression is especially characterized by negative thoughts in relation to past events [e.g., trauma50], those who are boredom prone likely experience thoughts about alternative activities and a desire for challenge, meaning, and excitement51. As such, it may well be that IAMs for the boredom prone differ from those related to depression, allowing for novel ways to identify whether one’s thought patterns are characteristic of being either boredom prone or depressed.

Phenomenology and content in involuntary autobiographical memories

As already mentioned, prior work suggests that recurrent IAMs are transdiagnostic clinical features39,40, and as such, likely involved with a range of unpleasant emotional experiences (e.g., depression symptoms and boredom proneness). Recurrent IAMs could therefore illustrate how cognitive phenomena differ depending on one’s levels of boredom proneness and depressive symptoms. In particular, recurrent IAMs are known to vary along multiple dimensions, such as phenomenology (subjective experience of the memory) and content (what one reports remembering).

First, the phenomenology of autobiographical memory has been studied for decades52. Previous studies have highlighted the reliability and factor structure of properties of autobiographical memories53, which supports the validity of our measures and constrains our current work to a robust set of phenomenological variables. Further, research has broadly examined the phenomenological properties of IAMs experienced by those with major depressive disorder [e.g., vividness, level of distress, and associated kinetic sensations54]. We, too, have shown that phenomenology (e.g., self-reported valence) of recurrent IAMs is related to mental health status in both younger37 and older adults38. Here, we focused on the properties of frequency, vividness (perceived detail, visual imagery), valence, and emotional intensity. Prior research has highlighted these properties as relevant to depression, such that negative intrusive memories are experienced vividly by those with the disorder45. Boredom may have opposing relationships with these phenomenological properties: the highly boredom prone may fail to generate vivid internal stimuli55. In this manner, IAM phenomenology could help disentangle boredom proneness and depression given distinctions in their subjective experiences.

Second, there exists a long tradition of collecting and analyzing verbal descriptions of autobiographical memories56, with recent advances enabling large-scale content analysis in tandem with phenomenological variables57. Accordingly, some researchers have examined how the content of recurrent IAMs might distinguish depression from other disorders [i.e., PTSD54,58]. Past studies suggest that recurrent IAMs in depression are commonly associated with feelings of guilt, sadness, and anxiety54, and that thematically they can be divided into five broad domains: interpersonal issues, death/illness of a significant other, illness/injury to the self, personal assault/abuse, and other58. These findings suggest that content analysis of recurrent IAMs might offer unique insights when attempting to disentangle related constructs59. We recently applied computational methods to analyze content in thousands of participants’ IAMs, without the need to manually code each one57. Specifically, we used structural topic modeling60, a method of unsupervised machine learning, to extract topics [i.e., groups of words that can be interpreted as themes61] from participants’ text descriptions of their IAMs. The critical advantage of structural topic modeling versus other related techniques [e.g., latent Dirichlet allocation61] is that researchers can then analyze how variables of interest correlate with topics. Leveraging our previous approach is fruitful here, in that large-scale content analysis allows us to examine differences in memory content as a function of boredom proneness and depression symptoms. Where content characteristic of boredom proneness may be directed outwards—“The world is not enough”—content characteristic of depression symptoms may be directed inwards in a more self-critical manner28.

For these reasons, we believe that recurrent IAMs are both theoretically relevant (e.g., involved in both depression and boredom proneness) and practically useful (e.g., enabling measurement of phenomenology and content). As such, we suggest that recurrent IAMs represent an important opportunity to disambiguate the trait disposition of boredom proneness from the syndrome of depression. We hypothesized that recurrent IAMs would be experienced differently, or have distinct experiential foci, as a function of boredom proneness and depression symptoms. That is, if the phenomenology (subjective experience), as well as content (what people report remembering) of recurrent IAMs can reliably differentiate between boredom proneness and depression symptoms, this would provide insights into the association and distinction between the two. While clearly speculative at this point, this may in turn have implications for understanding the potential for boredom and boredom proneness to function as risk factors for mental health challenges including (but not restricted to) depression.

Results

Recurrent IAM presence

Participants who experienced recurrent IAMs within the past year (n = 3345) scored significantly higher for both depression symptoms (M = 6.34, t(6065.2) = − 9.58, p < 0.001, d = − 0.25) and boredom proneness (M = 27.36, t(6040.7) = − 5.69, p < 0.001, d = − 0.15), compared to those who had not experienced recurrent IAMs within the past year or ever (n = 2805, MDASS-D = 5.08, MSBPS = 26.02).

Phenomenology

As expected, boredom proneness was significantly and positively correlated with depression symptoms (r = 0.58, p < 0.001). Further, both boredom proneness (r = − 0.16, p < 0.001) and depression symptoms (r = − 0.22, p < 0.001) were significantly correlated with recurrent IAM valence, such that higher scores on both traits were associated with more negative recurrent IAMs (Fig. 1; Table 1 shows the full correlation matrix with all variables).

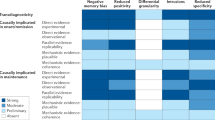

Multiple regressions were conducted for each phenomenological property of interest (i.e., frequency of recurring, detail/completeness, visual imagery, valence, emotional intensity) using depression symptoms and boredom proneness as predictors (Fig. 2). Predictors were entered simultaneously, with the phenomenological properties as outcome variables. Variance inflation factors were all less than 1.53, suggesting no issues related to multicollinearity.

Partial effects of depression symptoms vs. boredom proneness on phenomenology of recurrent IAMs. Each row reflects a different regression model predicting a phenomenological property using depression symptoms and boredom proneness scores. Abbreviations as for Fig. 1. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Depression symptoms significantly predicted more frequent recurrence of IAMs (β = 0.16, t(2481) = 6.36, p < 0.001), whereas boredom proneness did not (β = − 0.001, t(2481) = − 0.45, p = 0.656; overall adjusted R2 = 0.02). Depression symptoms significantly predicted greater subjective feelings of detail/completeness (β = 0.08, t(2479) = 3.23, p = 0.001); in contrast, boredom proneness significantly predicted lesser subjective feelings of detail/completeness (β = − 0.08, t(2479) = − 3.31, p = 0.001; overall adjusted R2 = 0.005). Depression symptoms significantly predicted stronger visual imagery (β = 0.09, t(2480) = 3.74, p < 0.001), whereas boredom proneness significantly predicted weaker visual imagery (β = − 0.07, t(2480) = − 2.91, p = 0.004; overall adjusted R2 = 0.005). Depression symptoms significantly predicted more negative valence (β = − 0.20, t(2481) = − 8.09, p < 0.001), whereas boredom proneness did not (β = − 0.004, t(2481) = − 1.80, p = 0.07; overall adjusted R2 = 0.05). Finally, depression symptoms significantly predicted more emotional intensity (β = 0.24, t(2481) = 9.80, p < 0.001), whereas boredom proneness did not (β = − 0.001, t(2481) = − 0.10, p = 0.917; overall adjusted R2 = 0.05; Fig. 2).

Using the method recommended by [62; Eq. 4], slopes were significantly different between depression symptoms and boredom proneness for all phenomenological properties (ps < 0.001). These differences remained significant after using the Benjamini–Hochberg method63 of controlling the false discovery rate (q = 0.1).

Content

Supervised dimension projection

Figure 3 illustrates the words in recurrent IAMs most strongly related to depression symptoms and boredom proneness. Qualitatively, while words involving negative valence were strongly related to high scores on both constructs, there appeared to be more internally focused content in high depression symptoms (e.g., “feel”, “cry”) versus externally focused content in high boredom proneness (e.g., “harm”, “wrong”).

Supervised dimension projection plot of words in recurrent IAMs using depression symptoms and boredom proneness. Words in blue were most related to depression symptoms, whereas words in red were most related to boredom proneness. Words in pink were most related to both depression symptoms and boredom proneness, whereas words in grey were not significantly related to either. Note that some nonwords in this figure can be attributed to either contractions (e.g., “m” from “I’m”; “ve” from “I’ve”) or phrases (e.g., “vu” from “déjà vu”).

Topic modeling

The final topic structure obtained is shown in Table 2. The goal of these researcher-assigned labels was simply to facilitate interpretation of content by topic.

Predicting topic prevalence

First, to confirm the validity of the researcher-assigned labels, we estimated topic prevalence using self-reported IAM valence as a predictor. Valence was a significant predictor for all topics (ps < 0.02); qualitatively, positive labels were given to topics predicted by positive valence and vice versa (Fig. 4).

Second, to examine whether content changed as a function of depression and boredom proneness, we estimated topic prevalence using depression symptoms and boredom proneness as predictors. Critically, depression symptoms and boredom proneness explained unique variance in several topics (Fig. 5). Depression symptoms were significantly predictive of greater use of topic 8 (“Distressing relationship conflicts”; B = 0.001, p = 0.01), and less use of topic 5 (“Nostalgic trips”; B = − 0.001, p = 0.03) and topic 6 (“Family holidays”; B = − 0.0007, p = 0.04). Boredom proneness was significantly predictive of less use of topic 14 (“Pleasant family gatherings”; B = − 0.001, p < 0.001).

Predicted topic prevalence using depression symptoms and boredom proneness. DASS-D Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales—Depression Subscale, SBPS Short Boredom Proneness Scale. For this figure, DASS-D and SBPS scores were converted to percent of maximum possible scores (POMP; Cohen et al., 1999) so that units could be compared on the same scale (i.e., 0% = lowest possible score on either measure, 100% = highest possible score). Coloured asterisks refer to significant predictors. Black asterisks refer to models where slopes significantly differed from each other. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Using methods recommended by [62; Eq. 4], regression coefficients were significantly different between depression symptoms and boredom proneness for topics 8 (“Distressing relationship conflicts”; p = 0.005) and 14 (“Pleasant family gatherings”; p = 0.006). These differences remained significant after using the Benjamini–Hochberg method63 of controlling the false discovery rate (q = 0.1). Slopes were not significantly different for any other topic (ps > 0.065).

As an exploratory analysis to control for valence, we also estimated topic prevalence with depression symptoms, boredom proneness, and valence as predictors (see Supplemental Materials). Results were similar to the previous model (depression symptoms and boredom proneness as predictors, without valence). As in the previous model, depression symptoms were significantly predictive of greater use of topic 8 (“Distressing relationship conflicts”; B = 0.001, p = 0.02), but also less use of topic 9 (“Vivid, cued, negative events”; B = − 0.001, p = 0.03) and greater use of topic 14 (“Pleasant family gatherings”; B = 0.001, p = 0.049). Inconsistent with the previous model (without valence), boredom proneness was significantly predictive of less use of topic 8 (“Distressing relationship conflicts”; B = − 0.0008, p = 0.01). As with the previous model (without valence), slopes were significantly different between depression symptoms and boredom proneness for topics 8 (“Distressing relationship conflicts”; p = 0.005) and 14 (“Pleasant family gatherings”; p = 0.006), even after applying the same Benjamini–Hochberg corrections63. Slopes were not significantly different for any other topic (ps > 0.051).

Discussion

We investigated whether the related constructs of boredom proneness and depression symptoms could be distinguished using the phenomenology and content of recurrent IAMs. Though we did not directly examine the role of demographics on the patterns we report, our sample was derived from data collected at a large Canadian university, consisting of undergraduate students from racially diverse backgrounds. Results showed that phenomenology and content in recurrent IAMs can effectively disambiguate boredom proneness from depression symptoms.

Prior research suggests that boredom and depression are distinct affective experiences8,9, yet has left largely unanswered how they differ. Documenting and differentiating relations between these two affective states is important. First, boredom and depression share a large number of problematic correlates, such as substance use20,21, poorer diet and exercise64, social withdrawal and loneliness65, problem gambling66, and even suicidal ideation67. Combatting these problematic outcomes requires a nuanced understanding of their causes.

It is of theoretical importance to understand better the differences between boredom and depression. A hallmark feature of both is that they involve an acute lack of perceived meaning in life or one’s activities14,51. The question remains as to why the lack of meaning in some contexts lead to boredom, and in others depression. Boredom and depression are well-established correlates5,6, which some have interpreted to reflect the possibility that chronic boredom may function as a potential precursor or risk factor for depression, for example when boredom is left to fester unresolved28. By understanding the differences between the two, it becomes possible to identify what marks the point at which boredom turns, over time, into depression.

With respect to phenomenology of IAMs, boredom and depression showed some distinct patterns. While both showed negative relations with valence, such that higher trait boredom or depressive symptoms were associated with more negatively valenced IAMs (Fig. 1), there were notable differences in other domains. Namely, boredom proneness was not significantly predictive of either the frequency or emotional intensity of experiencing IAMs (Fig. 2), whereas higher levels of depressive symptoms were associated with more frequent and emotionally intense IAMs. Although preliminary, this may reflect one avenue by which boredom proneness differs from depressive symptoms—a simple increase in the frequency and intensity of negatively valenced IAMs appears to be characteristic of depression rather than boredom proneness. Critically, boredom proneness and depressive symptoms had opposing relationships with vividness-related memory qualities, with boredom proneness being associated with a lack of detail and visual imagery, and depression symptoms being associated with more perceived detail and imagery (Fig. 2). This suggests a kind of bland or generic nature to the IAMs experienced by highly boredom prone people; memories that, while recurrent, lack the intensity and complexity of memories experienced by those lower in boredom proneness. Greater perceived detail and imagery with higher depression symptoms also aligns with previous findings, wherein individuals with depression reported their negative intrusive memories as being highly vivid68. Finally, we also observed that depression symptoms were significantly related to a wider range of properties than boredom proneness. It would appear that depression symptoms tended to explain more variance in recurrent IAM phenomenology compared to boredom proneness, which is perhaps unsurprising given the long literature on altered autobiographical memory processes in depression45,50. Though here we focus on the fact that slopes significantly differed for depression symptoms and boredom proneness, future work could explore their relative shares of variance explained.

Content likely plays a role, too. Qualitatively, words associated with high boredom proneness appeared to be more externally focused and related to actions (“do”, “harm”, “wrong”), whereas words associated with depression symptoms appeared to be more internally focused, emotional, and social/communicative (“feel”, “cry”, “say”; Fig. 3). This pattern seems to converge with previous work finding positive correlations between depressive symptoms and episodic details (e.g., emotions felt, persons present) in nonclinical samples69,70,71. To explore content with greater granularity, we used computational text analysis, and showed that boredom proneness and depressive symptoms uniquely predicted the prevalence of different topics in recurrent IAMs. In line with the suggestion that IAMs for the highly boredom prone were somewhat bland, the trait negatively predicted the prevalence of two topics: distressing relationship conflicts and (in the exploratory analysis controlling for valence) pleasant family gatherings. These could be seen as two ends of an affective spectrum, and for the highly boredom prone, neither seems to be a common topic in recurrent IAMs. In contrast, depressive symptoms positively predicted the prevalence of the distressing relationship conflicts topic (Fig. 5). This topic frequently contained descriptions of abuse and may highlight a common proximal correlate of depression.

Interestingly, based on the exploratory analysis controlling for valence (see Supplemental Materials), depressive symptoms also negatively predicted the prevalence of content related to vivid, cued, negative events. At first blush, this seems contradictory to the positive relation between depression symptoms and vividness, as well as the negative relation between depression symptoms and valence (Fig. 2). It may be the case that people with higher depression symptoms feel an event’s emotions intensely, but are less likely to describe it as such when asked (e.g., providing details could itself be triggering of the negative affective experience)72. In addition, it may be the case that individuals with high depressive symptoms are less likely to recollect specific details of memories (as instructed to do here) compared to those with low depressive symptoms. This suggestion is in line with recent work showing that depression is characterized by reduced detail generation when recalling specific events from one’s personal past73,74. So, while those experiencing high depressive symptoms may report recurrent IAMs as being intense, they may be less able (or less willing) to outline the specific content when not explicitly instructed to do so69,72. An interesting point here is that previous studies have observed this pattern with deliberate recall of (hypothetically) voluntary AMs73,74; while the current study also involved deliberate recall (following36,37,75), participants recounted/rated memories that they had previously experienced involuntarily. Although the correspondence between the current and past results is encouraging, future studies could directly compare AMs along the voluntary-involuntary spectrum to shed light on how these different retrieval types relate to depression and boredom proneness.

In sum, the current evidence supports many existing ideas in the literature, including that (a) boredom proneness and depression symptoms are related, but separable constructs, and (b) that recurrent IAMs are associated with a variety of (often unpleasant) affective experiences. Critically, our work advances these ideas by pinpointing specific dimensions along which boredom proneness and depression symptoms have differing, or even opposing, relations. Our findings suggest that the ‘objectless’ nature of boredom proneness can manifest as recurrent IAMs that are less vivid and less likely to be about affectively intense events (e.g., pleasant family gatherings). On the other hand, depression symptoms can manifest as recurrent IAMs that are more frequent, vivid, more likely about negative social events (e.g., distressing relationship conflicts) and less likely about positive social events (e.g., nostalgic trips, family holidays). While boredom proneness and depression symptoms may overlap in many ways, individuals’ memories (e.g., how they are subjectively experienced or reconstructed) can highlight differences in the inner workings of the bored versus depressed mind.

A number of limitations for the current study are also worth noting. First, depression symptoms as measured by the DASS-D (in the past week) may not have aligned temporally with the experience of any given recurrent IAM. Interestingly, our data still suggest that there are consistent relations between recurrent IAMs and depression symptoms despite the scales not being temporally aligned. This suggests that these relationships could be more trait-like or dispositional rather than being dependent on any specific episode of depressive symptoms evoking specific IAMs (or vice versa). Additionally, the correlational nature of this study and its measures means that the current study does not provide causal or directional evidence. Future work could examine the temporal dynamics or directionality of recurrent IAMs, boredom proneness, and depressive symptoms using experience sampling methods.

The present study also only measured participants’ most frequently recurring IAMs (following36,37,75). As such, the recurrent IAM reported by the participant may not be the only one they have. Furthermore, while we asked for their most frequently recurring one, it is possible that participants recalled their most salient (or otherwise accessible) IAM. While our procedure matches prior work36,37 to maintain comparability, this also means that our current findings apply only to participants’ most frequently recurring IAMs, and do not speak to the importance of less frequent ones, nor the relevance of having multiple recurrent IAMs. Future research could determine whether the phenomenology or content of multiple recurrent IAMs within an individual could further differentiate boredom proneness and depression.

We also limited our current analyses to main effects of boredom proneness and depression symptoms. This was motivated by our research questions, which concerned the independent effects of the two variables, and to what extent they converged or diverged in relation to recurrent IAMs. To follow up on the present findings, further studies could examine interactions between boredom proneness and depression symptoms. That is, additional work could investigate whether the observed relationships between recurrent IAMs and boredom proneness also change as a function of depression symptoms (and vice versa).

Another general note is that there is ongoing scholarly discussion about the measurement and divergent validity of boredom proneness and depressive symptoms. While boredom proneness has been consistently positively associated with symptoms of depression, at least one study has used structural equation modeling to convincingly show that the two things are distinct9. Nevertheless, other work has raised concerns regarding just what the Boredom Proneness Scale (and by extension the Short Boredom Proneness Scale) measures76. Future work could make use of more recent measures that overcome these concerns (e.g.,77) to further parse the distinctions between boredom and symptoms of depression.

Overall, we have shown that the phenomenology and content of one’s memories, as reflected in recurrent IAMs, can effectively disambiguate boredom proneness and depression symptoms. By comprehensively examining recurrent IAMs in a large sample, the current study identified specific axes upon which cognition varies as a function of boredom proneness versus depressive symptoms (e.g., external vs. internal focus, vividness, emotional intensity). Our work may open avenues for practitioners to distinguish boredom proneness more easily from depression symptoms, and to examine the circumstances that may explain the relation between the two.

Methods

We report how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions, all manipulations, and all relevant measures in the study.

Participants

Over two years (Sept. 2018–Jan. 2020), 6187 unique undergraduate students who were enrolled in at least one psychology course at the University of Waterloo self-registered for our online study. Participants completed a battery of questionnaires in a randomized order, including the Recurrent Memory Scale, in which they indicated whether they had experienced any recurrent IAMs (i.e., personal memories retrieved unintentionally and repetitively) within the past year. If so, they described their most frequently recurring IAM in text and rated its phenomenology (e.g., frequency of recurring, detail/completeness, visual imagery, valence, and emotional intensity). Participants also completed self-report scales measuring trait boredom proneness and depression symptoms, along with other measures unrelated to the current study. Subsets of the current dataset were previously published in37,42,57.

Our final sample consisted of the 2484 participants who had experienced recurrent IAMs within the past year (nexcluded = 2805), had provided valid text descriptions of recurrent IAMs (i.e., excluding those who wrote meaningless or irrelevant text, using the detection process described in78; nexcluded = 142), and had no missing responses on the scales of interest (e.g., depression symptoms, boredom proneness, recurrent IAM description or phenomenology; nexcluded = 956). Note that participants could have met multiple exclusion criteria (e.g., wrote invalid text and provided no response for at least one item in a scale of interest). Notably, these exclusion rates are quite typical based on prior studies. Past work has shown that approximately 50% of large, nonclinical samples report having not experienced recurrent IAMs in the past year, or ever36,37,38. The number of invalid texts was also comparable to past studies37,57,78. Finally, cases where no response was provided were typical, especially considering that participants tend to skip open text items79.

In our final sample, 71% of participants were women, 28% were men, and 1% were nonbinary, genderqueer, or gender nonconforming. The mean age was 19.9 years (SD = 3.3, range = 16–49). Participants were mostly White/Caucasian (39%), East Asian (23%), or South Asian (19%), and were primarily born in Canada (66%), China (9%), or India (5%; see Supplemental Materials for full breakdown). All procedures were approved by the University of Waterloo’s Office of Research Ethics (Protocol #40049) and informed consent was obtained prior to completing any of the scales. Data and code supporting the results of this study are openly available at: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/83Y2R.

Materials

Recurrent memory scale

We used the Recurrent Memory Scale37 to assess participants’ recurrent IAMs. Participants indicated if they had experienced at least one recurrent IAM within the past year, not within the past year, or never, as instructed by the following prompt adapted from36:

Sometimes, people experience that memories from their personal past may come to mind by themselves. That is, the memory seems to spontaneously pop into mind, effortlessly and without having tried to remember it. Do you experience that the same recollections recurrently pop into your mind by themselves—so that memories for the same event repeat themselves in consciousness? We are not asking about dreams, but about recollections that you experience when you are awake37.

If they had experienced at least one within the past year, they wrote a brief description of their most frequently recurring IAM (Mword count = 32.3, SDword count = 22.2), as instructed by the following prompt: “Please briefly describe your memory of the event in 3–5 sentences, without any identifying information”37. Following the description, they estimated how long ago the original event occurred (Myears ago = 3.8, SDyears ago = 4.9) and rated the memory’s phenomenology on a series of 5-point Likert scales. Of interest in the current study were the items measuring frequency of recurring (“How often within the most recent year have you experienced that same recollection returning to your thoughts by itself?”; 1 = only once, 5 = several times a day), detail/completeness (“How complete and detailed is your memory for the event?”; 1 = not complete or detailed, 5 = very complete and detailed), vividness of visual imagery (“If you experience visual images of the event when remembering it, how vivid are these images?”; 1 = cloudy or no image at all, 5 = as vivid as normal vision), valence (“Is the recollection emotionally very positive, positive, neutral, negative, or very negative?”; -2 = very negative, 2 = very positive), and emotional intensity (“Is the recollection emotionally not at all intense, a little intense, somewhat intense, intense, or very intense?”; 1 = not at all intense, 5 = very intense).

Depression anxiety stress scales

We administered the DASS-2180 to assess depression symptoms, as indexed by the 7-item depression subscale (DASS-D). Participants indicated the degree to which the items applied to them over the past week. Internal consistency was high in the current sample for the full scale (α = 0.96), as well as the depression subscale (α = 0.94).

Short boredom proneness scale

We administered the SBPS7 to assess boredom proneness, which consists of eight items indexing the tendency to experience boredom. Internal consistency was high in the current sample (α = 0.88).

Text analysis

Supervised dimension projection

We first sought to provide a visual depiction of memory content as a function depression symptoms and boredom proneness. To do so, we constructed a supervised dimension projection plot81 for participants’ text descriptions of their recurrent IAMs. In brief, this method uses word embeddings to identify words that are significantly related to high versus low scorers on variables of interest (i.e., depression symptoms and boredom proneness). Text data were tokenized, cleaned (e.g., punctuation removal), and lemmatized before we constructed word embeddings using the pretrained RoBERTa model.

For visual inspection purposes, we also created word clouds of terms used relatively more frequently by those high in depression symptoms versus those high in boredom proneness (i.e., those scoring in the top tertile of one, but not the other; Fig. S2), or those high in both (i.e., those scoring in the top tertile of both; Fig. S3; see Supplemental Materials).

Topic modeling

To formally analyze content of recurrent IAMs beyond the level of single words, we then used structural topic modeling60—a method of unsupervised machine learning—to identify topics in participants’ memories and examine the unique relationships between these topics and both boredom proneness and depression symptoms. Topic modeling also offers benefits in terms of word sense disambiguation or polysemy (words having the same spelling but different meanings, e.g., “bat” as in “baseball bat” versus “fruit bat”), since words can be assigned to different topics if they consistently appear in different contexts82.

Typical topic modeling procedures are reported elsewhere in detail57. To summarize, we applied standard preprocessing steps83,84, including tokenization, cleaning (e.g., removing punctuation), stop word removal (using the Snowball stop word list), vocabulary pruning (excluding words that appeared in fewer than three documents across the entire corpus), and lemmatization. Researchers must also select an a priori number of topics (i.e., groups of words that can be interpreted as themes)60,61 to be identified when using structural topic modeling60. To select an appropriate number of topics, we simulated and inspected models with the same parameters (e.g., covariates) across a varying number of topics (i.e., between 5 and 25 topics). We then selected an appropriate number of topics using a two-stage approach85.

First, internal validation (based on computed metrics derived from the data) guided the initial selection of candidate models. Following60, metrics were computed for each possible model (i.e., number of topics), including semantic coherence (degree to which words within a topic co-occur more so than words across different topics)86, exclusivity (degree to which words are specific to few topics versus general across many topics)87, and held-out likelihood (“probability of words appearing within a document when those words have been removed from the document in the estimation step”)88 (p. 38). Local maxima for semantic coherence, exclusivity, and held-out likelihood values were found at 11, 15, and 21 topics; accordingly, we chose these three as candidate models (Fig. 6).

Accuracy and observed coherence in word intrusion task by topic number. Responses during the word intrusion task, separated into intruder detection accuracy (A) and observed coherence ratings (B). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Dashed line in (A) indicates chance performance. Grey points indicate individual participants’ data, with grey lines between points indicating data points from the same participants. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. All other comparisons were nonsignificant (ps > 0.051).

Second, external validation (based on human judgment and performance measures) guided the selection of the final model from the three candidate models. This entailed administering a word intrusion task89 to ten independent raters who were naïve to the goals and hypotheses of the study (all raters were research assistants in the labs of authors JD, WvT, and MF). On each trial, raters saw sets of six words. Unbeknownst to the raters, five of the words were highly representative (highest five frequency-exclusivity scores)87 of one topic (e.g., “car, “pass”, “accident”, “crash”, “drive”), while the remaining word was highly representative (sixth highest frequency-exclusivity score) of a different, randomly selected topic (e.g., “class”). Raters were asked to identify the word that did not belong (i.e., the intruder or word from the different topic), with successful intruder detection being interpreted as better model quality83. Following this judgment, raters were shown the five words belonging to the same topic and rated the degree to which they seemed to cohere (i.e., observed coherence; from 1 = very incoherent to 5 = very coherent)89. Comparing intrusion detection accuracy and observed coherence across the three candidate models (11, 15, 21 topics), ANOVAs and post hoc Tukey tests indicated preference for the 15-topic model as the final model (Fig. 6; also see Supplemental Materials).

A deliberation process was then conducted to generate researcher-assigned labels characterizing each topic in the final model57,84,85. Each author was provided with the top ten most representative words for each topic, twenty documents (i.e., IAMs reported by participants) predicted to contain the highest proportions of each topic, and other internal, computationally derived metrics (e.g., coherence, exclusivity). Using this information, all authors generated labels independently before meeting to agree on labels. Agreement on the independently generated labels was high; all 15 topics were independently assigned labels that matched across at least 50% of the authors, even before discussion (100% agreement for nine topics, 75% agreement for four topics, 50% agreement for two topics; Table 2).

Data availability

Data and code supporting the results of this study are openly available at: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/83Y2R.

References

Eastwood, J. D., Frischen, A., Fenske, M. J. & Smilek, D. The unengaged mind: Defining boredom in terms of attention. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 7(5), 482–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612456044 (2012).

Bench, S. W. & Lench, H. C. On the function of boredom. Behav. Sci. 3(3), 459–472. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs3030459 (2013).

Tam, K. Y., van Tilburg, W. A. & Chan, C. S. What is boredom proneness? A comparison of three characterizations. J. Pers. 89(4), 831–846. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12618 (2021).

Danckert, J., Mugon, J., Struk, A. & Eastwood, J. Boredom: What is It Good For? In The Function of Emotions 93–119 (Springer, 2018).

Farmer, R. & Sundberg, N. D. Boredom proneness: The development and correlates of a new scale. J. Pers. Assess. 50(1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5001_2 (1986).

Lee, F. K. & Zelman, D. C. Boredom proneness as a predictor of depression, anxiety and stress: The moderating effects of dispositional mindfulness. Pers. Individ. Diff. 146, 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.04.001 (2019).

Struk, A. A., Carriere, J. S., Cheyne, J. A. & Danckert, J. A short boredom proneness scale: Development and psychometric properties. Assessment 24(3), 346–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191115609996 (2017).

Van Tilburg, W. A. P. & Igou, E. R. Boredom begs to differ: Differentiation from other negative emotions. Emotion 17(2), 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000233 (2017).

Goldberg, Y. K., Eastwood, J. D., LaGuardia, J. & Danckert, J. Boredom: An emotional experience distinct from apathy, anhedonia, or depression. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 30(6), 647. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2011.30.6.647 (2011).

Hunter, A. & Eastwood, J. D. Does state boredom cause failures of attention? Examining the relations between trait boredom, state boredom, and sustained attention. Exp. Brain Res. 236(9), 2483–2492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-016-4749-7 (2018).

LeMoult, J. & Gotlib, I. H. Depression: A cognitive perspective. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 69, 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.06.008 (2019).

Pekrun, R. et al. A three-dimensional taxonomy of achievement emotions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 124(1), 145–178. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000448 (2023).

Isacescu, J., Struk, A. A. & Danckert, J. Cognitive and affective predictors of boredom proneness. Cogn. Emot. 31(8), 1741–1748. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1259995 (2017).

Van Tilburg, W. A. P. & Igou, E. R. On boredom and social identity: A pragmatic meaning-regulation approach. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 37, 1679–1691. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211418530 (2011).

Hedayati, M. M. & Khazaei, M. M. An investigation of the relationship between depression, meaning in life and adult hope. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 114, 598–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.753 (2014).

Bruursema, K., Kessler, S. R. & Spector, P. E. Bored employees misbehaving: The relationship between boredom and counterproductive work behaviour. Work Stress 25(2), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2011.596670 (2011).

Girard, J. M. et al. Nonverbal social withdrawal in depression: Evidence from manual and automatic analyses. Image Vis. Comput. 32(10), 641–647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imavis.2013.12.007 (2014).

Kearney, C. A. School absenteeism and school refusal behavior in youth: A contemporary review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 28(3), 451–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.012 (2008).

van Hooff, M. L. & van Hooft, E. A. Boredom at work: Proximal and distal consequences of affective work-related boredom. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 19(3), 348–359. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036821 (2014).

Freund, V. A., Schulenberg, J. E. & Maslowsky, J. Boredom by sensation-seeking interactions during adolescence: Associations with substance use, externalizing behavior, and internalizing symptoms in a US national sample. Prev. Sci. 22, 555–566. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01198-0 (2021).

Swendsen, J. D. & Merikangas, K. R. The comorbidity of depression and substance use disorders. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 20(2), 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00026-4 (2000).

Moynihan, A. B., Igou, E. R. & van Tilburg, W. A. P. Boredom increases impulsiveness. Soc. Psychol. 48(5), 293–309. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000317 (2017).

Yu, Y., Yu, Y. & Lin, Y. Anxiety and depression aggravate impulsiveness: The mediating and moderating role of cognitive flexibility. Psychol. Health Med. 25(1), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2019.1601748 (2020).

Treadway, M. T. & Zald, D. H. Reconsidering anhedonia in depression: Lessons from translational neuroscience. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 35(3), 537–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.06.006 (2011).

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E. & Lyubomirsky, S. Rethinking rumination. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 3(5), 400–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x (2008).

Wang, Y., Yang, H., Montag, C. & Elhai, J. D. Boredom proneness and rumination mediate relationships between depression and anxiety with problematic smartphone use severity. Curr. Psychol. 1, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01052-0 (2020).

Mugon, J., Struk, A. & Danckert, J. A failure to launch: Regulatory modes and boredom proneness. Front. Psychol. 9(1126), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01126 (2018).

Bargdill, R. W. Habitual boredom and depression: Some qualitative differences. J. Hum. Psychol. 59(2), 294–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167816637948 (2019).

Pekrun, R. The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 18, 315–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9029-9 (2006).

Chin, A., Markey, A., Bhargava, S., Kassam, K. S. & Loewenstein, G. Bored in the USA: Experience sampling and boredom in everyday life. Emotion 17, 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000232 (2017).

Bargdill, R. W. A phenomenological investigation of being bored with life. Psychol. Rep. 86, 493–494. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.2000.86.2.493 (2000).

Tam, K. Y., van Tilburg, W. A. P., Chan, C. S., Igou, E. R. & Lau, H. Attention drifting in and out: The boredom feedback model. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 25(3), 251–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/10888683211010297 (2021).

Tam, K. Y., Chan, C. S., Van Tilburg, W. A. P., Lavi, I. & Lau, J. Y. Boredom belief moderates the mental health impact of boredom among young people: Correlational and multi-wave longitudinal evidence gathered during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Pers. 91(3), 638–652. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12764 (2023).

Bargdill, R. W. Toward a theory of habitual boredom. Janus Head 13(2), 93–111. https://doi.org/10.5840/jh201413219 (2014).

Berntsen, D. Involuntary autobiographical memories. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 10(5), 435–454. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0720(199610)10:5%3c435::AID-ACP408%3e3.0.CO;2-L (1996).

Berntsen, D. & Rubin, D. C. The reappearance hypothesis revisited: Recurrent involuntary memories after traumatic events and in everyday life. Mem. Cogn. 36(2), 449–460. https://doi.org/10.3758/mc.36.2.449 (2008).

Yeung, R. C. & Fernandes, M. A. Recurrent involuntary autobiographical memories: Characteristics and links to mental health status. Memory 28(6), 753–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2020.177731 (2020).

Yeung, R. C. & Fernandes, M. A. Recurrent involuntary memories are modulated by age and linked to mental health. Psychol. Aging 36(7), 883–890. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000630 (2021).

Brewin, C. R., Gregory, J. D., Lipton, M. & Burgess, N. Intrusive images in psychological disorders: Characteristics, neural mechanisms, and treatment implications. Psychol. Rev. 117(1), 210–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018113 (2010).

Marks, E. H., Franklin, A. R. & Zoellner, L. A. Can’t get it out of my mind: A systematic review of predictors of intrusive memories of distressing events. Psychol. Bull. 144(6), 584–640. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000132 (2018).

Payne, A., Kralj, A., Young, J. & Meiser-Stedman, R. The prevalence of intrusive memories in adult depression: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 253, 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.055 (2019).

Yeung, R. C. & Fernandes, M. A. Specific topics, specific symptoms: Linking the content of recurrent involuntary memories to mental health using computational text analysis. NPJ Mental Health Res. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-023-00042-x (2023).

Berntsen, D. & Hall, N. M. The episodic nature of involuntary autobiographical memories. Mem. Cogn. 32(5), 789–803. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03195869 (2004).

Marchetti, I., Koster, E. H., Klinger, E. & Alloy, L. B. Spontaneous thought and vulnerability to mood disorders: The dark side of the wandering mind. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 4(5), 835–857. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702615622383 (2016).

Holmes, E. A., Blackwell, S. E., Burnett Heyes, S., Renner, F. & Raes, F. Mental imagery in depression: Phenomenology, potential mechanisms, and treatment implications. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 12, 249–280. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-092925 (2016).

Rasmussen, A. S., Ramsgaard, S. B. & Berntsen, D. Frequency and functions of involuntary and voluntary autobiographical memories across the day. Psychol. Conscious. Theor. Res. Pract. 2(2), 185–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/cns0000042 (2015).

Branch, J. G. Individual differences in the frequency of voluntary & involuntary episodic memories, future thoughts, and counterfactual thoughts. Psychol. Res. 1, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-023-01802-2 (2023).

Blondé, P., Girardeau, J. C., Sperduti, M. & Piolino, P. A wandering mind is a forgetful mind: A systematic review on the influence of mind wandering on episodic memory encoding. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 132, 774–792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.11.015 (2022).

Plimpton, B., Patel, P. & Kvavilashvili, L. Role of triggers and dysphoria in mind-wandering about past, present and future: A laboratory study. Conscious. Cogn. 33, 261–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2015.01.014 (2015).

Gotlib, I. H. & Joormann, J. Cognition and depression: Current status and future directions. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 6, 285–312. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131305 (2010).

Van Tilburg, W. A. P. & Igou, E. R. On boredom: Lack of challenge and meaning as distinct boredom experiences. Motiv. Emot. 36, 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-011-9234-9 (2012).

Johnson, M. K., Foley, M. A., Suengas, A. G. & Raye, C. L. Phenomenal characteristics of memories for perceived and imagined autobiographical events. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 117(4), 371–376. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.117.4.371 (1988).

Rubin, D. C. Properties of autobiographical memories are reliable and stable individual differences. Cognition 210, 104583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2021.104583 (2021).

Reynolds, M. & Brewin, C. R. Intrusive memories in depression and posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 37(3), 201–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00132-6 (1999).

Watt, J. D. & Blanchard, M. J. Boredom proneness and the need for cognition. J. Res. Pers. 28(1), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1994.1005 (1994).

Kopelman, M. D., Wilson, B. A. & Baddeley, A. D. The autobiographical memory interview: A new assessment of autobiographical and personal semantic memory in amnesic patients. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 11(5), 724–744 (1989).

Yeung, R. C., Stastna, M. & Fernandes, M. A. Understanding autobiographical memory content using computational text analysis. Memory 30(10), 1267–1287. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2022.2104317 (2022).

Williams, A. D. & Moulds, M. L. An investigation of the cognitive and experiential features of intrusive memories in depression. Memory 15(8), 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210701508369 (2007).

Liu, T. et al. Head versus heart: Social media reveals differential language of loneliness from depression. NPJ Mental Health Res. 1(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-022-00014-7 (2022).

Roberts, M. E. et al. Structural topic models for open-ended survey responses. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 58(4), 1064–1082. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12103 (2014).

Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y. & Jordan, M. I. Latent Dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 3, 993–1022 (2003).

Paternoster, R., Brame, R., Mazerolle, P. & Piquero, A. Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology 36(4), 859–866. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1998.tb01268.x (1998).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 57(1), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x (1995).

Van Tilburg, W. A. P., Pekrun, R. & Igou, E. R. Consumed by boredom: Food choice motivations and weight changes. Behav. Sci. 12(10), 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100366 (2022).

Erzen, E. & Çikrikci, Ö. The effect of loneliness on depression: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 64(5), 427–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764018776349 (2018).

Blaszczynski, A., McConaghy, N. & Frankova, A. Boredom proneness in pathological gambling. Psychol. Rep. 67, 35–42. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1990.67.1.35 (1990).

Ben-Zeev, D., Young, M. A. & Depp, C. A. Real-time predictors of suicidal ideation: Mobile assessment of hospitalized depressed patients. Psychiatry Res. 197(1–2), 55–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.11.025 (2012).

Newby, J. M. & Moulds, M. L. Characteristics of intrusive memories in a community sample of depressed, recovered depressed and never-depressed individuals. Behav. Res. Ther. 49(4), 234–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.01.003 (2011).

Barry, T. J. et al. Autobiographical memory and psychopathology: Is memory specificity as important as we make it seem?. WIREs Cogn. Sci. 14(3), 1624. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1624 (2023).

Kyung, Y., Yanes-Lukin, P. & Roberts, J. E. Specificity and detail in autobiographical memory: Same or different constructs?. Memory 24(2), 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2014.1002411 (2015).

Salmon, K. et al. Delving into the detail: Greater episodic detail in narratives of a critical life event predicts an increase in adolescent depressive symptoms across one year. Behav. Res. Ther. 137, 103798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2020.103798 (2021).

Adler, J. M. et al. Research methods for studying narrative identity. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 8(5), 519–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617698202 (2017).

Barry, T. J., Hallford, D. J. & Takano, K. Autobiographical memory impairments as a transdiagnostic feature of mental illness: A meta-analytic review of investigations into autobiographical memory specificity and overgenerality among people with psychiatric diagnoses. Psychol. Bull. 147(10), 1054–1074. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000345 (2021).

Hallford, D. J. et al. Specificity and detail in autobiographical memory retrieval: A multi-site (re)investigation. Memory 29(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2020.1838548 (2021).

Yoshizumi, T. & Murase, S. The effect of avoidant tendencies on the intensity of intrusive memories in a community sample of college students. Pers. Individ. Diff. 43(7), 1819–1828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.05.019 (2007).

Gana, K., Broc, G. & Bailly, N. Does the boredom proneness scale capture traitness of boredom? Results from a six-year longitudinal trait-state-occasion model. Pers. Individ. Diff. 139, 247–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.11.030 (2019).

Gorelik, D. & Eastwood, J. D. Trait boredom as a lack of agency: A theoretical model and a new assessment tool. Assessment https://doi.org/10.1177/10731911231161780 (2023).

Yeung, R. C. & Fernandes, M. A. Machine learning to detect invalid text responses: Validation and comparison to existing detection methods. Behav. Res. Methods 54, 3055–3070. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-022-01801-y (2022).

Reja, U., Manfreda, K. L., Hlebec, V. & Vehovar, V. Open-ended vs. close-ended questions in web questionnaires. In Developments in Applied Statistics (eds Ferligoj, A. & Mrva, A.) 159–177 (University of Ljubljana, 2003).

Lovibond, P. F. & Lovibond, S. H. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u (1995).

Kjell, O., Giorgi, S. & Schwartz, H. A. The text-package: An R-package for analyzing and visualizing human language using natural language processing and transformers. Psychol. Methods https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000542 (2023).

Steyvers, M. & Griffiths, T. Probabilistic topic models. In Handbook of Latent Semantic Analysis (eds Landauer, T. K. et al.) 439–460 (Psychology Press, 2007). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203936399.ch21.

Maier, D., Niekler, A., Wiedemann, G. & Stoltenberg, D. How document sampling and vocabulary pruning affect the results of topic models. Comput. Commun. Res. 2(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.5117/CCR2020.2.001.MAIE (2020).

Maier, D. et al. Applying LDA topic modeling in communication research: Toward a valid and reliable methodology. Commun. Methods Meas. 12(2–3), 93–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2018.1430754 (2018).

Grimmer, J. & Stewart, B. M. Text as data: The promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Polit. Anal. 21(3), 267–297. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mps028 (2013).

Mimno, D., Wallach, H., Talley, E., Leenders, M., & McCallum, A. (2011). Optimizing semantic coherence in topic models. in Proceedings of the 2011 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 262–272.

Bischof, J. M., & Airoldi, E. M. (2012). Summarizing topical content with word frequency and exclusivity. in Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML ‘12), 9–16.

Roberts, M. E., Stewart, B. M. & Tingley, D. stm: An R package for structural topic models. J. Stat. Softw. 91, 1–40. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v091.i02 (2019).

Lau, J. H., Newman, D., & Baldwin, T. (2014). Machine reading tea leaves: Automatically evaluating topic coherence and topic model quality. in Proceedings of the 14th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 530–539. https://doi.org/10.3115/v1/E14-1056.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) through an Alexander Graham Bell Canada Graduate Scholarship (CGSD3-535024-2019) and Postdoctoral Fellowship (PDF-578187-2023) awarded to author RY, and an NSERC Discovery Grant (2020-03917) awarded to author MF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.Y., M.F., J.D., and W.v.T. conceptualized the study, R.Y. collected data, conducted analyses and created the figures, M.F. provided resources and supervision. All authors co-wrote, edited, and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yeung, R.C., Danckert, J., van Tilburg, W.A.P. et al. Disentangling boredom from depression using the phenomenology and content of involuntary autobiographical memories. Sci Rep 14, 2106 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52495-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52495-5

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.