Abstract

To investigate the relationship between metabolic syndrome (MS) and postoperative complications in Chinese adults after open pancreatic surgery. Relevant data were retrieved from the Medical system database of Changhai hospital (MDCH). All patients who underwent pancreatectomy from January 2017 to May 2019 were included, and relevant data were collected and analyzed. A propensity score matching (PSM) and a multivariate generalized estimating equation were used to investigate the association between MS and composite compositions during hospitalization. Cox regression model was employed for survival analysis. 1481 patients were finally eligible for this analysis. According to diagnostic criteria of Chinese MS, 235 patients were defined as MS, and the other 1246 patients were controls. After PSM, no association was found between MS and postoperative composite complications (OR: 0.958, 95%CI: 0.715–1.282, P = 0.958). But MS was associated with postoperative acute kidney injury (OR: 1.730, 95%CI: 1.050–2.849, P = 0.031). Postoperative AKI was associated with mortality in 30 and 90 days after surgery (P < 0.001). MS is not an independent risk factor correlated with postoperative composite complications after open pancreatic surgery. But MS is an independent risk factor for postoperative AKI of pancreatic surgery in Chinese population, and AKI is associated with survival after surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the American Cancer Society, pancreatic cancer is predicted to remain the second leading cause of cancer deaths within the next decade1. Both the incidence and death rates of pancreatic cancer are increasing globally2. Surgery remains the only option which could offer curative potential for pancreatic patients3,4,5. However, complications after pancreatic surgery frequently reported and considerably associated with mortality or severe clinical outcome6,7. Identifying the potential risk factors for postoperative complications is the first challenge for the prevention.

Metabolic syndrome (MS) is a syndrome involving a variety of metabolic disorders, and a predictor of several diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, osteoarthritis, and certain cancers8. The association between MS and postoperative complications after pancreatic surgery are still largely unclear and currently, only a limited number of studies have analyzed this association, showing a debating result. Some studies suggested that MS9 and its components like obesity10, diabetes11,12 and hypertension13 would increase the risk of medical complications14,15,16, overall and cancer-specific mortality17. Additionally, only a few of them concentrated on open pancreatic cancer surgery with controversial conclusions10,18,19,20.

According to previous studies, the prevalence and clinical diagnostic criteria of MS were different in races9,17,21,22. Notably, the diagnostic criteria of BMI adopted in MS for Chinese is lower than that for the Whites, which might have impact on postoperative complications after pancreatic surgery. Therefore, studies only adopted universal criteria for all race for small portion of Chinese population were not exactly correct18,19. This study examined a large group of Chinese patients hospitalized with pancreatic cancer who had underwent open pancreatic cancer surgery to determine if MS was associated with postoperative complications.

Methods

Data collection and study design

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standard specified by national health commission of China (Act 11, 2016) and approved by the ethics committee of Changhai Hospital (CHEC2020-170). The requirement for written informed consent was waived by the ethics committee. The clinical registration number is ChiCTR2000031167 (available on http://www.chictr.org.cn/). This study retrieved the medical records of elective pancreatectomies in Changhai Hospital from January 2017 to May 2019.

For the eligible patients in this study, relevant information was retrieved: descriptive and surgical information; diagnostic information of metabolic syndrome; information of complications during hospitalization; prognosis during hospitalization. Telephone follow-ups were made after data collections.

Diagnosis of MS

The diagnosis of metabolic syndrome is defined on recommendations of Chinese Diabetes Society17: (1) Overweight and (or) obesity, BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2; (2) Hyperglycemia, fasting blood glucose (FPG) ≥ 6.1 mmol/l (110 mg/dl) and (or) 2 h PG ≥ 7.8 mmol/l (140 mg/dl), and (or) diabetes mellitus diagnosed and treated; (3) Hypertension, systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg, and (or) hypertension diagnosed and treated; (4) Dyslipidemia, fasting blood triglyceride ≥ 1.7 mmol/L (150 mg/dl), and/or fasting blood HDL-C < 0.9 mmol/L (35 mg/dl) for male and < 1.0 mmol/L (39 mg/dl) for female. Patients qualified 3 or more of the above 4 components will be diagnosed as MS.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Our primary outcome was the correlation of composite complications (CC) with MS. A composite of postoperative complications defining as the overall occurrence of any symptoms of the following five components during hospitalization: (1) cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (CCE), (2) non-pulmonary postoperative infection (NPPI), (3) pulmonary complications (PC), (4) complications requiring surgical intervention (CRSI), and (5) postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI). CCE included myocardial infarction, heart failure, cardiac arrest, stroke, and pulmonary embolism. NPPI were differentiated according to the location or system, such as superficial wound infection, pancreatic fistula, surgical incision, abdominal infection, urinary infection, systemic infection. PC10 included pulmonary infection, atelectasis, pneumothorax, hemothorax, pleural effusion and respiratory related hypoxemia. Postoperative AKI was defined as a categorical variable according to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes work group, as any increase in postoperative serum creatinine of 0.3 mg/dL or more (to convert to micromoles per liter, multiply by 88.4) or a 50% increase from preoperative baseline serum creatinine level. The Cockcroft–Gault equation was adopted for eGFR evaluation, depending on patients’ gender. Secondary outcome were correlations of components of CC with MS and prognosis of complications.

Statistical analysis

A propensity score matching (PSM) was performed at a 1:4 fixed ratio nearest-neighbor matching to control for bias from covariates including gender, preoperative biliary stented, and the operation method. The caliper value was 0.2. The normality of data distribution was tested by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation or medians (IQR), as appropriate for the data distribution. Group differences were assessed by ANOVA test or Mann–Whitney U tests. Categorical variables were expressed as the number of cases or the percentages (%). Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests were adopted for assessing the differences between groups. Given that incidences varied considerably across the four components. For the primary hypothesis that MS patients have increased risk for postoperative complications, a multivariate distinct effect generalized estimating equations model with an unstructured working correlation was employed and the odds ratios (ORs) across the five components were assessed. Binary logistic regression was selected to fit the regression model. Results were reported as a covariate-adjusted OR and its 95% confidence interval (CI) that summarizing the relationship between MS and postoperative composite complications at the 0.05 significance level. Cox regression model was used to analyze the survival of patients within 30 and 90 days after operation. A two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered to be significant. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics v21 (IBM Corporation, NY, USA) or RStudio (version 4.1.3).

Results

Characteristic data and outcomes in hospital

After screening, there were 3265 patients who had pancreatic cancer during the studied period, of whom, 2415 patients met the inclusion criteria and had complete clinical information. After excluding 585 patients who did not receive pancreatic surgery, 256 patients who had tumor metastasis, 15 patients whose were aged under 18, 44 patients underwent total pancreatectomy, and 34 patients were lost of follow-ups, a total of 235 MS patients and 1246 non-MS patients were analyzed in this study (Fig. 1). After the PSM, there were a total of 1163 patients finally left in the study cohort (MS group = 235, control group = 928).

Patients’ characteristics were summarized in Table 1. After PSM, in addition to the diagnostic inclusion of metabolic syndrome, age and ASA were statistically different between the two groups.

After PSM, intravenous infusion rate, and the volume of perioperative bleeding were significantly different between the two groups (P < 0.001, Table 2).

Composite complications

The ORs of MS on postoperative complications after pancreatic surgery were illustrated in Table 3. After PSM, the occurrence of postoperative AKI was significantly different between the two groups (OR: 1.730, 95%CI: 1.050–2.849, P = 0.031), and difference in the postoperative composite complications between patients with and those without MS were not different (OR: 1.116, 95%CI: 0.808–1.542, P = 0.504). No other postoperative component was found to be significantly different in patients with or without MS (P > 0.05).

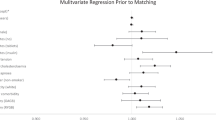

The association between each covariate and MS with the postoperative composite complications were summarized in Table 4. After PSM, the results showed patients who underwent partial pancreatectomy had a lower risk of postoperative CC compared to those who underwent pancreatoduodenectomy (OR: 0.524, 95%CI: 0.366–0.752, P < 0.001). A younger age (OR: 0.980, 95%CI: 0.968–0.993, P = 0.002) and a shorter operation time (OR: 0.792, 95%CI: 0.689–0.911, P = 0.001) were also factors that reduce postoperative CC.

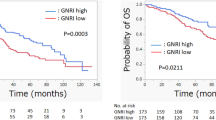

Survival analysis

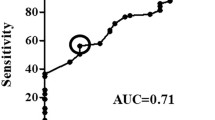

CCE, AKI, and CSRI were significantly associated with both 30-day and 90-day mortality in multivariate cox regression, whereas PC was only significantly associated with 90-day mortality (All P < 0.001). The detailed data of multivariate COX regression were shown in Table 5. Cox survival curves of CCE, AKI and CSRI were illustrated in Fig. 2.

Overall correlations between the outcomes within 30 and 90 days after the surgery and MS, CC and their components were illustrated in Fig. 3.

Overall correlations between outcomes and MS or CC and their components. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01,*P < 0.05. (A) 30-day spearman results; (B) 90-day spearman results. MS: Metabolic syndrome; HT: hypertension; DM: diabetes mellitus; DL: dyslipidemia; OO: overweight or obesity; CCE: cardiovascular and cerebrovascular event; PC: pulmonary complications; AKI: Acute Kidney Injury; NPPI: non-pulmonary postoperative infection; CRSI: complications requiring surgical intervention; CC: composite complications.

Discussion

Although the diagnostic criteria for MS adopted differently, the percentage of MS patients in pancreatic cancer (15.9%) was consistent with the previous studies (11–24%)18,23.

Postoperative complications of pancreatic surgeries were complex9,24. After PSM, GEE was employed to analyze the overall complications without discussing the distribution form of dependent variables, which fits a marginal model in the context of longitudinal studies25,26. There were no significant association between MS and postoperative composite complications after open pancreatic surgery (OR = 0.958, 95%CI: 0.715–1.282, P = 0.771). It indicated that MS did not increase the overall risk in postoperative complications after pancreatic surgery independently.

The conclusion of our analysis was consistent with some studies18,27. However, May C Tee et al. reported that MS patients who received selective pancreatic surgery had an increased risk of postoperative morbidity and some complications9. It inferred that MS may increase some certain complications.

In our results, AKI was significantly associated with MS after PSM (OR: 1.730, 95%CI: 1.050–2.849, P = 0.031). Several studies on cardiac surgery have indicated that MS patients were associated with increased rates of postoperative morbidity, infections, cardiovascular and renal adverse events14,15,16. Congruently, our research demonstrated that MS patients was susceptible to postoperative AKI after pancreatic surgery.

MS components such as obesity, hypertension, elevated TG, low HDL-C, impaired fasting glucose, and MS per se were contributed to decreased GFR28. The Chinese Diabetes Society (CDS) diagnostic criteria of MS adopted a relatively smaller BMI standard (BMI ≥ 25) for Chinese population compared to the western population. The smaller BMI did not prevent occurrence of AKI, although there is a possibility that the risk of postoperative AKI after non-cardiac surgery would be increased with severity of obesity29.

Intraoperative fluid therapy may affect postoperative AKI. Restrict fluid therapy was not used in our center for the pancreatic surgery (in Table 2). According to the previous studies that restricted infusion is more likely to cause postoperative AKI, the statistical differences in intraoperative fluid therapy may not be the key point for AKI30. Multivariate regression analysis showed that intraoperative bleeding was an independent risk factor for postoperative AKI compared with intraoperative volume management (in Supplementary table). It was suggested that strategies to reduce intraoperative bleeding may help to reduce AKI after pancreatic surgery.

Although NPPI accounted for 80% of CC and all complications were associated with outcomes in the spearman analysis, only CCE, AKI and CRSI were associated with survival within 30 and 90 days of surgery after multivariate Cox proportional hazards model analysis. It was implicated that the effective prevention of CCE, AKI and CRSI after pancreatic surgery is helpful to reduce postoperative mortality rate. They require more attention from anesthesiologists and surgeons due to their impact on 30-day and 90-day mortality following pancreatic surgery. Because AKI is more susceptible and increases perioperative mortality for MS patients after the pancreatic surgery. It indicated that MS patients received pancreatic surgery should be paid more attention to postoperative AKI for both anesthesiologists and surgeons.

There are several limits in this study. Firstly, this is a single-centered retrospective study, which largely limited the quality of prognosis. But fortunately, our center is a high volume of pancreatic center, and patients received from all over the country. Because the study is based on Chinese diagnostic criteria, patients across the country can provide a certain degree of reference. Secondly, the definition of MS adopted in this study relied on the CDS criteria published in 2004 exclusively characterized for Chinese population31, which might inherently differentiate the characteristics of our patients from those in previous studies. Yet the influence of different diagnostic criteria for MS on postoperative complications is our study.

In conclusion, we observed that MS patients who received open pancreatic surgery had no association with postoperative composite complications during hospitalization. But MS is an independent risk factor for postoperative AKI of pancreatic surgery in Chinese population. And AKI was associated with perioperative survival of MS.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from Dryad Digital Repository (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.bcc2fqzdz) and can be temporarily visited by https://datadryad.org/stash/share/OEWZ_1qNX9ijRMg86tHeNUUJiOIBLiOkoRc4sCGcKQs.

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 7–33 (2021).

GBD 2017 Pancreatic Cancer Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of pancreatic cancer and its attributable risk factors in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 4, 934–947 (2017).

Ma, J., Siegel, R. & Jemal, A. Pancreatic cancer death rates by race among US men and women, 1970–2009. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 105, 1694–1700 (2013).

Mizrahi, J. D., Surana, R., Valle, J. W. & Shroff, R. T. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 395, 2008–2020 (2020).

Okasha, H. et al. Real time endoscopic ultrasound elastography and strain ratio in the diagnosis of solid pancreatic lesions. World J. Gastroenterol. 23, 5962–5968 (2017).

Vollmer, C. M. Jr. et al. A root-cause analysis of mortality following major pancreatectomy. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 16, 89–102 (2012) (discussion 102-103).

Kelly, K. J. et al. Risk stratification for distal pancreatectomy utilizing ACS-NSQIP: Preoperative factors predict morbidity and mortality. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 15, 250–259 (2011) (discussion 259-261).

Rosato, V. et al. Metabolic syndrome and pancreatic cancer risk: A case-control study in Italy and meta-analysis. Metabolism 60, 1372–1378 (2011).

Tee, M. C. et al. Metabolic syndrome is associated with increased postoperative morbidity and hospital resource utilization in patients undergoing elective pancreatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 20, 189–198 (2016) (discussion 198).

Chang, E. H. et al. Obesity and surgical complications of pancreaticoduodenectomy: An observation study utilizing ACS NSQIP. Am. J. Surg. 220, 135–139 (2020).

Tan, D. J. H. et al. The influence of diabetes on postoperative complications following colorectal surgery. Tech. Coloproctol 25, 267–278 (2021).

Gu, A. et al. Postoperative complications and impact of diabetes mellitus severity on revision total knee arthroplasty. J. Knee Surg. 33, 228–234 (2020).

Sánchez-Guillén, L. et al. Risk factors for leak, complications and mortality after ileocolic anastomosis: Comparison of two anastomotic techniques. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 101, 571–578 (2019).

Echahidi, N. et al. Metabolic syndrome increases operative mortality in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 50, 843–851 (2007).

Tzimas, P. et al. Impact of metabolic syndrome in surgical patients: Should we bother?. Br. J. Anaesth. 115, 194–202 (2015).

Hong, S., Youn, Y. N. & Yoo, K. J. Metabolic syndrome as a risk factor for postoperative kidney injury after off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery. Circ. J. 74, 1121–1126 (2010).

Zhou, H. et al. Evidence on the applicability of the ATPIII, IDF and CDS metabolic syndrome diagnostic criteria to identify CVD and T2DM in the Chinese population from a 6.3-year cohort study in mid-eastern China. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 90, 319–325 (2010).

Le Bian, A. Z. et al. Consequences of metabolic syndrome on postoperative outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J. Gastroenterol. 23, 3142–3149 (2017).

Raviv, N. V., Sakhuja, S., Schlachter, M. & Akinyemiju, T. Metabolic syndrome and in-hospital outcomes among pancreatic cancer patients. Diabetes Metab. Syndr 11(Suppl 2), S643-s650 (2017).

Téoule, P. et al. Obesity and pancreatic cancer: A matched-pair survival analysis. J. Clin. Med. 9, 3526 (2020).

Lee, S. H., Tao, S. & Kim, H. S. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its related risk complications among Koreans. Nutrients 11, 1755 (2019).

Savadatti, S. S. et al. Metabolic syndrome among Asian Indians in the United States. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 25, 45–52 (2019).

Xia, B. et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of pancreatic cancer: A population-based prospective cohort study. Int. J. Cancer 147, 3384–3393 (2020).

Karim, S. A. M., Abdulla, K. S., Abdulkarim, Q. H. & Rahim, F. H. The outcomes and complications of pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure): Cross sectional study. Int. J. Surg 52, 383–387 (2018).

Liu, J. & Colditz, G. A. Relative efficiency of unequal versus equal cluster sizes in cluster randomized trials using generalized estimating equation models. Biom. J. 60, 616–638 (2018).

Turan, A. et al. Preoperative vitamin D concentration and cardiac, renal, and infectious morbidity after noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 132, 121–130 (2020).

Bhayani, N. H. et al. Effect of metabolic syndrome on perioperative outcomes after liver surgery: A National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) analysis. Surgery 152, 218–226 (2012).

Yu, M., Ryu, D. R., Kim, S. J., Choi, K. B. & Kang, D. H. Clinical implication of metabolic syndrome on chronic kidney disease depends on gender and menopausal status: Results from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 25, 469–477 (2010).

Glance, L. G. et al. Perioperative outcomes among patients with the modified metabolic syndrome who are undergoing noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 113, 859–872 (2010).

Myles, P. S. et al. Restrictive versus liberal fluid therapy for major abdominal surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 2263–2274 (2018).

Li, Y., Zhao, L., Yu, D., Wang, Z. & Ding, G. Metabolic syndrome prevalence and its risk factors among adults in China: A nationally representative cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 13, e0199293 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by 234 Clinical Climb Project of Changhai hospital affliated to Naval Medical University [grant number: 2019YXK022].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.D. and Y.S. contributed to drafting of the manuscript and statistical analysis. H.W. contributed to data curation. T.C. and B.X. contributed to data collection. Y.D. and T.X. contributed to study design, operation of the study and drafting of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dai, Y., Shi, Y., Wang, H. et al. Metabolic syndrome for the prognosis of postoperative complications after open pancreatic surgery in Chinese adult: a propensity score matching study. Sci Rep 13, 3889 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31112-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31112-x

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.