Abstract

Reflecting the first wave COVID-19 pandemic in Central Europe (i.e. March 16th–April 15th, 2020) the neurosurgical community witnessed a general diminution in the incidence of emergency neurosurgical cases, which was impelled by a reduced number of traumatic brain injuries (TBI), spine conditions, and chronic subdural hematomas (CSDH). This appeared to be associated with restrictions imposed on mobility within countries but also to possible delayed patient introduction and interdisciplinary medical counseling. In response to one year of COVID-19 experience, also mapping the third wave of COVID-19 in 2021 (i.e. March 16 to April 15, 2021), we aimed to reevaluate the current prevalence and outcomes for emergency non-elective neurosurgical cases in COVID-19-negative patients across Austria and the Czech Republic. The primary analysis was focused on incidence and 30-day mortality in emergency neurosurgical cases compared to four preceding years (2017–2020). A total of 5077 neurosurgical emergency cases were reviewed. The year 2021 compared to the years 2017–2019 was not significantly related to any increased odds of 30 day mortality in Austria or in the Czech Republic. Recently, there was a significant propensity toward increased incidence rates of emergency non-elective neurosurgical cases during the third COVID-19 pandemic wave in Austria, driven by their lower incidence during the first COVID-19 wave in 2020. Selected neurosurgical conditions commonly associated with traumatic etiologies including TBI, and CSDH roughly reverted to similar incidence rates from the previous non-COVID-19 years. Further resisting the major deleterious effects of the continuing COVID-19 pandemic, it is edifying to notice that the neurosurgical community´s demeanor to the recent third pandemic culmination keeps the very high standards of non-elective neurosurgical care alongside with low periprocedural morbidity. This also reflects the current state of health care quality in the Czech Republic and Austria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fully unexpected, in March 2020 the pandemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), known as COVID-19, struck at the heart of human life and has unpredictably changed the world, staying detrimental to all spheres of our daily living. Taking tentative primal epidemiological measures, postponement of elective surgeries was one of many not surprising consecutive yet still rectifiable aftermaths of the global pandemic. However, thenceforwards, alarming data on depleted emergency operations have been announced in various surgical branches1,2,3,4. Reflecting the peak pandemic of the first wave in the Czech Republic, Austria and Switzerland (i.e. March 16th—April 15th, 2020) the neurosurgical community witnessed a general diminution in the incidence of emergency neurosurgical cases1. This was impelled by a reduced number of traumatic brain injuries, spine conditions, and chronic subdural hematomas. Short-term mortality did not significantly differ overall or for any of the conditions investigated during the first wave of the pandemic. Lower incidence of neurosurgical emergency cases appeared to be associated with restrictions imposed on mobility within countries but also to possible delayed patient introduction and interdisciplinary medical counseling1.

More than one year after the global pandemic inception (and its worldwide announcement on 11th March 2020), keeping acquainted with the current COVID-19 forms, Central European health care systems have been continuously adjusting their approaches to the present pandemic situation, trying to maximize the quality of care whilst maintaining appropriate epidemiological measures. Meanwhile, in Central Europe the COVID-19 pandemic reached the third peak within the same period as the first wave (i.e. March 16th-April 15th, 2021).

In response to the third wave, we aimed to reevaluate the prevalence and outcomes for neurosurgical emergency cases in COVID-19-negative patients during the matching time period to the first wave (i.e. March 16th—April 15th, 2021) in Austria and the Czech Republic. The primary analysis addressed incidence and 30 day mortality in non-elective neurosurgical cases compared to four preceding years.

Methods

Mirroring a population of over twenty million people, our analysis comprised data from all neurosurgical centers in Austria and the Czech Republic. In the course of initial outbreak, these countries adjourned scheduled surgeries, and intensive care resources were preserved or redistributed. There was a high endeavor to proceed with non-elective surgeries without any restraints; yet, lacking the official guidelines, it was ambiguous which procedures required instantaneous resolution and what time frames were justifiable to initiate intervention. In defiance of the high prevalence of COVID-19 cases in Austria and the Czech Republic, there was no apparent deficiency in intensive care capacities within the pandemic culminations. Strikingly, the workflow was affected heavily in the first phase of the pandemic with all related uncertainties.

In 2021, similar actions were needed as COVID-19 cases reached a critical threshold. Hence, data on all emergency, cranial and spinal neurosurgical procedures performed during March 16th – April 15th, 2021, as well as 2020 were recorded. This time period was elected to mirror the peaks of the pandemic in these fields over both years. Noteworthy, analogous regulations were applied in both appraised countries over the defined time period. Cases from coincident time periods in the preceding three years (2017 – 2019) were analyzed for reference. Ethical approval was attained by the coordinating national centers (Ethikkommission Nummer der Medizischen Universität Innsbruck 1194/2021 in Austria and Etická komise FN Ostrava 448/2021 in the Czech Republic). All research was performed in conformity with the local guidelines as well as in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was waived by the approving ethic committees.

Patients

Demographic parameters such as age, sex and 30 day mortality as well as surgical data were retrospectively recorded in all participating centers. Patients who were treated conservatively, were not enrolled in the study. All inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1. Cases were categorized as follows: 1) traumatic brain injury (TBI) requiring any emergent neurosurgical intervention (i.e. monitoring for intracranial pressure, decompressive craniectomy, etc.), 2) chronic subdural hematomas (cSDH) requiring surgical evacuation due to the mass effect and/or neurological symptoms, 3) aneurysmal or non-aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, and other neurovascular pathologies, including cavernous malformations, arteriovenous fistulae, and arteriovenous malformations necessitating rapid treatment (i.e. latest within 2 weeks after onset), 4) spinal conditions necessitating emergency surgical treatment involving degenerative spine disease with new onset or acute deterioration of neurological symptoms (e.g., cauda equina syndrome and/or motor deficits, or signs of spinal cord compression), spine tumors including metastases, extradural, intradural and intramedullary tumors, infectious spine diseases, as well as traumatic spine injuries with or without neurological deficits, 5) acute deterioration of preexisting hydrocephalus (e.g., shunt dysfunction) or new onset hydrocephalus, and 6) newly diagnosed intracranial pathologies including high- or low-grade gliomas, meningiomas, ischemic or hemorrhagic strokes and intracranial hematomas requiring decompressive craniectomy or emergency surgery, and brain abscesses in need for rapid or emergency surgical scheduling (i.e. latest within 3 weeks after symptom onset or diagnosis).

Statistics

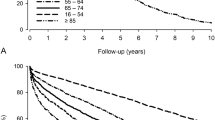

The number of total incident cases, and number within each category, were determined in each year, separately for Austria and the Czech Republic. Chi-square tests were applied to test for differences in incidence across the years, and significant differences (P < 0.05) were further examined using standardized residuals. Rates of 30-day mortality were determined for each year, and within each category separately for Austria and the Czech Republic. Thirty-day mortality was analyzed using logistic regression with year (2021/2020 versus 2017—2019) as an independent variable. All models were adjusted for age (0–18, 18–39, 40–64, 65–74, and 75 + years old) and sex.

Results

The participating centers in the Czech Republic and Austria recorded 2,242 and 2,835 emergency neurosurgical cases, respectively. Female patients represented 41% of the population in the Czech Republic and 45% in Austria. The median age in both countries was 61 years (ranging between 0 and 97 years in the Czech Republic, and between 0 and 95 years in Austria). One Austrian center could not provide any data but on spine cases for 2019 and 2020, and thus was excluded from descriptions and analyses of total cases and spine cases but was included for the other categories.

Incidence

Analyses revealed significant differences in incidence rates for cSDH, spine, acute hydrocephalus, and tumor cases in Austria, driven by their lower incidence rates in 2020. Overall incidence of neurosurgical cases demonstrated a significant peak in Austria in 2021. There was no significant difference in the total number of cases in the Czech Republic from 2017–2021. As previously reported, the TBI cases in the Czech Republic were high in 2019, while cSDH cases experience a high in 2018, and a low in 2020, causing significant differences in incidence rates over time. The only novel finding for the Czech Republic was a significant increase in spinal cases in 2021 (Table 2).

Demographics

Traumatic brain injury

There were no differences in patients´ age, TBI grade or initial GCS between the years in both Austria and the Czech Republic. The details are listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Chronic subdural hematoma

There were no differences in patients´ age or initial GCS between the years in both Austria and the Czech Republic. The results are listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage and other neurovascular lesions

There were no differences in patients´ age, SAH Hunt & Hess classification grades or Fisher score grades between the years in both Austria and the Czech Republic. Timing of treatment did not differ across the years in both countries. The results are listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Spine lesions

There were no differences in patients´ age between the years in both Austria and the Czech Republic. Timing from related symptoms to surgery did not differ across the years in both countries. The results are listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Acute hydrocephalus

Mean age of patients varied between the years in both Austria and the Czech Republic. New onset of acute hydrocephalus ranged between 44.4% and 66.7% in Austria and from 54.7% to 68.9% in the Czech Republic, with the highest rates occurring either in 2020 or in 2021. The results are listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Tumors and other intracranial lesions

There were no differences in patients´ age between the years in both Austria and the Czech Republic. Related symptoms ranged between 67.3 and 70.9% of patients across the years in Austria and from 66.9 to 73.7% of patients in the Czech Republic. The results are listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Thirty day mortality

Of the collected cases in the Czech Republic and Austria, 2314 (> 99.9% of total) in the Czech Republic, and 2220 (99.0%) in Austria, were included in the logistic regression analysis of short-term mortality. Logistic regression models imparted that the year 2021, compared to the years 2017–2019, did not significantly correlate with any increased odds of 30-day mortality in Austria or in the Czech Republic (Tables 5 and 6).

Neurological outcome at discharge

Traumatic brain injury

There were no differences in GOSE score across the years in both Austria and the Czech Republic with a mean grade ranging between 3 and 4 in both countries. The results are listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Chronic subdural hematoma

GOSE score did not differ across the years in both Austria and the Czech Republic, with a mean grade of 7 or 8 in Austria and an annual mean grade of 7 in the Czech Republic. The results are listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage and other neurovascular lesions

Both mean mRS and GOSE scores varied across the years in Austria ranging between 1 and 3, and from 1 to 7, respectively. In the Czech Republic, there were no differences in mRS score, with an annual mean grade of 2 except for 2020 where the mean grade was 3. GOSE score ranged between the mean grades 4 and 6 across the years. The results are listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Spine lesions

There were no differences in GOSE score across the years in both Austria and the Czech Republic, with an annual mean grade of 7 in Austria and a mean grade ranging from 6 to 7 in the Czech Republic. The results are listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Acute hydrocephalus

GOSE score varied across the years in Austria, with a mean grade ranging from 4 to 7, and the lowest grade in 2021. There were no differences in GOSE score across the years in the Czech Republic, with a mean grade of 5 or 6. The results are listed in Tables 1 and 2.

Tumors and other intracranial lesions

There were no differences in GOSE score across the years in both Austria and the Czech Republic, with an annual mean grade of 6 in both countries, except for 2019 in the Czech Republic where the mean grade was 5. The results are listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Discussion

Our current study reflecting the present status of health care services in the Czech Republic and in Austria imparted an overall significant propensity toward increased incidence rates of non-elective, emergency neurosurgical cases during the recent third COVID-19 pandemic wave in Austria, driven by their lower incidence during the first COVID-19 culmination in 2020. This actuality is confirmed partly also in the Czech Republic, markedly in spine cases. Selected neurosurgical conditions commonly associated with traumatic etiologies including TBI, and chronic subdural hematomas roughly reverted to similar incidence rates from the previous non-COVID-19 years. In defiance of long-suffering health care services and intensive care, the prior lower prevalence of spine cases and acute hydrocephalus in Austria also normalized. Again, albeit varying across the study period (2017–2021), 30-day mortality during the continuing COVID-19 pandemic in Austria and the Czech Republic was not substantially altered overall or for any condition compared to previous years. Mirroring the current state of health care quality in both Central European countries, our data anew indicate that emergency neurosurgical care continues to be provided at high standard level regardless of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has initiated unparalleled barriers to the delivery of health care all around the world5,6. In general, surgical practices have been substantially afflicted by the persisting COVID-19 pandemic. Above all, the most inauspicious impact experienced the preventive health care, with innumerable (infinite) postponed elective surgeries in every surgical field5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Urgently reacting to the first pandemic culmination, several national guidelines devoted to elective case scheduling during a pandemic were announced by national authorities, for instance, the American College of Surgeons (ACS)12 and the CMS12,13. Some protocols accentuated social distancing as an imperative measure to curtail viral spread14,15. Thereafter, a series of federal propositions and administrative regulations from 31 states asserted all intended surgical interventions and elective inpatient diagnostic examinations to be postponed16,17,18,19. However, the dichotomization of elective versus non-elective interventions was condemned for incompetently risk-stratifying patients20. The potential adverse effects consequent upon a delay in a scheduled intervention differ by neurosurgical specialty, whether neurooncology, vascular, functional, pediatrics, or spine21.

The collective Congress of Neurological Surgery and American Association of Neurological Surgeons (CNS/AANS) Tumor Sect. 22 declared their own protocol given the unique nature of neurooncological diseases. They urged surgical interventions for all newly diagnosed cranial or spinal metastatic diseases, and high-grade gliomas. They were exponents of narrow follow-ups for benign asymptomatic pathologies and low-grade gliomas. The CMS13 propounded a three-level algorithm wherein low-acuity services were rescheduled or effected via telemedicine, intermediate-acuity services were triaged, and high-acuity were pursued without any significant delay. Similarly, the European Association of Neurological Societies (EANS)23 advised triages of neurosurgical interventions based on a categorization of emergency conditions. This tool was based on the Elective Surgery Acuity Scale (ESAS)24 from St. Louis University. While the tool gives examples of neurosurgical procedures in each category, the EANS exhorted the national neurosurgical societies to create more granular triage schemes based on regional capacity.

Dealing with non-elective emergency cases, for instance, the German Association of Neurological Surgeons (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurochirurgie – DGNC)25 introduced general guidelines stating that risks of death as well as of the permanent morbidity owing to surgery postponement in these patients must be weighed against the risks of COVID-19 disease. Including all relevant neurosurgical fields, neurosurgical patients who might be threatened by deferral of indicated neurosurgical treatment are to be treated as an emergency irrespective of current COVID-19 restrictions. Our present data are in harmony with these recommendations. Standing the rough continuing COVID-19 pandemic situation, the Austrian and Czech neurosurgical community have been succeeding in keeping high standards of emergency neurosurgical health services, without any pertinent threats for our patient population. Regrettably, this is not a matter of course in all other health care spheres26. Ultimately, one should also keep in mind that there might be more indirect erratic repercussions in the future concerning not only neurosurgical patients, for example the resulting lack of neurosurgical training for our residents. All these possible implications will require appropriate handling of the topical situation.

Health care services worldwide continue to improvise, ceaselessly revising and optimizing the current local protocols to maintain possibly the most effective level of performance amidst substantial scarcity in equipment and facilities. Being in a lucky position in social welfare Central Europe, quality of care remains at the high level, not yet directly troubled with handling COVID-19 complications.

It is worth of noting that, for instance, in Austria during the very first pandemic culmination the occupancy of ICU beds reserved for COVID patients ranged between 5 and 18%. In the current study period, the ICU beds occupancy substantially increased, ranging from 55 to 68% by the same number of 682 reserved ICU beds (https://covid19.healthdata.org/austria?view=resource-use&tab=trend&resource=all_resources). The similar trend occurred also in the Czech Republic (https://onemocneni-aktualne.mzcr.cz/vyvoj-kapacit-luzkove-pece). Specifically, in April 2020, there were on average 55 ventilated patients with COVID-19 whereas one year later (April 2021) there were 531 such patients (https://onemocneni-aktualne.mzcr.cz/api/v2/covid-19). Taking heed of constitutive COVID-19 measures during the first and third pandemic waves, most principal restrictions such as general shutdown, isolation of COVID patients etc. remained similar during both time periods, as in the hospitals so for the public. Importantly, given the one-year intense experience and the resultant acquired skills with treatment of COVID-19 patients, all related procedures became routine in daily clinical practice regardless of substantially increased number of intensive care patients. Also, access to all necessary consumables improved with time.

Importantly, in defiance of this evident growing need of ICU beds, we did not observe any germane effect on the provided neurosurgical care in both countries. By contrast, there was an overall significant propensity toward increased incidence rates of non-elective, emergency neurosurgical cases during the recent third COVID-19 pandemic wave in 2021. Up to now, strictly following our neurosurgical knowledge and contemporary standard operating procedures in both countries, our data revealed no worsening in any of patient outcomes in all examined fields. Unlike, Patel et al.21 observed trends of deterioration in neurological findings, malignant dissemination, abscesses in non-traumatic spine cases, and the progress of structural instability in the first wave of the pandemic.

As both countries Austria and the Czech Republic keep adapting to the COVID-19 situation, a better cognizance of the inordinate repercussions on definite subspecialties can acquaint targeted care reescalation in all health care programs and future research appraising the ramifications of pandemic on long-term outcome. Within neurosurgical practice, a detailed analysis of all pertinent effects of the COVID-19 pandemic alongside with the current measures is instrumental in refining the necessary requirements and protocols. Sharing the same opinion21, for future contagions or akin health catastrophes, validated predictive models shall notify an outcome-based framework to better delineate scheduled surgery and the straight surgical care of patients, allocating all necessary surgical resources.

Leading strengths of our study were the large sample size alongside with inclusion of multiple reference periods (2017–2019) for comparison to the first COVID-19 culmination in 2020 and the recent pandemic wave in the same time period in 2021 (i.e. March 16th–April 15th) and representation of all neurosurgical centers in Austria and the Czech Republic. Yet, the interpretation of our data is bounded by the retrospective and observational nature of the study. Also, only patients who were treated surgically in an emergency fashion, were analyzed. Hence, surgical prioritization during the proceedings of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as thenceforth persists fundamental27. Ultimately, one shall be aware that COVID-19 pandemic exerts deleterious influence upon diverse diseases, leading also to consequential neurological manifestations28,29 and some patients may require neurosurgical care.

Conclusion

Further resisting the major deleterious effects of the continuing global COVID-19 pandemic, it is, again, edifying to notice that the neurosurgical community´s demeanor to the recent another pandemic culmination in at least Central Europe keeps the very high standards of non-elective neurosurgical care alongside with low periprocedural morbidity. This also reflects the current state of health care quality in both countries Austria and the Czech Republic. Yet, one may not rest on their own laurels.

References

Grassner, L. et al. Trends and outcomes for non-elective neurosurgical procedures in Central Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Rep. 11, 6171. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-85526-6 (2021).

Ahuja, S., Shah, P. & Mohammed, R. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on acute spine surgery referrals to UK tertiary spinal unit: Any lessons to be learnt?. Br. J. Neurosurg. 35, 181–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/02688697.2020.1777263 (2021).

Cano-Valderrama, O. et al. Acute care surgery during the COVID-19 PANDEMIC IN Spain: Changes in volume, causes and complications. A multicentre retrospective cohort study. Int.J. Surg. (Lond. Engl.) 80, 157–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.07.002 (2020).

Wade, S., Nair, G., Ayeni, H. A. & Pawa, A. A cohort study of emergency surgery caseload and regional anesthesia provision at a tertiary UK hospital during the initial COVID-19 pandemic. Cureus 12, e8781. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.8781 (2020).

Diaz, A., Sarac, B. A., Schoenbrunner, A. R., Janis, J. E. & Pawlik, T. M. Elective surgery in the time of COVID-19. Am. J. Surg. 219, 900–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.04.014 (2020).

Søreide, K. et al. Immediate and long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on delivery of surgical services. Br. J. Surg. 107, 1250–1261. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11670 (2020).

Gilbert, M., Dewatripont, M., Muraille, E., Platteau, J. P. & Goldman, M. Preparing for a responsible lockdown exit strategy. Nat. Med. 26, 643–644. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0871-y (2020).

Willan, J. et al. Assessing the impact of lockdown: Fresh challenges for the care of haematology patients in the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Haematol. 189, e224–e227. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.16782 (2020).

Mukhtar, S. Preparedness and proactive infection control measures of Pakistan during COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. Res. Soc. Administrative Pharm. RSAP 17, 2052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.011 (2021).

Stensland, K. D. et al. Considerations in the triage of urologic surgeries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Urol. 77, 663–666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.027 (2020).

Spinelli, A. & Pellino, G. COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives on an unfolding crisis. Br. J. Surg. 107, 785–787. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11627 (2020).

American College of Surgeons. COVID-19: recommendations for management of elective surgical procedures. Available at: https://www.facs.org/covid19/clinical-guidance/elective-surgery. (2020).

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Nonemergent, elective medical services, and treatment recommendations. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/cms-non-emergent-electivemedical-recommendations.pdf.

Wilder-Smith, A. & Freedman, D. O. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: Pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. J. Travel Med. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taaa020 (2020).

Frieden, T. R. & Lee, C. T. Identifying and interrupting superspreading events-implications for control of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 26, 1059–1066. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2606.200495 (2020).

American College of Surgeons. COVID-19: executive orders by state on dental, medical, and surgical procedures. Available at: https://www.facs.org/covid-19/legislative-regulatory/executiveorders. (2020).

Lee B. Executive Order 18: An order to reduce the spread of COVID-19 by Limiting Nonemergency Health Care Procedures. Available at: https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/pub/execorders/execorders-lee18.pdf. (2020).

Lee B. Executive Order 25: An order to reduce the spread of COVID-19 by limiting nonemergency healthcare procedures. Available at: https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/pub/execorders/execorders-lee25.pdf (2020).

Centers for disease control and prevention. Interim Guidance for Healthcare Facilities: Preparing for community transmission of COVID-19 in the United States. Available at: https://asprtracie.hhs.gov/technical-resources/resource/8232/interim-guidancefor-healthcare-facilities-preparing-for-communitytransmission-of-covid-19-in-the-united-states (2020).

Stahel, P. F. How to risk-stratify elective surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic?. Patient Saf. Surg. 14, 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13037-020-00235-9 (2020).

Patel, P. D. et al. Tracking the volume of neurosurgical care during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. World Neurosurg. 142, e183–e194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.06.176 (2020).

Ramakrishna, R., Zadeh, G., Sheehan, J. P. & Aghi, M. K. Inpatient and outpatient case prioritization for patients with neuro-oncologic disease amid the COVID-19 pandemic: General guidance for neuro-oncology practitioners from the AANS/CNS tumor section and society for neuro-oncology. J. Neurooncol. 147, 525–529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-020-03488-7 (2020).

European Association of Neurosurgical Societies (EANS). Triaging non-emergent neurosurgical procedures during the COVID-19 outbreak Available at: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.eans.org/resource/resmgr/documents/corona/eans_advice2020_corona.pdf (2020).

Smeds, M. R. & Siddiqui, S. Proposed resumption of surgery algorithm after the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. J. Vasc. Surg. 72, 393–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2020.05.024 (2020).

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurochirurgie (DGNC). Nicht-elektive Eingriffe des Neurochirurgischen Fachgebiets. Available at: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.eans.org/resource/resmgr/documents/corona/dgnc_bdnc_op-indikationen_ge.pdf (2020).

Ali, S., Khan, M. A., Rehman, I. U. & Uzair, M. Impact of covid 19 pandemic on presentation, treatment and outcome of paediatric surgical emergencies. J. Ayub Med. College Abbottabad JAMC 32(Suppl 1), S621-s624 (2020).

Brindle, M. E., Doherty, G., Lillemoe, K. & Gawande, A. Approaching surgical triage during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Surg. 272, e40–e42. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000003992 (2020).

Zubair, A. S. et al. Neuropathogenesis and neurologic manifestations of the coronaviruses in the age of coronavirus disease 2019: A review. JAMA Neurol. 77, 1018–1027. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2065 (2020).

Pleasure, S. J., Green, A. J. & Josephson, S. A. The spectrum of neurologic disease in the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 pandemic infection: Neurologists move to the frontlines. JAMA Neurol. 77, 679–680. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1065 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Many sincere thanks to all Czech and Austrian neurosurgical centers that consented to participate and to Dr. Lucie Petrova for reviewing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.P.: conceptualization/design of the study, methodology, supervision/study coordination (A/CZ), investigation/data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, writing – original draft preparation L.G.: conceptualization/design of the study, methodology, data analysis and interpretation, writing – review & editing the manuscript FMW: formal analysis of data, data interpretation, writing – review & editing the manuscript M.D.: study coordination (CZ), investigation/data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, literature search RV: study coordination (CZ), investigation/data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, literature search PG, KB, SG, LCM, R.B., S.F., M.M., A.R., T.K., T.R., F.R.N., H.S., A.G., M.S., C.S., C.G., F.M., C.S., J.P.W., K.R., J.J.Z., M.O., W.P., M.M., F.A.T.B., J.B., L.K., R.L., M.K., J.F., P.K., V.P., M.T., V.B., P.K., T.C., R.K., A.C., P.H., D.P., D.K., A.S., M.S., J.D., A.J., P.B., R.T., J.K., V.J., M.S., P.L., M.K., D.H., R.J.: investigation/acquisition of data J.L.K.K.: formal analysis of data and interpretation, writing – review & editing the manuscript C.T.: conceptualization/design of the study, supervision/study coordination (A), data interpretation, writing – review & editing the manuscript D.N.: conceptualization/design of the study, supervision/study coordination (CZ), data interpretation, writing – review & editing the manuscript All authors have approved the submitted version and have agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, have been appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature. Acknowledgments: Many sincere thanks to all Czech and Austrian neurosurgical centers that consented to participate and to Dr. Lucie Petrova for reviewing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Petr, O., Grassner, L., Warner, F.M. et al. Current trends and outcomes of non-elective neurosurgical care in Central Europe during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Rep 12, 14631 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18426-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18426-y

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.