Abstract

High-resolution transmission electron microscopy and atom probe tomography are used to characterize the initial passivation and subsequent intergranular corrosion of degraded grain boundaries in a model Ni-30Cr alloy exposed to 360 °C hydrogenated water. Upon initial exposure for 1000 h, the alloy surface directly above the grain boundary forms a thin passivating film of Cr2O3, protecting the underlying grain boundary from intergranular corrosion. However, the metal grain boundary experiences severe Cr depletion and grain boundary migration during this initial exposure. To understand how Cr depletion affects further corrosion, the local protective film was sputtered away using a glancing angle focused ion beam. Upon further exposure, the surface fails to repassivate, and intergranular corrosion is observed through the Cr-depleted region. Through this combination of high-resolution microscopy and localized passive film removal, we show that, although high-Cr alloys are resistant to intergranular attack and stress corrosion cracking, degradation-induced changes in the underlying metal at grain boundaries make the material more susceptible once the initial passive film is breached.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pressurized water reactors (PWRs) use high-temperature (~280–360 °C) hydrogenated water to transfer heat from the reactor core to a steam generator through a primary water loop. Nickel-base alloys were historically selected for many structural components in PWRs away from the core neutron flux (e.g., steam generator tubes) owing to their general resistance to aqueous corrosion. In this hydrogenated water, Ni is thermodynamically stable in its metallic state1, and selective oxidation of the less noble alloying elements (e.g., Cr, Fe, Mn, etc.) is typically observed2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Additionally, the operating temperature of PWRs results in a B-type diffusion regime9,10 that strongly favors grain boundary diffusion over bulk diffusion. This combination of temperature and water chemistry creates an ideal environment for selective and penetrative intergranular (IG) oxidation of susceptible alloys11,12. For example, Alloy 600 (Ni-16Cr-9Fe), used in steam generator tubes and other locations, can be highly susceptible to intergranular stress corrosion cracking (IGSCC) under service conditions13,14,15,16. The precise SCC mechanism underpinning this behavior is still debated16,17,18,19,20, but most recognize that intergranular oxidation and embrittlement strongly correlate with the IGSCC response of Alloy 600.

Compared to Alloy 600, the higher-Cr concentration Alloy 690 (Ni-30Cr-9Fe) exhibits far greater resistance to IGSCC in high-temperature hydrogenated water. Many Alloy 600 components in PWRs have thus been replaced with Alloy 690 components in the last decades16; these replaced components have an outstanding service record to date21. However, it is important to note that Alloy 690 is not immune to IGSCC. Laboratory SCC tests beginning with a pre-cracked specimen of Alloy 690 have consistently demonstrated low but measurable crack growth rates22,23,24,25, especially in highly cold-worked conditions26,27,28,29,30. Results from complementary SCC initiation testing of Alloy 690 are more complex, with some specimens showing no detectable cracking after years of testing20,27,31,32,33.

One of the unique features of corrosion and SCC of Alloy 690 in high-temperature hydrogenated water is the apparent absence of the preferential intergranular oxidation that is ubiquitous in the lower Cr Alloy 600 material. In static corrosion coupons, surface corrosion of Alloy 690 in simulated PWR water is characterized primarily by nanoscale transgranular oxide penetrations, likely along dislocations6,34,35,36,37,38. Nearer the grain boundary, these oxide penetrations diminish, replaced instead with a protective nanoscale film of Cr2O3 that prevents oxygen ingress to the underlying grain boundary and adjacent metal. Thus it has been postulated that the superior SCC performance of the 30 at.% Cr Alloy 690 is founded in its resistance to intergranular oxidation, and the SCC mechanism for Alloy 690 and Alloy 600 may be fundamentally different. In particular, the absence of similar intergranular oxidation in Alloy 690 suggests creep or atomic ordering (short or long-range) may play more critical roles in its SCC response23,30,39,40,41,42,43,44.

Despite their oxide morphology differences, the underlying metallic grain boundaries of corroded Alloys 600 and 690, and similarly model Ni-Cr binary alloys, share a common feature: extensive grain boundary Cr depletion. Driven by the selective nature of the reactions with the surrounding water chemistry, Cr is leached from the grain boundary in all cases to form Cr-rich oxides. This grain boundary depletion can extend for many micrometers from the corroded surface. Such long-range Cr diffusion requires Cr grain boundary diffusivity to be several orders of magnitude faster than pure thermal diffusion, suggesting that vacancy injection accelerates Cr diffusivity30. Furthermore, several authors have noted that broad Cr depletion profiles ( ~ hundreds of nanometers wide) form at affected grain boundaries7,45,46,47,48,49,50. These unique profiles are believed to result from diffusion-induced grain boundary migration (DIGM), which is also directly related to the rapid unidirectional Cr diffusion to the oxidation front. In this case, DIGM is driven by the oxidation potential of Cr, which then establishes Cr depletion and a chemical gradient for further Cr diffusion and thus DIGM. DIGM profiles are distinct from the more traditionally recognized thermal sensitization Cr depletion profiles that result from intergranular Cr carbide precipitation during heat treatments51. In thermal sensitization, intergranular Cr carbides precipitate uniformly throughout the material, depleting the grain boundaries of Cr. With time, matrix diffusion of Cr replaces the intergranular Cr depletion, establishing relatively broad (up to micrometer scale) and symmetric Cr depletion profiles to both sides of the grain boundary plane without obvious grain boundary migration. DIGM Cr depletion profiles on the other hand are localized to near the oxidized surface and are highly asymmetric. DIGM depletion profiles are also narrower and extend only ~100 s of nm to one side of the grain boundary plane, frequently undulating from side to side with increasing depth. In DIGM, as Cr diffuses to the reaction front, the grain boundary itself also migrates, leaving a region of Cr-depleted metal in the wake of the grain boundary migration.

Most research on SCC in Ni-base alloys has focused on the role of intergranular oxides and relatively little attention has been given to the impact of the Cr depletion zone along grain boundaries. In this work, we interrogate the effect of DIGM and its associated Cr depletion on the intergranular corrosion of a model Ni-30Cr alloy after artificial removal of its initial passivating film above several grain boundaries.

Results

Initial corrosion response

A highly polished coupon of a high-purity Ni-30Cr binary alloy was exposed to 360 °C hydrogenated, pressurized water in a stainless steel autoclave for 1000 h. To protect the surface oxide during sectioning, a ~ 50 nm film of Ni metal was sputter-deposited onto the surface. Cross-section scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) high-angle annular dark field (HAADF) in Fig. 1(a) reveals a thin oxide layer across the sample surface with no penetrative oxidation down the grain boundary. The bright contrast of the grain boundary region in the STEM HAADF image, in addition to transmission electron microscopy (TEM) bright field (BF) imaging in Fig. 1b, show that the grain boundary has migrated significantly, leaving in its wake an altered alloy composition. Precession electron diffraction (PED) data showing the grain orientations and curvature of the migrated grain boundary are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Note that the random black contrast observed as spots in Fig. 1b in grain 2 are artifacts from the FIB milling process which appear as black spot damage or surface dislocations.

a STEM HAADF and (b) TEM BF images of the exposed surface and migrated grain boundary. c, d STEM EDS mapping of the near the surface away from the grain boundary and corresponding line scan showing a typical duplex oxide structure. e–g STEM EDS maps and linescan collected across the DIGM zone, quantifying near complete Cr depletion across ~60 nm wide region.

STEM energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) was also used to describe the local composition of the altered surface. In Fig. 1c, d, EDS imaging shows that the oxide film formed on the alloy surface exhibits a typical duplex structure, with a ~ 20 nm thick Cr-rich inner oxide (likely Cr2O3) and a Ni/Fe-rich outer oxide. The EDS line scan across the surface oxide shows that Fe from the steel autoclave is present in the outer oxide layer. Above the Fe-rich oxide is the sputter-deposited protective Ni metal film that is partially oxidized. The absence of O penetration or internal oxide formation beneath the Cr-rich inner oxide established that the oxide film protects the underlying metal from further corrosion.

STEM EDS in Fig. 1e–g also reveals more quantitative detail on the altered grain boundary composition. Correlating the STEM HAADF and EDS Cr map, the alloy grain boundary has migrated near the surface from left to right ~60 nm, leaving in its wake substantial Cr depletion down to 0–5 at.% from a matrix concentration of ~30 at.% Cr. Similar Cr depletion and associated grain boundary migration have been observed previously in other Ni-Cr alloys during high-temperature water and steam corrosion and identified as DIGM38,45,46,49,52,53,54,55,56. The Cr depletion extends only to one side (switching from right to left to right) of the original (straight) grain boundary, consistent with a classic DIGM microstructure. The STEM EDS line scan across the DIGM zone (Fig. 1[g]) also shows a shallower Cr gradient across the original grain boundary plane (~60 nm position in the line profile) and a steeper gradient across the current grain boundary plane (~125 nm position in the profile). This is consistent with Cr depletion near the original grain boundary partially being replaced by bulk diffusion from the adjacent metal, while the current grain boundary has not experienced any back diffusion. Furthermore, close inspection of the STEM EDS line profile reveals a slightly higher Cr concentration (~3.5 at.% Cr) from 100 to 120 nm than the region from 60–100 nm (<1.5 at.% Cr), suggesting a slower flux of Cr towards the oxidizing surface with increasing corrosion time.

Atom-probe tomography (APT) was used to further examine the 3D nature of the initial surface oxides and Cr-depleted grain boundary. As illustrated schematically in Fig. 2(a), APT targeted three different regions of the corroded surface: the Cr-depleted grain boundary (b,e), the thin protective oxide formed directly above the grain boundary (c,f), and the less protective oxides formed further from the grain boundary (d,g). In the atom map reconstruction shown in Fig. 2b, a Cr isoconcentration surface (Cr = 22 at.%) delineates regions of Cr depletion from the nominal alloy composition. Simultaneously, these surfaces outline the original and the migrated grain boundary positions that bound the Cr-depleted zone formed in the wake of DIGM. In Fig. 2e, two concentration profiles are overlaid to illustrate the different Cr concentration gradients across the new grain boundary (orange, ~2 nm interfacial width) and original grain boundary (brown, ~5 nm interfacial width). This broader interface at the original grain boundary position reflects 1000 h of thermal Cr bulk diffusion to partially backfill the substantial Cr depletion within the DIGM zone (down to ~5 at.% from ~30 at.% in the surrounding matrix).

a Schematic illustration of initial Ni-30Cr surface corrosion in high-temperature hydrogenated water (adapted from34). b–d Select APT reconstructions from different regions of the initially corroded sample showing (b) Cr-depleted grain boundary and DIGM zone beneath the oxidized surface. c APT reconstruction showing the metal/oxide interface of the surface corrosion immediately adjacent to the DIGM zone. d APT reconstruction of the metal/oxide interface and transgranular penetrative oxidation away from the DIGM zone. e–g APT 1D concentration profiles collected across various interfaces highlighted in (b–d) quantifying composition changes associated with DIGM and the metal/oxide interfaces. In (e) the lighter shades represent the sharp interface of the new grain boundary (line 1) and the darker shades represent the interface at the original grain boundary (line 2).

Figure 2c, f depict atom maps and concentration profiles derived from the thin protective oxide layer formed within ~200 nm of where the grain boundary intersects the exposed surface. The oxide layer is compositionally a good match for Cr2O3 (~1 at.% Ni, 41 at.% Cr and 58 at.% O measured), with only trace amounts of Ni present, in particular, if the typical loss of O from oxides in APT quantification is taken into account57,58,59,60. Beneath this is a thin layer of Cr depletion, reaching a minimum of ~10 at.% Cr, that is ~5 nm wide (defined by 90% of return to Cr2O3 or base alloy Cr concentration respectively). The thickness of the Cr2O3 layer does not appear to match that of the underlying Cr depletion, suggesting that at least some of the Cr found in this oxide originated from the Cr-depleted DIGM zone at the nearby grain boundary and lateral metal/oxide interfacial diffusion. The red 1.5% CrO isoconcentration surface in Fig. 2(c) also shows some discrete Cr-O precipitates within the base alloy, consistent with limited internal oxidation. However, it is puzzling how these oxides could form so deeply within the high-Cr alloy matrix as conventionally internal oxidation is associated with dilute solute alloys, and further studies are needed to fully understand this behavior.

Lastly, Fig. 2d, g shows the much more complex 3D nature of penetrative oxides far from the grain boundary plane intersection. This sample was extracted several micrometers from any apparent grain boundary. Rather than forming a thin, continuous Cr2O3 film, a thick surface oxide and multiple deeper oxide penetrations can be found. The line profile in Fig. 2g illustrates the lack of stoichiometry in the oxides. The O concentration is most consistent with a spinel. The oxide also contains ~5 at.% Fe (from the steel autoclave environment) and ~10 at.% Ni. This is in contrast to the more pure sesquioxide in thin surface oxide in Fig. 2f. The significant Fe penetration confirms the lack of protectivity of the surface oxide film in this region. Lithium, not shown and from the simulated PWR primary water chemistry, is also detected at trace concentration (~0.1 at.%) throughout these oxides. Quantitative analysis (see Supplementary Fig. 5) of the deeper penetrating finger-like oxides below the surface revealed a Cr2O3 composition devoid of Fe and Ni.

Intergranular corrosion after surface oxide removal

The surface oxide over several grain boundaries was removed using a focused ion beam (FIB) at a glancing angle to expose the underlying Cr-depleted grain boundaries. This FIB procedure is further described in the Methods section. Subsequently, the coupon was further corroded (additional 1000 h, 360 °C hydrogenated water), resulting in clear localized corrosion of the re-exposed, Cr-depleted grain boundaries. To examine the sub-surface oxidation response, cross-sections of the grain boundary were exposed with the FIB and imaged with scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Figure 3a shows a schematic of two series of FIB/SEM serial cross-section images along two sections of a single grain boundary: one section exposed for an additional 1000 h with the surface oxide intact, and a second section where the surface oxide was removed before re-exposure. Figure 3b reveals that the surface oxide above the grain boundary with an intact surface oxide still appears thin with no discernable differences in the extent of Cr depletion, DIGM, or oxide thickness versus the initial exposure. Conversely, FIB/SEM serial imaging of the grain boundary where the surface oxide was removed above the DIGM zone (Fig. 3c) shows intergranular oxides. In most cases this oxidation is confined to the Cr depleted DIGM zone closest to the surface. In no case did the oxide extend beyond the cross-over point at which the DIGM direction switched to the other side of the grain boundary and into another grain.

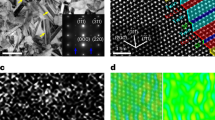

STEM analyses of the intergranular corrosion microstructure and chemistry are presented in Fig. 4. STEM HAADF (Fig. 4[a]) and EDS (Fig. 4[b, c]) images reveal that a Cr-rich surface oxide did reform, but it failed to prevent penetrative oxidation into the Cr-depleted grain boundary and DIGM zone that had formed during the initial exposure. The penetrative oxide is Cr-rich and extends ~750 nm into the re-exposed surface while the Cr depletion along the grain boundary extends much deeper ( > 1 µm) beyond the field of view of the STEM analysis region. The corroded DIGM zone also shows evidence of Ni-rich metallic inclusions. We postulate that Ni is rejected from oxides as they form, resulting in Ni-rich metal islands enveloped by Cr-rich oxide. Closer inspection of the corrosion at the migrated grain boundary plane in Fig. 4d reveals a thin ( ~ 5–10 nm) layer of Cr-rich oxide. A line scan across the thin grain boundary oxide and adjacent corroded DIGM zone is shown in Fig. 4f. Strong localized compositional variations can be associated with the Ni-rich inclusions, the relatively well-defined Cr2O3 layer, and the mixed metal/oxide signal extending into the matrix. This mixed metal/oxide signal coincides with the slightly darker contrast in the STEM HAADF images in Fig. 4a, d and reveals some transgranular Cr-rich oxides extending 20–40 nm from the grain boundary into the surrounding grain 1 alloy matrix. STEM HAADF images as a tilt series are provided in Supplementary Movie 2 for a more comprehensive depiction of the distribution of metal and oxide in this region. Finally, by tilting the alloy matrix to the <112> orientation (Fig. 4[e]) HAADF atomic column imaging reveals the crystallographic orientation relationship between the metal and oxide phases. Assuming the, {111}//{0001}, orientation relationship with the austenite matrix on the metal island in the orientation, the Cr2O3 plane is expressed.

a STEM HAADF of the corroded DIGM zone. b, c STEM EDS elemental maps for Ni/O and Cr/Fe, respectively of the corroded grain boundary. d STEM HAADF of the blue box in (a) showing thin (5–10 nm), continuous oxidation along the grain boundary. e STEM HAADF atomic column image of the yellow box in (d) showing the orientation relationship of the austenitic matrix with the oxide. f STEM EDS line scan 1 as indicated in (d).

Atom probe analysis of the intergranular corrosion upon re-exposure is presented in Fig. 5. Figure 5a shows a schematic of the location the APT needle was extracted from: a volume containing the original grain boundary close to the surface. Figure 5b shows the 3D ion map with isoconcentration surfaces at 22 at.% Cr and 8 ion% CrO outlining the Cr-depleted DIGM zone and the penetrating oxides, respectively. Compositional analysis shown in the line profile in Fig. 5c quantifies the local depleted Cr concentration in this DIGM zone to ~18 at.% Cr, with an interfacial width ~4 nm. This width is consistent with the original grain boundary (in the midst of a composition recovery process) after the initial exposure, although APT could not definitely identify the crystallography of the DIGM zone. The 3D ion map also displays a Cr-rich oxide penetration at the original grain boundary near the top of the reconstruction and again within the DIGM zone towards the lower-right of the reconstruction. The line profile in Fig. 5d reveals an oxide that is not stoichiometric Cr2O3. Instead, the composition was measured to be 42 at. % Cr, 5 at.% Ni, 5 at. % Fe, and 48 at. % O, which suggests either a non-stoichiometric MO or M3O4 phase. Although not thermodynamically stable, such phases and compositions are kinetically possible in oxides grown via solute capture mechanisms61.

a Illustration depicting the microstructure resulting from the re-exposure corrosion and conceptual location of the extracted APT sample. b APT reconstruction of the original grain boundary and DIGM zone. c APT line scan 1 as shown in (b) across the original grain boundary. d APT line scan 2 as shown in (b) across the oxide/metal interface in the DIGM zone.

Discussion

The current data show that the initial corrosion response of Ni-30Cr after 1000 h in 360 °C hydrogenated water is consistent with that of solution annealed Alloy 690 under similar conditions34,62,63. TEM and APT data presented in Figs. 1, 2b, c show that the surface of Ni-30Cr formed a nanoscale Cr2O3 protective layer above the grain boundary regions accompanied by the extensive Cr depletion from the underlying alloy grain boundary. This thin film of Cr2O3 effectively inhibited further oxidation of the grain boundary region. Further from the grain boundary intersection with the surface (> 2–3 µm), transgranular oxidation was observed, as demonstrated in Fig. 2d. This is also consistent with the behavior of Alloy 69063, where the density of the oxide penetrations in Alloy 690 was correlated to the dislocation density of the material. The concentration profile of the surface oxide in Fig. 2g shows ~50 at.% O and ~50 at.% metal. This could be consistent with the MO-structure oxide observed by Olszta et al.63, but APT alone cannot assign the specific oxide phase and spinel (M3O4) may also present with a similar O concentration in APT64.

Together these observations of initial surface corrosion demonstrate that although high-Cr Ni-base alloys are highly resistant to IGSCC, they do not form continuous passivating films across their entire surface. Only in the vicinity of the grain boundary where Cr is readily available by means of grain boundary diffusion and DIGM are passivating Cr2O3 oxide films formed. Elsewhere (e.g., grain centers) selective corrosion occurs along dislocations and terminates at a shallow depth (100 s of nm).

By selectively removing the passivating surface oxide films from the surface of Ni-30Cr and reexposing the Cr-depleted regions, the current work has revealed that the Cr-depleted DIGM zone and its associated grain boundary are susceptible to localized, penetrative corrosion. Although a high Cr concentration is still present in the surrounding matrix, the sample grain boundary failed to repassivate. The main supply of Cr to the passivating surface oxide in the initial exposure is through grain boundary diffusion and DIGM. The inability of the grain boundary to repassivate, despite abundant Cr in the adjacent unaltered matrix, suggests that continued DIGM and rapid grain boundary Cr diffusion from deep within the material are inhibited relative to the initial exposure. This may be a result of the longer diffusion distance for Cr along the grain boundary from deep within the material, and/or pinning of the migrated grain boundary. At the same time the migration has left behind a network of dislocations that are intersecting the freshly exposed surface. The SEM images in Fig. 3 show that corrosion through the Cr-depleted area is dominated by the oxidation of these dislocations. Figure 4 shows that oxidation along the grain boundary, adjacent to the undepleted Ni-30Cr matrix, forms Cr2O3. The APT data in Fig. 5 confirms a Cr-rich oxide composition containing ~5 at.% Fe and ~5 at.% Ni in one of the oxides protruding into the DIGM zone. In all cross-sectional images of grain boundaries that had surface oxides removed before re-exposure, the intergranular attack was confined to the Cr-depleted DIGM “pocket” closest to the surface. That is, penetrative corrosion did not breach a cross-over point where the DIGM migration switches to the opposite metal grain. We can speculate from this that the new intergranular oxide acts as a protective oxide, stalling deeper intergranular attack.

SCC initiation in Alloy 690 has been consistently observed in constant extension rate tensile (CERT) tests56,65,66 and in more limited instances (e.g., severely cold-worked Alloy 690) under constant load tensile tests27,31,32,33. It has been hypothesized that a cycle of oxide film rupture and repair during dynamic straining depletes the grain boundary sufficiently to prevent the formation of a new passivating oxide56. The CERT test method exposes the specimens to significant applied strains to cause mechanical fracture of brittle oxide films; these applied strains are much higher than necessary to facilitate crack growth in an already initiated sample. In the current work we extend this understanding in the absence of applied strain to show directly that the Cr-depleted grain boundary region cannot easily repassivate once the protective oxide is removed. Thus dynamic deformation of a CERT test is not a necessary requirement for penetrative intergranular oxidation and potentially embrittlement in these high-Cr alloys37,65,66. However, the partially protective nature of the newly formed intergranular oxide is distinct from the observations in the CERT tests, where dynamic straining led to repeated rupture of passivating oxides and the grain boundary eventually becomes embrittled deeply enough for crack initiation to occur66.

Given the limited depth and diminishing intergranular nature of corrosion, it appears unlikely that the corrosion observed after removal of the surface oxide on Ni-30Cr in the absence of dynamic strain will lead directly to sufficient grain boundary embrittlement for IGSCC initiation. Removal of the surface oxide exposed a small region of metal similar in composition to Ni-5Cr or Alloy 600, and this region was clearly susceptible to corrosion. However, unlike the lower Cr alloys, both the original and the migrated boundary of the Ni-30Cr have Cr-rich metal to one side. Lower Cr alloys, such as Ni-5Cr or Alloy 600, exhibit narrower but much deeper intergranular attack at under similar corrosion conditions and times. For example, Schreiber et al. observed 10 s of micrometers of intergranular attack in a Ni-5Cr alloy exposed to 360 °C hydrogenated water for 1000 h49. In contrast, the depth of the oxide at the re-exposed grain boundary is on the order of 500 nm after 1000 h. With abundant Cr immediately adjacent to the grain boundary in Ni-30Cr, oxygen diffusion along the oxidized grain boundary to sustain deeper intergranular attack is clearly inhibited by the local intergranular Cr2O3 formation which acts to at least partially protect the grain boundary plane from further rapid attack. On the other hand, corrosion in the DIGM zone is dominated by the oxidation of dislocations and resembles observations of the bulk surface of Alloy 600 in 480 °C steam3,54, which are not typically observed at the lower pressurized water exposure temperatures. This suggests a greater driving force for O diffusion in the DIGM zone than in bulk Alloy 600, but much lower driving force than in Alloy 600 grain boundaries where intergranular attack reaches much greater depth in both water and steam3,5,8,46,54,67.

In summary, our findings show that the removal of surface oxide above Cr-depleted grain boundaries of high-Cr Ni-base alloys can lead to penetrative oxidation around degraded grain boundaries. However, given the limited depth of intergranular oxide penetration, it is doubtful that this corrosion will lead directly to significant embrittlement to facilitate sustained crack growth and IGSCC. Even after the removal of the passivating oxide, intergranular attack is much more limited than in low-Cr Ni-base alloys in comparable exposure conditions. However, repeated break down of passivating oxides and injection of progressively deeper cracks into the uncorroded material as generated in dynamic straining experiments can overcome the excellent IGSCC resistance of high-Cr Ni-base alloys.

Methods

Materials

A high-purity Ni-30Cr model alloy, whose nominal composition is reported in Table 1, was used for these studies. Trace impurity concentrations are noted for Fe, Si, B, and S, as determined by glow discharge mass spectrometry (GDMS). The alloy was solution annealed at 900 °C for 1 h and water quenched. It should be noted that APT struggles to differentiate Si, Fe, and N in trace quantities due to isobaric overlaps (28Si2+ with 14N1+, 28Si1+ with 56Fe2+) as there are insufficient counts to use isotopic ratios to deconvolute these overlaps.

Corrosion testing

The polished coupon was exposed to high-temperature (360 °C), hydrogenated water simulating a PWR primary water environment (25 cc/kg dissolved hydrogen, 2 ppm Li, 1000 ppm B) in a stainless steel recirculating autoclave with active deionizer. After initial exposure for 1000 h, the coupon was extracted from the autoclave, sputter-coated with ~50 nm of Ni to protect the thin surface oxide, and mounted into an epoxy mount and polished in cross-section for initial SEM analysis. The coupon was subsequently extracted from the epoxy to enable sectioning for TEM and APT characterization. The removal from the epoxy detached most of the surface spinels. The protective oxide layer over about a dozen individual grain boundaries was then removed via FIB milling, as described below. After FIB sputtering of the protective oxide layer near grain boundaries, the coupon was returned to the autoclave for an additional 1000 h exposure under the same simulated PWR primary water conditions at 360 °C.

Surface oxide removal

The protective surface oxide was locally removed above many grain boundaries using a FIB. This process is demonstrated by SEM images and schematics in Fig. 6. After identifying a target grain boundary, a protective layer of C+Pt (~100–300 nm thick) was deposited in situ by e-beam assisted deposition. This layer both protects the underlying material from Ga ion beam damage and facilitates smoother milling of the metal. Next, a trench, perpendicular to the surface and parallel with the grain boundary, was FIB milled to inhibit local redeposition. The sample was then tilted such that the FIB was at a glancing angle relative to the surface ( ~ 11 deg) and the Pt cap and thin passive oxide were locally removed, while the Cr-depleted grain boundary below was preserved. The surface received a final cleanup with 2 kV Ga at a slightly higher angle ( ~ 13 deg) to further reduce ion beam damage. The coupon was then returned to the autoclave for the final 1000 h re-exposure of the freshly exposed Cr-depleted grain boundaries.

Characterization

Analytical electron microscopy and APT were both performed to characterize the corrosion products and altered grain boundary compositions. Analytical STEM analysis was carried out in a JEOL ARM 200 F equipped with a HAADF detector and a Centurio EDS detector. EDS data were processed using Pathfinder 1.4. APT analyses were performed on a CAMECA LEAP 4000X HR in laser pulsing mode (λ = 355 nm) at a base temperature of 40 K and a laser pulse energy of 30–100 pJ. APT data were reconstructed and analysed using the Integrated Visualization and Analysis Software (IVAS) software package from CAMECA, version 3.8.10. Representative APT mass spectra and ranging can be found in Supplementary Figs. 3, 4. Isoconcentration surfaces were generated in the respective reconstrcutions on a grid with a 1 × 1 × 1 nm3 voxel size and delocalization of 3 × 3 × 1.5 nm3. Samples for STEM and APT analyses were produced by conventional FIB methods, which are further described elsewhere67,68. All samples received a final low kV cleanup (2 kV Ga+) to minimize ion beam damage.

Data availability

The data supporting the presented findings are available in69.

References

Cook, W. G. & Olive, R. P. Pourbaix diagrams for the nickel-water system extended to high-subcritical and low-supercritical conditions. Corros. Sci. 58, 284–290 (2012).

Lim, Y. S., Kim, S. W., Hwang, S. S., Kim, H. P. & Jang, C. Intergranular oxidation of Ni-based alloy 600 in a simulated PWR primary water environment. Corros. Sci. 108, 125–133 (2016).

Bertali, G., Scenini, F. & Burke, M. G. Advanced microstructural characterization of the intergranular oxidation of Alloy 600. Corros. Sci. 100, 474–483 (2015).

Persaud, S. Y., Ramamurthy, S. & Newman, R. C. Internal oxidation of Alloy 690 in hydrogenated steam. Corros. Sci. 90, 606–613 (2015).

Langelier, B., Persaud, S. Y., Newman, R. C. & Botton, G. A. An atom probe tomography study of internal oxidation processes in Alloy 600. Acta Mater. 109, 55–68 (2016).

Kuang, W., Song, M., Wang, P. & Was, G. S. The oxidation of Alloy 690 in simulated pressurized water reactor primary water. Corros. Sci. 126, 227–237 (2017).

Kruska, K., Schreiber, D. K., Olszta, M. J., Riley, B. J. & Bruemmer, S. M. Temperature-dependent selective oxidation processes for Ni-5Cr and Ni-4Al. Corros. Sci. 139, 309–318 (2018).

Fournier, L. et al. Grain Boundary Oxidation and Embrittlement Prior to Crack Initiation in Alloy 600 in PWR Primary Water, Proc. of the 15th International Conference on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power Systems — Water Reactors, 1491-1501 (2016).

Harrison, L. G. Influence of dislocations on diffusion kinetics in solids with particular reference to the alkali halides. Trans. Faraday Soc. 57, 1191–1199 (1961).

Balluffi, R. W. Grain boundary diffusion mechanisms in metals. Metall. Trans. B 13, 527–553 (1982).

Scott, P. & Le Calver, M. Some Possible Mechanisms of Intergranular Stress Corrosion Cracking of Alloy 600 in PWR Primary Water, Proc. of the sixth international symposium on environmental degradation of materials in nuclear power systems-water reactors, (1993).

Scott, P. An Overview of Internal Oxidation as a Possible Explanation of Intergranular Stress Corrosion Cracking of Alloy 600 in PWRs, Proc. of the 9th International Symposium on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power Systems-Water Reactors, 3–14 (1999).

Scott, P. M. & Le, C. M. Some Possible Mechanisms of Intergranular Stress Corrosion Cracking of Alloy 600 in PWR Primary Water, in 6th International Symposium on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power Systems - Water Reactors, E. P. Simonen and R. E. Gold, Editors. 1993, The Minerals, Metals and Materials Society. 657–667.

Thomas, L. E. & Bruemmer, S. M. High-resolution characterization of intergranular attack and stress corrosion cracking of Alloy 600 in high-temperature primary water. Corrosion 56, 572–587 (2000).

Staehle, R. & Fang, Z. Comments on a Proposed Mechanism of Internal Oxidation for Alloy 600 as Applied to Low Potential Scc, Proc. of the Ninth International Symposium on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power Systems-Water Reactors-, 69–78 (1999).

Scott, P. M. & Combrade, P. General corrosion and stress corrosion cracking of Alloy 600 in light water reactor primary coolants. J. Nucl. Mater. 524, 340–375 (2019).

Féron, D. & Staehle R. W. Stress Corrosion Cracking of Nickel Based Alloys in Water-Cooled Nuclear Reactors: The Coriou Effect. 67: Woodhead Publishing (2016).

Lozano-Perez, S., Meisnar, M., Dohr, J. & Kruska, K. Reviewing the Internal Oxidation Mechanism as a Plausible Explanation for Scc in PWR Primary Water. Proc. 16th Int. Conf. on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power Systems–Water Reactors, (2013).

Arioka, K., Yamada, T., Miyamoto, T. & Aoki, M. Intergranular stress corrosion cracking growth behavior of Ni-Cr-Fe alloys in pressurized water reactor primary water. Corrosion 70, 695–707 (2014).

Arioka, K., Yamada, T., Miyamoto, T. & Terachi, T. Scc Initiation of CW Alloy TT690 and Alloy 600 in PWR Water, Proc. 17th International Conference on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power Systems–Water Reactors (Toronto, Canada: CNS, 2015, 2015).

Karwoski, K., Maker, G. & Yoder, M. Us operating experience with thermally treated alloy 690 steam generator tubes, NRC Report Number: NUREG-1841, United States (2007).

Chen, K. et al. Effect of intergranular carbides on the cracking behavior of cold worked Alloy 690 in subcritical and supercritical water. Corros. Sci. 164, 108313 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. Characterizing the effect of creep on stress corrosion cracking of cold worked Alloy 690 in supercritical water environment. J. Nucl. Mater. 492, 32–40 (2017).

Chen, K. et al. Comparison of the stress corrosion cracking growth behavior of cold worked Alloy 690 in subcritical and supercritical water. J. Nucl. Mater. 520, 235–244 (2019).

Lim, Y. S., Kim, D. J., Kim, S. W. & Kim, H. P. Crack growth and cracking behavior of Alloy 600/182 and Alloy 690/152 welds in simulated PWR primary water. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 51, 228–237 (2019).

Chen, K. et al. Effect of cold work on the stress corrosion cracking behavior of Alloy 690 in supercritical water environment. J. Nucl. Mater. 498, 117–128 (2018).

Zhai, Z., Toloczko, M., Kruska, K. & Bruemmer, S. Precursor evolution and stress corrosion cracking initiation of cold-worked Alloy 690 in simulated pressurized water reactor primary water. Corrosion 73, 1224–1236 (2017).

Toloczko, M. B., Olszta, M. J. & Bruemmer, S. M. One Dimensional Cold Rolling Effects on Stress Corrosion Crack Growth in Alloy 690 Tubing and Plate Materials, Proc. of the 15th International Conference on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power Systems—Water Reactors, 91-107 (2011).

Bruemmer, S., Olszta, M., Overman, N. & Toloczko, M. Cold Work Effects on Stress Corrosion Crack Growth in Alloy 690 Tubing and Plate Materials. 17th International Conference on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power Systems—Water Reactors, Paper No. 199 (2015).

Arioka, K., Yamada, T., Miyamoto, T. & Terachi, T. Dependence of stress corrosion cracking of Alloy 690 on temperature, cold work, and carbide precipitation—role of diffusion of vacancies at crack tips, Corrosion 67, 035006-1–035006-18 (2011).

Zhai, Z., Olszta, M., Toloczko, M. & Bruemmer, S. Crack initiation behavior of cold-worked alloy 690 in simulated Pwr primary water—role of starting microstructure, applied stress and cold work on precursor damage evolution, Proc. of the 19th International Conference on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power Systems - Water Reactors, Paper No. 28043 (2019).

Zhai, Z., Toloczko, M. & Bruemmer, S. Long-Term Crack Initiation Behavior of Cold-Worked Alloy 690 in PWR Primary Water, CORROSION 2021, (2021).

Zhai, Z., Olszta, M. J. & Toloczko, M. B. Long-Term Aging Behavior of Cold-Worked Alloy 690 in Simulated Pwr Primary Water, in 20th International Conference on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power Systems - Water Reactors. (2022).

Olszta, M., Schreiber, D., Toloczko, M. & Bruemmer, S. Alloy 690 Surface Nanostructures During Exposure to Pwr Primary Water and Potential Influence on Stress Corrosion Crack Initiation, Proc. of the 16th international symposium on environmental degradation of materials in nuclear power system—water reactors, minerals, metals and materials society/AIME, (2013).

Carrette, F., Lafont, M. C., Legras, L., Guinard, L. & Pieraggi, B. Analysis and TEM examinations of corrosion scales grown on Alloy 690 exposed to PWR environment. Mater. High. Temp. 20, 581–591 (2003).

Huang, F., Wang, J., Han, E.-H. & Ke, W. Microstructural characteristics of the oxide films formed on Alloy 690 TT in pure and primary water at 325°C. Corros. Sci. 76, 52–59 (2013).

Moss, T., Cao, G. & Was, G. S. Oxidation of Alloy 600 and Alloy 690: Experimentally accelerated study in hydrogenated supercritical water. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 48, 1596–1612 (2017).

Kuang, W. & Was, G. S. The effect of grain boundary structure on the intergranular degradation behavior of solution annealed Alloy 690 in high temperature, hydrogenated water. Acta Mater. 182, 120–130 (2020).

Shen, Z. et al. On the role of intergranular nanocavities in long-term stress corrosion cracking of Alloy 690. Acta Mater. 222, 117453 (2022).

Brimbal, D. et al. Long range ordering in thermally treated and cold-worked Alloy 690, in 20th International Conference on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power Systems - Water Reactors. (2022).

Yonezawa, T. & Hashimoto, A. Evaluating the reliability of PWSCC resistance of TT Alloy 690 and associated welds to the end of anticipated PWR Plant Life. J. Nucl. Mater. 560, 153461 (2022).

Yonezawa, T. & Hashimoto, A. Effect of cold working and long-term heating in air on the stress corrosion cracking growth rate in commercial TT Alloy 690 exposed to simulated PWR primary water. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 52, 3274–3288 (2021).

Mouginot, R. et al. Thermal ageing and short-range ordering of Alloy 690 between 350 and 550 °C. J. Nucl. Mater. 485, 56–66 (2017).

Moss T. E., Brown C. M. & Young G. A. The effect of hardening via long range order on the SCC and LTCP susceptibility of a nickel-30chromium binary alloy, Proc. of the 18th International Conference on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power Systems–Water Reactors, 261–279 (2019).

Volpe, L., Burke, M. G. & Scenini, F. Correlation between grain boundary migration and stress corrosion cracking of Alloy 600 in hydrogenated steam. Acta Mater. 186, 454–466 (2020).

Persaud, S. Y. et al. Characterization of initial intergranular oxidation processes in Alloy 600 at a sub-nanometer scale. Corros. Sci. 133, 36–47 (2018).

Xue, F. & Marquis, E. A. Role of diffusion-induced grain boundary migration in the oxidation response of a Ni-30 Cr alloy. Acta Mater. 240, 118343 (2022).

Schreiber, D. K., Olszta, M. J. & Bruemmer, S. M. Directly correlated transmission electron microscopy and atom probe tomography of grain boundary oxidation in a Ni–Al binary alloy exposed to high-temperature water. Scr. Mater. 69, 509–512 (2013).

Schreiber, D. K., Olszta, M. J. & Bruemmer, S. M. Grain boundary depletion and migration during selective oxidation of Cr in a Ni–5Cr binary alloy exposed to high-temperature hydrogenated water. Scr. Mater. 89, 41–44 (2014).

Volpe, L., Burke, M. G. & Scenini, F. Understanding the role of diffusion induced grain boundary migration on the preferential intergranular oxidation behaviour of Alloy 600 via advanced microstructural characterization. Acta Mater. 175, 238–249 (2019).

Tedmon, C. S. Jr & Vermilyea, D. A. Carbide sensitization and intergranular corrosion of nickel base alloys. Corrosion 27, 376–381 (1971).

Cahn, J. W., Pan, J. D. & Balluffi, R. W. Diffusion induced grain boundary migration. Report Number: COO-5002-2, United States. https://doi.org/10.2172/6146335 (1979).

Bruemmer, S. M., Olszta, M. J., Toloczko, M. B. & Schreiber, D. K. Grain boundary selective oxidation and intergranular stress corrosion crack growth of high-purity nickel binary alloys in high-temperature hydrogenated water. Corros. Sci. 131, 310–323 (2018).

Langelier, B. et al. Effects of boundary migration and pinning particles on intergranular oxidation revealed by 2d and 3d analytical electron microscopy. Acta Mater. 131, 280–295 (2017).

Bertali, G., Burke, M. G., Scenini, F. & Huin, N. The effect of temperature on the preferential intergranular oxidation susceptibility of Alloy 600. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 49, 1879–1894 (2018).

Moss, T., Kuang, W. & Was, G. S. Stress corrosion crack initiation in Alloy 690 in high temperature water. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 22, 16–25 (2018).

Hatzoglou, C., Radiguet, B., Vurpillot, F. & Pareige, P. A chemical composition correction model for nanoclusters observed by APT-application to ODS steel nanoparticles. J. Nucl. Mater. 505, 240–248 (2018).

Kruska, K. & Schreiber, D. K. Background recovery through the quantification of delayed evaporation multi-ion events in atom-probe data. Microsc. Microanal. 21, 857–858 (2015).

Schreiber, D. K., Chiaramonti, A. N., Gordon, L. M. & Kruska, K. Applicability of post-ionization theory to laser-assisted field evaporation of magnetite. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 244106 (2014).

Bachhav, M., Danoix, F., Hannoyer, B., Bassat, J. M. & Danoix, R. Investigation of O-18 enriched hematite (Α-Fe2O3) by laser assisted atom probe tomography. Int. J. Mass spectrom. 335, 57–60 (2013).

Yu, X. et al. Nonequilibrium solute capture in passivating oxide films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 145701 (2018).

Lim, Y. S., Kim, D. J., Kim, S. W., Hwang, S. S. & Kim, H. P. Characterization of internal and intergranular oxidation in Alloy 690 exposed to simulated PWR primary water and its implications with regard to stress corrosion cracking. Mater. Charact. 157, 109922 (2019).

Olszta M. J., Schreiber D. K., Thomas L. E. & Bruemmer S. M. Penetrative Internal Oxidation from Alloy 690 Surfaces and Stress Corrosion Crack Walls During Exposure to Pwr Primary Water, in Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power Systems - Water Reactors, J. T. Busby, G. Ilevbare, and P. L. Andresen, Editors. 2011, The Minerals, Metals and Materials Society: Colorado Springs, CO. 331-342.

Yano, K. H. et al. Radiation-enhanced anion transport in hematite. Chem. Mater. 33, 2307–2318 (2021).

Kuang, W., Song, M. & Was, G. S. Insights into the stress corrosion cracking of solution annealed Alloy 690 in simulated pressurized water reactor primary water under dynamic straining. Acta Mater. 151, 321–333 (2018).

Moss, T. & Was, G. S. Accelerated stress corrosion crack initiation of Alloys 600 and 690 in hydrogenated supercritical water. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 48, 1613–1628 (2017).

Langford, R. M. & Rogers, M. In situ lift-out: Steps to improve yield and a comparison with other FIB TEM sample preparation techniques. Micron 39, 1325–1330 (2008).

Thompson, K. et al. In situ site-specific specimen preparation for atom probe tomography. Ultramicroscopy 107, 131–139 (2007).

Kruska, K., Olszta, M. J., Wang, J. & Schreiber, D. K. Microscopy and spectroscopy of Ni-30cr before and after removal of passivating film, Mendeley Data, V1, https://doi.org/10.17632/mt2rpk4xyn.1 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division, Mechanical Behavior and Radiation Effects (FWP 56909). Atom probe tomography measurements were performed on a project award (10.46936/cpcy.proj.2020.51701/60000260) from the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory, a DOE Office of Science User Facility sponsored by the Biological and Environmental Research at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL). PNNL is a multiprogram national laboratory operated by Battelle for the U.S. DOE under Contract DE-AC05-79RL01830.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Karen Kruska and Matthew J. Olszta contributed equally to this work. Karen Kruska: investigation, methodology, formal analysis, visualization, writing - original draft. Matthew J Olszta: investigation, formal analysis, visualization, writing – editing and review. Jing Wang: investigation, writing – editing and review. Daniel K Schreiber: conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, supervision, writing – editing and review, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kruska, K., Olszta, M.J., Wang, J. et al. Intergranular corrosion of Ni-30Cr in high-temperature hydrogenated water after removing surface passivating film. npj Mater Degrad 8, 25 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-024-00442-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-024-00442-0