Abstract

The St Gallen Conference endorsed in 2013 a series of recommendations on early breast cancer treatment. The main purpose of this article is to ascertain the clinical factors associated with St Gallen-2013 recommendations accomplishment. A cohort of 1152 breast cancer cases diagnosed with pathological stage < 3 in Spain between 2008 and 2013 was begun and then followed-up until 2017/2018. Data on patient and tumour characteristics were obtained from medical records, as well as their first line treatment. First line treatments were classified in three categories, according on whether they included the main St Gallen-2013 recommendations, more than those recommended or less than those recommended. Multinomial logistic regression models were carried out to identify factors associated with this classification and Weibull regression models were used to find out the relationship between this classification and survival. About half of the patients were treated according to St Gallen recommendations; 21% were treated over what was recommended and 33% received less treatment than recommended. Factors associated with treatment over the recommendations were stage II (relative risk ratio [RRR] = 4.2, 2.9–5.9), cancer positive to either progesterone (RRR = 8.1, 4.4–14.9) or oestrogen receptors (RRR = 5.7, 3.0–11.0). Instead, factors associated with lower probability of treatment over the recommendations were age (RRR = 0.7 each 10 years, 0.6–0.8), poor differentiation (RRR = 0.09, 0.04–0.19), HER2 positive (RRR = 0.46, 0.26–0.81) and triple negative cancer (RRR = 0.03, 0.01–0.11). Patients treated less than what was recommended in St Gallen had cancers in stage 0 (RRR = 21.6, 7.2–64.5), poorly differentiated (RRR = 1.9, 1.2–2.9), HER2 positive (RRR = 3.4, 2.4–4.9) and luminal B-like subtype (RRR = 3.6, 2.6–5.1). Women over 65 years old had a higher probability of being treated less than what was recommended if they had luminal B-like, HER2 or triple negative cancer. Treatment over St Gallen was associated with younger women and less severe cancers, while treatment under St Gallen was associated with older women, more severe cancers and cancers expressing HER2 receptors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

From 1995 on, many relevant advances in early breast cancer (BC) treatment have contributed to the improvement in patient survival. For instance, the emergence of anthracycline1 and taxane-based therapies2 and the identification of intrinsic subtypes3. Several guidelines for treating breast cancer patients have been published, although their recommendations differ only marginally4. In this regard, the 12th and 13th St Gallen International Breast Cancer Conference Expert Panel took place in 2011 and 2013, respectively; it endorsed a series of recommendations on early BC treatment5,6. We hereby briefly summarize St Gallen-2013 recommendations according to BC subtypes that are almost identical to those formulated in the previous meeting. Firstly, the Conference agreed in a clinico-pathological surrogate definition of intrinsic BC subtypes and secondly, the Conference stated systemic treatment recommendations for each subtype. In this regard, patients with luminal A-like BC should be treated with endocrine therapy, although cytotoxics may be added in the case of selected patients. Patients with luminal B-like (HER2 negative) BC should be treated with endocrine therapy and cytotoxics should be added for most of them. Patients with luminal B-like (HER2 positive) BC should receive cytotoxics, anti-HER2 and endocrine therapy; patients with HER2 positive (non-luminal) BC should receive cytotoxics and anti-HER2 and patients with triple negative (basal-like) BC should be treated with cytotoxics. It is noteworthy, that St Gallen panel was not unanimous in most of its decisions and it remarked that its recommendations were not just a blind guide; instead, “detailed decisions on treatment will, as always, involve clinical considerations of disease extent, host factors, patient preferences and social and economic constraints”5.

Several studies have shown adherence to guidelines for early stage BC diverged between countries7 and tumour characteristics; triple negative breast cancer7,8 and hormone receptors-negative HER2 positive9 being the subgroups with lower adherence. Older women are more likely to receive non-guideline adherent treatment leading to poorer survival rates7,10,11. Socio-economic status has been found to be associated to differences in guideline compliance in the US12,13,14 and to less extent in The Netherlands15.

The MCC-Spain breast cancer cohort recruited 1738 women with recent diagnosis of breast cancer in ten Spanish provinces between 2008 and 2013, which were subsequently followed-up until 2017 and 2018. In this paper, our objectives are: (1) to ascertain the clinical factors associated with St Gallen-2013 recommendations accomplishment, (2) to investigate whether there are differences by age and intrinsic BC subtype regarding St Gallen fulfilment, and (3) to examine the impact St Gallen non-fulfilment may have on survival with breast cancer. As most women in MCC-Spain were recruited before the 13th St Gallen Conference, St Gallen recommendations cannot be interpreted as a gold standard; therefore, our purpose is not to perform an audit but to identify patterns in actual clinical practice.

Methods

MCC-Spain BC cohort: setting and patients

MCC-Spain was born as a case–control study on colorectal, breast, prostate and gastric cancers and chronic lymphoid leukaemia16. Later on, the colorectal, breast and prostate cancer cases recruited in the case–control phase were incepted in three cancer-specific cohorts in order to ascertain clinical, genetic and epidemiological factors associated with prognosis17. From here on, we only refer to the breast cancer cohort.

This research was performed according to the standards required by the institutional research committees and the Declaration of Helsinki (last amendment, Fortaleza, 2013). The protocol of MCC-Spain was approved by each of the ethics committees of the participating institutions16. The specific study reported here was approved by the Ethical Committee of Clinical Research of Asturias, Barcelona, Cantabria, Girona, Gipuzkoa, Huelva, León, Madrid, Navarra and Valencia. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Women were included in the study cohort if they suffered an incident of pathologically confirmed breast cancer in the 2008–2013 period. After signing an informed consent, 1738 women were recruited in ten Spanish provinces (Asturias, Barcelona, Cantabria, Gipuzkoa, Girona, Huelva, León, Madrid, Navarra y Valencia) and were interviewed by trained personnel in order to gather demographic and epidemiological information17. Women with breast cancer in stages 0, I or II were included in this analysis (1214 patients).

Tumour characteristics

Tumour characteristics at diagnosis were obtained from medical records. They included grade of differentiation (I: well, II: moderately, III: poorly differentiated), histological type (ductal, lobular, papillary, others), pathological stage according to TNM, presence or absence of oestrogen receptors, progesterone receptors and HER2 receptors, as well as other immunohistochemical properties when available (Ki-67, for instance)17. Intrinsic subtypes were determined according to St Gallen clinico-pathological surrogate definitions (Supplementary Table 1). A tumour was considered luminal A-like if it had positive oestrogen and progesterone receptors, HER2 negative and Ki-67 low. In this regard, tumours without Ki-67 determination were considered Ki-67 low for classification purposes if it was grade I or II, and Ki-67 high if it was grade III, as grade III is indicative of high proliferative activity, according to Curigliano et al.18. A tumour was classified as luminal B-like if (1) it had positive oestrogen receptors, HER2 negative and Ki-67 high or negative progesterone receptor or (2) positive oestrogen receptors and positive HER2. A cancer was considered HER2 positive (non-luminal) if it was oestrogen and progesterone receptors negative and HER2 receptors positive. Finally, tumours with oestrogen, progesterone and HER2 receptors negative were classified as triple negative.

First-line treatment

Data on first-line treatment was obtained from medical records. They could include type of surgery (conservative/mastectomy), endocrine therapy, chemotherapy, anti-HER2 therapy or radiotherapy. Treatments other than surgery were classified as neoadjuvant, adjuvant or palliative, according to their purpose.

Classification according to St Gallen-2013

First-line systemic treatments were classified into three groups (In-, Over- and Under St Gallen) according to the adherence to St Gallen-2013 recommendations as follows.

-

In St Gallen: A treatment was considered “In St Gallen” if it consisted in exactly the main St Gallen recommendation for that patient (Supplementary Table 1). For instance, a woman with breast cancer oestrogen-receptor positive, progesterone-receptor positive and HER2 negative receiving just surgical treatment + endocrine therapy.

-

Over St Gallen: A treatment was considered “Over St Gallen” if the woman received the main St Gallen recommendation for her cancer plus some additional therapy. For instance, a woman with breast cancer oestrogen-receptor positive, progesterone-receptor positive and HER2 negative receiving surgical treatment + endocrine therapy + anti-HER2 therapy.

-

Under St Gallen: A treatment was considered “Under St Gallen” if the woman did not receive the main St Gallen recommendation for her cancer (in spite of whether she received additional treatments included in the main recommendation or not). For example, a woman with breast cancer oestrogen-receptor positive, progesterone-receptor positive and HER2 negative receiving surgical treatment + chemotherapy, but not endocrine therapy.

In order to analyse the reliability of the above indicated classification, two independent evaluators (MM and JA-M) applied it to a randomly selected 50-woman subsample, reaching a Cohen’s kappa = 0.76.

Follow-up for ascertaining the vital status was carried out in 2017 and 2018 by reviewing medical records, contacting women by phone and for women without contact with the hospital in the previous three months, by consulting the Spanish National Index of Death.

Statistical analysis

The association between age or tumour characteristics and St Gallen fulfilment was analysed using multinomial logistic regression as the effect variable (St Gallen) has three categories; results—adjusted for age at diagnosis and hospital—are presented as relative risk ratios (RRR) with 95% confidence intervals. Overall survival is presented using Kaplan–Meier estimators. The association of St Gallen fulfilment and survival was analysed separately for each intrinsic subtype using Weibull regression adjusted for age at diagnosis, hospital, grade of differentiation and pathological stage. Weibull regression was considered adequate as the relationship between log[− log(survival probability)] and log(time of follow-up) was approximately linear. For this analysis, event was defined as death and patients were censored if they were alive at the end of follow-up. Weibull regression results are presented as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals. A complementary Weibull analysis was carried out where the event was distant recurrence or dead (the first that happened); patients alive and without distant recurrence at the end of follow-up were considered censored. All statistical analyses were performed with the Stata 16/SE software (Stata Co., College Station, Tx, US).

Results

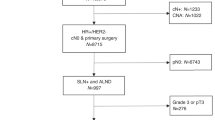

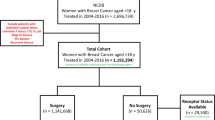

The study sample is described in Table 1 and the patient flow chart in Fig. 1. Out of 1242 breast cancers in stages 0, I or II, intrinsic subtype was established in 1152 cases; luminal A-like was the most frequent subtype (687 cases, 60%), 324 cases (28%) were luminal B-like, 52 (5%) were HER2 (non-luminal) and 89 (8%) were triple negative. The intrinsic breast cancer subtype could not be determined in 90 cases (7%). 56 were hormonal receptors positive, but results on HER2 receptor were not available. Therefore, they could be classified as luminal, but we could not ascertain if they were luminal A or luminal B. Eight cases were hormonal receptors negative, but—again—results on HER2 receptors were not available. Therefore, those cases were non-luminal, but we could not determine if they were HER-2 positive or triple negative. In 26 cases, we had no data on hormonal or HER2 receptors. Recurrence in the follow-up was found in 86 women (7.5%), 52 of them being distant. 94 (8.9%) women died in the follow-up.

Out of 1152 breast cancer cases with established intrinsic subtype, 523 (45.4%) were treated In St Gallen, 243 (21.1%) Over St Gallen and 386 (33.5) Under St Gallen. Over St Gallen was more frequent in patients with luminal A cancer (219 out of 687 cases, 31.9%) and Under St Gallen was more frequent in patients with luminal B cancer (173 out of 324 cases, 53.4%) (Table 2).

Table 3 provides the factors associated with Over St Gallen treatment. Women with breast cancer in stage II had more than four times the probability of being treated Over St Gallen (RRR = 4.15, 95% CI 2.90–5.94) compared to women with breast cancer in stage I. Cancers positive to either progesterone or oestrogen receptors also increased the likelihood of treatment Over St Gallen. Factors associated with lower probability of being treated Over St Gallen were age (RRR = 0.70, 95% CI 0.62–0.81 for each 10 years more), poorly differentiated cancers (RRR = 0.09, 95% CI 0.04–0.19), HER2 positive cancers (RRR = 0.46, 95% CI 0.26–0.81) and luminal B and triple negative subtypes (RRR = 0.07, 95% CI 0.04–0.13 and RRR = 0.03, 95% CI 0.01–0.11, respectively.) Regarding differences according to age by tumoral subtype, women over the age of 65 had a lower probability of being treated Over St Gallen if they had luminal A-like cancer than those under 65 (Fig. 2a).

Relative risk ratios (RRR) for women over 65 years old compared with women under 65 years old of being treated Over (a) or Under (b) St Gallen. In (a), RRR > 1 indicates that women over 65 were more likely to be treated Over St Gallen than women under 65 years old, while in (b), RRR > 1 indicates that women over 65 were more likely to be treated Under St Gallen than women under 65. Results on HER2 + tumours treated Over St Gallen are not shown as analysis did not converge.

Under St Gallen treatment was more frequent in patients with pathological stage 0 (RRR = 21.6, 95% CI 7.221–64.5), poorly differentiated cancer (RRR = 1.88, 95% CI 1.21–2.93) or missing grade of differentiation (RRR = 3.72, 95% CI 2.21–6.29), cancers positive to HER2 receptors (RRR = 3.44, 95% CI 2.40–4.93) and luminal B and HER2 intrinsic subtypes (RRR = 3.63, 95% CI 2.59–5.09 and RRR = 4.38, 95% CI 2.23–8.60, respectively) (Table 4). Compared with women under 65, those 65 years or over had a higher probability of being treated Under St Gallen if they suffered a luminal B-like, Her2 (non-luminal) or triple negative cancer (Fig. 2b).

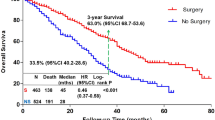

The follow-up accounted for 7730 patient-years. 94 women died in the follow-up, making a linearized mortality rate of 1.22 per 100 patient-years (95% CI 0.98–1.49). Crude 5-year overall survival was 94.2%; survival at 5 years was approximately equal for patients treated In St Gallen and Under St Gallen and about 4% higher for patients Over St Gallen (Table 5, Fig. 3). After adjusting for age, hospital, grading and stage at diagnosis, Under St Gallen treatment was associated with a higher probability of dying in women with triple negative breast cancer (HR = 4.65, 95% CI 0.87–24.8), but not in other breast cancer subtypes (Suppl. Table 2). Results from Weibull regression using the combined event distant recurrence or dead (Suppl. Table 3) were similar to those founded for overall survival (Suppl. Table 2).

Discussion

According to our results, systemic treatment of early breast cancer fully accomplished St Gallen-2013 recommendations in about 50% patients; two out of nine were treated Over St Gallen and three in ten were treated Under St Gallen. This variability was related to both age and tumour characteristics. Regarding age, older women tended to have less likelihood of being treated Over St Gallen (30% lower probability each ten years) and more likelihood, although non-statistically significant- to be treated Under St Gallen (8% higher probability each ten years). Altogether, more severe tumours (stage II, poorly differentiated, hormone receptors negative, basal-like) were less likely to be treated Over St Gallen. Most severity factors, except triple negative tumour, were associated with higher probability of being treated Under St Gallen.

Interpreting these results is not straightforward. First of all, St Gallen recommendations were not just a “must”. Instead, they should have been individualized in the light of both patient and clinical information. In this regard, further St Gallen International Breast Cancer Conferences have focused on a practical approach of therapies to individual patients19 as well as identifying patients that could benefit from escalating or de-escalating treatments18. Our results cannot be interpreted as an audit of accomplishing clinical guides as patients in our cohort were recruited from 2008 to 2013 (i.e., before St Gallen recommendations were stated); instead, our comparison of actual treatments with St Gallen is a portrayal on the way breast cancer patients were treated as compared to the state-of-the-art about the same time.

Apart from St Gallen recommendations, several organizations have delivered their own guidelines on breast cancer treatment20,21, although they usually differ only marginally4. A main factor related with deviations from guidelines is woman’s age. Several studies have described that older women are less likely to receive or be offered standard treatment10,11,22,23,24, leading to be given adjuvant chemotherapy less frequently25,26. Regarding endocrine therapy, between-countries large variation has been observed in women over 70 years old, without variation in relative survival, which suggests possible overtreatment27; women under 50 have been found less adherent to endocrine therapy28. According to our results, treatment in Spanish women with breast cancer differed between those over and under 65 years of age. The latter being less prone to be treated Over St Gallen if suffering luminal A-like and more prone to be treated Under St Gallen if suffering any other intrinsic breast cancer subtype (luminal B-like, Her2 non-luminal or triple negative), meaning that in all subtypes, women over 65 received less treatment on average. There are several issues regarding recommendations for treating early breast cancer in women over 65 or 70; firstly, breast cancers in older women tend to be less aggressive29. Secondly, older women are usually under-represented in clinical trials30,31, which makes it more difficult to establish standards for treating these patients32. Thirdly, Spanish women aged 65 and 70 have life expectancy of 23.0 and 18.7 years, respectively33; therefore, short expectancy of life cannot be argued for supporting undertreatment.

Women with luminal A-like tumours were more probably treated Over St Gallen than women with any other intrinsic subtype. In this regard, the main Over St Gallen treatment in women with luminal A-like tumours was chemotherapy. Whether hormone-positive, HER2-negative and node-negative patients would benefit from chemotherapy remains controversial; a 21-gene score (Oncotype DX, Genomic Health, Redwood City, CA) has been proven to have predictive value for recurrence34,35 and has been endorsed by several scientific societies20,21. TAILORx trial has shown that women scoring Oncotype DX ≤ 25 can receive hormone therapy alone, while women scoring > 25 should benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy36,37. By the time our patients were recruited, genetic testing was not of general use. However, it has been recently shown that combining information from age, tumour size, grading, progesterone receptors and histological type can establish risk of recurrence as from Oncotype DX38. When applying Orucevic et al. model to our patients, only one in ten women receiving chemotherapy against luminal A-like tumour had a probability higher than 20% of having a high risk of recurrence, which suggests most of them had been over treated (results not shown).

Our results could imply some clinical considerations. First of all, St Gallen recommendations, as well as guidelines issued by other organizations20,21, could inform about treatment of patients with BC, although clinicians should take decisions on an individual basis. In this regard, the trend we describe towards less aggressive treatment in older women is noteworthy. Such a conservative decision could not be justified by general considerations (e.g., expectancy of life in older women), but on specific individual grounds (e.g., comorbidities or other factors limiting patient’s benefit). Secondly, the idea of BC being a homogenous disease requiring homogenous treatment is largely outdated. However, we lay out the fact that less aggressive BC tend to be treated over the standard recommendations while those that are more aggressive are treated under the recommendations, which makes treatment of biologically different BC as if they were alike. The clinical consequences of it would require further research.

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, our classification on St Gallen recommendation accomplishment is somewhat subjective; we have found the between-raters reliability to be high, but there is still room for misclassification. Secondly, less severe cancers usually require less treatment and so, are more likely to be Over St Gallen, while more severe cancers require more treatment and are more likely to be Under St Gallen. Thirdly, our follow-up is still short as 5-year survival in early BC is around 90%. Fourthly, comorbidities were not recorded, which may affect whether clinical guidelines are closely followed or not. In fifth place, our number of patients—although high for general analysis—was not enough to study interactions or to analyse the effect of St Gallen unfulfillment in depth. In this regard, several results of our survival analysis are based on small figures (Suppl. Table 2), which makes them little reliable. Our study also has some strengths. Firstly, information on more than one thousand patients was obtained in a standardized way without acknowledgment of this paper’s hypothesis; therefore, misclassification on clinical characteristics or first-line treatment could only introduce a non-differential bias. Secondly, follow-up was performed prospectively, which guarantees high quality follow-up data.

In conclusion, about 50% women with early BC were treated according to St Gallen recommendations. Treatment Over St Gallen was associated with younger women and less severe cancers (luminal A-like, well-differentiated, stage I) and treatment Under St Gallen was associated with older women, more severe cancers and cancers expressing HER2 receptors. No differences in overall survival were observed between the Under St Gallen group compared to the adherent group, which implies that there were no great deviations from “standard” treatment in our context. Finally, the improvement in survival observed in the Over St Gallen group supports the decision taken by the medical team treating these patients.

References

Clarke, M. et al. Effects of Chemotherapy and Hormonal Therapy for Early Breast Cancer on Recurrence and 15-Year Survival: An Overview of the Randomised Trials (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2005).

Slamon, D. et al. Adjuvant trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 1273–1283 (2011).

Sørlie, T. et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 10869–10874 (2001).

Wolters, R. et al. A comparison of international breast cancer guidelines—Do the national guidelines differ in treatment recommendations?. Eur. J. Cancer 48, 1–11 (2012).

Goldhirsch, A. et al. Personalizing the treatment of women with early breast cancer: highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2013. Ann. Oncol. 24, 2206–2223 (2013).

Goldhirsch, A. et al. Strategies for subtypes-dealing with the diversity of breast cancer: Highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2011. Ann. Oncol. 22, 1736–1747 (2011).

Schwentner, L. et al. Adherence to treatment guidelines and survival in triple-negative breast cancer: A retrospective multi-center cohort study with 9156 patients. BMC Cancer 13, 487 (2013).

Schwentner, L. et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: The impact of guideline-adherent adjuvant treatment on survival—A retrospective multi-centre cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 132, 1073–1080 (2012).

Ebner, F. et al. Tumor biology in older breast cancer patients—What is the impact on survival stratified for guideline adherence? A retrospective multi-centre cohort study of 5378 patients. The Breast 24, 256–262 (2015).

Bastiaannet, E. et al. Breast cancer in elderly compared to younger patients in the Netherlands: Stage at diagnosis, treatment and survival in 127,805 unselected patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 124, 801–807 (2010).

Malik, M. K., Tartter, P. I. & Belfer, R. Undertreated breast cancer in the elderly. J. Cancer Epidemiol. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jce/2013/893104/. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/893104.

Griggs, J. et al. Social and racial differences in selection of breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy regimens. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 25, 2522–2527 (2007).

Wu, T.-Y. et al. Admission rates and in-hospital mortality for hip fractures in England 1998 to 2009: time trends study. J. Public Health (Oxf.) 33, 284–291 (2011).

Dreyer, M. S., Nattinger, A. B., McGinley, E. L. & Pezzin, L. E. Socioeconomic status and breast cancer treatment. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 167, 1–8 (2018).

Kuijer, A. et al. The influence of socioeconomic status and ethnicity on adjuvant systemic treatment guideline adherence for early-stage breast cancer in the Netherlands. Ann. Oncol. 28, 1970–1978 (2017).

Castaño-Vinyals, G. et al. Population-based multicase-control study in common tumors in Spain (MCC-Spain): Rationale and study design. Gac. Sanit. 29, 308–315 (2015).

Alonso-Molero, J. et al. Cohort profile: The MCC-Spain follow-up on colorectal, breast and prostate cancers: Study design and initial results. BMJ Open 9:e031904. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031904 (2019).

Curigliano, G. et al. De-escalating and escalating treatments for early-stage breast cancer: The St Gallen International Expert Consensus Conference on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2017. Ann. Oncol. 28, 1700–1712 (2017).

Coates, A. S. et al. Tailoring therapies—Improving the management of early breast cancer: St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2015. Ann. Oncol. 26, 1533–1546 (2015).

Harris, L. N. et al. Use of biomarkers to guide decisions on adjuvant systemic therapy for women with early-stage invasive breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 1134–1150 (2016).

Gradishar, W. J., et al. guidelines index table of contents discussion. Breast Cancer 216 (2019). Breast Cancer, Version 3.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw., 18(4), 452–478. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2020.0016 (2020).

Bouchardy, C., Rapiti, E., Blagojevic, S., Vlastos, A.-T. & Vlastos, G. Older female cancer patients: Importance, causes, and consequences of undertreatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 1858–1869 (2007).

Lavelle, K. et al. Non-standard management of breast cancer increases with age in the UK: A population based cohort of women ≥ 65 years. Br. J. Cancer 96, 1197–1203 (2007).

Guevara, M. et al. Care patterns and changes in treatment for nonmetastatic breast cancer in 2013-2014 versus 2005: a population-based high-resolution study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 26 Joining forces for better cancer registration in Europe:S215–S222. (2017) https://doi.org/10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000379 (2017).

DeMichele, A., Putt, M., Zhang, Y., Glick, J. H. & Norman, S. Older age predicts a decline in adjuvant chemotherapy recommendations for patients with breast carcinoma. Cancer 97, 2150–2159 (2003).

Ring, A. et al. The treatment of early breast cancer in women over the age of 70. Br. J. Cancer 105, 189–193 (2011).

Derks, M. G. M. et al. Variation in treatment and survival of older patients with non-metastatic breast cancer in five European countries: A population-based cohort study from the EURECCA Breast Cancer Group. Br. J. Cancer 119, 121–129 (2018).

Font, R. et al. Influence of adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy on disease-free and overall survival: A population-based study in Catalonia, Spain. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 175, 733–740 (2019).

Diab, S. G., Elledge, R. M. & Clark, G. M. Tumor characteristics and clinical outcome of elderly women with breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 92, 550–556 (2000).

Lewis, J. H. et al. Participation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer clinical trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 21, 1383–1389 (2003).

de Glas, N. A. et al. Choosing relevant endpoints for older breast cancer patients in clinical trials: An overview of all current clinical trials on breast cancer treatment. Breast Cancer Res Treat 146, 591–597 (2014).

Biganzoli, L. et al. Management of elderly patients with breast cancer: Updated recommendations of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) and European Society of Breast Cancer Specialists (EUSOMA). Lancet Oncol. 13, e148-160 (2012).

INE. Indicadores demográficos básicos. Consultado el 18 de diciembre de 2020, en https://www.ine.es/ss/Satellite?L=es_ES&c=INESeccion_C&cid=1259926380048&p=1254735110672&pagename=ProductosYServicios/PYSLayout (2020).

Paik, S. et al. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 2817–2826 (2004).

Paik, S. et al. Gene expression and benefit of chemotherapy in women with node-negative, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, 3726–3734 (2006).

Stemmer, S. M. et al. Clinical outcomes in patients with node-negative breast cancer treated based on the recurrence score results: Evidence from a large prospectively designed registry. NPJ Breast Cancer 3, 33 (2017).

Sparano, J. A. et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy guided by a 21-gene expression assay in breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 111–121 (2018).

Orucevic, A., Bell, J. L., King, M., McNabb, A. P. & Heidel, R. E. Nomogram update based on TAILORx clinical trial results—Oncotype DX breast cancer recurrence score can be predicted using clinicopathologic data. Breast 46, 116–125 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients and families for their participation in the MCC-Spain study, as well as all study centers and collaborators.

Funding

Biological samples were stored at the biobanks supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III-FEDER: Parc de Salut MAR Biobank (MARBiobanc) (RD09/0076/00036), ‘Biobanco La Fe’ (RD 09 0076/00021) and FISABIO Biobank (RD09 0076/00058), as well as at the Public Health Laboratory of Gipuzkoa, the Basque Biobank, the ICOBIOBANC (sponsored by the Catalan Institute of Oncology), the IUOPA Biobank of the University of Oviedo, and the ISCIII Biobank. SNP genotyping services were provided by the Spanish ‘Centro Nacional de Genotipado’ (CEGEN-ISCIII). We thank all the subjects who participated in the study and all MCC-Spain collaborators. This work was supported by the ‘Acción Transversal del Cancer’, approved by the Spanish Ministry Council on the 11th October 2007, by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, co-founded by FEDER funds-‘a way to build Europe’ (Grants PI08/1770, PI08/0533, PI08/1359, PI09/00773, PI09/01286, PI09/01903, PI09/02078, PI09/01662, PI11/01403, PI11/01889, PI11/00226, PI11/01810, PI11/02213, PI12/00488, PI12/00265, PI12/01270, PI12/00715, PI12/00150, PI14/01219, PI14/00613, and PI15/00069). Support was also provided by the Fundación Marqués de Valdecilla (Grant API 10/09); the Junta de Castilla y León (Grant LE22A10-2); the Consejería de Salud of the Junta de Andalucía (2009-S0143); the Conselleria de Sanitat of the Generalitat Valenciana (Grant AP 061/10); the Recercaixa (Grant 2010ACUP 00310); the Regional Government of the Basque Country; the Consejería de Sanidad de la Región de Murcia; European Commission grants FOOD-CT-2006-036224-HIWATE; the Spanish Association Against Cancer (AECC) Scientific Foundation; the Catalan Government DURSI (Grant 2014SGR647); the Fundación Caja de Ahorros de Asturias; the University of Oviedo; Societat Catalana de Digestologia; and COST action BM1206 Eucolongene.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: I.G.A., T.D.S. and J.L.L. Statistical analysis: I.G.A., T.D.S. and J.L.L. Coordination of substudy sites, recruitment and acquisition of data: I.G.A., T.D.S., M.M., B.P.G., M.G., P.A., M.S., A.J.M.T., J.A.M., V.M., C.S.C., A.M.B., J.A., R.M.G., M.F.O., O.S.G., G.C.V., L.G.M., C.M.I., N.A.,. M.K., M.P. and J.L.L. Drafting of the manuscript: I.G.A., T.D.S. and J.L.L. Contributions to the final version of the manuscript were made by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gómez-Acebo, I., Dierssen-Sotos, T., Mirones, M. et al. Adequacy of early-stage breast cancer systemic adjuvant treatment to Saint Gallen-2013 statement: the MCC-Spain study. Sci Rep 11, 5375 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84825-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84825-2

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.