Abstract

Neonatal hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy is a notable cause of neonatal death and developmental disabilities. To achieve better outcomes, it is important in treatment strategy selection to categorize the degree of hypoxia ischemia and evaluate dose response. In an asphyxia piglet model with histopathological brain injuries that we previously developed, animals survived 5 days after insult and showed changes in cerebral blood volume (CBV) that reflected the severity of injuries. However, little is known about the relationship between changes in CBV during and after insult. In this study, an HI event was induced by varying the amount and timing of inspired oxygen in 20 anesthetized piglets. CBV was measured using near-infrared time-resolved spectroscopy before, during, and 6 h after insult. Change in CBV was calculated as the difference between the peak CBV value during insult and the value at the end of insult. The decrease in CBV during insult was found to correlate with the increase in CBV within 6 h after insult. Heart rate exhibited a similar tendency to CBV, but blood pressure did not. Because the decrement in CBV was larger in severe HI, the CBV increment immediately after insult is considered useful for assessing degree of HI insult.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neonatal hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) is a notable cause of neonatal death and developmental disabilities1. In meta-analyses, nearly 50% of neonates treated with therapeutic hypothermia (TH) still have major disabilities or die due to multi-organ injuries2. To achieve better outcomes, categorizing the degree of the hypoxia–ischemia (HI) is important for selecting suitable candidates for TH and any additional treatment strategies3,4,5. Many studies suggest that TH provides maximum neuroprotection when initiated within 6 h of birth. Therefore, it is important to recognize the changes in cerebral hemodynamics in neonates with HIE as early as possible after HI insult.

Understanding changes in cerebral hemodynamics and cerebral oxygenation status in neonatal HIE is beneficial for the prognosis of HIE, the monitoring of ongoing therapy, and the evaluation of novel therapies. In recent years, the use of near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) for monitoring oxygenation of the brain has provided useful insights for the management of newborns who require respiratory support, cardiovascular support, or transfusion, have HIE, or have undergone surgery6,7.

In neonatal HIE, HI insult affects cerebral hemodynamics and oxygenation status due to impairment in cerebral autoregulation. Impaired cerebral autoregulation results in adverse neurological outcomes8,9. Because assessment of vital parameters such as heart rate (HR), mean arterial blood pressure (MABP), and systemic oxygen saturation (SaO2) may not always reflect the extent of brain injury10,11, for a complete clinical picture, assessment of neonatal cerebral oxygenation and perfusion should be performed.

We previously developed a novel asphyxia piglet model with a uniform degree of histopathological brain injuries, where animals survived 5 days after insult and showed changes in cerebral blood volume (CBV), detected using near-infrared time-resolved spectroscopy (TRS)12. In all piglets that received HI insult, CBV increased to the peak value before decreasing to a minimum value at the time of resuscitation. These changes in CBV during insult suggested that CBV increased in a compensatory fashion under HI and that cerebral blood flow autoregulation then became impaired, resulting in decreased CBV. In further work, we observed that the decrease in CBV during insult reflected the severity of brain injuries sustained from impaired cerebral autoregulation12,13. Hence, we suggested that the degree of HI insult can be estimated by measuring CBV with TRS. Furthermore, when examining CBV changes not only during insult but also after insult in piglets, we found that the increase seen in CBV within 6 h after insult reflected the severity of the histological brain injuries seen at 5 days after the insult14. Based on these findings in piglets, we then found that the increment in CBV during the first 6 h after birth in human neonates is an indicator of poor neural prognosis thereafter15.

Even though it has been proved in the piglet that changes in CBV during and after HI insult reflect severity of the brain injuries sustained, little is known about the relationship between the changes in CBV during and after insult. To unravel this relationship, it would be helpful to estimate the cerebral hemodynamic response during HI insult by evaluating the cerebral hemodynamic patterns after it. We hypothesized that piglets with a greater decrease in CBV during HI insult would show a greater increase in CBV within the first 6 h after insult. The objective of this study was thus to evaluate the relationship between the CBV changes during HI insult and within 6 h of the insult in the asphyxiated piglet.

Results

Physiological parameters are shown in Table 1. Piglets in the control group showed no significant differences versus baseline values. All parameters were compared with their respective baseline values. In the HI group, pH and base excess decreased at the time of resuscitation and had returned to baseline at 60 min after insult. Blood glucose increased at the start of resuscitation and returned to baseline 360 min after insult, whereas lactate had not returned to baseline by 360 min. PaCO2 and PaO2 values at resuscitation were 31.2 (7.4) and 16.3 (5.1) mmHg, respectively. After resuscitation, both values were within the normal range. Compared with the control group, a significant difference was seen in pH, pO2, BE, blood glucose, lactate, and rectal temperature immediately before resuscitation in HI piglets and pH, BE, and lactate continued in the same manner until 60 min after insult.

The data for cerebral oxyhemoglobin (oxyHb) concentration, deoxyhemoglobin (deoxyHb) concentration, total hemoglobin (totalHb) concentration, CBV, cerebral Hb oxygen saturation (ScO2), MABP, and HR are shown in Table 2. During insult, CBV, totalHb, and deoxyHb increased to a maximum value and then declined, whereas oxyHb and ScO2 decreased and maintained lower values at the end of insult. CBV, oxyHb, and totalHb had increased again at 5 min after insult and had returned to baseline by 180 min, whereas deoxyHb decreased immediately after insult and then gradually increased. MABP decreased at the end of insult, had increased at 5 min, and had returned to baseline by 60 min after insult. HR fell during insult, gradually increased from the start of resuscitation, and had stabilized by 60 min after insult.

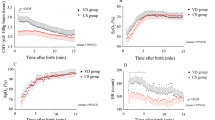

There was a positive correlation between changes in CBV during insult and changes in CBV at all time points after insult (5, 60, 180, and 360 min; Fig. 1). Similarly, the MABP increment during insult showed a positive correlation with that at 5 min after insult. However, the remaining time points showed no correlation with the MABP increment during insult (Fig. 2). The HR increment during insult and the HR increments at all time points after insult also showed a positive correlation (Fig. 3). TotalHb showed a positive correlation and ScO2 showed a negative correlation between changes at only 5 min and 60 min after insult, but oxyHb and deoxyHb did not show any correlations (Table 3).

Correlation between change in HR during insult and change in HR at (A) 5 min, (B) 60 min, (C) 180 min, and (D) 360 min after insult. HR changes were defined as the differences between the HR value at peak CBV during insult and the HR value immediately before resuscitation 5, 60, 180, and 360 min after insult.

Discussion

In this study, we have revealed the relationships between the decrease in CBV during HI insult and the increase in CBV within 6 h of the insult in HIE piglets. This CBV decrease during insult and increase within 6 h after insult was correlated. HR showed a similar tendency to CBV but MABP did not.

During HI insult, CBV increases rapidly in a compensatory fashion, followed by impaired cerebral blood flow autoregulation and vasoparalysis that result in gradually decreased CBV due to decompensation16,17. In our previous translational HI piglet studies, greater decreases in CBV from baseline during insult were associated with severe brain damage or death12.

With respect to the increase in CBV after HI insult, we have two theories to explain why greater decreases in CBV during insult were followed by greater increases in CBV after insult. The first is severe cerebral vasoparalysis due to impaired cerebral autoregulation. Cerebral hypoperfusion, and thus decreased CBV, which are induced by severe systemic hypotension, would impair cerebral vascular autoregulation during the HI insult. After the initial resuscitation, cerebral blood flow would become passive due to a rise in systemic BP and result in an increase in CBV in the acute period immediately after resuscitation. The second is cerebral venous congestion due to heart failure, although we failed to identify a relationship between the CBV increase and the severity of the cardiac dysfunction from the data obtained in the present study, such as HR and BP. Our previous studies showed that increases in CBV at 1, 3, and 6 h after insult were associated with depressed neurocortical electrical activity at the respective time points13 and also histopathological brain injury at 5 days after insult14.

Hence, this sequence of more pronounced cerebral hypoperfusion during insult being followed by greater cerebral hyperfusion after insult reflected impaired cerebral autoregulation and resulted in severe brain injuries. In clinical practice, HIE neonates are at risk of cerebral blood flow dysregulation. Several studies have shown that impaired cerebral autoregulation (pressure-passive cerebral blood flow) after birth was associated with poor neurological outcomes18 and increased mortality19. Therefore, our work additionally suggests that CBV monitoring with TRS within the first 6 h after birth can estimate the degree of hypoperfusion during labor in HIE neonates and, further, can categorize the severity of brain injuries by recognizing the patterns of sequential changes in CBV during and after insult.

The increment in HR during insult and the increments in HR at all time points after insult showed a positive correlation. Significant cardiovascular dysfunction with redistribution of blood flow occurs in HI. In the initial stages of HI, cardiac output (CO) is well compensated and the distribution of blood to organs is maintained. However, blood is gradually redistributed to vital organs such as the brain and heart20,21. Myocardial ischemia results in ventricular dysfunction, which leads to a fall in stroke volume. Despite this reduced stroke volume, CO remains unchanged due to increased HR in the compensation phase, and HR also falls in the decompensation phase. The increment in HR after insult is to deliver the necessary oxygen, and the amount of increment depends on the degree of HI insult. This result is similar to that of another study in which fetal sheep were subjected to complete umbilical cord occlusion. The severe insult group showed more tachycardia than the mild insult group, and this phenomenon was related to active suppression of autonomic activity of the brain stem22.

MABP changes during HI constitute a complex phenomenon. MABP is influenced by multiple factors, including CO, autonomic function, neuroendocrine response, degree of vasoparalysis, and peripheral resistance20,23. In HI neonates, autonomic dysfunction with attenuation of parasympathetic activity and increased sympathetic activity influence the hemodynamic changes24,25. During HI, due to the autonomic dysfunction, compensatory tachycardia and increased BP occur initially and are followed by decompensation with a fall in HR and BP. After resuscitation, although both HR and MABP increased, MABP had returned to the level before insult earlier than HR did, and this was the reason for the lack of association between MABP increment at any time points except 5 min after insult and that during insult. This phenomenon is similar to that observed by Ikeda et al.26, who investigated moderate histologic damage in fetal lambs with umbilical cord ischemia. It is also similar to the findings of Yamaguchi et al.22 who found that 25 min of complete umbilical cord occlusion led to MABP decreasing more rapidly than HR over 6 h. On the other hand, HR and MABP were not associated with ScO2 and tissue perfusion index after resuscitation, indicating the difficulties of predicting cerebral circulatory disturbance27.

A graphical summary of this study and our previous work with the HI piglet model is shown in Fig. 4. In our previous study, the piglets whose CBV value was lower at the end of HI insult than at baseline showed poor prognosis, with almost all dying after insult, but almost all the piglets whose CBV value at the end of insult was higher than at baseline survived12. Another of our studies showed that increments in CBV after HI insult were well correlated with histopathological scores, especially at 1 and 3 h after resuscitation14. The results of the present study show that a greater decrease in CBV during HI insult leads to a greater increase in CBV within the first 6 h after insult, which indicates that an increase in CBV after insult can provide information not only on the degree of insult, but also on subsequent prognosis. Using these results, we can categorize three patterns of changes in CBV during and within 6 h after HI insult. A schematic representation of the patterns of changes in CBV are shown according to severity of insult: (A) in mild HI insults, a slight CBV decrease during the insult and a decrease to baseline after the insult; (B) in moderately severe insults, a CBV decrease during the insult above the baseline and a decrease after the insult that is smaller than that of (A); and (C) in severe insults, a CBV decrease during the insult to below the initial basal level of CBV and an increase after the insult. The angles of the CBV changes from the basal horizontal line after insult are α < β < γ (angle values of α and β are negative, whereas that of γ is positive). The categorization of each group was related to the prognosis within 5 days after insult. In pattern (A), the piglets all survived 5 days after the insult with no obvious neural pathological damage. In pattern (B), the piglets survived, but they had neural pathological damage. In pattern (C), the piglets did not survive after the insult due to severe convulsions or cardiac and respiratory failure. Thus, we can categorize the animals into groups by using the changes in CBV measured by TRS within 6 h after the insult to estimate future prognosis. This categorization could be applied to neonates with asphyxia to predict prognosis and we will plan to investigate this in future work.

Schematic representation of the three types of changes in CBV during HI insult and after insult according to severity of insult. (A) In mild insults, CBV falls slightly during the insult and decreases to baseline after resuscitation. (B) In moderately severe insults, CBV decreases during the insult above the baseline and decreases after resuscitation to a smaller extent than in (A). (C) In severe insults, CBV falls during the insult to below the baseline and increases after resuscitation. The angles of the CBV changes from the basal horizontal line after resuscitation are α < β < γ (the angle values of α and β are negative, whereas that of γ is positive).

The limitations of this study are as follows. Extra cerebral layer (skull and scalp) signals that influence the NIRS signal are not negligible in cerebral measurements. Milej et al.28 reported TRS measurements could reduce the contribution of the scalp to brain hemodynamic signals by an interoptode distance of over 3 cm in human adults. Because human neonates have a thin skull, superficial layer contamination is weaker than in adults29. Kienle et al.30,31 investigated analytical solutions to a two-layered optical phantom model using phase-modulated spectroscopy and demonstrated that a superficial layer 4-mm thick (or less) will have only a small influence on the accuracy of the measured optical properties of an underlying thick layer. In the piglets used in the present study, the scalp and skull layers measured postmortem were about 1.5 and 1.5 mm thick, respectively32, which are similar to measurements obtained in other studies33,34. Huber et al.33 and Fantini et al.34 concluded that in the case of a relatively thin scalp and skull layer (less than 4 mm, such as in neonatal piglets), the absolute values of Hb concentration and oxygen saturation should be representative of the brain.

Carbon dioxide is one of the most potent regulators of cerebral blood flow. In this study, PaCO2 was 31 mmHg during the HI insult when the ventilator was not completely stopped. This low PaCO2 level is different from the condition of clinical HIE where hypercapnia is observed. However, the findings of our final histopathological evaluation were similar to those of HIE, and we also observed changes in the CBV characteristic of reperfusion after ischemia. Thus, the findings of this study can serve as a reference of changes in cerebral hemodynamics in clinical HIE. Also, PaO2 and PaCO2 were maintained within the normal range during the observation period after resuscitation. Hypocapnia after resuscitation is a poor prognostic factor for HIE35,36, and changes in CO2 concentration needs to be further investigated in the future.

In HIE, the important determinants of outcomes are not only the severity of HI during insult, but also the duration and frequency of the insult, sexual dimorphism, and the presence of infection/inflammation5,37,38. We could only assess HI severity in this study.

Conclusion

In this study, greater decreases in CBV during HI insult were associated with greater increases in CBV after insult. The increment in CBV immediately after resuscitation is useful for assessing the degree and timing of hypoxia, and for predicting the severity of HI insult. By using TRS, evaluating CBV changes within 6 h of HI insult has the potential to categorize the severity of the HI and enable timely and appropriate therapy to be initiated.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval and animal preparation

The study protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Kagawa University (15070-1) and in accordance with Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines. The study was carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Four HI piglets in our previous study were excluded from the present study due to insufficient data records14, and six new HI piglets were added for this new analysis. A total of 23 newborn piglets within 24 h of birth (14 males, 9 females; body weight 1560–2200 g) including 3 sham controls were anesthetized and surgically prepared.

Before the experimental procedures, the piglets were placed under a radiant warmer and their activities and alertness were briefly observed. Anesthesia was induced with 1%–2% isoflurane (Forane inhalant liquid; Abbott Co., Tokyo, Japan) in air using a facemask. Each piglet was then intubated and mechanically ventilated with an infant ventilator. The umbilical vein and artery were cannulated with a 3- or 4-Fr neonatal umbilical catheter (Atom Indwelling Feeding Tube for Infants; Atom Medical Co., Tokyo, Japan). The umbilical vein catheter was placed 5 cm from the incision for blood pressure (BP) monitoring, and the umbilical artery catheter was placed 15 cm from the incision for blood sampling. After cannulation, the piglets were anesthetized with fentanyl citrate at an initial dose of 10 µg/kg followed by continuous infusion at 5 µg/kg/h and were then paralyzed with pancuronium bromide at an initial dose of 100 µg/kg followed by continuous infusion at 100 µg/kg/h. Maintenance solution (electrolytes plus 2.7% glucose [KN3B]; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan) was infused continuously at a rate of 4 mL/kg/h via the umbilical vein (glucose was infused at a rate of 2 mg/kg/min). Arterial blood samples were taken at critical points and when clinically indicated throughout the experiment. Each piglet was then placed in a copper mesh-shielded cage under a radiant warmer to maintain a rectal temperature of 38.0 ± 0.5 °C. Inspired gas was prepared by mixing O2 and N2 gases to obtain the oxygen concentrations required for the experiment. Ventilation was adjusted to maintain PaO2 and PaCO2 within their normal ranges. Arterial BPs were measured and recorded via the umbilical arterial catheter.

Time-resolved near-infrared spectroscopy and analysis

A portable three-wavelength TRS system (TRS-10; Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., Hamamatsu, Japan) was applied using probes attached to the head of each piglet. The light emitter and detector optodes were positioned on the parietal region with a 30-mm interoptode distance. In the TRS system, a time-correlated single-photon counting technique is used for detection. The oxyHb and deoxyHb concentrations were calculated from the absorption coefficients of oxidized Hb and deoxidized Hb, under the assumption that background absorption was due only to 85% (by volume) water. TotalHb, ScO2, and CBV were calculated as described previously32,39.

Hypoxic–ischemic insult protocol

The protocol is described in detail in our previous studies3,12,13,14. Briefly, after anesthesia induction, the piglets were stabilized. The HI insult was induced by decreasing the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) to 4%. Low-amplitude aEEG (LAEEG < 5 μV) was achieved by additional reductions of FiO2 to no less than 2%. FiO2 was adjusted during the insult to maintain LAEEG at < 5 μV, heart rate (HR) at > 130 beats/min, and mean arterial BP (MABP) at > 70% of baseline. The insult was terminated by resuscitation with 100% FiO2 for 10 min. Control animals (n = 3) received 21% FiO2 for the duration of the experiment. CBV, vital parameters, and aEEG were measured continuously for 360 min after insult.

Data analysis

The MABP, HR, and CBV values were analyzed from before insult to 360 min (6 h) after it. CBV changes during insult were defined as follows: Changes in CBV during insult = (maximum CBV value during insult) − (CBV value at the start of resuscitation).

CBV was measured continuously for 6 h after resuscitation. Changes in CBV values at 5, 60, 180, and 360 min after insult were calculated as follows: Changes in CBV at each time point = (CBV values at each time point) − (CBV value at the start of resuscitation).

In addition, the following relationships were analyzed (Fig. 5): (1) relationship between changes in CBV during insult and changes in CBV at each time point after insult; (2) relationship between the MABP increment at maximum CBV during insult and MABP increment at each time point after insult; and (3) relationship between the HR increment at maximum CBV during insult and HR increment at each time point after insult.

Graphical representation of the increments in CBV, HR, and MABP during HI insult and at 5, 60, 180, and 360 min after insult. Increments in CBV were calculated as the differences between the CBV value at the end of insult and the maximum CBV value during insult and the CBV at 5 min, 60 min, 180 min, and 360 min after insult. Increments in HR were calculated as the differences between the HR value at the end of insult and the HR value at the maximum CBV during insult and the HR at 5 min, 60 min, 180 min, and 360 min after insult. Increments in MABP were calculated as the differences between the MABP value at the end of insult and the MABP value at the maximum CBV during insult and the MABP at 5 min, 60 min, 180 min, and 360 min after insult.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 5J (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) was used for all statistical analyses. Significant correlations were assessed by Spearman’s p rank test for the relationship between changes in CBV, HR, and MABP during and after insult. Physiological variables of the HI group were compared with those of the control group using the Mann–Whitney U test and, in each group, these variables were compared with those of pre-baseline data using Dunnett's multiple comparison test. Statistical significance for all tests was set at p < 0.05. All values are presented as means ± SD.

References

Volpe, J. J. Neurology of the Newborn. 6th ed., 510–563 (Elsevier, 2008).

Jacobs, S. E., et al. Cooling for newborns with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003311.pub3 (2013).

Htun, Y. et al. Hydrogen ventilation combined with mild hypothermia improves short-term neurological outcomes in a 5-day neonatal hypoxia–ischaemia piglet model. Sci. Rep. 9, 4088 (2019).

Bonifacio, S. L., deVries, L. S. & Groenendaal, F. Impact of hypothermia on predictors of poor outcome: how do we decide to redirect care?. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 20, 122–127 (2015).

Gunn, A. J. & Bennet, L. Fetal hypoxia insults and patterns of brain injury: insights from animal models. Clin. Perinatol. 36, 579–593 (2009).

Dix, L. M., van Bel, F. & Lemmers, P. M. Monitoring cerebral oxygenation in neonates: an update. Front. Pediatr. 5, 46 (2017).

Kusaka, T. et al. Evaluation of cerebral circulation and oxygen metabolism in infants using near-infrared light. Brain Dev. 36, 277–283 (2014).

Ferriero, D. M. Neonatal brain injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 1985–1995 (2004).

Alderliesten, T. et al. Cerebral oxygenation, extraction, and autoregulation in very preterm infants who develop peri-intraventricular hemorrhage. J. Pediatr. 162, 698–704 (2013) (e2).

Lemmers, P. M., Toet, M. C. & van Bel, F. Impact of patent ductus arteriosus and subsequent therapy with indomethacin on cerebral oxygenation in preterm infants. Pediatrics 121, 142–147 (2008).

Lemmers, P. M. et al. Patent ductus arteriosus and brain volume. Pediatrics 137, e20153090 (2016).

Nakamura, S. et al. Cerebral blood volume combined with amplitude-integrated EEG can be a suitable guide to control hypoxic/ischemic insult in a piglet model. Brain Dev. 35, 614–625 (2013).

Nakamura, S. et al. Relationship between early changes in cerebral blood volume and electrocortical activity after hypoxic–ischemic insult in newborn piglets. Brain Dev. 36, 563–571 (2014).

Nakamura, M. et al. Cerebral blood volume measurement using near-infrared time-resolved spectroscopy and histopathological evaluation after hypoxic–ischemic insult in newborn piglets. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 42, 1–9 (2015).

Nakamura, S. et al. Simultaneous measurement of cerebral hemoglobin oxygen saturation and blood volume in asphyxiated neonates by near-infrared time-resolved spectroscopy. Brain Dev. 37, 925–932 (2015).

Shadid, M., Hiltermann, L., Monteiro, L., Fontijn, J. & Van Bel, F. Near infrared spectroscopy-measured changes in cerebral blood volume and cytochrome aa3 in newborn lambs exposed to hypoxia and hypercapnia, and ischemia: a comparison with changes in brain perfusion and O2 metabolism. Early Hum. Dev. 55, 169–182 (1999).

Brown, D. W. et al. Quantitative near infrared spectroscopy measurement of cerebral hemodynamics in newborn piglets. Pediatr. Res. 51, 564–570 (2002).

Howlett, J. A. et al. Cerebrovascular autoregulation and neurologic injury in neonatal hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatr. Res. 74, 525–535 (2013).

Pryds, O., Greisen, G., Lou, H. & Friis-Hansen, B. Vasoparalysis associated with brain damage in asphyxiated term infants. J. Pediatr. 117, 119–125 (1990).

Alward, C. T., Hook, J. B., Helmrath, T. A., Mattson, J. C. & Bailie, M. D. Effects of asphyxia on cardiac output and organ blood flow in the newborn piglet. Pediatr. Res. 12, 824–827 (1978).

Jensen, A., Garnier, Y. & Berger, R. Dynamics of fetal circulatory responses to hypoxia and asphyxia. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 84, 155–172 (1999).

Yamaguchi, K. et al. Evolving changes in fetal heart rate variability and brain injury after hypoxia–ischaemia in preterm fetal sheep. J. Physiol. 596, 6093–6104 (2018).

Popescu, M. R. et al. Getting an early start in understanding perinatal asphyxia impact on the cardiovascular system. Front. Pediatr. 8, 68–68 (2020).

Galinsky, R. et al. Sustained sympathetic nervous system support of arterial blood pressure during repeated brief umbilical cord occlusions in near-term fetal sheep. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 306, R787-795 (2014).

Galinsky, R. et al. Magnesium sulphate and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular adaptations to asphyxia in preterm fetal sheep. J. Physiol. 594, 1281–1293 (2016).

Ikeda, T. et al. Fetal heart rate patterns in postasphyxiated fetal lambs with brain damage. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 179, 1329–1337 (1998).

López-Herce, J. et al. Correlations between hemodynamic, oxygenation and tissue perfusion parameters during asphyxial cardiac arrest and resuscitation in a pediatric animal model. Resuscitation 82, 755–759 (2011).

Milej, D., Abdalmalak, A., Rajaram, A. & St Lawrence, K. Direct assessment of extracerebral signal contamination on optical measurements of cerebral blood flow, oxygenation, and metabolism. Neurophotonics 7, 045002 (2020).

Kovacsova, Z., Bale, G., Mitra, S., Lange, F. & Tachtsidis, I. Absolute quantification of cerebral tissue oxygen saturation with multidistance broadband NIRS in newborn brain. Biomed. Opt. Express 12, 907–925 (2021).

Kienle, A., Glanzmann, T., Wagnieres, G. & van der Bergh, H. Investigation of two-layered turbid media with time-resolved reflectance. Appl. Opt. 37, 6852–6862 (1998).

Kienle, A. et al. Noninvasive determination of the optical proper ties of two-layered turbid media. Appl. Opt. 37, 779–791 (1998).

Ijichi, S. et al. Quantification of cerebral hemoglobin as a function of oxygenation using near-infrared time-resolved spectroscopy in a piglet model of hypoxia. J. Biomed. Opt. 10, 024026 (2005).

Hueber, D. M. et al. Non-invasive and quantitative near-infrared haemoglobin spectrom etry in the piglet brain during hypoxic stress, using a frequency domain multidistance instrument. Phys. Med. Biol. 46, 41–62 (2001).

Fantini, S. et al. Non-invasive optical monitoring of the newborn piglet brain using continuous wave and frequency-domain spectroscopy. Phys. Med. Biol. 44, 1543–1563 (1999).

Szakmar, E., Jermendy, A. & El-Dib, M. Respiratory management during therapeutic hypothermia for hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy. J. Perinatol. 39, 763–773 (2019).

Pappas, A. et al. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network Hypocarbia and adverse outcome in neonatal hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy. J. Pediatr. 158, 752–758 (2011).

Demarest, T. G. et al. Sex-dependent mitophagy and neuronal death following rat neonatal hypoxia–ischemia. Neuroscience 335, 103–113 (2016).

Mirza, M. A., Ritzel, R., Xu, Y., McCullough, L. D. & Liu, F. Sexually dimorphic outcomes and inflammatory responses in hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy. J. Neuroinflamm. 12, 32 (2015).

Ijichi, S. et al. Developmental changes of optical properties in neonates determined by near-infrared time-resolved spectroscopy. Pediatr. Res. 58, 568–573 (2005).

Funding

This study was financially supported by JSPS KAKENHI grants (25461647, 25860911, 15KK0311, 16H06276, 16K10092, 16K19685, 17K10178, 19K08253, 19K08349, 20K08159, and 20H00102), Kagawa University Faculty of Medicine School of Medicine Alumni Association Sanjukai Research Aid grants (25-2, 29-2, and R1-1), and The Foreign Student Scholarship of Honjo International Scholarship Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.M., S.N., and T.K. designed the study and drafted the article. Y.H., Y.N., M.A, and K.K. performed the animal experiments. A.M., T.W., and Y.H. performed the data analysis. T.M., S.N., Y.K., and T.K. critically revised the manuscript and contributed to the final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mitsuie, T., Nakamura, S., Htun, Y. et al. Cerebral blood volume increment after resuscitation measured by near-infrared time-resolved spectroscopy can estimate degree of hypoxic–ischemic insult in newborn piglets. Sci Rep 11, 13096 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92586-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92586-1

This article is cited by

-

Conflicting findings on the effectiveness of hydrogen therapy for ameliorating vascular leakage in a 5-day post hypoxic-ischemic survival piglet model

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Cerebral hemodynamic response during the resuscitation period after hypoxic-ischemic insult predicts brain injury on day 5 after insult in newborn piglets

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.